Spasticity is triggered by a central nervous system disorder and may be local or generalized. The severity of symptoms, including functional limitation, deformity, pain, sleep disorders, depression and multiple disabilities, depends on the areas involved. The treatment of the disease is based on physical therapy and complemented with posture correcting devices, a few surgical interventions and drug therapy. Baclofen is a useful drug for this pathology and is usually administered orally; however, due to its low bioavailability or poor tolerance some patients require intrathecal administration.

ObjectiveThe purpose of this article is to present a literature review based on a case report of a patient with a diagnosis of spastic tetraparesis, receiving intrathecal baclofen treatment through an implantable intrathecal therapy pump (ITP).

Methods and materialsA database search was conducted in EBSCO, MEDLINE and OVID that included systematic review articles, clinical trials, narrative reviews and case series between 1995 and 2012, for a non-systematic narrative review and a case report.

Results35 articles were considered in total for an update on the topic suggested.

ConclusionsBaclofen use through an implanted ITP is an effective and safe option for treating patients with severe spasticity refractory to conventional oral therapy.

La espasticidad es desencadenada por una alteración en el sistema nervioso central; puede presentarse de manera local o generalizada. La severidad de los síntomas —entre ellos, limitación funcional, deformidad, dolor, trastorno del sueño, depresión y múltiples incapacidades— depende de las zonas comprometidas. El tratamiento de la enfermedad se basa en la terapia física y es complementado con correctores de postura, algunas intervenciones quirúrgicas y terapia farmacológica. El baclofeno es un medicamento útil en esta patología. La vía de administración inicial siempre es oral, sin embargo por su baja biodisponibilidad o mala tolerancia en algunos pacientes se requiere la vía intratecal.

ObjetivoEl objetivo del presente artículo es presentar una revisión de la literatura aprovechando el reporte de un caso de una paciente con diagnóstico de tetraparesia espástica que recibió tratamiento con baclofeno intratecal mediante la implantación de una bomba de terapia intratecal (BTI).

Métodos y materialesSe realizó una búsqueda en las bases de datos EBSCO, MEDLINE y OVID, que incluyó artículos de revisiones sistemáticas, ensayos clínicos, revisiones narrativas y series de casos, entre 1995 y 2012, para la realización de una revisión narrativa no sistemática y reporte de un caso.

ResultadosSe tuvieron en cuenta un total de 35 artículos para la realización de la actualización en el tema propuesto.

ConclusionesEl uso del baclofeno mediante la implantación de BTI es una alternativa efi-caz y segura para el tratamiento de los pacientes con espasticidad severa y refractaria al tratamiento oral convencional.

Spasticity is defined as a motor disorder characterized by a velocity-dependent increased muscle tone, with exaggerated stretching reflexes, as a component of the upper motor neuron syndrome.1 In the United States spasticity is present in half of the patients with multiple sclerosis, cerebral paralysis, cerebrovascular accident, head trauma and marrow injury. Severe spasticity may be associated with major functional limitation, deformity, pain, depressive symptoms, sleep disorders, impaired quality of life and extended disability.2

It maybe a characteristic of a disorder that affects the corticospinal tract, which may occur in several central nervous system pathologies. It may be focal or generalized, depending on the localization and extension of the neurological injury involved. Such an extension will determine the level of functional limitation and the intensity of pain will depend on the severity of the spasticity.3

The diagnosis is clinical, based on rating scales such as “Ashworth” (0: no increased tone, 1: mild increased tone, 2: major muscle tone increase, but the limb may be easily flexed, 3: increased muscle tone, difficulty for passive mobilization, 4: total limb stiffness in flexion or extension); “Penn” (0: no spasm; 1: mild spasm with stimulation, 2: strong irregular spasms, less than one per hour, 3: more than one spasm per hour, 4: more than 10 spasms per hour); or “Tardieu”4 and functional tests like for instance the functional independence measurement for children known as “WeeFIM”.5 However, the underlying cause should be identified. Treatment implies improving the functional activity, the mobility and relieving pain. This is accomplished through physical therapy, use of posture corrective devices, surgical procedures and drug therapy.6

Baclofen is the most popular drug used for the treatment of spasticity. It is an FDA-approved gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor agonist in the spinal cord. It decreases the release of excitatory neurotransmitters with the subsequent decrease of bone marrow reflexes. Baclofen controls spasticity in 70–87% of the patients and decreases the frequency of spasm during the day. The route of administration of choice is the oral route; however, its bioavailability is low and thus the response in some patients is low or poorly tolerated, and requires an intrathecal approach to achieve a concentration in the effector site 100-fold than with the oral administration. Intrathecal baclofen has a 6-h half-life so administration must be continuous. Consequently, intrathecal therapy pumps are used.7

The purpose of this article is to present a literature review using a case report of a patient diagnosed with spastic tetraparesis and who received intrathecal baclofen therapy with an implanted ITP.

