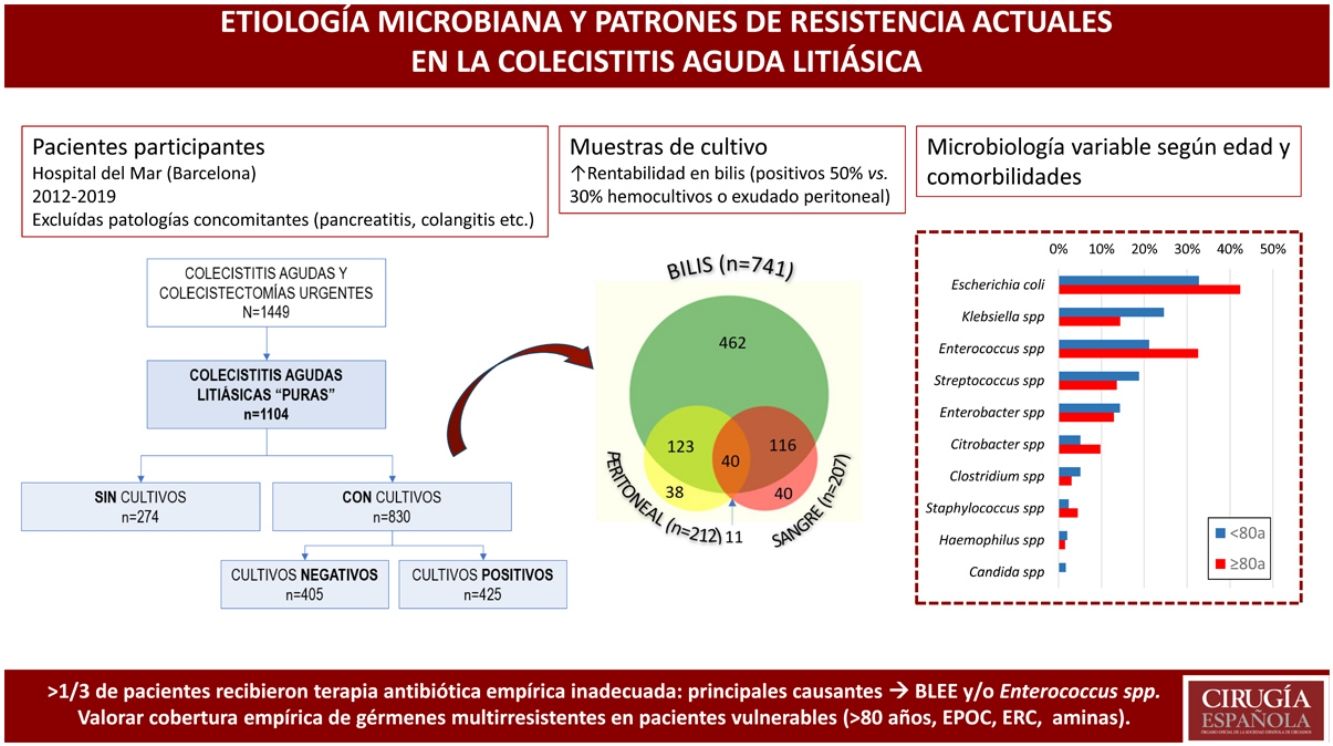

The current treatment for acute calculous cholecystitis (ACC) is early laparoscopic cholecystectomy, in association with appropriate empiric antibiotic therapy. In our country, the evolution of the prevalence of the germs involved and their resistance patterns have been scarcely described. The aim of the study was to analyze the bacterial etiology and the antibiotic resistance patterns in ACC.

