To report the clinical characteristics of patients with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), and to ascertain their metabolic control and associated chronic complications.

MethodsPatients with DM attending specialized medical care in Madrid who met the following criteria: age at diagnosis of DM >30years, initial insulin independence for at least 6months and positive GAD antibodies were enrolled. Clinical profiles, data on LADA diagnosis, associated autoimmunity, C-peptide levels, therapeutic regimen, metabolic control, and presence of chronic complications were analyzed.

ResultsNumber of patients; 193; 56% females. Family history of DM: 62%. Age at DM diagnosis: 49years. Delay in confirmation of LADA: 3.5years. Insulin-independence time: 12months. Baseline serum C-peptide levels: 0.66ng/ml. Basal-bolus regimen: 76.7%. Total daily dose: 35.1U/day, corresponding to 0.51U/kg. With no associated oral antidiabetic drugs: 33.5%. Other autoimmune diseases: 57%. Fasting plasma glucose: 160.5mg/dL. HbA1c: 7.7%. BMI: 25.4kg/m2 (overweight, 31.5%; obesity, 8%). Blood pressure: 128/75. HDL cholesterol: 65mg/dL. LDL cholesterol: 96mg/dL. Triglycerides: 89mg/dL. Known chronic complications: 28%.

ConclusionsRecognition of LADA may be delayed by several years. There is a heterogeneous pancreatic insulin reserve which is negative related to glycemic parameters. Most patients are poorly controlled despite intensive insulin therapy. They often have overweight, but have adequate control of BP and lipid profile and a low incidence of macrovascular complications.

Definir las características clínicas de los pacientes con diabetes autoinmune latente del adulto (LADA), conocer su control metabólico y las complicaciones crónicas asociadas que presentan.

MétodosSeleccionamos pacientes con DM seguidos en las consultas de endocrinología de hospitales públicos de la Comunidad de Madrid que reunían los siguientes criterios: edad al diagnóstico de DM >30años, independencia inicial de insulina durante al menos 6meses y positividad de anticuerpos antiGAD. Analizamos datos clínicos relativos al diagnóstico de LADA, autoinmunidad asociada, niveles de péptido C, pauta terapéutica, control metabólico y presencia de complicaciones crónicas.

ResultadosNúmero de pacientes: 193. Mujeres: 56%. Antecedentes familiares de DM: 62%. Edad al diagnóstico de DM: 49años. Retraso en confirmación LADA: 3,5años. Tiempo de insulino-independencia: 12meses. Péptido C basal suero: 0,66ng/ml (0,22nmol/l). Pauta de insulina basal-bolus: 76,7%. Dosis total diaria: 35,1U/día, correspondiente a 0,51U/kg. Sin fármacos orales asociados: 33,5%. Presencia de otras patologías autoinmunes: 57%. Glucemia en ayunas: 160,5mg/dl (8,91mmol/l). HbA1c: 7,7%. IMC: 25,4kg/m2 (sobrepeso: 31,5%; obesidad: 8%). Presión arterial: 128/75. Colesterol HDL: 65mg/dl (16,9mmol/l). Colesterol LDL: 96mg/dl (24,96mmol/l). Triglicéridos: 89mg/dl (1,01mmol/l). Complicaciones crónicas: 28%; microangiopatía: 23,1%; macroangiopatía: 4,9%.

ConclusionesEl reconocimiento de LADA puede retrasarse varios años. La reserva pancreática de insulina de los pacientes es heterogénea y el grado medio de control glucémico deficiente a pesar de utilizar mayoritariamente insulinoterapia intensiva. Con frecuencia presentan sobrepeso, aunque tienen un control adecuado de la presión arterial y perfil lipídico y baja incidencia de complicaciones macroangiopáticas.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a pathophysiologically complex and heterogeneous disease that often goes beyond the somewhat rigid limits of the categories considered in the current classification.1

The so-called latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult (LADA) is a slowly progressing autoimmune diabetes which is often not recognized as such and is confused with other types of DM. Positive islet cell antibodies (ICAs) have however been found in more than 10% of adults with type 2 DM (T2DM).2,3 LADA therefore represents the most prevalent form of autoimmune diabetes in adults, and is also probably the most prevalent form of autoimmune diabetes overall.4

Although LADA is undoubtedly related to type 1 DM (T1DM), its clinical presentation often includes features attributable to T2DM, which often leads to a wrong diagnosis and treatment for significant periods of time. The fact that the diagnostic criteria currently used to identify this variant of diabetes are imprecise and controversial contributes to this.

