The present case reflects our experience in the use of intermittent negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) and instillation of antibiotics in a patient who had undergone several surgeries due to an infected renal hematoma that caused necrotizing fasciitis of the abdominal wall and retroperitoneal space. We believe that the excellent results obtained should promote research of this potentially valuable tool.

The patient is a 58-year-old male who was hospitalized in April 2012 due to urinary sepsis with a right subcapsular renal hematoma after renal biopsy, which was treated conservatively. The patient was rehospitalized on November 2, 2012 due to lower right back pain, arterial hypotension (92/40mmHg), acute renal insufficiency (creatinine: 5.32mg/dl; urea: 230mg/dl) and leukocytosis (21,400μl and neutrophilia). Computed tomography (CT) identified a right perirenal heterogenous collection (8.7cm×6.3cm×15.2cm) between the pararenal fascias that affected the psoas with renal compression, compatible with infected hematoma. Twenty-four hours later, a retroperitoneal percutaneous drain was inserted; 310ml of purulent material was obtained, and imipenem was administered. However, the patient's condition continued to worsen and the CT scan 2 days later showed extensive emphysema suggesting necrotizing fasciitis. Given these radiological findings, urgent exploratory lumbotomy was performed, which identified extensive necrosis of the pararenal fascia. Necrosectomy was performed up to the psoas with partial superior nephrectomy. Intraoperatively, the patient presented mixed shock (septic/hypovolemic) with intraabdominal compartment syndrome, requiring total right nephrectomy followed by embolization of the renal artery due to hemorrhage in the first 24h post-op. The anatomic pathology study identified a club cell tumor (14mm).

The patient was admitted to the ICU on November 6th, and treatment included daptomycin, metronidazole, vancomycin and fidaxomicin due to the development of pseudomembranous colitis (C. difficile) and a positive culture for E. faecium. On November 29, revision surgery was needed because lab work showed that the patient's condition was worsening (leukocytosis; 35,000μl) as well as wound necrosis, at which time continuous negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) was initiated at −125mmHg (VAC®; KCI, Austin, TX, USA). Upon changing the VAC® dressing on December 4th, toxic megacolon and fecal fistula were detected; the procedure was therefore converted to an urgent midline laparotomy that showed fecal peritonitis secondary to cecal perforation. We performed total colectomy and terminal ileostomy. After several dressing changes, on December 28 the VAC® therapy was withdrawn after good progression, which was followed by moist wound care.

