This article reports an analysis of the therapeutic alliance in two contrasting couple therapy cases for depression with different outcome in terms of depressive symptoms. The System for Observing Family Therapy Alliances (SOFTA-o) was used to analyze the therapeutic alliance established by all the participants, including clients but also therapists, during the first, sixth and last sessions of the treatment. The alliance is best assessed using micro-process analysis, allowing it to provide valuable information to the therapist on what is happening in treatment when a partner is suffering from depression. A collaborative alliance between both members is necessary in order for the therapist to establish a context of mutual support in which the couple is seen working collaboratively. Finally, there is discussion of the importance that the therapeutic alliance can make in couple therapy for depression, with mention also of the implications for research and for clinical practice.

Este estudio se basa en el análisis comparativo de la alianza terapéutica en dos casos de terapia de pareja para la depresión con distinto resultado terapéutico, en términos de cambio sintomático. El Sistema para la Observación de la Alianza Terapéutica en Intervención Familiar (SOFTA-o) se utilizó para evaluar cómo la pareja establecía la alianza terapéutica con el terapeuta y, por el otro, como el terapeuta construyó la alianza terapéutica con la pareja en el proceso de terapia, durante la primera, sexta y última sesión del tratamiento. Se valoró la construcción de la alianza terapéutica mediante un análisis de micro proceso para proporcionar una información más exhaustiva sobre el transcurso de la terapia. Se considera de gran relevancia que el terapeuta fomente la creación de un contexto de soporte mutuo entre la pareja para que ésta trabaje en la terapia de un modo colaborativo. Finalmente, se discute sobre la importancia de la alianza terapéutica en terapia de pareja para la depresión, con una mención a las implicaciones que tiene este estudio en la investigación y en la práctica clínica.

Many researchers have established the centrality of the therapeutic alliance as a necessary condition for the undertaking of therapy, often attributing to it a role of facilitating the therapeutic effect (Blow, Sprenkle, & Davis, 2007; Bordin, 1979; Horvath, Del Re, Fluckiger, & Symonds, 2011). Research over the last two decades has accumulated evidence about the therapeutic alliance as a necessary condition for the effectiveness of therapy (Blow et al., 2007; Escudero, Heatherington, & Friedlander, 2010; Horvath et al., 2011). Some of these scholars have examined the therapeutic alliance and its relationship with treatment outcomes. Researchers have examined how this alliance acts in diverse forms of therapy, such as individual therapy (Martin, Garske & Davis, 2000), family therapy (Bolle, Johnson, & De Fruyt, 2010) and couple therapy (Anderson & Johnson, 2010; Brown & O’Leary, 2000; Knobloch-Fedders, Pinsof, & Mann, 2007; Mateu, Vilaregut, Campo, Artigas, & Escudero, 2014).

A key question that has arisen in research is the direction of the relationship between the therapeutic alliance and therapeutic outcome. The significant correlation between alliance and outcome could suggest one or more different processes: (a) a strong alliance causes a symptomatic change; (b) a symptomatic change positively influences the perception of the alliance; or (c) the two variables exert a mutual influence on one another (Barber, Connolly, Crist-Christoph, Gladis, & Siqueland, 2000). In order to show a causal relationship between the therapeutic alliance and symptomatic change, it is necessary to demonstrate that the improvement in symptoms persists after the evaluation of the alliance, so as to control for possible reverse causality (Falkenström, Granström, & Holmqvist, 2013).

With these considerations in mind, former research suggested that there exists a connection between the therapeutic alliance and consequent symptomatic change, on condition that the symptomatic change is controlled for prior to the assessment of the alliance (De Bolle et al., 2010). The alliance and the symptomatic change mutually influence each other during the therapeutic process (Falkenström et al., 2013; Heene, Buysse, & Van Oost, 2005). As Tasca and Lampard (2012) have stated, a patient that experiences a worsening of his or her symptoms during treatment might start to doubt the efficacy of that treatment, thereby weakening the therapeutic alliance, and vice versa.

Taking into account this consideration, the purpose of this study is to compare the differences in the therapists’ contributions and the clients’ responses regarding to the therapeutic alliance in two cases of couple therapy, each with a different therapeutic outcome in terms of depressive symptoms. An intensive analysis of the therapeutic alliance including all the participants in the third, sixth and last sessions were done for two contrasting cases with different outcome regarding the improvement of the depressive symptomatology at the end of the therapy.

An examination of the latest alliance literature in the broader context of psychotherapy research brings to light an emphasis on the importance of exploring early session alliance formation (Knobloch-Fedders et al., 2007) and the maintenance of the alliance during the course of therapy (Owen, Reese, Quirk, & Rodolfa, 2013). More precisely, positive associations have been found between alliance-related behaviors in family therapy and symptomatic change both early and later in therapy, but little is known about this connection in the couple therapy setting.

These reflections led us to speculate about the quality of the therapeutic alliance in couple therapy and its role as a facilitator of the symptomatic change achieved at the end of therapy. The act of incorporating two or more members into the psychotherapeutic process might complicate this relationship between alliance and therapeutic result. In such a context, the alliance is a fluctuating process, and the therapist must establish and maintain several alliances at the same time during the session (Anderson & Johnson, 2010; Pinsof & Wynne, 2000; Rait, 2000).

For this reason, a complete picture of the alliance requires an accounting of how well the family works together in therapy, as well as a look at how similarly individuals feel about the therapist. When alliances are “split” or “unbalanced” (Pinsof & Catherall, 1986) at least one family member has a stronger bond with the therapist than other family members. In couple and family therapy, these split alliances occur frequently and vary in severity (Mamodhoussen, Wright, Tremblay, & Poitras-Wright, 2005).

