Current guidelines recommend cardiovascular risk assessment as a preventive measure for cardiovascular diseases, whose fundamental etiology is arteriosclerosis. One of the tools used to estimate risk in clinical practice are atherogenic indices (AI), ratios between lipid fractions with well-established reference ranges. Despite its widespread use, there is still limited information on its clinical utility. In recent years, some research has reinforced the role of inflammation in the etiology and chronicity of the atherosclerotic process. The inclusion of inflammatory parameters in the AI calculation could improve its diagnostic performance in the detection of arteriosclerosis. We sought to evaluate a new AI as a ratio between C-reactive protein (CRP) values and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) values.

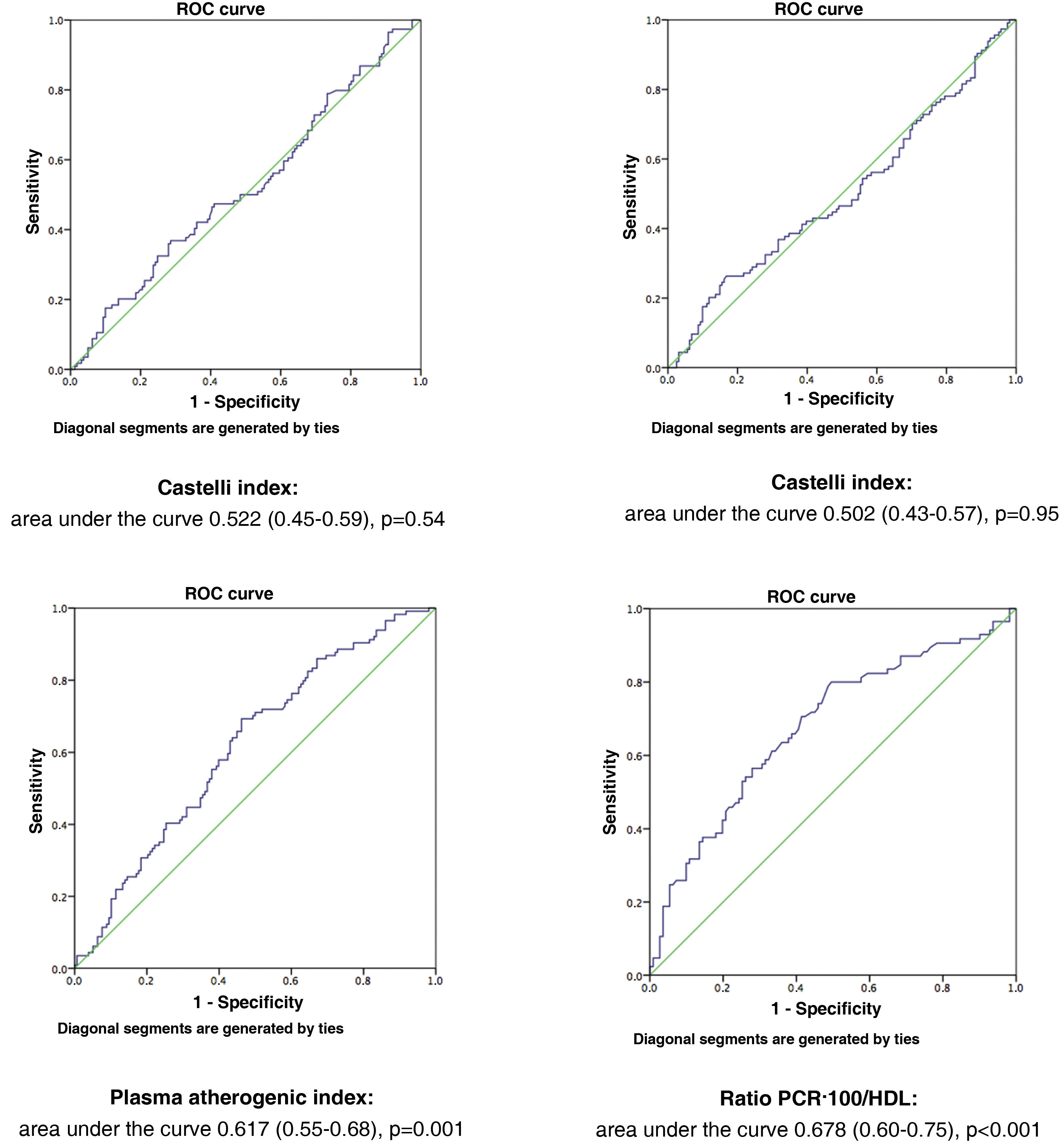

MethodsA total of 282 asymptomatic patients with no history of cardiovascular disease were included in the study. Laboratory tests with lipid profile and CRP, and carotid ultrasound to assess the presence of atheromatosis were performed in all of them. The new AI is established as the ratio between non-ultrasensitive CRP value in mg/dL (multiplied by 100) and HDL value in mg/dL. It was compared with the Castelli I and II indices, and the plasma atherogenic index. The optimal cut-off point of the new AI was value = 1 as determined by ROC curve, with an area under the curve of 0.678 (95% CI 0.60−0.75, P < .001).

ResultsMean age of patients was 60.4 ± 14.5 years. 118 patients (41.8% of total) had carotid arteriosclerosis. When evaluating the diagnostic performance of different AIs, we found that CRP·100/HDL ratio showed the highest values of sensitivity and positive predictive value (0.73 and 0.68, respectively) compared to the Castelli I and II indices, and the plasma atherogenic index. It was also the only predictor of carotid atheromatosis both when considering its values quantitatively [with OR 1.4 (95% CI 1.1−1.7, P = .005)], and qualitatively [with OR 2.9 (95% CI 1.5–5.5, P < .001) in patients with a CRP·100/HDL ratio >1].

