While several studies have examined the correlation between vitamin D concentrations and post-surgical nosocomial infections, this relationship has yet to be characterized in hepatobiliary surgery patients. We investigated the relationship between serum vitamin D concentration and the incidence of surgical site infection (SSI) in patients in our hepatobiliary surgery unit.

MethodsParticipants in this observational study were 321 successive patients who underwent the following types of interventions in the hepatobiliary surgery unit of our center over a 1-year period: cholecystectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, total pancreatectomy, segmentectomy, hepatectomy, hepaticojejunostomy and exploratory laparotomy. Serum vitamin D levels were measured upon admission and patients were followed up for 1 month. Mean group values were compared using a Student's T-test or Chi-squared test. Statistical analyses were performed using the Student's T-test, the Chi-squared test, or logistic regression models.

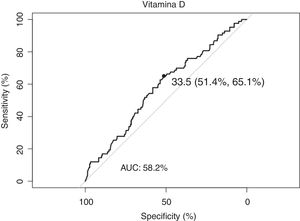

ResultsSerum concentrations >33.5 nmol/l reduced the risk of SSI by 50%. Out of the 321 patients analyzed, 25.8% developed SSI, mainly due to organ-cavity infections (incidence, 24.3%). Serum concentrations of over 33.5 nmol/l reduced the risk of SSI by 50%.

ConclusionsHigh serum levels of vitamin D are a protective factor against SSI (OR, 0.99). Our results suggest a direct relationship between serum vitamin D concentrations and SSI, underscoring the need for prospective studies to assess the potential benefits of vitamin D in SSI prevention.

La relación entre las infecciones nosocomiales en pacientes quirúrgicos y la vitamina D ha sido estudiada por algunos autores. Sin embargo, hasta la fecha no existe ningún estudio realizado sobre pacientes de cirugía hepatobiliar. El objetivo de nuestro trabajo es estudiar la infección del sitio quirúrgico (ISQ) en la unidad de cirugía hepatobiliar, y valorar su relación con la concentración sérica de vitamina D.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio analítico observacional de pacientes sucesivos intervenidos en la unidad de cirugía hepatobiliar de nuestro centro durante un año. Se incluyeron las intervenciones relativas a enfermedad biliar, pancreática y hepática. Se determinaron los niveles de vitamina D al ingreso, así como las ISQ de tipo superficial, profunda y Organ/space diagnosticadas durante el estudio. El seguimiento del paciente se realizó durante al menos un mes tras la cirugía, dependiendo de la enfermedad. La estadística se realizó mediante el programa estadístico R v.3.1.3.

ResultadosLa muestra quedó constituida por 321 pacientes, de los cuales el 25,8% presentó ISQ a expensas fundamentalmente de las infecciones Organ/spaces que presentaron una incidencia del 24,3%. Concentraciones séricas superiores a 33,5 nmol/l demostraron reducir en un 50% el riesgo de ISQ.

ConclusionesLas concentraciones elevadas de vitamina D en sangre demostraron ser un factor protector frente a las ISQ (OR: 0,99). Nuestros resultados sugieren una relación directa entre la concentración sérica de vitamina D y la ISQ, justificando la realización de nuevos estudios prospectivos.

Hepatobiliary surgery is a highly complex type of surgery from both a technical and anesthetic standpoint. Morbidity rates after liver surgery range from 17% in benign disease to 27% in malignant disease, with mortality rates close to 5%.1

As for pancreatic resections, overall morbidity rates range between 50% and 60% (59% for pancreatic head resection, 35% for distal resection and 46.7% for total pancreatectomy), depending on the series. The most frequent complications are collections (15.4%) and intra-abdominal abscesses (13.7%). In these procedures, overall mortality is around 3%.2,3

In 2018, Takahashi et al. published a study analyzing the risk factors for surgical site infection (SSI)4 after liver and pancreatic surgery in 735 patients, obtaining a total SSI rate of 17.8%. The interventions with the highest incidence of SSI were hepatectomies with bile duct resection (39.1%), pancreaticoduodenectomies (28.8%) and distal pancreatectomies (29.8%).5 A higher prevalence of the organ/space type was registered, with rates ranging from 25.1% in major hepatectomies to 39.1% in the case of pancreaticoduodenectomies.6

As for cholecystectomy, SSI rates are around 7% in open surgery and barely 1% in elective laparoscopic surgery.5,7

Currently, initiatives like Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) seek to improve patients’ preoperative conditions and to improve recovery with the multidisciplinary application of a series of surgical and anesthetic measures.1

Vitamin D has been studied by certain authors for the prevention of nosocomial infections due to its influence on immune system function, since its receptors are expressed by macrophages, B and T lymphocytes, and neutrophils. It is also involved in the synthesis of antimicrobial peptides responsible for innate immunity.8–12

In the case of SSI in particular, publications like the Abdehgah AG et al. study have documented that preoperative vitamin D levels have a significant influence on SSI rates and are considered a protective factor.12

However, no study has addressed its influence on SSI in hepatobiliary surgery in particular. Therefore, the objective of our study is to study SSI in the hepatobiliary surgery unit of our hospital and assess its relationship with preoperative serum vitamin D concentrations.

MethodsA prospective, analytical, observational study was carried out with consecutive patients treated by the hepatobiliary surgery unit of a tertiary hospital during the period of one year. Approval was obtained for the study from the Aragón Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CEICA), and patients gave their informed consent.

Patients who were admitted to the unit for either urgent or scheduled procedures, with hospital stays longer than 48 h, were included in the study. The surgeries analyzed included: cholecystectomy, segmentectomy, minor hepatectomy (<3 segments), major hepatectomy (> 3 segments), distal pancreatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, total pancreatectomy, exploratory laparotomy, and hepaticojejunostomy.

Serum concentrations of vitamin D were determined in all patients both upon admission and afterwards. Superficial, deep and organ/space SSI diagnosed during the study were monitored, both during hospitalization and at the postoperative follow-up office visits one month after surgery and in some cases until June 2019 if the patients had more than one follow-up appointment.

