Cardiac surgery with extracorporeal circulation in obstetric patients is a separate chapter because of the physiological changes brought about by pregnancy and factors such as anesthetic management, monitoring and perfusion during the cardiopulmonary bypass that affects both the mother and the child; both experience different circumstances and have dissimilar interests. The paper discusses the anesthetic management of a patient during her 26.2 weeks of gestation with a pulmonary thromboembolism and atrial intracavitary thrombus attached to the central catheter with atrial septal defect.

La cirugía cardiaca con circulación extracorpórea en pacientes obstétricas representa un capítulo especial, debido a los cambios fisiológicos producidos por el embarazo y factores como el manejo anestésico, la monitorización y la perfusión durante el bypass cardiopulmonar que se producen sobre el binomio madre-feto, organismos en situaciones diferentes y con intereses opuestos. Describimos el manejo anestésico de una paciente de 26,2 semanas de embarazo con un tromboembolismo pulmonar y trombo auricular adherido a catéter central con comunicación interauricular.

The first case ever reported of a pregnant woman undergoing cardiac surgery with extracorporeal circulation was described by Dubourg in 1958, for a pulmonary valvotomy and closure of an atrial septal defect in a patient in her sixth month of pregnancy.1

Heart disease is the first cause of non-obstetric death during pregnancy. It occurs in 1–3% of pregnancies and represents 10–15% of maternal deaths.1,2 Congenital heart disease has become a prevalent condition in women of childbearing age and if left untreated puts the fetus at risk as well. Morbidity and mortality following heart surgery in pregnant patients is no higher than in the non-pregnant; however, they account for up to 9–30% of neonatal–fetal deaths, respectively.3,4

Cardiac surgery with extracorporeal circulation in pregnancy is a separate and distinct entity because of the physiological changes occurring in the pregnant woman and the effects of surgery, anesthesia and cardiopulmonary bypass, on both the mother and the child. Following is a case report on the topic.

Clinical caseThis is a 34-year-old woman admitted to the ER in her 26.2 week of pregnancy according to the ultrasound. The patient underwent gynecobstetric evaluation due to progressive respiratory distress that had evolved for one day, with no chest pain but was associated with oppressive frontal headache and occasional colicky hypogastric pain. Fetal movements were present. The patient had a history of migraine last mestrual period (LMP) 19-10-2010, G2 P1 V1. The ultrasound examination on 0411-2011 indicated 26 weeks of pregnancy, fetal wellbeing with 910g of body weight. Fetal monitoring was negative unsatisfactory, category I; hematology with leukocytosis and neutrophylia. No anemia was present. Glycemia, nitrogenous compounds, bilirubin, transaminases and electrolytes all normal; partial urine test contaminated, lactic dehydrogenase 577u/L, gram in urine negative, clear chest X-ray and arterial blood gasses show metabolic acidosis. The physical examination at admission showed acceptable general status with 98/66 BP, 140× HR, afebrile, SPO2 92%, and no positive findings in the physical examination.

Initial diagnosis: (1) 26 week pregnancy according to the ultrasound; (2) severe sepsis with suspicious urinary focus; (3) chorioamnionitis was ruled out.