Achieving an alliance in family and couple therapy, just as in individual therapy, involves negotiating goals, tasks, and bonds. However, we would point to two systemic features of the alliance which are specific in conjoint therapy: the degree to which clients feel safe in a therapeutic context with other family members, as well as collaborate effectively with each other during sessions (Friedlander et al., 2006).

According to these findings, Friedlander, Escudero, and Heatherington (2009) pointed out that members of a couple don’t always value therapy in the same way. To do effective work with couples, the therapist has to pay attention to the needs of both members of the couple, connecting them so that they make sense to the system. This strategy consists of highlighting common values and creating a safe therapeutic context (Escudero, Friedlander, Varela, & Abascal, 2008). A couple with low levels of communication and conjugal trust is able to come to fewer agreements in therapy; therefore, in these cases establishing an alliance within the couple's system is key to therapeutic improvement (Johnson, Ketring, Rohacs, & Brewer, 2006; Mateu et al., 2014).

Friedlander, Escudero, Heatherington, and Diamond (2011) carried out a meta-analysis of the relationship between the therapeutic alliance and the outcome in couple and family therapy. This meta-analysis was made up of 24 studies with a total of 1461 clients, and it found a significant relationship with a small effect size of .26 (p<.001). Therefore, previous studies regarding the relationship between therapeutic alliance and outcome in couple and family therapy show a very similar results to that found in studies on individual psychotherapy (Anderson & Johnson, 2010; Escudero, 2009; Horvath et al., 2011; Knobloch-Fedders et al., 2007).

With regard to the characteristics of the therapeutic alliance in couple therapy, we hope to provide more information about how the therapeutic alliance is constructed in a clinical setting when one of the individuals has been diagnosed with a severe mental disorder, in particular Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Researchers have come to relatively few conclusions as to how the alliance is associated with symptomatic change during the course of treatment in a couple with clinical symptomatology. Because there have been few studies aimed at shedding light on the relationship between the buildings of the therapeutic alliance in couple therapy on the one hand and the treatment of MDD on the other, we believe it is important to assess how the relational dynamics of the couple could influence on the quality of the therapeutic alliance, and consequently, how it effects changes in symptoms.

Some studies have been conducted with regard to the connections between the therapeutic alliance and depression in individual therapy (Arnow et al., 2013). However, the field of couple therapy has to date paid scant attention to these two variables.

Thus, our intention is to use case studies to expand the base of dynamic, micro analytical knowledge on the process of building the therapeutic alliance. Recent research in this area has suggested the need for further studies geared toward an examination of how this alliance is created (Hatcher & Barends, 2006). These suggestions have taken the shape of calls by researchers for studies to analyze the “small-scale interpersonal events” that occur in therapy in order to understand and describe the dynamics that are present in certain contexts and to verify or generate theory (Horvath et al., 2011).

Research has established a strong relationship between marital discord and the severity and course of depression (Artigas, Mateu, Vilaregut, Feixas, & Escudero, 2017; Goldfarb, Trudel, Boyer, & Préville, 2007; Heene et al., 2005). Additionally, some studies have established that the quality of a patient's past and current relations influences on the development of the therapeutic alliance; for that reason, it is beneficial to take into consideration past and present relational experiences in therapies treating depressive disorders, since they affect both the patient's symptoms and the construction of the therapeutic alliance (Crits-Christoph, Gibbons, & Hearon, 2006; Feixas, Muñoz, Dada, Compañ, & Arroyo, 2009; Linares & Campo, 2000).

Past studies have shown that including partners in the treatment process can be effective when treating patients with depression. Whisman, Johnson, Be, and Li (2012) recently reviewed the current research on couples therapy interventions when one partner is suffering from depression. According to the findings of these authors, even when couples are not feeling marital conflicts, the long-term recovery is intermediated by an interpersonal process, as is the decrease of blame and anger to the partner (Barbato & D’Avanzo, 2008).

Along the same lines, Kuhlman, Tolvanen, and Seikkula (2013) conducted a study that highlights the essential task of the spouse's contribution in treatment for depression. These researchers argued for the need to take into account the connection between subjective distress and the alliance during the treatment, and for the discussion of individual well-being and relational issues, in addition to the focus on depression. For this reason, if insufficient attention is paid to the couple's joint necessities, both the patient and spouse may have the inadequate sensation they are not being sufficiently heard (Goldfarb et al., 2007; Kuhlman et al., 2013; Rautiainen & Aaltonen, 2010).

Researchers have taken an interest in the treatment of couples as a form of alleviating depression, supposedly by changing the patterns of dysfunctional relationships. The systemic model provides a framework specifically designed to address relationship patterns in treating couples. Leff et al. (2000) evaluated the effectiveness of Systemic Couple Therapy for Depression. One of the main findings was that SCT was shown to be more effective and better received than anti-depressant medication.

Based on the above, we undertook this study with the dual objectives of (1) comparing the differences in the construction of the therapeutic alliance in two cases of couple therapy, each with a different outcome in terms of depressive symptoms; and (2) analysing the ways in which therapists contribute to the construction of the therapeutic alliance and influence the therapeutic outcome.

MethodTreatmentThe intervention model was based on the Jones and Asen (2000) treatment protocol for Systemic Couple Therapy (SCT) for Depression. The SCT was used in the Leff et al. (2000) clinical trial, which was published as a therapy manual, and thus became available for treatment and research purposes. The key assumption of SCT is that patient's depressive symptoms are primarily maintained by the current relationships in which he or she participates (couple, family, social contacts, health care system, etc.). So, the focus of SCT work is on addressing the depressed person's difficulties in their relational context. Consistent with its focus on communication processes, SCT conceptualizes depression as an interpersonal event. From this point of view, the depressive state of the patient affects the partner and the partner's responses affect the patient's depression; hence, a central issue is to identify and modify circular processes of symptomatic behavioral reinforcement. According to this systemic approach, SCT conceptualizes alliance formation as a continuous process and thus requires a session-by-session assessment. Once the partners have agreed to undergo couple therapy, they must assert their informed consent.