The purpose of this study was to help in clinical characterization of patients with LADA using specialized medical monitoring, and to study their metabolic control and the occurrence of chronic complications related to DM.

MethodsA retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted on patients with DM attending endocrinology departments of the public healthcare network of the region of Madrid. Cases were detected based on a systematic search in our clinic appointment books and databases (which did not necessarily include all cases at each hospital) for patients with the criteria listed below. The selection process lasted from May 2015 to February 2016, and the database was completed by collecting the information available at the hospital records.

Patients enrolled met all three criteria of LADA proposed by the Immunology of Diabetes Society (IDS)5: diagnosis of diabetes based on the established criteria at ages older than 30years, insulin independence for at least six months after diagnosis, and positive glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies (GADA). Patients with secondary and gestational diabetes and diabetes associated to malignancies were excluded.

Data collected included age, sex, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), family history of diabetes, date of clinical diagnosis of diabetes and confirmation of LADA, GADA titer, associated autoimmune diseases or presence of organ-specific antibodies, basal plasma C-peptide levels, insulin regimen and dosage, other associated antidiabetic and cardiovascular drugs, metabolic glucose, lipid, and blood pressure control, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, and presence of microangiopathic and macroangiopathic complications. Biochemical and immunological data were assessed at the reference laboratories of the respective hospitals.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software. Normally distributed data are given as mean (standard deviation). Non-normally distributed data are given as median (range). GADA titer is given as the ratio between the resulting absolute value and the upper limit of normal for each laboratory. Association or interdependence of two variables was calculated using Spearman's correlation coefficient.

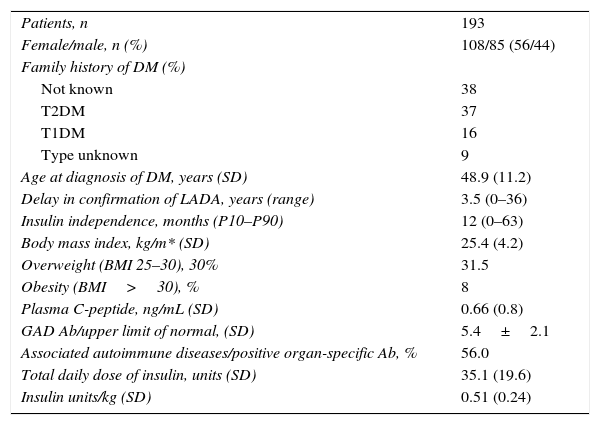

ResultsTable 1 shows the demographic characteristics of our patients and information on their diabetes. Data were collected from 193 patients, of whom 108 (56%) were women. Thirty-eight percent of patients had no known family history of diabetes, 37% and 16% had a family history of T2DM and T1DM respectively, and 8.7% had a history of DM of an unknown type.

Clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Patients, n | 193 |

| Female/male, n (%) | 108/85 (56/44) |

| Family history of DM (%) | |

| Not known | 38 |

| T2DM | 37 |

| T1DM | 16 |

| Type unknown | 9 |

| Age at diagnosis of DM, years (SD) | 48.9 (11.2) |

| Delay in confirmation of LADA, years (range) | 3.5 (0–36) |

| Insulin independence, months (P10–P90) | 12 (0–63) |

| Body mass index, kg/m* (SD) | 25.4 (4.2) |

| Overweight (BMI 25–30), 30% | 31.5 |

| Obesity (BMI>30), % | 8 |

| Plasma C-peptide, ng/mL (SD) | 0.66 (0.8) |

| GAD Ab/upper limit of normal, (SD) | 5.4±2.1 |

| Associated autoimmune diseases/positive organ-specific Ab, % | 56.0 |

| Total daily dose of insulin, units (SD) | 35.1 (19.6) |

| Insulin units/kg (SD) | 0.51 (0.24) |

Mean age at diagnosis of DM was 48.9±11.2 years. Diagnosis of LADA, defined as the date when positive GADA were found, was made with a delay of 3.5years (range, 0–36) after clinical diagnosis of DM.

