the bispectral index monitoring system (BIS) was introduced in the United States in 1994 and approved by the FDA in 1996 with the objective of measuring the level of consciousness through an algorithm analysis of the electroencephalogram (EEG) during general anesthesia.

This novelty allowed both the surgeon and the anesthesiologist to have a more objective perception of anesthesia depth. The algorithm is based on different EEG parameters, including time, frequency, and spectral wave. This provides a non-dimensional number, which varies from zero to 100; with optimal levels being between 40 and 60.

ObjectivesPerform an analysis of the advantages and limitations of the anesthetic management with the bispectral index monitoring, specifically for the management and prevention of intraoperative awareness.

MethodologyA non-systematic review was made from literature available in PubMed between the years 2001 and 2015, using keywords such as “BIS”, “bispectral monitoring”, “monitoreo cerebral”, “despertar intraoperatorio”, “recall” and “intraoperative awareness”.

ResultsA total of 2526 articles were found, from which only the ones containing both bispectral monitoring and intraoperative awareness information were taken into consideration. A total of 68 articles were used for this review.

ConclusionBIS guided anesthesia has documented less immediate postoperative complications such as incidence of postoperative nausea/vomit, pain and delirium. It also prevents intraoperative awareness and its complications.

El índice de monitoreo biespectral (BIS) fue introducido en Norte América en 1994 y aprobado por la FDA en 1996 con el objetivo de medir el nivel de conciencia realizando un análisis algorítmico del electroencefalograma (EEG) durante la anestesia general.

Esta novedad permitió que tanto el cirujano como el anestesiólogo tuvieran una percepción más objetiva de la profundidad anestésica. El algoritmo está basado en diferentes parámetros del EEG, incluyendo tiempo, frecuencia y onda espectral. Esto provee un número no dimensional, que varía desde cero, hasta 100; siendo los niveles óptimos entre 40 y 60.

ObjetivosRealizar un análisis de las ventajas y limitaciones del manejo anestésico con el monitor de análisis biespectral, específicamente en el manejo y prevención del despertar intraoperatorio.

MetodologíaSe realizó una revisión no sistemática de literatura disponible en PubMed entre los años 2001-2015, utilizando palabras clave como “BIS”, “bispectral monitoring” “monitoreo cerebral”, “despertar intraoperatorio” “recall” y “intraoperative awareness”.

ResultadosSe encontraron un total de 2526 artículos, de los cuales solo se tomaron en cuenta aquellos que contenían información de tanto monitoria biespectral como despertar intraoperatorio. Un total de 68 artículos fueron utilizados para esta revisión.

ConclusiónEn la anestesia guiada por BIS se han documentado menores complicaciones postoperatorias inmediatas como la incidencia de nausea/vómito, dolor y delirium. Además de prevenir el despertar intraoperatorio y sus complicaciones.

Measuring anesthetic depth has always been a substantial necessity, even from the beginning of anesthesia with ether in 1847.

Currently, the Bispectral Index (BIS) is the most frequently used technology for monitoring anesthetic depth. Its objective, based on a mathematical algorithm, is to measure the level of consciousness through the use of an EEG of the patient under general anesthesia to thereby evaluate its effects directly at a cerebral level.1

Among the advantages of its use are anesthetic titration based on brain activity by which the incidence of intraoperative awareness (IA) and anesthetic consumption are reduced; this leads to quick recovery.2,3

BIS values are related to EEG activity. The beta wave (β) is related to awareness at BIS values between 100 and 80 and to a state of sedation with general anesthesia in the range of 60–40. Deep anesthesia is reflected with delta waves (δ) and a range between 40 and 20 on the BIS monitor, while burst suppression is reflected by a range of 0 and 20. An isoelectric line on the encephalogram corresponds to a value of 0 on the monitor.4–7

The meta-analysis carried out by Punjasawadwong et al. compared BIS use to standard anesthetic care in order to determine if there was a reduction in anesthetic consumption, recovery time, incidence of IA, and hospital costs. 12 studies and 4056 patients were considered and it was demonstrated that the use of BIS lowers propofol levels by 1.3mg/kg/h; minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) by 0.17; extubation time by 3.05min; recovery time in the postanesthetic care unit by 6.83min; and IA by 65.4%.8 In a later update to this study, a result of equivalency in the reduction of IA was obtained when comparing anesthetic depth guided by BIS monitoring and anesthetic depth guided by the concentration of anesthetic gas at the end of the tidal volume .9

