Post-acute pancreatitis diabetes mellitus (PPDM-A) is a type of diabetes linked to pancreatic exocrine dysfunction, which increases the risk of pancreatic cancer and mortality. Hyperlipidemia, or high blood lipid levels, is the third leading cause of acute pancreatitis (AP) and is associated with a higher diabetes risk. However, the link between lipid-lowering treatments and PPDM-A is unclear. This study aims to explore this relationship.

MethodsA cohort of 223 patients diagnosed with AP and hyperlipidemia was categorized into PPDM-A and non-PPDM-A groups. Binary logistic regression was utilized to analyze the correlation between fibrate therapy and PPDM-A incidence. Mendelian randomization (MR) was used to determine whether there was a causal relationship between triglyceride levels and diabetes.

ResultsElevated blood glucose levels (GLU) (OR=1.360, p<0.001), female (OR=0.091, p=0.030), severity of AP [moderately severe AP (MASP) (OR=5.585, p=0.019)], recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) (OR=6.399, p=0.007), and fibrate use (OR=0.109, p=0.001) emerged as independent influencing factors of PPDM-A. MR evidence suggests a causal relationship between triglyceride levels and diabetes risk (OR=1.088, p<0.001), with a two-step MR showing that pancreatitis partially mediates this effect with a mediated proportion of 1.55% (p=0.048).

ConclusionFibrates demonstrate the potential to lower the risk of PPDM-A among individuals with AP and hypertriglyceridemia. Furthermore, the effect of triglyceride levels on diabetes risk was partly mediated by pancreatitis.

La diabetes mellitus postaguda es un tipo de diabetes relacionada con la disfunción exocrina pancreática, que aumenta el riesgo de cáncer de páncreas y de mortalidad. La hiperlipidemia, o niveles altos de lípidos en la sangre, es la tercera causa principal de pancreatitis aguda y se asocia con un mayor riesgo de diabetes. Sin embargo, la relación entre los tratamientos hipolipemiantes y la diabetes mellitus postaguda-pancreatitis mellitus no está clara. Este estudio tiene como objetivo explorar esta relación.

MétodosUna cohorte de 223 pacientes diagnosticados con pancreatitis aguda e hiperlipidemia se clasificó en los grupos de diabetes mellitus post-pancreatitis y diabetes mellitus no post-pancreatitis. Se utilizó la regresión logística binaria para analizar la correlación entre el tratamiento con fibratos y la incidencia de diabetes mellitus post-pancreatitis. Se utilizó la aleatorización mendeliana para determinar si existía una relación causal entre los niveles de triglicéridos y la diabetes.

ResultadosLos niveles elevados de glucosa en sangre (OR=1,360, p<0,001), las mujeres (OR=0,091, p=0,030), la gravedad de la pancreatitis aguda [pancreatitis aguda moderadamente grave (OR=5,585, p=0,019)], la pancreatitis aguda recurrente (OR=6,399, p=0,007) y el uso de fibratos (OR=0,109, p=0,001) emergieron como factores influyentes independientes de la pancreatitis mellitus postaguda. La evidencia de aleatorización mendeliana sugiere una relación causal entre los niveles de triglicéridos y el riesgo de diabetes (OR=1,088, p<0,001), con una aleatorización mendeliana en dos pasos que muestra que la pancreatitis media parcialmente este efecto con una proporción mediada de 1,55% (p=0,048).

ConclusiónLos fibratos demuestran el potencial de reducir el riesgo de diabetes mellitus post-pancreatitis entre las personas con pancreatitis aguda e hipertrigliceridemia. Además, el efecto de los niveles de triglicéridos sobre el riesgo de diabetes estuvo mediado en parte por la pancreatitis.

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a prevalent medical condition, affecting approximately 33.74 individuals per 100,000 population.1 Predominantly instigated by gallstone disease and alcohol abuse, AP constitutes a significant burden on global healthcare systems.2 Notably, hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) emerges as the third leading cause, contributing to about 10% of AP cases.2 Elevated triglyceride levels in the bloodstream, defined as fasting serum triglycerides of 150mg/dL (1.7mmol/L), serve as a pivotal trigger for pancreatitis, fostering the accumulation of free fatty acids and eliciting an inflammatory cascade within the pancreas.3 Severe HTG, characterized by triglyceride levels exceeding 500mg/dL, poses a substantial risk factor for pancreatitis development.4

Recent investigations have shed light on the nuanced presentation of lipogenic pancreatitis, showcasing its propensity for more severe clinical manifestations compared to non-lipogenic counterparts.5 Among individuals with hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis (HTG-AP), heightened triglyceride levels correlate with a more protracted hospitalization course, increased complication rates, prolonged stays, and elevated mortality rates.6,7

Crucially, managing hyperlipidemic acute pancreatitis hinges upon lipid-lowering interventions, with fibrates emerging as the foremost efficacious anti-hyperlipidemia agents in mitigating elevated triglyceride levels.6,8 Post-acute pancreatitis diabetes mellitus (PPDM-A) appears as a consequential metabolic sequelae, encompassing 80% of all exocrine pancreatic diabetes cases and accounting for 1.8% of adult diabetes instances.9,10 Exhibiting poor glycemic control, approximately 20.9% of PPDM-A patients necessitate insulin therapy within five years.10 Insights from existing literature suggest a discernible interplay between lipid metabolism and insulin resistance.11,12 Thus, this study elucidates the nexus between fibrates and diabetes after primary acute pancreatitis with hypertriglyceridemia, offering valuable insights into therapeutic modalities and long-term metabolic outcomes. Since it's very challenging to find the specific genetic marker SNP for PPDM-A in the Mendelian database, we decided to investigate the connection between lipid-lowering medications and PPDM-A from a different angle. We were curious to see if these drugs could reduce the risk of PPDM-A by lowering the chances of pancreatitis. Therefore, we used Mendelian randomization (MR) methods to determine whether there is a causal relationship between triglycerides and diabetes, and if so, two-step MR to determine whether pancreatitis partially mediates the effects.

