Sedation is defined as the set of actions aimed at having a quiet, comfortable, pain-free patient during a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure without any bad memories. Since the standard regional anesthesia techniques used in clinical practice are relatively traumatic and painful procedures, sedation has been introduced to make these interventions more comfortable for the patient and to facilitate the patient's cooperation.

ObjectiveTo establish the efficacy of three sedation guidelines in patients undergoing subarachnoid anesthesia.

MethodologyExperimental, randomized, prospective, single blind clinical trial comparing three guidelines for the sedation of patients undergoing subarachnoid anesthesia.

ResultsAll of the patients in the trial received anxiolysis, collaborated with the puncture and said that they would not be afraid to receive subarachnoid anesthesia in the future. There were no complications including respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting or any other complications reported with the use of the sedation guidelines. Patient satisfaction was high. Withdrawal reflex (P=0.0003) and puncture related pain (P=0.0069) were more common in the group using the intravenous midazolam-only guideline and patient satisfaction with sedation was also lower in this group; however, the three guidelines showed good efficacy.

ConclusionsThe three sedation guidelines presented were effectively used in subarachnoid anesthesia; the results were more favorable with the use of midazolam+fentanyl or midazolam+ketamine.

p-2011-1682 Colciencias. Registro # NCT0213664 (clinicaltrials.gov,prospectivo).

la sedación es un conjunto de acciones dirigidas a lograr que un paciente se encuentre tranquilo, cómodo, libre de dolor o de malos recuerdos mientras se realiza un procedimiento diagnóstico o terapéutico. Dado que las técnicas anestésicas regionales empleadas en la práctica clínica habitual son procedimientos relativamente traumáticos y dolorosos, se han asociado a sedación, para hacer este tipo de intervenciones más confortables para el paciente y hacer más fácil la colaboración del mismo.

Objetivodeterminar la eficacia de tres pautas de sedación en pacientes que van a ser sometidos a anestesia subaracnoidea.

MetodologíaEstudio experimental, ensayo clínico, aleatorizado, prospectivo, simple ciego, en el cual se compararon tres pautas para sedación en pacientes sometidos a anestesia subaracnoidea.

Resultadostodos los pacientes del estudio tuvieron ansiolisis, colaboraron a la punción y refirieron que volverían a recibir una anestesia subaracnoidea sin temor, además no se reportaron complicaciones tales como depresión respiratoria, náuseas, vómitos u otra, con las pautas de sedación utilizadas, siendo alta la satisfacción por parte de los pacientes. El reflejo de retirada (P=0,0003) y el dolor a la punción (P=0,0069) se presentaron en mayor proporción en el grupo que usó como pauta solo midazolam intravenoso, en este mismo grupo hubo menor satisfacción con la sedación; sin embargo, las tres pautas mostraron una buena eficacia.

ConclusionesLas tres pautas de sedación propuestas fueron eficaces para su uso en anestesia subaracnoidea, con mejores resultados cuando se usó midazolam más fentanilo o midazolam más ketamina.

p-2011-1682 Colciencias. Registro # NCT0213664 (clinicaltrials.gov,prospectivo).

Sedation is a set of actions aimed at having a quiet, comfortable, pain-free patient during a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure without any bad memories.1 Considering that the standard regional anesthetic techniques used in clinical practice are relatively traumatic and painful procedures,2 they have been frequently associated with sedation to make these interventions more comfortable for the patient and to facilitate patient cooperation.3,4 Not every anesthesiologist uses or indicates sedation in the same manner, but most anesthesiologists use sedation. Some administer sedation systematically before or after the puncture for a regional block, or when multiple punctures are required, while others administer sedation only if the patient is anxious.5

There are various drugs available for sedation in anesthesiology with a range of anxiolytic, amnesic and even analgesic properties, including barbiturates, benzodiazepines, opioid analgesics, and combinations thereof. Some examples are ketamine, midazolam, fentanyl, propofol, dexmedetomidine, inter alia.6,7 There is a genuine need to implement sedation techniques that are effective, safe, hemodynamically stable and with few side effects such as respiratory or cardiovascular depression, nausea and vomiting, in addition to low-cost to provide anxiolysis, analgesia or somnolence in patients undergoing procedures such as subarachnoid anesthesia.6 Hence sedation in an aware patient – when the patient responds normally to verbal stimuli, has a preserved cognitive function and coordination, unaltered ventilation or cardiovascular function – is a valuable tool.8–12 The ideal sedation state depends on the type of patient, the type of procedure and the drugs used. However, the recommended level of sedation is 2–3 or conscious sedation, in accordance with the Ramsay scale for improved wellbeing and collaboration, and no intervention required to maintain the airway, preserving adequate spontaneous ventilation and normal cardiovascular function.1,13,14

The objective is to establish the efficacy of the three sedation guidelines in patients undergoing subarachnoid anesthesia.

