Chronic renal disease is a public health problem worldwide. Several times these patients will undergo surgical procedures related to dialysis or surgeries related to their co-morbidities. The purpose of the pre-anesthesia evaluation is to assess the risk of cardiovascular events and initiate interventions that may influence morbidity and mortality. This article describes the relevant epidemiological data of chronic kidney disease and its cardiovascular risk and provides a guide on clinical assessment, diagnostic tools and strategies to reduce surgical risk. This narrative literature review is based on articles written in both English and Spanish limited to the last 10 years, information from basic textbooks and primary databases (i.e., PUBMED – EMBASE – LILACS), supported by articles referenced in the above-mentioned search.

La enfermedad renal crónica es un problema de salud pública mundial. En varias ocasiones los pacientes son llevados a cirugías relacionadas con su diálisis con operaciones propias de sus comorbilidades. El propósito de la valoración preanestésica es asesorar el riesgo de eventos cardiovasculares e iniciar las intervenciones que puedan influir en su morbimortalidad. El presente artículo describe datos epidemiológicos relevantes de la enfermedad renal crónica, así como su riesgo cardiovascular, y nos orienta en su valoración clínica, ayudas diagnósticas y estrategias para reducir el riesgo quirúrgico. La presente revisión narrativa de la literatura fue desarrollada con artículos escritos en inglés y español, limitados a los últimos 10 años, información referenciada en textos guía y bases de datos primarias (como Pubmed-Embase-Lilacs), complementada con artículos referenciados de la anterior búsqueda.

The pre-anesthesia evaluation is a comprehensive assessment of the patient's health, including the measurement of the functional organic reserves and any potential complications during the perioperative period that result in a clinical risk profile to guide the interventions that affect morbidity and mortality in the short and long term.1

The National Kidney Foundation recommends that the evaluation of patients with chronic renal disease focus on: etiological diagnosis, comorbidities, severity (level of renal function), complications and estimating the risk of renal function loss and cardiovascular complications. All these parameters of the pre-anesthesia evaluation shall be accompanied by a consideration of the surgery-related risks, in order to optimize risk factors.2

MethodologyThe methodology was non-systematic narrative literature review in both English and Spanish, limited to the last 10 years, of information published in textbooks, primary databases (i.e., PUBMED – EMBASE – LILACS) and complemented with articles referenced in the above-mentioned search. The English keywords used were: kidney disease, chronic kidney failure, perioperative care or perioperative period, mortality and anesthesia. The Spanish search included the words: Enfermedad Renal, Falla Renal Crónica, Cuiddo Perioperatorio y/o Perioperatorio. Both the search and the selection of articles was done independently by the various authors; each group read, analyzed, associated new references and prepared a draft for further analysis, validation (by the research group) and correction to render the best final version.

The search in PUBMED used the following formula and Boolean descriptors: ((((“kidney diseases”[MeSH Terms] OR (“kidney”[ALL Fields] AND “diseases”[All Fields] OR “kidney diseases”[All Fields]) AND (“perioperative care”[MeSH Terms] OR (“perioperative”[All Fields] AND “care”[All Fields]) OR “perioperative care” [All Fields])) AND (“kidney failure, chronic” [MeSH Terms] OR (“kidney”[All Fields] AND “failure”[All Fields] AND “chronic”[All Fields]) OR “chronic kidney failure”[All Fields] OR (“kidney”[All Fields] AND “failure”[All Fields] AND “chronic”[All((“mortality”[Subheading] OR “mortality”[All Fields] OR “mortality”[MeSH Terms])) AND (“anaesthesia”[All Fields] OR “anesthesia”[MeSH Terms] OR “anesthesia”[All Fields]).

