Combined oral contraceptives (COCs), use in individuals are associated with increased risk of thrombotic events. This highlights the significance of assessing the impact of COC on promoting coagulation and endothelial activation in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed Sprague Dawley rats.

MethodsTwenty (20) five-weeks-old female Sprague Dawley rats weighing between 150 and 200g were subjected to both LFD and HFD-feeding for 8-weeks to determine its influence on basic metabolic status, hemostatic profile, hemodynamic parameters (blood pressure and heart rate), as well as selected biomarkers of coagulation (tissue factor and D-dimer) and endothelial activation (Von Willebrand factor and nitric oxide). Thereafter HFD-fed animals were treated with receive high dose combined oral contraceptive (HCOC) and low dose combine oral contraceptive (LCOC) for 6 weeks.

ResultsOur results showed that beyond weight gain, HFD-feeding was associated with hyperglycemia, increased mean arterial pressure, and reduced nitric oxide levels when compared with LFD group (p<0.05). Interestingly, treatment with high dose of COC for 6-weeks did not significantly alter atherothrombotic markers (p>0.05). However, this study is not without limitation as regulation of these markers remains to be confirmed within the cardiac tissues or endothelial cells of these animals.

ConclusionHFD-feeding orchestrate the concomitant release of pro-coagulants and endothelial activation markers in rats leading to haemostatic imbalance and endothelial dysfunction. Short-term treatment with COC shows no detrimental effects in these HFD-fed rats. Although in terms of clinical relevance, our findings depict the notion that the risk of CVD in association with COC may depend on the dosage and duration of use among other factors especially in certain conditions. However, additional studies are required to confirm these findings, especially long-term effects of this treatment within the cardiac tissues or endothelial cells of these animals in certain conditions relating to postmenopausal state.

El uso de anticonceptivos orales combinados (AOC) en individuos se asocia con un mayor riesgo de eventos trombóticos. Esto resalta la importancia de evaluar el impacto de los AOC en la promoción de la coagulación y la activación endotelial en ratas Sprague Dawley alimentadas con una dieta alta en grasas (HFD).

MétodosVeinte (20) ratas Sprague Dawley hembra de 5semanas de edad con un peso entre 150-200g fueron tratadas mediante una alimentación con dieta baja en grasas (LFD) y alta en grasas (HFD) durante 8 semanas para determinar su influencia en el estado metabólico básico, perfil hemostático, parámetros hemodinámicos (presión arterial y frecuencia cardíaca), así como biomarcadores seleccionados de coagulación (factor tisular y D-dímero) y activación endotelial (factor de von Willebrand y óxido nítrico). Posteriormente, los animales alimentados con HFD fueron tratados con dosis alta de anticonceptivo oral combinado (AOC-AL) y dosis baja de anticonceptivo oral combinado (AOC-BL) durante 6 semanas.

ResultadosNuestros resultados mostraron que, además del aumento de peso, la alimentación con HFD se asoció con hiperglucemia, aumento de la presión arterial media y niveles reducidos de óxido nítrico en comparación con el grupo LFD (p<0,05). Curiosamente, el tratamiento con dosis alta de AOC durante 6 semanas no alteró significativamente los marcadores aterotrombóticos (p>0,05). Sin embargo, este estudio no está exento de limitaciones, ya que la regulación de estos marcadores aún debe confirmarse en los tejidos cardíacos o las células endoteliales de estos animales.

ConclusiónLa alimentación con HFD orquesta la liberación concomitante de procoagulantes y marcadores de activación endotelial en ratas, lo que conduce a un desequilibrio hemostático y disfunción endotelial. El tratamiento a corto plazo con AOC no muestra efectos perjudiciales en estas ratas alimentadas con HFD. Aunque, en términos de relevancia clínica, nuestros hallazgos representan la idea de que el riesgo de enfermedad cardiovascular en relación con el AOC puede depender de la dosis y la duración de uso, entre otros factores, especialmente en ciertas condiciones. Sin embargo, se requieren estudios adicionales para confirmar estos hallazgos, especialmente los efectos a largo plazo de este tratamiento en los tejidos cardíacos o las células endoteliales de estos animales en ciertas condiciones relacionadas con el estado posmenopáusico.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) account for at least a third of the mortality occurring in low and middle-income countries (LMIC).1,2 Despite the advancements in the therapeutics and management of patients with chronic disease,3 CVD still account for a substantial number of deaths in people living with metabolic complications.4 Obesity remains a predominant risk factor for thrombosis which is characterized by increased plasma levels or activity of coagulation factors and fibrinolytic proteins which contribute to major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs).5