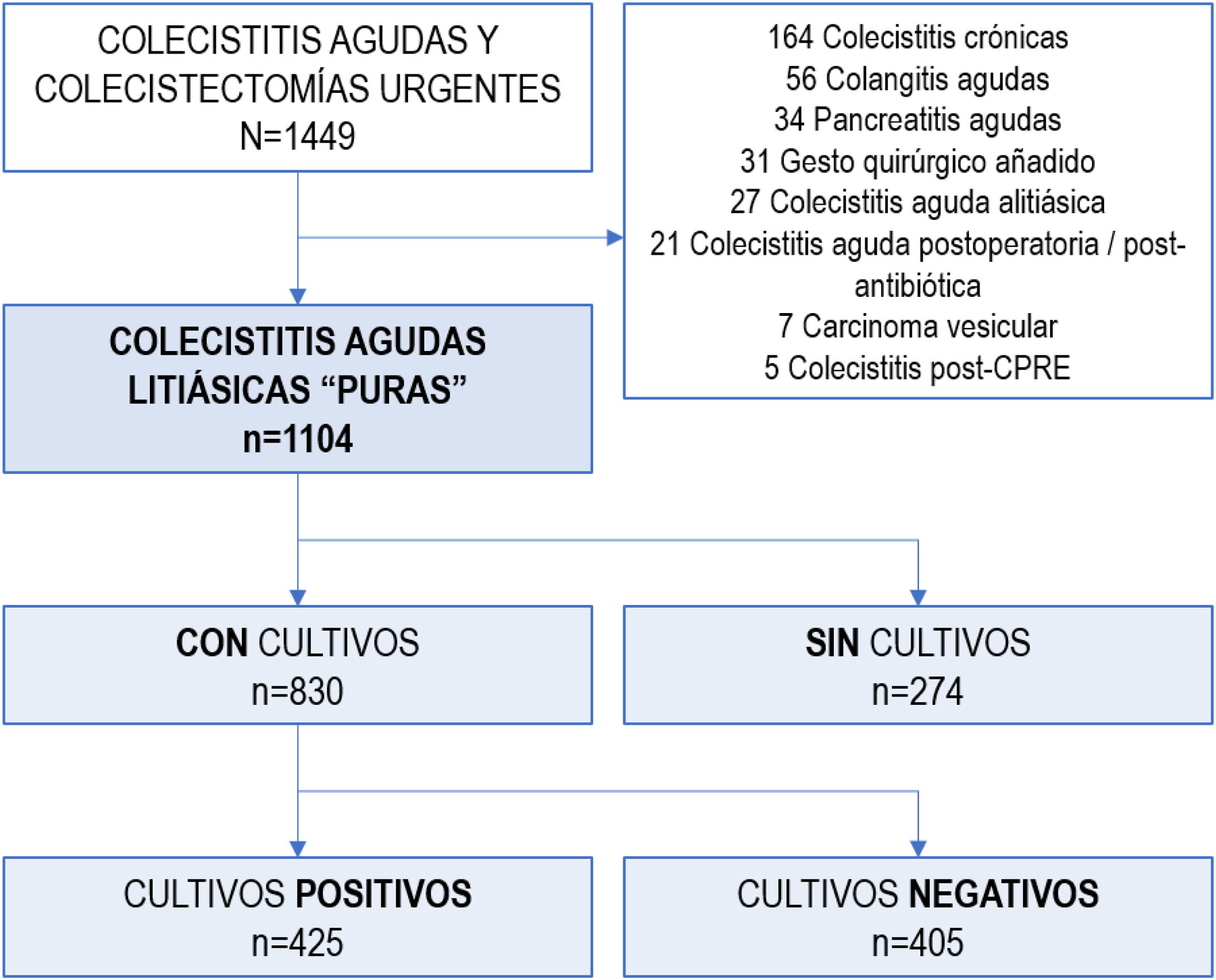

MethodsWe conducted a single-center, retrospective, observational study of consecutive patients diagnosed with ACC between 01/2012 and 09/2019. Patients with a concomitant diagnosis of pancreatitis, cholangitis, postoperative cholecystitis, histology of chronic cholecystitis or carcinoma were excluded. Demographic, clinical, therapeutic and microbiological variables were collected, including preoperative blood cultures, bile and peritoneal fluid cultures.