Thus, eight articles were obtained of which one was included. The EMBASE search used a similar methodology but no additional articles different from those in PUBMED were identified. Three articles were found in the LILACS search, using the words (Renal Disease) AND (Perioperative care); there were no articles with (Chronic renal failure) AND (Perioperative care) and one with (Chronic Renal Failure) AND (Perioperative); none of the four articles found was included. All the articles were read and those related to the topic of interest were selected; referenced articles published in relevant books and articles were investigated and 54 references were included. In total, 55 articles were included with the general methodology. Few of the articles herein are the result of primary research, which indicates the limited research and publications on the topic; consequently, we have the responsibility for providing arguments with vital information that is not necessarily obtained from the articles and far less from indexed information with these Boolean descriptors.

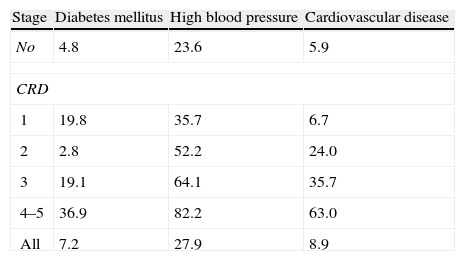

EpidemiologyChronic renal disease is a public health problem; in 2008, the incidence of chronic renal disease was 4.3% in people over 65 years of age (3.7 fold the 1995 figures) and a prevalence of 7.6% (4.6 times the 1995 figures); it was also established that the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease was higher in patients with chronic renal disease and further increased as the glomerular filtration rate decreases (see Table 1).3

Prevalence (%) diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension and cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease according to the CKD–EPI equation.

| Stage | Diabetes mellitus | High blood pressure | Cardiovascular disease |

| No | 4.8 | 23.6 | 5.9 |

| CRD | |||

| 1 | 19.8 | 35.7 | 6.7 |

| 2 | 2.8 | 52.2 | 24.0 |

| 3 | 19.1 | 64.1 | 35.7 |

| 4–5 | 36.9 | 82.2 | 63.0 |

| All | 7.2 | 27.9 | 8.9 |

Overall mortality in the US was 6.4–7.8 times above the general population and close to 5–7% of all acute renal injuries occurred during hospitalization.4 According to Nash,5 7.2% of the patients hospitalized experienced at least one episode of renal failure and of them around 20% required permanent dialysis, only 38.6% recovered fully, close to 20% died from renal failure-related causes and in the ICU this figure rose to 60%.5 In Colombia, the prevalence of chronic renal disease in dialysis rose from 44.7 patients per million inhabitants in 1993 to 573 patients per million inhabitants in 2011; the main causes being diabetes mellitus (30%), high blood pressure (30%) and glomerulonephritis (7.85%).6

Joseph7 published that the mortality of patients with chronic renal disease undergoing dialysis scheduled for surgery was approximately 4% and 47% underwent emergency procedures.

Renal function evaluationThe National Kidney Foundation and the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative define chronic renal disease as the structural or functional renal tissue damage lasting for over three months, manifested by structural or functional abnormalities, or by a drop in the glomerular filtration rate less than 60ml/kg/1.73m2.8,9 Any drop below this level represents a loss of more than 50% of the renal function in an adult and is associated with an increased risk of disease progression.

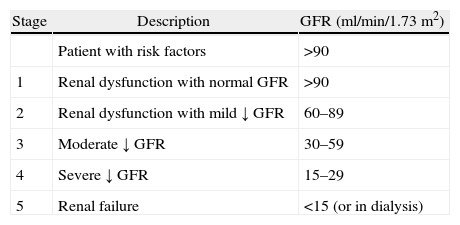

The Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) measures the ability of the kidney to filter blood and was standardized for the severity classification scheme in chronic renal disease (see Table 2).8

Chronic renal disease classification.