Of note, the pathological enlargement of the adipose tissue in obesity elicits the release of pro-inflammatory molecules that induce damage to the endothelium.6,7 This further results in the altered release of nitric oxide (NO) and negatively affect other vasodilatory metabolites leading to endothelial dysfunction8,9 and arterial stiffening.10,11 Furthermore, the endothelium may be transformed from an antithrombotic to prothrombotic state in obesity which may orchestrate haemostatic imbalances.12–14 During a prothrombotic state, tissue factor (TF), von Willebrand factor (vWF) and P-selectin promote the adhesion of platelet on the endothelium.15–19

The use of oral contraceptives especially the combined oral contraceptives (COCs) is a commonly modern method for birth control.20,21 However, the use of COC is also associated with endothelial and haemostatic dysregulation which increases the risk of CVD.22,23 Some of the established mechanism by which COC impact the vasculature include the activation of aldosterone-mineralocorticoid receptor axis among others.20,24 However, findings are inconsistent and others indicate no correlation exist between the use of COC and changes in major makers of endothelial function like NO and endothelin-1 in premenopausal women.25 In contrast, experimental study suggests that COC treatment may alter endothelial function and haemostasis and ultimately promote inflammation.26

Nonetheless, there is a need to continuously assess the impact of hormonal contraceptives for their potential effects in causing vascular dysfunction in women at risk of developing CVD.27 Beyond providing insight into the pathophysiology of vascular disease in those with metabolic anomalies, this would enhance our understanding on the potential influence of oral contraceptives in driving CVD-risk among susceptible individuals.28,29 In the current study, we first assess the impact of high fat diet (HFD) on dysregulating biomarkers of coagulation and endothelial activation in Sprague Dawley rats. We further investigated the influence of COC treatment in these HFD-fed rats.

Materials and methodsAnimal handlingsTwenty (n=20) five-week-old female Sprague Dawley rats weighing between 150 and 200g were used for this study. The animals were purchased and housed at the Biomedical Research Unit (BRU) of the University KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN; South Africa). Animal handling followed guidelines and principles, as published by the Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.30 Briefly the animals acclimatized for 2 weeks before commencement of the study, with an unrestricted access to food and water throughout the project. This was done within an environment-temperature (22±2°C), humidity (55±5%), controlled 12-h light cycle (6:00–18:00) and dark cycle (18:00–6:00). Ethical clearance for this study was granted by the UKZN animal research ethics committee, ethics registration number AREC/00003067/2021.

Study designThe study contained two major experiment phases. The first experiment group comprised of 10 female animals (n=5/group) that were kept on a HFD (containing 20% protein and 60% fat; #D12492) for eight weeks and a control group which was randomized to receive LFD (containing 20% protein and 10% fat; #D12450) (Research Diets, Inc.; New Jersey, United States). The diet composition and duration of HFD-feeding follows previously published literature.31 The food and water intake were measured weekly via metabolic cages (Techniplats, Labotec, South Africa). Moreover, body weights were monitored weekly while the hemodynamic and haemostatic changes were determined at the last week of the experiment to minimize stress.

The second experimental phase contained 10 rats (n=5/group) that were kept on a HFD for 8 weeks before receiving levonorgestrel-containing oral contraceptives (COC) for 6 weeks,32 at low dose (4.5μg of levonorgestrel and 0.9μg ethinylestradiol) or high dose (9μg levonorgestrel and 1.8μg ethinylestradiol) (Aspen Pharmacare, South Africa).33 Additional rats (n=10), exposed to HFD (n=5/group) or LFD (n=5/group) alone, served as controls for diet-induced obesity and experimental control, respectively. Treatments were prepared in distil water.34 All the treatments were administered daily via oral gavage while the animals were regularly monitored for adverse reaction, and the cages were cleaned daily. After 6 weeks of COC treatment blood samples were drawn from the lateral tail vein into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) microtainer and vacutainer citrate tubes (BD Bioscience, United States) for further analysis (Fig. 1).

