Hilar cholangiocarcinoma is a tumor that is difficult to stage and radically treat, for which surgery is the only curative treatment. Furthermore, optimal preoperative management continues to be debated.1 Most patients present with obstructive jaundice, which represents an increased risk of postoperative complications.2 Preoperative biliary drainage is indicated in patients with jaundice prior to major liver resection.3

We present the case of a 68-year-old male diagnosed with Bismuth type II hilar cholangiocarcinoma (TNM: T2b, N1), who underwent right transparietohepatic external biliary drainage (8.5F) for preoperative optimization 2 weeks before surgery due to rapidly progressive jaundice (5.8mg/dL) and sepsis of possible biliary origin. The week prior to the procedure, he presented abdominal pain and fever, requiring repositioning and partial removal of the catheter, as well as conversion to internal-external drainage to prevent this complication from recurring. We later performed left hepatectomy, caudate resection, hilar lymphadenectomy and reconstruction using a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. The catheter was maintained after surgery as a percutaneous stent through the anastomosis and in order to perform follow-up cholangiography. Several previous studies have indicated that the use of transanastomotic stents could reduce the rate of anastomotic stenosis in unfavorable conditions.4

In the immediate postoperative period, the patient presented a biliary fistula, which was managed by opening the catheter, and infection of the surgical wound. Both complications evolved favorably with combined medical treatment.