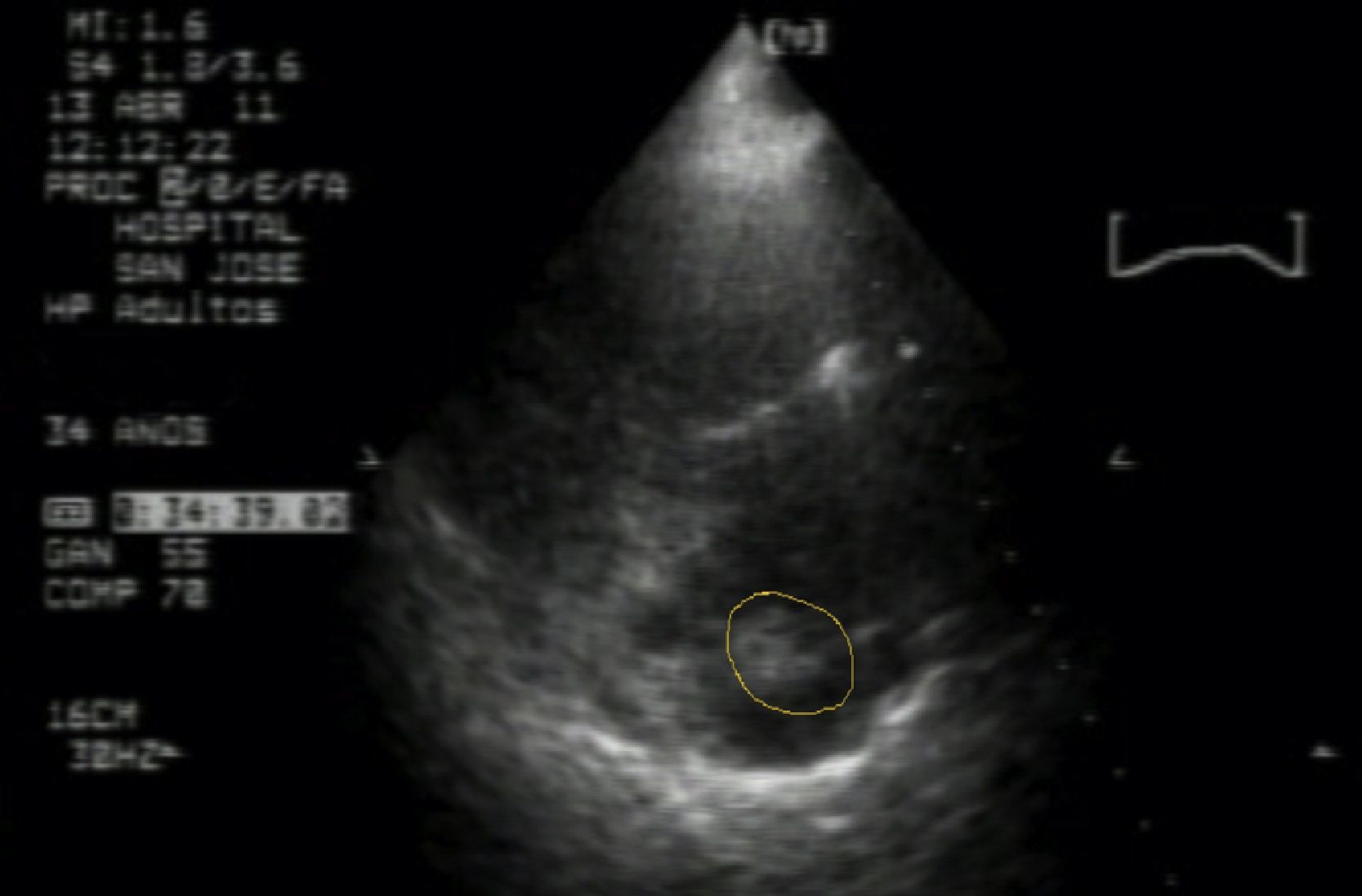

The patient was hospitalized for additional tests, including repeated uroanalysis that ruled out infection; absent bacteria in urine gram culture. There was then a suspicion of pulmonary thromboembolism and the gynecologist requested a transthoracic echocardiogram which showed a mass attached to the central catheter suggesting thrombus vs large volume vegetation, severe pulmonary hypertension PSAP 70mmHg, with dilation of right cavities and signs of pressure overload, paradoxical septal motion (Fig. 1).

