Informal caregiving has a negative impact on the health of caregivers, a role that is mainly played by women. In this context, the objectives of this study were to: (1) assess the physical, mental and overall state of health of female caregivers; (2) study the relationship between their health and caregiving-related burden; and (3) investigate the mediating effect of social support in the relationship between perceived burden related to informal caregiving and the general health of caregivers.

MethodThe sample was composed of 250 women living in the Basque Country (Spain), aged between 30 and 84 years old (M=58.66; SD=10.46). Data were collected on sociodemographic characteristics; the Zarit Burden Interview, SF-12 and Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey were used to measure caregiver burden; quality of life social support respectively.

ResultsOverall, 27.2% of female caregivers reported chronic health problems. There was a link between higher perceived burden and poorer general health in women especially when less social support was available. Further, social support mediated the relationship between perceived burden and general health.

ConclusionsWomen's caregiver burden has a negative impact on their overall health and social support.

El cuidado informal tiene un impacto negativo en la salud de los cuidadores, un papel que desempeñan principalmente las mujeres. En este contexto, los objetivos de este estudio fueron los siguientes: 1) evaluar el estado de salud físico, mental y general de las cuidadoras; 2) estudiar la relación entre su salud y la carga relacionada con el cuidado y 3) investigar el efecto mediador del apoyo social en la relación entre la carga percibida relacionada con el cuidado informal y la salud general de las cuidadoras.

MétodoLa muestra estaba compuesta por 250 mujeres residentes en el País Vasco (España), con edades comprendidas entre los 30 y los 84 años (M=58.66; DT=10.46). Se recopilaron datos sobre las características sociodemográficas; para medir la carga del cuidador se utilizaron la entrevista de Zarit Burden, SF-12 y el cuestionario de apoyo social de Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey.

ResultadosEn general, el 27.2% de las mujeres cuidadoras informaron de problemas de salud crónicos. Había una relación entre una mayor carga percibida y una salud general más deficiente en las mujeres, especialmente cuando se disponía de menos apoyo social. Además, el apoyo social mediaba la relación entre la carga percibida y la salud general.

ConclusionesLa carga de las mujeres cuidadoras tiene un impacto negativo en su salud general y en el apoyo social.

Care arises from the relationship between service and concern for others (Hochschild, 1990). This gives rise, consciously or unconsciously, to attitudes and behaviours that are not performed completely naturally or effortlessly. Nevertheless, this type of care is still being provided through an informal caregiving system, mainly within the family, the associated burden falling on women in most cases (Ruiz-Adame, González-Camacho, Romero-García, & Sánchez-Reyes, 2017). Moreover, this informal care is provided on an unpaid basis, is not visible and lacks social recognition (Masanet & La Parra, 2011).

Despite the psychological impact of providing care in the family setting being widely documented (Liu & Lou, 2017; Schrank et al., 2016), family caregivers have received less attention (Graham, Dempster, McCorry, Donnelly, & Johnston, 2015; Kim, Kashy, Spillers, & Evans, 2010). Caregivers often report loss of friends, changes in daily habits, negative feelings towards the care recipient, giving up work, breakdown in communication with their spouse, and self-neglect, as well as physical symptoms such as headache, tiredness and joint pain. In addition, the following psychological symptoms are common: sadness, low self-esteem, insomnia (Jofré & Mendoza, 2005), depression, anxiety and high levels of stress (Delfino, Komatsu, Komatsu, Neri, & Cachioni, 2018; Kruithof et al., 2016). As well as affecting physical and psychological wellbeing, caregiving has negative effects on financial and employment status and time management (García-Calvente, Mateo-Rodríguez, & Maroto-Navarro, 2004).

In line with this, although women are normally the main informal caregivers, there are also men who assume this role and it should be noted that the burden of care affects men and women differently. Several studies have warned of greater psychological vulnerability and greater attrition in female than male caregivers, indicating that women who are caregivers tend to have more psychological problems (Brazil, Thabane, Foster, & Bédard, 2009; Muñoz, Postigo, Casado, & De Llanos, 2015; Schrank et al., 2016; Swinkels, Broese, de Boer, & Tilburg, 2018; Wadhwa et al., 2013). In addition, Mathias, Kermode, San Sebastian, Davar, and Goicolea (2019) found that women undervalued their role as caregivers and presented negative feelings of hopelessness about their future, while men had a more positive vision of the future and of themselves.