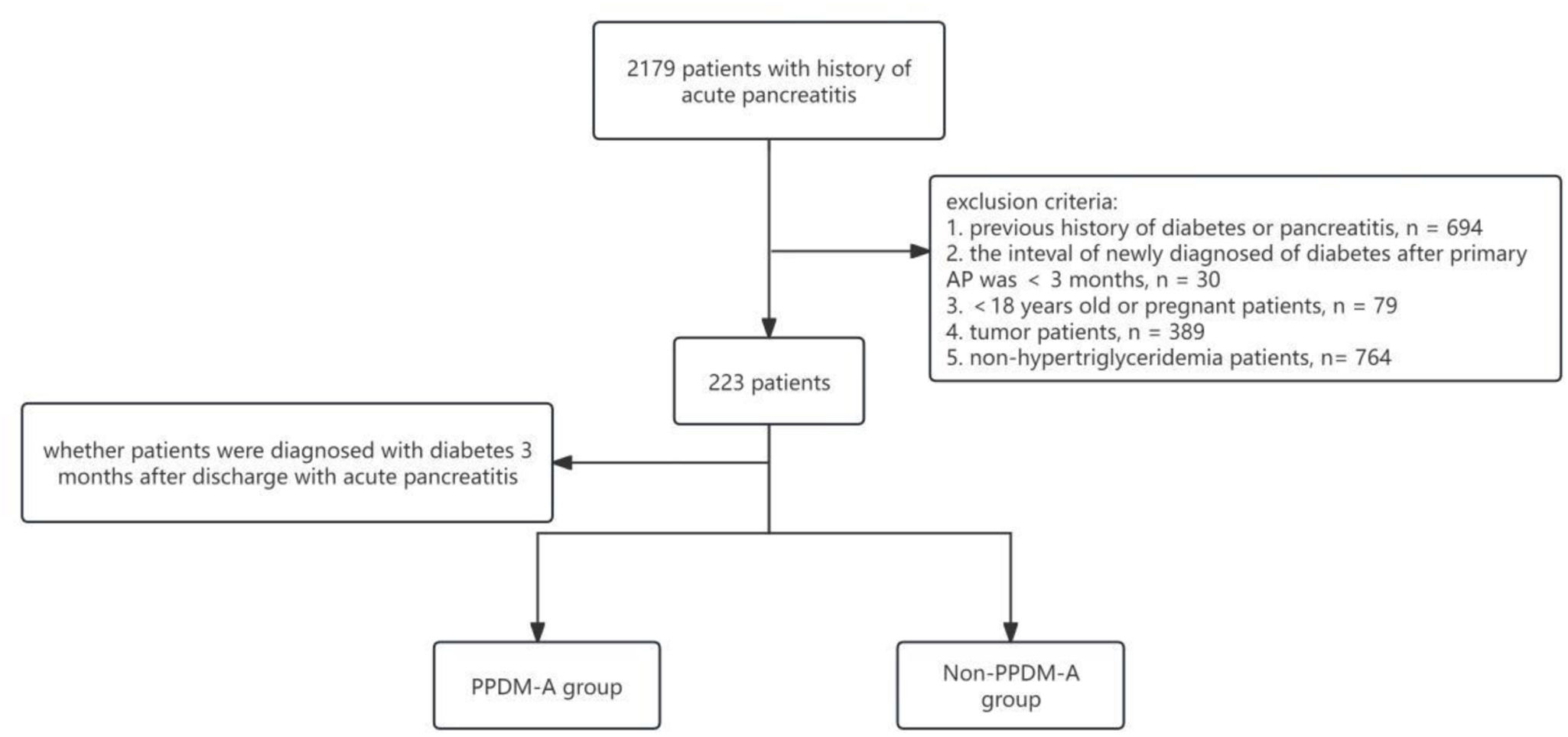

MethodsPatient selectionThis study was conducted at the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University from July 2013 to January 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with acute pancreatitis; (2) patients with hypertriglyceridemia. Exclusion criteria included: (1) a history of diabetes or previous episodes of pancreatitis; (2) alcoholic or biliary pancreatitis; (3) individuals under 18 years of age or pregnant; (4) the presence of tumors; (5) subjects lacking essential clinical data. A total of 223 patients were enrolled. Participants with acute pancreatitis were further classified into two groups based on the development of diabetes within three months post-discharge: the PPDM-A group and the non-PPDM-A group (Fig. 1).

Data collectionBasic patient demographics and clinical parameters were extracted from the hospital's electronic medical records system. Data included gender, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, alcohol consumption history, presence of fatty liver disease (FLD), white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils (NEU), C-reactive protein (CRP), levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), uric acid (UA), fasting cholesterol (TC), fasting triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), admission blood glucose (GLU), calcium (Ca), blood amylase (AMY), pancreatitis severity grading, history of recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP), and utilization of lipid-lowering medications (fibrates) as initial therapy. This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University with batch number KY2023253.

Definitions- (1)

Acute pancreatitis: Diagnosis criteria include meeting at least two of the following: persistent abdominal pain, serum amylase and/or lipase levels exceeding three times the upper limit of normal, or abdominal imaging revealing characteristic findings. Severity grading includes moderately acute pancreatitis (MAP), moderately severe acute pancreatitis (MSAP), severe acute pancreatitis (SAP), and critical acute pancreatitis (CAP).13

- (2)

Hypertriglyceridemia: Defined as serum triglyceride levels≥1.7mmol/L. Mild hyperlipidemia falls within the range of 1.7–11.4mmol/L, while severe hyperlipidemia surpasses 11.4mmol/L.14

- (3)

PPDM-A: Refers to diabetes onset occurring at least three months post-initial acute pancreatitis episode in individuals without prior diabetic history.