Clinical caseIt was a case of a 37-year old patient with a 22-year history of left side spasticity of unknown etiology. It began in the left foot, with gate disorders and multiple falls, with ascending progression to the knee. The spasticity was reactivated in the last six years, compromising the upper left limb (elbow and hand) and the temporomandibular joint.

Multiple specialists, including neurology, neurosurgery, neuropsychology, a neurology medical board, an abnormal movements medical board and finally, a pain medical board, assessed the patient.

Multiple laboratory tests were performed, including cerebrospinal fluid cytochemistry, simple and contrast spinal MRI, head MRI, vitamin B12 and folic acid serum levels, VDRL, antinuclear antibodies, and HIV, HTLV-1. All were normal. A clear cause for the spasticity could never be identified and hence the treatment administered was addressed to control stiffness, reduce the frequency of the spasms and control pain.

The patient received multiple treatments with valproic acid, duloxetine, gabapentin, tizanidine, botulin toxin, clonazepam, pregabalin, tramadol, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and oral baclofen at initial doses of 10mg every 12h with weekly 10mg increases up to a dose of 80mg per day but the symptoms could not be controlled.

During the last six months of the disease, the patient experienced overt deterioration with involvement of the four limbs that prevented ambulation and required wheel chair; later the patient became bed-ridden because the severity of the spasticity prevented her from sitting down on the chair. There were sphincter control loss, worsening of depressive symptoms and increased pain intensity. Spasticity was the cause for functional limitation and pain. The patient was admitted to a fourth level institution where the pain medical board evaluated her and intrathecal baclofen treatment was suggested.

The protocol used began with the administration of test-doses. The first dose received was of 50μg of intrathecal baclofen and it provided a 2-point improvement in the Ashworth scale, mainly in the hands and the right lower limb (Fig. 1). The second dose was administered 24h later. This dose was of 75μg and achieved a four point improvement in the Ashworth scale on both right limbs, three points in the upper left limb and 2 points in the lower left limb. It was even possible to make the patient sit up after being bed-ridden for three months (Fig. 2). She also recovered sphincter control. Both test doses were administered in the right lateral decubitus position, at the level of L3L4, which was technically challenging because of the patient's characteristics. No adverse effects were seen.

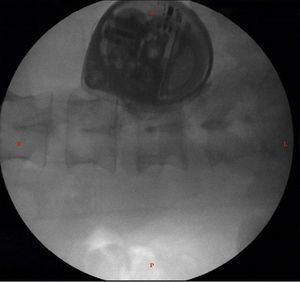

There was no need for further testing and the definite insertion of the ITP was programmed, under general anesthesia and in a left lateral decubitus position. A L3L4 approach was used under fluoroscopy guidance; cerebrospinal fluid return was identified, the intrathecal catheter was advanced up to T1T2, where it was definitely attached. The catheter was then tunneled from the lumbar region to the right paraumbilical abdominal region where the pocket was formed for the final implant of the pump (Fig. 3).

The pump was implanted/Synchromed II Medtronic®) and filled with one 10mg blister of baclofen in 20mL (Lioresal®, Novartis Pharma) and was programmed in a continuous simple mode to administer the drug at a rate of 50μg per day.

This was an outpatient procedure that lasted 90min with a 2-h recovery. Oral baclofen was removed and the rest of the drugs were maintained at the same dose. An evaluation was performed after 24h when the patient already showed partial symptom improvement. A second evaluation was done at 72h when the patient walked in the office, with considerable improvement of spasticity, decreased frequency of spasms (one point in Peen's scale) and reduced pain intensity. Intensive physical therapy was initiated for the first four weeks. Weekly evaluations followed for one month and then every three months for one year (Fig. 4).

The baclofen doses were stable, requiring only an increase from 50μg to 60μg in the first month, and from 60μg to 75μg in month six.

The only adverse event observed was increased spasticity in the sixth month, secondary to a urinary infection that required changing the dose in addition to antibiotic therapy for 10 days. Then the patient recovered her functional condition.

With regards to analgesia, oxycodone was removed and switched to hydrocodone. Pregabalin was maintained at 75mg every 8h.

Sleep quality improved and hence clonazepam was removed.

