Difficult airway management remains a challenge and is a pillar of anesthesia training. At present, unsuccessful management of the difficult airway is a leading cause of complications in the practice of anesthesia, something that has led to regular updates to the management algorithms and the development of new technologies.

ObjectivesTo review the current state of videolaryngoscopy and its impact on difficult airway management.

MethodsWith the keywords Videotape Recording; Laryngoscopy; Airway Management; Intubation; Intratracheal; Obesity; Anesthesia. A non-systematic review in the following databases was conducted: Pubmed/Medline, SciElo, LILACS).

ResultsVideolaryngoscopes are a new technology for the management of difficult airways that so far have not replaced the standard airway management algorithm devices. Its main impact is better visualization of the laryngeal structures. However, there are still controversies regarding the ease and success of tracheal intubation. Evidence of its usefulness in difficult airway management is weak.

ConclusionKnowledge of these devices and their limitations is an alternative in difficult airway scenario, but its real value and safety for the patient is still not defined and continues to be researched.

el manejo de la vía área difícil continua siendo un reto y es uno de los pilares del entrenamiento en anestesia. En la actualidad, el manejo no exitoso de la vía aérea difícil representa una de las principales causas de complicación en el ejercicio de la anestesia que promueve la actualización regular de los algoritmos de manejo y al desarrollo de nuevas tecnologías.

Objetivospresentar el estado actual de los videolaringoscopios y su impacto en el manejo de la vía aérea.

Métodoscon las palabras claves: Grabación en video Laringoscopia, Intubación intratraqueal; Vía aérea difícil; Obesidad; Anestesia; Emergencias se realizó una revisión no sistemática en bases de datos (PubMed/Medline, SciElo, Lilacs).

Resultadoslos videolaringoscopios son una tecnología adicional para el manejo de la vía aérea que hasta el momento no han demostrado sustituir los dispositivos estándares expuestos en el algoritmo de manejo de la vía aérea. Su principal impacto está determinado por la mejoría en la visualización de las estructuras de la laringe sin embargo aún hay controversias respecto a la facilidad y éxito de la intubación endotraqueal. La evidencia de su utilidad en el manejo exitoso de la vía aérea difícil es débil.

Conclusionesel conocimiento de estos dispositivos así como sus limitaciones constituye una alternativa en el escenario de la vía aérea difícil, pero su valor real y la seguridad que representa para el paciente aún no se han definido y continúa en investigación.

Difficult airway is defined as the clinical situation in which a trained anesthesiologist experiences difficulty in ventilation with a face mask or tracheal intubation1–3. Its incidence in the general population is between 1.15 and 3.8%, and that of failed intubation is 0.13–0.3%4,5. The situation may result in complications as severe as bronchoaspiration, lesions in the upper airway, cerebral hypoxia, and death1–3,5.

Awareness of new alternatives for securing the airway is a constant necessity5. Video laryngoscopes are a new generation of devices that allow direct visualization of the glottis and have recently been included in several societies’ algorithms for airway management. In our context, however, there are few publications about their use, success rate, and safety.

MethodologyA non-systematic literature review in English and Spanish in the databases PubMed/Medline, SciElo, and Lilacs with the following MeSH and DeCS terms: Videotape Recording; Laryngoscopy; Airway Management; Intubation, Intratracheal; Obesity; Anesthesia. We proceeded to read each article and review the relevant references related to videolaryngoscopes in airway management that allowed us to describe their main characteristics and impact. Finally, 51 articles were chosen through consensus among the three researchers.

