Since the introduction of sentinel lymph node biopsy, its use as a standard of care for patients with clinically node-negative cutaneous melanoma remains controversial. Our experience of sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma is presented and evaluated.

Material and methodsA cohort study was conducted on 69 patients with a primary cutaneous melanoma and with no clinical evidence of metastasis, who had sentinel lymph node biopsy from October-2005 to December-2013. Sentinel lymph node biopsy was identified using preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and subsequent intraoperative detection with gamma probe.

ResultsThe sentinel lymph node biopsy identification rate was 98.5%. The sentinel lymph node biopsy was positive for metastases in 23 patients (33.8%). Postoperative complications after sentinel lymph node biopsy were observed in 4.4% compared to 38% of complications in patients who had complete lymphadenectomy.

ConclusionThe sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma offers useful information about the lymphatic dissemination of melanoma and allows an approximation to the regional staging, sparing the secondary effects of lymphadenectomy. More studies with larger number of patients and long term follow-up will be necessary to confirm the validity of sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma patients, and especially of lymphadenectomy in patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Desde la introducción de la biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela, su utilización en pacientes con melanoma cutáneo y ganglios clínicamente negativos permanece controvertido. Hemos evaluado nuestra experiencia en biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela en pacientes con melanoma.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo observacional, en el que hemos estudiado una muestra de 69 pacientes diagnosticados de melanoma cutáneo primario sin evidencia clínica de afectación metastásica, a los que se realizó biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela desde octubre de 2005 hasta diciembre de 2013. El ganglio centinela fue identificado mediante una linfogammagrafía preoperatoria y posterior detección intraoperatoria con sonda gammadetectora.

ResultadosLa tasa de identificación del ganglio centinela fue del 98.5%. El ganglio centinela fue positivo en 23 pacientes (33.8%). Las complicaciones postoperatorias después de la biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela fueron observadas en el 4.4%, frente al 38% de los pacientes sometidos a linfadenectomía.

ConclusiónLa biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela en pacientes con melanoma proporciona valiosa información sobre las vías de diseminación linfática del tumor, y también permite una aproximación a la estadificación regional del mismo, evitando los efectos secundarios de la linfadenectomía. No obstante, serían necesarios estudios de mayor tamaño muestral y tiempo de seguimiento para confirmar la validez de la técnica de la biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela en pacientes con melanoma, y especialmente de la linfadenectomía en casos de ganglio centinela positivo.

The incidence of melanoma has greatly increased over the last 50 years. In 2012 there were 160,000 new cases of melanoma worldwide (3600 in Spain) and approximately 41,000 patients worldwide died as a consequence of this disease (710 in Spain).1

Since its introduction in 19922 the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma care remains controversial and is not included in most European clinical guidelines for the management of melanoma.3 However, this procedure has become a habitual practice for the staging and treatment of ≥1mm clinically node-negative melanomas or melanomas <1mm thick associated with factors of poor prognosis. This threshold aside, the predicted number of positive sentinel lymph nodes is too low to justify the use of this technique.

The main objective of sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma is early identification of patients with clinically occult nodal metastasis, who might benefit from a lymphadenectomy. Many studies have shown that sentinel lymph node status is an independent prognostic factor in relation to overall survival and disease-free survival of patients with melanoma.4–6 Its predictive value is greater than the usual prognostic factors, such as Breslow thickness, Clark level, the presence of ulceration, gender and age.7 Furthermore, the information obtained regarding the lymph status is essential both for accurate AJCC staging6 and decisions regarding possible adjuvant treatments. However, many authors do not recommend routine use of this technique, basing their arguments on results such as those of the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT),8 which did not show any significant differences in survival between patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy (and immediate lymphadenectomy if the result was positive for metastasis) and those patients evaluated only by observation and with lymphadenectomy if lymph node recurrence resulted. Other retrospective studies have revealed similar results and the outcome of sentinel lymph node biopsy and of lymphadenectomy in long-term patient survival together with their therapeutic contribution is currently under debate.9

In our hospital we have a multidisciplinary team for the management of melanoma, which includes the following services: Nuclear Medicine, Dermatology, General Surgery, Pathological Anatomy and Oncology. We perform between 5 and 10 sentinel lymph node biopsies in melanoma patients per year and our experience spans 8 years of using this technique. In cases of sentinel lymph node metastasis a lymphadenectomy of the affected lymphatic area is performed.