Materials and methodsAn experimental, randomized, prospective, single blind clinical trial comparing three guidelines for the sedation of patients undergoing subarachnoid anesthesia was undertaken at the Caribe University Hospital in Colombia.

The patients were divided into three groups: Group 1 received midazolam 0.03mg/kg; Group 2 received midazolam 0.015mg/kg+fentanyl 0.8mcg/kg; and Group 3 received midazolam 0.015mg/kg+ketamine 0.25mg/kg. In every case the patients received a single dose with no further infusions, in accordance with the recommendations on the use and dosing of each sedation drug. The O.R. anesthesiologist prepared, administered and controlled the sedation and its effects.

The size of the sample was estimated with a 95% confidence interval, 80% power and an 80% estimated percentage improvement in the experimental group,6,15 for a total of 75 patients and were randomly assigned to one of the three groups, with 25 patients per group. All the patients selected met the inclusion criteria: age 18–60 years old, scheduled for elective surgery, having a pre-anesthesia evaluation, BMI between 18.5 and 29.99kg/m2, not being pregnant, fasting for more than 8h the day of the procedure, require subarachnoid regional anesthesia with no contraindications, being able to administer the anesthesia with the patient in lateral decubitus, no identified history of allergies, having signed the informed consent for voluntary participation, and not having an ASA>II classification as an exclusion criteria, or having spinal malformations that hinder a subarachnoid block with no major difficulties.

ProcedureThe patients were randomized to one of the three sedation guidelines using a random number generator,16 with a minimum value of 1 and a maximum of 3. As patients were selected, the corresponding guideline was followed in sequential order. The patient was admitted to the OR with an 18-20G peripheral venous catheter in place, and monitored with electrocardiogram (ECG), non-invasive arterial blood pressure (NIABP), and pulse oximetry oxygen saturation (SpO2). The hemodynamic variables were recorded at admission to the OR using a vital signs monitor. One of the sedation guidelines previously established was administered to the patient according to the patient's body weight, and 1L/min oxygen therapy was administered though a nasal cannula. The hemodynamic changes were recorded 2.5 and 5min following the administration of the guideline and the Ramsay scale was used at those time points. The patient was positioned for the anesthetic technique and the subarachnoid anesthesia was administered using a Quincke 26 Gauge needle by the experienced team of anesthesiologists that authored this trial. The number of attempts and the difficulty to administer the block was recorded. At the end of the procedure a survey was administered to measure the patient's satisfaction with the subarachnoid block.

The data were collected using a form that included the socio-demographic characteristics, and target variables. Two measurement scales were used:

The first one was the Ramsay scale, which is used to evaluate the depth of the sedation. This scale has been validated for over 30 years, is easy to use and has been the gold standard in various trials to evaluate sedation. The level of sedation increases as the value in the scale rises.17–20 Level 1 corresponds to a patient who is awake, anxious or agitated; level 2 represents a collaborative, quiet, oriented patient that opens his/her eyes spontaneously; level 3 represents a patient with closed eyes but who rapidly responds to verbal stimuli. Level 4 applies to a patient who is asleep, still, with eyes closed and responds promptly to strong tactile or verbal stimuli; level 5 corresponds to a slow responder, a patient who only responds to strong or painful stimuli; level 6 indicates a patient that fails to respond to any kind of stimulus.

Additionally, a Likert type satisfaction scale was used to subjectively evaluate the patient's satisfaction with the subarachnoid anesthesia under sedation. The survey was administered in the recovery room at the end of the surgery and was limited to describing the patient's satisfaction with the administration of the anesthesia but did not assess the time elapsed between the administration of the anesthesia and the end of the procedure. This scale is not yet validated.21 1 – extremely satisfied, 2 – satisfied, 3 – low satisfaction, 4 – unsatisfied, and 5 – extremely unsatisfied.

