Coronary artery perforation associated to cardiac tamponade is an uncommon life-threatening complication of percutaneous coronary intervention, and the occurrence of subepicardial or intramyocardial hematoma without hemopericardium is even rarer.

Clinical caseWe describe the case of a 72 year-old woman with a subepicardial hematoma after percutaneous coronary intervention, who required urgent left internal mammary artery graft to anterior descending artery surgery.

ConclusionsSubepicardial or intramyocardial hematoma must be considered when a coronary perforation is suspected in absence of hemopericardium. Transthoracic echocardiogram or computed tomography may be used to decide a conservative or invasive approach.

La perforación de una arteria coronaria asociada a taponamiento cardiaco es una complicación poco frecuente y potencialmente mortal que puede ocurrir después de un procedimiento coronario percutáneo, siendo aún más rara la aparición de un hematoma subepicárdico o intramiocárdico sin hemopericardio.

Caso clínicoPresentamos el caso de una mujer de 72 años con un hematoma subepicárdico ocurrido después de una intervención coronaria percutánea, quien requirió cirugía coronaria de urgencia con un injerto de arteria mamaria interna izquierda a la descendente anterior.

ConclusionesEl hematoma subepicárdico o intramiocárdico debe ser considerado cuando se sospecha una perforación coronaria en ausencia de hemopericardio. La ecocardiografía transtorácica o la tomografía computada se pueden usar para decidir entre un enfoque conservador o uno invasivo.

Coronary artery rupture associated to cardiac tamponade is an uncommon life-threatening complication of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, and the occurrence of subepicardial or intramyocardial hematoma with or without hemopericardium is even rarer, notwithstanding the presence of extensive antithrombotic therapy.1 These hematomas are reported mostly when treating saphenous vein graft lesions after a coronary artery bypass surgery, and not in elective primary percutaneous angioplasty.2 Although a majority of the perforations are benign and can often be managed conservatively, some can lead to emergency bypass surgery, so the natural course of these events remains unclear.3