GADA titer, expressed as the GADA/upper limit of normal ratio, was 5.4±2.1U/L. No correlation was seen between GADA titer, C-peptide levels, and insulin independence time.

Patients were treated with diet and oral antidiabetic drugs only for a median of 12months (P10: 1; P90: 63).

BMI was 25.4±4.2kg/m2. Overweight (BMI: 25–29.9) was found in 31.5% of patients, while 8% of patients were obese (BMI>30). No correlation was found between BMI and blood glucose control.

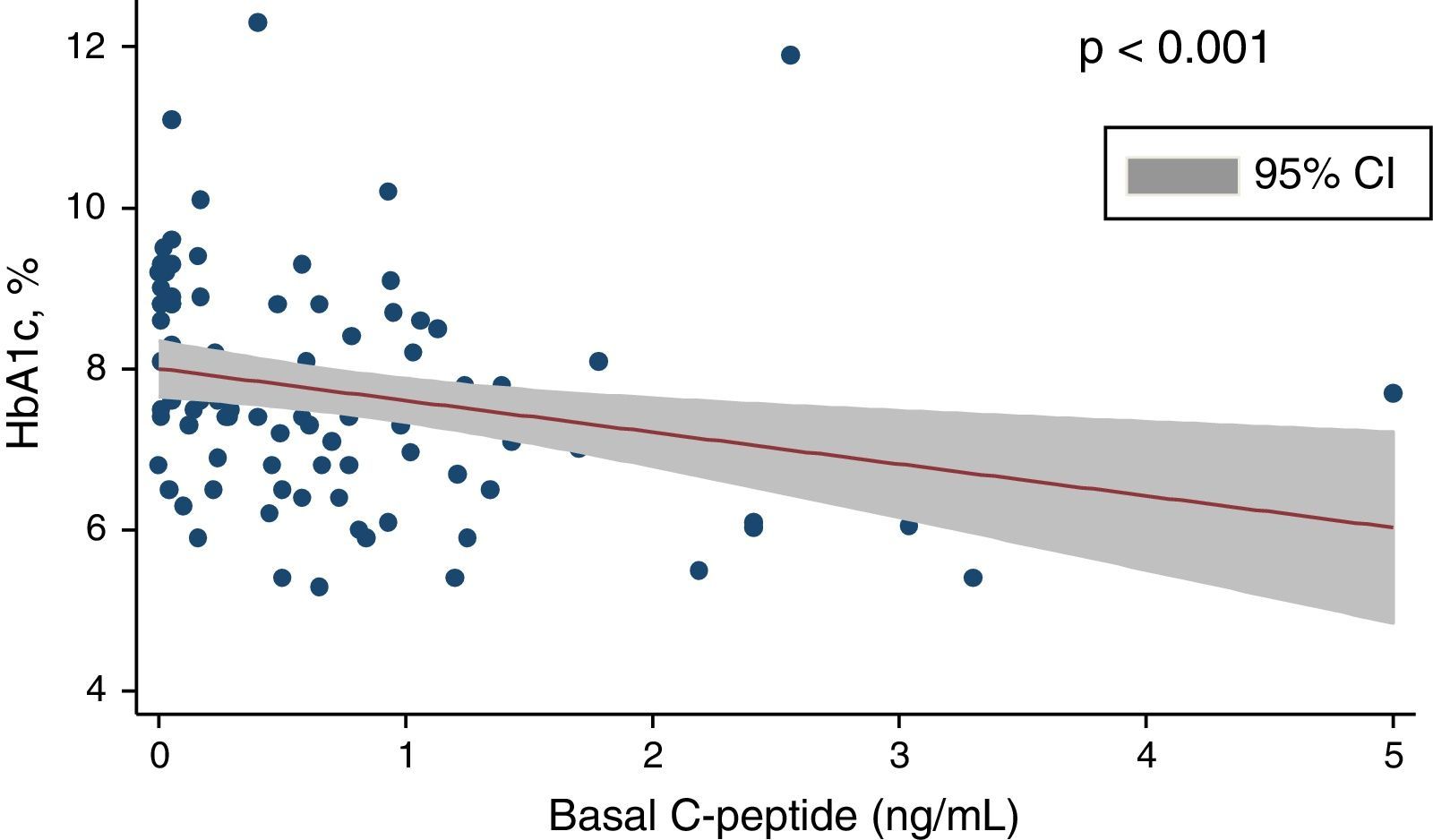

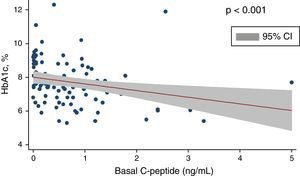

Basal plasma C-peptide levels of patients were measured at different times after DM onset. Mean levels were 0.66±0.8ng/mL, but a significant heterogeneity was seen in the values found, which were clearly related to the time since onset of DM, showing a significant negative correlation (Spearman's rho: −0.52; p<0.0001). Twenty-seven percent of patients had C-peptide levels <0.05ng/mL, 49% had levels ranging from 0.05 and 1.0ng/mL, and 24% had levels >1.0ng/mL. A majority of patients (70%) in this last subgroup had a known diabetes duration shorter than one year at the time of C-peptide measurement.

Basal-bolus insulin regimens were most commonly given to our patients (76.7%), followed by basal insulin (13.2%), premixes (4.2%), basal-plus regimens (2.6%), and CSII (0.5%). Only 2.6% of patients received no insulin therapy.