The following data were collected for all patients included in the study: comorbidities, ASA13 and Charlson14 indices, diagnostic data, treatment, NNIS index,4,6 procedural data, results (Clavien-Dindo scale),15 readmissions, reoperations, ICU admission and stay, total hospital stay, mortality, infection and serum concentrations of vitamin D. The diagnosis of infection was made using CDC criteria.16

Vitamin D determinations were performed in the clinical biochemistry laboratory at our hospital with an automated immunoassay using Alinity i 25-OH-vitamin D (Abbot, USA).17,18

Following the guidelines of the Spanish Society for Bone Research and Mineral Metabolism (SEIOMM), vitamin D deficiency was defined as a serum concentration between 20−30 ng/ml (50−75 nmol/L), and deficiency was a level less than 20 ng/ml (< 50 nmol/L). Therefore, serum concentrations between 30 and 75 nmol/L were considered normal.19–21

Statistical analysisWith the data obtained, a database was prepared that was subsequently analyzed using R statistical software, version 3.1.3.

After verifying that they followed a normal distribution with the Shapiro-Wilk test, the quantitative variables were expressed with means and standard deviation. The qualitative variables were expressed through the distribution of frequencies in their categories.

Comparisons between means were made using Student’s t test (continuous variables) or the chi-square test with a correction for continuity (categorical variables). Odds ratios (OR) were calculated from logistic regression models, with the dependent variable (y) being the occurrence/absence of nosocomial infection, and the independent variable(s) were those that were considered of interest. The Wald test was used to calculate the significance of each coefficient of the model. P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

When the group variable had 3 categories, comparisons between means were made by analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. The bivariate comparisons (post-hoc) were carried out with the Tukey method for parametric variables or the Benjamini-Hochberg method if the explanatory variable did not have a normal distribution.