ConclusionsThe new PCR·100/HDL index showed the best diagnostic performance in the detection of carotid atheromatosis compared to other classic AIs in this Spanish population of asymptomatic patients.

La valoración del riesgo cardiovascular aparece en las guías clínicas como medida de prevención de enfermedades cardiovasculares, cuya etiología fundamental es la arteriosclerosis. Una de las herramientas que se utiliza para estimar el riesgo en práctica clínica son los índices aterogénicos (IA), cocientes entre fracciones lipídicas con rangos de referencia bien establecidos. A pesar de su uso extendido, existe todavía información limitada sobre su utilidad clínica. En los últimos años, algunas investigaciones han reforzado el papel de la inflamación en la etiología y cronicidad del proceso aterosclerótico. La inclusión de parámetros inflamatorios en el cálculo de IA podría mejorar su rendimiento diagnóstico en la detección de arteriosclerosis. Nos propusimos evaluar un nuevo IA en forma de ratio entre los valores de proteína C reactiva (PCR) no ultrasensible y las cifras de colesterol unido a lipoproteínas de alta densidad [HDL].

MétodosSe incluyeron en el estudio 282 pacientes, asintomáticos, y sin historia de enfermedad cardiovascular. Se realizó en todos ellos analítica con perfil lipídico y PCR, y en el plazo inferior a un mes, ecografía carotídea para evaluar presencia de ateromatosis. El nuevo IA se estableció como el cociente entre valor de PCR no ultrasensible en mg/dL (multiplicado por 100) y valor de HDL en mg/dL. Se comparó con los índices de Castelli I y II, y el índice aterogénico del plasma. La curva COR determinó que el punto de corte óptimo del nuevo IA fue valor = 1, con un área bajo la curva de 0.678 (IC 95% 0.60−0.75, P < .001).

ResultadosLa edad media de la muestra fue 60.4 ± 14.5 años. 118 pacientes (41.8% del total) tenían arteriosclerosis carotídea. Al evaluar el rendimiento diagnóstico de los IA, encontramos que el ratio PCR·100/HDL mostró los valores más elevados de sensibilidad y valor predictivo positivo (0.73 y 0.68, respectivamente) en comparación con los índices de Castelli I y II, y el índice aterogénico del plasma. Además fue el único predictor de ateromatosis carotídea tanto al considerar sus valores de forma cuantitativa [con OR 1.4 (IC 95% 1.1−1.7, P = .005)], como cualitativa [con OR 2.9 (IC 95% 1.5–5.5, P < .001) en pacientes con ratio PCR·100/HDL > 1].

ConclusionesEl nuevo índice PCR·100/HDL mostró el mejor rendimiento diagnóstico en la detección de ateromatosis carotídea en comparación con otros IA clásicos, en una población española de pacientes asintomáticos.

Over the course of recent years, cardiovascular risk (CVR) assessment has been incorporated into clinical guidelines as a measure to prevent cardiovascular disease, regarded as one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in the West.1–3

The primary aetiology of ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease is the development of atherosclerosis, a complex chronic inflammatory process of multifactorial origin, characterised by impaired vascular function and progressive thickening of the intima and mean layer of the arteries. Its basic histological lesion is atheromatous plaque.4,5

It is well known that dyslipidaemia, and in particular elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL), is a significant risk factor in the premature onset of atherosclerosis, and as such is taken into account for the overall assessment of CVR by analytical determinations of the lipid profile.6,7 However, the use of isolated concentrations of lipid fractions (total cholesterol and triglycerides [TG]), the various types of lipoproteins (very low-density lipoprotein [VLDL], LDL, and high-density lipoproteins [HDL,] or even apolipoproteins (mainly apo-B, apo-AI, apo-AII, and apo-C) provide quantitative data, but fail to provide information regarding the balance between antherogenic and antiatherogenic lipoproteins. Consequently, evaluating CVR based solely on lipoprotein concentrations (cholesterol bound to LDL and/or HDL) is not optimum, especially in individuals with moderate to very high CVR.8

With the aim of improving CVR quantification in clinical practice, atherogenic indices (AI) have been used. These ratios typically consist of a numerator containing a lipid variable that correlates positively with CVR (e.g., total cholesterol or LDL) and a denominator that correlates negatively with CVR (e.g. HDL). The best known are the Castelli I (total cholesterol/HDL) and Castelli II (LDL/HDL). The Castelli I index is the most commonly used to determine CVR and is also known as the cardiac risk ratio.9 It originated from the Framingham study, whose director, Dr Castelli, observed the persistence of elevated CVR in subjects with controlled total cholesterol when associated with low HDL levels. On the other hand, the TG/HDL ratio, which has become popular in recent years as the plasma atherogenic index (PAI), in the form of log(TG/HDL), has gained a prominent role in CVR assessment, in particular in individuals with metabolic syndrome.8 In all AI, the higher the value of the ratio, the greater the CVR. Such an increase might therefore be due to an increase in the atherogenic variables contained in the numerator, a decrease in the anti-atherogenic variable in the denominator, or the sum of both.