Monk et al. researched the relationship between anesthesia management and mortality one year after non-cardiovascular surgery, finding an increase of 24.4% in mortality per hour in which the BIS values were lower than 45 (p=0.0121).10 Similarly, Leslie et al., in their study, “B-Aware”, demonstrated that when BIS values did not go below 40 for more than 5min, there was an increase in survival to 30 days.11 The importance of monitoring of anesthetic depth with BIS has not been very well explored. Studies like “B-Unaware” and “BAG-RECALL”, performed with patients undergoing heart surgery, demonstrated a probable relationship between low BIS values and mortality in the medium term. However, this was not associated with an increase in the total dosage of anesthetics.12,13

One of the most important retrospective studies in the United States was developed by Sessler et al. and investigated the relationship between length of hospital stay and mortality after 30 days in patients that presented a “triple low” in values of mean blood pressure (<75mmHg), BIS (<45), and CAM (<0.8).

Of the 24,120 patients included in the study, 6% presented “triple low” during the surgery. These patients experienced a prolonged hospitalization and mortality increased by two. It was concluded that mortality after 30 days increased when the duration of the “triple low” was greater than 30min.14 Later, however, the results of this study were questioned by Kertai et al.:15 the “triple low” continues to be a subject of discussion.16–18

In cardiovascular surgeries, the monitoring of anesthetic depth is a challenge for the anesthesiologist. The use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) predisposes the patient to presenting IA for different reasons: during CPB, blood pressure is determined by the extracorporeal circulation pump and the patient lacks a heart rate. As such, anesthetic depth is difficult to correlate.19

Anesthetic depth monitored with BIS during heart surgery does not appear to have a significant impact in terms of a reduction of extubation time, time in the ICU, and hospital stay.20,21 Likewise, the use of total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) produces changes in pharmacokinetics, increasing the risk of complications. The use of cerebral activity monitors becomes essential in these circumstances.22

Another of the advantages of using BIS is the possible reduction of delirium and cognitive decline, both immediate (1 week) and late (3 months).23–25

ObjectivesPerform an analysis of the advantages and limitations of the anesthetic management with the bispectral index monitoring, specifically for the management and prevention of intraoperative awareness.

MethodologyA non-systematic review was made from literature available in PubMed between the years 2001 and 2015, using keywords such as “BIS”, “bispectral monitoring”, “monitoreo cerebral”, “despertar intraoperatorio”, “recall” and “intraoperative awareness”.

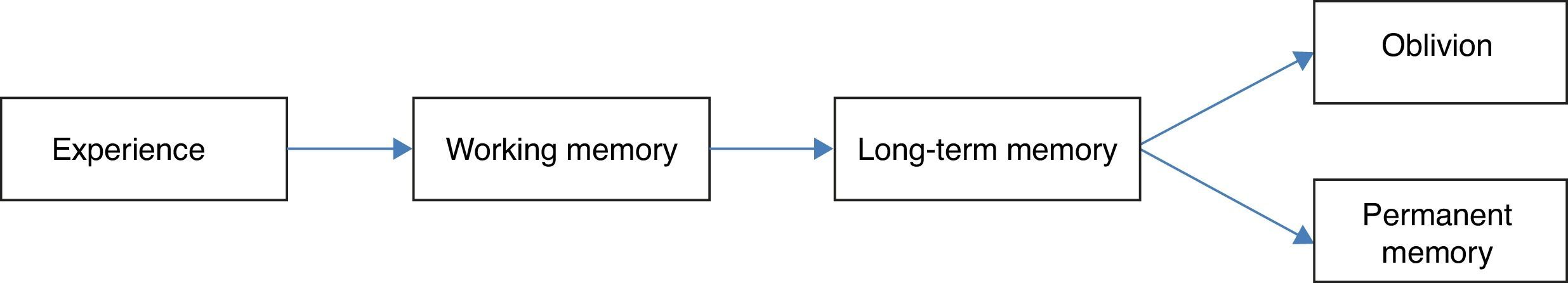

Intraoperative awarenessMemory is the capacity to retain and relive impressions or to recognize previous experiences. It is characterized by four steps: codification, consolidation, storage, and recovery. In chronological order, sensory stimuli are converted in memory (codification), followed by transfer from short term memory to more stable long term memory prior to entrance into neocortical areas (consolidation). Later, memory is represented by an interconnected neuron network through the neocortex that join together for storage and finally recovery.26,27