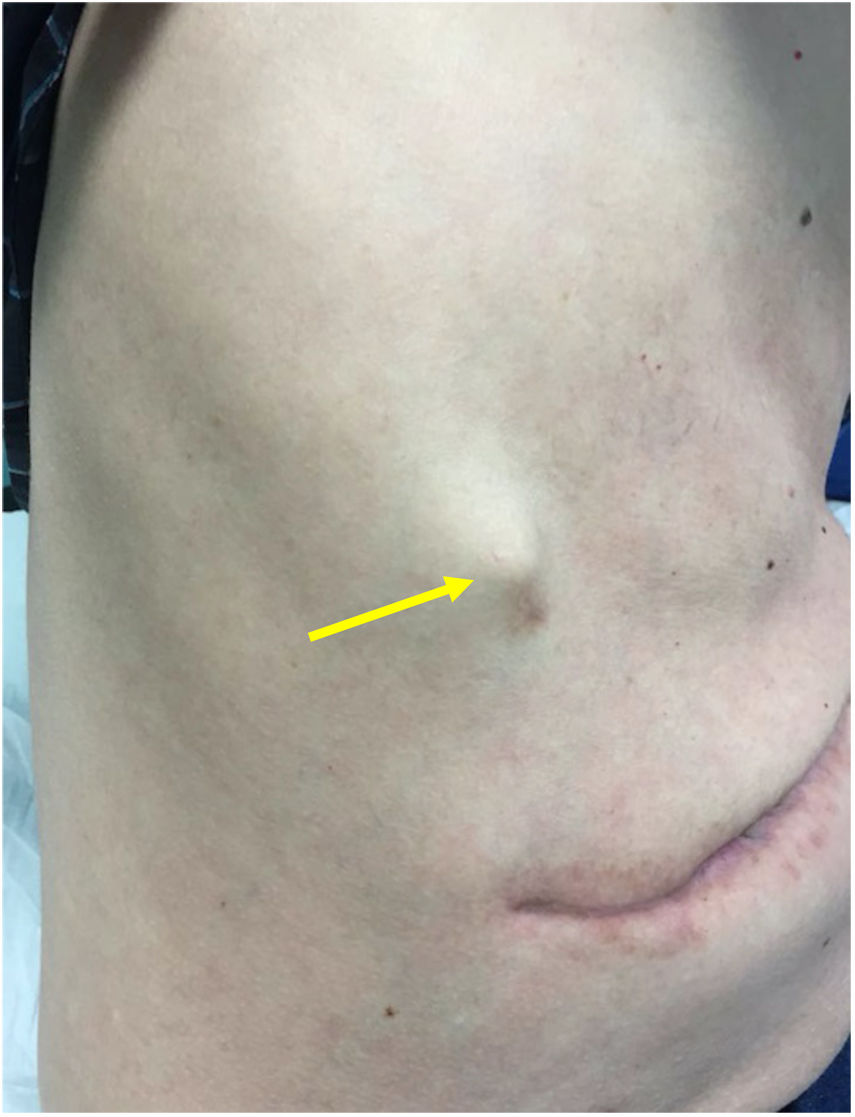

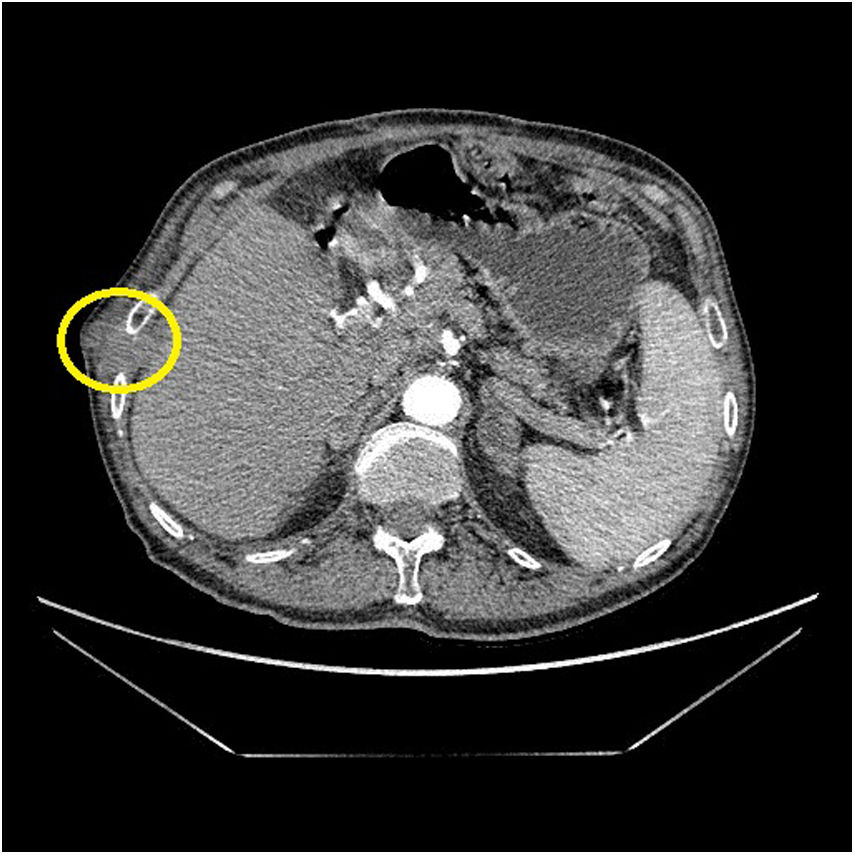

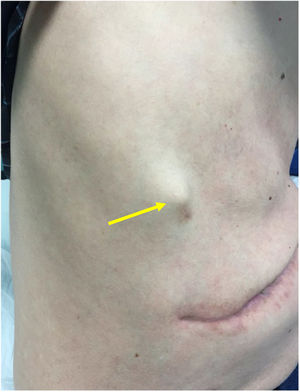

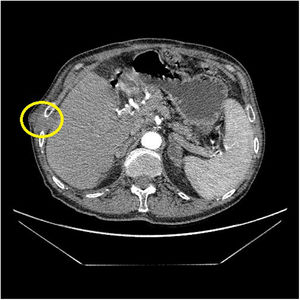

In the third postoperative month, the patient presented intense pain in the right shoulder and rib cage, with no functional limitation. On physical examination, we observed a 20mm nodule in size on the right rib cage that was very painful and appeared to be attached to the wall at the point of entry of the transparietal drain tube (Fig. 1). Computed tomography scan revealed a 30cm nodule in the subcutaneous cell tissue (Fig. 2) that, after core needle biopsy, was diagnosed as metastatic adenocarcinoma of pancreatobiliary origin (CK19 and TTF-1+, CA 19.9 and napsin−). Positron emission tomography showed uptake of the 30mm nodule, as well as multiple peritoneal implants compatible with peritoneal carcinomatosis and a pulmonary nodule in the right upper lobe. With this diagnosis, we decided to apply symptomatic treatment. The patient died 6 months after surgery due to multi-organ failure in the context of sepsis of probable biliary origin.

The incidence of recurrences in the pathway after percutaneous transparietohepatic drainage has been described in 5%–6% of cases; it is an unusual but serious complication.5,6 However, some authors indicate that it could be underdiagnosed. Tumor implants after the placement of a transparietohepatic drain appear to be due to the discharge/release/spill of tumor cells found in the bile fluid,7 which could be closely related to the recurrence of the disease after R0 resection and survival. Even in patients who underwent resection of the tumor implant, early recurrence was the norm in the form of carcinomatosis; therefore, this location is a negative prognostic factor for survival after cholangiocarcinoma recurrence surgery (95% CI 2.32: 1.99–6.13; P<.001). Among the factors related to recurrence, the multivariate analysis shows that lymph node involvement is a negative factor (95% CI 1.29: 1.09–0.154; P=.005); not to mention biliary fistula as a studied factor.8

In order to avoid recurrence, en bloc excision of the drainage path has been proposed during surgery of the primary tumor; however, this can be complex.5 Multiple drains, placement of more than 60 days and the papillary histological type have been described as risk factors for the development of metastatic implants in the transhepatic bile drain pathway.6