Experimental design. 20 five-week-old female Sprague Dawley rats were used in this study. In experiment A rats were randomly allocated into two diet groups low-fat diet (LFD) and high-fat diet (HFD), (n=5) for a period of eight weeks. In experiment B, animals kept on HFD (n=10) were randomized to receive high dose combined oral contraceptive (HCOC) and low dose combine oral contraceptive (LCOC) for six weeks, to give total experimental period to be 14 weeks. The animal weights and metabolic changes were monitored weekly.

Hemodynamic parameters, including {systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure (MAP)} were determined via the tail-cuff method using the non-invasive digital blood pressure (BP) system (BIOPAC System, NTBP250, California, USA). Briefly, the machine has a built-in pump that automatically inflates and deflates the rat tail cuff to provide a linear drop in pressure. The equipment was calibrated each day before measurements and the animals were placed in a restrainer with a cuff attached to a heated tail to allow effective adaptation and habituation. During the day of measurement, the animals were kept warm at ±37°C in an enclosed chamber (IITC Model 303sc Animal Test Chamber, IITC Life Sciences, Woodlands Hills, California, USA) for 15min before blood pressure recording to make the pulsations of the tail artery detectable. All measurements were conducted before mid-day to avoid diurnal variation. The mean arterial pressure was determined as described previously.35

Hemostatic assessmentHemostatic assessment was determined via the bleeding time which gives an oversight of changes in the primary hemostatic process that occur prior to the clotting phase. Notably, the primary hemostatic phase involves formation of platelet plug during which vWF are released which facilitate platelet adhesiveness to the vascular wall in order to promote stoppage of blood.15,36 Thus, the evaluation of both total blood loss and time to cessation of blood flow are important factor to be considered when evaluating effect of certain anti-platelet therapy.37 Briefly, we assessed the bleeding time in the animals via the tail cut method and this was recorded as previously demonstrated.36 The tail of the rat was warmed for 1min in water at 40°C and then dried before a small cut was made in the middle of the lower portion of the tail with a scalpel. Bleeding time was recorded when the first drop of blood was collected. Bleeding time was monitored at 30s intervals until bleeding stopped.

Biochemical analysisPlasma levels of TF, D-dimer, NO and vWF were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Houston, Texas, USA). All assays were performed according to the recommended protocol. ELISA used were highly sensitive, and no results were below the detection limits. Briefly, the detection limit were 31.25pg/mL for TF, 78.13ng/mL for D-dimer, 0.16μmol/L for NO and 0.16ng/mL for vWF. The inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) were <10% for TF, D-dimer, vWF, and 3.7% for NO.

Statistical analysisAll experimental data were expressed as means±standard error of mean (SEM). Normality testing was performed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Dallal–Wilkinson–Lillie. The mean differences between the LFD and HFD-fed groups were determined using unpaired Student t-test for parametric data and reported as means±standard error of mean (SEM). Correlations were performed between MAP, coagulation and endothelia activation markers using Pearson coefficients. Statistical significance for measured variables was determined by one-way (treatment factor) analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the comparison of the mean values of variables among the experimental groups. A post hoc Tukey's multiple comparisons test was performed if the F-value reached statistical significance (p<0.05). All the statistical analysis were performed using the GraphPad Prism version 8.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., California, USA).

ResultsMetabolic status of rats fed a high fat diet (HFD) compared to low fat diet (LFD) for 8 weeksThere was a significant decrease in food intake (g/kg/day) in HFD-fed group (37.2±1.3) when compared with LFD-fed group (51.6±2.3) (p<0.001) (Table 1). Whereas water intake (mL/kg/day) was significantly increased in HFD-fed group (119±4.6) when compared with LFD-fed group (88.1±3.8) (p<0.001) (Table 1). Furthermore, HFD-fed rats (289±4.1) showed significant weight gain (g) in comparison to LFD-fed rats (270±5.2) (p=0.002) (Table 1). More so, fasting glycemia (mmol/L) was significantly increased in HFD-fed groups (5±0.5) when compared with LFD-fed group (3.8±0.6) (p≤0.01) (Table 1).