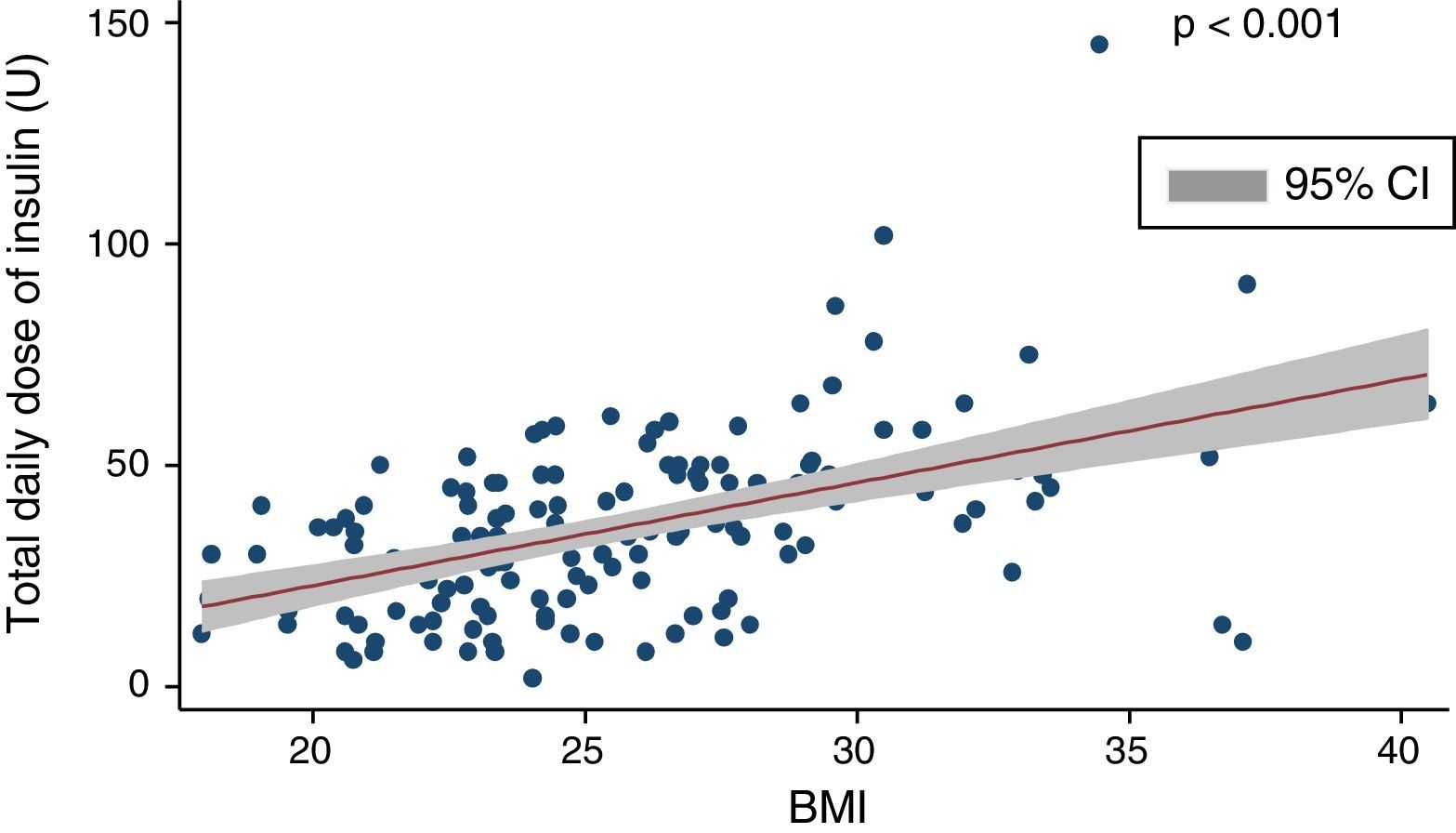

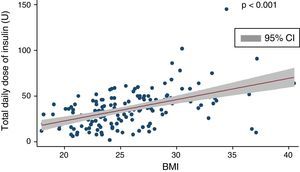

Mean insulin dose was 35.1±19.6U/day, which corresponded to 0.51±0.24U/kg after adjustment for body weight. A positive, significant correlation (coef. 2.32; p<0.001) was found between total insulin dose and BMI (Fig. 1), and there was a negative correlation between total daily insulin dose and C-peptide levels (Spearman's rho: −0.33; p<0.01).

No concomitant non-insulin drugs were received by 66.5% of patients. Metformin was the drug most commonly used (in 25.7% of patients), followed by DPP-4 inhibitors (7.3%), GLP-1 receptor agonists (2.2%), and SGLT2 inhibitors (1.1%). Use of secretagogues and glitazones was very limited (0.6%).

