Fibrates are a group of drugs that are known mainly for reducing triglycerides, increasing high density lipoproteins (HDL), and reducing the fraction of small, dense LDL particles. The results of a Cochrane Collaboration study have recently been published on their efficacy and safety in the secondary prevention of severe cardiovascular accidents, including coronary and cerebrovascular disease.

The study included randomised clinical trials in which the fibrate was compared with placebo or with no treatment. Clinical trials comparing two different fibrates were excluded.

The clinical trials evaluated included a total of 16,112 patients (13 trials). The meta-analysis (including all the trials with fibrates) showed evidence of a protective effect of the fibrates compared with placebo as regards a compound objective of non-fatal stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and death of cardiovascular origin (hazard ration of 0.88, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.83–0.94; in 16,064 individuals included in 12 studies). Thus, the results showed, with a moderate level of evidence, that fibrates could be effective in secondary prevention considering a compound objective of non-fatal stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and death of cardiovascular origin.

Los fibratos son un grupo de fármacos que se caracterizan principalmente por reducir los triglicéridos, elevar las lipoproteínas de alta densidad (HDL) y reducir la fracción de partículas de LDL pequeñas y densas. Se ha publicado recientemente los resultados de un estudio de la Colaboración Cochrane sobre su eficacia y seguridad en la prevención secundaria de accidentes cardiovasculares graves, incluyendo enfermedad coronaria y cerebrovascular.

El estudio incluye ensayos clínicos aleatorizados en los que el fibrato se compara con placebo o con no tratamiento. Se excluyen ensayos clínicos comparando 2 fibratos diferentes.

Los ensayos clínicos evaluados incluyen un total de 16.112 pacientes (13 ensayos). El metaanálisis (incluyendo todos los ensayos con fibratos) muestra la evidencia de un efecto protector de los fibratos comparados con placebo en lo relativo a un objetivo compuesto de ictus no fatal, infarto de miocardio no fatal, y muerte de origen cardiovascular (tasa de riesgo de 0,88, con intervalo de confianza (95%) de 0,83 a 0,94; en 16.064 individuos incluidos en 12 estudios). Por tanto, los resultados muestran con una evidencia de grado moderado que los fibratos pueden ser efectivos en la prevención secundaria considerando un objetivo compuesto de ictus no fatal, infarto no fatal, y muerte de origen cardiovascular.

Fibrates are drugs with the fundamental effects of reducing the abnormalities characterising a specific group of dyslipidaemias. This pharmacological group includes: clofibrate, gemfibrozil, bezafibrate, ciprofibrate and fenofibrate; although, currently, the most used drugs in practice are fenofibrate and gemfibrozil, due to their effects and the capacity of the former to be combined safely in polymedicated patients, and particularly in treatments combined with statins.

Consequently, fibrates have been used in the treatment of certain dyslipidaemias, primarily and fundamentally those characterised by increased triglycerides with or without a decrease in cHDL, either primary or secondary to very prevalent processes such as diabetes mellitus type 2, visceral obesity or metabolic syndrome. The paradigm of these dyslipidaemias is that known as atherogenic dyslipidaemia, in which the three basic characteristics outlined above converge: hypertriglyceridaemia, low cHDL, and presence of a large proportion of small, dense LDL particles.

The significance of this type of dyslipidaemia is that we know accurately that it is a decisive component of the residual cardiovascular risk of lipid origin once the cLDL levels are under control. Therefore, detection and treatment of atherogenic dyslipidaemia seems essential if lipid alterations are present; and especially in patients who present a high cardiovascular risk or who have had previous clinical manifestations of cardiovascular disease (secondary prevention), in whom strict control of each and every one of the risk factors becomes imperative.

A response to this interest in determining the clinical benefits of fibrates in secondary prevention has been provided in a systematic review by the Cochrane Collaboration which was published with the meta-analysis of 13 clinical trials, which included 16,112 individuals.1 Eleven of the trials refer to patients with a history of coronary heart disease, two refer to patients with a history of cerebrovascular disease; one of the trials refers to patients with a history of both. The study refers to the effects of fibrates with regard to the placebo, and the results on coronary episodes (fatal and non-fatal) and cerebrovascular episodes (fatal and non-fatal), as well as mortality (vascular and all-cause mortality) are analysed.