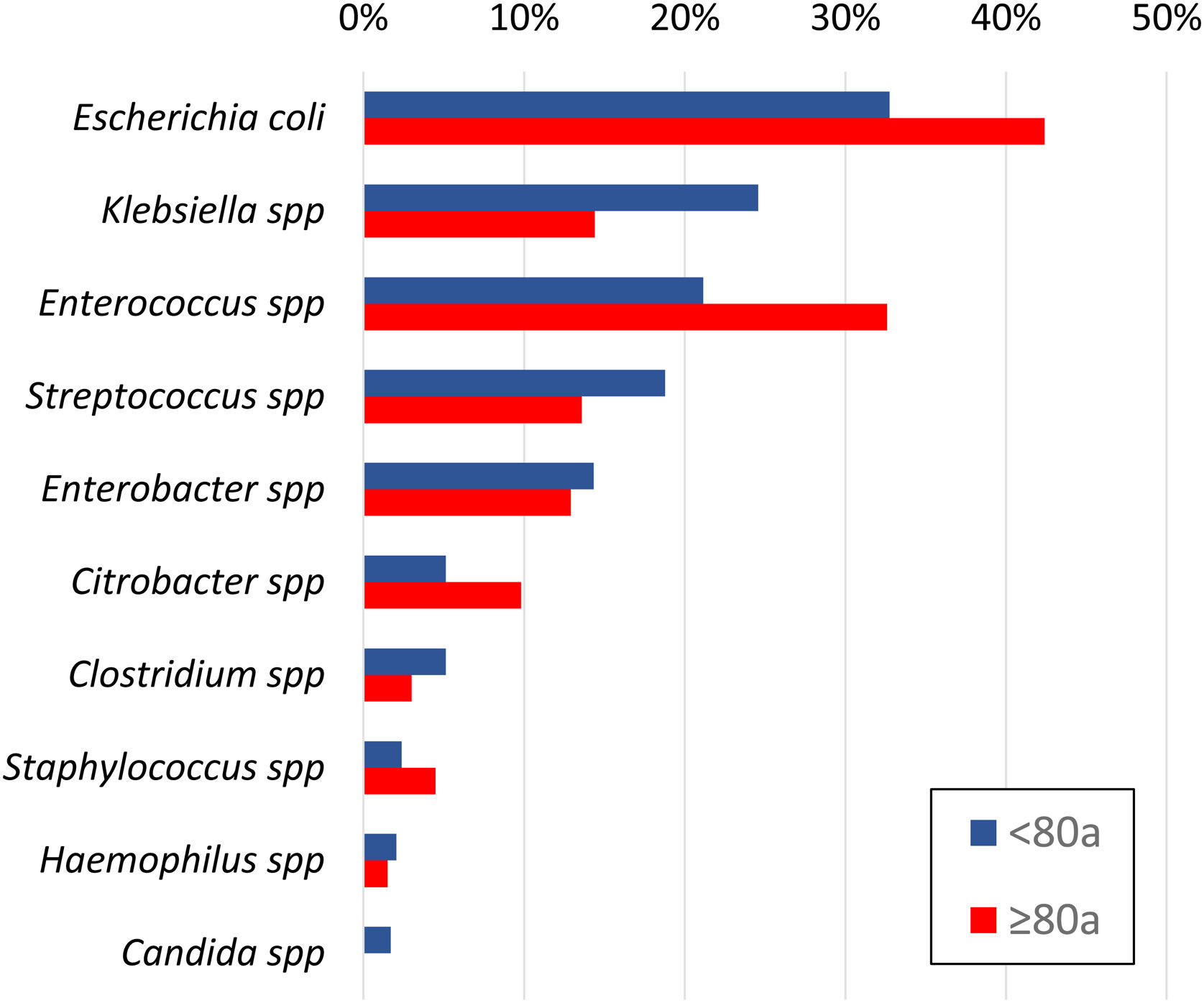

ResultsA total of 1104 ACC were identified, and samples were taken from 830 patients: bile in 89%, peritoneal fluid and/or blood cultures in 25%. Half of the bile cultures and less than one-third of the blood and/or peritoneum samples were positive. Escherichia coli (36%), Enterococcus spp (25%), Klebsiella spp (21%), Streptococcus spp (17%), Enterobacter spp (14%) and Citrobacter spp (7%) were isolated. Anaerobes were identified in 7% of patients and Candida spp in 1%. Nearly 37% of patients received inadequate empirical antibiotic therapy. Resistance patterns were scrutinized for each bacterial species. The main causes of inappropriateness were extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing bacteria (34%) and Enterococcus spp (45%), especially in patients older than 80 years.

ConclusionsUpdated knowledge of microbiology and resistance patterns in our setting is essential to readjust empirical antibiotic therapy and ACC treatment protocols.

El tratamiento actual de la colecistitis aguda litiásica (CAL) es la colecistectomía laparoscópica precoz, asociada a una antibioticoterapia empírica apropiada. La prevalencia de los gérmenes causantes y sus resistencias han sido poco descritas en nuestro medio. El objetivo del estudio fue analizar la etiología bacteriana y sus patrones de resistencia antibiótica en CAL.

MétodosEstudio observacional unicéntrico, retrospectivo, de pacientes consecutivos diagnosticados de CAL en 01/2012-09/2019. Se excluyeron los pacientes con diagnóstico concomitante de pancreatitis, colangitis, colecistitis postoperatoria, estudio anatomopatológico de colecistitis crónica o carcinoma. Se recogieron variables demográficas, analíticas, terapéuticas y microbiológicas, incluyendo hemocultivos preoperatorios, cultivos biliares y de exudado peritoneal.

ResultadosDe un total de 1104 CAL, se tomaron muestras en 830 pacientes: biliares en 89%, de líquido peritoneal y/o hemocultivos en 25%. La mitad de los cultivos biliares y menos de un tercio en sangre y/o peritoneo resultaron positivos. Se aislaron E.coli (36%), Enterococcus spp. (25%), Klebsiella spp. (21%), Streptococcus spp. (17%), Enterobacter spp. (14%) y Citrobacter spp. (7%). Se identificaron anaerobios en el 7% y Candida spp. en 1%. El 37% de los pacientes recibieron una antibioticoterapia empírica inadecuada. Se analizaron detalladamente los patrones de resistencia para cada especie bacteriana. Las bacterias productoras de beta-lactamasas de espectro extendido (34%) y Enterococcus spp. (45%) fueron las principales causantes de la inadecuación, especialmente en pacientes >80 años.

ConclusionesEl conocimiento actualizado de la microbiología y patrones de resistencia en nuestro medio resulta fundamental para reajustar la antibioticoterapia empírica y los protocolos de tratamiento de la CAL.

Acute calculous cholecystitis (ACC) is an acute inflammatory and infectious disease caused mainly by a complication of cholelithiasis. The treatment of choice is early laparoscopic cholecystectomy in association with appropriate empirical antibiotic therapy (EAT). ACC is the second most frequent cause of urgent surgery in our setting.

Among the clinical guidelines pertaining to ACC, the most commonly used are the Tokyo Guidelines from 2018 (TG18), which recommend early surgical treatment of mild and moderate ACC. For severe ACC with failure of at least one organ, less invasive treatment is recommended together with the use of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, metabolic support, and potentially percutaneous or endoscopic gallbladder drainage.1 These guidelines highlight the importance of selecting an appropriate EAT in this era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Meanwhile, they also emphasize the need to monitor local resistance patterns for the prudent use of antimicrobials, facilitate prompt antibiotic de-escalation, and limit the duration of antibiotic regimens to what is strictly necessary.2

In Spain, the recommendations for empirical antibiotic treatment of intra-abdominal infections are 15 years old.3 In intra-abdominal infections like ACC, early control of the focus of infection is essential and can be either total (infected tissue is removed by cholecystectomy) or partial (the gallbladder is drained in patients who are not candidates for initial surgical treatment).4 In patients with more severe ACC who are not candidates for initial cholecystectomy and have a high risk of morbidity and mortality, appropriate EAT is essential for a cure.

Various international publications have reported that the bacteria most frequently isolated in bile samples are enterobacteria, with a slight predominance of Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp.5–7 However, the published series barely cover several hundred patients and frequently group together patients with general biliary pathology, either cholangitis or cholecystitis, both acute and chronic infection, treated with elective or urgent surgery, and cholecystitis of various etiologies.8,9 Thus, the published recommendations offer a wide range of therapeutic possibilities, trying to cover all possible scenarios. As a result, they are inevitably ambiguous and not very specific for the selection of an appropriate EAT in routine clinical practice.

Therefore, to optimize EAT, it is essential to determine the bacterial etiology of the ACC while also considering the local epidemiology to indicate the optimal empirical antibiotic therapy for each case.