Data analysis was conducted using R version 4.4.2 and RStudio statistical software. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the data. For continuous variables that followed a normal distribution, the results are presented as the mean±standard deviation (x±s). For continuous variables that did not follow a normal distribution, the results are expressed as the median with the interquartile range [M (P25, P75)]. The “CBCgrps” package in RStudio was utilized to compare the two groups.

Additionally, binary logistic regression analysis was employed to investigate the association between lipid-lowering therapy and the development of PPDM-A. A significance level of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Mendelian randomization data sourcesExposure dataIn our study, we selected SNPs associated with triglyceride levels as instrumental variables. The SNP data from GWAS (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/), GWAS ID is ebi - a - GCST90092954. Finally, we included 16S rRNA gene sequencing data from 115,082 samples from the European population.

Results informationWe selected SNPs related to diabetes as instrumental variables from pooled GWAS statistics, which included 35,840 cases and 118,862 controls (GWAS ID: ukb-a-488).

Genetic instrumental variables for a potential mediatorWe obtained SNP data associated with pancreatitis (GWAS IDs: finn-b-ALCOPANCACU) from public GWASs, which included 218,792 participants of European descent.

Mendelian randomizationWe employed three highly effective and widely used Mendelian randomization (MR) techniques to explore the potential causal relationship between triglycerides and diabetes. These techniques include the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method, MR-Egger regression, and the weighted median method. The IVW method serves as the primary approach in MR analysis and is utilized to infer causality. MR-Egger regression assesses whether the instrumental variables exhibit horizontal pleiotropy.

In this study, we utilized R software version 4.2.2 along with the “TwoSampleMR” R package for the statistical analysis of all Mendelian randomization (MR) assessments. We employed a two-step MR approach to investigate the potential mediating role of pancreatitis between triglycerides and diabetes. Initially, we estimated the direct effect of genetically predicted triglycerides on diabetes using univariate Mendelian randomization (UVMR) to determine the overall association between these two variables. Following this, we applied a two-sample MR to estimate the impact of triglycerides on pancreatitis. Additionally, we evaluated the effect of pancreatitis on diabetes using the two-sample MR method. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of a potential association.

To evaluate the mediating role of pancreatitis, we calculated the product of the estimated effect of triglycerides on pancreatitis and the estimated effect of pancreatitis on diabetes. This gave us the pancreatitis-mediated effect. Next, we divided this mediating effect by the total effect of triglycerides on diabetes to determine the mediating ratio, which revealed the potential impact of triglycerides on diabetes.

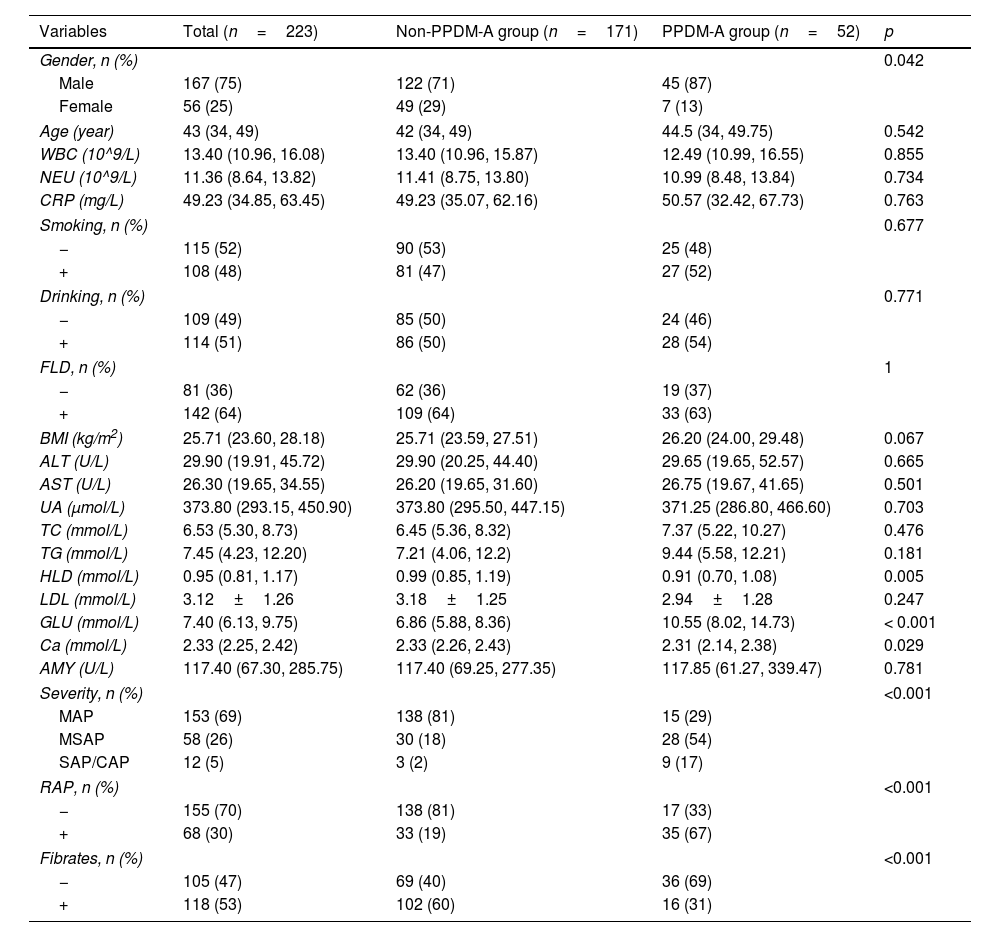

ResultsBaseline characteristics of patientsThe study included 223 patients diagnosed with pancreatitis caused by hyperlipidemia. Among these patients, 52 developed PPDM-A, leading to an incidence rate of approximately 23.3%. Significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of gender, HDL, GLU, Ca, severity of pancreatitis, RAP, and the use of fibrates, as shown in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Variables | Total (n=223) | Non-PPDM-A group (n=171) | PPDM-A group (n=52) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | 0.042 | |||