Nevertheless, despite the abundant literature in this regard, there is still limited information on the true clinical usefulness of AIs to estimate CVR and their most suitable reference values.10,11

In recent years, some research has bolstered the role of inflammation in the aetiology and perpetuation of the atherosclerotic process,12 following the publication of several clinical trials that have illustrated the pivotal role of anti-inflammatory drugs in the prognosis of subjects with cardiovascular disease.13,14 Thus, it is clear that the lipid theory has been expanded with a broader pathophysiological approach that includes immune response factors. In this context, the introduction of standard clinical practice inflammatory parameters in the calculation of AI could improve their diagnostic and prognostic performance. Two studies have previously examined AI correlating ultra-sensitive C-reactive protein (CRP) values, as an inflammatory marker, and HDL, albeit with mixed results. While Luo et al.15 found that the CRP/HDL ratio correlated with the degree of severity of lesions in Asian patients undergoing angiography for suspected coronary artery disease, Jialal et al.,16 in an African-American population, found that the CRP/HDL ratio did not outperform the TG/HDL index as a diagnostic predictor of metabolic syndrome.

In this context, and with the aim of analysing its diagnostic performance among individuals from the Mediterranean area, we set out to evaluate a new AI in the form of a ratio relating CRP values, in this case not ultra-sensitive (in the numerator), and HDL values (in the denominator). Consequently, the higher the degree of low-grade systemic inflammation (and as a result, the higher the non-ultrasensitive CRP value), in relation to the lower HDL value (common in type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome), the higher the risk would be as estimated by this new AI.

The formula to calculate this AI was the following:

This formula was used primarily for two reasons. On the one hand, it is straightforward to calculate, in that it only includes two variables and can be estimated quickly. Secondly, the parameters of the equation (non-ultrasensitive CRP and HDL) are routinely obtained in routine laboratory tests in both primary and specialised care, in addition to which many patients are familiar with their values.

To evaluate how well the new AI performs, we studied the association of its values with the presence of carotid atherosclerosis determined by supra-aortic trunk (SAT) ultrasound in asymptomatic patients seen in the clinic for CVR assessment.

The use of SAT ultrasound is a fast, reliable, and cost-effective means by which to estimate atherosclerosis.17 Both the presence of atheromatous plaques and the increased thickness of the intima-mean complex of the arterial wall have proven useful in identifying subclinical arteriosclerosis.18 While other techniques, such as coronary computed tomography (CT) or SAT CT, enable a more accurate diagnosis of the degree of arterial involvement, the use of SAT ultrasound is considered the gold standard for non-invasive determination of vascular damage in patients with elevated CVR (as a screening method), given its accessibility and lack of adverse effects.

Material and methodsStudy poplulationThe study included 282 patients seen at the cardiology department of the IMED Valencia hospital from May 2017 to May 2021 for CVR assessment. All participants were asymptomatic and none had a personal medical history of cardiovascular disease. All subjects underwent blood tests with lipid profile and CRP, and within a period of less than one month, a SAT ultrasound was performed to determine the presence of atheromatosis.

Clinical variablesDemographic variables and the presence of conventional cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, and hypertension were recorded. Medication in relation to these factors was also considered.

Analytical variablesA full lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and TG), glycaemic profile (glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin), and non-ultrasensitive CRP were analysed.

Atherogenic indicesTo contrast the performance of the new CRP-100/HDL ratio, its sensitivity and specificity in detecting atheromatosis in the SAT were evaluated with respect to the following AIs, extensively used in clinical practice and with sufficient scientific evidence in this regard:

- •

The Castelli I Index: the ratio of total cholesterol and HDL.

- •

The Castelli II Index: the ratio of LDL to HDL.

- •

PAI: the logarithm of the ratio of TG to HDL.

A binary regression analysis was performed to compare the diagnostic capacity of the different AIs for atheromatosis in SAT. The various AIs were evaluated as continuous quantitative variables in an initial analysis. Subsequently, the AIs were also tested, considering them as categorical variables, using the optimal cut-off points in our sample, which coincided with those accepted in the literature.19 Said cut-off values were: >4 for the Castelli I index; >3 for the Castelli II index, and >.24 for the PAI.

Imaging studyThe ultrasound scan of the SAT was carried out at the radiology department of the IMED Valencia hospital as per routine practice.20 The scan was obtained with the patient in supine decubitus with their neck in hyperextension and a rotation of 45º facing the opposite side to the side being scanned.

A high-frequency linear probe and General Electric Vivid E95 ultrasound machine (GE HealthCare, Chicago, Illinois, USA) were used.

The lumen of the SAT and its vascular wall were assessed by analysing both the thickness of the intima-mean complex and the presence of atheromatous plaques. The thickness of the intima-mean complex was measured on the posterior wall of the common carotid artery (at 1 cm from the bifurcation) and values greater than 1 mm were deemed pathological. Atheroma plaques were identified as focal parietal thickening with a diameter greater than 1.5 mm.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were expressed as absolute values and percentages, and continuous variables as means ± standard deviation. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine distribution normality.

Carotid atheromatosis (as the primary study variable) was defined as the presence of one or more atheromatous plaques on ultrasound examination of the SAT. The sample was divided into 2 groups based on the presence or absence of such atheromatous plaques in the SAT.

The ROC curve was used to estimate the value of the CRP-100/HDL index with the best diagnostic performance to predict atheromatosis in SAT, while binary regression was used to compare it with other commonly used atherogenic indices using this value as the cut-off.

Results with a P-value <.05 were regarded as significant. Version 22.0 of the IBM® SPSS® Statistics software package was run for statistical analysis.