Mendoza et al. (2014) explain the negative impacts of caregiving, most of all on women due to the moral burden they feel linked to being assigned the role of caregiver. In addition, this burden is not recognized socially, which produces contradictory feelings given the difficulty of achieving a satisfactory work-life balance and emotional ambivalence, this leading over time to health problems. In this sense, it is important to recognize that women are the primary caregivers in the family setting even if they do not recognize it themselves (Muñoz & Martín, 2013). In fact, according to Carrasco (2006), care work involves a series of support tasks not only for dependents but also for the vast majority of healthy adult males. All this indicated that the analysis of women as caregivers should not necessarily be limited to those with dependents with chronic illnesses.

Nonetheless, the presence of an individual with a chronic disease and a family caregiver leads to marked changes in the structure and functioning of the family system, creating additional personal tensions in relation to the task of caregiving itself, the associated sense of responsibility and time spent on caregiving (Hernández, 2006). The above produce fatigue in the female caregiver (Ávila, Flórez, Ortiz, Ochoa, & Gallegos, 2012). In this context, it has been found that the poorer the perceived health, especially mental health, the greater the perceived caregiver burden (Fernández de Larrinoa et al., 2011). Stress (Zarit, 2002) maintained over time places burden on the female caregiver which has negative physical health effects and psychological consequences (Carretero, Garcés, Ródenas, & Sanjosé, 2009), such as anxiety, depression, and psychological distress (Pinquart, Sörensen, & Oxington, 2005). Further, it has been found that the number of hours spent caregiving determines or influences the negative effects on mental health (Masanet & La Parra, 2011). A recent study has shown that female caregivers, as well as those who claim that their physical and psychological health is affected, have higher levels of care burden and lower levels of social support (Songül, Züleyha, Ferhan, Nuri, & Özlem, 2016).

Numerous studies have indicated that social support can be effective for improving the wellbeing of family caregivers (Coomber & King, 2012; Del-Pino-Casado, Frías-Osuna, Palomino-Moral, Ruzafa-Martínez, & Ramos-Morcillo, 2018; Perkins & La Martin, 2012). For example, Pinquart et al. (2005) found that higher levels of social support reduce the negative effects of caregiving and are associated with greater life satisfaction, less depression, less caregiver stress (Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya-Albiol, 2012) and lower risk of perceived burden (Aravena & Alvarado, 2010). In line with this, it has been concluded that informal caregivers who report devoting large amounts of time to caregiving and who have few social ties are more likely to experience depressive symptoms (Cannuscio et al., 2004). Hence, level of social support is considered predictive of burden (Kahriman & Zaybak, 2015; Manso, Sánchez, & Cuéllar, 2013). Despite this, paradoxically, although it has been found that female caregivers have greater social support than male caregivers, the negative impact of caregiving on mental health is higher in women (Larrañaga et al., 2008). Notably, although social support is protective against negative impacts on caregivers, when the time devoted to informal caregiving is taken into account, it is seen that social support has a limited role in protecting the mental health of caregivers when many hours are devoted to caregiving (Masanet & La Parra, 2011).

There are few studies of the consequences for the general health of caregiving in female caregivers or of social support as a mediating variable in the relationship between caregiver burden and general health. In a recent study, it was pointed out that although social support may improve the wellbeing of carers, there are not enough studies to conclude whether a change in social support is the underlying mediating factor (Dam, de Vugt, Klinbenberg, Verhey, & Van Boxtel, 2016).

It is important to note that this study, as discussed earlier in the introduction, has been based on the role of caregiver associated with women, regardless of the type of care. In light of all this, the objectives of this study were: first, to carry out a descriptive analysis of the health status (mental, physical and overall) of female caregivers; second, to assess the relationship between health status of female caregivers and caregiver burden; and third, to analyse the mediating effect of social support in the relationship between the perceived informal caregiver burden and general health of female caregivers.