| Male | 167 (75) | 122 (71) | 45 (87) | |

| Female | 56 (25) | 49 (29) | 7 (13) | |

| Age (year) | 43 (34, 49) | 42 (34, 49) | 44.5 (34, 49.75) | 0.542 |

| WBC (10^9/L) | 13.40 (10.96, 16.08) | 13.40 (10.96, 15.87) | 12.49 (10.99, 16.55) | 0.855 |

| NEU (10^9/L) | 11.36 (8.64, 13.82) | 11.41 (8.75, 13.80) | 10.99 (8.48, 13.84) | 0.734 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 49.23 (34.85, 63.45) | 49.23 (35.07, 62.16) | 50.57 (32.42, 67.73) | 0.763 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.677 | |||

| − | 115 (52) | 90 (53) | 25 (48) | |

| + | 108 (48) | 81 (47) | 27 (52) | |

| Drinking, n (%) | 0.771 | |||

| − | 109 (49) | 85 (50) | 24 (46) | |

| + | 114 (51) | 86 (50) | 28 (54) | |

| FLD, n (%) | 1 | |||

| − | 81 (36) | 62 (36) | 19 (37) | |

| + | 142 (64) | 109 (64) | 33 (63) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.71 (23.60, 28.18) | 25.71 (23.59, 27.51) | 26.20 (24.00, 29.48) | 0.067 |

| ALT (U/L) | 29.90 (19.91, 45.72) | 29.90 (20.25, 44.40) | 29.65 (19.65, 52.57) | 0.665 |

| AST (U/L) | 26.30 (19.65, 34.55) | 26.20 (19.65, 31.60) | 26.75 (19.67, 41.65) | 0.501 |

| UA (μmol/L) | 373.80 (293.15, 450.90) | 373.80 (295.50, 447.15) | 371.25 (286.80, 466.60) | 0.703 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 6.53 (5.30, 8.73) | 6.45 (5.36, 8.32) | 7.37 (5.22, 10.27) | 0.476 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 7.45 (4.23, 12.20) | 7.21 (4.06, 12.2) | 9.44 (5.58, 12.21) | 0.181 |

| HLD (mmol/L) | 0.95 (0.81, 1.17) | 0.99 (0.85, 1.19) | 0.91 (0.70, 1.08) | 0.005 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 3.12±1.26 | 3.18±1.25 | 2.94±1.28 | 0.247 |

| GLU (mmol/L) | 7.40 (6.13, 9.75) | 6.86 (5.88, 8.36) | 10.55 (8.02, 14.73) | < 0.001 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 2.33 (2.25, 2.42) | 2.33 (2.26, 2.43) | 2.31 (2.14, 2.38) | 0.029 |

| AMY (U/L) | 117.40 (67.30, 285.75) | 117.40 (69.25, 277.35) | 117.85 (61.27, 339.47) | 0.781 |

| Severity, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| MAP | 153 (69) | 138 (81) | 15 (29) | |

| MSAP | 58 (26) | 30 (18) | 28 (54) | |

| SAP/CAP | 12 (5) | 3 (2) | 9 (17) | |

| RAP, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| − | 155 (70) | 138 (81) | 17 (33) | |

| + | 68 (30) | 33 (19) | 35 (67) | |

| Fibrates, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| − | 105 (47) | 69 (40) | 36 (69) | |

| + | 118 (53) | 102 (60) | 16 (31) | |

Note: −: no, +: yes, BMI: body mass index, WBC: white blood cells, NEU: neutrophils, CRP: C-reactive protein, FLD: fatty liver disease, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, UA: uric acid, TC: cholesterol, TG: triglyceride, HDL: high-density lipoprotein, LDL: low-density lipoprotein, GLU: blood glucose value at admission, Ca: calcium, AMY: blood amylase, MAP: moderately acute pancreatitis, MSAP: moderately severe acute pancreatitis, SAP: severe acute pancreatitis, CAP: critical acute pancreatitis, RAP: recurrent acute pancreatitis.