Ethical aspectsThe study adhered to international ethical recommendations as convened in the Declaration of Helsinki and current European legislation regarding medical research, as well as current legislation with respect to the Data Protection Act: Organic Law 3/2018, dated 5 December, regarding the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

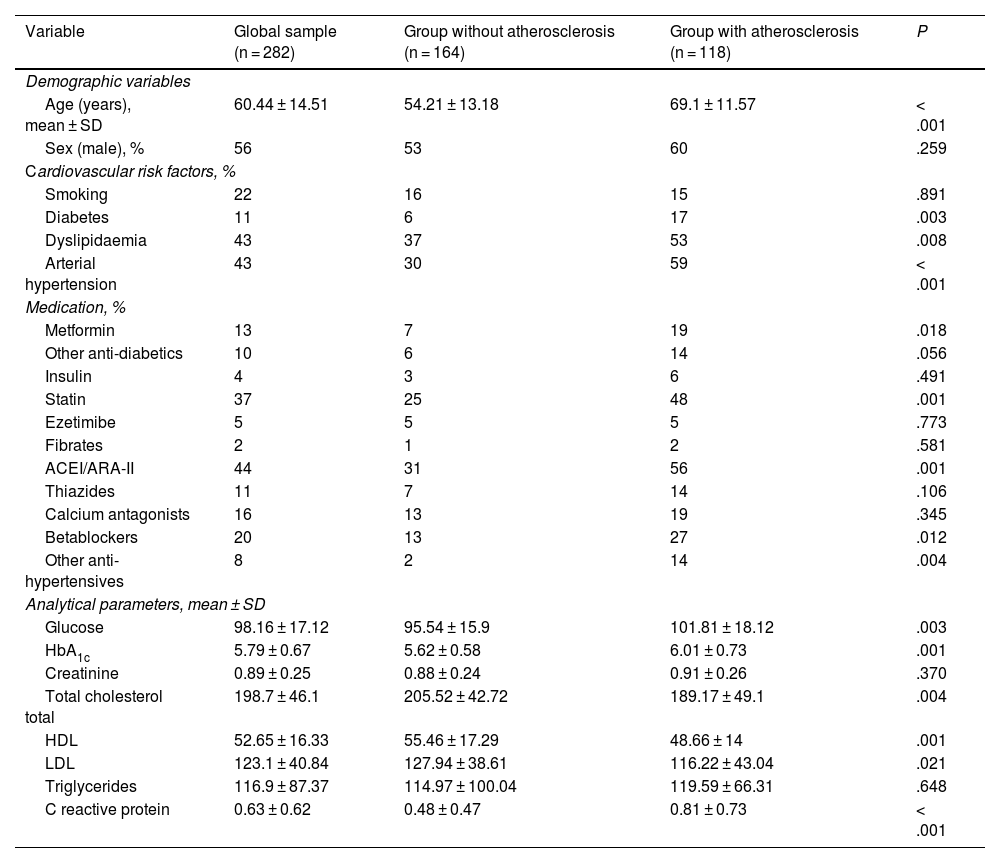

ResultsSample groups based on the presence of carotid atherosclerosisThe mean age of the 282 patients was 60.4 ± 14.5 years, with 56% of the sampele being male. When analysing the sample according to the presence or absence of atheromatous plaques in the SAT, 118 patients (41.8% of the total) were found to exhibit carotid disease. The general characteristics of both groups are displayed in Table 1.

General characteristics of the sample in terms of the presence of atherosclerosis on supra-aortic trunk ultrasound.

| Variable | Global sample (n = 282) | Group without atherosclerosis (n = 164) | Group with atherosclerosis (n = 118) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 60.44 ± 14.51 | 54.21 ± 13.18 | 69.1 ± 11.57 | < .001 |

| Sex (male), % | 56 | 53 | 60 | .259 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, % | ||||

| Smoking | 22 | 16 | 15 | .891 |

| Diabetes | 11 | 6 | 17 | .003 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 43 | 37 | 53 | .008 |

| Arterial hypertension | 43 | 30 | 59 | < .001 |

| Medication, % | ||||

| Metformin | 13 | 7 | 19 | .018 |

| Other anti-diabetics | 10 | 6 | 14 | .056 |

| Insulin | 4 | 3 | 6 | .491 |

| Statin | 37 | 25 | 48 | .001 |

| Ezetimibe | 5 | 5 | 5 | .773 |

| Fibrates | 2 | 1 | 2 | .581 |

| ACEI/ARA-II | 44 | 31 | 56 | .001 |

| Thiazides | 11 | 7 | 14 | .106 |

| Calcium antagonists | 16 | 13 | 19 | .345 |

| Betablockers | 20 | 13 | 27 | .012 |

| Other anti-hypertensives | 8 | 2 | 14 | .004 |

| Analytical parameters, mean ± SD | ||||

| Glucose | 98.16 ± 17.12 | 95.54 ± 15.9 | 101.81 ± 18.12 | .003 |

| HbA1c | 5.79 ± 0.67 | 5.62 ± 0.58 | 6.01 ± 0.73 | .001 |

| Creatinine | 0.89 ± 0.25 | 0.88 ± 0.24 | 0.91 ± 0.26 | .370 |

| Total cholesterol total | 198.7 ± 46.1 | 205.52 ± 42.72 | 189.17 ± 49.1 | .004 |

| HDL | 52.65 ± 16.33 | 55.46 ± 17.29 | 48.66 ± 14 | .001 |

| LDL | 123.1 ± 40.84 | 127.94 ± 38.61 | 116.22 ± 43.04 | .021 |

| Triglycerides | 116.9 ± 87.37 | 114.97 ± 100.04 | 119.59 ± 66.31 | .648 |

| C reactive protein | 0.63 ± 0.62 | 0.48 ± 0.47 | 0.81 ± 0.73 | < .001 |

Significant if P < .05.

ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARA-II: angiotensin II receptor antagonists; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL: high-density lipoproteins; LDL: low-density lipoproteins; SD: standard deviation.

The group of subjects who had atheromatosis in the SAT were older (69.1 ± 11.6 vs. 54.2 ± 13.2 years, P < .001) and had a higher prevalence of diabetes (17 vs. 6%, P = .003), dyslipidaemia (53 vs. 37%, P = .008), and hypertension (59 vs. 30%, P < .001). No differences were observed in relation to smoking.

Consistent with a higher prevalence of CVR factors, the use of antidiabetic drugs such as metformin, lipid-lowering drugs such as statins, and most antihypertensive drugs was significantly higher in the group of patients with atheromatosis.

On examination of analytical parameters, higher basal glucose (101.8 ± 18.1 vs. 95.5 ± 15.9 mg/dL, P = .003), glycosylated haemoglobin (6.01 ± .7 vs. 5.62 ± .6%, P = .001), and CRP (.81 ± .73 vs. .48 ± .47 mg/dL, P < .001) were also observed among these individuals. HDL values were lower in this group (48.7 ± 14.0 vs. 55.4 ± 17.3 mg/dL, P = .001). However, there was no difference regarding TG values (69.1 ± 11.6 vs. 54.2 ± 13.2 mg/dL, P = .64). Interestingly, and very likely due to the higher prevalence of statin use in the group of participants with atheromatosis, total cholesterol and LDL values were lower (189.2 ± 49.1 vs. 205.5 ± 42.7 mg/dL, P = .004, and 116.2 ± 43.0 vs. 127.9 ± 38.7 mg/dL, P = .021, respectively).

Estimation of the optimal cut-off point of the new index to estimate the risk of carotid atheromatosisThe ROC curve determined that the optimal cut-off point to estimate an increased risk of atheromatosis with the new index was a value above .92. Given that the sensitivity and specificity values were very similar with a value of 1, this was used to make comparisons.

Fig. 1 illustrates the ROC curves and areas under the curve for the four AIs analysed in the study. The CRP-100/HDL ratio demonstrated the best association with the presence of atheromatous plaques in the SAT, with an area of .678 (for a 95% confidence interval [95% CI] of .60–.75, with a P value of <.001).

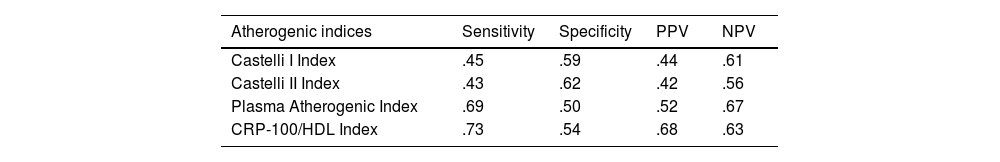

Diagnostic performance of the different atherogenic indicesWhen evaluating the performance of each AI for the detection of carotid atheromatosis, we found that the CRP-100/HDL ratio yielded the highest values for sensitivity and positive predictive value (.73 and .68, respectively), and was the AI that had the best diagnostic profile overall (Table 2).

Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the various atherogenic indices.

| Atherogenic indices | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castelli I Index | .45 | .59 | .44 | .61 |

| Castelli II Index | .43 | .62 | .42 | .56 |

| Plasma Atherogenic Index | .69 | .50 | .52 | .67 |

| CRP-100/HDL Index | .73 | .54 | .68 | .63 |

CRP: C-reactive protein; HDL: high-density lipoproteins, NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value.

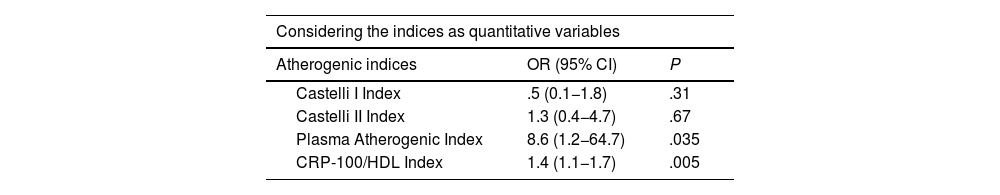

For the purposes of analysis, all AIs were used as both quantitative and categorical variables, in this case considering the previously stated cut-off points for risk: Castelli I index > 4; Castelli II index > 3; PAI > .24, and CRP-100/HDL index > 1 (Table 3).

Prediction of carotid atheromatosis using the various atherogenic indices.

| Considering the indices as quantitative variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Atherogenic indices | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Castelli I Index | .5 (0.1−1.8) | .31 |

| Castelli II Index | 1.3 (0.4−4.7) | .67 |

| Plasma Atherogenic Index | 8.6 (1.2−64.7) | .035 |

| CRP-100/HDL Index | 1.4 (1.1−1.7) | .005 |

| Considering the indices as categorical variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Atherogenic indices | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Castelli I Index > 4 | .9 (.4−2.5) | .94 |

| Castelli II Index > 3 | .9 (.3−2.3) | .91 |

| Plasma Atherogenic Index > 0.24 | 1.7 (.9−3.4) | .11 |

| CRP-100/HDL Index > 1 | 2.9 (1.5−5.5) | < .001 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; HDL: high-density lipoproteins; LDL: low-density lipoproteins; OR: odds ratio; PCR: C reactive protein; TG: triglycerides.