MethodParticipantsThe sample was composed of 250 women living in the Basque Country. The inclusion criteria were to be a woman and have at least a primary level of education to ensure understanding of the questionnaire. Participants’ age ranged between 30 and 84 years, with a mean of 58.66 years and a standard deviation of 10.46 years. The age distribution was as follows: 8.84% of the women were ≤45 years old, 32.53% were 46–55 years old, 31.33% were 56–65 years old, 17.67% were 66 and 75 years old, and 6.02% were >76 years old.

In relation to family size, 40.4% of women in the sample had two children, 21.2% had one child, and 12.4% had three children; the number of children was symmetrically distributed. In relation to the number of people living in the nuclear family, the most common household size was two, 41.2% of the women living in two-person households, followed by 25.2% and 15.2% in three- and four-person households respectively, while 10.4% lived alone. In decreasing order, the women were married (n=155, 62%), single (n=36, 14.4%), widowed (n=24, 9.6%), divorced (n=17, 6.8%); cohabiting (n=9, 3.6%) and separated (n=9, 3.6%). Regarding education, 38% (n=95) of the women had university qualifications, 20.8% (n=52) had technical/vocational training, and 40% (n=16) had completed secondary education while 20.8 (n=52) had just primary education and .4% (n=1) had no formal education. Almost half of the women were formal workers (45.2%), the next most numerous groups being retirees and homemakers (23.6% and 21.6%, respectively). We have assumed that the retired women had worked before retirement and that homemakers had never been employed outside the home.

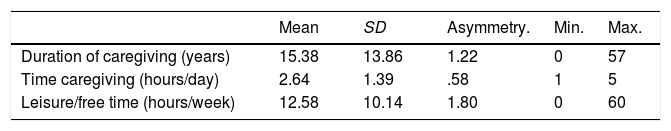

Table 1 shows the results of the descriptive statistical analysis of how long the women had been caregiving, the amount of time they devoted to caregiving and their amount of leisure and free time.

As can be observed, duration of caregiving and time spent caregiving were symmetrically distributed (asymmetry of <1.5). This was not the case for leisure/free time, more women in the sample having few than many hours per week of leisure/free time, with reported times ranging between 0 and 60h and a mean of 12.58h per week. Hence, in this respect, the sample was not symmetric.

InstrumentsUsing an ad hoc questionnaire, we collected data on the caregivers’ sociodemographic characteristics, including their age, level of education, occupational status, civil status, household size, whether or not they had hobbies, as well as the duration of caregiving (in years), time devoted to caregiving (in hours per day), time spent on leisure activities and free time (in hours per week), and whether they had any chronic illnesses.

The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI; originally developed by Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, 1980) was designed to quantify burden in caregivers of dependent individuals. It explores the negative impact of caregiving on the caregiver in different areas of their life: physical health, mental health, social participation and financial resources. It consists of 22 items in question form, and the caregiver is asked to respond using a 5-point Likert-type scale (0=Never; 1=Rarely; 2=Sometimes; 3=Quite frequently; 4=Nearly always).

The overall score is the sum of all items, ranging from 22 to 110, and it can be used to assess whether or not the caregiver experiences burden and the level of burden: the higher the score, the higher the burden. In our study, we used the cut-offs proposed for the Spanish version (Martín et al., 1996): 22–46 (no burden), 47–55 (low burden) and 56–110 (high burden). The factors identified for this scale are: (1) Impact of care, including the items related to all issues associated with the effects of providing care on the caregiver, with a factor loading of 7.3, explaining 33.2% of the variance; (2) Interpersonal relationships, containing items referring to the relationship between caregiver and care recipient, with a factor loading of 2.5, explaining 11.4% of the variance; and (3) Expectations of self-efficacy, gathering items reflecting the beliefs and expectations of the caregiver about their own ability to care for the care recipient, with a factor loading of 2.1, explaining 9.7% of the variance. Regarding reliability, the data from the current research have shown good levels of internal consistency for the overall scale (α=.91) and for separate factors: Impact of care (α=.93), Interpersonal relationships (α=.87), and Expectation of self-efficacy (α=.77).