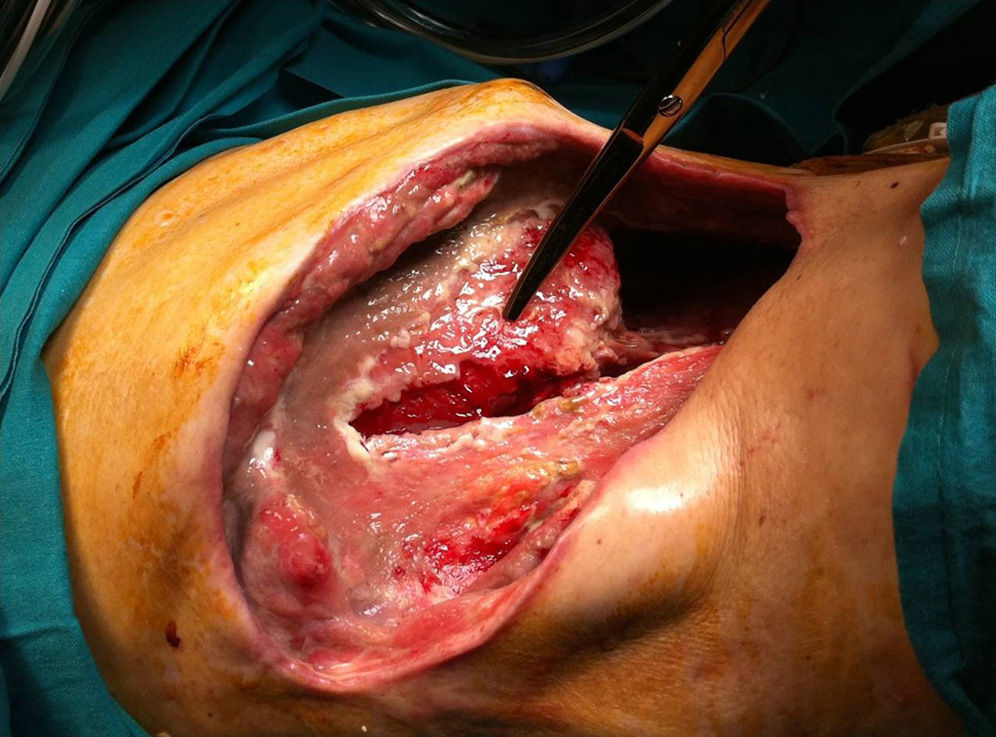

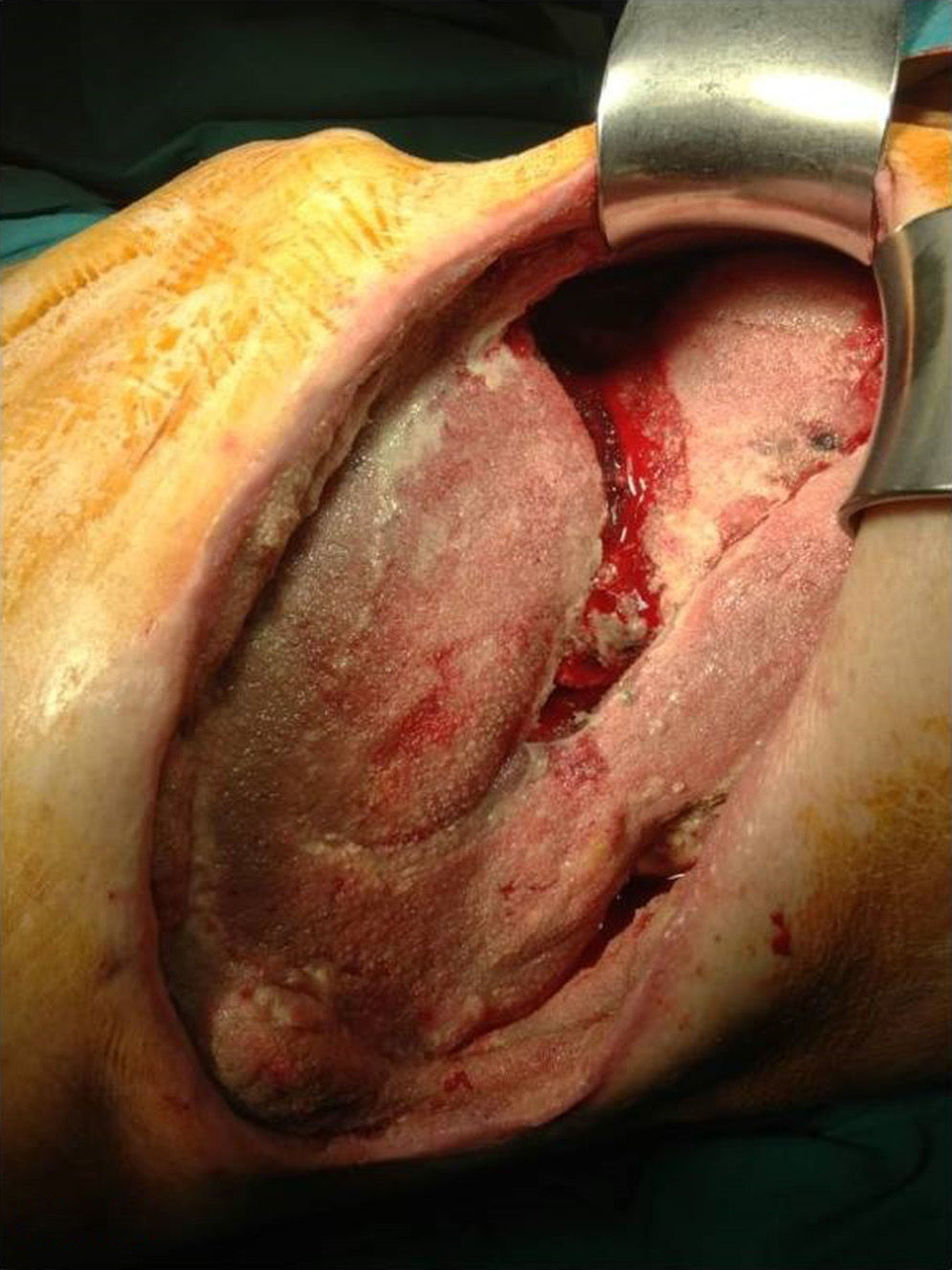

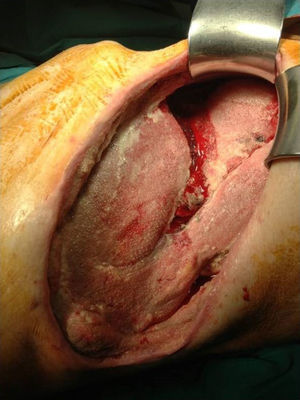

Nonetheless, on January 9, 2013 another revision surgery was necessary due to slow progress. Retroperitoneal fasciitis was identified with myositis of the abdominal wall, an extensive wall defect, and hepatic exposure (Fig. 1). At that time, the patient was treated with meropenem and linezolid, which was changed to ciprofloxacin (400mg/12h for 25 days) due to persistent positive culture for E. faecalis, E. aerogenes and K. pneumonia; teicoplanin (400mg/24h for 35 days) and fluconazole were added because of variation in sensitivity on the antibiogram. Because of the persistence of positive cultures, NPWT was begun on February 7th with instillation of gentamicin (240mg/500ml with a cycle of 3min of irrigation and 2min of aspiration, for 33 days) and later with cefoxitin (same regime for 15 days). After 8 dressing changes, good granulation tissue was obtained over the entire wound surface (Fig. 2). Finally, on March 25th the NPWT was removed, and the abdominal wall was reconstructed with Bio-A® mesh (Gore & Associates, Bio-A® Tissue Reinforcement, USA) with excellent functional recuperation 19 days later.

There are several situations in which the use of NPWT is recommended for its known benefits as it improves tissue perfusion and promotes the formation of granulation tissue and the bacterial inoculum.1 NPWT provides a closed system and eliminates excess fluid to promote wound healing, which is faster and the volume is reduced.2,3 It has been considered the treatment of choice in open abdomen situations for the control of damage and when repeated laparostomy revision surgeries are