ReviewEpidemiological studies have shown unequivocally that the increase in triglycerides and the decrease in cHDL are associated significantly with an increase in cardiovascular risk.2–4 In addition, these lipid factors are responsible for a residual risk in patients treated with statins, in whom the statin does not prevent the cardiovascular risk associated with hypertriglyceridaemia or the decrease in cHDL.5,6

Fibrates, which have been used for decades, have proven to be effective in the prevention of cardiovascular accidents, but their benefit in cardiovascular prevention as a whole has been a matter of controversy. A recent meta-analysis7 made it very clear that they are useful for the prevention of cardiovascular accidents, but their role in primary or secondary prevention is not properly clarified.

In fact, and considering only secondary prevention in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease, the results have not always been consistent, and, while some studies have shown a benefit,8,9 other studies have called this benefit into question.10,11

In the systematic review carried out by the Cochrane Collaboration, patients considered strictly as undergoing secondary prevention (history of coronary heart disease or cerebrovascular disease) were included regardless of their initial lipid profile or their previous treatment. High-risk patients who have not presented with a previous clinical disease were not included (due to the fact that they suffer intense or associated risk factors). The comparator was the placebo, and never statins, which may be part of the treatment (although only in some studies), but in both arms (in order to exclude the effect derived from the reduction in cholesterol).

The primary objective consisting of non-fatal infarction or stroke and death of vascular origin has been assessed. In addition, secondary objectives have been assessed: infarction (fatal or non-fatal), stroke (fatal or non-fatal), death of vascular origin or death by any cause.

The influence of other variables has also been evaluated, mainly: age; gender; presence/absence of diabetes mellitus type 2; and type of previous cardiovascular disease.

Thirteen assessable clinical trials were included because it was possible to assess the results in order to meet the objectives.10,12–23 Some very important studies were excluded from the analysis for various reasons: some focussed on primary prevention24–27; some on primary and secondary prevention, making it difficult to extrapolate the results of the latter11,28,29; and others because they did not identify clinical outcomes.30,31 Trials in which clofibrate, gemfibrozil, bezafibrate and fenofibrate were used were included.

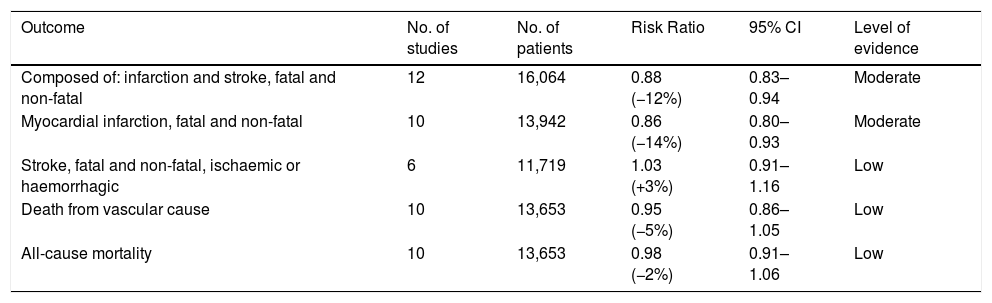

ResultsCardiovascular benefits- •

Non-fatal infarction and stroke and vascular mortality:

From the analysis of 12 of the studies included in the review, which comprised of more than 16,000 individuals, it can be deduced that the use of fibrates is accompanied by a significant risk reduction: RR of 0.88 with 95% CI of 0.83–0.94.

- •

Myocardial infarction, fatal and non-fatal:

Information can be collected from ten studies with approximately 14,000 individuals. In the meta-analysis of the studies, the RR turned out to be 0.86 with a 95% CI of 0.80–0.93.

- •

Fatal and non-fatal stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic):

The information comes from six clinical trials with more than 11,700 individuals, with an RR of 1.03 and a 95% CI of 0.91–1.16.