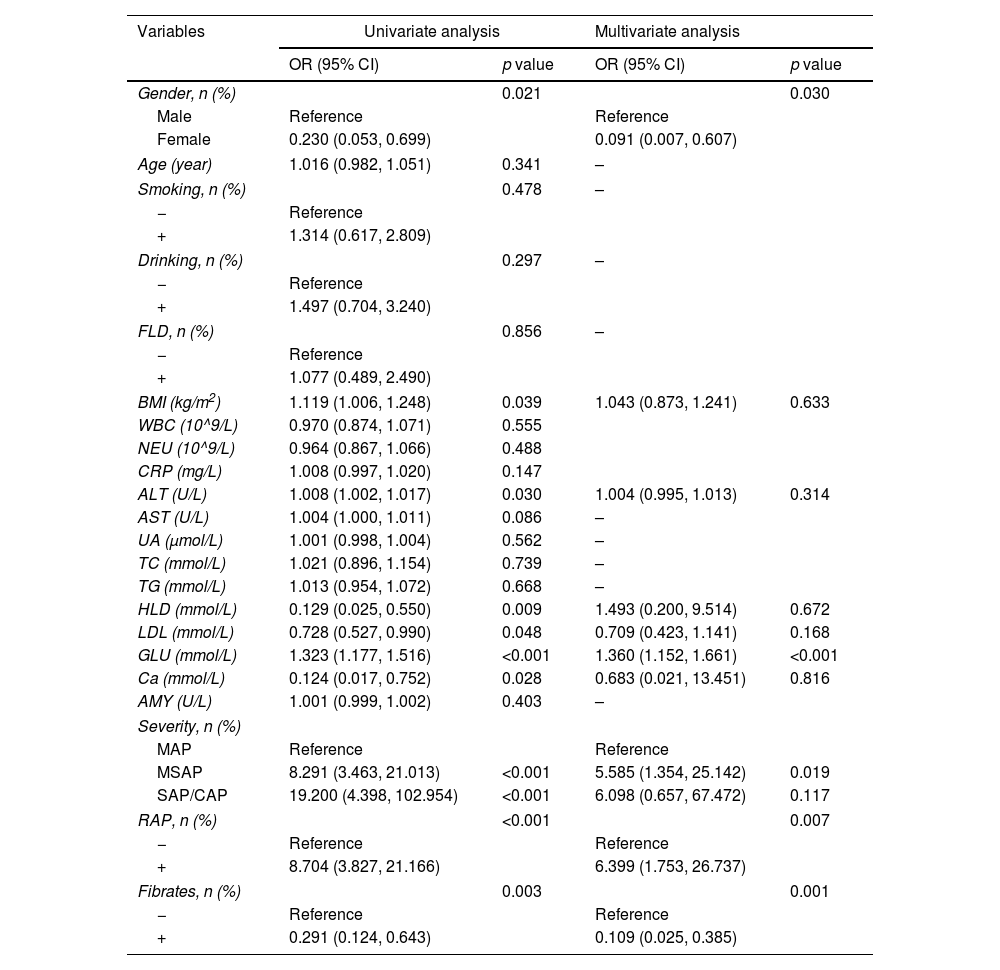

The study comprised 223 participants, distributed into training (n=156) and validation (n=67) groups at a ratio of 7:3. Baseline characteristics demonstrated no significant disparities between the two cohorts. In the training group, univariate logistic regression analysis unveiled significant associations between gender, BMI, ALT, HDL, LDL, GLU, Ca, severity of pancreatitis, RAP, and fibrates use with the incidence of PPDM-A (p<0.05). Conversely, variables such as age, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, FLD, WBC, NEU, CRP, AST, UA, TC, TG, LDL, and AMY displayed no statistical significance (p>0.05) (Table 2).

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression outcome for predicting PPDM-A.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.021 | 0.030 | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.230 (0.053, 0.699) | 0.091 (0.007, 0.607) | ||

| Age (year) | 1.016 (0.982, 1.051) | 0.341 | – | |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.478 | – | ||

| − | Reference | |||

| + | 1.314 (0.617, 2.809) | |||

| Drinking, n (%) | 0.297 | – | ||

| − | Reference | |||

| + | 1.497 (0.704, 3.240) | |||

| FLD, n (%) | 0.856 | – | ||

| − | Reference | |||

| + | 1.077 (0.489, 2.490) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.119 (1.006, 1.248) | 0.039 | 1.043 (0.873, 1.241) | 0.633 |

| WBC (10^9/L) | 0.970 (0.874, 1.071) | 0.555 | ||

| NEU (10^9/L) | 0.964 (0.867, 1.066) | 0.488 | ||

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.008 (0.997, 1.020) | 0.147 | ||

| ALT (U/L) | 1.008 (1.002, 1.017) | 0.030 | 1.004 (0.995, 1.013) | 0.314 |

| AST (U/L) | 1.004 (1.000, 1.011) | 0.086 | – | |

| UA (μmol/L) | 1.001 (0.998, 1.004) | 0.562 | – | |

| TC (mmol/L) | 1.021 (0.896, 1.154) | 0.739 | – | |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.013 (0.954, 1.072) | 0.668 | – | |

| HLD (mmol/L) | 0.129 (0.025, 0.550) | 0.009 | 1.493 (0.200, 9.514) | 0.672 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 0.728 (0.527, 0.990) | 0.048 | 0.709 (0.423, 1.141) | 0.168 |

| GLU (mmol/L) | 1.323 (1.177, 1.516) | <0.001 | 1.360 (1.152, 1.661) | <0.001 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 0.124 (0.017, 0.752) | 0.028 | 0.683 (0.021, 13.451) | 0.816 |

| AMY (U/L) | 1.001 (0.999, 1.002) | 0.403 | – | |

| Severity, n (%) | ||||

| MAP | Reference | Reference | ||

| MSAP | 8.291 (3.463, 21.013) | <0.001 | 5.585 (1.354, 25.142) | 0.019 |

| SAP/CAP | 19.200 (4.398, 102.954) | <0.001 | 6.098 (0.657, 67.472) | 0.117 |

| RAP, n (%) | <0.001 | 0.007 | ||

| − | Reference | Reference | ||

| + | 8.704 (3.827, 21.166) | 6.399 (1.753, 26.737) | ||

| Fibrates, n (%) | 0.003 | 0.001 | ||

| − | Reference | Reference | ||

| + | 0.291 (0.124, 0.643) | 0.109 (0.025, 0.385) | ||

Note: −: no, +: yes, FLD: fatty liver disease, BMI: body mass index, WBC: white blood cells, NEU: neutrophils, CRP: C-reactive protein, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, UA: uric acid, TC: cholesterol, TG: triglyceride, HDL: high-density lipoprotein, LDL: low-density lipoprotein, GLU: blood glucose value at admission, Ca: calcium, AMY: blood amylase, MAP: moderately acute pancreatitis, MSAP: moderately severe acute pancreatitis, SAP: severe acute pancreatitis, CAP: critical acute pancreatitis, RAP: recurrent acute pancreatitis.

