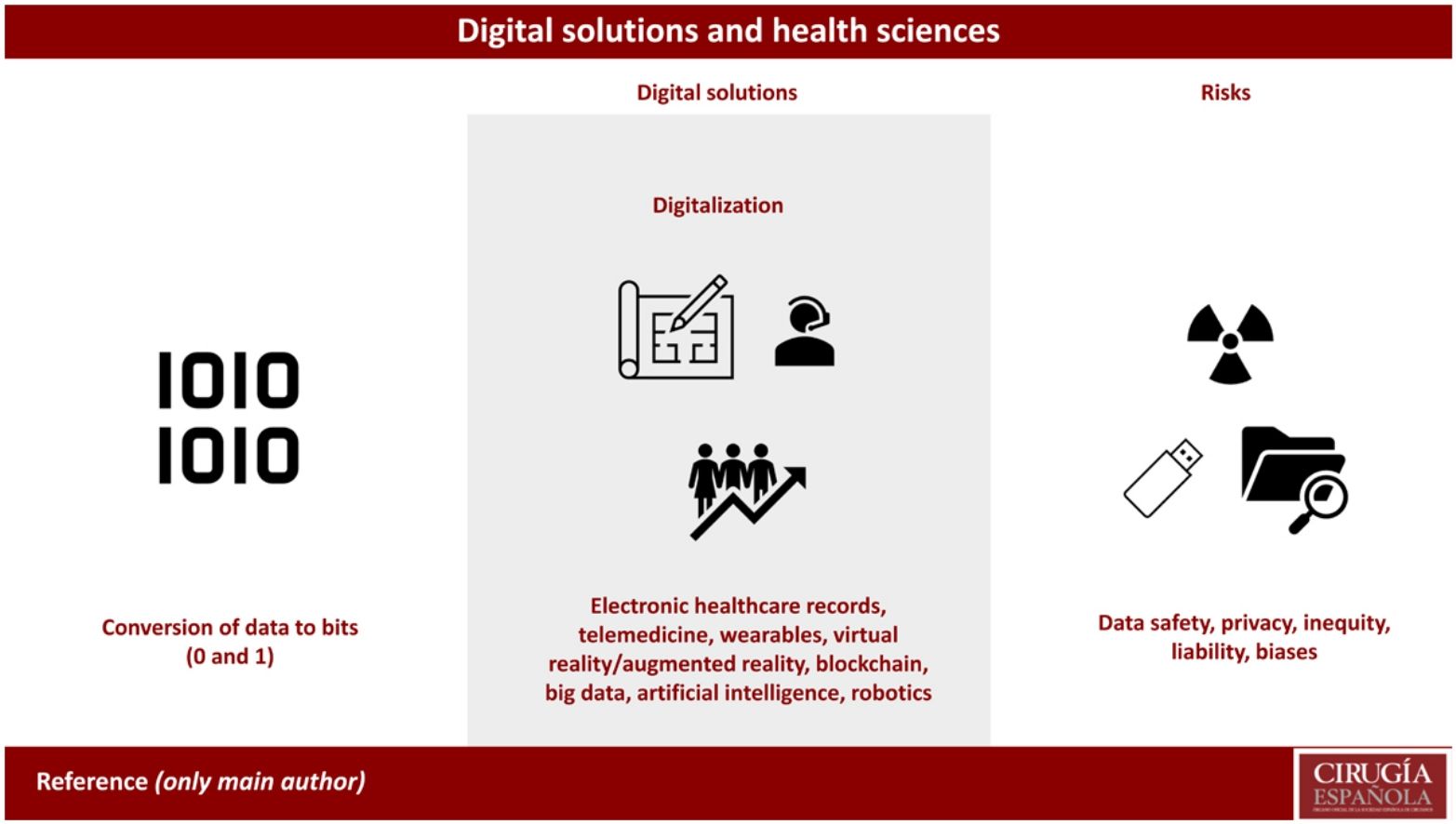

Digitalization is the conversion of analog data and information to a digital format based on bits. Digitalization allows information to be managed in a simple and standardized way. Digital health solutions are technologies that use the digitalization of data and information to improve the health sector in various aspects, such as prevention, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, research, innovation, training, management and evaluation of health services. These technologies range from mobile applications and telemedicine to artificial intelligence and blockchain, with advantages, barriers, and risks for their application in health care.