Analysis of the dataThe measurement of the categorical variables was reported in absolute figures and percentages. The differences between the baseline characteristics and the post-intervention values were estimated using hypothetical tests. The Chi square test and the exact Fisher test were used for qualitative variables, as appropriate. The quantitative variables checked for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and group comparisons were based on ANOVA. The analysis was supported with Epi Info v7 and Stata software.

Ethical considerationsThe trial was compliant with the Declaration of Helsinski and the current Colombian regulations (Resolution No. 008430, 1993 of the Ministry of Health and Resolution 2378, 2008 on good clinical practices). None of the actions infringed the ethical considerations thereof. An evaluation by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital was required. The committee endorsed the trial. A report of the individual informed consent of the patients was submitted.

ResultsSeventy-five patients were included, 36 females (48%) and 39 males (52%). The average age was 41.9±12.3 years; the average body weight was 67.3±9kg; height 1.7±0.05m and the body mass index was 24.5±2.9kg/m2.

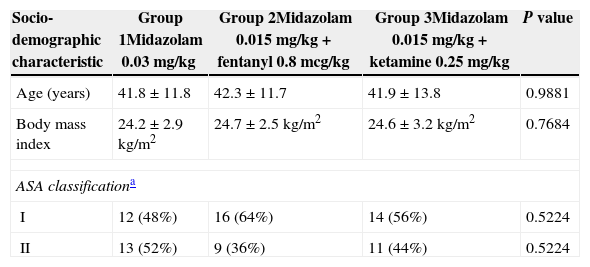

The gender distribution was similar for the three groups (P=0.8519). Thirteen females (52%) and 12 males (48%) were included in Group 1; Group 2 included 11 females (44%) and 14 males (56%); and Group 3 included 12 females (48%) and 13 males (52%). The age ranged from 18 to 60 years old. There were no significant statistical differences in the socio-demographic characteristics of the three groups, as shown in Table 1. Patients with ASA>II were excluded from the trial.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the population.

| Socio-demographic characteristic | Group 1Midazolam 0.03mg/kg | Group 2Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+fentanyl 0.8mcg/kg | Group 3Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+ketamine 0.25mg/kg | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.8±11.8 | 42.3±11.7 | 41.9±13.8 | 0.9881 |

| Body mass index | 24.2±2.9kg/m2 | 24.7±2.5kg/m2 | 24.6±3.2kg/m2 | 0.7684 |

| ASA classificationa | ||||

| I | 12 (48%) | 16 (64%) | 14 (56%) | 0.5224 |

| II | 13 (52%) | 9 (36%) | 11 (44%) | 0.5224 |

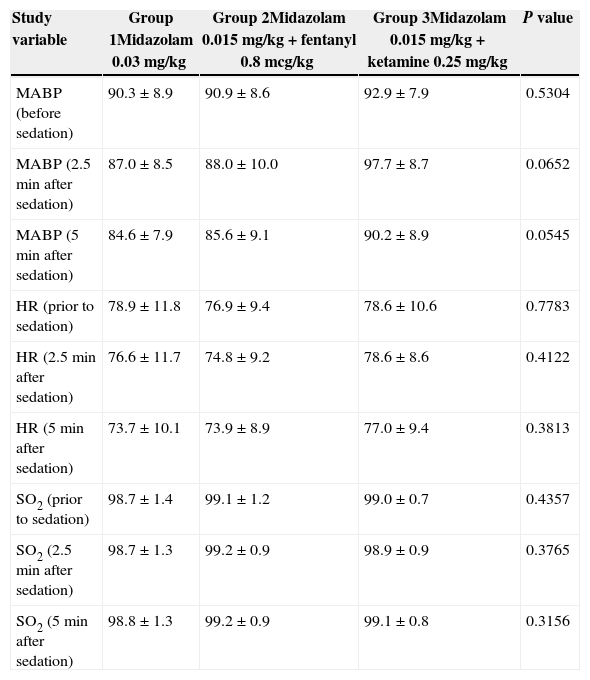

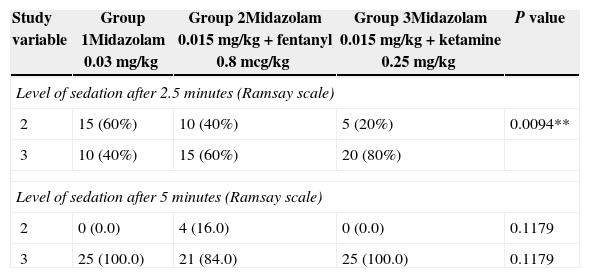

There were no significant statistical differences in the hemodynamic variables of each group, as shown in Table 2. The patients’ values according to the Ramsay scale at 2.5 and 5min were 2 and 3, respectively (Table 3).

