Gastrointestinal disorders are common in the general population and even more frequent in diabetics.1 More specifically, high volume watery diarrhea may have a complex and multifactorial etiology, run a chronic and relapsing course and be refractory to conventional antidiarrheal treatments.2 There are no specific recommendations for a diagnostic approach. We report a patient with high volume diarrhea, refractory to several empirical therapies. He required hospital admission due to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, during which he underwent diagnostic procedures that allowed for the exclusion of small intestine and pancreatic disease and bacterial overgrowth. The diarrhea was attributed to diabetic enteropathy and there was a favorable response to clonidine.

An 81-year-old male was admitted in an Internal Medicine ward in July 2016 with severe and explosive watery diarrhea of twelve weeks duration associated to hypokalemia and dehydration. Bowel frequency was up to eight times per day and one to three times at night and was associated with flatulence, abdominal cramps, fecal urgency and a 13% weight loss since onset was documented. There was no reference to blood loss, fever, abdominal distension or other complaints. Over the past 3 months he had been admitted on two previous occasions with similar episodes and had been treated unsuccessfully with fasting, hydration, ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, probiotics and loperamide. There was no epidemiologic association and no surgical history.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus had been diagnosed 30 years prior to the current admission with established macro and micro-vascular complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy and diabetic foot and peripheral neuropathy. He also suffered from arterial hypertension, New York Heart Association class II heart failure and anemia of chronic disease. Current medication included lispro-insulin (10U-morning, 8U-night), linagliptin 5mg od, isossorbid-dinitrate 20mg od, lercanidipin 10mg od, furosemide 40mg od, rosuvastatin 10mg od, lansoprazol 30mg od and pregabalin 75mg bd. Potassium-chloride 600mg od had been added from the previous hospital admission.

Physical examination revealed pallor, dehydration, blood pressure 162/97mmHg and heart rate 71 beats/minute. The abdomen was tender but without peritoneal irritation and there was no organomegaly. The rest of the examination was unremarkable.

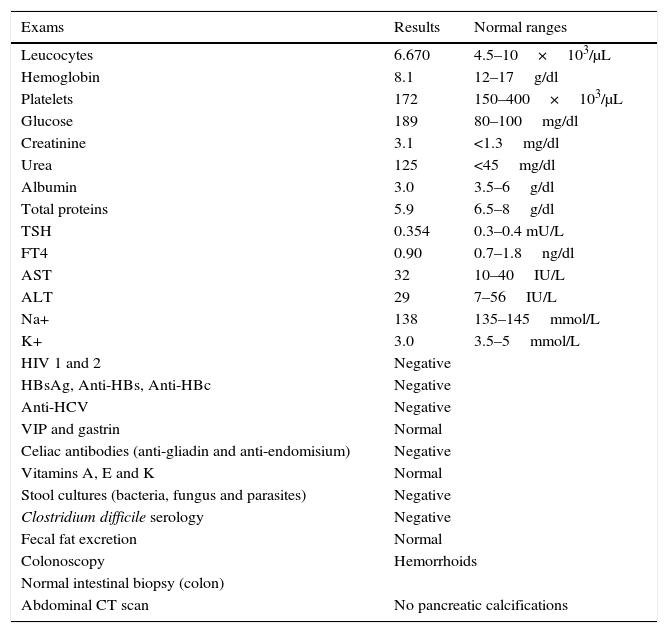

Extensive investigations failed to reach a specific diagnosis (Table 1). The absence of pancreatic calcifications and normal fecal fat excretion excluded chronic pancreatitis.

Exams.

| Exams | Results | Normal ranges |

|---|---|---|

| Leucocytes | 6.670 | 4.5–10×103/μL |

| Hemoglobin | 8.1 | 12–17g/dl |

| Platelets | 172 | 150–400×103/μL |

| Glucose | 189 | 80–100mg/dl |

| Creatinine | 3.1 | <1.3mg/dl |

| Urea | 125 | <45mg/dl |

| Albumin | 3.0 | 3.5–6g/dl |

| Total proteins | 5.9 | 6.5–8g/dl |

| TSH | 0.354 | 0.3–0.4 mU/L |

| FT4 | 0.90 | 0.7–1.8ng/dl |

| AST | 32 | 10–40IU/L |

| ALT | 29 | 7–56IU/L |

| Na+ | 138 | 135–145mmol/L |

| K+ | 3.0 | 3.5–5mmol/L |

| HIV 1 and 2 | Negative | |

| HBsAg, Anti-HBs, Anti-HBc | Negative | |

| Anti-HCV | Negative | |

| VIP and gastrin | Normal | |

| Celiac antibodies (anti-gliadin and anti-endomisium) | Negative | |

| Vitamins A, E and K | Normal | |

| Stool cultures (bacteria, fungus and parasites) | Negative | |

| Clostridium difficile serology | Negative | |

| Fecal fat excretion | Normal | |

| Colonoscopy | Hemorrhoids | |

| Normal intestinal biopsy (colon) | ||

| Abdominal CT scan | No pancreatic calcifications | |

Legend: Anti-HBc, anti-hepatits Bc antibody; Anti-HBs, anti-hepatits Bc antibody; Anti-HCV, anti-hepatitis C antibody; HBsAg, hepatitis Bs antigen; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CT, computurized tomography; FT4, free thyroxine; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; VIP, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide.