The main objective of this study was to describe the bacterial etiology and antibiotic resistance patterns in “pure” ACC in our setting. The secondary objectives were to analyze the appropriateness of empirical antibiotic therapy, as well as the identification of those subpopulations that present a higher risk of developing infections due to multidrug-resistant germs.

MethodsDesign — Patient selectionWe conducted a single-center, retrospective, observational study in the General Surgery Emergency Department of a university hospital in Barcelona (Spain), identifying 1449 consecutive patients diagnosed with ACC between January 2012 and September 2019. The study included 1104 patients with a clinical diagnosis of ACC according to TG18,10 as well as those with a histopathological diagnosis of ACC, focusing the study on patients with “pure” ACC.11 Patients were excluded if they presented concurrent diagnoses, such as: postoperative or postantibiotic cholecystitis, acute cholangitis, acute pancreatitis, acalculous cholecystitis, persistent biliary colic, cholecystitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or definitive pathological diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma (Fig. 1).

VariablesData were extracted from electronic medical records and coded. A total of 134 demographic, analytical, therapeutic and microbiological variables were collected from patients with “pure” ACC (Supplementary Material 1). Preoperative blood cultures as well as intraoperative bile and peritoneal fluid samples (obtained at the discretion of the surgeon) were analyzed.

Microbiological variables included genus and species, as well as Gram stain, oxygen requirements (aerobe/anaerobe) and morphology (cocci, bacilli, coccobacilli). Antibiotic sensitivity was determined for each isolated germ (sensitive, resistant, intermediate, or unknown), and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)–producing bacteria were specifically recorded. The variables were collected in anonymized File Maker v.13™ files (Mountainview, CA, USA).

Estimation of appropriatenessThe antimicrobial treatment was considered appropriate when it was administered at acceptable doses and intervals, with the optimal administration method and following local guidelines and recommendations.3

A germ was considered sensitive to the antibiotic when the minimum inhibitory concentration was lower than the internationally accepted in vitro susceptibility threshold.12 In the case of polymicrobial infections, appropriateness was determined for each of the isolated microorganisms.

When all germs isolated in a patient’s sample were sensitive to the empirical antibiotics received, the antibiotic therapy was considered appropriate. Germs with intermediate sensitivity to the antibiotic administered were coded together with the resistant germs. Thus, treatment of a patient was considered inappropriate when one or more microorganism(s) were either resistant to or showed intermediate sensitivity to the antibiotics administered.

InterventionsAll patients initially received EAT intravenously. Those candidates for treatment with cholecystostomy and/or cholecystectomy received at least one dose before the procedure.

Bile cultures were taken by direct puncture of the gallbladder (cholecystostomy) or by needle aspiration in patients treated surgically, in both laparoscopic and open approaches.

Peritoneal fluid cultures were obtained intraoperatively by direct aspiration of the exudate.

Blood cultures were obtained during hospital admission in patients receiving medical treatment exclusively. Only blood cultures taken prior to the procedure (whether surgery and/or cholecystostomy) were considered in patients undergoing additional treatments apart from antibiotic therapy.

Statistical analysisThe IBM SPSS Statistics v25™ program was used (Rochester, MN, USA).

For the univariate analysis of the association between the qualitative variables, either the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used, and the results were presented as a probability ratio with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

The normality of the distribution of the quantitative variables was estimated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. None of the variables displayed normal distribution, so they were recorded as median and interquartile range (IQR). The comparison between unpaired medians was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Legal and ethical factorsThe study complied with the standards established in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Epidemiology Practice guidelines. The study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Hospital del Mar, Barcelona (reference number: 2020/9312; code: MMP-ANT-2020–01).

ResultsA total of 1104 patients were diagnosed as having “pure” ACC.

Most patients initially received surgical treatment (n = 1044; 94.6%), and 5% required initial conservative treatment (cholecystostomy n = 24, 2.2%; exclusive medical treatment n = 36, 3.3%).