| Stage | Description | GFR (ml/min/1.73m2) |

| Patient with risk factors | >90 | |

| 1 | Renal dysfunction with normal GFR | >90 |

| 2 | Renal dysfunction with mild ↓ GFR | 60–89 |

| 3 | Moderate ↓ GFR | 30–59 |

| 4 | Severe ↓ GFR | 15–29 |

| 5 | Renal failure | <15 (or in dialysis) |

Serum creatinine is the most frequently used marker in clinical practice to assess renal function. However, the plasma creatinine concentration also represents the muscular metabolic function and is proportional to the muscle mass (usually higher in men and in afro-descendants). Creatinine formation decreases with age, in patients with malnutrition or muscle atrophy and in hypothermia. It is usually excreted through tubular secretion and the GI tract and increases in renal dysfunction and in the elderly; normal values of creatinine and decreased FGRs are found in elderly patients and/or with chronic disease.10

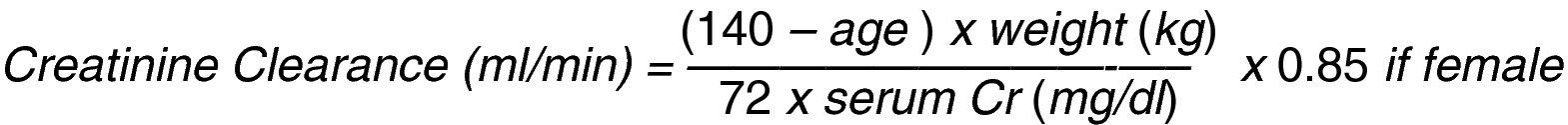

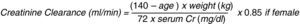

The renal function is evaluated estimating the glomerular filtration rate through creatinine clearance which represents the creatinine plasma volume that the kidney can clear in 1min and is calculated with mathematical equations; Cockroft–Gault's equation is the most widely used (Fig. 1).11

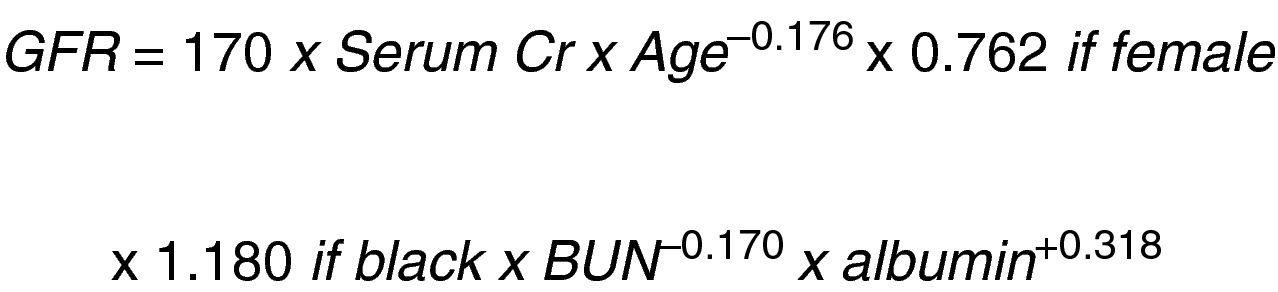

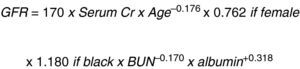

In a study on Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD), Levey et al.12 developed another equation to predict the glomerular filtration rate based on the serum creatinine concentration (Fig. 2).