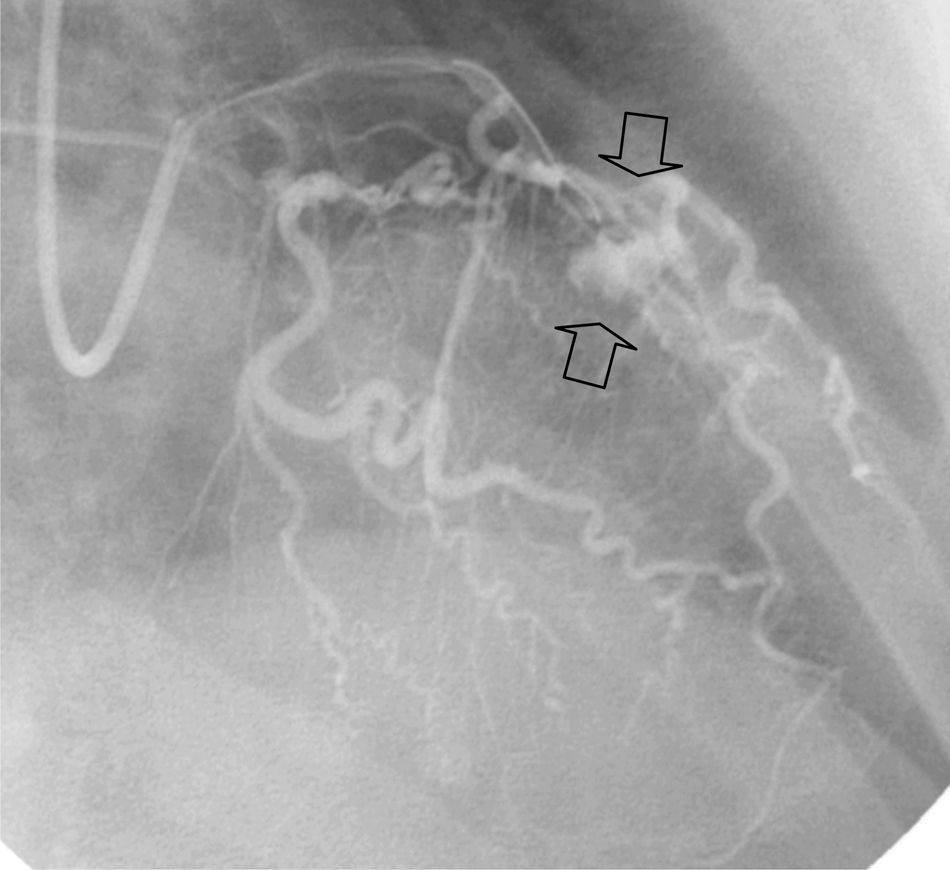

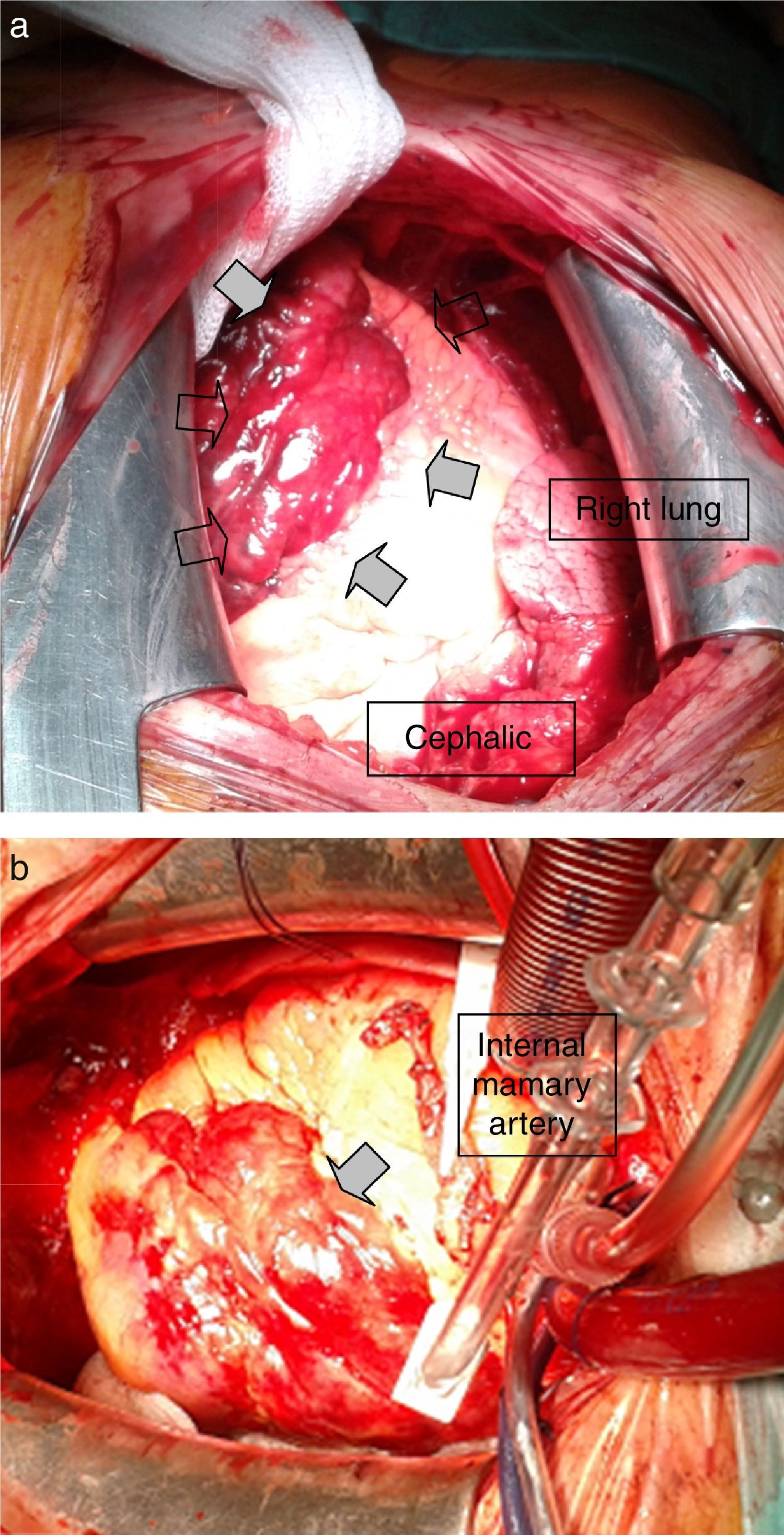

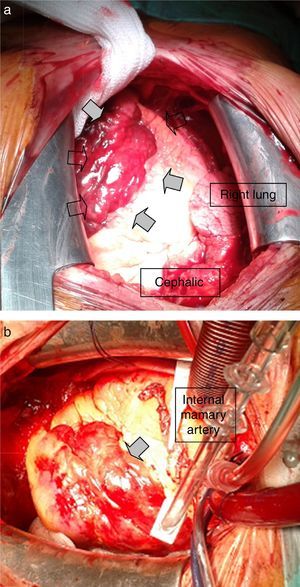

Case reportWe describe the case of a 72 year-old lady with history of arterial hypertension and a femoropopliteal bypass for peripheral vascular disease who was admitted to the coronary care unit because of chest pain with new negative T waves in her electrocardiogram. Coronary angiography depicted severe obstructive disease in left anterior descending and right coronary artery. During the elective percutaneous coronary angioplasty, the patient suffered perforation of the anterior descending coronary artery, with extravasation of contrast (Fig. 1). Initially she was treated conservatively, since neither pericardial effusion nor hematoma was demonstrated in the transthoracic echocardiogram. Six-days later the patient was referred for coronary artery bypass grafting due to angina and two unresolved anterior descending and right coronary arteries stenotic lesions. Intra-operative evaluation showed a large subepicardial and intramyocardial hematoma extensively covering the anterior wall of the heart, without hemopericardium neither pericardial adhesions (Fig. 2). Since the anterior descending coronary artery was not clearly indentified after a wide epicardial incision, an off-pump approach was discarded and an on-pump bypass surgery with the left internal mammary artery graft to anterior descending artery and a saphenous vein graft to right coronary was done. The patient was successfully discharged on the 10th postoperative day and six-months later she remained free of symptoms.

Intramyocardial hematoma is a rare condition associated with myocardial infarction, thrombolytic therapy, chest trauma, and percutaneous coronary intervention, being the last predominantly described in patients with prior coronary artery bypass grafting. There are only a few reports of subepicardial or