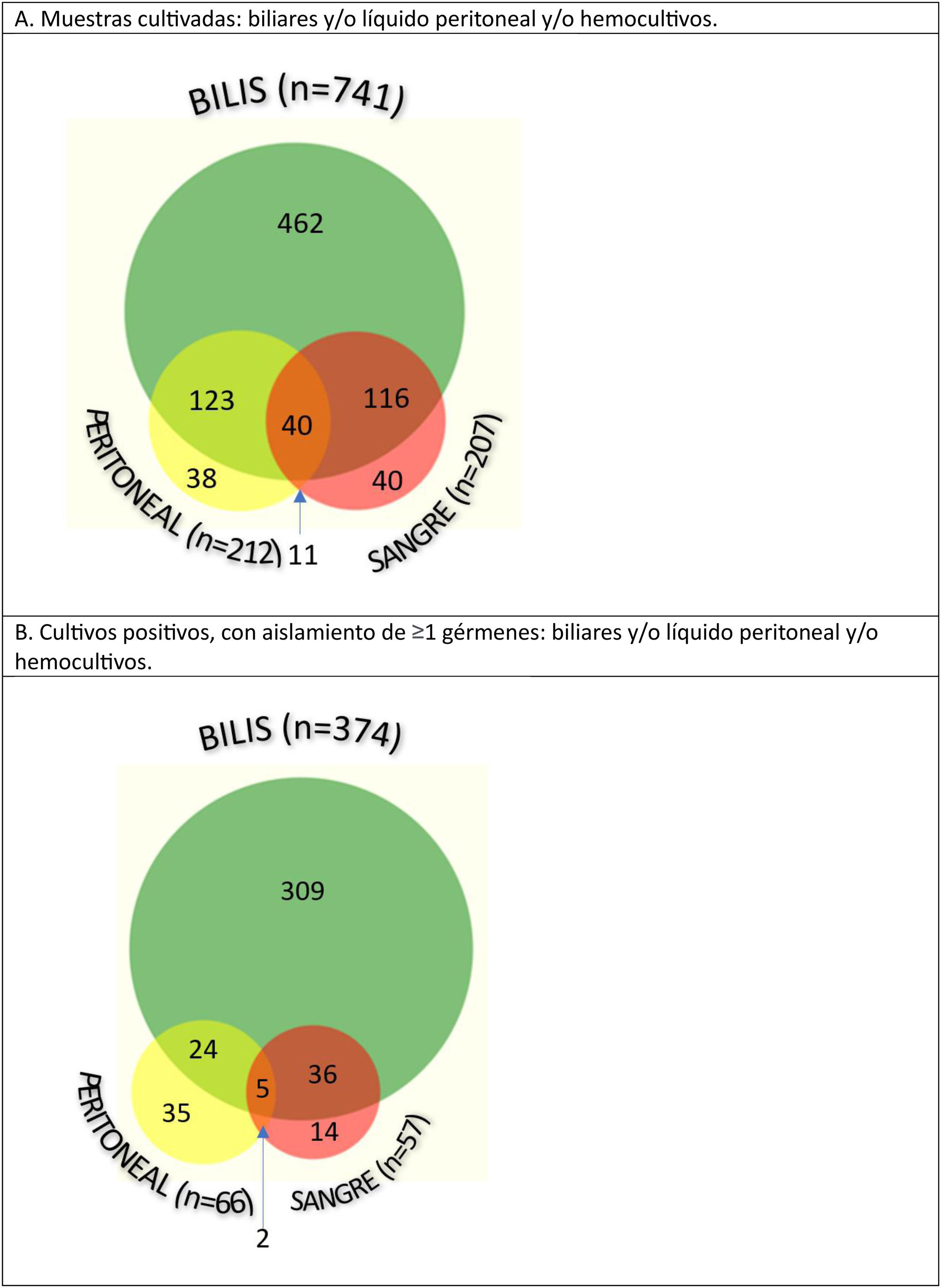

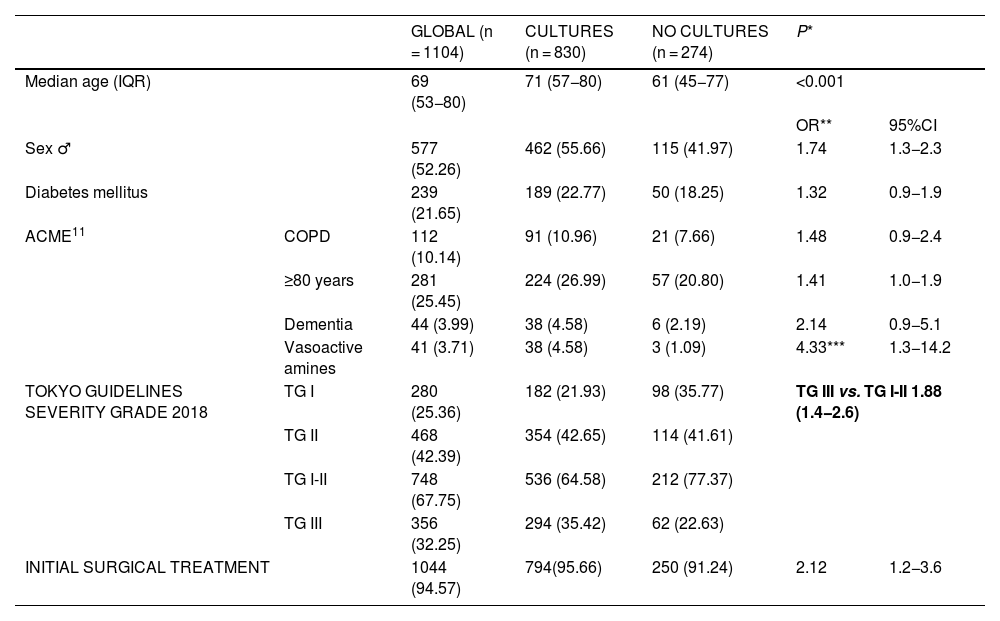

In 830, one or more samples were taken for microbiological cultures: bile cultures in 89% (741/830), and peritoneal fluid samples or blood cultures in 25% of patients (212/830 and 207/830, respectively). Patients from whom samples were taken for culture were more frequently male (55.7% vs. 42%; OR 1.736; 95%CI 1.31–2.28), 10 years older than patients with no cultures (71 vs. 61 years; P < .001), and presented more severe ACC (cultures with TG-III severity 35.4% vs. no cultures with TG-III severity 22.6%; OR 1.876; 95%CI 1.36–2.57) (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of patients with “pure” acute calculous cholecystitis.