Quality of life improved to the extent that the patient was able to go back to college to continue her career.

DiscussionSpasticity is a motor disorder characterized by increased passive muscle resistance to stretching, followed by increased muscle tone that depends on the stretching velocity. Spasticity is accompanied by hyperreflexia and a variable degree of muscle weakness. Muscle tone is controlled by the descending motor pathways. It is the result of a balance between facilitating pathways of the extensor tone, mediated by the medial reticulospinal and medial vestibulospinal tract and by inhibitory effects mediated by the dorsal reticulospinal tract. When the latter is impaired, spasticity occurs. Additionally, there are changes in the makeup of the central nervous system that account for other clinical findings.8

There are multiple oral therapies available for managing spasticity9:

Dantrolene: acts directly on the skeletal muscle blocking the contraction by inhibiting calcium release of the endoplasmic reticulum; the downside is the potential to trigger serious hepatotoxicity.10 The starting dose is 25–50mg per day and increases to 25mg every four days up to a maximum dose of 400mg per day. This drug is not available in Colombia.

Ciproheptadine: inhibits the release of acetylcholine, histamine and mainly serotonin, in various sites of the central nervous system. The starting dose is 4mg and increases every five days up to a maximum dose of 16mg per day. It may be used to treat baclofen withdrawal syndrome.11

Benzodiazepines: the most widely used is diazepam. These agents act on the GABAA receptor, increasing the calcium flow to the neuron, hyperpolarizing the neuron and inhibiting the afferent motor activity. Due to its adverse effects, mainly somnolence, these agents are not considered as a first line therapy. Clonazepam has also been used to treat nocturnal spasms.12

Cannabinoids: these agents act on the Cb1 and CB2 receptors, in addition to the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Dronabinol and nabilone have been used in multiple sclerosis patients. The starting dose for dronabinol is 2.5–5mg per day, with every five-days increase up to a maximum dose of 20mg.13,14

Glycine: this is one of the most abundant inhibitory amino acids in the spinal cord. Threonine at a dose between 6g and 7.5g per day has shown to reduce the muscle tone in patients with multiple sclerosis and cord injuries.

Alpha-2 adrenergic drugs: clonidine has been shown to inhibit the release of glutamate and decrease the spasticity through the presynaptic inhibition of alpha-2 receptors in the afferent pathways.

Tizanidine: inhibits the release of excitatory neurotransmitters and facilitates the glycine action. Its efficacy has been proven in patients with multiple sclerosis, stroke, spinal cord injury and head trauma.15

4-Aminopyridine: inhibits the potassium channels in demyelinated areas in patients with multiple sclerosis and improves the central and spinal cortical activity in patients with spinal injury. It may result in thrombocytopenia, seizures, arterial distal vasospasm, liver failure, nausea and dizziness.

Other therapies: other drugs have been used to reduce spasms with variable results: piracetam, prograbide and ivermectine. Randomized clinical trials have shown benefit with gabapentin at doses between 1200 and 2700mg per day.16

This particular patient had received tizanidine, gabapentin, diazepam, with partial effectiveness. Last year she received clonazepam due to increased nocturnal spasms. Finally, a regimen of oral baclofen at a maximum dose of 80mg per day was started with poor response.

In addition to spasticity treatment, chronic pain control must be given. Pain in spastic patients is treated with baseline physical therapy and a rage of pharmacological options, selected on the basis of the triggering pathology, the severity and the number of limbs affected. When spasticity is focal botulin toxin injections tend to be effective, particularly in patients with a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis or in spasticity following cerebrovascular disease.17,18 Peripheral nerve block has also been used for focal spasticity with neurolytic substances such as alcohol19 or phenol at lower concentrations below 5%, to prevent a definitive nerve damage, with improvements for 3–6 months periods.20 These blocks are more successful and safer if guided with electromyography or ultrasonography.21,22

If the involvement is generalized, systemic therapies are recommended, including again benzodiazepines (diazepam, clonazepam) with additional effects such as sedation, somnolence and risk of addiction; alpha 2-agonists (clonidine, tizanidine) with the potential for hypotension, somnolence and constipation. Cannabinoids have proven to be effective as well as antispasmodic and analgesic agents, but with multiple adverse effects.23 There have been some reports as well on the use of phenol at neurolytic concentrations for nerve blocks. Strong opioids may be used for treating severe pain.24

The most widely used drug in spastic patients is baclofen. It is indicated for patients with multiple sclerosis, head trauma, spinal injury and dystonia.25 Its use has been widely reported in children for posttraumatic neurological disorders and cerebral palsy.26,27