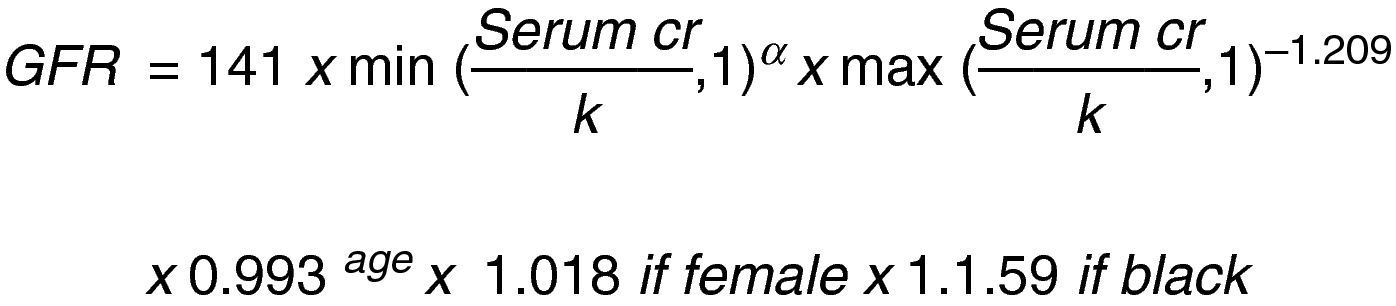

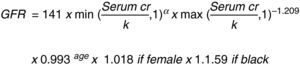

This same author then changed the MDRD equation to: “The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD_EPI)” using the serum creatinine record, age, sex and ethnicity according to the natural scale (Fig. 3).13

Let us consider this last equation as the most accurate to establish the stage of the disease and guide the evaluation of surgical risk and interventions to prevent progression.

Cardiovascular risk and chronic renal diseasePatients with chronic renal disease have a higher risk of cardiovascular complications (MI, arrhythmia, ventricular dysfunction or cardiac-related death). According to a study by Manjunath,14 per every 10ml/min/1.73m2 drop in GFR, the risk of coronary disease increases in patients between 45 and 64 years of age (OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.02–1.09).14 The HOPE (Heart Outcomes and Prevention Evaluation) trial found a higher risk of cardiovascular death in patients with serum creatinine levels between 1.4 and 2.3mg/dl, which corresponded to a prevalence of 11.4% vs. 6.6% in healthy patients; with a 1.4 risk (95% CI 1.16–1.69) regardless of treatment.15 Tatsuhiko et al. also found similar results with an OR of 13.1 for major cardiac events in patients with a glomerular filtration rate <60ml/kg/1.73m2.16

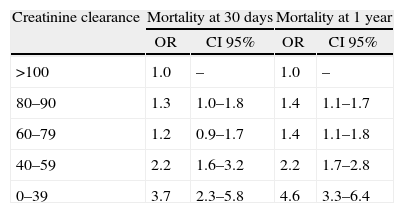

In patients undergoing surgery, a decreased renal function was associated with higher cardiac morbidity and mortality, depending on the patient's prior functional class, his/her disease stage and type of surgery. In a prospective analysis17 during the first 30 days following lower extremity revascularization, the risk of dying was increased (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.71–1.77), as well as the risk of cardiac arrest (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.09–1.88), myocardial infarction (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.39–2.16) or extended intubation (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.28–1.94) in patients with GFR between 30 and 59ml/kg/1.73m2.17 Another short term prospective analysis following heart surgery found an increased mortality with GFR between 40 and 59ml/kg/1.73m2 and was significant in patients with less than 39ml/kg/1.73m2 (Table 3).18

Mortality results at 30 days and one year of patients undergoing heart surgery based on creatinine clearance (ml/min) according to the Cockrft–Gault equation.

| Creatinine clearance | Mortality at 30 days | Mortality at 1 year | ||

| OR | CI 95% | OR | CI 95% | |

| >100 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 80–90 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.8 | 1.4 | 1.1–1.7 |

| 60–79 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.7 | 1.4 | 1.1–1.8 |

| 40–59 | 2.2 | 1.6–3.2 | 2.2 | 1.7–2.8 |

| 0–39 | 3.7 | 2.3–5.8 | 4.6 | 3.3–6.4 |

There are multiple indexes to predict cardiovascular complications during the preoperative evaluation of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery.19,20 One of the most popular is Lee's revised cardiac risk index; these data come from a prospective study in 2893 patients and were validated in 1492 patients and identified renal disease (creatinine>2mg/dl) as an independent risk factor for perioperative cardiovascular complications (acute MI, CVAs, heart failure and death).21–23