Subsequent multivariate logistic regression analysis identified independent factors contributing to PPDM-A, including female (OR=0.091, 95% CI: 0.007–0.607, p=0.030), GLU (OR=1.360, 95% CI: 1.152–1.661, p<0.001), severity of acute pancreatitis [moderately severe (OR=5.585, 95% CI: 1.354–25.142, p=0.019)], RAP (OR=6.399, 95% CI: 1.753–26.737, p=0.007), and utilization of fibrates (OR=0.109, 95% CI: 0.025–0.385, p=0.001) (Table 2).

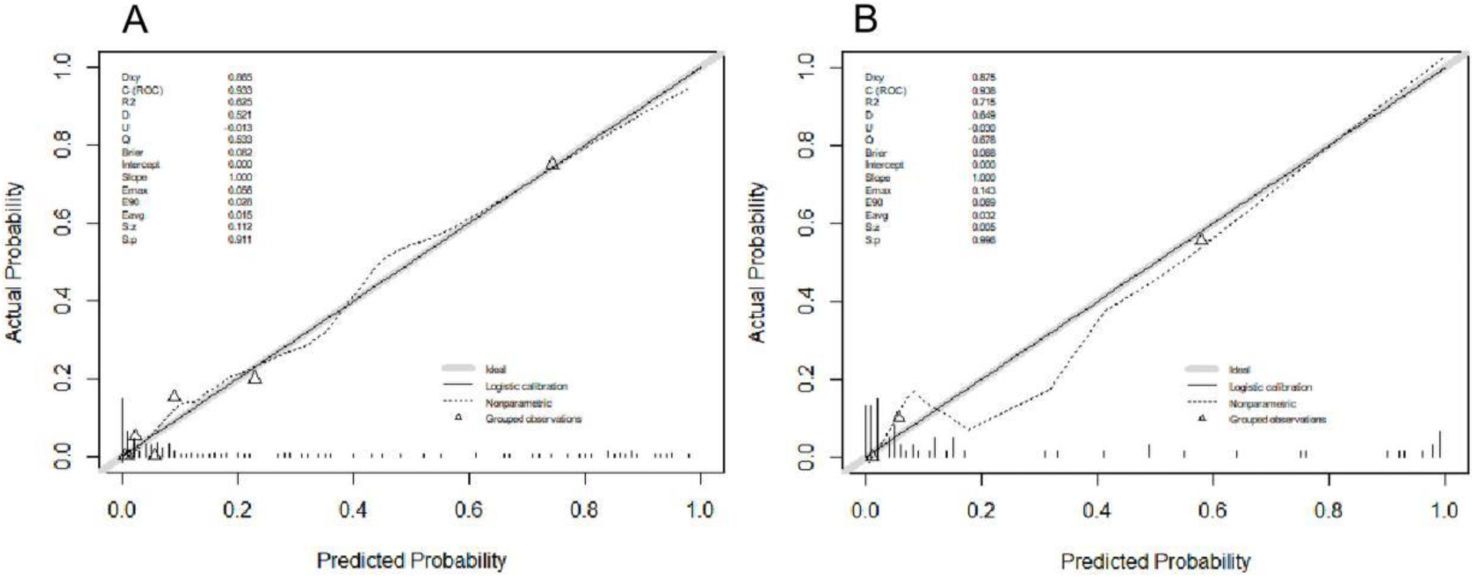

Furthermore, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve incorporating these five independent risk factors exhibited an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.936 in the training cohort. With a cut-off value of 0.319, sensitivity and specificity were determined as 0.901 and 0.829, respectively. Internal validation using 67 patients yielded an AUC of 0.938, with sensitivity and specificity of 0.980 and 0.824, respectively, at a cut-off value of 0.494 (Fig. 2). Additionally, calibration curves for both the training and validation cohorts closely approximated the ideal diagonal line (Fig. 3).