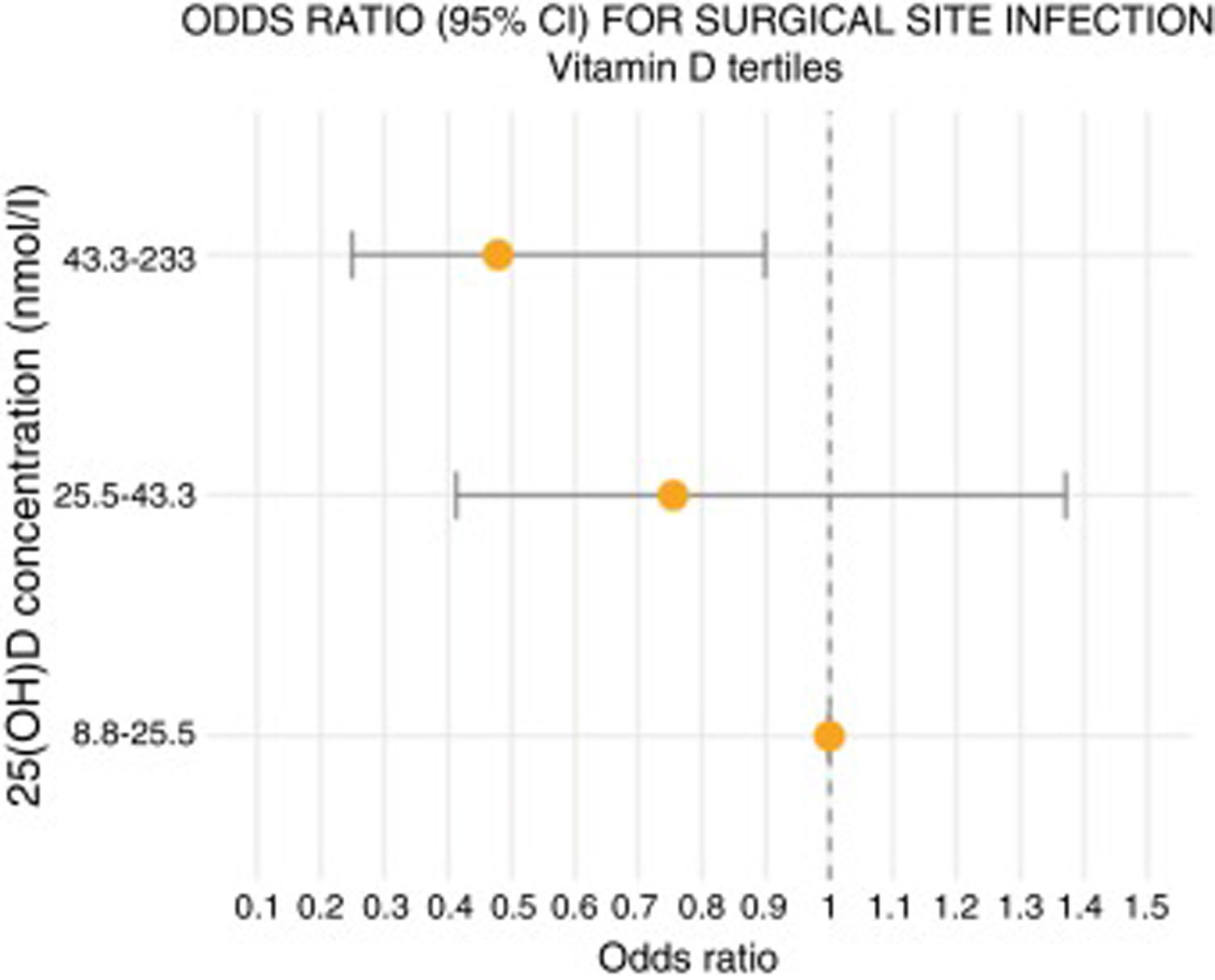

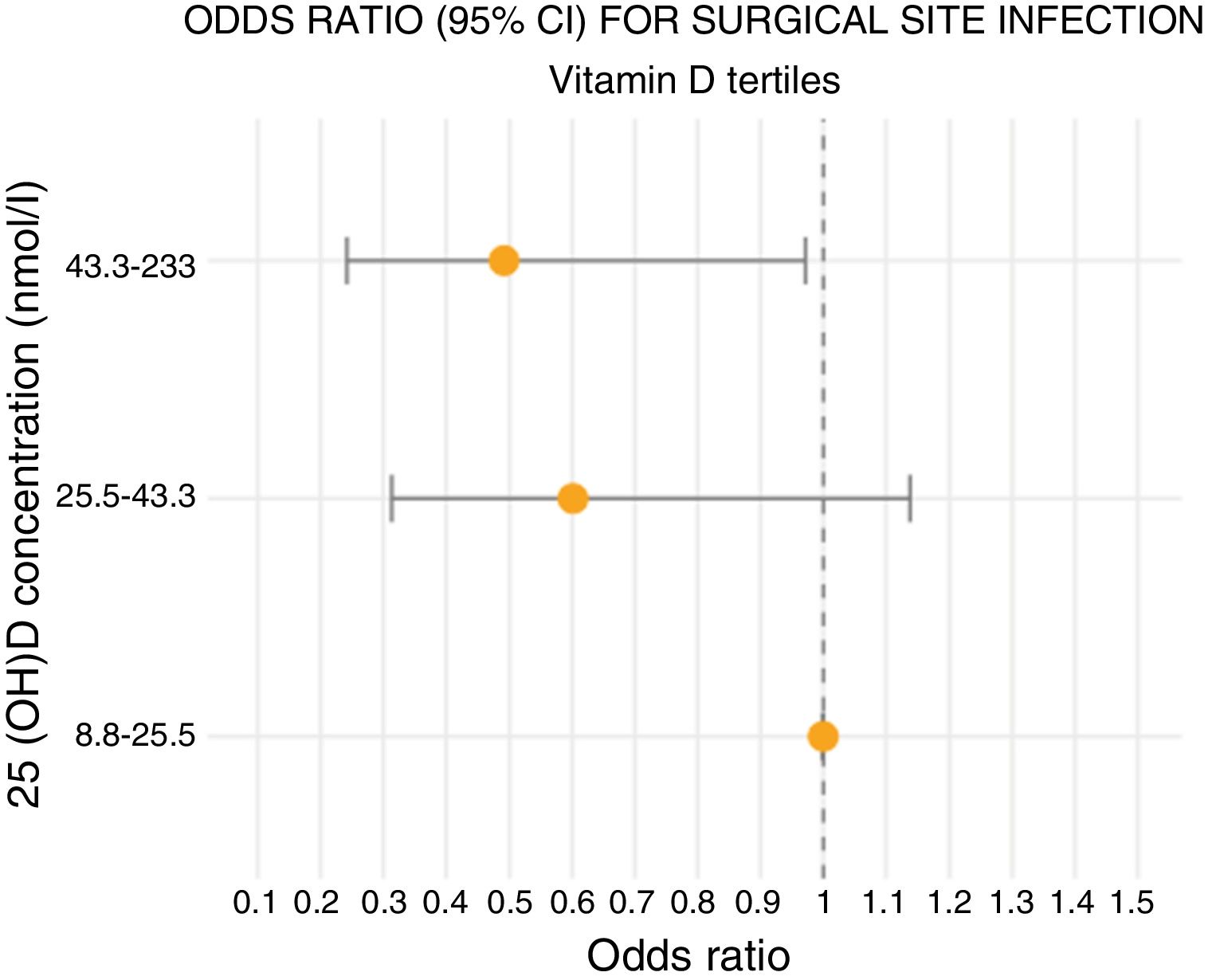

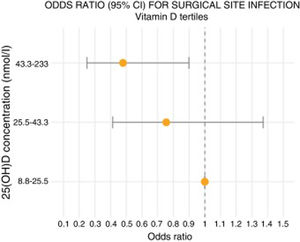

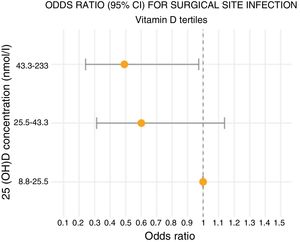

For the multivariate analysis of the sample, we decided to divide it into tertiles in order to obtain more balanced groups since its size did not allow for conclusions to be drawn with the divisions of the SEIOMM.