La digitalización es la conversión de datos e información analógica a un formato digital basado en bits. La digitalización permite gestionar la información de manera sencilla y estandarizable. Las soluciones digitales de salud son tecnologías que usan la digitalización de datos e información para mejorar el ámbito sanitario en diversos aspectos, como la prevención, el diagnóstico, el tratamiento, el seguimiento, la investigación, la innovación, la formación, el entrenamiento, la gestión y la evaluación de los servicios de salud. Estas tecnologías abarcan desde las aplicaciones móviles y la telemedicina hasta la inteligencia artificial y el blockchain, con ventajas, barreras, y riesgos para su aplicación en la asistencia sanitaria.

Digitalization is the process by which analog data and information are transformed into a digital format (binary code, 0 and 1) to form bits, which is the minimum unit of information used in computing. The term was derived from “binary digit”. A bit can only have 2 possible values, 0 or 1, which correspond to the binary states of off or on, false or true, absent or present, etc. One bit can represent a single value or state, but a combination of several bits can represent many more different values or states. For example, 2 bits can represent 4 values (00, 01, 10, 11), 4 bits can represent sixteen values (0000, 0001, …, 1111), and so on. The bits are grouped into larger units to facilitate information management. The most common unit is the byte, which is made up of eight bits and can represent 256 different values. This seemingly simple coding method, digitization, allows you to work with data, information and processes in a simple, standardizable, storable, reproducible and, ultimately, manageable way, using tools or solutions designed to fulfill specific tasks.

Digital health solutions are the set of technologies that take advantage of data digitalization and are applied to the healthcare field1 in order to improve the prevention, diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of diseases; research and innovation; training; management; and evaluation of healthcare services.2 These technologies include everything from information and communication technologies (mobile applications, telemedicine, social media) to wearable devices, artificial intelligence, big data, virtual and augmented reality, or blockchain. All of these have a common basis: the capture, management, analysis and presentation of data in a format that supports decision making by administrators, healthcare professionals and patients.

Without intending to be strictly thorough, this article will review the technological solutions that are the axes and levers of change in the health sciences, with the advantages and challenges of their use, as well as some examples that are currently being implemented.

Electronic health recordsElectronic health record (EHR) systems are digital solutions that provide electronic storage and access to patient care information.3 They are centralized, secure registries of health data that facilitate the exchange of information between professionals, improving the coordination of treatment. Additionally, EHR can offer other functionalities, such as medication alerts, appointment reminders, and advanced data analytics (business intelligence) for clinical decision making. Even so, the use of current EHR models requires that doctors spend a great amount of time dedicated to administrative tasks.

The potential advantages of EHR are limited by a huge barrier, which is interoperability (semantic, technical and organizational), as systems often use different formats and standards, making it difficult to exchange data between them. In addition, the process of copying/pasting information has inherent risks; specifically, many follow-up notes are not original (up to 80% in some systems in the USA), and around 6.5% of clinical notes are included in the wrong patient’s electronic record. Equally concerning is the vulnerability of access to personal data (security and privacy), which requires robust safeguards to protect sensitive patient information. There are already numerous cases of electronic medical history systems that have been “hijacked” by malware, as occurred in 60 NHS trusts with the WannaCry virus.

Regarding legal and ethical risks, incorrect handling of medical data can lead to situations in which patient privacy is at risk through unauthorized or illegitimate access to information. We must remember that the data in medical records belongs to the patients, and, in certain situations, it is necessary to obtain informed consent in compliance with data protection regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union.

The next challenge in Europe is the creation of the European Health Data Space (EHDS), which aims to guarantee and take advantage of the health data of citizens of member states for primary (care) and secondary (research and innovation) use.

TelemedicineTelemedicine is a solution that uses information and communication technologies to provide remote medical care,4 either by telephone, videoconference applications, mobile solutions, or remote monitoring. It enables health professionals to evaluate, diagnose and treat patients while overcoming barriers to access, such as distance. Telemedicine is particularly useful in remote areas, where human and technological resources are not available. Furthermore, it offers the possibility to monitor patients in the long term.

Barriers to telemedicine include the technological or cultural gaps, lack of technological infrastructure in remote areas, limited availability of high-speed internet access, and the resistance to change of certain healthcare professionals. Additionally, telemedicine itself poses challenges, including connection quality, confidentiality of communications, and the difficulty to perform physical examinations remotely.