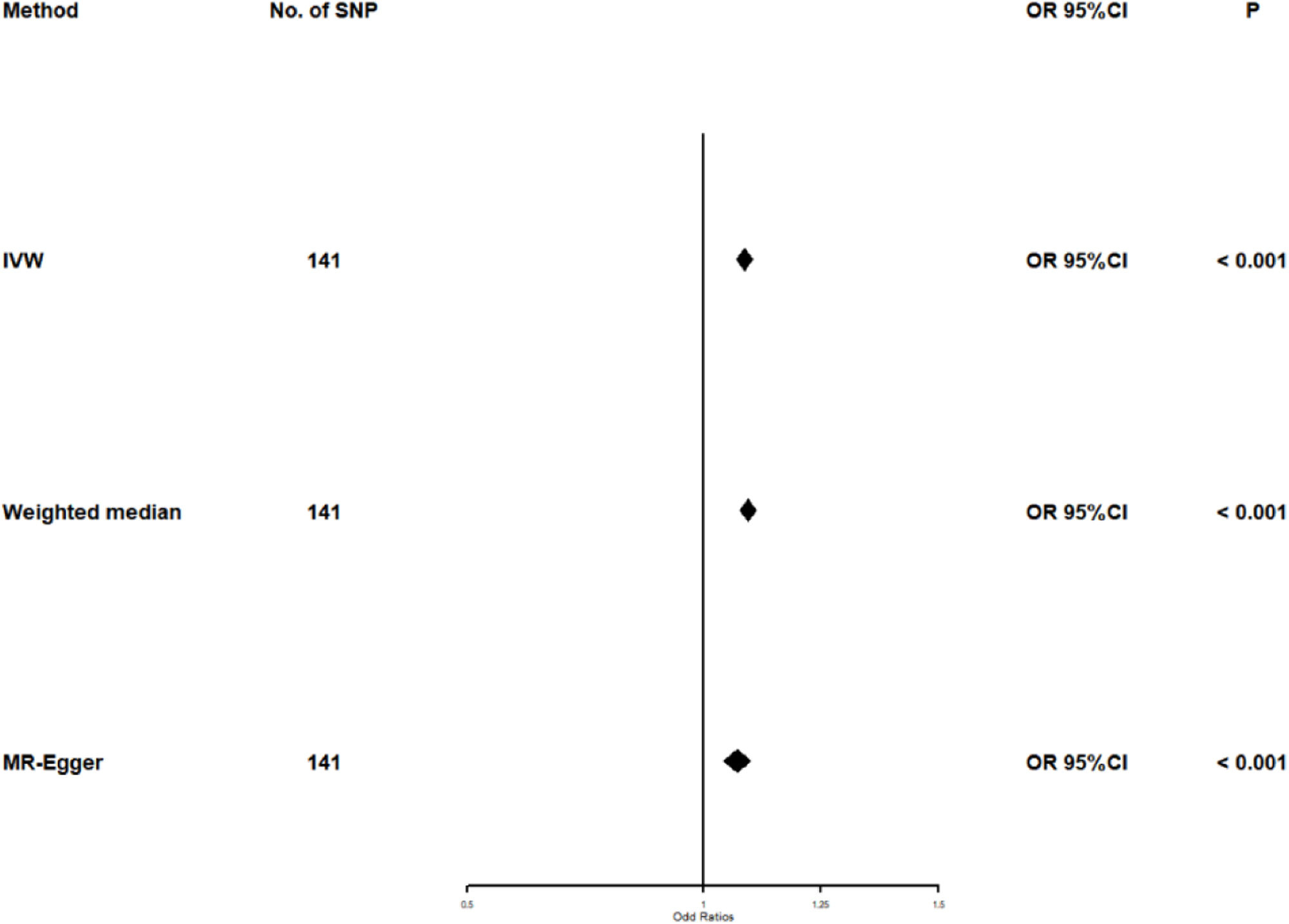

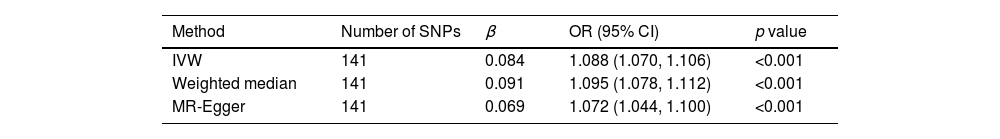

Selected SNPs for TGAfter excluding SNPs that did not meet the criteria for genome-wide significance (p<5×10^−6) and those with linkage imbalance (r2<0.001), a total of 141 TG-associated SNPs were selected. Additionally, these SNPs have an F-statistic greater than 10.

Univariate Mendelian randomization and Mediation analysisThe study utilizing Mendelian randomization (MR) found a causal relationship between triglyceride levels and the risk of diabetes, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.088 (95% CI: 1.070–1.106, p<0.001). The F statistics for this analysis were 98 (see Table 3 and Fig. 4). Additionally, the MR-Egger intercept analysis did not provide conclusive evidence of horizontal pleiotropy (p=0.138). Scatter plots illustrating the association between triglyceride levels and diabetes risk are presented in Fig. 5.

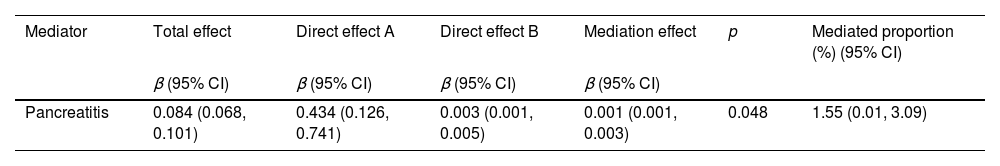

Next, a mediation analysis using a two-step MR approach was conducted to examine whether pancreatitis plays a causal role in the pathway between triglycerides and diabetes. In the first step, a causal link was established between triglyceride levels and pancreatitis (IVW β=0.434; 95% CI: 0.126–0.741, p=0.006) (see Table 4). The second step revealed an estimate of the effect of pancreatitis on diabetes (IVW β=0.003; 95% CI: 0.001–0.005, p=0.007) (see Table 4).

The study estimated the indirect effect of triglycerides on diabetes through pancreatitis, finding that the intermediary effect of pancreatitis was 0.001 (95% CI: 0.001–0.003, p=0.048). It concluded that 1.55% (95% CI: 0.01–3.09%) of the effect of triglycerides on diabetes risk was mediated through pancreatitis (see Table 4).

DiscussionPost-acute pancreatitis diabetes mellitus (PPDM-A) is a form of diabetes resulting from dysfunction of the exocrine pancreas. Although the precise etiology of this condition remains incompletely understood, it is associated with a heightened risk of pancreatic cancer and mortality compared to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Our Mendelian randomization analysis unveiled a compelling causal connection between triglyceride levels and diabetes. Increased triglyceride levels in circulation can detrimentally affect insulin sensitivity, potentially attributed to genetic variations in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ),15 or via the IkB kinase (IKK)/nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway, linking the immune system to fat-induced insulin resistance.16 Impairment in insulin secretion or insulin resistance diminishes the activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), an enzyme crucial for triglyceride breakdown, resulting in elevated blood triglyceride levels, as LPL function is insulin-dependent.11 Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1) plays a pivotal role in the regulation of LPL, facilitating its transportation from parenchymal cells to the luminal surface of capillary endothelial cells, essential for efficient lipolysis.11 Mutations in GPIHBP1 may predispose individuals to severe hypertriglyceridemia and pancreatitis,11 while the presence of GPIGBP1 autoantibodies has been associated with severe hypertriglyceridemia and recurrent acute pancreatitis.17