The 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) from the Medical Outcomes Survey provides a subjective measure of health status and is useful for assessing health-related quality of life. It assesses eight dimensions of health: physical functioning (the extent to which health limits physical activity or makes it difficult), physical role (the extent to which physical health interferes with work or other regular daily activities), social functioning (the extent to which physical health and emotional problems interfere with social activities), bodily pain (the intensity of pain experienced), mental health (general mental health), emotional role (the extent to which emotional problems interfere with work or activities of daily living), vitality (general feelings of energy and vitality), and general health (overall heath score) (Monteagudo, Hernando, & Palomar, 2011).

For each dimension, the items are recoded and summed, and the raw score obtained is transformed to a scale from 0 (worst health) to 100 (best health), providing a health status profile based on the scores obtained in each of the 8 dimensions. These eight dimensions can be aggregated into two measures, the physical and mental component summary scores. With respect to the reliability of this survey, the internal consistency ranges from .72 to .89, and the test-retest reliability from .73 to .86. The results published on metric characteristics provide evidence of its reliability, validity and sensitivity (Cronbach's alpha >.7). In our study, the internal consistency of the subscales ranged between .71 and .82.

The Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) is a brief multidimensional self-administered questionnaire, composed of items that are easy to understand, that allows us to assess both quantitative (social network size) and qualitative (dimensions of social support) aspects of support. It consists of 20 items, the first assessing structural support and the others functional support. Specifically, it explores five dimensions of social support: emotional support, information support, tangible support, positive social interaction and affectionate support. The interviewee is asked to rate on a 5-point scale how often each type of support is available if needed. Factor analysis has indicated that the emotional and information items should be combined, leaving four factors, for which independent scores can be obtained: emotional support, tangible support, positive social interaction and affectionate support. This scale has good psychometric properties. The internal consistency with other data in the current study was high, with alpha coefficients of .96 for emotional support, .85 for tangible support and .89 for positive social interaction.

ProcedureParticipants were recruited through a formal letter explaining the objectives of the research and providing general information on the study, the contact persons, the entity that carried it out and details concerning the ethics and confidentiality. This study follows the ethical procedures consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013). After reading this introductory information, women were invited to complete the questionnaires individually.

In order to achieve the greatest sincerity in the responses, at the top of the questionnaires, women were reminded of their anonymity in their answers. It was also noted that there were no good or bad answers, but rather different ways of relating to others.

In order to guarantee anonymity, each participant was given an envelope containing the letter and questionnaire; it also contained a thank you for participating in the research. In the same way, personnel trained for the research collected the questionnaire in a closed envelope. An online version of the questionnaire was also used and an equivalent procedure was followed for preserving anonymity.

For returning the questionnaire, participants were given a pre-addressed postage-paid envelope, that is, it bore the address to which the questionnaire had to be sent and could be deposited in any mailbox at no cost to the participant.

With the aim of obtaining a representative sample, this questionnaire was distributed between November 2014 and February 2015 to various different women's groups (members of women's associations) identified by consensus among several experienced professionals. Representatives of these groups were subsequently contacted by telephone to check that the questionnaires had been received and to discuss any concerns they had about their completion or return.

Data analysisFirst, a descriptive analysis was made of the health of the participating female caregivers. Second, correlations between social support, caregiver burden, and health were assessed using Pearson's r. Third, correlations between sociodemographic data, health, caregiver burden and social support were also assessed using Pearson's r. The differences in the mean scores in the dimensions of social support were then analysed. The effect size was interpreted as described by Cohen (1992) in the following way: values under .20 were considered small, those around .50 medium and those higher than .80 large. Finally, the mediating role of social support in the relationship between caregiver burden and health was explored.

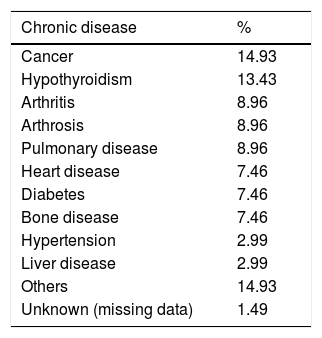

ResultsDescriptive data on the health of the sampleFirst, we performed a descriptive analysis of the variables associated with health (Table 2).