Legal and ethical risks associated with telemedicine include inappropriate handling of medical data during transmission, professional liability in remote decision making, and protection of patient privacy. It is also important to establish clear guidelines for medication prescriptions and liability in case of errors or complications.

Portable devices (wearables)Wearables are electronic devices that can be worn on the body or clothing that measure and transfer data and information about body functions and activities of the organism.5 The most common types are wearable devices themselves or digital watches that connect to smartphones, which operate as communication platforms linked to storage and processing infrastructures (such as EHR). Potential advantages of using these devices include: improved disease prevention, diagnosis and treatment; patient monitoring; communication between health professionals and patients; and the promotion of healthy lifestyle habits.

However, there are also important barriers that limit the implementation of wearables, such as: the high cost of some devices; the lack of regulation, standardization and scientific validation; and the resistance to change or mistrust of users.

The main risks that may be associated with the use of wearables in health sciences are primarily the dependence upon or addiction to these devices, loss or theft of sensitive information, interference or malfunction of other medical equipment, and possible adverse effects on the physical or mental health of users.

Virtual reality/augmented realityVirtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are technologies that offer immersive and enhanced experiences in different fields, including health. In medicine, VR is used for training healthcare professionals, rehabilitation therapy, and planning of surgical procedures.6 Its maximum application would be the metaverse — a virtual world where our avatars can interact to generate transactions of information for teaching, patient care, research, and management of health sciences. AR, on the other hand, can overlay digital information on the real environment, which can aid in the visualization of anatomical structures during surgery to guide medical procedures.

Some of the barriers to the use of these technologies include the cost of acquiring and maintaining hardware and software equipment, the learning curve for health professionals who must become familiar with these technologies, and the need for adequate infrastructure for their implementation.

The legal and ethical risks of VR and AR in health sciences include the quality and accuracy of simulations, the privacy and security of the medical data used, as well as liability in case of errors or negligence during the use of these technologies in actual+ medical procedures.

BlockchainBlockchain technology works as a distributed ledger system that ensures data integrity and security.7 In healthcare, the use of blockchain can help guarantee the privacy and confidentiality of medical information, enable secure data exchange among healthcare providers, and facilitate the traceability of medical records. Furthermore, blockchain can be used for drug monitoring and pharmaceutical supply chain management.

Barriers to its use include the lack of standardization or widespread implementation of blockchain technology in the healthcare sector, as well as the technical challenges associated with scaling and the performance of blockchains. There are also concerns about data privacy and confidentiality in a distributed blockchain.

Legal and ethical risks include the protection of personal data stored in a blockchain, dispute resolution in case of errors or unauthorized changes in the records, and the compliance with data protection regulations specific to each country.

Big data and artificial intelligenceBig data is a set of data that, due to its volume, velocity of production and variety, cannot be processed using traditional statistical techniques.8 In addition to these three Vs, the fourth and essential is the V for veracity. The data must be reliable and represent reality. These data can be structured (demographic data, laboratory results) or unstructured (clinical notes, images, video, social media). These data, both structured and unstructured, are stored in infrastructures called data lakes. The subsequent analysis of big data using artificial intelligence (AI) tools will potentially revolutionize medicine by facilitating the extraction of knowledge and patterns from large clinical data sets. The available applications include machine learning and deep learning, computer vision, natural language processing (NLP), data/process mining, and robotics, which we will discuss in a separate section.9

In this regard, the emergence of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) or large language models (LLM) is of particular interest, which, through neural networks pre-trained with big data, generate outputs in the form of text or images through a so-called “transformer” architecture. This is the case of GPT (generative pre-trained transformers) and their application as chatbots, such as ChatGPT, which is the fastest-growing technology in history, reaching 100 million users in 2 months.10,11

All of these applications can be used for early disease identification, personalized treatments, prediction of outcomes, improved diagnostic systems, navigation of interventions, research, and training of professionals. Additionally, AI can help automate clinical tasks, such as processing medical images or generating reports.

Barriers include the availability and quality of clinical data, the interoperability of health information systems to collect data from different sources, and the need for accurate and reliable GenAI algorithms that can interpret and extract relevant information from medical data.