Hyperlipidemia is closely linked to diabetes. In our retrospective study, we discovered that lowering lipid levels can decrease the incidence of PPDM-A. In our two-step Mendelian randomization analysis, we identified a causal relationship between triglyceride levels and diabetes risk, with pancreatitis partially mediating this effect. Lowering triglyceride levels can reduce the likelihood of pancreatitis and, consequently, the overall risk of diabetes. This supports the findings of our retrospective study. Although our retrospective study was unable to obtain triglyceride measurements at the 3-month post-onset interval, extensive clinical evidence substantiates the triglyceride-lowering efficacy of fibrates.18,19 Notably, fenofibrate demonstrates 20–50% reductions in triglyceride levels during hypertriglyceridemia management, with pronounced efficacy observed particularly in patients manifesting metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes.20 These findings collectively highlight the promising therapeutic potential of fenofibrate for PPDM-A prophylaxis.

Fibrates, derived from fibric acid, reduce triglyceride (TG) levels and suppress hepatic apoC-III production.8 Furthermore, they augment LPL-mediated lipolysis through activation of transcription factors associated with Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPAR-α).8 Despite limited research on fibrates and PPDM-A, existing studies indicate potential benefits, such as improving insulin sensitivity by reducing plasma triglycerides and ameliorating liver and muscle steatosis.21,22 Additionally, fibrates exhibit therapeutic promise in diabetic retinopathy (DR) management, with documented effects on retinal vascular permeability reduction and preservation of white matter. Moreover, fibrates down-regulate vascular endothelial growth factor and mitigate endothelial and pericyte loss, offering therapeutic potential in managing DR-associated complications.23 Notably, fibrates have demonstrated efficacy in slowing the progression of diabetic eye diseases, including diabetic macular edema and proliferative diabetic retinopathy, with reduced reliance on laser treatment.23–26

Our study also identified several independent risk factors associated with PPDM-A, including gender, hyperglycemia at admission, recurrence of pancreatitis, the severity of pancreatitis, and fibrate use. These risk factors have been reported in multiple studies. As highlighted in a review, patients under 40 years of age, male, and with either a lean or overweight physique, who develop pancreatitis and subsequent exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, are at the highest risk for developing PPDM-A.27 Additionally, admission hyperglycemia has been identified as an independent risk factor in a retrospective study of 820 patients using machine learning algorithms.28 Patients with recurrent pancreatitis often experience more difficult glycemic control and are considered at increased risk for further recurrence. Recurrent episodes of pancreatitis can impair the endocrine function of the pancreas and also lead to changes in pancreatic volume. After two or more episodes of AP, the total volume of the pancreas significantly decreases. It is known that the highest proportion of pancreatic islets is located in the tail of the pancreas, rather than the head or body. Following two or more episodes of AP, there is a significant reduction in the pancreatic tail, which correlates with a reduction in β-cell mass.29 A recent prospective cohort study involving 187 youth patients (aged under 21 years) found that CRP levels and the severity of pancreatitis serve as independent risk factors for PPDM-A.30 However, in our study, CRP did not show a statistically significant association with the risk of PPDM-A. This may be attributed to the fact that CRP levels were measured at admission, typically within hours of pancreatitis onset, while CRP peaks usually occur 24–48h after the initial onset. This temporal discrepancy may account for the observed result. Future prospective, multicenter studies are warranted to further explore this association.

Early identification and prompt intervention for PPDM-A are crucially important. Begin the treatment plan with a focus on behavioral and lifestyle interventions, which should encompass alcohol withdrawal support, a well-balanced diet, regular exercise, and attention to neurological, cognitive, and mental health concerns, as well as effective pain control strategies.27 It is also crucial to incorporate medication management, including the use of dietary fiber, pancreatic enzyme supplementation, insulin therapy, oral hypoglycemic agents, and appropriate osteoporosis treatment.27 In our research, we discovered that the act of lowering lipid levels has shown to have a positive impact on the prevention of PPDM-A. This discovery presents a promising new avenue for both preventing and treating PPDM-A. However, to solidify and validate our findings, further randomized controlled studies will be required.

Several limitations of this study warrant acknowledgment. Firstly, its retrospective single-center design necessitates further investigation in larger, multicenter settings to validate the association between lipid-lowering therapy and PPDM-A. Secondly, the study predominantly focused on the association between fibrates and PPDM-A, necessitating additional research to explore the relationship between other lipid-lowering agents and PPDM-A. Furthermore, the impact of lipid-lowering medication duration on PPDM-A was inadequately explored due to the study's retrospective nature. Future studies should address these limitations to provide comprehensive insights into the association between lipid-lowering medications and PPDM-A.

ConclusionIn summary, our research highlights the potential benefits of using fibrate treatment to reduce the risk of PPDM-A in comparison to untreated patients. Furthermore, there is a direct correlation between triglyceride levels and the risk of diabetes, which is partly influenced by pancreatitis. These results underscore the significance of using fibrates to assess the prevention of PPDM-A.

Authors’ contributionsJiali Xu and Nana Deng contributed equally to this study. Jiali Xu, Mingming Deng, and Gang Luo contributed to the study design. Jiali Xu, Nana Deng, and Zhouyue Zhang contributed to data acquisition. Jiali Xu, Nana Deng, Zhouyue Zhang, Mingming Deng, and Gang Luo contributed to statistical analysis, data interpretation, writing the manuscript, literature search and funds collection.

Ethical statementThis study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University with batch number KY2023253.

FundingThis work was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (grant number: 2022YFS0626) and the Luzhou Municipal People's Government-Southwest Medical University Science and Technology Strategic Cooperation Project (grant number: 2020LZXNYDZ02).

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.