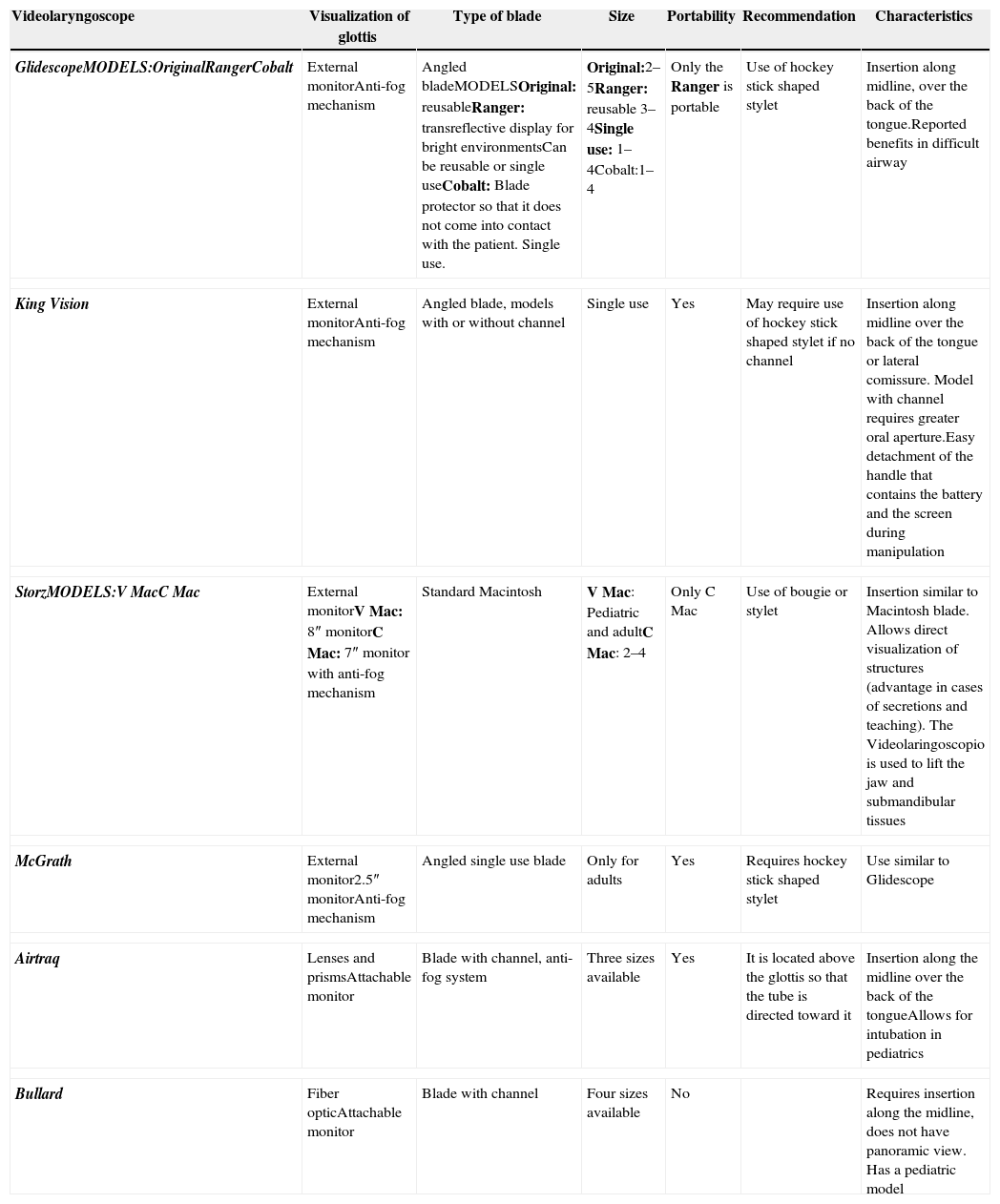

ResultsThe tubular, remote view of the glottis with direct laryngoscopy provides a 15° visual field. This can be extended to between 45° and 60° with videolaryngoscopes.6–8 The videolaryngoscope models can be classified according to the mechanism for visualizing the glottis and the design of the blade (Table 1).Depending on the mechanism for visualizing the glottis, they can be:

- 1.

Devices with a miniature video camera incorporated into the distal part of the laryngoscope blade. From here, the image is transmitted to an external screen. Example: McGrath, Glidescope, Storz, King Vision6,7,9.

- 2.

Devices in which the image is transmitted through a fiber optic bundle or through a system of prisms to a storage device, such as a video system or lens. Examples: Airtraq (lenses and prisms) and Bullard (fiber optics)6,7,9.

- 1.

Videolaryngoscopes with standard Macintosh blades are inserted using the same technique as in direct laryngoscopy. Example: Storz7,9.