- •

Vascular mortality:

This concept includes death of cerebrovascular origin (for ischaemic or haemorrhagic reasons), due to coronary heart disease (infarction, heart failure and sudden death), due to peripheral arterial disease or other vascular causes. In ten studies, which included more than 13,600 individuals, in which it was possible to assess vascular mortality, the RR turned out to be 0.95 with a 95% CI of 0.86–1.05.

- •

All-cause mortality:

With data coming from ten trials and more than 13,600 individuals, the meta-analysis of the trials did not show any significant effect of the fibrates, with an RR of 0.98 and a 95% CI of 0.91–1.06 (Fig. 1).

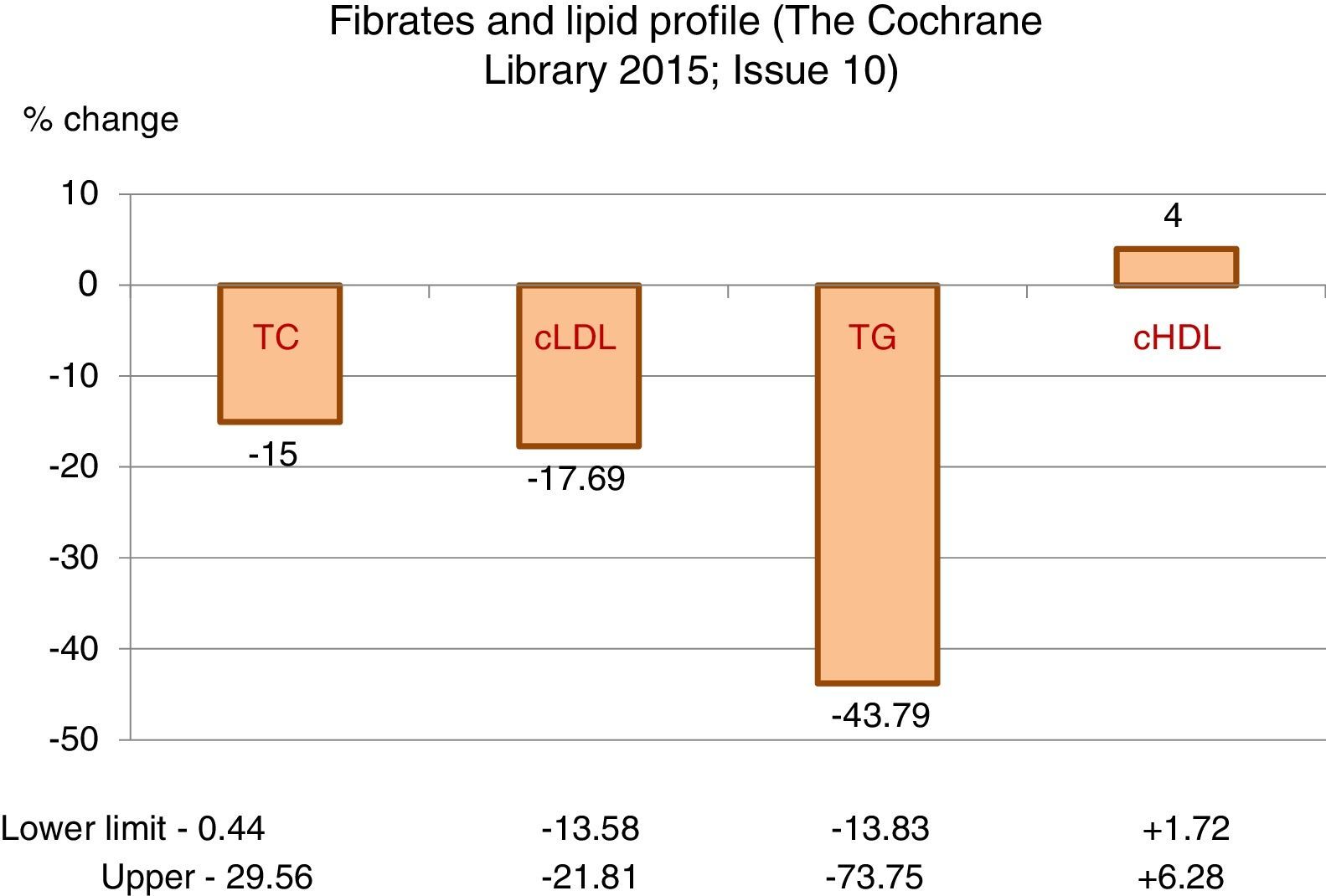

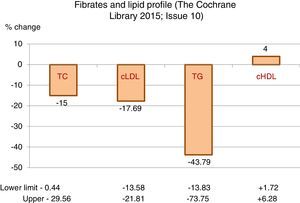

The greatest hypolipidaemic effect of fibrates is focussed on the decrease in triglycerides, with a mean reduction greater than 43%, with high variability that may exceed 70%, as the intensity of the response is influenced by the baseline figure of triglycerides.

The effect on total cholesterol and cLDL is less significant, with decreases, on average, of around 15 and 17%, respectively.

Additionally, they may induce an average increase of 4% in HDL-cholesterol, also with considerable variability (Table 1).

Fibrates and lipid profile.

| Outcome | No. of studies | No. of patients | Risk Ratio | 95% CI | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composed of: infarction and stroke, fatal and non-fatal | 12 | 16,064 | 0.88 (−12%) | 0.83–0.94 | Moderate |

| Myocardial infarction, fatal and non-fatal | 10 | 13,942 | 0.86 (−14%) | 0.80–0.93 | Moderate |

| Stroke, fatal and non-fatal, ischaemic or haemorrhagic | 6 | 11,719 | 1.03 (+3%) | 0.91–1.16 | Low |

| Death from vascular cause | 10 | 13,653 | 0.95 (−5%) | 0.86–1.05 | Low |

| All-cause mortality | 10 | 13,653 | 0.98 (−2%) | 0.91–1.06 | Low |

Source: The Cochrane Library.1