The cardiologic evaluation identified a patient with a 7-day clinical presentation of constant oppressive chest pain associated with mild exertion dyspnea and palpitations due to exacerbation of symptoms, in addition to rest dyspnea. The patient denied urinary, genital or digestive symptoms, fever or chills. She mentioned a history of pregnancy with threat of miscarriage that required extended rest in the last month. No dyspnea or chest pain was identified during physical examination; HR: 100/min; BP: 120/76mmHg, HR: 18/min, T: 36°C, SAT: 94% with no need for oxygen supplementation. The positive findings included: cardiac bruits with systolic murmur III/VI with aortic predominance. Diagnostic cardiology reveals:

(1) Pulmonary cardioembolism (PCE); (2) Bilateral atrial intracavitary thrombus attached to the central catheter; (3) Infectious endocarditis?

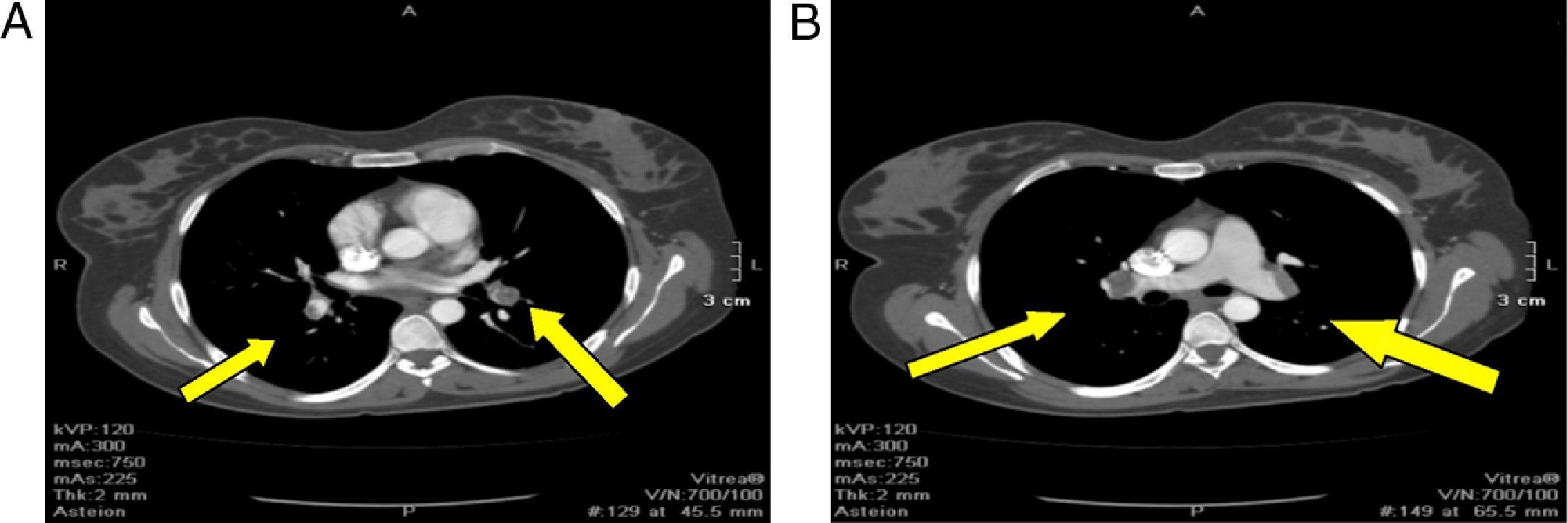

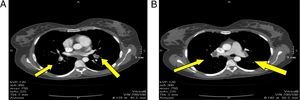

Angiotac report: positive for pulmonary thromboembolism of both pulmonary lobar and segmented arteries; anterior and posterior segment of the upper lobe, caudal extension of the thrombus into the interlobar artery partially obliterated; opacification defect on the left atrium with extension into one of the left pulmonary veins related to intracavitary thrombus; opacification defect on the right atrium probably related to an intracavitary thrombus with a diameter greater than 36mm. Important dilatation of the right cavities with septal displacement causing partial left ventricle collapse (Fig. 2)