The treatment was split into two stages, with a planned duration of anywhere between 12 and 18 sessions. The first stage consisted of consultation and evaluation and took up the first three sessions of the therapeutic process. The first session explored the couples’ complaints and their principal areas of conflict, and the procedure of the therapy was outlined in detail by the therapist. In the second session the therapist undertook an exhaustive investigation into the couple's families of origin. In the third session both members of the couple told their version of the history of their relationship. In these three sessions, the principal objective was to lend the patient's symptomatic behavior significance through its connection to the dysfunctional characteristics of the context that had fueled its continuation. In the second stage, in which the therapeutic contract already existed, the therapist worked with the couple to consolidate a context in which positive interactions and more functional communication predominated, along with the learning of new methods of conflict resolution through therapeutic prescriptions.

ParticipantsSelection of casesThe two cases chosen for the study were recruited in Spain, within the University Barcelona research project on couple therapy for depression, and the treatment was based on the Jones and Asen (2000) treatment protocol for Systemic Couple Therapy (SCT; Leff et al., 2000) and administered at a Public Health Center.

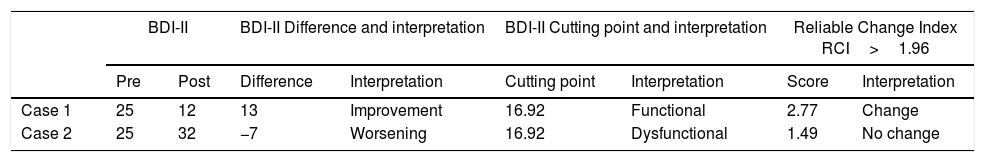

As has been extensively described in our former work, in both cases, the female participant was diagnosed with a long-term Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), according to DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) criteria. The post therapy scores of the patient in Case 1 showed a non-clinical status (BDI-II<16.92), and The Reliable Change Index (RCI; see Procedure section below) indicated a clinically significant change throughout the therapy progress (RCI>1.96). The patient in Case 2 presented a symptomatic deteriorating at the end of therapy, therefore, the change was not clinically significant. Additionally, both couples agreed to the termination of the therapy with the therapist. Thus, two different criteria were taken into account in the selection of cases. On the one hand, both patients showed the same severity of depressive symptoms at the beginning of therapy, and on the other hand, both patients presented significant dissimilarities regarding the symptomatic change at the end of the therapeutic process (see Table 1).

Evolution of scores and reliable change index for depressive symptom severity (BDI-II).

| BDI-II | BDI-II Difference and interpretation | BDI-II Cutting point and interpretation | Reliable Change Index RCI>1.96 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Difference | Interpretation | Cutting point | Interpretation | Score | Interpretation | |

| Case 1 | 25 | 12 | 13 | Improvement | 16.92 | Functional | 2.77 | Change |

| Case 2 | 25 | 32 | −7 | Worsening | 16.92 | Dysfunctional | 1.49 | No change |

Case 1. Both members of the couple were 60 years old, and at the time of consultation, they had been married for 28 years. The couple decided to start couple therapy due to the strengthening of the depressive symptomatology of the patient. The patient complained of a 20-year period of depressive symptoms without remission: emotional discomfort, apathy and distress. Particularly, she had been receiving psychopharmacological treatment for the past 8 years. The symptoms she referred to were related to family of origin concerns.

Regarding the couple's married life, conflicts existed around the difficulties they experienced in harmonising their communication styles and in the resolution of conflicts linked to the patient's problems with her family of origin.

Case 2. The average age of both partners were 62 and they had been married for 34 years. The couple agreed to start therapy due to the intensification of the depressive symptomatology in the patient as well as an increase in their marital conflicts.

The patient had undergone psychiatric treatment for her depressive symptomatology since she was 28 years old. Her mother died when she was eleven months old and, being the youngest of her siblings, she had to take on a series of responsibilities within the family structure at a young age.

Concerning their conjugal relationship, the couple had difficulties in terms of communication and problem solving, and they presented discrepancies about what it meant to be a couple. It was brought out that the non-depressed partner is the one who assumes an ‘up’ position, and the depressed patient assumed a ‘down’ position due to the depressive symptoms. A complementarily rigid interactional pattern of depression, in which there were uneven power roles, was found out.

Therapists. The therapeutic team was consisted of two co-therapists and a supervisor. Although the co-therapists were different in the two selected cases, in both of them the primary therapist was a male family therapist with four years of clinical training and he played the most active role in the co-therapy process. The second therapist was a novice female therapist. Moreover, in both cases the supervisor was a PhD holder and clinical psychologist who had over 20 years of experience in systemic therapy. Supervision sessions took place in between each therapy session and featured the viewing of videotapes to guarantee therapists’ adherence to the manual.

InstrumentsThe System for Observing Family Therapy Alliances (SOFTA-o) (Escudero & Friedlander, 2003) is an observational tool for assessing the construction of the therapeutic alliance. It is considered to be applied by external evaluators while viewing a recorded session of conjoint therapy, and it has a dual function. On the one hand, it evaluates how the couple or family establishes the therapeutic alliance with the therapist; on the other, it evaluates how the therapist contributes to the therapeutic alliance with the clients over the course of therapy.

In this observational rating system, trained observers evaluate a session, perceiving the frequency of particular positive and negative alliance-related indicators that are assembled in four dimensions: Engagement in the Therapeutic Process, Emotional Connection with the Therapist, Safety Within the Therapeutic System, and Shared Sense of Purpose Within the Couple. The SOFTA-o is composed of 44 observable behaviors or indicators for the members of the family or couple, (negative and positive) grouped in the four dimensions and of 43 observable behaviors or indicators corresponding to the contributions (negative and positive) of the therapist to the therapeutic alliance in each of the SOFTA-o dimensions.