Fifty-seven percent of patients had other autoimmune diseases or positive organ-specific antibodies. Chronic thyroiditis was the most prevalent concomitant condition (occurring in 32.9% of patients). Other autoimmune conditions seen included atrophic gastritis (3.2%), vitiligo (2.4%), Graves’ disease (1.9%), Crohn's disease (1.2%), and celiac disease (1.2%).

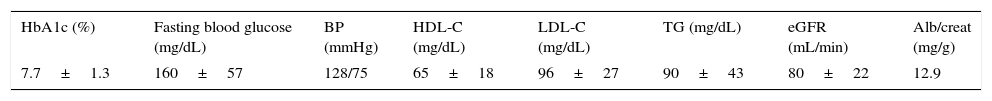

Table 2 provides data on metabolic control of patients. Fasting blood glucose levels were 160.5±57.3mg/dL, and HbA1c values were 7.7±1.26%. Only 31.7% of patients met metabolic control criteria (HbA1c ≤7.0 in two of the last three measurements performed); 31.1% had HbA1c values ranging from 7.1 and 8.0, 23.6% values ranging from 8.1 and 9.0, and 13.4% levels >9%. A significant negative correlation (Spearman's rho: −0.40; p<0.001) was found between HbA1c and C-peptide (Figs. 1 and 2) and between fasting glucose and C-peptide (Spearman's rho: −0.27; p<0.01).