- 2.

Videolaryngoscopes with angled blades. They have an extra curve that allows for visualization through the camera only. Examples: Glidescope and McGrath7,9.

- 3.

Videolaryngoscopes with channel blades. They have a central channel through which the endotracheal tube (ETT) can be preloaded, which allows for insertion once the glottic opening is viewed. Examples: King Vision, Airtraq, and Bullard7,9.

Videolaryngoscope characteristics.

| Videolaryngoscope | Visualization of glottis | Type of blade | Size | Portability | Recommendation | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GlidescopeMODELS:OriginalRangerCobalt | External monitorAnti-fog mechanism | Angled bladeMODELSOriginal: reusableRanger: transreflective display for bright environmentsCan be reusable or single useCobalt: Blade protector so that it does not come into contact with the patient. Single use. | Original:2–5Ranger: reusable 3–4Single use: 1–4Cobalt:1–4 | Only the Ranger is portable | Use of hockey stick shaped stylet | Insertion along midline, over the back of the tongue.Reported benefits in difficult airway |

| King Vision | External monitorAnti-fog mechanism | Angled blade, models with or without channel | Single use | Yes | May require use of hockey stick shaped stylet if no channel | Insertion along midline over the back of the tongue or lateral comissure. Model with channel requires greater oral aperture.Easy detachment of the handle that contains the battery and the screen during manipulation |

| StorzMODELS:V MacC Mac | External monitorV Mac: 8″ monitorC Mac: 7″ monitor with anti-fog mechanism | Standard Macintosh | V Mac: Pediatric and adultC Mac: 2–4 | Only C Mac | Use of bougie or stylet | Insertion similar to Macintosh blade. Allows direct visualization of structures (advantage in cases of secretions and teaching). The Videolaringoscopio is used to lift the jaw and submandibular tissues |

| McGrath | External monitor2.5″ monitorAnti-fog mechanism | Angled single use blade | Only for adults | Yes | Requires hockey stick shaped stylet | Use similar to Glidescope |

| Airtraq | Lenses and prismsAttachable monitor | Blade with channel, anti-fog system | Three sizes available | Yes | It is located above the glottis so that the tube is directed toward it | Insertion along the midline over the back of the tongueAllows for intubation in pediatrics |

| Bullard | Fiber opticAttachable monitor | Blade with channel | Four sizes available | No | Requires insertion along the midline, does not have panoramic view. Has a pediatric model | |

The insertion of videolaryngoscopes differs from that of conventional laryngoscopes. The alignment of the oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal axes is not required (Fig. 1). Achieving an adequate oral aperture is essential, since the device must enter along the midline, following the shape of the palate and the posterior pharynx in a way similar to the insertion of laryngeal masks7,10,11.