Descriptive data concerning the health of the female caregivers.

| Chronic disease | % |

|---|---|

| Cancer | 14.93 |

| Hypothyroidism | 13.43 |

| Arthritis | 8.96 |

| Arthrosis | 8.96 |

| Pulmonary disease | 8.96 |

| Heart disease | 7.46 |

| Diabetes | 7.46 |

| Bone disease | 7.46 |

| Hypertension | 2.99 |

| Liver disease | 2.99 |

| Others | 14.93 |

| Unknown (missing data) | 1.49 |

With regards to self-reported health, the highest scores were obtained for: the extent to which health limits physical activity or makes it difficult (mean of 92.63); the extent to which emotional problems interfere with work or activities of daily living (mean of 73.03); general feelings of energy and vitality (mean of 53.75); the extent to which physical health interferes with work or other regular daily activities (mean of 52.89); and overall health status (mean of 51.09). At the other extreme, the lowest scores were obtained for general mental health status (mean of 43.28), the extent to which physical health or emotional problems interfere with social activities (mean of 35.89), and the intensity of bodily pain experienced (mean of 28.33).

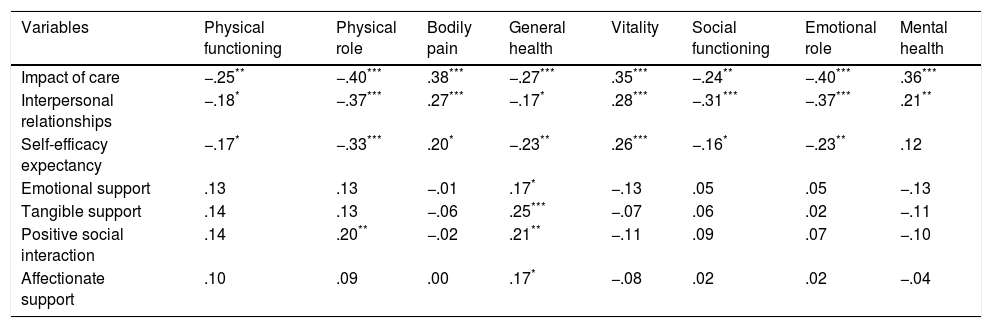

Relationship between social support, caregiver burden and healthAs can be observed, in general terms, general health was significantly negatively associated with caregiver burden and positively associated with social support. In addition, Physical role was negatively associated with the burden of care, as were emotional role and social functioning (Table 3).

Correlation between social support, caregiver burden and health.

| Variables | Physical functioning | Physical role | Bodily pain | General health | Vitality | Social functioning | Emotional role | Mental health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of care | −.25** | −.40*** | .38*** | −.27*** | .35*** | −.24** | −.40*** | .36*** |

| Interpersonal relationships | −.18* | −.37*** | .27*** | −.17* | .28*** | −.31*** | −.37*** | .21** |

| Self-efficacy expectancy | −.17* | −.33*** | .20* | −.23** | .26*** | −.16* | −.23** | .12 |

| Emotional support | .13 | .13 | −.01 | .17* | −.13 | .05 | .05 | −.13 |

| Tangible support | .14 | .13 | −.06 | .25*** | −.07 | .06 | .02 | −.11 |

| Positive social interaction | .14 | .20** | −.02 | .21** | −.11 | .09 | .07 | −.10 |