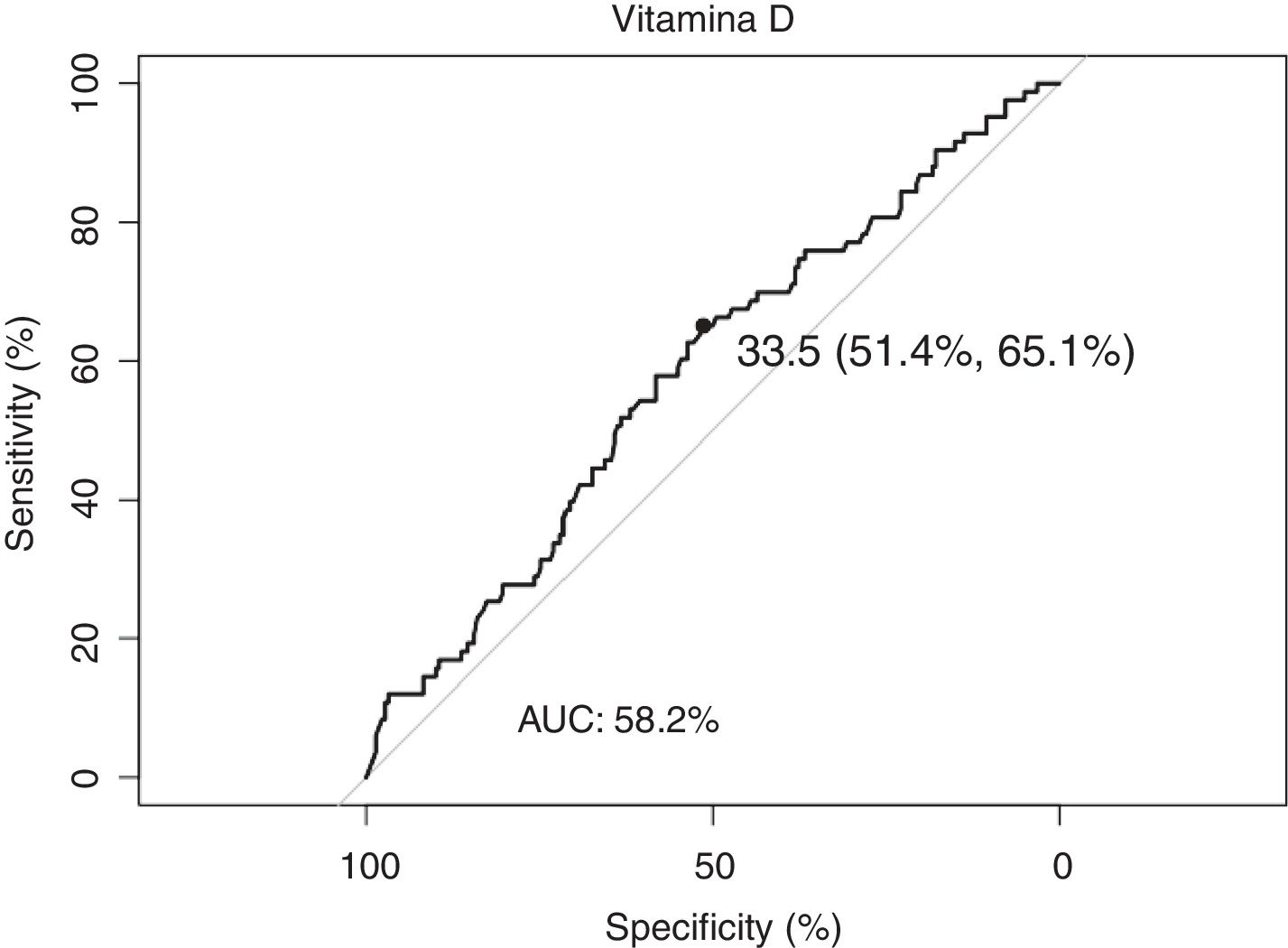

ROC curves were used to determine the sensitivity and specificity of plasma vitamin D concentrations as a predictor of SSI. We chose the cut-off point for vitamin D concentration that maximized specificity and sensitivity.

ResultsThe sample consisted of 321 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the study, from whom 301 vitamin D samples were obtained that were suitable for analysis. Twenty samples did not meet the conditions required by the analyzer (4 patients from the liver group, 15 from the gallbladder group and 1 from the pancreas group; none of them infected).

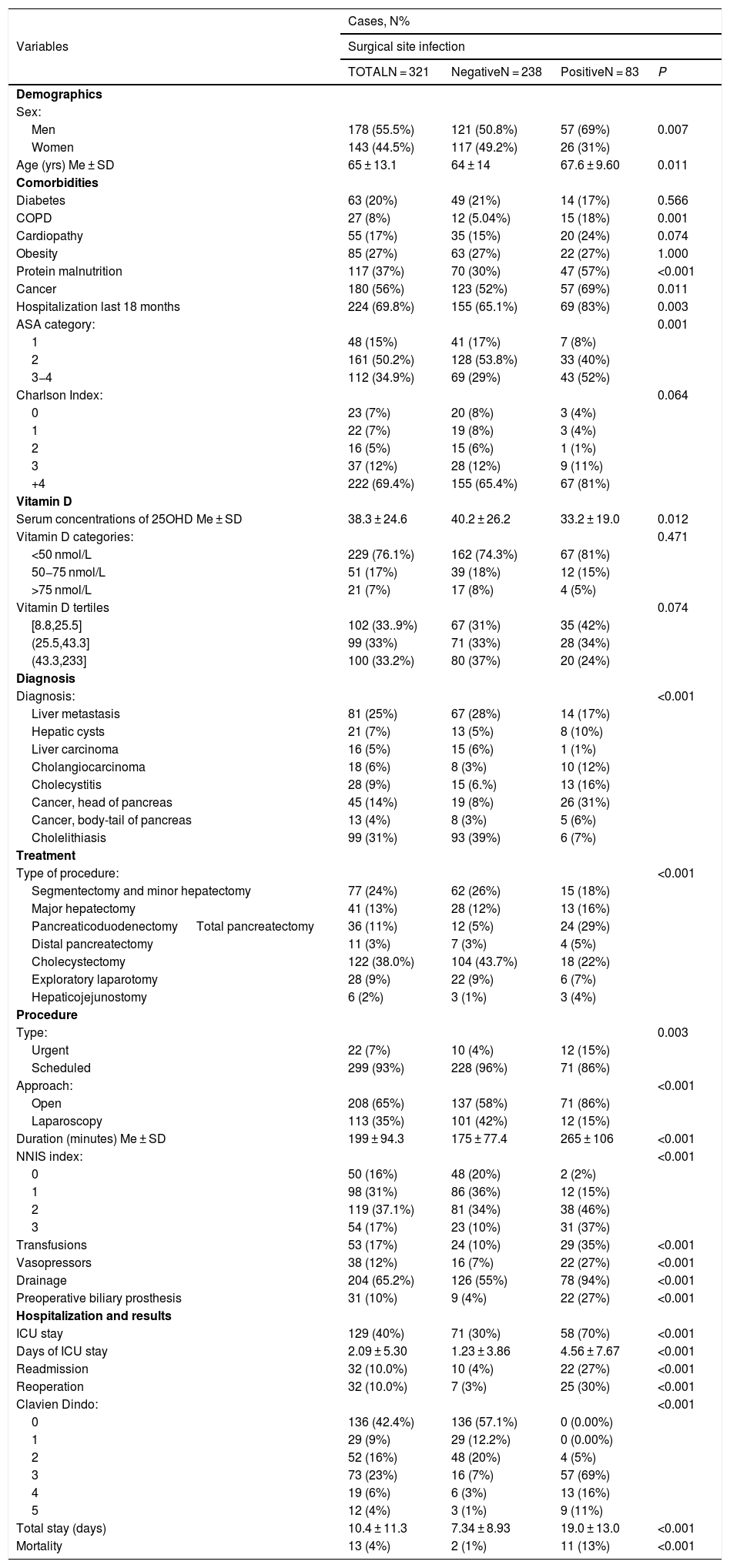

Out of the 321 patients, 178 (55.5%) were men and 143 (44.5%) were women, with a mean age of 65 ± 13 years. Their comorbidities, ASA and Charlson scores are shown in Table 1.

Patient characteristics grouped by the presence of surgical site infection. The percentages that are shown in each category have been calculated in relation to infection.