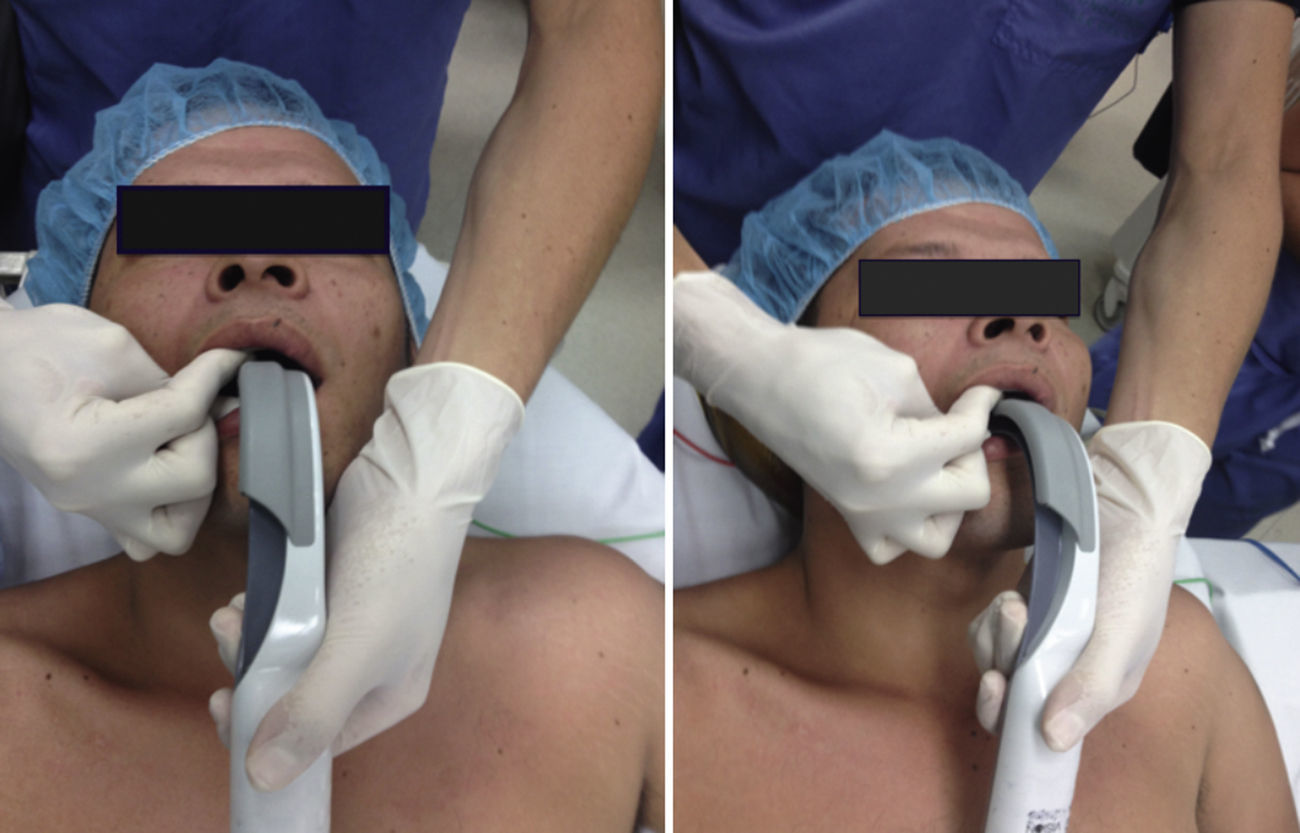

A frequent difficulty with the use of these devices arises during the insertion of the ETT due to the lateral right displacement of the tongue or to an inadequate oral aperture. For this, the jaw-thrust maneuver is recommended with finger pressure on the incisors (Fig. 2)7,10,11.

Even with an adequate visualization of the glottis, the insertion of the ETT may be difficult10,11. For this reason, videolaryngoscopes have been designed that have a channel for the insertion and movement of the tube. Also is recommended the use of stylet with a 60° angle in the distal part of the ETT in a shape similar to that of a hockey stick, entering through the oral comissure, and performing the BURP maneuver (Back Up Right Pressure)10,11. Advancing the ETT may also present difficulties since the angle of incidence between the laryngoscope blade and the trachea may make the tube hit the tracheal cartilage12.

GlidescopeCurrently, there are three models of this type of videolaryngoscope: the original Glidescope, the Glidescope Ranger, and the Glidescope Cobalt13–16. The original Glidescope is a reusable plastic device with a handle similar to that of a conventional laryngoscope, and a blade with a 60° angle in the middle and a digital camera in the distal part of the blade14. The Glidescope Ranger has a portable design with a smaller, 3.5″ screen with a transreflective display that allows the operator to view the anatomy in a brightly-lit environment, such as in pre-hospital or military settings16. The Glidescope Cobalt has a blade similar to the Macintosh blade with a 60° angle in the tip. It has a reusable color video camera with a powerful light source and a transparent plastic disposable blade through which the video baton is inserted so that direct contact between the camera and the patient can be avoided. As such, it does not require disinfection14.

Studies on Glidescope have shown success rates of more than 94%, with intubation times under one minute, and improvement of the view of the vocal cords by one to two degrees13,16,17 even in patients with restricted cervical mobility, such as those with ankylosing spondilytis18.