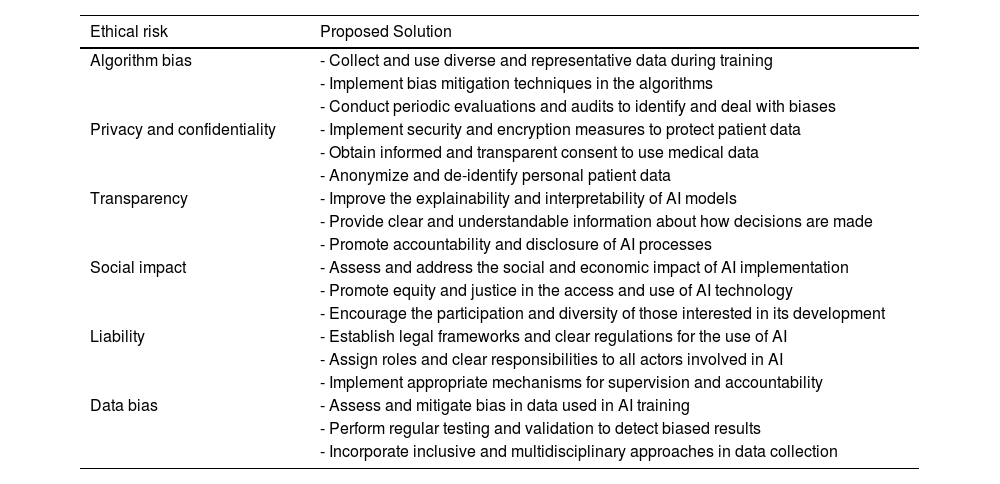

Legal and ethical risks include liability in case of erroneous or biased results generated by AI algorithms, privacy and protection of medical data used in the analysis, and the transparency and explainability of AI models used in clinical decision making.12Table 1 presents a summary of the ethical risks of using AI in health sciences as well as proposals to resolve them.

Ethical risks in the use of AI in health sciences, and proposed solutions.

| Ethical risk | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|

| Algorithm bias | - Collect and use diverse and representative data during training |

| - Implement bias mitigation techniques in the algorithms | |

| - Conduct periodic evaluations and audits to identify and deal with biases | |

| Privacy and confidentiality | - Implement security and encryption measures to protect patient data |

| - Obtain informed and transparent consent to use medical data | |

| - Anonymize and de-identify personal patient data | |

| Transparency | - Improve the explainability and interpretability of AI models |

| - Provide clear and understandable information about how decisions are made | |

| - Promote accountability and disclosure of AI processes | |

| Social impact | - Assess and address the social and economic impact of AI implementation |

| - Promote equity and justice in the access and use of AI technology | |

| - Encourage the participation and diversity of those interested in its development | |

| Liability | - Establish legal frameworks and clear regulations for the use of AI |

| - Assign roles and clear responsibilities to all actors involved in AI | |

| - Implement appropriate mechanisms for supervision and accountability | |

| Data bias | - Assess and mitigate bias in data used in AI training |

| - Perform regular testing and validation to detect biased results | |

| - Incorporate inclusive and multidisciplinary approaches in data collection |

Robotic technologies in healthcare range from surgical robots (decision-making support for surgeons, beyond master-slave platforms) to healthcare assistants, automated drug preparation systems, and devices to aid mobility.13 Although the most popular objective for using robots in healthcare is to increase the precision and effectiveness of surgical interventions, their greatest field of action is patient safety and the performance of repetitive or dangerous tasks, freeing up professionals to focus on more complex, high-value work.

Barriers include the high cost of acquiring and maintaining robots, especially surgical models, as well as the need for specialized training and user skills. In addition, proper integration of robotics into existing healthcare environments is required, although only after reengineering processes to optimize workflows, which can take time and effort.

The legal and ethical risks of robotics in medicine include liability in case of errors or robotic malfunction during procedures, the need for adequate information for patients to give their consent, privacy protection for the medical data used or generated by robots, as well as the lack of equity to access.

ConclusionAdvances made in digital technologies have accelerated over the first 2 decades of the 21st century. However, their appropriate use in the healthcare sector depends on a cultural change and business model that would allow us to overcome the conceptual framework of the industrial revolution, in which “more” is equivalent to “better.” The primary objectives of digital technology must be to increase patient safety while freeing up time for healthcare professionals.

Conflict of interestNone.