| Cases, N% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Surgical site infection | |||

| TOTALN = 321 | NegativeN = 238 | PositiveN = 83 | P | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Sex: | ||||

| Men | 178 (55.5%) | 121 (50.8%) | 57 (69%) | 0.007 |

| Women | 143 (44.5%) | 117 (49.2%) | 26 (31%) | |

| Age (yrs) Me ± SD | 65 ± 13.1 | 64 ± 14 | 67.6 ± 9.60 | 0.011 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 63 (20%) | 49 (21%) | 14 (17%) | 0.566 |

| COPD | 27 (8%) | 12 (5.04%) | 15 (18%) | 0.001 |

| Cardiopathy | 55 (17%) | 35 (15%) | 20 (24%) | 0.074 |

| Obesity | 85 (27%) | 63 (27%) | 22 (27%) | 1.000 |

| Protein malnutrition | 117 (37%) | 70 (30%) | 47 (57%) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 180 (56%) | 123 (52%) | 57 (69%) | 0.011 |

| Hospitalization last 18 months | 224 (69.8%) | 155 (65.1%) | 69 (83%) | 0.003 |

| ASA category: | 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 48 (15%) | 41 (17%) | 7 (8%) | |

| 2 | 161 (50.2%) | 128 (53.8%) | 33 (40%) | |

| 3−4 | 112 (34.9%) | 69 (29%) | 43 (52%) | |

| Charlson Index: | 0.064 | |||

| 0 | 23 (7%) | 20 (8%) | 3 (4%) | |

| 1 | 22 (7%) | 19 (8%) | 3 (4%) | |

| 2 | 16 (5%) | 15 (6%) | 1 (1%) | |

| 3 | 37 (12%) | 28 (12%) | 9 (11%) | |

| +4 | 222 (69.4%) | 155 (65.4%) | 67 (81%) | |

| Vitamin D | ||||

| Serum concentrations of 25OHD Me ± SD | 38.3 ± 24.6 | 40.2 ± 26.2 | 33.2 ± 19.0 | 0.012 |

| Vitamin D categories: | 0.471 | |||

| <50 nmol/L | 229 (76.1%) | 162 (74.3%) | 67 (81%) | |

| 50−75 nmol/L | 51 (17%) | 39 (18%) | 12 (15%) | |

| >75 nmol/L | 21 (7%) | 17 (8%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Vitamin D tertiles | 0.074 | |||

| [8.8,25.5] | 102 (33..9%) | 67 (31%) | 35 (42%) | |

| (25.5,43.3] | 99 (33%) | 71 (33%) | 28 (34%) | |

| (43.3,233] | 100 (33.2%) | 80 (37%) | 20 (24%) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Diagnosis: | <0.001 | |||

| Liver metastasis | 81 (25%) | 67 (28%) | 14 (17%) | |

| Hepatic cysts | 21 (7%) | 13 (5%) | 8 (10%) | |

| Liver carcinoma | 16 (5%) | 15 (6%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 18 (6%) | 8 (3%) | 10 (12%) | |

| Cholecystitis | 28 (9%) | 15 (6.%) | 13 (16%) | |

| Cancer, head of pancreas | 45 (14%) | 19 (8%) | 26 (31%) | |

| Cancer, body-tail of pancreas | 13 (4%) | 8 (3%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Cholelithiasis | 99 (31%) | 93 (39%) | 6 (7%) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Type of procedure: | <0.001 | |||

| Segmentectomy and minor hepatectomy | 77 (24%) | 62 (26%) | 15 (18%) | |

| Major hepatectomy | 41 (13%) | 28 (12%) | 13 (16%) | |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy Total pancreatectomy | 36 (11%) | 12 (5%) | 24 (29%) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 11 (3%) | 7 (3%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Cholecystectomy | 122 (38.0%) | 104 (43.7%) | 18 (22%) | |

| Exploratory laparotomy | 28 (9%) | 22 (9%) | 6 (7%) | |

| Hepaticojejunostomy | 6 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Procedure | ||||

| Type: | 0.003 | |||

| Urgent | 22 (7%) | 10 (4%) | 12 (15%) | |

| Scheduled | 299 (93%) | 228 (96%) | 71 (86%) | |

| Approach: | <0.001 | |||

| Open | 208 (65%) | 137 (58%) | 71 (86%) | |

| Laparoscopy | 113 (35%) | 101 (42%) | 12 (15%) | |

| Duration (minutes) Me ± SD | 199 ± 94.3 | 175 ± 77.4 | 265 ± 106 | <0.001 |

| NNIS index: | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 50 (16%) | 48 (20%) | 2 (2%) | |

| 1 | 98 (31%) | 86 (36%) | 12 (15%) | |

| 2 | 119 (37.1%) | 81 (34%) | 38 (46%) | |

| 3 | 54 (17%) | 23 (10%) | 31 (37%) | |

| Transfusions | 53 (17%) | 24 (10%) | 29 (35%) | <0.001 |

| Vasopressors | 38 (12%) | 16 (7%) | 22 (27%) | <0.001 |

| Drainage | 204 (65.2%) | 126 (55%) | 78 (94%) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative biliary prosthesis | 31 (10%) | 9 (4%) | 22 (27%) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization and results | ||||

| ICU stay | 129 (40%) | 71 (30%) | 58 (70%) | <0.001 |

| Days of ICU stay | 2.09 ± 5.30 | 1.23 ± 3.86 | 4.56 ± 7.67 | <0.001 |

| Readmission | 32 (10.0%) | 10 (4%) | 22 (27%) | <0.001 |

| Reoperation | 32 (10.0%) | 7 (3%) | 25 (30%) | <0.001 |

| Clavien Dindo: | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 136 (42.4%) | 136 (57.1%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| 1 | 29 (9%) | 29 (12.2%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| 2 | 52 (16%) | 48 (20%) | 4 (5%) | |

| 3 | 73 (23%) | 16 (7%) | 57 (69%) | |

| 4 | 19 (6%) | 6 (3%) | 13 (16%) | |

| 5 | 12 (4%) | 3 (1%) | 9 (11%) | |

| Total stay (days) | 10.4 ± 11.3 | 7.34 ± 8.93 | 19.0 ± 13.0 | <0.001 |

| Mortality | 13 (4%) | 2 (1%) | 11 (13%) | <0.001 |

SSI: surgical site infection; Me: median; SD: Standard deviation; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NNIS: National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance; ICU: Intensive care unit.

Note 1: Exploratory laparotomies were done in patients who were candidates for the procedure, but who were not candidates for surgery at the time of the operation due to progression of the disease.

Note 2: Four patients were excluded with diagnosis of liver metastases, one patient with cancer of the head of the pancreas and 15 patients with cholelithiasis because their samples were not viable for chromatographic analysis of vitamin D, with no presentations of SSI.

The mean serum concentration of vitamin D, assessed from the 301 viable samples, was 38.3 ± 24.6 nmol/L. More than 76.6% of patients presented <50 nmol/L of vitamin D, which were levels compatible with vitamin D deficiency, and 33.9% were within the lowest tertile (Table 1).

The overall SSI rate was 25.8%, and the interventions with the highest number of registered infections were pancreaticoduodenectomy and total pancreatectomy (29%), cholecystectomy (22%), segmentectomy and minor hepatectomy (<3 segments) (18 %).