A meta-analysis that compared endotracheal intubation with Glidescope to intubation with direct laryngoscopy demonstrated an improvement in glottic visualization with Glidescope. This benefit increases in patients with difficult airway. Nevertheless, a greater intubation success rate and lower intubation time was only found with Glidescope when performed by inexperienced personnel. No difference was found compared to direct laryngoscopy when intubation was performed by experienced personnel19. Alteration of neck anatomy was reported as an important predictor of failure with Glidescope20.

King VisionThe King Vision videolaryngoscope is a device with a 2.4″ LED screen (160° panoramic view), a disposable blade, and a video connection. It has two types of blades: a standard blade that allows for free manipulation of the ETT with a 60° angled stylet and that requires a minimum oral aperture of 13mm and insertion along the midline; and a blade with a channel through which the ETT may be introduced and that requires a minimal oral aperture of 18mm with insertion along midline or laterally (Fig. 3). If the tube hits the right arytenoid cartilage, rotating the videolaryngoscope to the left until obtaining alignment with the entry of the glottis is recommended. Once the ETT has entered the larynx, the stylet should be partially withdrawn and the tube should be rotated 90° to avoid contact with the tracheal cartilages. It is also possible to insert a bougie and run an ETT through it21.

In a study conducted on inexperienced personnel, the King Vision without a channel showed a higher success rate and a longer intubation compared to the device with the channel and the conventional laryngoscope. Between the latter two, there was no difference22.

In the simulated difficult airway setting, the King Vision had a greater success rate and better glottis visualization compared to the traditional laryngoscope23.

Storz videolaryngoscopeThis videolaryngoscope was designed by Karl Storz who modified the Macintosh blade and the handle from a traditional laryngoscope. It has an 8″ camera adapted to the handle, which increases the image of the anatomical structures, and a Macintosh blade containing a light that is directed toward the portion of the larynx to be viewed7. Its insertion is similar to that of the traditional laryngoscope, with the possibility of directly viewing structures during the process.

There are two models of this type of videolaryngoscope: the V Mac, that features a camera incorporated into the laryngoscope handle, and the C Mac, the newest model with a better image (Fig. 4) and a memory card7.

The Storz videolaryngoscope has proven useful in teaching laryngoscopy as it permits a direct view of the anatomical structures and the results of the external manipulation of the larynx. A study by Storz showed that intubation attempts were successful, with a short learning curve, and greater external manipulation of the larynx when difficult airway predictors were present24. In addition, it improved the visualization of the glottis in as many as 40% of patients25, has a success rate of 93% on the first attempt, and required less external larynx manipulation and bougie use compared to direct laryngoscopy, but with longer intubation times26.

AirtraqAirtraq is a rigid disposable laryngoscope with two channels: one for the ETT and the other for a cold-light source with anti-fog lenses, prisms, and mirrors that transmit the image to a screen located on the opposite end or to an external Bluetooth connected monitor (Fig. 5)7.

Different sizes are available that allow for tube diameters ranging from 2.5mm up to 8.5mm and has presentations for nasal intubation. 35–37F double-lumen tubes have also been inserted with the Airtraq7.

Studies have shown that the learning curve for personnel trained in laryngoscopy is shorter, with a shorter intubation time, greater number of successful intubations, and less external larynx manipulation. In patients with manual alignment of the cervical spine, the Airtraq requires less vertebral movement as demonstrated in radiological studies27,28.

The limitations for its use are: an oral aperture of at least 20mm, a reduced thyromental distance, blood or secretions in the airway, and tearing of the balloon cuff due to insufficient lubrication in the tube channel27.

Mcgrath videolaryngoscopeThe McGrath videolaryngoscope consists of a blade called a CameraStick, whose length can be modified for use in children and adults. It has a source of LED light and a video camera in its distal tip. A disposable blade covers the CameraStick and can be used as a leaver in the glottic cavity. Attached to the handle is a 2.5″ LCD screen whose angle can be changed7.

There are reports that the McGrath videolaryngoscope can convert a Cormack-Lehane grade 3 or 4 glottis into a 1 or 2, with success rates of up to 95%29.

Other studies have shown that, although the glottis visualization improves with the use of the McGrath, the time required, the number of failed intubations, and external manipulations needed were greater compared to the Macintosh laryngoscope30.