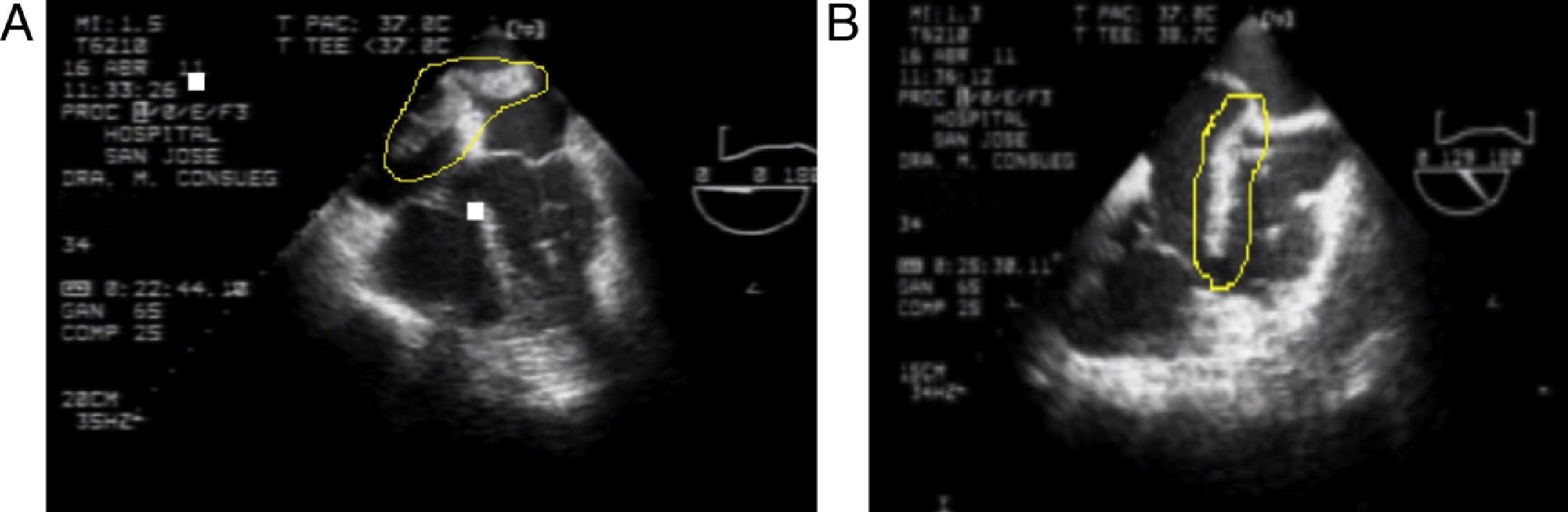

These findings confirm the PTE diagnosis and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) anticoagulation is initiated; the patient is transferred to the Intermediate Critical Care Unit (iCCU). The echocardiographic findings include: large, very mobile thrombus riding over the patent foramen ovale with high risk of embolism, severe pulmonary hypertension (SPAH) 70mmHg, moderate tricuspid regurgitation and dilatation of narrow cavities (Fig. 3).

The cardiovascular surgeon repairs the atrial septal defect and performs the pulmonary thromboendarterectomy; the procedure is performed 6 days after the patient was admitted. Invasive blood pressure monitoring, Flotrac/Vigileo continuous cardiac output monitoring and fetal monitoring were provided in the OR. Midazolam 3mg, fentanyl 500mcg, propofol 100mg and neuromuscular relaxation with rocuronium 50mg were administered for induction of anesthesia. Following orotracheal intubation the subclavian central venous catheter was placed uneventfully. Isofluorane was administered for maintenance of anesthesia during the procedure, and additional midazolam and fentanyl boluses were required. In total, 10mg of midazolam and 2.5g of fentanyl were administered until the completion of surgery. To maintain the MBP>70mmHg, phenylephrine titratable infusion was started.

Anticoagulation was controlled with an heparin dose of 400u per Kg, previously to extracorporeal circulation to maintain a minimum activated clotting time (ACT) of over 380s and an ideal over 600s. Despite increased doses of anticoagulation, the maximum clotting time was 400s.