When comparing the various AIs using binary regression with a 95% CI, the new CRP-100/HDL ratio was the only predictor of carotid atheromatosis when considering its values both quantitatively and categorically, with an odds ratio of 1.4 (95% CI 1.1−1.7, P = .005) and an odds ratio of 2.9 (95% CI 1.5−5.5, P < .001). Castelli indices failed to exhibit a significant association with the presence of atheromatosis in the SAT, and the plasma atherogenic index only when considered as a quantitative variable (OR 8.6 [95% CI 1.2−64.7]; P = .035).

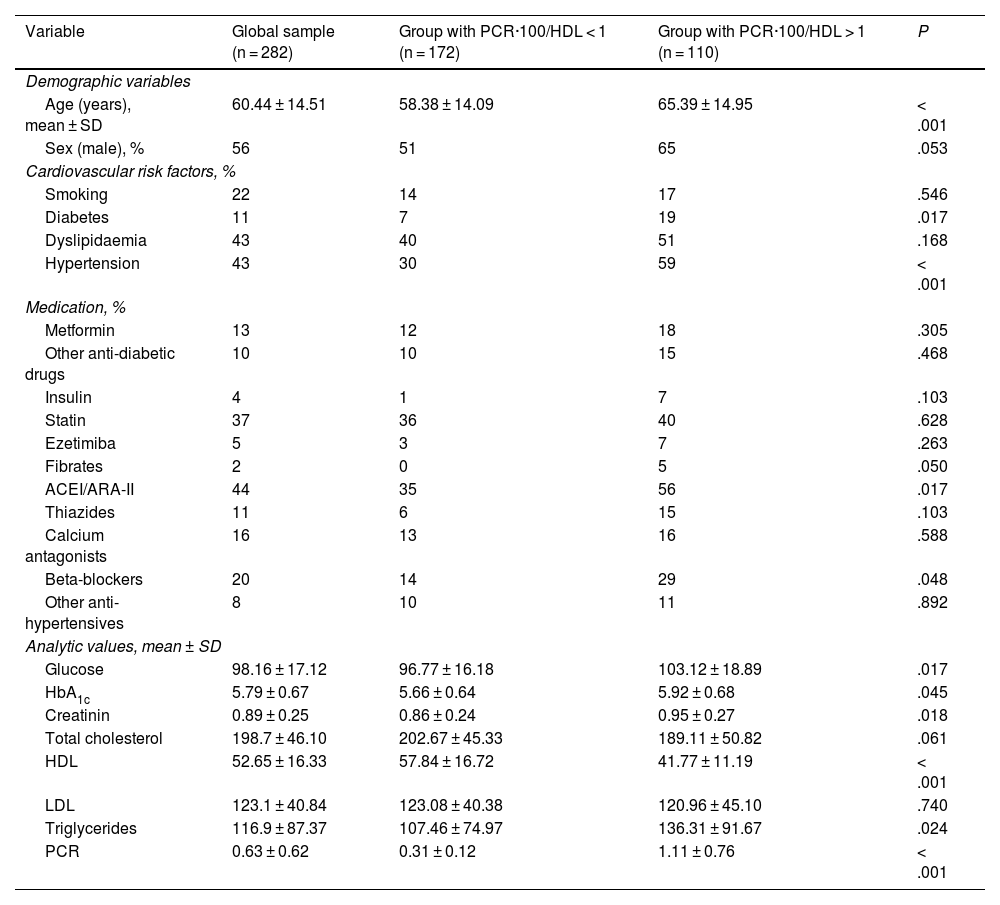

Sample groups based on the PCR·100/HDL ratioThe characteristics of the sample on the basis of the CRP-100/HDL ratio (cut-off point = 1) are illustrated in Table 4. Subjects with a ratio ≥1 were older (65.4 ± 14.9 vs. 58.4 ± 14.1 years, P < .001) and had a higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. Significantly lower HDL and higher TG and CRP values were detected, albeit no differences were noted with regard to total cholesterol and LDL values. In this case, statin use was similar in both groups (40% vs. 36%, P = .62).

General characteristics of the sample based on PCR-100/HDL ratio.

| Variable | Global sample (n = 282) | Group with PCR·100/HDL < 1 (n = 172) | Group with PCR·100/HDL > 1 (n = 110) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 60.44 ± 14.51 | 58.38 ± 14.09 | 65.39 ± 14.95 | < .001 |

| Sex (male), % | 56 | 51 | 65 | .053 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, % | ||||

| Smoking | 22 | 14 | 17 | .546 |

| Diabetes | 11 | 7 | 19 | .017 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 43 | 40 | 51 | .168 |

| Hypertension | 43 | 30 | 59 | < .001 |

| Medication, % | ||||

| Metformin | 13 | 12 | 18 | .305 |

| Other anti-diabetic drugs | 10 | 10 | 15 | .468 |

| Insulin | 4 | 1 | 7 | .103 |

| Statin | 37 | 36 | 40 | .628 |

| Ezetimiba | 5 | 3 | 7 | .263 |

| Fibrates | 2 | 0 | 5 | .050 |

| ACEI/ARA-II | 44 | 35 | 56 | .017 |

| Thiazides | 11 | 6 | 15 | .103 |

| Calcium antagonists | 16 | 13 | 16 | .588 |

| Beta-blockers | 20 | 14 | 29 | .048 |

| Other anti-hypertensives | 8 | 10 | 11 | .892 |

| Analytic values, mean ± SD | ||||

| Glucose | 98.16 ± 17.12 | 96.77 ± 16.18 | 103.12 ± 18.89 | .017 |

| HbA1c | 5.79 ± 0.67 | 5.66 ± 0.64 | 5.92 ± 0.68 | .045 |

| Creatinin | 0.89 ± 0.25 | 0.86 ± 0.24 | 0.95 ± 0.27 | .018 |

| Total cholesterol | 198.7 ± 46.10 | 202.67 ± 45.33 | 189.11 ± 50.82 | .061 |

| HDL | 52.65 ± 16.33 | 57.84 ± 16.72 | 41.77 ± 11.19 | < .001 |

| LDL | 123.1 ± 40.84 | 123.08 ± 40.38 | 120.96 ± 45.10 | .740 |

| Triglycerides | 116.9 ± 87.37 | 107.46 ± 74.97 | 136.31 ± 91.67 | .024 |

| PCR | 0.63 ± 0.62 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 1.11 ± 0.76 | < .001 |

Significant if P < .05.

ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARA-II: angiotensin II receptor antagonists; CRP: C-reactive protein; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoproteins; SD: standard deviation.

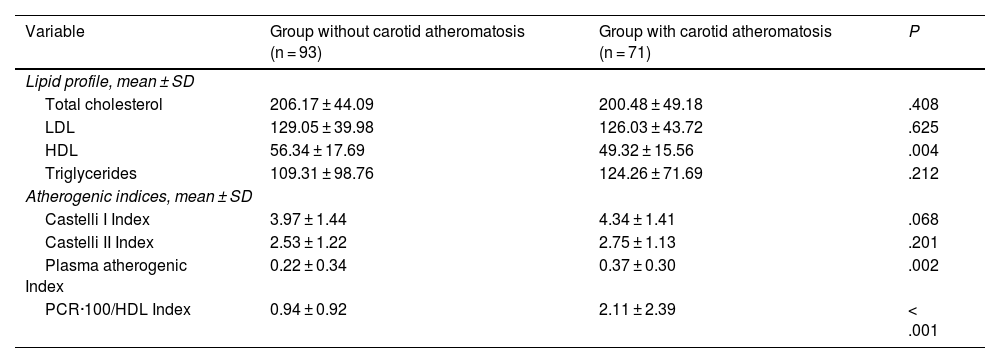

With the aim of determining whether statin use was a confounding factor in overestimating the performance of the new CRP-100/HDL index (since total cholesterol and LDL are pharmacologically lowered in individuals receiving statin therapy), the lipid profile and AI were studied in the subgroup of patients not taking statins (164 participants [58.1% of the total]).

In these subjects, total cholesterol, LDL, and TG values were similar whether or not atheromatosis was present in the SAT, with differences only with respect to HDL values (49.3 ± 15.5 vs. 56.3 ± 17.7; P = .004) (Table 5).

Characteristics of patients not taking statins.

| Variable | Group without carotid atheromatosis (n = 93) | Group with carotid atheromatosis (n = 71) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid profile, mean ± SD | |||

| Total cholesterol | 206.17 ± 44.09 | 200.48 ± 49.18 | .408 |

| LDL | 129.05 ± 39.98 | 126.03 ± 43.72 | .625 |

| HDL | 56.34 ± 17.69 | 49.32 ± 15.56 | .004 |

| Triglycerides | 109.31 ± 98.76 | 124.26 ± 71.69 | .212 |

| Atherogenic indices, mean ± SD | |||

| Castelli I Index | 3.97 ± 1.44 | 4.34 ± 1.41 | .068 |

| Castelli II Index | 2.53 ± 1.22 | 2.75 ± 1.13 | .201 |

| Plasma atherogenic Index | 0.22 ± 0.34 | 0.37 ± 0.30 | .002 |

| PCR·100/HDL Index | 0.94 ± 0.92 | 2.11 ± 2.39 | < .001 |

Significant if P < .05.

CRP: C-reactive protein; HDL: high-density lipoproteins; LDL: low-density lipoproteins; SD: standard deviation.

As for the value of the different AIs, the PAI (.37 ± .29 vs. .22 ± .34; P = .002) and the CRP-100/HDL ratio (2.11 ± 2.39 vs. .93 ± 0.92; P < .001) values correlated significantly with the presence of carotid atherosclerotic disease. The value of the Castelli indices was similar in both groups.

When comparing all four AIs in this subgroup by binary regression, the OR values were similar to those obtained in the global sample: Castelli I, OR .89 (95% CI .18–4.36; P = .89); Castelli II, OR .87 (95% CI .18–4.18; P = .89); PAI, OR 5.9 (95% CI .53–66.5; P = 0.147), and CRP-100/HDL ratio, OR 1.59 (95% CI 1.13–2.22; P = .07). Thus, the association with atheromatosis in the SAT was significant only in the case of the PAI and the new CRP-100/HDL ratio.

DiscussionIn this study of asymptomatic subjects from the Mediterranean area with a CVR assessment and no prior cardiovascular history, the CRP-100/HDL index was found to be the only predictor of carotid atheromatosis in the SAT compared to classical AIs such as the Castelli I and II, and even compared to the PAI, which has exhibited strong evidence in recent years, particularly among individuals with metabolic syndrome. The new CRP-100/HDL index was significantly associated with carotid atheromatous plaques both when considering its values continuously (in this case, the PAI did as well) and categorically, with a cut-off point rounded to 1 for easy estimation.