Characteristic features of rats exposed to high fat diet (HFD)-feeding in comparison to the low-fat diet (LFD) group.

| Parameters | LFD group | HFD group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic status | |||

| Food intake (g/kg/day) | 51.6±2.3 | 37.2±1.3 | <0.0001 |

| Water intake (mL/kg/day) | 88.1±3.8 | 119±4.6 | <0.0001 |

| Body weight (g) | 270±5.2 | 289±4.1 | 0.02 |

| Fasting glycemia (mmol/L) | 3.8±0.6 | 5±0.5 | 0.006 |

| Hemodynamics | |||

| SBP (mmHg) | 129±5.7 | 137±7.2 | 0.082 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 90.8±2.2 | 92.4±0.9 | 0.166 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 103.6±1.1 | 107.2±2.9 | 0.03 |

| HR (bpm) | 333±14.2 | 380±20.7 | 0.174 |

| Hemostatic profile | |||

| Bleeding time (s) | 204±39.1 | 156±32.9 | 0.069 |

| TF (pg/mL) | 53.84±6.7 | 76.6±9.9 | 0.09 |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 175±17.1 | 200±23 | 0.403 |

Results expressed as mean±standard error. Significance between groups (p<0.05) shown in boldface. Key: SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; MAP: mean arterial pressure; HR: heart rate; TF: tissue factor.

The systolic and diastolic blood pressure were comparable in both diet groups (p>0.05); however, the MAP (mmHg) was significantly higher in HFD-fed group (107.2±2.9) when compared to the LFD-fed group (103.6±1.1) (p≤0.03). In addition, the heart rate of both diet groups was comparable (p>0.05) (Table 1).

Haemostatic profile and endothelial markers of LFD and HFD-fed rats for 8 weeksThe bleeding time which was used to determine the haemostatic changes between both diet groups was comparable (p>0.05) (Table 1). Furthermore, plasma levels of tissue factor and D-dimer to determine changes in the clotting cascade were also comparable between diet groups (p>0.05) (Table 1). In terms of endothelial activation, the plasma levels of Von Willebrand factor were comparable between diet groups (Fig. 2A). Whereas the plasma levels of NO were significantly lower in HFD-fed group (8.1±0.5) when compared to LFD-fed group (10±1.3) (p<0.05) (Fig. 2B).

Effects of low-fat diet (LFD) and high fat diet (HFD) feeding on endothelial activation including (A) Von Willebrand factor (B) nitric oxide levels. All results are presented as mean±SEM with the significance represented by *p<0.05. Key: LFD: low-fat diet; HFD: high-fat diet; ns: (not significant).

Next, we determined the relationship that exists between HFD-feeding and the presence of pathological features of atherothrombosis in rats. This was done by assessing if there was any association between MAP and the dysregulation of makers of coagulation and endothelial activation (Fig. 3). The result showed that MAP was associated with TF (r=0.97, p<0.007) and D-dimer (r=0.87, p<0.02) (Fig. 3A and B). MAP was also associated with Von Willebrand factor (r=0.88, p<0.01) and NO (r=−0.86, p<0.02) (Fig. 3C and D).

Association between Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and biomarkers of coagulation cascade like tissue factor (TF) and D-dimer (A, B) as well as biomarkers of endothelia activation such as Von Willebrand factor (VWF) and nitric oxide (NO) (C, D) after 8 weeks high fat diet (HFD)-feeding in rats. Correlations are presented as Pearson r 95% confidence interval (p<0.05).

The body weights were comparable across experimental groups (p>0.05) (Table 2). However, food intake (F(3, 16)=3.674; p=0.03) varied across the experimental groups. The post hoc analysis showed a significant decreased food intake in HFD fed rats that received the high dose COC when compared with LFD-fed rats (p≤0.05) (Table 2). Meanwhile, water intake was comparable among the groups despite COC treatment group displaying non-significant increase in this parameter (p>0.05) (Table 2). More so, fasting glycemia was comparable across experimental groups (p>0.05) (Table 2).