The authors conceived the Engagement in the Therapeutic Process as an inter-system factor that reflects the two components of the conceptualization of Bordin's (1979, 1994) alliance between the patient and the therapist about the goals and tasks in therapy. This dimension underscores the importance of patients feeling like protagonists in the definition of their problems. The degree to which a family member or partner considers work to have meaning depends on the vision of the other members. Some examples of Engagement indicators performed by the patient and that are considered as a positive are: “The patient indicates agreement with the therapist's goals” or “The patient introduces a problem for discussion or the patient expresses optimism or indicates that a positive change has taken place”. On the other hand, as an example of negative indicators of the Engagement dimension would be consider: “The patient expresses feeling ‘stuck’ questions the value of therapy, or states that therapy is not or has not been helpful” or “The patient shows indifference about the tasks or process of therapy (e.g., paying lip service, “I don’t know,” “tuning out)”. And some examples of positive therapist's contributions to engagement are: “Therapist explains how therapy works” or “The therapist asks patient(s) whether they are willing to follow a specific suggestion or do a specific homework assignment”. On the contrary, indicators of the therapist that can contribute negatively to the Engagement are: “Therapist defines therapeutic goals or imposes tasks or procedures without asking the client(s) for their collaboration” or “The therapist shames or criticizes how clients did (or did not do) a prior homework assignment”.

Emotional Connection with the Therapist reflects the conceptualization of the therapeutic alliance of Bordin (1994) with respect to the existence of a positive emotional bond and trust between the patient and the therapist. The affective quality of the relationship between therapist and patient includes that the patient feels understood, supported and valued. Some indicators that indicate a high degree of Emotional Connection with the therapist are: “The patient verbalizes trust in the therapist; patient indicates feeling understood or accepted by the therapist” or “The patient expresses physical affection or caring for the therapist”. Instead, it is considered a lower degree of Emotional Connection if some of these indicators are presented: “The patient has hostile or sarcastic interactions with the therapist” or “The patient comments on the therapist's incompetence or inadequacy”. Some examples of a positive therapist's contribution are: “The therapist expresses caring or touches patient(s) affectionately yet appropriately (e.g., handshake, pat on head)” or “The therapist (verbally or nonverbally) expresses empathy for the patient’ struggle (e.g., “I know this is hard,” “I feel your pain, “crying with patient”. And it is considered that contributes in an unfavorable way to Emotional Connection if these two behaviors are presented: “The therapist has hostile, sarcastic, or critical interactions with the patient(s)” or “The therapist does not respond to clients’ expressions of personal interest or caring for him or her”.

Friedlander et al. (2006) defined the Safety Within the Therapeutic System as follows; “the patient viewing therapy as a place to take risks, be open, vulnerable, flexible; a sense of comfort and an expectation that new experiences and learning will take place, that something good can come from being in therapy, that conflict within the family can be handled without harm, that one need not be defensive” (p. 9). Some examples that the patient feels safety are: “The patient shows vulnerability (e.g., discusses painful feelings, cries)” or “The patient reveals a secret or something that other family members didn’t know”. In contrast, other indicators that indicate a negative Safety would be: “The patient makes hostile or sarcastic comments to family member” or “Family members try to align with the therapist against each other”. And some examples that the therapist contribute in this dimension are: “The therapist attempts to contain, control, or manage overt hostility between clients” or “The therapist changes the topic to something pleasurable or non-anxiety arousing (e.g., small talk about the weather, room decor, TV shows, etc.) when there seems to be tension or anxiety”. On the contrary, negative contributions from the therapist, in this dimension are: “The therapist allows family conflict to escalate to verbal abuse, threats, or intimidation” or “The therapist does not attend to overt expressions of client vulnerability (e.g., crying, defensiveness)”.

Finally, the Shared Sense of Purpose dimension reflects three aspects between the members of the couple or family: (1) the agreement between the members of the family/couple about the goals and tasks of the therapy; (2) its homogeneity and cohesion as a unit; and (3) the value they give to therapy as a way to treat family problems (Friedlander et al., 2006). Some examples that show that the couple or family have a positive Shared Sense of Purpose are: “Family members offer to compromise” or “Family members validate each other's perspective”. Contrarily, other indicators that show a sense of sharing the negative purpose would be: “Family members blame each other” or “Family members try to align with the therapist against each other”. Finally, some examples regarding positive contributions, in the dimension by the therapist are: “Therapist encourages clients to compromise with each other” or “The therapist encourages clients to show caring, concern, or support for each other”. On the other hand, negative contributions from the therapist in this dimension are: “Therapist fails to intervene when family members argue with each other about the goals, value, or need for therapy” or “Therapist fails to address one client's stated concerns by only discussing another client's concerns”.

After observing at the session and taking into deliberation the valence (positive or negative), frequency, intensity, and clinical relevance of the observed indicators, evaluators provide overall ratings from −3 (extremely problematic) to +3 (extremely strong) on each dimension. Each partner receives a separate score on Engagement, Emotional Connection and Safety, and the couple as a unit obtains a joint punctuation on Shared Sense of Purpose.

In the current study, the external evaluators rated the sessions independently following the SOFTA-o rating guidelines (Friedlander et al., 2006) and, subsequently, the final scores were based on consensus rating for the clients and therapists SOFTA versions. Reliability tests carried out on both the English and Spanish versions of SOFTA-o reported intra-class correlations of between .72 and .95 for each of the four dimensions that make up the instrument (Friedlander et al., 2006).

The Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996; Spanish adaptation by Sanz & Vázquez, 2011) was administered in order to assess the depressive symptoms of the patients. It is a questionnaire composed of 21 multiple-choice items to be completed by the patient, which measures the severity of depression and has a high reliability coefficient (α=.89). It was administered at the pre and post treatment to evaluate symptomatic change. Sanz and Vázquez (2011) determined 16.92 as the cut-off point for the Spanish population.

ProcedureThe procedure carried out in the current research was established within the framework of the above-mentioned project on couple therapy for depression and it has been well described in a previous study in which the connection between therapeutic alliance in clients and their dyadic adjustment is considered (Artigas et al., 2017). However, some methodological particularities in the present study, concerning the variables and the participants included in the analysis stated here, must be taken into account. The rating task was carried out by three observers, who analyzed all the data included in the present study. It is worth mentioning that the observers were the first three authors of this article. The final rating, which was used for the purposes of data analysis, was based on consensus rating between the three evaluators.

In order to adequately verify inter-observer reliability, a team of three SOFTA-o trained observers evaluated the therapy sessions (Friedlander et al., 2006). To calculate the reliability between observers, the analyzed sessions were evaluated and average intra-class correlations of .81 for the Engagement dimension, .97 for Emotional Connection, .97 for Safety, and .97 for Shared Sense of Purpose were reported. The observers received training in the use of the instrument both during an academic residency with its designer, Dr. Valentin Escudero (A Coruña University, Spain) and through subsequent sessions involving 20h of analysis of cases distinct from those included in the study.

The Spanish version of SOFTA-o (Sistema para la Observación de la Alianza Terapéutica en Intervención Familiar, SOATIF; Escudero & Friedlander, 2003) was used to analyze the first, sixth and final therapy sessions. The sessions were filmed and then observed, and later they were transcribed verbatim to make possible a more in-depth analysis of the therapeutic alliance for both clients’ and therapist’ versions.

Before therapy, the participants started a three-session assessment phase in which two independent and especially trained Master's students administered the instruments in face-to-face interviews. In these sessions, as well as in all the following therapy sessions, both partners answered the BDI-II on arrival. Note that the non-depressed partners were also asked to complete the BDI-II, but according to their perspective of the patients’ state. In this way, the researchers obtained the assessment of patient's depressive symptoms from her own point of view as well as that of her partner. Once the assessment process was made, both couples started the therapy, which lasted 17–18 fortnightly sessions, according to the time-limited treatment protocol for Systemic Couple Therapy (SCT; Leff et al., 2000). The couples and therapists agreed to end the therapy process, and in that moment there were three outcome-assessment sessions in which the couples also were asked to respond the aforementioned BDI-II.

To consider clinically significant change, we used the criteria suggested by Jacobson and Truax (1991). These authors suggested the Reliable Change Index (RCI), which is calculated by dividing the change in a patient's scores at the start and the end of therapy by the standard error of the test being used. In other words, the RCI addresses whether the change detected is of enough magnitude to guarantee that it goes beyond possible measurement error. If the index exceeds 1.96, the change in scores as a result of treatment is considered statistically significant (95% confidence interval). The Spanish normative data (Sanz & Vázquez, 2011) was used in relation to the BDI-II in order to estimate the cut-off and RCI values. An RCI was computed for each BDI-II score after the end of the therapeutic process (dysfunctional population: mean 27.31, SD 11.04; functional population: mean 9.61, SD 7.61; test–retest reliability 0.91).

ResultsRegarding the severity of the symptoms, the scores recorded at the start of the psychotherapeutic process using the BDI-II indicated a status of dysfunctionality in both cases. Nevertheless, the post-treatment scores of the patient identified in Case 1 indicated a non-clinical status (BDI-II<16.92), and The Reliable Change Index (RCI) showed a clinically significant change (RCI>1.96). However, the patient identified in Case 2 experienced a worsening of her symptomatology post-treatment, and the change was not clinically significant.