The aim of our study was to evaluate all patients with melanoma treated in our hospital using sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Material and methodsAn observational retrospective study was conducted, which included all patients with melanoma on whom sentinel lymph node biopsy had been performed in the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón from 1st October 2005 to 1st December 2013.

The selection criterion for performing sentinel lymph node biopsy was as follows: all patients with ≥1mm with no palpable lymphatic nodes or distant metastasis. Patients with melanomas<1mm were also included in the study if they presented with poor prognostic factors such as Clark level V or the presence of ulceration/regression in anatomopathological analysis.

The following data were collected for each of the patients: gender, age, location and histological type of primary lesion, Breslow thickness, Clark level, location, number and status of sentinel lymph node, lymphadenectomy results if appropriate, presence of ulceration, mitotic index, presence of perineural or vascular invasion, presence of inflammatory infiltration, adjuvant treatment, side effects of sentinel lymph node or lymphadenectomy, the presence of (local or distant) recurrence and survival.

Lymphoscintigraphy and surgical sentinel lymph node techniqueOn the morning of surgery lymphoscintigraphy was performed by injecting 37MBq of Tc99m-nanocolloid human serum albumin (Nanocoll®) in 0.4ml intradermally in 4-quadrant fashion around the periphery of the primary lesion or biopsy scar.

A Philips Skylight conventional 2-headed gamma camera with low energy and high resolution collimators was used to obtain the images. Dynamic and static images were obtained, beginning with dynamic images 5–10min after injection of the radiotracer and obtaining static images every 20–30min thereafter until the sentinel lymph node was visualised.

Surgery took place the same morning and for the intraoperative location of the sentinel lymph node a gamma probe was used (Europrobe®, Eurorad, Strasbourg, France), handled by an experienced nuclear medicine physician. All nodes presenting with radioactive activity measured by the gamma probe as larger than 10% of the node with greater activity ex vivo were removed; all measurements were taken per second. All extirpated nodes were placed in recipients for individual examination. A thorough search for any radioactive activity in the surgical site was carried out to finalise the procedure and once it had been confirmed that no deposit activity exceeded 10% of the sentinel lymph node, the procedure was terminated.

Anatomopathological analysis of the sentinel lymph nodeHistological analysis involved resecting the node as a whole by 2mm cross-section cuts which were then dyed using haematoxylin-eosin and immunohistochemistry staining was performed (S100, HMB45, MelanA).

Surgical and adjuvant treatmentLymphadenectomy was performed on patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes if baseline patient conditions allowed it. Adjuvant treatment with interferon was offered to patients with stage IIB melanoma with positive resected sentinel lymph nodes.

Follow-upPatient follow-up consisted of a thorough clinical examination in the Dermatology unit once a month for 3 months and then every 6–12 months, depending on the patient's condition, for an indefinite period. Disease recurrence and survival status was obtained from the computerised clinical records of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was based on Pearsons χ2 test or the exact Fisher test for qualitative data analysis, and on the Student t-test for quantitative analysis, and log-rank analysis. Logistic step-by-step regression analysis was used. Access 7.0 was used for data management and mathematical calculations were made using the SPSS 20.0 statistical programme for Windows. The significance level was determined at P<0.05.