There are two types of memory, both of which have been widely studied. First, explicit memory (also know as controlled or declarative memory) that makes use of structures in the medial temporal lobe, like the hippocampus and cortical structures, that are essential for formation, reorganization, consolidation, and storage.28–30 The second, implicit memory (also called automatic or non-declarative) refers to changes in behavior or response to stimuli without a knowledge or memory of the context in which these stimuli appeared.28,29 It includes multiple areas of the brain: the cerebellum, the striatum, and the midbrain. The amygdalae modulate emotional learning in the cortex and the hippocampus, being necessary for the storage and recovery of memories (Fig. 1).26,31

Anesthetics do not affect implicit memory, but it is thought that they due have an influence on explicit memory during general anesthesia, usually due to an improper anesthetic levels.32 The molecular mechanism by which anesthetics affect memory and learning are a subject of study; their effect on type A γ-aminobutyric receptors (GABAA) appears to inhibit and block the normal memory process.26,33

IA is defined as the experience and specific memory of a sensory perception during surgery.34 The patients can remember intraoperative events spontaneously or in response to specific questions about the event, and this memory can occur immediately after the surgery or days after the surgery.35 The first documented case was in 1950 by Winterbottom.36,37 The current incidence is subject to debate due to methodological differences in the studies performed and the wide variety of perceptions reported by patients.38,39 Nevertheless, the incidence presented in the 5th National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anesthetists of the United Kingdom (NAP5) is 1:19,000.40

In patients with a high risk of IA, as well as patients under TIVA, the incidence can be as high as 1%.41,42 Obstetric anesthesia is the subspecialty with the greatest incidence of IA; some risk factors attributed to this are: use of thiopental, rapid induction, difficulty in airway management, obesity, emergency cases, and cases performed by personnel in training, among others.43,44

IA represents 2% of lawsuits in the Closed Claims database of the American Society of Anesthesia (ASA).45 In a series of interviews, it was shown that more that 50% of patients expressed a fear of “waking up in surgery” and that 65% of those that experienced this complication did not tell their anesthesiologist or did not have the opportunity to.46,47

Pandit et al. studied 153 cases of IA during general anesthesia. 47% of the cases occurred during the induction of anesthesia, 30% during surgery, and 23% before recovery.48 The most commonly reported sensory perceptions were auditory (70%) and tactile (72%), while emotional reactions presented in 65% of the cases (p<0.05).47 IA can lead to consequences of post-traumatic stress disorder in up to 71% of the population, appearing between 2h and 30 days after the event.49,50

Main causesThe most important causes of IA are as follows. (1) Anesthetic underdosage given patient needs.34,51 The incidence of IA is 0.10% when neuromuscular relaxants are not present, compared to 0.18% when they are.52 This is related to an insufficient dose of anesthetics because the patient may remain paralyzed by conscious since the necessary anesthetic concentration to block motor response is much greater than that required to block explicit memory.30,53 Nevertheless, removing it is often not feasible because muscle relaxation is important for the surgical process.54

(2) Patient resistance to anesthesia, age, tobacco use, obesity, chronic use of amphetamines, alcohol, and opioids can make the patient need an increase in the dose of anesthetics.51,55 (3) Mechanical problems that result in an inadequate anesthetic delivery: intravenous block, an empty gas cylinder, or air caught in the ventilator.55 (4) Patients with a low physiologic reserve and a low anesthetic requirement.

The use of medications like preoperative benzodiazepines could help, by inhibiting the formation of anterograde memory.56 Its use has yet to be studied.29

DiagnosisSurveys and interviews like the “modified Brice protocol” (MBP) evaluate the characteristics of the events that occur before, during, and after anesthesia and are useful for the diagnosis of IA.57 Different studies have found an incidence of IA of 79%, between 33–50% and 28% in the post-anesthetic care unit 7 and 14 days after the procedure respectively, highlighting the importance of its evaluation, even weeks after the anesthetic event.