There have been descriptions of lesions in the oral cavity produced when the observer moves the tube without visualizing the structures through which it is passing through and it implies a learning curve to be used in cases of difficult airway30.

Bullard laryngoscopeThe Bullard rigid fiber optic laryngoscope can be introduced into patient's mouth with a minimum oral aperture of 6mm so that a glottic view can be achieved without hyperextension of the cervical spine. It consists of a metallic curved L-shaped blade of which the distal tip can be attached to a plastic piece to make it longer for intubations in large patients.

A light source, the optical lens, and a channel for aspiration or oxygen flow emerge from the posterior part of the blade. This allows for the attachment of the video camera and has different presentations for newborns and pediatric patients31,32.

The Bullard laryngoscope does not have a panoramic view, and if it is not introduced along the midline, the vocal cords may not be seen. In simulated settings of cervical trauma and rapid sequence intubation, it is effective in securing the intubation, but with prolonged times33. Compared to laryngeal mask intubation, it shows a non-significant tendency of greater effectiveness in intubation with an aligned cervical spine34. As with other devices, it involves a learning curve and the recommended setting is with non-urgent airways35. It can be used for nasal intubation (Figs. 6 and 7).

DiscussionDifficult airway management continues to be a challenge in the practice of anesthesia. The identification of a Cormack-Lehane grade 3 or 4 does not closely correlate to the difficulty of intubation since the majority of these patients can be successfully intubated with the help of a stylet or a bougie36,37. However, the optimization of larynx visualization with devices like videolaryngoscopes does not guarantee successful intubation. The efficacy of videolaryngoscopes in cases of difficulty airway has limited evidence. Devices like the Airtraq, the Glidescope, and the Bullard have been recommended in cases where difficult airways and failed intubation occurs with direct laryngoscopy, but in experienced hands38–40. It has been shown that success with videolaryngoscopes is related to experience in management, with a learning curve that generally does not exceed 10 patients.

Studies that compare the different types of videolaryngoscopes to conventional laryngoscopy have so far shown an improvement in the visualization of structures to approximately grades 1 or 2. However, there continues to be controversy in the duration and success rate of the intubation36,39,41. In inexperienced hands in the emergency setting, the use of videolaryngoscopes has been shown to increase the success rate for intubation after the first attempt42–45.

In obese patients, in which intubation can be difficult in up to 15% of patients46, videolaryngoscopes have shown improvement in the visualization of the larynx with no difference found in intubation times47,48. In a large percentage of patients (3.7%)49, despite the good visualization, intubation was not possible.

Up to the present, counterindications for the use of videolaryngoscopes have not been described, and the associated complications, such as lesions in the airway, are only starting to be described49. Altered anatomy has been mentioned as a possible predictor of failure with the Glidescope20 and advancing the tube without visualizing the structures through which it is passing can be an important cause of complications. Likewise, there are no studies published in terms of cost analysis that compare videolaryngoscopes with direct laryngoscopes. Nevertheless, there are publications that compare disposable and reusable videolaryngoscopes, showing similar values50. Apparently the net cost of a videolaryngoscopy is higher than that of a direct laryngoscope in terms of its price, maintenance, battery, hygiene, training, etc. That said, more cost–effectiveness studies are needed to support this theory. Compared to fibrobronchoscopy, they are less expensive, but the evidence of their efficacy in difficult airway situations continues to be weak. Therefore, fibrobronchoscopy continues to be the gold standard.

ConclusionAlthough recently the use of videolaryngoscopes has been mentioned in the algorithm for difficult airway management1,51 with type A evidence of improvement in laryngeal visualization, controversies continue to persist with regard to the value of this device in the management of difficult airway and safety for patients. Therefore, it continues to be a topic of investigation51. For the time being, intubation with fibrobronchoscopy in conscious patients continues to be the safest method of managing an anticipated difficult airway1.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Chaparro-Mendoza K, Luna-Montúfar CA, Gomez JM. Videolaringoscopios: ¿la solución para el manejo de la vía aérea difícil o una estrategia más? artículo original. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2015;43:225–233.