| GLOBAL (n = 1104) | CULTURES (n = 830) | NO CULTURES (n = 274) | P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) | 69 (53−80) | 71 (57−80) | 61 (45−77) | <0.001 | ||

| OR** | 95%CI | |||||

| Sex ♂ | 577 (52.26) | 462 (55.66) | 115 (41.97) | 1.74 | 1.3−2.3 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 239 (21.65) | 189 (22.77) | 50 (18.25) | 1.32 | 0.9−1.9 | |

| ACME11 | COPD | 112 (10.14) | 91 (10.96) | 21 (7.66) | 1.48 | 0.9−2.4 |

| ≥80 years | 281 (25.45) | 224 (26.99) | 57 (20.80) | 1.41 | 1.0−1.9 | |

| Dementia | 44 (3.99) | 38 (4.58) | 6 (2.19) | 2.14 | 0.9−5.1 | |

| Vasoactive amines | 41 (3.71) | 38 (4.58) | 3 (1.09) | 4.33*** | 1.3−14.2 | |

| TOKYO GUIDELINES SEVERITY GRADE 2018 | TG I | 280 (25.36) | 182 (21.93) | 98 (35.77) | TG III vs. TG I-II 1.88 (1.4−2.6) | |

| TG II | 468 (42.39) | 354 (42.65) | 114 (41.61) | |||

| TG I-II | 748 (67.75) | 536 (64.58) | 212 (77.37) | |||

| TG III | 356 (32.25) | 294 (35.42) | 62 (22.63) | |||

| INITIAL SURGICAL TREATMENT | 1044 (94.57) | 794(95.66) | 250 (91.24) | 2.12 | 1.2−3.6 | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; ACME, Acute Cholecystitis Mortality Estimation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TG, Tokyo Guidelines *Mann–Whitney U, **Chi-squared, ***Fisher’s exact test (P = .005).

Among the 1160 samples obtained, the most productive cultures were bile cultures, since they were positive in 50.5% of patients (374/741), while in the remaining samples less than one-third of the cultures were positive (66/212 in peritoneal fluid, and 57/207 in blood cultures) (Fig. 2).

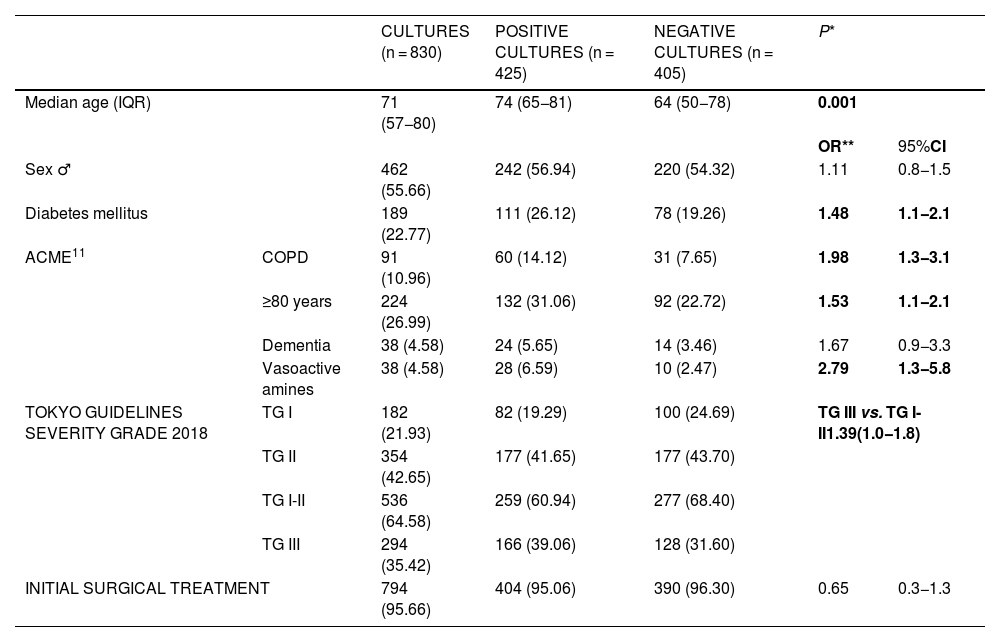

Patients with positive cultures were older (74 vs. 64 years; P < .001), more frequently diabetic (26.1% vs. 19.3%; OR 1.482; 95%CI 1.06–2.05), with chronic obstructive pulmonary pathology (14.1% vs. 7.7%; OR 1.983; 95%CI 1.25–3.13) and presented more severe clinical symptoms (TG-III in patients with positive cultures [39.1%] vs. TG-III with negative cultures [31.6%]; OR 1.387; 95%CI 1.04–1.84) compared to those in whom no germ was isolated in the cultures performed (Table 2).

Characteristics of patients from whom samples were taken (bile and/or peritoneal exudate and/or hemocultures).

| CULTURES (n = 830) | POSITIVE CULTURES (n = 425) | NEGATIVE CULTURES (n = 405) | P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) | 71 (57−80) | 74 (65−81) | 64 (50−78) | 0.001 | ||

| OR** | 95%CI | |||||

| Sex ♂ | 462 (55.66) | 242 (56.94) | 220 (54.32) | 1.11 | 0.8−1.5 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 189 (22.77) | 111 (26.12) | 78 (19.26) | 1.48 | 1.1−2.1 | |

| ACME11 | COPD | 91 (10.96) | 60 (14.12) | 31 (7.65) | 1.98 | 1.3−3.1 |

| ≥80 years | 224 (26.99) | 132 (31.06) | 92 (22.72) | 1.53 | 1.1−2.1 | |

| Dementia | 38 (4.58) | 24 (5.65) | 14 (3.46) | 1.67 | 0.9−3.3 | |

| Vasoactive amines | 38 (4.58) | 28 (6.59) | 10 (2.47) | 2.79 | 1.3−5.8 | |

| TOKYO GUIDELINES SEVERITY GRADE 2018 | TG I | 182 (21.93) | 82 (19.29) | 100 (24.69) | TG III vs. TG I-II1.39(1.0−1.8) | |

| TG II | 354 (42.65) | 177 (41.65) | 177 (43.70) | |||

| TG I-II | 536 (64.58) | 259 (60.94) | 277 (68.40) | |||

| TG III | 294 (35.42) | 166 (39.06) | 128 (31.60) | |||

| INITIAL SURGICAL TREATMENT | 794 (95.66) | 404 (95.06) | 390 (96.30) | 0.65 | 0.3−1.3 | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; ACME, Acute Cholecystitis Mortality Estimation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TG, Tokyo Guidelines. *Mann–Whitney U, **Chi-squared Statistically significant values are shown in bold.