Clinical evaluation and diagnostic toolsEmergency surgery in patients with chronic renal failure is associated with higher morbidity and mortality and is not deferrable; in contrast, programmed surgery may be delayed until the renal function is optimized in the presence of acute injury and its resolution may be even accelerated if treated concomitantly with the triggering event.24

Whichever the type of surgery (emergency or programmed), the clinical history must be carefully recorded. In the ER, the clinical and paraclinical evaluation is limited to simple clinical data (i.e., vital signs, general aspect, signs of hypervolemia) and simple paraclinical data such as blood test, electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, chlorine, and phosphorus), uroanalysis, serum creatinine and electrocardiogram.1

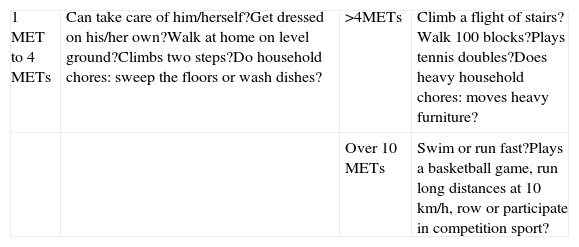

The clinical record shall address active cardiac conditions (active or recent acute myocardial infarction, decompensated heart failure, severe valve disease and complicated arrhythmias).1 The functional capacity should be established, expressed in metabolic equivalents (METs), according to the classification of the American Heart Society (AHA) (Table 4)18,25; patients with a functional capacity <4 METs usually require additional studies to assess the cardiovascular risk.

Estimated energy requirements for various activities in METs.

| 1 MET to 4 METs | Can take care of him/herself?Get dressed on his/her own?Walk at home on level ground?Climbs two steps?Do household chores: sweep the floors or wash dishes? | >4METs | Climb a flight of stairs?Walk 100 blocks?Plays tennis doubles?Does heavy household chores: moves heavy furniture? |

| Over 10 METs | Swim or run fast?Plays a basketball game, run long distances at 10km/h, row or participate in competition sport? |

Based on the principle of evaluation of the severity of the renal pathology and the intensity of the surgery programmed,9 the following has been suggested: patients with chronic renal disease, stages 1–2 and functional capacity >4 METs undergoing low or intermediate risk surgery, need no additional studies. Stage 3, 4 or 5 chronic renal patients or patients undergoing high risk surgery should include an electrocardiogram, blood test, chest X-ray, glycaemia, urea nitrogen, creatinine, albumin and electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, chlorine and calcium (if relevant to treatment) in their initial evaluation. Similarly, in patients with renal replacement therapy undergoing high or intermediate risk surgery, the recommendation is to monitor electrolytes and clotting times after 2h of the last dialysis session to optimize the perioperative requirements.26

In chronic end-stage renal disease, the ECG may show unspecific changes such as ventricular hypertrophy, electrolytic disorders and uremic pericarditis, all of which made the evaluation of the coronary disease more difficult. In patients with chronic end-stage renal disease, Foley27 found with echography that 15% had systolic dysfunction, 32% ventricular dilatation and 74% ventricular hypertrophy, each clearly correlated to coronary disease, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia or hypoalbuminemia.27

According to the AHA perioperative evaluation guidelines, doing a non-invasive stress test is a II-B recommendation for patients with one or more risk factors and a functional capacity <4 METs. In the case of Dipyridamole scan in patients with chronic end-stage renal disease, multiple specificities and sensitivities have been reported and hence its diagnostic value is limited; however, when combined with Thallium scan its diagnostic performance improves, showing a negative predictive value of 98%.28 The dobutamine stress echocardiography shows higher sensitivity and specificity and seems to approach the diagnosis of coronary disease in patients with chronic renal disease. In studies of patients who are candidates for renal transplantation, the specificity was 71–95% and the sensitivity 37–95%.29–31 The diagnostic performance of the myocardial perfusion for coronary disease in patients with chronic end-stage renal disease is variable, with specificities between 37 and 90% and sensitivities between 40 and 90%.32

Strategies for reducing surgical riskThe success in the prevention of complications during the perioperative period includes the identification and optimization of patients at risk, a proper anesthesia plan, renal function monitoring and timely interventions.