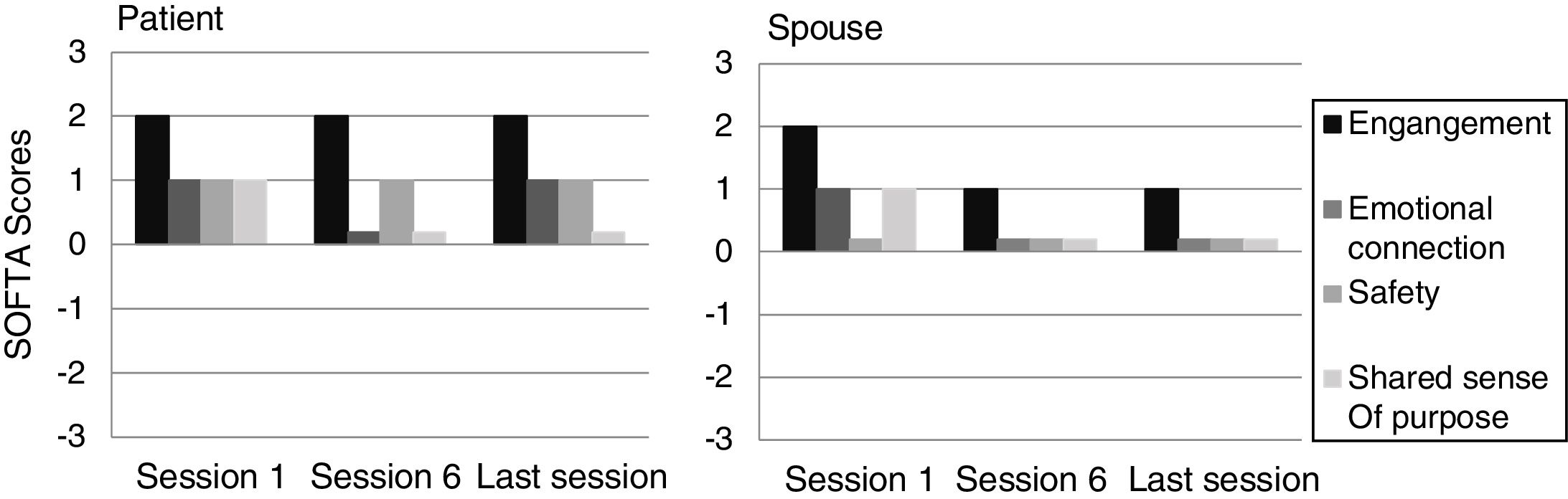

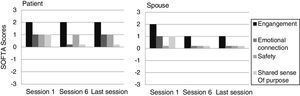

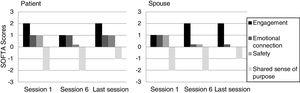

We conducted an analysis with SOFTA-o, both the clients’ and therapist's versions, of the first, sixth and final sessions. We examined the evolution of the therapeutic alliance over the course of the therapeutic process in the two cases. In Case 1, the alliance scores for both members of the couple were fairly stable, and were always positive toward the therapy. If we compare the scores from the three sessions analyzed, an adequate therapeutic relationship was created in the first session, and a lower score was obtained in the sixth session. The sixth session was devoted to treating the issues arising from Nicole's conflict with her sister, which followed the death of their parents. The greatest divergences between the couple's scores were produced in the Safety dimension: Nicole perceived the therapeutic context as safe enough for her to be able to open up emotionally in the sessions, and thus was generally given scores de +1 for this variable in each session. Meanwhile, George didn’t display as many indicators of this dimension, and although he received scores of +1 or 0 for the sessions, he displayed the indicators of Safety much less often. The couple obtained joint positive scores in the Shared Sense of Purpose dimension, with marks of +1 in the second and the final session, and of +2 (representing a quite strong alliance) for the sixth session (see Fig. 1).

In Case 2, the couple's alliance scores were more variable throughout the process than in Case 1. It is worth noting that Mary obtained higher scores than Robert. If we compare the three evaluations made, the most positive scores in the establishment of the therapeutic alliance were made in the final session. Conversely, the sixth session was the most difficult one for the couple. This session was focused on treating their areas of conflict, for example the problems relating to Robert's family of origin, and this stirred up resentment and prompted blaming between the spouses. In all the sessions analyzed, the most positive and consistent dimension was Engagement. To be precise, the patient got scores of +2 in the first and final sessions, and she was given a mark of +1 for the sixth session. Her spouse also scored well for this variable, with a rating of +1 for the first session and +2 for both the sixth and the final sessions. The Emotional Connection dimension displayed moderately positive scores, and the greatest differences between the members of the couple were apparent in this area. The patient was given a low but positive score for all the sessions, but her spouse recorded scores of 0 (neutral or not noteworthy) throughout the process. In comparison with Robert, Mary showed more indicators of feeling understood and accepted by the therapist. The result implies that Mary had a stronger bond with the therapist than Robert, and this may be an indicator of a “split alliance” (Mamodhoussen et al., 2005).

The couple also achieved moderately positive scores in the Safety dimension. The patient scored a +1 for both the first and last sessions, while her spouse was given neutral marks or deemed unscorable for all the sessions. Without a doubt, the most problematic scores were produced in the Shared Sense of Purpose dimension. Throughout the session there were indicators that showed the couple's difficulty to work as a team and thereby jointly improve their relationship (see Fig. 2).

The most notable difference between the two cases is found in the Shared Sense of Purpose dimension. In Case 1, the scores were positive or neutral, showing that the couple were capable of working as a unit to make a change. In contrast, in Case 2 the scores were very negative. The scores for the first and last sessions were in the “slightly problematic” range, while the raters indicated that the sixth session fell into the “quite problematic” category (−2), evincing the high level of conflict that shaped the couple's relationship, and the lack of commitment to working together to find solutions to the problem.