Data on metabolic control of patients.

| HbA1c (%) | Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | BP (mmHg) | HDL-C (mg/dL) | LDL-C (mg/dL) | TG (mg/dL) | eGFR (mL/min) | Alb/creat (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.7±1.3 | 160±57 | 128/75 | 65±18 | 96±27 | 90±43 | 80±22 | 12.9 |

Alb/creat: urinary albumin/creatinine ratio; HDL-C: HDL cholesterol; LDL-C: LDL cholesterol; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; BP: blood pressure; TG: triglycerides.

Lipid control was usually highly satisfactory: HDL cholesterol, 65±18mg/dL; LDL cholesterol, 96±27mg/dL; triglycerides, 89±44mg/dL. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 80±22mL/min, and only 5% of patients had values suggesting kidney failure (eGFR<60mL/min). Mean urinary albumin/creatinine ratio was 12.9mg/g. Criteria for microalbuminuria (ratio, 30–300mg/g) were met by 7.6% of patients, and only 0.6% had macroalbuminuria (ratio >300mg/g). Mean blood pressure values were 128/75mmHg.

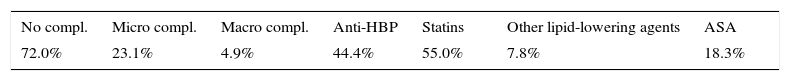

Overall, 44.4% of patients were being treated with antihypertensive drugs, 55% with statins, 7.8% with other lipid-lowering agents, and 18.3% with antiplatelet aggregants.

A majority of patients (72.0%) had no clinical evidence of chronic complications related to diabetes (Table 3). In the remaining 28%, most complications seen (23.1%) were microangiopathic in nature: non-proliferative retinopathy (7.2%), proliferative retinopathy (3.3%), diabetic macular edema (1.6%), incipient nephropathy (6.6%, advanced nephropathy (1.1%), sensory neuropathy (3.3%)). Only 4.9% of patients had been diagnosed some macroangiopathic complication: ischemic heart disease (3.3%), peripheral artery disease (1.6%). No patient experienced stroke.

Chronic complications and cardiovascular drugs.

| No compl. | Micro compl. | Macro compl. | Anti-HBP | Statins | Other lipid-lowering agents | ASA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72.0% | 23.1% | 4.9% | 44.4% | 55.0% | 7.8% | 18.3% |

ASA: acetiy salicylic acid; Anti-HBP: antihypertensives: Compl.: complications; Macro: macroangiopathic; Micro: microangiopathic.

LADA is currently considered as an end of the spectrum of autoimmune diabetes, but does not represent a differentiated group within the general classification of diabetes, but a variant within the T1DM category.

Latent autoimmune diabetes was already described4 in 1986 as a form of DM that occurred in adults with no insulin dependence during an initial period but with early failure of oral antidiabetic treatment, presence of ICA and other frequently associated organ-specific antibodies. Patients reported in the initial report had lower BMIs and less pancreatic reserve of C-peptide as compared to ICA-negative diabetic patients.

The term LADA was introduced in 19956 to describe a subgroup of patients with the above mentioned clinical characteristics who had positive GADA.

Because of the pathophysiological heterogeneity of diabetes, it is often an oversimplification to try and attribute the category of T1DM or T2DM only to patients who have a genetic predisposition to both types of diabetes or who are subject to the influence of environmental factors that result in development of insulin resistance. In fact, patients with LADA have been shown to share the genetic characteristics of classical T1DM,7,8 but they often also have genetic similarities with T2DM,9 which suggests a mixed nature of this form of diabetes.

In our study population, diagnosis of LADA was based on the finding of positive GADA in patients in whom the condition was clinically suspected (diagnosis at adult age, absence of ketoacidosis and initial insulin independence, glycemic variability with marked postprandial component, etc.). Patient characteristics are therefore not comparable to those in non-selective immune screening studies conducted in patients who phenotypically have T2DM.