SSI were shown to be significantly more prevalent in males (P = .007), patients with protein malnutrition (P < .001), neoplasms (P = .011) and hospitalization in the previous 18 months (P = .003). They also proved to be more frequent in patients with ASA III-IV, who constituted 51.8% of the infected group (P = .001) and with Charlson scores greater than 4 points (80.7%), although this latter case was not significant (P = .064) (Table 1).

The patients with SSI also presented lower concentrations of vitamin D (P = .012), with a mean of 33.2 ± 19 nmol/L. This significance was lost when the sample was divided into tertiles; however, the first tertile was constituted by 42.2% of the patients with SSI (Table 1).

When we analyzed the hospital results, patients with SSI had longer stays in the ICU (4.5 ± 7.7 days vs 1.2 ± 3.8 days) and higher rates of readmission, reoperation and mortality (P < .001) (Table 1).

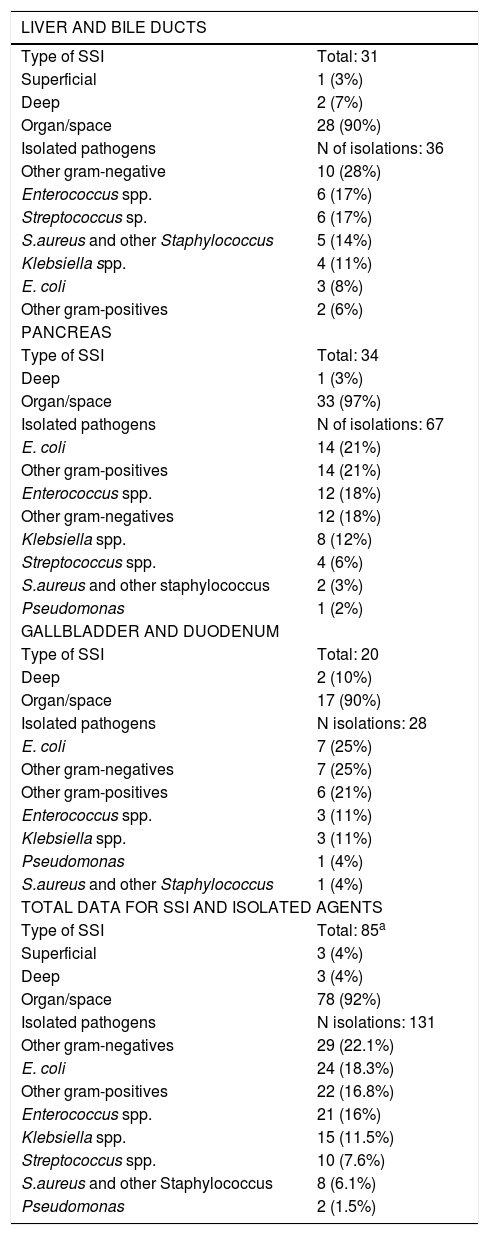

Regarding the type of SSI by diagnostic group, organ/space infection was the most frequent in all categories. The most frequently detected microorganisms were Escherichia coli and the ‘other gram-negative’ and ‘other gram-positive’ agents (Table 2).

Surgical site infections data and agents by diagnostic group and totals.

| LIVER AND BILE DUCTS | |

|---|---|

| Type of SSI | Total: 31 |

| Superficial | 1 (3%) |

| Deep | 2 (7%) |

| Organ/space | 28 (90%) |

| Isolated pathogens | N of isolations: 36 |

| Other gram-negative | 10 (28%) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 6 (17%) |

| Streptococcus sp. | 6 (17%) |

| S.aureus and other Staphylococcus | 5 (14%) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 4 (11%) |

| E. coli | 3 (8%) |

| Other gram-positives | 2 (6%) |

| PANCREAS | |

| Type of SSI | Total: 34 |

| Deep | 1 (3%) |

| Organ/space | 33 (97%) |

| Isolated pathogens | N of isolations: 67 |

| E. coli | 14 (21%) |

| Other gram-positives | 14 (21%) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 12 (18%) |

| Other gram-negatives | 12 (18%) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 8 (12%) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 4 (6%) |

| S.aureus and other staphylococcus | 2 (3%) |

| Pseudomonas | 1 (2%) |

| GALLBLADDER AND DUODENUM | |

| Type of SSI | Total: 20 |

| Deep | 2 (10%) |

| Organ/space | 17 (90%) |

| Isolated pathogens | N isolations: 28 |

| E. coli | 7 (25%) |

| Other gram-negatives | 7 (25%) |

| Other gram-positives | 6 (21%) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 3 (11%) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 3 (11%) |

| Pseudomonas | 1 (4%) |

| S.aureus and other Staphylococcus | 1 (4%) |

| TOTAL DATA FOR SSI AND ISOLATED AGENTS | |

| Type of SSI | Total: 85a |

| Superficial | 3 (4%) |

| Deep | 3 (4%) |

| Organ/space | 78 (92%) |

| Isolated pathogens | N isolations: 131 |

| Other gram-negatives | 29 (22.1%) |

| E. coli | 24 (18.3%) |

| Other gram-positives | 22 (16.8%) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 21 (16%) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 15 (11.5%) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 10 (7.6%) |

| S.aureus and other Staphylococcus | 8 (6.1%) |

| Pseudomonas | 2 (1.5%) |

SD: standard deviation; n: number of cases; Me: median; spp.: species.

The category “other gram-negatives” included: Enterobacter spp., Haemophillus spp., Citrobacter spp., etc; and “other gram-positives” included Corynebacterium spp., etc.