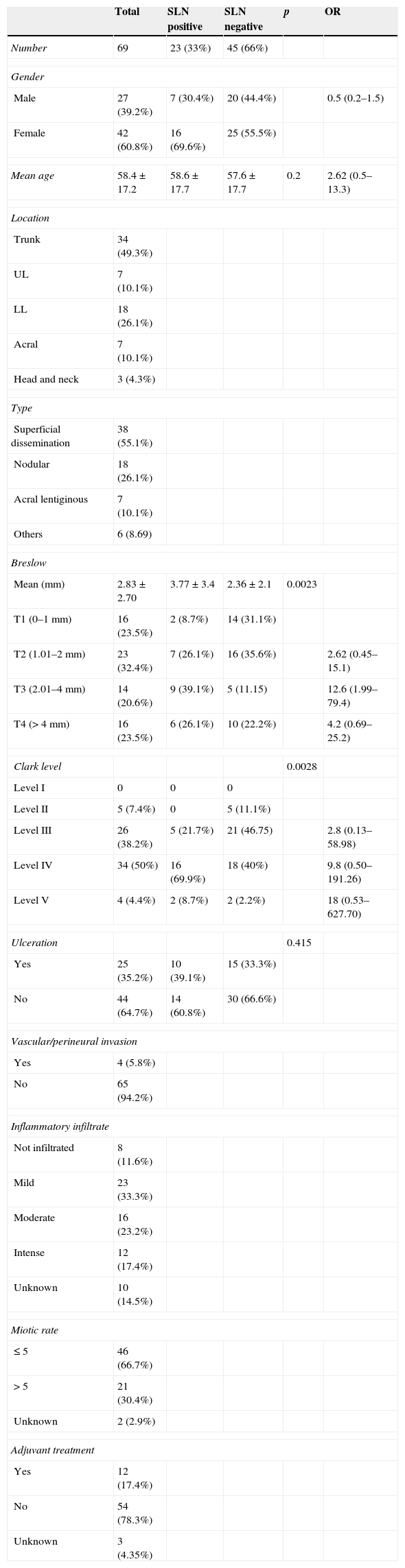

ResultsFrom October 2005 to December 2013, sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed on 69 patients with melanoma. 42 were female (60.8%) and 27 were male (39.2%). The mean age of patients was 58.4 year-old. Clinical and histological characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Clinico-pathological sample factors.

| Total | SLN positive | SLN negative | p | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 69 | 23 (33%) | 45 (66%) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 27 (39.2%) | 7 (30.4%) | 20 (44.4%) | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) | |

| Female | 42 (60.8%) | 16 (69.6%) | 25 (55.5%) | ||

| Mean age | 58.4±17.2 | 58.6±17.7 | 57.6±17.7 | 0.2 | 2.62 (0.5–13.3) |

| Location | |||||

| Trunk | 34 (49.3%) | ||||

| UL | 7 (10.1%) | ||||

| LL | 18 (26.1%) | ||||

| Acral | 7 (10.1%) | ||||

| Head and neck | 3 (4.3%) | ||||

| Type | |||||

| Superficial dissemination | 38 (55.1%) | ||||

| Nodular | 18 (26.1%) | ||||

| Acral lentiginous | 7 (10.1%) | ||||

| Others | 6 (8.69) | ||||

| Breslow | |||||

| Mean (mm) | 2.83±2.70 | 3.77±3.4 | 2.36±2.1 | 0.0023 | |

| T1 (0–1mm) | 16 (23.5%) | 2 (8.7%) | 14 (31.1%) | ||

| T2 (1.01–2mm) | 23 (32.4%) | 7 (26.1%) | 16 (35.6%) | 2.62 (0.45–15.1) | |

| T3 (2.01–4mm) | 14 (20.6%) | 9 (39.1%) | 5 (11.15) | 12.6 (1.99–79.4) | |

| T4 (>4mm) | 16 (23.5%) | 6 (26.1%) | 10 (22.2%) | 4.2 (0.69–25.2) | |

| Clark level | 0.0028 | ||||

| Level I | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Level II | 5 (7.4%) | 0 | 5 (11.1%) | ||

| Level III | 26 (38.2%) | 5 (21.7%) | 21 (46.75) | 2.8 (0.13–58.98) | |

| Level IV | 34 (50%) | 16 (69.9%) | 18 (40%) | 9.8 (0.50–191.26) | |

| Level V | 4 (4.4%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (2.2%) | 18 (0.53–627.70) | |

| Ulceration | 0.415 | ||||

| Yes | 25 (35.2%) | 10 (39.1%) | 15 (33.3%) | ||

| No | 44 (64.7%) | 14 (60.8%) | 30 (66.6%) | ||

| Vascular/perineural invasion | |||||

| Yes | 4 (5.8%) | ||||

| No | 65 (94.2%) | ||||

| Inflammatory infiltrate | |||||

| Not infiltrated | 8 (11.6%) | ||||

| Mild | 23 (33.3%) | ||||

| Moderate | 16 (23.2%) | ||||

| Intense | 12 (17.4%) | ||||

| Unknown | 10 (14.5%) | ||||

| Miotic rate | |||||

| ≤5 | 46 (66.7%) | ||||

| >5 | 21 (30.4%) | ||||

| Unknown | 2 (2.9%) | ||||

| Adjuvant treatment | |||||

| Yes | 12 (17.4%) | ||||

| No | 54 (78.3%) | ||||

| Unknown | 3 (4.35%) | ||||

SLN: sentinel lymph node; LL: lower limbs; UL: upper limbs; OR: odds ratio; p: statistical significance.