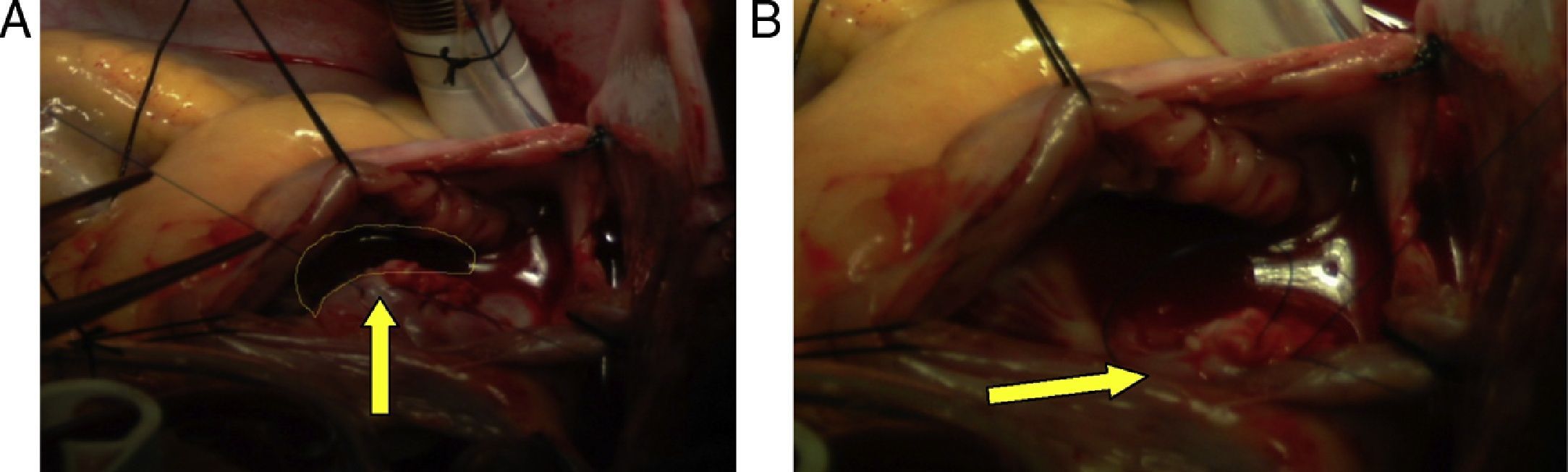

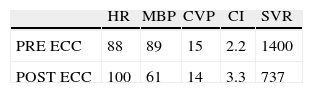

Hemodynamics (Table 1)Antegrade cardioplegia was used with an infusion of 1000cc of custodiol, the bleeding calculated was 500cc, 2units of packed red blood cells (PRBC) and 2units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) are transfused during surgery. Intraoperative findings: Approx. 6cm clot extending from the superior vena cava, right atrium and crossing over the de ASD, ostium secundum ASD of approximately 3cm in diameter, and small clots in the left pulmonary artery (Fig. 4)

Fetal monitoring prior to surgery shows a baseline of 140 and moderate variability; continuous fetal monitoring during bypass and baseline of 130 with moderate variability. During aortic clamp the fetal heart rate ranged between 180 and 60beats/min; a non-stress test (NST) monitoring was made at the end of the surgery, it was reactive.

The patient was taken to the ICU with invasive ventilatory support, phenylephrine IV infusion, BP: 104/50, HR: 97, Sat: 96%, cardiac index of 3.1, systolic volume variability 13%, CVP 12mmHg, glycemia 157mg/dl, pH 7.34, PO2 88mmHg, PO2/FiO2 ration 220, PcO2 34mmHg, HCO3 17mEq/L, BE −3mEq/L. The patient was extubated after 24h and successfully discharged.

Echocardiogram 2nd day post-op: ASD closed and satisfactory thrombectomy, Moderate Pulmonary Hypertension sPAP: 54mmHg, and discrete growth of the right cavities. Pregnancy continued to be uneventful with vaginal delivery at 36 weeks of gestation and a healthy newborn baby.