In this regard, as previously noted,10 we think that generalized screening for LADA in the adult diabetic population is not effective. However, LADA should be routinely ruled out when an adult with diabetes does not show the usual stereotype of T2DM.

Our patients had as a group lower BMIs than expected for a population with T2DM, but were frequently overweight, which agrees with other reported studies.11 High BMI values should therefore not exclude or delay screening for LADA if they coexist with other suspicious clinical factors.

Various studies have reported lower plasma C-peptide levels in the group of patients with LADA as compared to T2DM.12,13 Our study revealed a significant heterogeneity in pancreatic reserve, which also had a negative correlation to blood glucose control. Thus, if LADA is clinically suspected, presence of detectable C-peptide levels should not rule out the condition until the results of the immune study are available.

No guidelines are currently available for the treatment of LADA, but some studies have shown that early administration of insulin or sensitizing oral drugs may be beneficial for long-term preservation of the pancreatic reserve, while sulfonylureas may decrease the insulin independence time.14–16 Our study found a negative correlation between C-peptide levels and blood glucose control, thus emphasizing the importance of early identification of LADA both to increase insulin independence time and to improve metabolic control of patients.

GADA titer has been reported to be inversely related to the pancreatic reserve, and may be a marker of the risk of progression to insulin dependence.14,17–19 Our study found no association between GADA values, C-peptide levels, or insulin independence time, but it was not a prospective study, and the immune and metabolic study was not performed at the time of clinical onset, but often with a delay of up to several years.

This study has other obvious limitations. It was an observational study based on the information recorded in clinical histories, which is subject to data collection problems or errors. Omission bias, especially in the presence of chronic complications, may be significant and underestimate their prevalence, disregarding subclinical forms. Patient selection was based on the most commonly agreed diagnostic criteria,5 but we are aware of their limitations: the age criterion is arbitrary, insulin independence time is highly physician-dependent, and GADA levels may decrease over time and even become negative in patients with long-standing disease.20 A less rigid selection would have markedly increased the number of patients enrolled, but also the number of false positives. Finally, it should be recognized that as these patients attended specialized care clinics, the study population is not probably a faithful representation of the overall group of patients with LADA.

Despite these limitations, we think that our study may help define patients with LADA in order to identify them as such as early as possible and select the most adequate treatment, thus avoiding years of unawareness by patients, their relatives, and the medical team.

As a conclusion, it should be noted that in the study population, diagnosis of LADA may be delayed up to several years. Patients have a quite heterogeneous pancreatic insulin reserve, which is negatively related to time since onset of disease. Treatment of patients with LADA is often difficult, as shown by the deficient blood glucose control despite high compliance with complete insulinization regimens. A successful control is however seen of other treatment goals such as blood pressure and lipid profile, together with a low incidence of macroangiopathic complications.

Conflict of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

We thank Miguel Sampedro for his help in statistical processing and graph preparation.

Alpañés, Macarena; Andía, Victor, Arranz, Alfonso; Arrieta, Francisco; Brito, Miguel; Calle Alfonso; Canovas, Gloria; del Cañizo, Francisco; Cruces, Eva; Durán, María; García, Elena; Gargallo, Manuel; González, Noemí; González, Olga; Lecumberri, Edurne; Lisbona, Arturo; Maillo, Maria Angeles; Nattero, Lía; Parra, Paola; Sánchez, Iván.

Please cite this article as: Arranz Martín A, Lecumberri Pascual E, Brito Sanfiel MÁ, Andía Melero V, Nattero Chavez L, Sánchez López I, et al. Perfil clínico y metabólico de pacientes con diabetes tipo LADA atendidos en atención especializada en la comunidad de Madrid. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2017;64:34–39.

The names of the components of the Diabetes Group of the Society of Endocrinology, Nutrition and Diabetes of Madrid (SENDIMAD) are listed in Annex.