The adverse effects were rare and of little importance. The most common effects were gastrointestinal, which were indicated in six of the studies analysed, although with a borderline significance (RR: 1.02 95% CI: 1.00–1.04).

Other effects identified with a certain frequency were elevated liver enzymes (although with high variability, and particularly with gemfibrozil), or myopathy (RR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.31–2.35).

An increase in plasma creatinine was also found, especially with bezafibrate, with an RR of 5.01 (95% CI: 1.93–13.03).

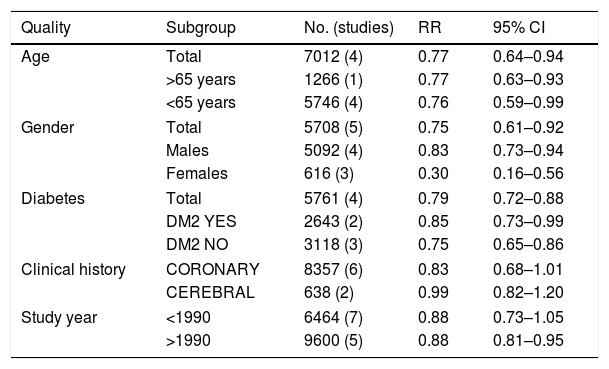

Subgroups analysed- •

Age:

The benefit observed with fibrates in the composite variable analysed is similar in individuals aged under 65 (RR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.59–0.99) or greater than this age (RR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.63–0.93).

- •

Gender:

The benefit of fibrates on the composite variable studied is also maintained, both in males (RR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.73–0.94) and in females (RR: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.16–0.56).

- •

Diabetes mellitus:

The analysis of the subgroups with or without diabetes mellitus showed that there are no differences in the benefit on outcomes in the primary objective. Consequently, there is a similar benefit in the more than 2600 diabetics included in the studies (RR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.73–0.99) and in the more than 3100 non-diabetics (RR: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.65–0.86).

- •

Previous detection of cardiovascular disease:

The protective effect of fibrates turned out to be similar in those individuals in which the clinical history was the result of coronary heart disease (RR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.68–1.01) or of cerebrovascular disease (RR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.82–1.20) (Table 2).