| Affectionate support | .10 | .09 | .00 | .17* | −.08 | .02 | .02 | −.04 |

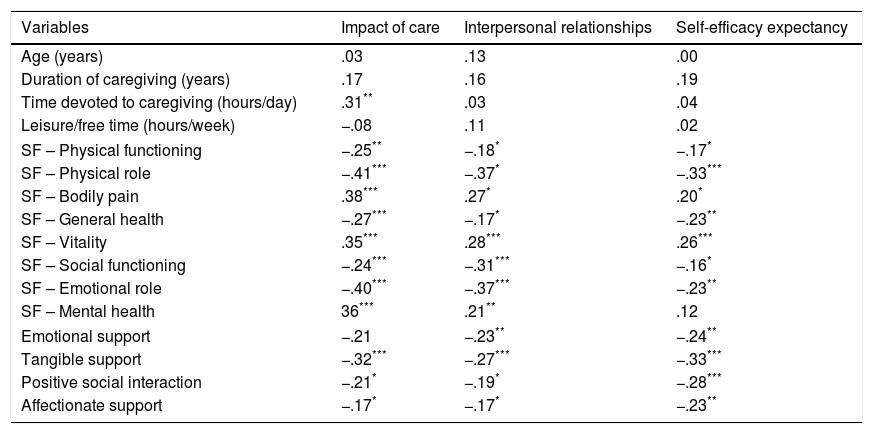

The results have shown that time devoted to caregiving correlates negatively with the impact of care. In addition, social support is negatively related to the burden of care (Table 4).

Correlation of burden with sociodemographic characteristics, health, and social support.

| Variables | Impact of care | Interpersonal relationships | Self-efficacy expectancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | .03 | .13 | .00 |

| Duration of caregiving (years) | .17 | .16 | .19 |

| Time devoted to caregiving (hours/day) | .31** | .03 | .04 |

| Leisure/free time (hours/week) | −.08 | .11 | .02 |

| SF – Physical functioning | −.25** | −.18* | −.17* |

| SF – Physical role | −.41*** | −.37* | −.33*** |

| SF – Bodily pain | .38*** | .27* | .20* |

| SF – General health | −.27*** | −.17* | −.23** |

| SF – Vitality | .35*** | .28*** | .26*** |

| SF – Social functioning | −.24*** | −.31*** | −.16* |

| SF – Emotional role | −.40*** | −.37*** | −.23** |

| SF – Mental health | 36*** | .21** | .12 |

| Emotional support | −.21 | −.23** | −.24** |

| Tangible support | −.32*** | −.27*** | −.33*** |

| Positive social interaction | −.21* | −.19* | −.28*** |

| Affectionate support | −.17* | −.17* | −.23** |

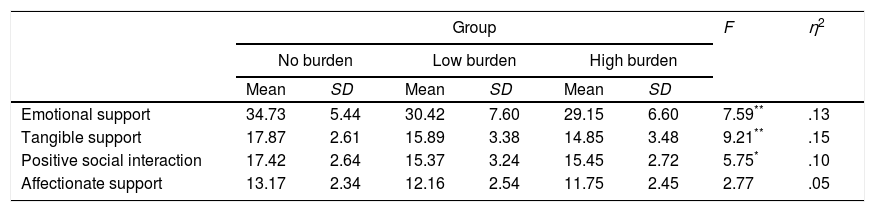

Finally, we analysed differences across the dimensions of social support.

In the multivariate analysis, we observed a significant effect for the independent variable, F(8, 208)=2.81, p=.006, η2=.10, but none for the covariate, F(4, 103)=1.95, p=.107, η2=.07. As can be observed, in the three cases in which we found significant differences, the “No burden” group obtained higher scores than the other two groups. The effect sizes were moderate to large. Bonferroni's Post-Hoc test showed statistically significant differences in emotional support, instrumental support and positive social interactions, people with higher levels of caregiving burden scoring lower than people with low caregiving burden or no caregiving burden (Table 5).

Univariate differences in social support by burden group.

| Group | F | η2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No burden | Low burden | High burden | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Emotional support | 34.73 | 5.44 | 30.42 | 7.60 | 29.15 | 6.60 | 7.59** | .13 |

| Tangible support | 17.87 | 2.61 | 15.89 | 3.38 | 14.85 | 3.48 | 9.21** | .15 |

| Positive social interaction | 17.42 | 2.64 | 15.37 | 3.24 | 15.45 | 2.72 | 5.75* | .10 |

| Affectionate support | 13.17 | 2.34 | 12.16 | 2.54 | 11.75 | 2.45 | 2.77 | .05 |

Note. We applied the Bonferroni post hoc test.