It is a well-known fact that CVR can be predicted in part by lipoprotein and total cholesterol concentrations, based on the fact that alterations in lipid metabolism are a major risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis and, according to some studies, account for up to 50% of the attributable risk for cardiovascular disease.21 For this reason, clinical practice guidelines continue to focus their efforts on controlling dyslipidaemia, although this is still done largely by analysing LDL and total cholesterol target figures. Other parameters, such as HDL or TG, are assumed to be variables such as non-HDL cholesterol, which, for the time being, still do not have specific treatment targets.22

However, there is a growing body of evidence regarding the residual risk derived from the entire non-HDL fraction and remaining cholesterol.23 This is due to the fact that those lipoproteins that are rich in TG, especially VLDL, are also capable of promoting and maintaining the chronic processof atherosclerosis, a situation that occurs predominantly in people with metabolic syndrome and hypertriglyceridaemia. The sum, therefore, of LDL and VLDL, which would correspond to non-HDL cholesterol (if we add the small proportion of its remnants and lipoprotein A), could be an excellent indicator of atherogenic cholesterol and should be a therapeutic target in the next update of clinical guidelines.

In the same vein, a decrease in «anti-atherogenic» cholesterol, i.e., HDL cholesterol, could be identified as a CVR factor even in patients with LDL levels at therapeutic target levels.24 The trend in CVR analysis in recent years has therefore been to combine both effects (atherogenic vs. anti-atherogenic) with the aim of providing a more complete CVR assessment. In this context, the use of AIs that are formulated by using atherogenic and antiatherogenic variables is regarded as having diagnostic and prognostic value. Their application would thereby constitute a straightforward tool with which to quantify the concentrations of lipid fractions by weighing the opposing relationship between some of them and, as a result, make it possible to assess the person's CVR more comprehensively. Despite the aforementioned, current recommendations do not yet include the use of AI consistently, or do so with a low level of recommendation.25,26

Given the foregoing, one way to approach the situation of low-grade inflammation as part of the atherosclerosis process would be to include inflammatory variables in the equation, which would broaden the patient's CVR spectrum.27 We therefore set out to include a commonly used variable such as non-ultrasensitive CRP, available to all healthcare professionals and to patients themselves, in order to devise a new formula for CVR. Using a «rounded» cut-off point that is easy to remember and apply, we found that subjects with a value above 1 exhibited a positive association with atheromatosis in the SAT, with a sensitivity of more than 70% and positive and negative predictive values exceeding 60%, which would make it an outstanding screening tool. In our population, the CRP-100/HDL ratio was proven to be the AI that had the best diagnostic performance and was the only predictor of atheromatosis when considering both quantitative (continuous) and categorical (with an optimal cut-off point) AI values.

CRP values were clearly related to CVR more than 2 decades ago,28–30 and even more so after the publication of the JUPITER31 study in 2008, which was a revolution in the world of clinical cardiology. In this clinical trial, participants with good lipid control, as determined by LDL values of less than 130 mg/dL but with mildly elevated ultra-sensitive CRP values (above 2.0 mg/L), were randomised to receive either rosuvastatin or placebo and monitored until a first major cardiovascular event (myocardial infarction, stroke, angina, cardiovascular death). The study was prematurely terminated because of the increase in events in the placebo group. It was concluded that apparently healthy subjects, without dyslipidaemia but with mildly elevated CRP, benefited from taking statins by reducing the incidence of major cardiovascular events.

Other studies, such as the CANTOS13 trial, which evaluated the role of canakinumab (a selective interleukin 1-beta inhibitor) in reducing major cardiovascular events, or the COLCOT14 trial, which explored the role of colchicine treatment following acute myocardial infarction, have further reinforced the role of the immune response in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. In this context, the inclusion of an inflammatory variable in the CRP-100/HDL AI would be especially valuable in the current context, for two main reasons. On the one hand, because of the growing population being treated with statins, which present pharmacological decreases in LDL levels and, therefore, could detract from the value of classical AIs such as the Castelli I and II. On the other hand, the number of people with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome has grown exponentially in recent years.32 In these cases, low grade inflammation, decreased HDL, and increased TG are constant, such that including these metabolic disturbances in the AI would be critical to defining the new ratio.

The CRP-100/HDL ratio is therefore a new AI with a certain transgressive nature, inasmuch as it does not include traditional lipid profile parameters such as total cholesterol, LDL, or TG. However, it does combine two physiopathological situations that are common in many patients nowadays: chronic, low-grade inflammation related to metabolic disorders, and low HDL values, frequently found in patients with type 2 diabetes. Both determinants, made all the stronger in an easily calculated ratio, make it possible to detect subclinical atheromatosis in the SAT of patients at high cardiovascular risk with a higher yield compared to other AIs.

LimitationsImportant limitations of the study are the small sample size, its single-centre scope, and the data analysis (an observational analytical study). The evaluation of results based on anonymised data collection, with variables that come from routine clinical practice and not from a pre-established protocol, could potentially promote the appearance of biases due to the heterogeneity of the sample and the procedures.

On the other hand, the calculation of the CRP-100/HDL ratio could be limited in those patients for whom the non-ultrasensitive CRP value was not quantified given that it was within the normal range, as is the case in some centres.

The present study was conducted as a referral cohort and, therefore, the results observed would have to be verified in a second validation cohort.

ConclusionsThe new CRP-100/HDL index revealed the best diagnostic performance for the detection of carotid atheromatosis compared to other traditional AIs in a Spanish population of asymptomatic patients with no past cardiovascular history.

The following secondary findings were also considered:

- •

There was a high prevalence of carotid atheromatosis (>40%) in this sample of patients from the Mediterranean area.

- •

The most common risk factors were arterial hypertension and dyslipaemia (43% in both cases).

- •

The PCR·100/HDL index was an independent predictor of carotid atheromatosis, regardless of statis treatment.

None.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.