Characteristics of animals following 6-week short-term treatment with combined oral contraceptive (COC) (n=5/group).

| Parameters | LFD | Untreated HFD | HFD+low dose COC | HFD+high dose COC | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic status | |||||

| Food intake (g/kg/day) | 67.6±2.3 | 61.6±3.6 | 62.1±2.4 | 60±5.9a | 0.0347 |

| Water intake (mL/kg/day) | 102.5±4.6 | 107.6±6.5 | 110±4.4 | 116.5±12.6 | 0.08 |

| Body weight (g) | 287.2±9.9 | 299.8±17 | 281.8±26.2 | 295.2±11.3 | 0.388 |

| Fasting glycemia (mmol/L) | 3.52±0.52 | 4±0.37 | 3.58±0.49 | 3.94±0.59 | 0.3424 |

| Hemodynamics | |||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 125.2±5.4 | 135.8±8 | 137.0±7 | 140.4±7.4a | 0.0196 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 88.2±4.7 | 91.4±4.8 | 91.8±0.84 | 92.6±6.15 | 0.5827 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 100.4±4.3 | 106.4±3.1 | 106.8±2.6 | 108.4±5.23a | 0.025 |

| HR (bpm) | 343.2±39.5 | 361.6±27.1 | 357±17 | 385.6±27.8 | 0.1775 |

| Hemostatic profile | |||||

| Bleeding time (s) | 186±33 | 168±50.2 | 120±37 | 96±25.1ab | 0.005 |

Data presented as mean±SEM. SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; MAP: mean arterial pressure; HR: heart rate.

Significance (ap<0.05 vs LFD; bp<0.05 vs HFD) shown in boldface.

The systolic blood pressure (F(3, 16)=4.390; p=0.02) differed across the experimental groups. HFD-fed rats receiving high dose COC showed a significant increased systolic blood pressure when compared with the LFD group (p≤0.05) (Table 2). While the mean arterial pressure (F(3, 16)=3.4; p=0.03) also varied across the experimental group, HFD-fed rats receiving high dose COC showed a significant increased mean arterial pressure when compared with the LFD group (p≤0.05) (Table 2). Meanwhile, the diastolic blood pressure and heart rate were comparable across all the experimental groups following 6 weeks of COC treatment (p>0.05) (Table 2). Notably, the bleeding time assessment (F(3, 16)=4.390; p=0.02) also differed across the experimental groups. HFD-fed rats receiving high dose COC showed significant increased bleeding time when compared with the LFD and HFD-fed rats (p<0.05) (Table 2).