Hemodynamic variables of the study.

| Study variable | Group 1Midazolam 0.03mg/kg | Group 2Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+fentanyl 0.8mcg/kg | Group 3Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+ketamine 0.25mg/kg | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MABP (before sedation) | 90.3±8.9 | 90.9±8.6 | 92.9±7.9 | 0.5304 |

| MABP (2.5min after sedation) | 87.0±8.5 | 88.0±10.0 | 97.7±8.7 | 0.0652 |

| MABP (5min after sedation) | 84.6±7.9 | 85.6±9.1 | 90.2±8.9 | 0.0545 |

| HR (prior to sedation) | 78.9±11.8 | 76.9±9.4 | 78.6±10.6 | 0.7783 |

| HR (2.5min after sedation) | 76.6±11.7 | 74.8±9.2 | 78.6±8.6 | 0.4122 |

| HR (5min after sedation) | 73.7±10.1 | 73.9±8.9 | 77.0±9.4 | 0.3813 |

| SO2 (prior to sedation) | 98.7±1.4 | 99.1±1.2 | 99.0±0.7 | 0.4357 |

| SO2 (2.5min after sedation) | 98.7±1.3 | 99.2±0.9 | 98.9±0.9 | 0.3765 |

| SO2 (5min after sedation) | 98.8±1.3 | 99.2±0.9 | 99.1±0.8 | 0.3156 |

MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; HR, heart rate; SO2, oxygen saturation.

** P value comparing Groups 1 and 3.

Source: Authors.

Ramsay scale value of the patient with the guideline used.

| Study variable | Group 1Midazolam 0.03mg/kg | Group 2Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+fentanyl 0.8mcg/kg | Group 3Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+ketamine 0.25mg/kg | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of sedation after 2.5 minutes (Ramsay scale) | ||||

| 2 | 15 (60%) | 10 (40%) | 5 (20%) | 0.0094** |

| 3 | 10 (40%) | 15 (60%) | 20 (80%) | |

| Level of sedation after 5 minutes (Ramsay scale) | ||||

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (16.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1179 |

| 3 | 25 (100.0) | 21 (84.0) | 25 (100.0) | 0.1179 |

Source: Authors.

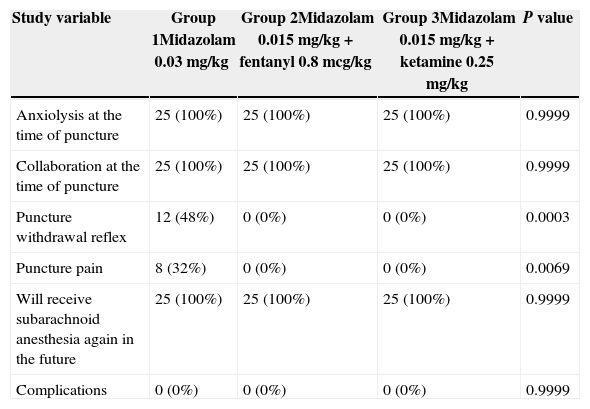

All of the patients in the trial received anxiolysis, collaborated with the puncture and said that they would not be afraid to receive subarachnoid anesthesia again. None of the patients experienced any complications as shown in Table 4. Patient satisfaction with the sedation guidelines used was high, as indicated on Table 5.

Effects of the sedation guidelines on the patient.

| Study variable | Group 1Midazolam 0.03mg/kg | Group 2Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+fentanyl 0.8mcg/kg | Group 3Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+ketamine 0.25mg/kg | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiolysis at the time of puncture | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 0.9999 |

| Collaboration at the time of puncture | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 0.9999 |

| Puncture withdrawal reflex | 12 (48%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0003 |

| Puncture pain | 8 (32%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0069 |

| Will receive subarachnoid anesthesia again in the future | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 0.9999 |

| Complications | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.9999 |

Source: Authors.