necessary.4 Furthermore, NPWT (3/2min on–off) seems to obtain peak blood flows that are better and longer lasting. In comparison, the formation of granulation tissue is 63.5% greater, which results in greater endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis.1

Instillation consists of the application of a perforated sponge adapted to the wound with a sealed dressing that covers the extension of the wound and surrounding skin followed by the application of pressure for 2min at −125mmHg and 3-min periods of antibiotic irrigation through the suction tube. Topical antibiotic therapy is controversial, although it is already being applied in many surgical specialties.4–6 The combination of NPWT and irrigation with antibiotics has been described sporadically in the literature. However, it has started to be used in abdominal surgery, and several published reports, such as the D’Hondt et al. case,7 provide encouraging results. The use of this technique could be indicated in abdominal compartment syndrome, postoperative wound suture dehiscence or wall defects secondary to necrotizing fascitis.8

Our team believes that NPWT with the instillation of antibiotics could be indicated in patients with persisting bacterial contamination in spite of adequate systemic antibiotic therapy.7,9 The optimal antibiotics, dosage, and time to initiate instillation will undoubtedly be researched intensively in the near future.

Please cite this article as: Pañella-Vilamú C, Pereira-Rodríguez JA, Sancho-Insenser J, Grande-Posa L. Terapia de presión negativa intermitente con instilación antibiótica en fascitis necrosante de pared abdominal y retroperitoneal secundaria a hematoma renal derecho sobreinfectado. Cir Esp. 2015;93:199–201.