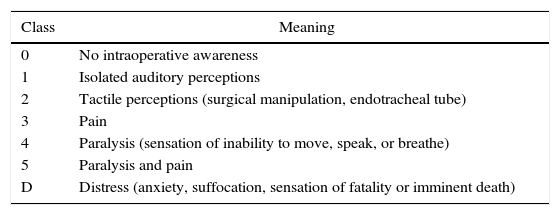

The diagnosis od IA can be subdivided into six categories (Table 1). Its classification is important for preventing sequelae in the long term, such as post-traumatic stress syndrome that usually manifests itself as alterations to sleep patterns, recurring nightmares, flashbacks, and anxiety.49,58,59

Classification of intraoperative awareness according to Mashour. ds.

| Class | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 0 | No intraoperative awareness |

| 1 | Isolated auditory perceptions |

| 2 | Tactile perceptions (surgical manipulation, endotracheal tube) |

| 3 | Pain |

| 4 | Paralysis (sensation of inability to move, speak, or breathe) |

| 5 | Paralysis and pain |

| D | Distress (anxiety, suffocation, sensation of fatality or imminent death) |

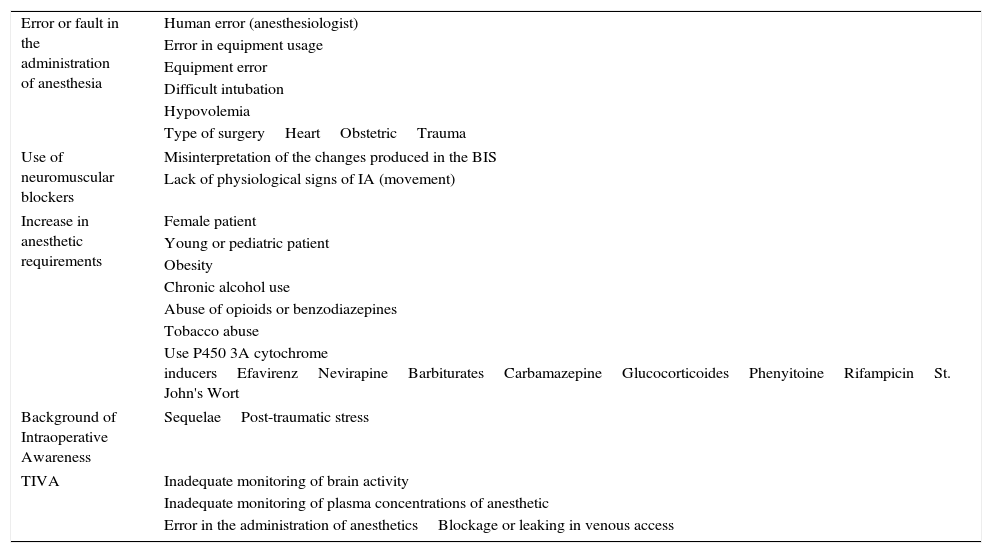

Different characteristics exist that can make a certain individual more susceptible to IA: the feminine sex, use of anticonvulsive medications, ASA≥4, ejection fraction>40%, a history of IA, difficult intubation, cardiovascular surgery, tobacco addiction, and alcohol consumption (Table 2).13,34,35 Avidan et al. chose patients with these risk factors, later randomizing them between anesthesia guided by BIS or MAC. The IA was evaluated with MBP at 72h and at 30 days post-extubation. The results demonstrated that more patients from the BIS group showed IA, but that these differences were not clinically significant (p=0.98).13

Risk factors for intraoperative awareness.

| Error or fault in the administration of anesthesia | Human error (anesthesiologist) |

| Error in equipment usage | |

| Equipment error | |

| Difficult intubation | |

| Hypovolemia | |

| Type of surgeryHeartObstetricTrauma | |

| Use of neuromuscular blockers | Misinterpretation of the changes produced in the BIS |

| Lack of physiological signs of IA (movement) | |

| Increase in anesthetic requirements | Female patient |

| Young or pediatric patient | |

| Obesity | |

| Chronic alcohol use | |

| Abuse of opioids or benzodiazepines | |

| Tobacco abuse | |

| Use P450 3A cytochrome inducersEfavirenzNevirapineBarbituratesCarbamazepineGlucocorticoidesPhenyitoineRifampicinSt. John's Wort | |

| Background of Intraoperative Awareness | SequelaePost-traumatic stress |

| TIVA | Inadequate monitoring of brain activity |

| Inadequate monitoring of plasma concentrations of anesthetic | |

| Error in the administration of anestheticsBlockage or leaking in venous access | |

