Primary hepatic leiomyosarcomas (PHL) are malignant mesenchymal tumors derived from smooth muscle cells that are quite rare and difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Their poor prognosis requires R0 resection, which allows us to achieve long-term survival. Here, we present the case of a PHL that was completely resected by hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS).1

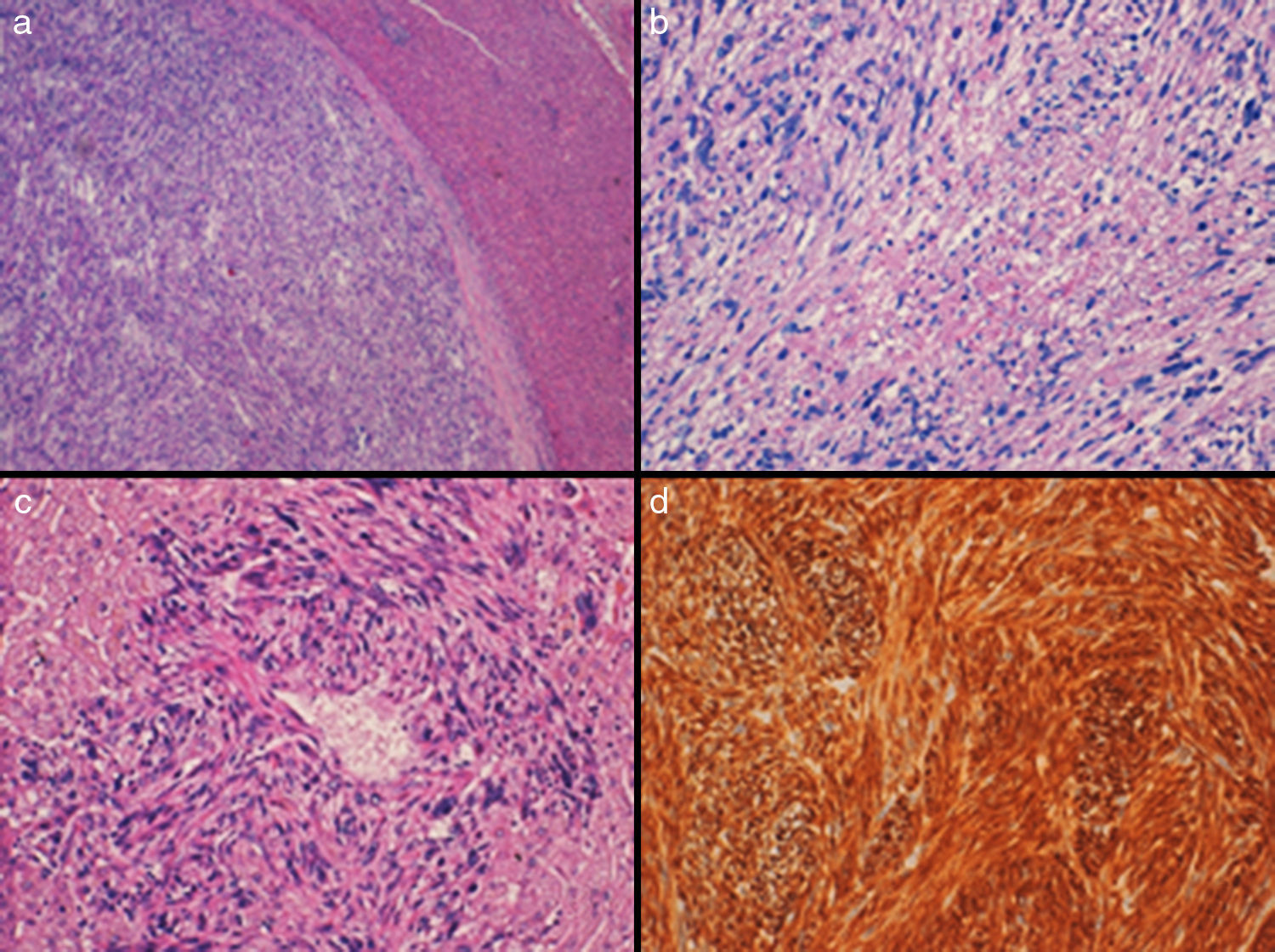

A 63-year-old woman with no prior history of interest reported abdominal pain. Upon examination, a mass was palpated in the epigastrium. Abdominal ultrasound and contrast-enhanced CT scan detected a 7cm mass in the left hepatic lobe, with no evidence of metastatic disease. FNA reported a mesenchymal tumor suggestive of leiomyosarcoma. On PET-CT, the mass was seen to have malignant metabolic characteristics with a maximum SUV of 4.5. We performed HALS and found a 7cm mass in segment III of the left hepatic lobe; segment IV and the rest of the liver parenchyma were normal on intraoperative ultrasound. A laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy was performed without portal occlusion. The surgical time was 120min, and no blood transfusion was required. The patient was discharged 3 days post-op. Microscopically, the hepatic parenchyma was observed to be infiltrated by a malignant mesenchymal neoplasm derived from smooth muscle cells, consisting of bands that crossed in different directions of atypical ovoid or fusiform cells with occasional multinucleated cells (Fig. 1). In addition, areas of necrosis and up to 12 mitotic figures were observed. In the wall of an intrahepatic vessel, these malignant cells were observed to be “emerging” from the wall. The neoplastic cells showed intense cytoplasmic positivity for vimentin, smooth muscle actin and desmin, and negativity for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD-117 (C-Kit), DOG-1 and S-100. The Ki-67cell proliferation index was 20%-30%. The patient did not receive adjuvant treatment and is disease-free 132 months after the intervention.

(a) Solid encapsulated neoplasm that is well outlined from the adjacent liver parenchyma (H-E, 4×); (b) It is constituted by intertwining bundles of spindle cells with marked nuclear atypia, atypical mitotic figures and a focus of necrosis (H-E, 10×); (c) Neoplastic cells emerging from the wall of a small hepatic vessel (H-E, 20×); (d) Intense positivity of tumor cells (desmin 20×).

Hepatic sarcomas are exceptional; they represent 0.1%–1% of primary hepatic malignancies.2 Although angiosarcoma is most frequent, PHL constitutes around 8%–10%.3 Leiomyosarcomas can arise from the muscular walls of intrahepatic vascular structures, bile ducts, or the round ligament. Most hepatic leiomyosarcomas are metastases of leiomyosarcomas from other locations (uterus, retroperitoneum, gastrointestinal tract4); therefore, their exclusion is essential for an accurate diagnosis.

Symptoms are non-specific and frequently include pain in the upper hemiabdomen accompanied by weight loss, low-grade fever, asthenia, jaundice, and even acute intra-abdominal bleeding secondary to tumor rupture. Physical examination may reveal hepatomegaly or an abdominal mass, whereas laboratory data (bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, transaminases, alpha-fetoprotein or other tumor markers) are usually not useful for diagnosis.5