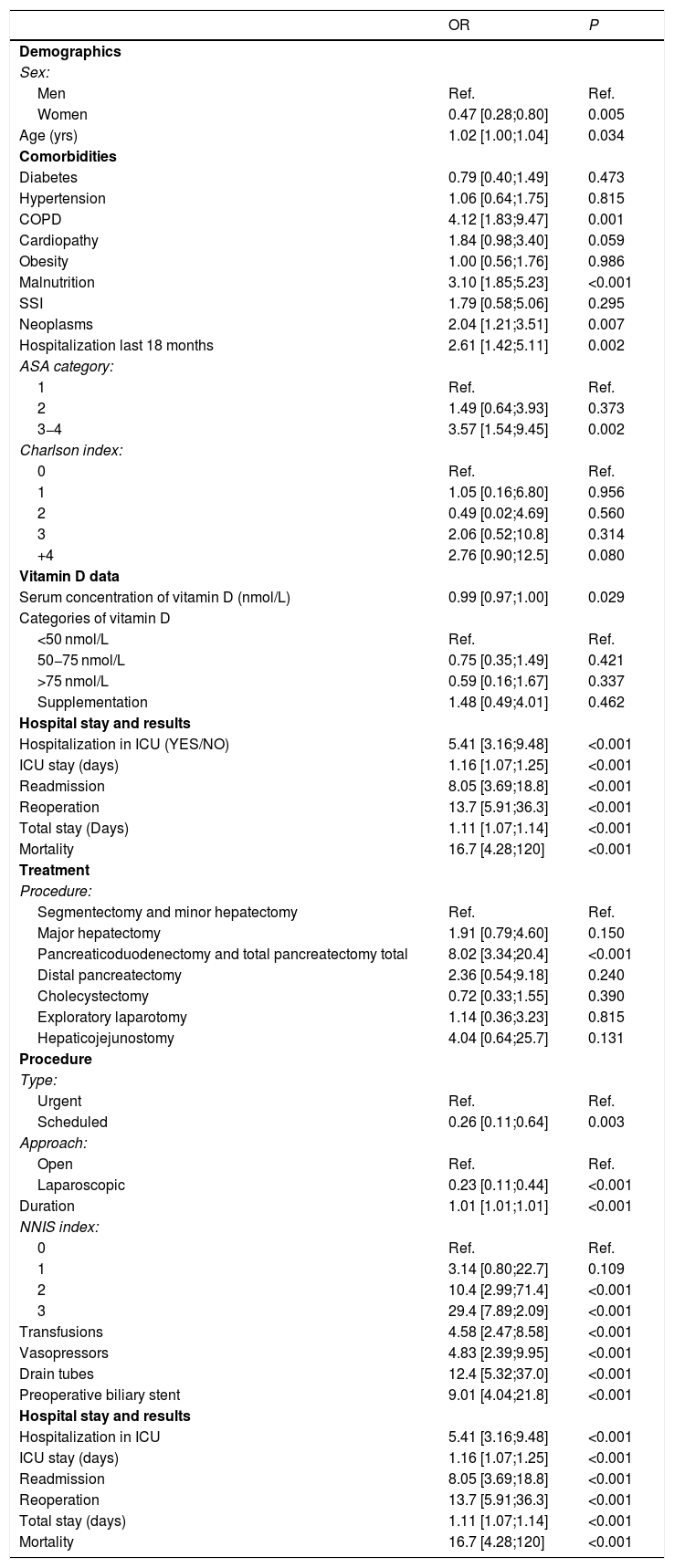

With regards to comorbidities in the univariate analysis, protein malnutrition (P < .001), neoplasms (P = .007) and hospitalization in the last 18 months (P = .002) were associated with an increased risk of up to 3 times higher (Table 3). In addition, patients who presented ASA III-IV experienced an SSI risk with nearly a four-fold increase (P = .002), as well as patients with high scores on the Charlson index (P < .001) and those that required transfusions and vasopressors with almost 5 times the risk.

Univariate analysis of the surgical site infection regarding the reference variable.

| OR | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Sex: | ||

| Men | Ref. | Ref. |

| Women | 0.47 [0.28;0.80] | 0.005 |

| Age (yrs) | 1.02 [1.00;1.04] | 0.034 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes | 0.79 [0.40;1.49] | 0.473 |

| Hypertension | 1.06 [0.64;1.75] | 0.815 |

| COPD | 4.12 [1.83;9.47] | 0.001 |

| Cardiopathy | 1.84 [0.98;3.40] | 0.059 |

| Obesity | 1.00 [0.56;1.76] | 0.986 |

| Malnutrition | 3.10 [1.85;5.23] | <0.001 |

| SSI | 1.79 [0.58;5.06] | 0.295 |

| Neoplasms | 2.04 [1.21;3.51] | 0.007 |

| Hospitalization last 18 months | 2.61 [1.42;5.11] | 0.002 |

| ASA category: | ||

| 1 | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2 | 1.49 [0.64;3.93] | 0.373 |

| 3−4 | 3.57 [1.54;9.45] | 0.002 |

| Charlson index: | ||

| 0 | Ref. | Ref. |

| 1 | 1.05 [0.16;6.80] | 0.956 |

| 2 | 0.49 [0.02;4.69] | 0.560 |

| 3 | 2.06 [0.52;10.8] | 0.314 |

| +4 | 2.76 [0.90;12.5] | 0.080 |

| Vitamin D data | ||

| Serum concentration of vitamin D (nmol/L) | 0.99 [0.97;1.00] | 0.029 |

| Categories of vitamin D | ||

| <50 nmol/L | Ref. | Ref. |

| 50−75 nmol/L | 0.75 [0.35;1.49] | 0.421 |

| >75 nmol/L | 0.59 [0.16;1.67] | 0.337 |

| Supplementation | 1.48 [0.49;4.01] | 0.462 |

| Hospital stay and results | ||

| Hospitalization in ICU (YES/NO) | 5.41 [3.16;9.48] | <0.001 |

| ICU stay (days) | 1.16 [1.07;1.25] | <0.001 |

| Readmission | 8.05 [3.69;18.8] | <0.001 |

| Reoperation | 13.7 [5.91;36.3] | <0.001 |

| Total stay (Days) | 1.11 [1.07;1.14] | <0.001 |

| Mortality | 16.7 [4.28;120] | <0.001 |

| Treatment | ||

| Procedure: | ||

| Segmentectomy and minor hepatectomy | Ref. | Ref. |

| Major hepatectomy | 1.91 [0.79;4.60] | 0.150 |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy and total pancreatectomy total | 8.02 [3.34;20.4] | <0.001 |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 2.36 [0.54;9.18] | 0.240 |