The “B-aware” study also study patients with a high risk of presenting IA. Perioperative care and the use of anesthetics were not modified. Patients could be monitored with BIS during the surgery or following the standard protocol of each hospital. A previously structured questionnaire was applied 2–6h, 24–36h, and 30 days after surgery.60 A reduction of 82.2% (95% IC 17–98%) in IA was observed in those patients given BIS guided anesthesia. Of those patients that had IA, the ranges in the monitor ranged between 55 and 82 and so it was concluded that constant attention to the monitor is vital.60

In contrast with the previous results, the study B-Unaware found no difference in the incidence of IA in 1941 patients with a high risk of presenting it.12

Many other studies have been carried out, proposing the same type of approach as in the MBP study, in which no difference has been demonstrated between the group under BIS-guided anesthesia and the group managed with the standard protocol.61 Despite this, they were able to demonstrate that MBP, as a diagnostic tool for IA, is superior to any other measure (p<0.0001).62

The incidence of IA during TIVA has also been studied.56,63 In diverse studies, the anesthetic depth guided by the MAC value has been shown to have a low incidence of IA.13,34 By contrast, in TIVA, the plasma concentration at which 50% of the patients do not respond to the surgical incision in the skin (PC50) is not clinically practical and cannot be carried out in real time.9,64 This is quantified by pharmacological models with infusion pumps, applications for mobile devices, or nomograms. Upon comparing BIS (Group A) with standard management (Group B) and applying MBP on the first and fourth postoperative days, four patients in group A presented IA (0.14%) while 15 patients from group B presented IA (0.65%). BIS-guided TIVA presented a reduction in the incidence of IA of 78%.65

PreventionThere are three basic aspects necessary to prevent IA: (1) observation of the patient including clinical signs like some type of movement, sweating, tearing; (2) conventional intraoperative monitoring including vital signs and their relationship with the sympathetic nervous system, translating into an increase in blood pressure and heart rate; and (3) monitoring of cerebral function.66

There are also multiple suggestions for significantly reducing IA:

- (1)

Premedicate all patients with pharmaceuticals that have a sedative affect and that help to diminish IA incidence (e.g. benzodiazepines), particularly in the case of superficial anesthesia or that of a short duration. These medications block the anterograde memory and cognitive processes in a way that is proportional to the dose and speed of administration. An oral dosage of 0.2–0.3mg/kg, one hour prior to surgery may give these results.29,40

- (2)

Give adequate doses of anesthetics at induction, immediately after endotracheal intubation and even when the first surgical incision is performed.

- (3)

Avoid or reduce the use of neuromuscular blockers to manage to evaluate objectively the patient's motor area.40

- (4)

During the maintenance of general anesthesia with volatile agents, maintaining a MAC greater than or equal to 0.7% is recommended.34

- (5)

In obstetric patients, those with severe trauma, or difficult intubation, the use of amnesic and opioid medications should be considered.40,67

- (6)

A periodic check-up of the anesthesia administration equipment and of the venous accesses should be carried out.40,68

- (7)

Discuss with the patient the possibility of IA, especially if he or she has more than one risk factor, thereby avoiding legal problems in the future.40,68

- (8)

Know the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and the bioavailability process of the anesthetic you are working with.68

The controversy that exists in the multiple studies that have been performed still leaves much to be studied when it comes to this complex theme of intraoperative monitoring. What is certain is that a clear advance in the medical field has been seen from the introduction of this method for guiding anesthesia. It does not only help the patient as an individual, improves their outcomes and minimizes post-operative complications, it also is a clear advance in the maximization of resources in hospital networks, reduces costs, and lowers rates of morbidity and mortality due to surgical interventions.

At the time of pre-anesthetic evaluations, all risk factors that the individual presents or that make him more susceptible to IA -or if they have experiences IA before- should be taken into account so that effective preventative measures can be taken in order to avoid this complication.

FundingThe authors did not receive sponsorship to undertake this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Castellon-Larios K, Rosero BR, Niño-de Mejía MC, Bergese SD. Uso de monitorizacion cerebral para el despertar intraoperatorio. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2016;44:23–29.