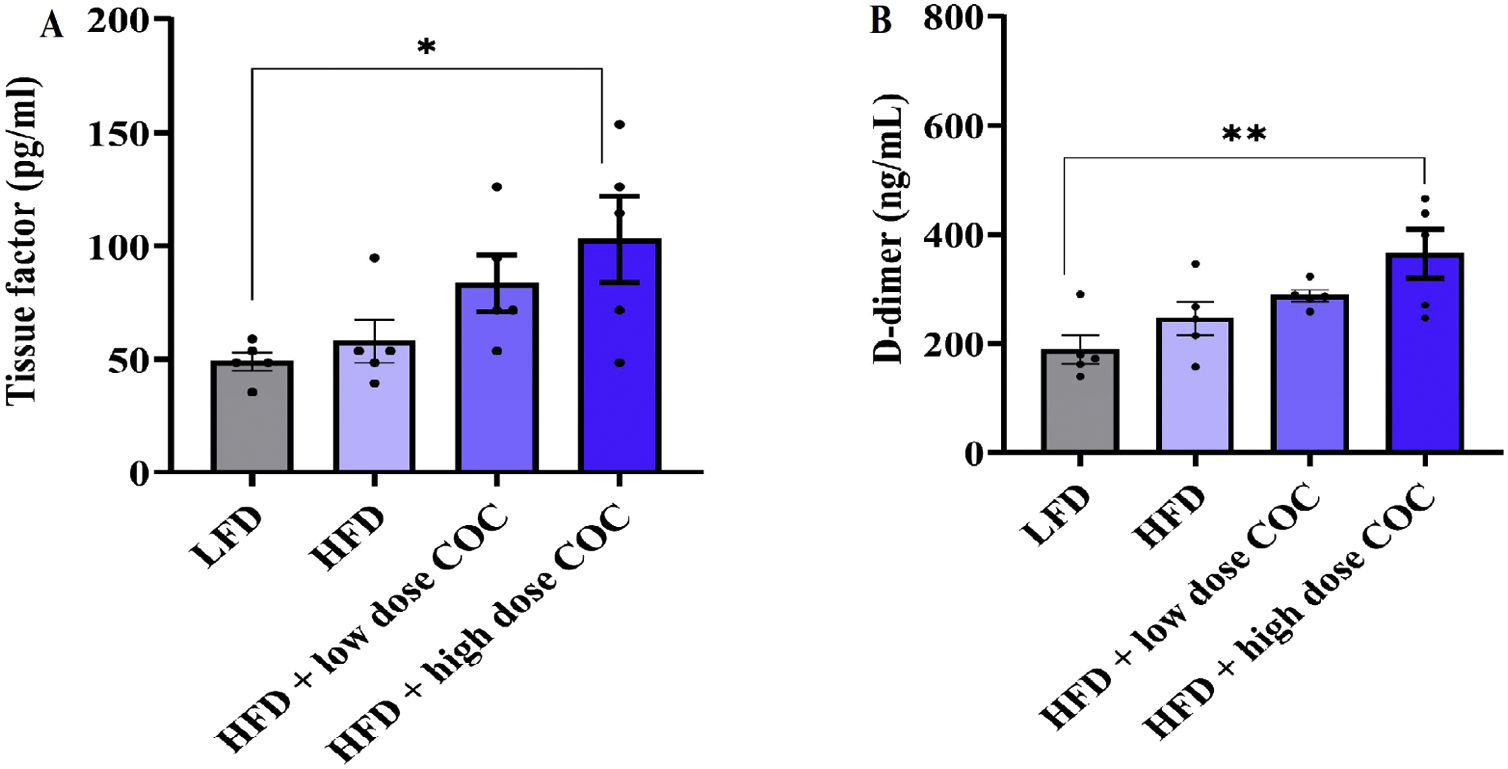

Effect COC on biomarkers of coagulation and endothelial activation haemostatic profile in HFD-fed ratsTo determine changes in the coagulation cascade, the plasma levels of tissue factor and D-dimer were determined following 6 weeks of COC treatment. Our data showed a varied plasma levels of tissue factor (F(3, 16)=3.862; p=0.03) and D-dimer (F(3, 16)=5.84; p=0.007) across the experimental groups respectively. Both tissue factor and D-dimer levels were significantly increased in HFD-fed rats receiving high dose COC when compared with LFD-fed rats (p<0.05; p<0.001) (Fig. 4A and B). Furthermore, the plasma levels of Von Willebrand factor and NO were measured to determine changes in endothelial activation. Briefly, Willebrand factor (F(3, 16)=3.73; p=0.03) and NO (F(3, 16)=5.03; p=0.01) also differed across the experimental groups respectively. HFD-fed rats receiving high dose COC demonstrated a significant increase in plasma levels of Von Willebrand factor when compared with LFD-fed rats (p<0.05) (Fig. 5A). Whereas plasma levels of NO are significantly lower in the HFD-fed rats receiving high dose COC when compared with LFD-fed rats (p<0.001) (Fig. 5B).

Effect of combined oral contraceptive treatment on biomarkers of coagulation cascade like tissue factor (A) and D-dimer (B). All results are presented as mean±SEM. Significance indicated between LFD and HFD+high dose COC. *p<0.05; **p<0.001. Key: LFD: low fat diet; HFD: high fat diet; COC: combined oral contraceptive.

Effect of combined oral contraceptive treatment on biomarkers of endothelia activation like Von Willebrand factor (A) and nitric oxide (B). All results are presented as mean±SEM. Significance indicated between LFD and HFD+high dose COC. *p<0.05; **p<0.001. Key: LFD: low fat diet; HFD: high fat diet; COC: combined oral contraceptive.