intramyocardial hematoma without cardiac tamponade presenting as a complication of a primary angioplasty in patients who have not undergone prior cardiac surgery. These few cases were detected immediately after angioplasty because of the patients’ unstable hemodynamic status.4,5 In our case, the patient developed an unstable angina after a conservative management of a failed angioplasty associated to coronary artery perforation. Epicardial hematoma was never suspected, and referral for surgery was based on clinical instability and the two residual stenotic lesions that had to be treated. In our patient, three conventional risk factors of perforation were presented: advanced age, female gender and vessels tortuosity (see Fig. 2a and b).

In patients with prior heart surgery, pericardial adhesions would prevent from cardiac tamponade after a coronary perforation, directing the flow between the epicardial and myocardial layers. In cases with no previous surgery, subepicardial hematoma without pericardial effusion would appear after a complete perforation of an intramyocardial coronary artery, or after an incomplete puncture of an epicardial artery.

ConclusionsSubepicardial or intramyocardial hematoma must be considered when a coronary perforation is suspected in absence of hemopericardium. Transthoracic echocardiogram and computed tomography may be used to decide a conservative or invasive approach. Despite the absence of pericardial effusion, surgical treatment of the hematoma could be indicated in the case of ischemia or infarction secondary to compression of the epicardial artery or hemodynamic instability. Eventually, the immediate implantation of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent to seal the perforation could be a rational alternative treatment to avoid the development of a subepicardial hematoma.

Ethical disclosureProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestNone declared.