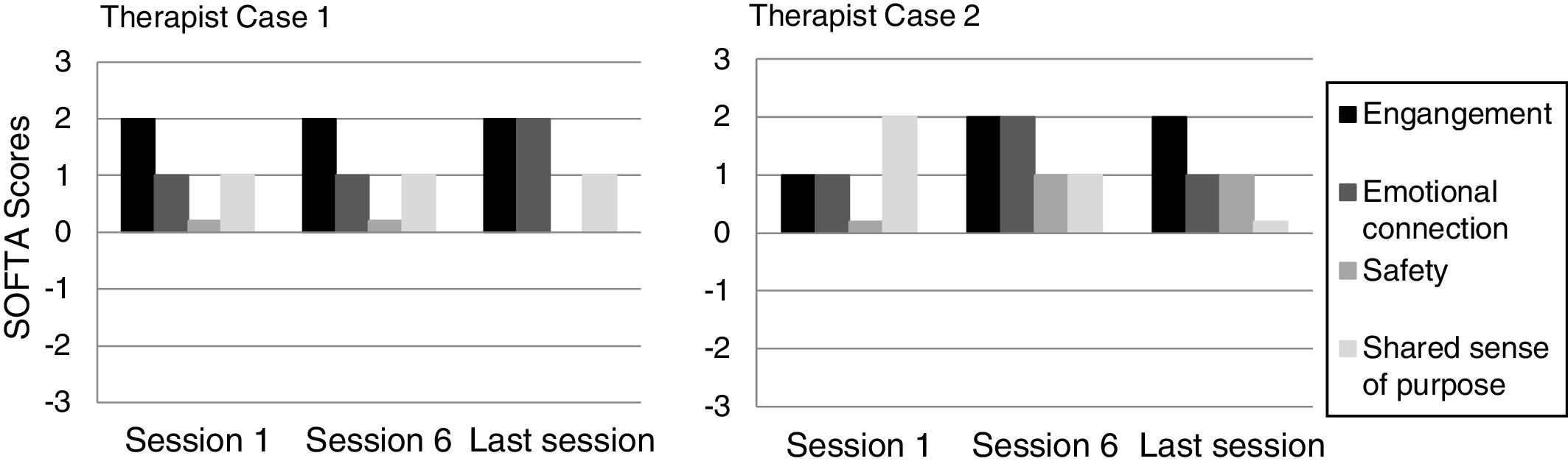

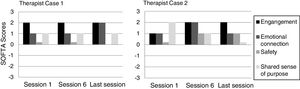

We analyzed the evolution of the therapeutic alliance that the therapists experienced in each of the two cases. On the one hand, both therapists obtained neutral or positive scores throughout the therapeutic process, and Engagement was the most positive dimension. On the other hand, the scores for the therapist in Case 2 fluctuated more than those for the therapist in Case 1, whose scores remained more stable. In Case 1 in particular, the therapist obtained higher scores for the Engagement dimension, specifically a score of +1 (slightly positive) for all the sessions, and this therapist was also given fairly positive ratings for the Emotional Connection dimension. The therapist's performance is apparent in the exchange below, for which scores for each of the dimensions were given: “Therapist: Yes, yes, I think you’re both perfectly within your rights. You (talking to George) worry, reasonably, because it's been a long time and the situation is fragile, and that's understandable. And in your case (talking to Nicole), it's what we’ve discussed. Of course sometimes you might feel anxious, you might feel you’re being controlled (Nicole nods), and this means your life isn’t as pleasant as it could be, right? But of course you keep doing what you usually do, because it's part of your identity. But the positive thing about this whole process is learning how to gradually adapt better and better (George nods). What happened last week was the start, and now it's starting to be a routine. And I don’t know, you’re in this process… Nicole: Yes, yes…, I feel I’m in a process of change and that therapy is helping me through the pain I feel” (Final session/00:28:06).

The dimensions with the lowest scores were Safety and Shared Sense of Purpose, because there was not a great deal of conflict between the spouses. In contrast, in Case 2, the therapist focussed more attention on the Safety dimension, which the raters scored +1, or slightly positive. The therapist likely paid extra attention to this area in order to handle the conflict that arose between the members of the couple and minimize the damage from it. This yielded uneven results, as is apparent in the fragment below, in which the therapist tries to contain the hostility between the members of the couple: “Mary: I guess maybe I’m selfish. At least I want him to recognise me and what I have been through. He has seen that I’ve gone through a lot with him, and I want him to recognise how much I’ve suffered with him. And he's never defended me. Therapist: Robert, Do you understand what Mary has been through? Robert: Of course I do. Therapist: Do you admit that she has often suffered in this relationship because of you? Robert: Yes, but it always has to be the same old song with her. Mary: But, what do you mean, “always”? Therapist: You admit it. Robert: I admit it. Therapist: Maybe we can leave it here, Mary. Robert: I admit it. Therapist: Do you admit that you’ve made mistakes? Robert: I’ve made mistakes with her. Therapist: Do you admit that you haven’t defended her? Mary: He has never defended me” (Final session, 00:16:25).

In Case 2, the therapist scored highest in the final session, while in the first and sixth sessions the scores were more moderate. Overall, the Case 2 therapist scored highest in the dimensions of Engagement and Emotional Connection. While the Case 2 therapist got Engagement scores of +2 (representing a quite strong alliance), the same therapist was given neutral Connection ratings for the first session, although these scores increased to +2 and +1 in the sixth and the final sessions, respectively.

This therapist got the lowest score in the category of Shared Sense of Purpose, for which the numbers fluctuated throughout the therapeutic process, reducing the therapist's overall scores. For example, the therapist was rated +1 for the first and sixth sessions, and was given a neutral score for the last one (see Fig. 3).

DiscussionIn this study, we have been able to compare the differences in the construction of the therapeutic alliance in two contrasting cases of couple therapy, and to examine what Barber et al. (2000) considered as an essential inquiry for current research: the link between the alliance and the outcome. The results allow us to state, as previous research has suggested, that it is brought out an association between the therapeutic alliance and subsequent symptomatic change in couple therapy, on condition that the symptomatic change is evaluated earlier to the assessment of the alliance (De Bolle et al., 2010; Tasca & Lampard, 2012).

Currently, there exists wide-ranging research indicating a consistent pattern of strong association between conjugal conflicts and the strength and progress of depression (Goldfarb et al., 2007). The current study provides exclusive findings on the construction of the therapeutic alliance in systemic couples therapies taking into account the multiple members who participate in the therapy sessions. For this reason, the study is offering an in-depth understanding regarding the therapists’ contributions as well as the clients’ responses on the alliance throughout the therapeutic process, as former research has pointed out (Crits-Christoph et al., 2006; Feixas et al., 2009). The current study has been a starting point for subsequent studies exploring the influence of the dyadic adjustment on the patient's symptomatology and the development of the therapeutic alliance in couple therapies when one partner is suffering from depression (Artigas et al., 2017).

Accordingly with various authors, the alliance is identified as a fluctuating process, as just the necessity to evaluate it through the therapeutic process (Falkenström et al., 2013; Tasca & Lampard, 2012). As a result, therapists must pay attention to the patients’ symptomatic worsening at a precise point of the therapeutic process as a possible indicator on a problematic therapeutic alliance in the same session (Pinsof & Wynne, 2000). As a clinical implication, it is well established that the symptomatic level of the patient could provide significant knowledge about how the alliance is progressing during the treatment.