Benefits of fibrates in secondary prevention (infarction+stroke, fatal+non-fatal, CV death). Analysis of different subgroups.

| Quality | Subgroup | No. (studies) | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Total | 7012 (4) | 0.77 | 0.64–0.94 |

| >65 years | 1266 (1) | 0.77 | 0.63–0.93 | |

| <65 years | 5746 (4) | 0.76 | 0.59–0.99 | |

| Gender | Total | 5708 (5) | 0.75 | 0.61–0.92 |

| Males | 5092 (4) | 0.83 | 0.73–0.94 | |

| Females | 616 (3) | 0.30 | 0.16–0.56 | |

| Diabetes | Total | 5761 (4) | 0.79 | 0.72–0.88 |

| DM2 YES | 2643 (2) | 0.85 | 0.73–0.99 | |

| DM2 NO | 3118 (3) | 0.75 | 0.65–0.86 | |

| Clinical history | CORONARY | 8357 (6) | 0.83 | 0.68–1.01 |

| CEREBRAL | 638 (2) | 0.99 | 0.82–1.20 | |

| Study year | <1990 | 6464 (7) | 0.88 | 0.73–1.05 |

| >1990 | 9600 (5) | 0.88 | 0.81–0.95 | |

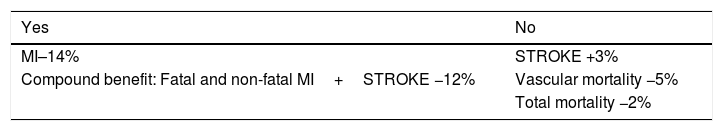

The meta-analysis, including all the clinical trials using fibrates in secondary prevention, shows that the drug has a protective effect, compared to the placebo, mainly in an objective composed of non-fatal infarction and stroke and death of vascular origin. However, using fibrates independently does not have any benefit for the prevention of strokes, for vascular mortality or total mortality (Table 3). Therefore, the primary effect of fibrates is focussed on preventing recurrences of fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction. And this efficacy is associated with safety in their use.

Clinical benefit of fibrates in secondary prevention.

| Yes | No |

|---|---|

| MI–14% | STROKE +3% |

| Compound benefit: Fatal and non-fatal MI+STROKE −12% | Vascular mortality −5% |

| Total mortality −2% |

Source: The Cochrane Library.1

These results are consistent with previously published results. Another meta-analysis7 confirmed a 10% reduction in the relative risk of increased cardiovascular accidents and a 13% reduction in coronary heart episodes, but not in cerebrovascular accidents, and coincides with the absence of differences in vascular mortality or in all-cause mortality. Finally, in another recent study,32 a 20% reduction in non-fatal infarctions was observed, with no reduction in strokes, or in mortality due to coronary heart disease (−8%).

In the FIELD study,11 although they were mainly individuals undergoing primary prevention (their analysis has not been included in this study for this reason), the sub-population undergoing secondary prevention did not show a significant reduction in cardiovascular accidents (cardiovascular death, infarction, stroke, coronary or carotid revascularisation). This was explained by the use of statins, both in the group treated with fibrate and the group treated with the placebo.

Therefore, although the use of fibrates has been a controversial matter, it is presented as useful in patients undergoing secondary prevention, especially for the prevention of both non-fatal and fatal recurrences of coronary origin. And this applies regardless of age, gender the presence or absence of diabetes, and the type of vascular territory previously affected. For this reason, and due to its effects on lipids, the majority of the recommendations promoted by scientific organisations (Table 4) include use of fibrates in cases in which (once the cLDL is under control and the measures aimed at lifestyle are optimised) elevated figures of triglycerides and atherogenic cholesterol (non-HDL cholesterol) are maintained or there is a clear atherogenic dyslipidaemia.

Recommendation of fibrates in cardiovascular prevention.

| No | Yesa |

|---|---|

| NICE, 2014 | IAS, 2014 ESC/EAS, 2016 SEA, 2017 AACE, 2017 |

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Millan J, Pintó X, Brea A, Blasco M, Hernández Mijares A, Ascaso J, et al. Los fibratos en la prevención secundaria de la enfermedad cardiovascular (infarto e ictus). Resultados de una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis de la colaboración Cochrane. Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2018;30:30–35.