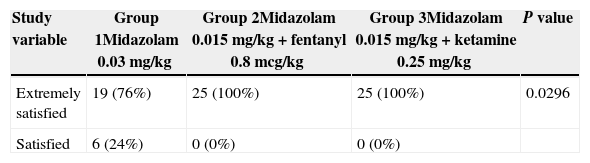

Level of satisfaction using the sedation guidelines for subarachnoid anesthesia.

| Study variable | Group 1Midazolam 0.03mg/kg | Group 2Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+fentanyl 0.8mcg/kg | Group 3Midazolam 0.015mg/kg+ketamine 0.25mg/kg | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely satisfied | 19 (76%) | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 0.0296 |

| Satisfied | 6 (24%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Source: Authors.

The participants in Group 1 that received Midazolam only expressed lower satisfaction as compared to the other two groups; however, the three sedation guidelines showed good efficacy.

Forty-eight patients (90.6%) required a single puncture for the administration of the subarachnoid anesthesia and seven patients (9.3%) required two punctures. This shows that the technique was easily applied.

Despite the evidence of slight nistagmus in the patients receiving ketamine, this was not reported as a complication; there were no delusions, dizziness, diplopia, unconscious reverie, and shallow breathing or CO2 retention.

DiscussionIt has been documented that over 50% of the patients are anxious prior to a regional block. The administration of sedation, whether as a single dose or in a continuous infusion is extremely helpful to get the patient's collaboration. Anxyolysis provides comfort, satisfaction and facilitates the job of the anesthesiologist when doing the subarachnoid puncture. In this trial we chose to use sedation guidelines for single intravenous dose because they are easy to follow and avoid the use infusion pumps that represent additional costs.13,15,22–25

The final analysis indicates that all of the sedation guidelines followed in this trial are effective in patients undergoing subarachnoid anesthesia; however, the best results were observed with the guidelines combining midazolam and an intravenous analgesic agent such as fentanyl or ketamine, at lower doses of both agents, as recommended by Reves et al.26

Various authors believe that levels 2 or 3 in Ramsay's scale – conscious sedation – are ideal for a regional anesthetic procedure.27–29 The patients that underwent sedation with the guidelines herein achieved these levels.

Withdrawal reflex is defined as the motor response intended to protect the body from painful stimuli. The withdrawal reflex occurred mostly in Group 1 patients when placing the needle in the patient's back to administer the subarachnoid anesthesia; these were the patients that received single dose intravenous midazolam (P=0.0003). The difference was statically significant. Painful puncture (P=0.0069) and a larger number of puncture attempts were also seen in this group of patients, probably because this guideline did not include the combined use of an analgesic agent and the withdrawal reflex caused greater difficulty for the block. There is a shortage of trials that evaluate these parameters.10

The use of a subjective tool to measure patient satisfaction using sedation for subarachnoid anesthesia showed that the patients treated with midazolam+fentanyl or midazolam+ketamine expressed higher satisfaction. However, the fact that the scale used is not validated represents a limitation of the trial.

It may be helpful to undertake a trial with a larger group of patients in order to establish the superior efficacy of one of the guidelines used.

Sedation was a useful tool when administering the subarachnoid anesthesia to calm down the patient, improve comfort and decrease pain, with considerable safety and minimal side effects, in addition to very few hemodynamic changes and free of complications. Sedation also results in improved conditions to do the puncture, a simpler technique with less failed attempts and a high level of satisfaction. The patient will be less fearful of future procedures under subarachnoid anesthesia in the OR.

ConclusionsThe three sedation guidelines suggested for administering subarachnoid anesthesia were effective. Better outcomes were seen with the use of midazolam+fentanyl or midazolam+ketamine.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingColciencias through the “Virginia Gutiérrez de Pineda” Young Researchers and Innovators Program”, Cartagena University and the author's personal funds.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: José BGF, Doris GC, Roberto PR, William LB, Enrique RC. Comparación de 3 pautas de sedación para pacientes sometidos a anestesia subaracnoidea. ensayo clínico aleatorizado, simple ciego. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2015;43:122–128.