Through the analysis of the therapists’ contributions to the therapeutic alliance, the present study is highlighting the necessity for therapists to balance the relationship with both members of the couple separately as well as to promote the collaborative relationship between the partners in the therapeutic process. As a result of the association between conjugal conflicts and therapeutic alliance during the treatment which was found out by Symonds and Horvath (2004) the current study has clinical significance for therapists and advances our understanding about the most effective therapeutic contributions in order to promote the alliance when working with couples when one member is diagnosed with depression. Additionally, this study has clinical interest since it allows us to detect the most related dimensions of the therapeutic alliance with the symptomatic enhancement and, as a result, with the outcome in couple therapy for depression.

As Anderson and Johnson (2010) showed, the construction of the therapeutic alliance is an especially complicated task in cases where the depression concurs with the conjugal conflicts. Therapists must promote individual therapeutic alliances with each member as well as the alliance established among the couple (Artigas et al., 2017). As we have detected in Case 2, in contrast with Case 1, the members of the couple focused their interventions on resentment and berate from the first session, and thus complicating the therapists’ task of reaching agreements in therapy and promoting a collaborative alliance between both partners in reference to the therapeutic process. Promoting the within-system alliance is essential for the couple to develop a mutual support context and to perceive themselves as a team working to improve their situation. The creation of a sense of unity, in regards to therapy, is a necessary goal in order to achieve satisfactory results, especially in those cases in which depression is related to the conjugal conflicts (Johnson et al., 2006; Pinsof, 1994).

Regarding the reciprocal influence between conjugal conflicts and depression, we consider that the two variables might exert significant influences upon one another. The conflicts uttered by the clients in Case 2 led to the occurrence of numerous indicators of a negative alliance, for instance devaluating each other's opinions or perspective or trying to align with the therapist against each other (Goldfarb et al., 2007; Heene et al., 2005). Accordingly, we believe that conjugal conflicts between the partners are related to the therapists’ difficulties in promoting the within-system alliance, that is, the developing of a mutual support context between them in order to improve conjointly their situation (Crits-Christoph et al., 2006; Feixas et al., 2009; Mateu et al., 2014; Linares & Campo, 2000).

The current study found that the most notable differences between both cases were in the Safety and Shared Sense of Purpose dimensions. According with previous studies in the couple and family therapy field, these two dimensions have been the most discriminative for the prognosis and viability of couple therapy for depression (Friedlander et al., 2009). On the one hand, we would say that the assurance of a feeling of safety within the therapeutic setting is a crucial feature of couple therapy (Friedlander et al., 2009; Goldfarb et al., 2007; Heene et al., 2005). An effort to create such a setting was apparent in Case 2, when due to the resentment and hostility between the clients, the therapist required contributing with more interventions promoting a safe therapeutic setting. In contrast, the satisfactory relationship in the Case 1 required the therapist to make fewer interventions in order to generate a comfortable therapeutic context.

On the other hand, the within-system alliance, assessed through the Shared Sense of Purpose dimension, has revealed the greatest differences in both observed cases. In that sense, it is necessary for the therapist to carry out interventions to facilitate a context of mutual support in which the couple are aware to work as a unit and allows them to bring about new understandings about depression. The therapist's fostering of a sense of unity within the couple in relation to the therapy is necessary to achieve positive outcome, especially in those cases where a high level of marital conflict exists (Friedlander et al., 2009; Mateu et al., 2014).

In reference to the therapists’ analysis, the observers gave them positive scores for all dimensions. Therefore, we can say that the practitioners sought to contributes to generate resources for a positive alliance in both cases. Nevertheless, we highlight the relevance of focusing therapeutic strategies on the creation of an alliance within the couple's system, so that they can work collaboratively. This particularly affects to Case 2, where, given the hostility between the partners caused by their conjugal conflicts, it would have been necessary for the therapist to develop wider range of interventions to implicate the non-depressed partner in the therapeutic process, acquiring a relational comprehension of its situation (Escudero, 2009; Friedlander et al., 2009). As previous research has highlighted, a basic task in couple therapy for depression is based on the creation of a stronger sense of active agency in both spouses, and not only the depressed partner, both in an individual and conjoint level (Artigas et al., 2017; Kuhlman et al., 2013; Rautiainen & Aaltonen, 2010).

We should acknowledge some limitations of the present study. First of all, the observations made have provided us with relevant information to aid the understanding of how the therapeutic alliance was contributed by the therapists and it was established by the clients in two contrasting cases of couple therapy, each with the same level of symptom severity at the pre-treatment, but with different outcomes in terms of symptomatology. At this point, potential case selection bias should be considered, as the authors of the current study also selected the two cases for the sample. Although the selection criterion called for the examination of cases with differing outcome, the possible influence of dyadic adjustment in the evolution of the therapeutic alliance and its association with outcome should be taken into account. Case 1 might have been more successful due to the stronger relationship between the members of the couple and the fact that the woman's distress was due to her extended family, not her husband, while in Case 2 the conflict between the couple was central.

Future studies should address this issue by examining the influence of dyadic adjustment on the alliance and its repercussion in the outcome. Moreover, there were not the same co-therapist team in the two analyzed cases, thus this fact could weak the internal validity of the study. In future studies, we hope to analyze the therapeutic alliance in couple therapy cases with the same co-therapist team. Moreover, it would have been beneficial to make use of other self-report instruments to comprehend the direct perspective of the couple and the therapist through the therapeutic process, and not only at the beginning and the end of therapy. In coming studies, we hope to continue contributing useful strategies for couple therapists established through the dialog that could be effective to develop the therapeutic alliance and to redefine the couples’ interactional patterns, a specially complicated task in cases where the depression concurs with the conjugal conflicts, developing an encouraging line of research that enriches the clinical practice.

The preparation of this article was supported in part by the European Social Fund and the Secretariat for Universities and Research. Ministry Economy and Knowledge (Government of Catalonia, Spain). Grant ref. 2016 FI_B2 00108.