Euvolemia, adequate hydration that ensures adequate perfusion and cardiac output, are still the key strategies for renal protection in this population.33–35

It is important to avoid the use of nephrotoxic agents during the perioperative period (Ex., aminoglycosides, amphotericin B, Acyclovir, Cyclosporine, Tracolimus, Cysplatinum, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and contrast media).36,37

Contrast media induced nephropathy occurs in 15% of patients with chronic renal disease; 12% of these patients require hemodialysis and long hospitalizations. Thus preventive interventions such as controlled hydration and urine alkalinization become important.38 A study with 502 patients compared the administration of sodium bicarbonate in Dextrose versus 0.9% saline infusion prior to the contrast exposure in patients with a glomerular filtration rate <60ml/kg/1.73m2 and oral prophylaxis with N-acetylcystein; no significant differences were identified between the two groups and despite the interventions, around 10.8% presented nephropathy.39

The risk of perioperative hemorrhage may be increased in patients with chronic renal disease because uremia causes platelet dysfunction. The recommendation is that the patient should be uremia free and the last dialysis should be performed the day before.40 Other strategies to prevent perioperative bleeding use hemostatic agents; desmopressin may shorten the bleeding time but the prior use of recombinant erythropoietin41 has limited its field of action. Dual ASA (Acetyl Salicylic Acid) and Clopidrogel therapy increase the risk of bleeding up to 1% vs. ASA alone42; depending on the risk of hemostatic involvement during surgery, it is recommended that Clopidrogel is removed five days before and assess ASA continuity on the basis of risk vs. benefit of bleeding.43

The renal–vascular effects modulated with renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors may be potentiated under general anesthesia, increasing the risk of loosing systemic blood pressure and renal vascular tone control.44 In a prospective study of 249 patients undergoing elective aortic surgery, a 20% decrease of the glomerular filtration rate was identified seven days after surgery, in patients under chronic treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors.45 Hence, the recommendation is to stop these agents, including the angiotensin receptor agonists, at least ten days prior to the procedure and start them after surgery, only in euvolemic state with no evidence of acute renal injury.46

In contrast to Dopamine, the administration of Fenodopam has shown to reduce mortality and the incidence of renal replacement therapy, although hard data are missing to confirm this fact independently.47 The use of diuretics and osmotics such as mannitol has no preoperative support, and their indication is more important during surgery.

Numerous studies have shown the effect of statins on perioperative morbidity and mortality48 based on their pleiotropic effect.49,50 The “StaRRS: Statins for Risk Reduction in surgery” trial found a protective effect from cardiovascular complications in the sub-group of peripheral vascular surgery (OR 0.52).51

One of the preventable complications in patients with chronic renal disease in the perioperative is cardiac arrhythmias and myocardial depression secondary to hyperkalemia. In case of emergency surgery, the recommendation is to administer calcium gluconate and dextrose infusion with crystalline infusion, in addition to sodium bicarbonate and micronebulizations with salbutamol associated with the specific management of arrhythmia.52–54

Finally, in the patient with chronic end-stage renal disease undergoing elective surgery, the recommendation is to do renal replacement therapy the day before the procedure and follow a strict diet control.55

ConclusionsChronic renal disease is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular complications and perioperative death and represents a cornerstone in the pre-anesthetic evaluation. Proper diagnosis and staging of the risk of acute postoperative dysfunctions helps in clearly defining the renal protection measures, as well as in identifying any associated risk factors that lead to the correct prescription of additional studies and treatments.

FundingNone

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare not to have any conflicts of interest.

To our families (parents, wives and children).

Please cite this article as: González Cárdenas VH, et al. Valoración preanestésica en el paciente con enfermedad renal crónica (énfasis en riesgo cardiovascular). Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2013;41:139–45.