| Cholecystectomy | 0.72 [0.33;1.55] | 0.390 |

| Exploratory laparotomy | 1.14 [0.36;3.23] | 0.815 |

| Hepaticojejunostomy | 4.04 [0.64;25.7] | 0.131 |

| Procedure | ||

| Type: | ||

| Urgent | Ref. | Ref. |

| Scheduled | 0.26 [0.11;0.64] | 0.003 |

| Approach: | ||

| Open | Ref. | Ref. |

| Laparoscopic | 0.23 [0.11;0.44] | <0.001 |

| Duration | 1.01 [1.01;1.01] | <0.001 |

| NNIS index: | ||

| 0 | Ref. | Ref. |

| 1 | 3.14 [0.80;22.7] | 0.109 |

| 2 | 10.4 [2.99;71.4] | <0.001 |

| 3 | 29.4 [7.89;2.09] | <0.001 |

| Transfusions | 4.58 [2.47;8.58] | <0.001 |

| Vasopressors | 4.83 [2.39;9.95] | <0.001 |

| Drain tubes | 12.4 [5.32;37.0] | <0.001 |

| Preoperative biliary stent | 9.01 [4.04;21.8] | <0.001 |

| Hospital stay and results | ||

| Hospitalization in ICU | 5.41 [3.16;9.48] | <0.001 |

| ICU stay (days) | 1.16 [1.07;1.25] | <0.001 |

| Readmission | 8.05 [3.69;18.8] | <0.001 |

| Reoperation | 13.7 [5.91;36.3] | <0.001 |

| Total stay (days) | 1.11 [1.07;1.14] | <0.001 |

| Mortality | 16.7 [4.28;120] | <0.001 |

Ref.: reference category; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKF: chronic kidney failure; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; NNIS: National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance; ICU: intensive care unit.

The biliary stent category includes all patients who had a prosthesis prior to surgery.

Scheduled surgery and the laparoscopic approach showed a significant decrease in the risk of SSI (P = .003 and P < .001). Pancreaticoduodenectomies were the procedure type with the highest increased risk for SSI (P < .001).

High concentrations of vitamin D in the blood constituted a protective factor against SSI, presenting on the other hand a low level of significance (OR: 0.99; [0.97−0.99]).

Regarding the multivariate analysis of the sample by vitamin D tertiles, a significant increase in the OR was observed in patients located in the third tertile (vitamin D > 43.3 nmol/L) compared to the lowest tertile (vitamin D < 25 nmol/L), which resulted in a significant decrease in the risk of SSI when the serum concentration of vitamin D increased (Fig. 1).

These differences were also confirmed in the model adjusted for sex, age, Charlson and type of surgery (urgent/scheduled) (Fig. 2).

Finally, by analyzing the sensitivity and specificity of vitamin D as a predictor for SSI, we found that values greater than or equal to 33.5 nmol/L reduced the risk of developing SSI by 50% (Fig. 3).

DiscussionSSI ranks second among the most prevalent nosocomial infections, and it is the most frequent in surgical patients. Each SSI adds an average of 11 days to hospital stay and an average cost of €4,000.22–24

Our study registered 25.8% SSI, mainly organ/space infections (24.3%). This result is higher than the rates reported by Takahashi et al. and Moreno Elola-Olaso et al., who, in 2012, obtained post-hepatectomy infection rates of 4%-20% and an SSI incidence after liver resection of 2.1%-14.5%. However, the rates registered in our study were lower in terms of superficial and deep SSI, both of which were 1.2%.5,6

In contrast, major hepatectomies recorded results similar to those described above, with an SSI incidence of 31.7%, while pancreaticoduodenectomies had almost 67% SSI.5,6

These results, although high, should be analyzed in the context of our hospital, which is a referral center in our community for complex liver and pancreatic surgery.

As for cholecystectomies, the SSI rate was 1.5%, which is a lower result than other published reports if we take into account that the majority of infected patients underwent emergency and open surgery.5,7

There was also a lower incidence of SSI in the laparoscopic approach compared to open surgery, which is in line with what has been published to date, despite the fact that 65% of the interventions were performed with this approach.4

As for vitamin D, the mean concentration was 38.3 ± 24.6 nmol/L, compatible with deficiency. To date, the only study carried out in serum concentrations of vitamin D in non-cardiac surgery patients is the publication by Turan et al. in 2014, which registered an average of 23.5 ng/ml (also within the range of deficiency9). However, there have been studies in bariatric patients, such as the Quaraishi S.A. et al. study,25 which also obtained serum concentrations <30 ng/mL.

In 2012, Dima et al. published a bibliographic review on the potential effects of vitamin D in reducing nosocomial infections, which confirmed that vitamin D deficiency increased the predisposition towards Staphylococcus aureus infections and was associated with worse wound healing.21,26

According to serum concentrations of vitamin D, other studies have verified that there are differences in the results obtained in patients infected by certain microorganisms, such as Clostridium difficile, S. aureus, MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infected patients present hospital stays that are 4 times longer, at an increased cost of nearly five-fold.26,27

Regarding the microorganisms isolated in SSI, Múñez et al. conducted a study in 2011 in patients with digestive tract procedures, and they observed a predominance of gram-negative bacilli of digestive origin, together with gram-positive streptococci, enterococci and staphylococci. The most frequently isolated microorganisms were: Escherichia coli (28%), Enterococcus spp. (15%), Streptococcus spp. (8%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7%) and Staphylococcus aureus (5%).28

In our sample, we also verified a significant percentage of gram-negative infections of digestive origin (22%) and similar isolation rates for Enterococcus spp., Pseudomonas spp. and S. aureus, but fewer isolated E. coli (18%) (Table 2).

To date, no study of this type has been carried out to analyze the relationship between SSI and serum vitamin D concentrations in hepatobiliary surgery. Our study population was found to have levels similar to previous publications,9,25,26,29 confirming that protein malnutrition and prolonged surgical time were the main risk factors.6

We have verified the existence of significant differences in terms of SSI when comparing patients in the lower and upper tertiles, and there was a significant decrease in SSI risk of 50% with concentrations of 33.5 nmol/L or more.

As limitations of our study, it should be noted that we have tried to eliminate the possible confounding factors with statistical adjustment of the multivariate analysis and the study of multiple demographic variables. However, we are aware of other confounding factors that may have gone unnoticed. Furthermore, the sample does not have a sufficient size to draw conclusions by diagnostic group regarding SSI and vitamin D, which is a reason for to future studies with a larger sample size.

The results of our study suggest a correlation between serum vitamin D concentration and surgical SSI in hepatobiliary surgery, which justifies future prospective studies to assess the possible benefits of optimizing vitamin D before surgery and the influence of postoperative supplementation.

FundingNo external funding was received of any kind.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Laviano E, Sanchez M, González-Nicolás MT, Palacian MP, López J, et al. Infección del sitio quirúrgico en cirugía hepatobiliopancreática y su relación con la concentración sérica de vitamina D. Cir Esp. 2020;98:456–464.