Presently, there is controversy over the technique of choice for preoperative biliary drainage in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and se plantea la disyuntiva between transparietal and endoscopic access. Transparietohepatic percutaneous drainage, used until now mostly in Western countries, is an invasive procedure that is not without risks, such as hemobilia, portal thrombosis, development of pseudoaneurysms of the hepatic artery, arterioductal fistula or tumor seeding along the drainage pathway. However, it offers a direct image of the longitudinal tumor extension of the biliary tree. Endoscopic drainage is a less invasive technique that seems to be associated with an increased risk of cholangitis and complications related with the procedure, such as acute pancreatitis or duodenal perforation, which require a greater number of drain tubes and prolongs the time until possible surgery.2,9

On the other hand, more and more Asian groups, predominantly Japanese and Korean, are proposing nasobiliary endoscopic drainage as the first option, since it seems to avoid the possibility of tumor dissemination through the catheter (6%), reducing the risk of iatrogenic vascular injury (8%) during placement, has lower rates of cholangitis (10% vs. 60%; P<.0001) and conversion to another technique (21.7 vs. 95%; P<.005) than classic endoscopic drainage.1,7,9

A meta-analysis has recently been published on 433 patients with biliary drainage in resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma (275 endoscopic drains vs 158 percutaneous drains). In this study, endoscopic bile drainage was associated with higher morbidity (44.3% vs. 22.5%), higher conversion rate to another technique (26.5% vs. 5%), and higher rate of cholangitis (33.8% vs. 7%). However, no significant differences were found in terms of postoperative morbidity and mortality.10

In this context, we can conclude that there is a clear controversy about what should be the access to perform preoperative biliary drainage in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma susceptible to surgical treatment. Nasobiliary drainage, which is gaining popularity among Asian groups, does not seem, at the moment, to be of choice among Western groups.

Please cite this article as: Serrano Hermosilla C, Prieto Calvo M, Gastaca Mateo M, Perfecto Valero A, Valdivieso López A. Recidiva parietal de colangiocarcinoma hiliar. ¿Es el drenaje biliar transparietohepático el de elección en los pacientes con colangiocarcinoma hiliar? Cir Esp. 2020;98:368–370.