Baclofen has low liposolubility, which reduces its bioavailability when administered orally and has a limited ability to cross the blood brain barrier. Its half-life with single intrathecal doses is short and hence it requires continuous administration through an in-dwelling catheter in the spinal subarachnoid space, connected to a continuous infusion pump implanted in the abdomen and with external software control.28

Oral baclofen is effective in 55–96% of the patients. The incidence of adverse effects is around 10–75%. The most usual side effects are somnolence, excessive weakness, vertigo, psychological alterations, headache, nausea, vomiting, asthenia, depression, diarrhea and hypotension. The main risk with the oral treatment is the withdrawal syndrome that causes seizures, psychiatric disorders and hyperthermia. In severe cases it may even cause rhabdomyolysis and even death.29 The major adverse effect referred by the patient was somnolence and psychological alterations. Due to its clinical inefficacy, treatment was started using the intrathecal approach.

Intrathecal baclofen acts through the GABAB receptors in the spinal cord; it was approved in the United States for subarachnoid use in patients with spinal cord spasticity in 1992 and for cerebral spasticity in 1996. It is indicated for patients unresponsive to oral baclofen therapy or patients with intolerable side effects.

A systematic review published in the Cochrane database supports the effectiveness of intrathecal baclofen in patients with spasticity and poor therapeutic response to tizanidine.30

ITPs have been used for over 20 years for the continuous administration of intrathecal drugs. These pumps allow for a continuous dosing of drugs for the treatment of spasticity, chronic benign pain and cancer pain.31

Intrathecal baclofen is indicated for patients with a positive response to the test doses. In this particular patient, only two tests were completed because of the significant improvement is spasticity. The usual test dose is around 25–100μg in adults and 10–50μg in children, administered as a single dose or in continuous infusion via a lumbar puncture. The continuous infusion test requires placing an intrathecal catheter and an external pump in order to change the dose more accurately; it can be left up to approximately seven days, during which the dose may be changed and its effectiveness checked.

ITPs shall be implanted in the OR under total asepsis. The pump is placed in the subcutaneous tissue over the abdominal wall in adults and in the subfascia in children, with the patient in lateral decubitus. Fluoroscopy may help to monitor the exact placement of the catheter tip, which varies in accordance with the anatomical site involved. In patients with tetraparesis, the tip of the catheter shall be placed in the cervicothoracic region, as it was the case with this patient.

Baclofen infusion may be administered in bolus, as a continuous infusion or a combination of both. The follow-up must be at regular intervals to be able to establish the proper dose, in accordance with the clinical evaluation using the spasticity scales. The recharge frequency is determined by the dose and the drug concentration; the average is once in every three months, and the maximum is at every six months.

The complications with the pump implantation are more frequent in children; that is, the development of seromas, hematomas, infection, pump or catheter breakage, catheter migration or fracture and the formation of pseudomeningocele. Any pump failures or delays in recharging may result in withdrawal syndrome and cause potentially dangerous symptoms such as respiratory distress, rhabdomyolysis, hypertension or hypotension and coagulation disorders. Granulomas in the tip of the catheter may develop, and these are more frequent with other drugs.32,33 A retrospective study in 126 patients with baclofen intrathecal therapy, observed a prevalence of delirium in 9.5% of the sample; of this 9.5%, delirium was secondary to intoxication in 66.6% and withdrawal in 33.3%. None of the patients died from adverse neurological effects.34 In a follow-up of one year, the patient did not experience any neurological complications.

Baclofen tolerance is observed in 15–20% of the patients during the first 12 months after implantation of the ITP. Heetla et al., completed a 10-year follow-up in 37 patients with intrathecal therapy. All required an increase in the dose of baclofen during the first 18 months and continued with an average dose of 350μg per day. 22% of the patients developed tolerance defined as a dose increase over 100μg per year.35 Our patient began with a 50μg dose for four weeks, at the end of which required an increase to 60μg and this dose was maintained for six months; then it was raised to 75μg and remained with that stable dose for one year.

ConclusionsThe use of baclofen via an implanted intrathecal therapy pump is an effective and safe alternative for the treatment of patients with severe spasticity, refractory to conventional oral therapy, with significant quality of life improvement.

FundingThis review was funded with the author's resources and with the advise of the CES University, Medellín, Colombia.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rivera Díaz RC, et al. Baclofeno intratecal para el tratamiento de la espasticidad. Reporte de caso con revisión temática. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rca.2013.03.004.