DiscussionThe management of anesthesia in a pregnant patient undergoing cardiac surgery raises multiple challenges; invasive hemodynamic monitoring is crucial because of the physiological changes during pregnancy and the baseline cardiac pathology may result in unreliable information.5 However, monitoring is an absolute requirement for surgery and to ensure fetal wellbeing, keeping in mind that the main causes of fetal bradycardia during surgery include hypotension, hypoxia, uterine contractions, decreased uterine blood flow, malposition of the mother, drugs and hypothermia.4

The use of anticlotting agents during pregnancy is specifically indicated for deep venous thrombosis, mechanical cardiac valves, recent onset atrial fibrillation, extended cardiomyopathy and during cardiopulmonary bypass. Non-fractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin do not cross the placenta and have no teratogenic effects on the fetus; thus, heparin can be safely used at the usual doses for anticoagulation, with no increased risks to the fetus.6

Cardiopulmonary bypass has deleterious effects on the uterine–placental blood flow and the fetus and these effects could be exacerbated with the activation of inflammatory processes, non-pulsatile flow, hypotension and hypothermia.7,8 If the fetus is viable, the recommendation is to monitor the uterine tone and the fetal heart rate (FHR), fetal bradycardia, sinusoidal patters and late deceleration which are indicators of fetal asphyxia that may occur at the beginning of the bypass.

The current recommendations for protecting the fetus during maternal bypass include4,7:

- (1)

Maintaining the pump flow rate at 2.5Lmin−1m−2 and the perfusion pressure>70mmHg

- (2)

Hematocrit above 28%

- (3)

Use normothermal perfusion whenever possible

- (4)

If possible, use pulsatile flow

- (5)

pH evaluation for CO2 homeostasis and control

All of the inhaled anesthetic agents and most of the IV anesthetic drugs are highly liposoluble and freely cross the utero-placental membrane. Volatile anesthetic agents also cause relaxation of the uterine tone and of the utero-placental flow (UPF). Etomidate has not shown any deleterious fetal metabolic effects or hemodynamic effects on the UPF and provides blood pressure stability.9–11 Opioids may cause fetal readycardia, respiratory distress and loss of beat-to-beat variability since they easily cross the placenta; however, due to their hemodynamic stability, opioids are excellent contributors to balanced anesthesia.12 Neuromuscular relaxants do not cross the utero-placental barrier and hence do not affect the neonatal muscle tone.13

The circulation of the pregnant woman undergoes significant changes, in addition to the impact of the cardiopulmonary bypass that induces a non-physiological hemodynamic condition that may cause adverse effects on the mother during heart surgery.14 Hemodilution, changes in coagulation, complement activation, leukocyte release of vasoactive substances, particle embolism and air from hypotension during bypass, all contribute to a deleterious effect.8

Fetal death is mainly the result of a sustained uterine contraction during surgery, but its cause is yet to be determined. Possible explanations include the dilution of progesterone resulting from extracorporeal circulation,8,15,16 hypothermia and re-warming phase that affect the pregnant uterus.17

The effects of bypass surgery on the fetus are hypoxia, hypotension, acidosis and mainly bradycardia. The mechanism is unknown but probable causes have been suggested, including fetoplacental dysfunction, maternal hypothermia and drugs that cross the placenta such B-blockers.18,19

The risk factors for maternal mortality during heart surgery include the use of vasoactive drugs, age, type of surgery, reintervention and maternal functional class.20 The risk factors for fetal mortality include mother who is aged >35 years of age, functional class, reintervention, emergency surgery, type of myocardial protection and duration of anoxia.20 However, acceptable maternal and fetal mortality rates can be accomplished through measures such as early detection of maternal preoperative cardiovascular decompensation, perioperative fetal monitoring, ECC optimization through monitoring and cardiac output optimization, in addition to programming the patient for elective surgery in the second trimester.

FundingAuthor's own resources

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Reyes O LE et al. Embolectomia pulmonar y bypass cardiopulmonar durante el embarazo. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2013;41:166–70.