One of the primary aspects of pediatric anesthesia is airway management. Because of the anatomic differences, this population is more vulnerable to adverse effects produced by the devices designed for their management. Many of the anatomic descriptions are based on the knowledge developed mainly as a result of cadaveric dissections. Imaging of the pediatric airway has been available for almost a decade, and it has shown that the glottis is the narrowest portion and that the larynx is more cylindrical than tapered. These findings impact the selection of airway management devices.

MethodsThe new anatomic concepts pertaining to the pediatric airway were reviewed, and the advantages and disadvantages of the use of cuffed or uncuffed endotracheal tubes (ETT) were analyzed.

Results and conclusionsThe enhanced knowledge of the pediatric anatomy permits the use of devices suitable to the characteristics of the individual airway. The development of cuffed tubes for pediatric practice is advancing rapidly, although there is no current consensus for their use. However, publications coincide on the need to standardize designs and to measure cuff pressure.

Uno de los aspectos de mayor relevancia en anestesiología pediátrica es el manejo de la vía aérea (VA). Las diferencias anatómicas de esta población hacen que sea más susceptible a efectos adversos de dispositivos diseñados para su manejo. Muchas de las descripciones anatómicas actuales se basan en hallazgos de hace más de medio siglo derivados de disecciones en cadáveres. Desde hace casi una década hay estudios de imágenes de VA en niños que identifican la glotis como la porción más angosta, y la laringe más cilíndrica que cónica. Estos hallazgos tienen impacto al escoger dispositivos de manejo de VA.

MétodosSe realizó una revisión de nuevos conceptos anatómicos de VA pediátrica y se analizaron pros y contras del uso de tubos endotraqueales con y sin balón.

Resultados y conclusionesEl mayor conocimiento de la anatomía pediátrica permite usar dispositivos acordes a las características de la VA del niño. El desarrollo de tubos con balón en la práctica pediátrica es más frecuente, aunque no hay consenso actual para su utilización. En lo que concuerdan las publicaciones es en estandarizar diseños y medir la presión del balón.

One of the most important aspects in pediatric anesthesiology is airway management. For this reason, the adequate use of devices and equipment is a key factor for reducing complications.

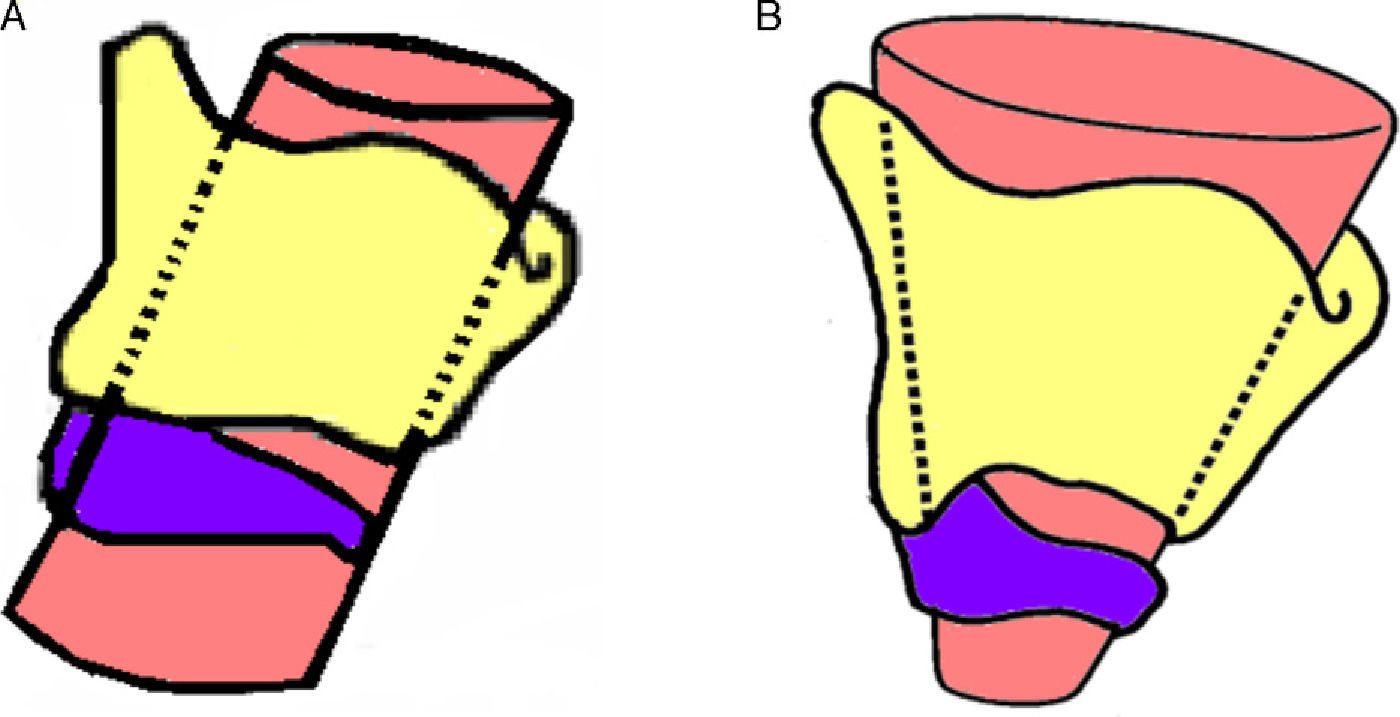

Airway anatomy is different in children and adults, in particular in children under 2 years of age. This population has small nares, a large tongue, and a larger head in relation to the body.1 In the newborn the neck is short, and the epiglottis is omega-shaped, lax and thrust backwards. The glottis is localized at the level of C3–C4. The larynx has been described as tapered, with its narrowest portion at the level of the cricoid cartilage, in contrast with the cylindrical adult larynx3 (Fig. 1). However, new evidence has shown that the latter is perhaps not accurate.