The rate of overall identification of the sentinel lymph node was 98.5% (68 patients). In one patient who presented with a tumour in the left breast no lymphatic migration was detected on the radiotracer in the lymphoscintigraphy prior to surgery nor were any sentinel lymph nodes detected intraoperatively. A total of 164 lymph nodes were resected, the mean number of sentinel lymph nodes removed being 2.37. In 33% of cases only one sentinel lymph node was removed, with detection of the node in the following areas: unilateral axilla (33 cases, 47.8%), bilateral axillae (one case, 1.4%), unilateral groin (27 cases, 39.1%), bilateral groins (one case, 1.4%), bilateral groins and bilateral axillae (2 cases, 2.9%), unilateral head and neck area (3 cases, 4.3%), bilateral head and neck area (2 cases, 2.9%). The drainage area for limb melanomas was always homolateral. Drainage to multiple node fields was present in 5 cases (7.1%), all of which were from dorsal melanomas.

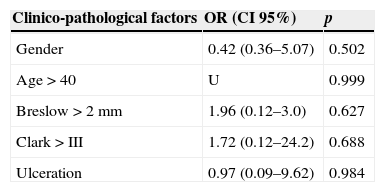

Of the 68 patients with sentinel lymph nodes, 23 (33.8%) tested positive for metastasis. With regards to the predictive factors of metastatic involvement of the sentinel lymph node, although an increase in risk relating to the proportional involvement of the Beslow thickness and Clark level was observed, no statistical significance was found in either the univariate (Table 1) or the multivariate analysis (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis of clinico-pathological factors for predicting sentinel lymph node involvement.

| Clinico-pathological factors | OR (CI 95%) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.42 (0.36–5.07) | 0.502 |

| Age>40 | U | 0.999 |

| Breslow>2mm | 1.96 (0.12–3.0) | 0.627 |

| Clark>III | 1.72 (0.12–24.2) | 0.688 |

| Ulceration | 0.97 (0.09–9.62) | 0.984 |

SLN: sentinel lymph node a; CI: confidence interval; U: unknown; OR: odds ratio; p: statistical significance.

Lymphadenectomy was performed on 78% (18 out of 23 patients) of the patients with positive sentinel lymph node results. 5 patients with positive sentinel lymph node results were not indicated for lymphadenectomy due to baseline patient conditions and no local or distant recurrence occurred in any of them. Only 2 of the 18 patients (11%) on whom lymphadenectomy was performed presented with metastasis to other lymph nodes, with a Breslow thickness of 15.2mm and 2.77mm, respectively. Of patients with positive sentinel lymph node results, 47% were treated with high-dose interferon alfa2b for a year (Kirkwood guideline). One patient (4.6%) with negative sentinel lymph node results but with negative prognostic factors (stage IIb) was treated with interferon alfa2b.