Gram-negative bacilli were identified in 75% of patients, Gram-positive cocci in 43%, and a combination of both in 24%. The isolated flora was polymicrobial in 39% of peritoneal fluid samples, versus 35% of bile samples and 28% of blood cultures.

In the 425 positive cultures, the most frequently identified microorganisms were Escherichia coli (152; 36%), Enterococcus spp (105; 25%), Klebsiella spp (91; 21%), Streptococcus spp (73; 17%), Enterobacter spp (59; 14%), Citrobacter spp (28; 7%) and Clostridium spp (19; 5%). Anaerobic bacteria were isolated in 7.3% and Candida spp in 1% of patients.

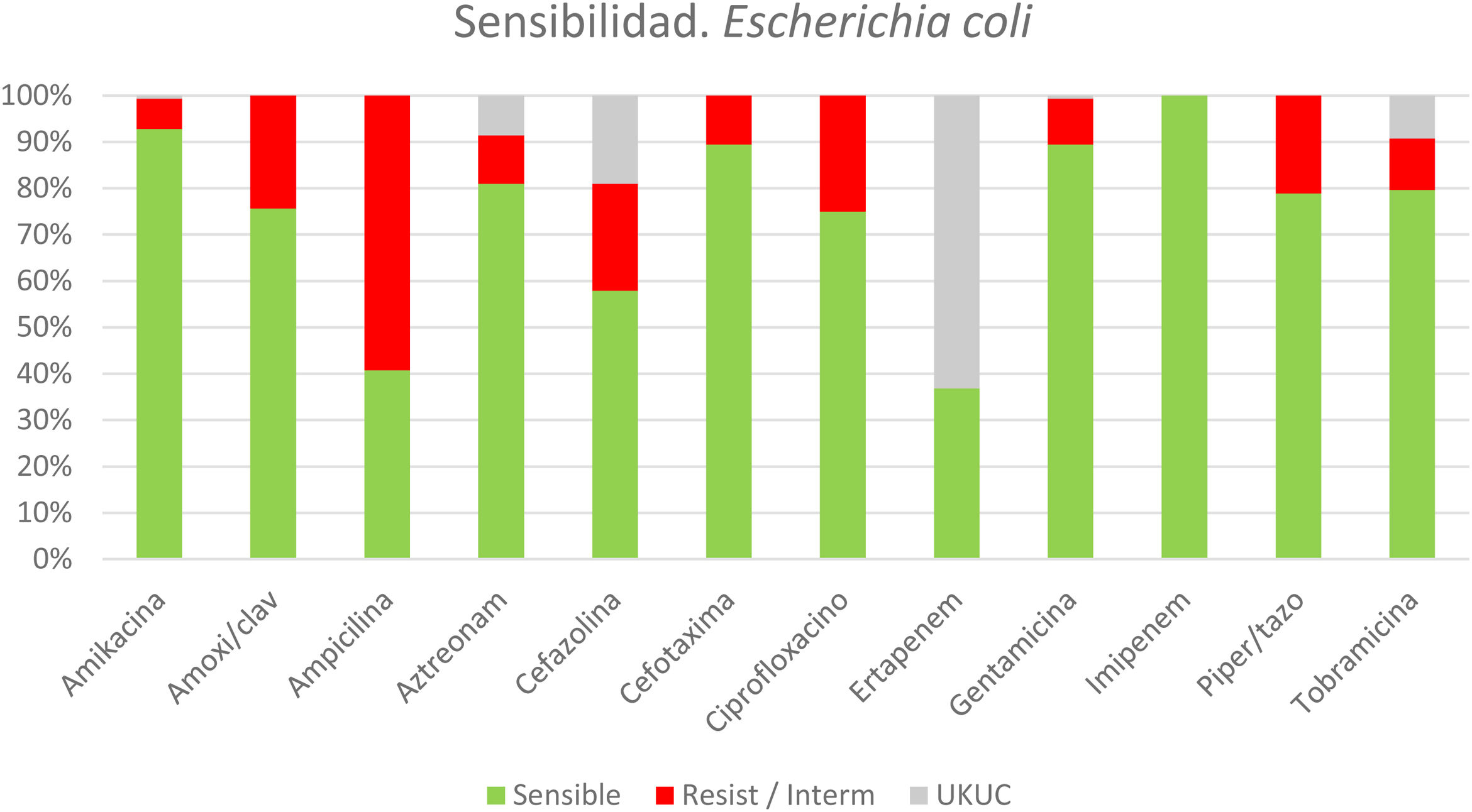

In patients with identified microorganisms, the indicated EAT was analyzed (Fig. 3), revealing that more than one-third of the patients received inadequate initial EAT (158; 37%). The main causes of the inappropriateness of the EAT were ESBL-producing bacteria and/or Enterococcus spp which accounted for 69.6% of the cases of inadequacy. Some 10.5% (16/152) of Escherichia coli isolates were ESBL producers, 5.5% (5/91) of Klebsiella spp, 35.7% (10/28) of Citrobacter spp and 45.8% (27/59) Enterobacter spp. The Enterococcus spp identified were resistant to ampicillin in 18% and vancomycin in 12%.