This article reviews new concepts regarding the shape of the pediatric larynx and analyzes the pros and cons of the use of cuffed or uncuffed ETT for the management of the airway, based on these new approaches.

What has been the evolution of the anatomical concepts pertaining to the pediatric larynx?In 1951, Eckenhoff2 wrote about the anatomical considerations of the pediatric larynx and their implications for anesthesia. His article was based on descriptions made half a century before by Bayeux,4 who reported the findings from anatomic dissections in 15 bodies of children between 4 months and 14 years of age, together with their corresponding plaster models.

Eckenhoff describes the cricoid cartilage as a rigid structure that cannot be distended in order to pass the ETT, and describes how its parts come together to form a ring around the larynx. Although he was clear in stating the risk of extrapolating cadaver findings to live human beings, some anesthesiology textbooks have used those anatomical descriptions of the pediatric airway as reference.6

In 2003, Litman et al.,5 in a study of magnetic resonance imaging, determined the cross-sectional and anteroposterior (AP) diameter at the vocal cords and the cricoid cartilage in 99 children under 14, using deep sedation and spontaneous breathing. In all of them, the narrowest portion was identified at the cross-sectional diameter of the vocal cords. Unfortunately, this publication did not receive much attention and no other researchers echoed those findings up until recently. Dalal et al.,7 in a study of 128 children under 13, found that measurements of the area, cross-sectional and AP diameters at the vocal cords and the cricoid cartilage, using video bronchoscopy in anesthetized patients with controlled breathing, confirmed Litman's report.5 Although the approaches are different, the glottis is identified as the narrowest portion and the larynx as being more cylindrical than tapered. Litman observes that, although his results show that the narrowest portion of the pediatric airway is at the glottis entrance, functionally the cricoid cartilage is a rigid structure that cannot be distended, and it is the site of the greatest risk for injury.8 Another finding is that the opening of the cricoid cartilage is elliptical, with a greater AP diameter. This has implications for the way in which the ETT fits, with a higher risk for compression and lateral wall ischemia.5,7

Consequently, it is of the utmost importance to have a clear idea about the anatomy and conformation of the pediatric larynx. Diagnostic imaging techniques have shown to be a valuable tool for determining those characteristics and designing safer devices for managing the airway in children.

Has the time come to use cuffed tubes in the pediatric population?Until the end of the 1980s, based on studies of the pediatric airway, most authors recommended the use of uncuffed ETT in children under 8 years of age,9 using as an argument the possibility of using larger diameter tubes that would create less resistance to the passage of air. However, recent publications suggest that the use of cuffed ETT is safe in this age group.10

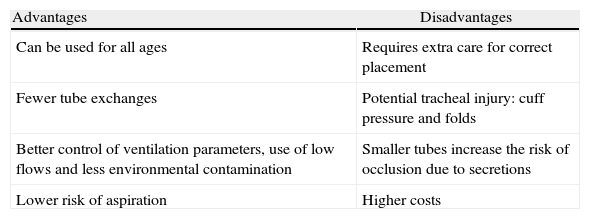

Today, cuffed tubes are low pressure/high volume tubes, and their advantages include low gas flow, less contamination, lower risk of aspiration, better control of ventilator parameters, and a lower number of intubations11,12 (Table 1).Weiss et al., in a study of 2200 of children under 5, reported a lower number of ETT exchanges when cuffed tubes were used, as compared with uncuffed tubes (2.1% vs. 30.8%), and less trauma to the airway.14

Advantages and disadvantages of cuffed tubes.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Can be used for all ages | Requires extra care for correct placement |

| Fewer tube exchanges | Potential tracheal injury: cuff pressure and folds |

| Better control of ventilation parameters, use of low flows and less environmental contamination | Smaller tubes increase the risk of occlusion due to secretions |

| Lower risk of aspiration | Higher costs |

Newth et al., in a study of 860 critically ill children, reported that cuffed tubes may be used safely for long periods of time, without any short- or long-term sequelae, provided the right size is selected and balloon pressure is monitored regularly.16

Surveys have found that 25% of anesthetists use cuffed tubes in children under 8 years of age. All anesthetists surveyed, and 45% of the intensivists, reported not checking cuff pressure routinely.13,18

Cuffed tubes have found their way into pediatric anesthesia. Progress has been made in equipment standardization and optimal design. At present, there are marked differences among the different manufacturers in terms, for example, of the external diameters used for the same internal diameter and cuff design.14,15 Weiss found 15 types of tubes from four different manufacturers17 (Fig. 2).

In conclusion, although there are situations where cuffed tubes are better than uncuffed tubes, both can cause injury to the patient. Short-term intubation, adequate diameter selection, control of head mobility with the in situ tube, and frequent cuff pressure monitoring are important factors that need to be controlled in order to avoid injury. Moreover, knowledge of the pediatric anatomy derived from well-done studies will serve as a sound basis for the design and use of devices that are suitable to the anatomy of each individual child.

Conflict of interestsNone declared.

FundingNone.

Ríos Medina Á, et al. La vía aérea pediátrica: algunos conceptos para tener en cuenta en el manejo anestésico. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2012;40:199–202.