In this present study we assessed the impact of HFD-feeding on selected biomarkers of coagulation and endothelia activation in HFD-fed rats. Firstly, HFD-feeding for 8-weeks promoted weight gain which was accompanied by alterations in food and water intake when compared with LFD-fed rats (Table 1). Interestingly, such phenotypic changes were similar to previous studies in experimental animals on HFD showing characteristic feature of metabolic syndrome.38–40 In fact, our previous study has shown that 8-week HFD-feeding led to the development of metabolic syndrome and increased levels of biomarkers of atherothrombotic disorders and CVD.41,42

In our study, the systolic and diastolic blood pressure including the heart rate were not affected by 8-weeek-treatment with HFD. It is noteworthy that the causal role of dietary fat on hemodynamic changes in animal models of obesity is subject to variation due to the strain of animal.38 However, evidence from our study corroborates with previous studies where HFD over 10 weeks did not alter the hemodynamic profiles of the animals.43,38 Nonetheless, the MAP was significantly higher in HFD-fed rats when compared with LFD-fed rats. This agreed with our results showing that MAP was associated with TF, D-dimer, and NO in these HFD-fed rats.

Furthermore, our results indicated that exposure of rats to HFD for 8-weeks in addition to COC treatment for a 6-week period did not affect the weight gain and fasting glycemia in these the animals, except for food intake, which was significantly reduced in response to a high dose of COC (Table 2). Although human study showed an association between COC and dyslipidemia.44–46 Alterations in the lipid profile levels can be attributed to the lipogenic effect of estrogen in which liver lipogenesis is increased and results in elevated levels of triglycerides and LDL levels. Furthermore, the progestin component of OCs may also increase the hepatic lipase enzyme activity, hence decreasing the serum HDL levels and potentially promoting plague formation during the early stage of atherosclerosis.45,47 Our results indicated that COC treatment (especially the high dose) may have a significant role in influencing food intake, sex hormones, and eating behavior in female rats, as previously reported in similar settings.48–50 However, the short-term treatment period of 6-weeks in our study may not be sufficient to induce marked changes in HFD-fed rats which depicts the notion of reduced metabolic risk upon short-term COC exposure. Nonetheless, it remained important to determine how COC treatment affected other markers related to the development of CVD.

Noteworthy, treatment of HFD-rats with a high-dose of COC significantly increased the systolic blood and MAP when compared to LFD group. However, such effects occurred without any changes in the hemodynamic profiles, including the diastolic blood pressure and heart rate. While the outcome of our study corroborates previous findings,51–53 it also suggested that a dose-dependent relationship between high COC and hemodynamic changes exist. In principle, endogenous female sex hormones are known to be cardioprotective54 which maybe abrogated during hormonal contraceptive treatment thereby predisposing susceptible individuals to higher risk of MACEs in the presence of several comorbidities such as obesity, smoking and physical inactivity.27 For instance, the administration of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in women aged 50–59 years showed a cardioprotective effect by significantly reducing the coronary disease risk factor such coronary artery calcification immediately after menopause. However, HRT was associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease in women who have been menopausal for 10 or more years and who are older than 60 years.7,8

Importantly, beyond assessing the basic metabolic parameters, it remains essential to understand how different doses of COC affects some selected biomarkers of endothelial function in these HFD-rats. Obesity-related complications are multifactorial, and it encompasses alterations to blood flow, hypercoagulability, and endothelial dysfunction which all contribute to the early pathological process of atherothrombotic-CVD.55 Although eight weeks of HFD-feeding did not alter levels of TF and D-dimer in our study. In contrast, other studies reported changes in the coagulation cascade in HFD-fed mouse model.56,57 For instance, female C57Bl/6J mice demonstrated a prothrombotic phenotype after fourteen weeks of HFD-feeding.57 Cleuren et al. also showed early-onset in procoagulant shift in HFD fed C57BL/6J male mice which persisted during sixteen weeks of HFD-feeding.56 The physiological difference in the sex and specie of the animals in association with the handling of metabolic stress may contribute to the observed differential change in the coagulation cascade.58,59 However, the plasma levels of TF and D-dimer were significantly higher in HFD-fed rats receiving high COC when compared to LFD-fed rats in our study which contrast other previous finding where short-term ethinylestradiol treatment counteracts the prothrombotic phenotype in HFD-fed mice.57 However, the orchestrated haemostatic imbalance observed in our study is similar with clinical findings by others where the release of TF and dimer was relatively higher in COC users when compared with women who did not use COCs.60–62 The outcome of study suggests a dose-dependent relationship between COC and haemostatic changes in association with progestin type.63,64