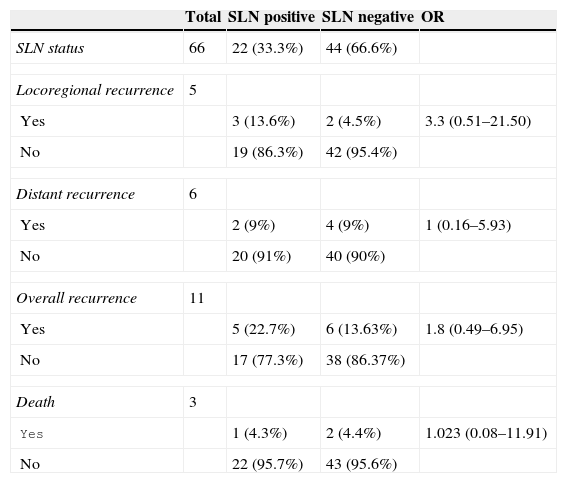

Mean patient follow-up was for a 95 month period (ranging between 7 and 100 months). Two follow-up cases were abandoned, one which presented with positive sentinel lymph node results and the other negative. There were 11 cases of recurrence (16.6%), 5 on a locoregional level and 6 on a distant level. In the patient group with positive sentinel lymph node results, 5 (22.7%) of the 22 patients experienced recurrence, 3 on a local level and 2 on a distant level. In the patient group with negative sentinel lymph node results 6 patients (13.63%) experienced recurrence, 2 on a local level and 4 on a distant level, which determined a false negative rate of 9.5% (false negative considered to be the presence of a local recurrence in patients with negative sentinel lymph node results). Notwithstanding, if we also included those patients who had experienced a distant recurrence presenting with negative sentinel lymph node results, the false negative rate would increase up to 13.6%. Of the 18 patients with positive sentinel lymph node results who underwent lymphadenectomy, 3 (16%) experienced local level recurrence. In our sample, although there is a percentage variance in recurrence between patients with positive sentinel lymph node results to those with the negative sentinel lymph node results (OR=1.8; Table 3), no statistical significance occurred here.

Analysis of recurrences and death depending on the status of the sentinel lymph node.

| Total | SLN positive | SLN negative | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLN status | 66 | 22 (33.3%) | 44 (66.6%) | |

| Locoregional recurrence | 5 | |||

| Yes | 3 (13.6%) | 2 (4.5%) | 3.3 (0.51–21.50) | |

| No | 19 (86.3%) | 42 (95.4%) | ||

| Distant recurrence | 6 | |||

| Yes | 2 (9%) | 4 (9%) | 1 (0.16–5.93) | |

| No | 20 (91%) | 40 (90%) | ||

| Overall recurrence | 11 | |||

| Yes | 5 (22.7%) | 6 (13.63%) | 1.8 (0.49–6.95) | |

| No | 17 (77.3%) | 38 (86.37%) | ||

| Death | 3 | |||

| Yes | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (4.4%) | 1.023 (0.08–11.91) | |

| No | 22 (95.7%) | 43 (95.6%) | ||

SLN: sentinel lymph node; OR: odds ratio.

Overall mortality of the sample was 5.79%; there were 3 deaths (4.3%) caused by melanoma, one in the group with positive sentinel lymph node results (mortality rate of 4.3%) and the other 2 in the group with negative sentinel lymph node results (mortality rate of 4.4%).

Post-operative complications from sentinel lymph node biopsy were observed (seroma, infection) in 4.4% (3/68) of patients. This compared with the complications in 38% (7/18) of those patients with positive sentinel lymph node results who underwent lymphadenectomy (lymphoedema, lymphocele seroma, infection) (OR=0.07; P=0.0005). These differences were statistically significant.

DiscussionIn our study the percentage of positivity of the sentinel lymph node was 33.8%, which is above that of other studies where it ranged between 15% and 23%.6,8,10–12 Of those patients who underwent lymphadenectomy, subsequent to a positive sentinel lymph node result, 11% presented with other non-sentinel lymph node involvement. This result was comparable to other series where the percentage ranged from 7.8% to 33%.5,6,13 The low incidence of positivity in non-sentinel lymph nodes removed in lymphadenectomy is notable in our study (11%), and in other studies, which may indicate that this procedure may be unnecessary in patients with thin melanomas,4,14,15 showing that metastasis in these patients is exclusively confined to the sentinel lymph node.

Regarding predictive factors of sentinel lymph node involvement, we found no statistical significance in the univariate analysis for Beslow thickness or Clark level, in contrast to other studies.16,17 We did, however, observe a tendency for an increase in the OR for metastasis involvement of the sentinel lymph node when the Breslow thickness of Clark level increased. It is highly probable that the sample size was insufficient for any statistical significance.

The prognostic value of the Clark level for the presence of positive sentinel lymph node melanoma has been stated in other studies.18,19 Analysis of previously published studies reveals that the cutting off levels of the Clark index used vary greatly, hindering the comparison of results and no optimum Clark level has been established for predicting the presence of positive sentinel lymph nodes.2

In our study we found there was no significant relationship between ulceration and sentinel lymph node involvement, in contrast to other series, in which ulceration is negatively associated with survival in all Breslow melanoma subgroups,21 with the result that it is included in the AJCC's TNM classification from its sixth edition. However, Sondak et al.22 found no association between the presence of ulceration and a positive sentinel lymph node result. They attribute this to the different possible causes of ulceration and to the error which may induce its presence on measuring Breslow tumour thickness.