We decided to start a trial therapy with clonidine in a maximum dose of 0.3mg td with a good clinical response (decreased stool weight and frequency and more consistency). We progressively reduced its doses to 0.15mg bd with sustained clinical response. Nevertheless some side effects were noted, namely: dry mouth, drowsiness (both disappeared after 48h) and asymptomatic hypotension that was controlled with the reducing doses of clonidine and the anti-hypertensive drugs.

Diabetes affects virtually every organ system in the body and the duration and severity of the disease may have a direct impact on organ involvement.3

Chronic diarrhea in diabetics may be caused by multiple etiologies such as ingestion of artificial sweeteners, celiac disease, bacterial overgrowth, irritable bowel syndrome, or medication side effects, such as metformin or acarbose.1 Other causes also include pancreatic insufficiency, bile salt malabsorption or steatorrhea and it may even be associated with fecal incontinence. As diabetic enteropathy is a diagnosis of exclusion, it is important to exclude all the previous situations.3

The enteric nervous system is not only important for controlling intestinal motility but also for modulating secretory and absorptive processes.2 The neuropathy that causes dysfunction of the autonomic (enteric) nervous system is called the diabetic enteropathy and carries a true burden of symptoms for patients, although it is often under-diagnosed and under-treated. Its pathogenesis is still not totally understood but it is known that multiple underlying mechanisms are involved and can lead to a myriad of complications and the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract can be affected from mouth to rectum.4–6

Diarrhea is one of the most common symptoms of diabetic enteropathy. It is typically watery, voluminous, explosive and painless and occurs during both day and night.3 Although its symptoms may be relatively straightforward, patients may accept them and fail to disclose them to their doctors.1

Different studies estimate that the prevalence of diabetic diarrhea ranges between 8 and 22%, although its true incidence is probably much lower and its prevalence is higher in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.1,6

Known risk factors associated with diabetic diarrhea are long disease duration, high HbA1c levels, male sex, and autonomic neuropathy,1 all of which apply to our patient and indicate poor longstanding metabolic control.

Treatment of diabetic diarrhea starts with improving the glycemic control and involves mainly symptom relief, correction of fluid and electrolyte deficits, nutritional improvement and removal of medications that may be exacerbating symptoms.7

In our patient, the diarrhea had secretory characteristics because it continued despite a 24h fast, there was a high volume of feces per day, it occurred also at night and the osmotic gap was under 50mOsmol/kg. We decided to stop all medications possibly associated with diarrhea, such as diuretics, the statin and the protein pump inhibitor. Failure of conventional therapies even lent more support to the diagnosis of diabetic diarrhea, in addition to the exclusion of other diarrhea causes, so we decided to use clonidine, an alpha 2-adrenergic receptor agonist, known to be an important treatment of chronic diarrhea resistant to standard treatments.

Clonidine can inhibit gastrointestinal motor activity by activating the alpha 2-adrenergic receptors on enterocytes increasing fluid and electrolyte absorption and inhibiting secretion while at the same time decreasing bowel transit time. It has been used in treatment of chronic secretory diarrhea of unknown etiology, diarrhea associated with narcotics withdrawal, diabetic enteropathy, diarrhea caused by chemotherapy or graft versus host disease, among others and is the medication of choice in this category due to the less-central hypotensive effect.8

Octreotide (long-acting somatostatin analog) is another option in the diabetic patient with difficult to control diarrhea,7 but side effects include hypoglycemia that may be related to reduced secretion of counter-regulatory hormones. Furthermore, octreotide may inhibit exocrine pancreatic secretion and can therefore aggravate steatorrhea.6

After two months follow-up, the patient remained well, had gained 3kg and had no more intestinal disturbances. Our diabetic patient with high volume watery diarrhea responded to clonidine confirming the findings of previous case reports.

In conclusion, this case report reminds us that GI complications, such as diabetic enteropathy, are common in longstanding diabetes although still remain under-recognized. Its early identification and appropriate management are important for improving both diabetic care and quality of life of the affected patient.3

We gratefully thank Prof. Maria Francisca Moraes-Fontes for her guidance and support.