TF plays an important role in the initiation of the extrinsic coagulation process which is complemented by the intrinsic pathway that ensures thrombin generation and clot production.65 D-dimer antigen originates as a product of the fibrinolytic system that regulates the removal of fibrin during clot formation.66 In principle, the fibrinolytic system physiologically counteracts the hypercoagulable condition and maintains normal circulation during haemostasis.67 However, haemostatic imbalance can cause excessive fibrin deposition inside the vascular channels and obstruct blood flow which may lead to MACEs such as arterial and venous thrombosis, ischemia, and myocardial infarction.67

In terms of endothelial changes, the result of our study showed a significant increase in plasma levels of NO in HFD-fed rats when compared to LFD-fed rats after 8 weeks of HFD feeding. Meanwhile the plasma levels of vWF were comparable between both diet groups. This corresponds with previous findings where NO level was reduced in HFD-fed rats.68–71 Although recent evidence showed the critical role of vWF in the thrombo-inflammatory complex during obesity72 where they mediate platelet aggregation and adhesion and promote leukocyte extravasation and several inflammatory responses.15 Nonetheless, our result contrasts other previous studies that reported elevated levels of vWF in HFD-fed experimental animals.15,55

Furthermore, HFD-fed rats treated with high dose COC for 6 weeks demonstrated increased levels of VWF while NO levels were significantly reduced when compared with the LFD. However, no significant change was observed when compared with HFD only group. The observed endothelial changes orchestrated by COC treatment may have resulted from vasoactive effect of the progestin component which is known to antagonize the vasodilatory effect of estrogen in healthy subjects.72,73 Our result also corroborates previous findings that showed reduced NO bioavailability during COC administration in non-obese animals.52

Of note, the association between the use of COC and the risk of CVDs events varies and it also depends on diverse factors.74 For instance, in a multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis that assessed the association of OC use and incident of heart failure (HF) in 3594 women, no overall increase in the risk of HF with OC use was reported.75 In fact, recent study by Dou et al. showed that OC use was associated with a 9% reduction in the risk of CVD events including HF, and the association was significantly modified by the duration of OC use.76 It is noteworthy that these studies did not report on the details of OC in terms of the formulation, dosage, and duration of use among the participants. In our study, we focused on the second-generation OC, and the outcome of our findings depict the notion that the short-term use of second-generation OC does not predispose to higher risk of CVD events. However, depending on the formulation, duration of use and the dosage of OC, the risk of CVD events may present with certain clinical manifestations. The limitations of this study include lack of determining vWF activity which is mainly secreted into circulation by endothelia cells. While vWF alone don’t offer a complete functional mechanism, vWF:Ristocetin ratio is important in associating vWF levels with CVD risk.77 Furthermore, TF activity and sources of NO were not determined. Thus, further studies are required to determine how the long-term COC treatment influences the activity of vWF and TF activity in certain conditions related to postmenopausal state.

ConclusionHFD-feeding aggravates the risk of atherothrombosis by orchestrating the concomitant release of pro-coagulants and endothelial activation markers leading to haemostatic imbalance and endothelial dysfunction. Short-term treatment with COC shows no detrimental effects. However, additional studies are required to confirm these findings, especially long-term effects of this treatment on CVD-related markers in conditions of obesity.

Authors’ contributionsOA and BBN conceptualized, designed the study, and drafted the manuscript. OA and BBN performed formal analysis, methodology and validation. OA performed Visualization. OA, BBN and PVD writing-review & editing. PVD and BBN-Supervision. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statementData generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors are grateful to the Biomedical Resource Unit, University of KwaZulu-Natal, UKZN for technical assistance.