Age and gender variables were not significant in the univariate analysis; age has been a subject for debate in several studies18,19,22 and several studies detected less lymph node incidence in older patients despite them having a lower disease-and survival-free period.18 Moreover, the relationship between gender and the result of the sentinel lymph node biopsy has not been established, with some studies showing a higher number of positive sentinel lymph nodes in males21,23 and others which did not.18,19,22 In our study females presented with a higher percentage of sentinel lymph nodes but this outcome was not statistically significant.

No statistically significant differences were found for any of the variables analysed in the multivariate analysis. This result could be due to several factors: the sample size, the scarcity of events and also because many histological variables such as Breslow density, Clark levels and ulceration are correlated with one another, which may lead to possible confusion.20

We found 2 cases in which the sentinel lymph node was negative and local lymph node recurrence occurred, giving rise to a false negative rate of 9.5%, that falls within the range observed in other studies of between 4% and 32%.5,12,24 These false negatives may be associated with different factors: the learning curve of the technique,25 the alteration of lymphatic dissemination routes associated with primary tumour removal, lymphatic obstruction due to tumour cell embolism, the presence of a sentinel lymph node in the neck,26 insufficient histopathological analysis and haematogenous dissemination.

Recurrences were more frequent in the patient group with positive sentinel lymph node results (22.7%) than in that of negative sentinel lymph node results (13.63%), although no statistically significant differences were obtained. In our study the rate of local recurrence following lymphadenectomy after a positive sentinel lymph node was 13.6%, a figure in the range of that published in other studies which would vary between 0 and 20%.8,27 However, the rate of local recurrence after a lymphadenectomy of clinically palpable nodes ranged between 20% and 50%.27–29 It is difficult to differentiate whether greater regional control is associated with the lymphadenectomy performed after a positive sentinel lymph node result. Another study27 compared 2 patient groups with positive sentinel lymph nodes retrospectively from different hospitals; a lymphadenectomy had been performed on several of them. The authors did not find any significant differences in terms of survival between both groups. We would highlight that in our study only 2 patients of the 22 with positive sentinel lymph nodes presented other affected lymph nodes (11%) in the lymphadenectomy, and among those who presented with negative lymphadenectomy, another 2 patients (13%) developed local recurrence. These results raised doubts as to the ultimate effectiveness of lymphadenectomy.

With regard to sample mortality, 3 deaths occurred (4.3%) which were directly related to the melanoma during an average follow-up period of 95 months. This percentage is slightly lower than that of other seriess14,15 where mortality is around 8%. This difference could be explained by the high percentage (23.5%) of patients included in our sample who were in the initial stages of the disease. This percentage was also above that of the before-mentioned series where it was around 4%. The sentinel lymph node biopsy result is considered the most specific and sensitive prognostic factor for disease-free and overall survival.20 In our study, however, we found there were no statistically significant differences in terms of mortality between patients with positive and negative sentinel lymph nodes. This may be explained by the low number of recorded incidences.

The frequency of postoperative complications (seroma, infection) observed in our study was similar to that of other studies, in terms of morbidity related to sentinel lymph node analysis,30 with a clear difference noted between the secondary effects associated with the sentinel lymph node biopsy compared with lymphadenectomy, where results were statistically significant.

We have shared our 8 year experience in our hospital with sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma patients and observed that this study was subject to several limitations such as: sample size; scarcity of recorded data associated with the sample's high survival rate and the fact that data collection was retrospective.

ConclusionThe sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma patients offers useful information about the lymphatic dissemination of melanoma and allows an approximation to the regional staging, sparing the secondary effects of lymphadenectomy. However, studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods will be necessary to confirm the validity of sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma patients, and especially of lymphadenectomy in patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Bañuelos-Andrío L, Rodríguez-Caravaca G, López-Estebaranz JL, Rueda-Orgaz JA, Pinedo-Moraleda F. Biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela en melanoma: experiencia durante 8 años en un hospital universitario. Cir Cir. 2015;83:378–385.