CT usually describes a large heterogeneous, hypodense mass with internal and peripheral enhancement with occasional central necrosis, similar to the findings in our patient.6 MRI showed homogeneous hypointensity in T1 and homogeneous hyperintensity in T2.7

Given the non-specific physical, analytical and radiological data, preoperative histology study (by cytology or ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy) and postoperative histological study are key factors in the diagnosis. Macroscopically, the surface of the cut is usually whitish-pink and yellow, with areas of necrosis or dark red, caused by hemorrhagic foci, and the neoplasm shows a good delimitation from the adjacent liver parenchyma, separated by a capsule-like fibrocollagenous tissue. Histologically, the tumor usually consists of interconnected fascicles of cells with abundant cytoplasm of elongated or ovoid nuclei, with variable atypia; multinucleated cells and cells with vacuolated or eosinophilic cytoplasm can be observed. Mitotic figures are frequent and there is usually necrosis. The histological finding of presence of these neoplastic cells that emerge from the wall of intrahepatic vessels supports their origin in these structures. They express immunohistochemical markers that support the smooth muscle origin, such as smooth muscle actin, desmin and H-caldesmon, and they are negative for other markers, such as CD-117 (C-Kit), DOG-1, S-100, and CKAE1-AE3, which helps exclude other types of neoplasms with which the differential diagnosis is established.8

Treatment consists of hepatic resection with intended R0 resection as the most widely accepted indication. There is no survival of more than 3 years with R1 resections.9 Adjuvant chemotherapy in PHL is not accepted because of the low rate of response, although in advanced stages tumorectomy associated with chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide, or especially irinotecan, are the most accepted options.10 Another alternative is liver transplantation, although it is not recommended because of high rates of recurrence.

HALS and totally laparoscopic surgery are presented as the most appropriate approaches in this type of tumors. In our case, the tumor was 7cm, which is why we were more in favor of using HALS, since the introduction of the left hand allows for manual and ultrasound examination to locate preoperatively undetected lesions in the abdominal cavity, while also providing for the distinction between a primary tumor or the presence of metastatic disease or tumor dissemination throughout the abdominal cavity.

In conclusion, HALS is a safe approach in the treatment of PHL that enables R0 resection with good long-term survival results.

Please cite this article as: López-López V, Robles R, Ferri B, Brusadin R, Parrilla P. Resección laparoscópica asistida de leiomiosarcoma hepático primario: un abordaje seguro en una tumoración infrecuente. Cir Esp. 2017;95:478–480.