*Sensitivity/resistance profile of the colibacilli obtained in cultures from patients with acute calculous cholecystitis.

Resist/Interm: resistent or intermediate sensistivity. UKUC: unknown/unclear.

*The sensitivity and resistance panel for E coli was selected, being the most prevalent germ. “Supplementary Material 2” provides the panels of the next 5 most frequently isolated bacteria.

n = 152 patients (out of 425 patients with positive cultures, from a total of 830 cultures)

Patients over 80 years of age had a higher rate of positive cultures compared to younger patients (58.9% vs. 48.3%; OR 1.533; 95%CI 1.12–2.09) (Fig. 4). The prevalence of ESBL and/or Enterococcus spp was greater in patients over 80 years of age (44.7% vs. 29.7%; OR 1.914; 95%CI 1.25–2.92), who received an inappropriate initial APR in almost half of the cases (45% vs. 33% in <80 years; P = .032).

Likewise, in the samples of patients with comorbidities, multiresistant germs (ESBL and/or Enterococcus spp) were isolated more frequently than those without these underlying pathologies, which include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (50% vs. 31.8%; OR 2.147; 95%CI 1.24–3.73) and moderate or advanced chronic kidney disease (54.5% vs. 32.0%; OR 2.548; 95% CI 1.36–4.79). Patients who required perioperative vasoactive amines had a higher prevalence of multidrug-resistant pathogens (53.6% vs. 33%; OR 2.243; 95%CI 1.08–5.07). No differences were found in the isolations of multidrug-resistant germs from patients with or without a history of diabetes mellitus (39.6% vs. 32.5%; OR 1.365; 95%CI 0.87–2.14) or dementia (28% vs. 34.7%; OR 0.73; 95%CI 0.22–2.37).

DiscussionMost of the microorganisms isolated in our series were Gram-positive enterobacteria and cocci, mainly detected in bile samples.

To date, several international groups have published the most frequently isolated microorganisms in bile cultures and ACC. In 2013, Kwon W et al.5 published the largest study of bile cultures published in recent years, including 2217 cultures taken from 1430 patients. However, the authors included patients with acute infection due to bile duct obstruction. Therefore, not only were patients with ACC and associated choledocholithiasis analyzed, but the majority were patients with acute cholangitis who did not necessarily require emergency surgery to resolve their infection. In that study, the most frequently isolated genus was Enterococcus spp, a result that has not been reproduced in similar studies with a smaller number of patients.6,8,9,13 Our study coincides in pointing out the increasing rate of cultures positive for Enterococcus spp (especially in the elderly population) and even resistances to vancomycin or linezolid, which were already identifiable and a cause for concern.

Recently, Jung M Lee et al.7 have published a study where they describe the microbiology found in cultures exclusively from patients with ACC, excluding chronic cholecystitis or malignant pathology. However, the analysis also included patients with associated choledocholithiasis who required prior bile duct manipulation using ERCP or biliary drainage. We consider that the data obtained from these cultures will probably have been altered by this manipulation of the bile duct. Despite this, both this study and ours agree in identifying the main microorganisms isolated, with similar resistance rates, although with lower percentages of the most prevalent germs.

A practical aspect of the current study is the identification of the population subgroup susceptible to presenting ACC due to multi-resistant germs (ESBL and/or Enterococcus spp), with identifiable characteristics in the perioperative study.

Among the factors classically related to infection by multidrug-resistant germs, including ESBL-producing bacteria and enterococcal infections,3,14,15 our series highlights the risk associated with the elderly population over 80 years of age, with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, or the need for vasoactive support. No differences were found in the rates of positive cultures for ESBL-producing germs between patients with or without advanced neurological disease and/or diabetes mellitus. This fact is likely due to the limited number of cases and the fact that the responsible surgeons had already indicated therapies with carbapenems and/or targeted drugs in these patients.

As described by the H Nakai et al. group,16 we should not merely consider ESBL infections in hospitalized patients. Multiple other factors have been described related to the probability of harboring an ESBL infection, which indirectly reflect patient vulnerability.3,14–16 This especially vulnerable subgroup would benefit from initial EAT with very broad-spectrum antibiotics, including carbapenems, avoiding the use of a single EAT for all patients with ACC.

Inappropriate initial EAT has been related to higher morbidity and mortality rates.17 Considering that the main cause of therapy inappropriateness is fundamentally the antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus spp and/or ESBL-producing bacteria, coverage of these multi-resistant germs should be prioritized in the initial therapy administered.

The main limitations of our study lie in its retrospective nature (with the consequent omission of data from the clinical histories), the difficulty to determine the weight of the confounding variables, and ensuring proper sample preservation and transportation. Likewise, previous manipulation of the bile duct has not been recorded in detail, which could alter the prevalence rates of some germs in a small number of patients. Furthermore, the study suffers from bias derived from the fact that cultures were obtained at the discretion of the surgeon. An attempt was made to limit and objectify the magnitude of this bias by comparing the characteristics of patients with and without cultures, which demonstrated that the patients with cultures had more severe ACC.17

In conclusion, more than one-third of the patients in our series had received inappropriate EAT, mainly due to the absence of empirical coverage of ESBL-producing bacteria and Enterococcus spp, particularly prevalent in elderly patients over 80 years of age and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic kidney disease. It is essential to have detailed knowledge about the local microbiology in ACC, as well as its resistance patterns, to better adapt the empirical antibiotic therapy and update treatment protocols.

Conflicts of interestsNone.

FundingNo funding was received.