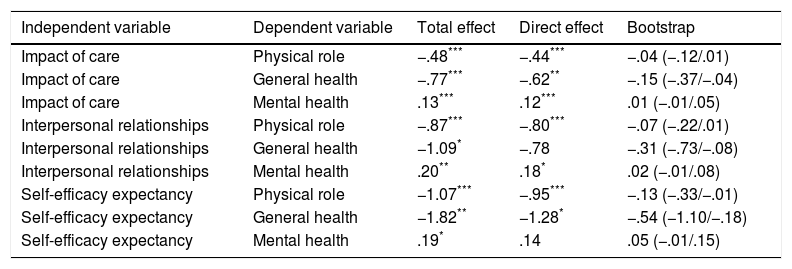

From the results obtained in the previous steps, we analysed the potential indirect relationship between female caregiver burden and health, considering social support as a potential mediator in the relationship. Specifically, we conducted mediation analyses based on correlation results, in all cases, introducing the factor score obtained by principal component analysis as the mediating variable.

To investigate mediating effects, we considered the overall effect and the direct effect of social support, caregiver burden and health. Further, the indirect effects were assessed with a bootstrapping technique, using 95% confidence intervals. For this, 5000 subsamples were generated by resampling, with a bias-corrected estimation method. It was considered that there was a significant mediating effect when the confidence interval of the indirect effect did not span zero. The results are reported in Table 6.

Mediation analysis of the indirect effect of caregiver burden on health, investigating social support as a potential mediating variable.

| Independent variable | Dependent variable | Total effect | Direct effect | Bootstrap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of care | Physical role | −.48*** | −.44*** | −.04 (−.12/.01) |

| Impact of care | General health | −.77*** | −.62** | −.15 (−.37/−.04) |

| Impact of care | Mental health | .13*** | .12*** | .01 (−.01/.05) |

| Interpersonal relationships | Physical role | −.87*** | −.80*** | −.07 (−.22/.01) |

| Interpersonal relationships | General health | −1.09* | −.78 | −.31 (−.73/−.08) |

| Interpersonal relationships | Mental health | .20** | .18* | .02 (−.01/.08) |

| Self-efficacy expectancy | Physical role | −1.07*** | −.95*** | −.13 (−.33/−.01) |

| Self-efficacy expectancy | General health | −1.82** | −1.28* | −.54 (−1.10/−.18) |

| Self-efficacy expectancy | Mental health | .19* | .14 | .05 (−.01/.15) |

Note: R2=.22.

As can be observed, we found that social support had significant mediating effects on the relationships between Impact of care and General health, Interpersonal relationships and General Health, Self-efficacy expectancy and Physical Role, and Self-efficacy Expectancy and General Health.

DiscussionFirstly, we analysed the physical, mental and general health of female caregivers. Overall, 27.2% of women in our sample had at least one chronic condition. It was very common that they felt their health limited or hampered physical activities, and that emotional changes affected work or activities of daily life. Physical health and emotional problems seem to interfere with caregivers social functioning. In relation to these data, previous studies have reported higher rates of chronic diseases among female caregivers, with a rate as high as 44%, and poorer perceived emotional health than physical health (Jofré & Mendoza, 2005).

Secondly, we analysed the relationship between health, social support and caregiver burden. Our data indicate that the greater the perceived burden, the poorer the self-reported general health of the caregivers. These results are in line with those obtained in previous studies that have found the same pattern, highlighting the importance of perceived health in caregivers, especially with regards to mental health (Fernández de Larrinoa et al., 2011).

Further, caregiver burden seems to be positively associated with pain, vitality and mental health; we have found that the greater burden, the greater the vitality, mental health and perceived intensity of pain. This positive association of burden with vitality and mental health is inconsistent with previous research that has indicated negative consequences for the physical and mental health of caregivers for dependent individuals (Butterworth, Pymont, Rodgers, Windsorm, & Anstey, 2010). Some authors even describe a clinical condition encompassing the set of health problems likely to be found in caregivers, calling it “caregiver syndrome” (García-Calvente et al., 2004). This may be due to the fact that we have analysed female caregivers in general. In other words, the scope of informal caregiving as understood for this study includes tasks that the women may consider a normal part of their activities of daily living; and given that not all the tasks are related to dependent or ill individuals, effects from the associated burden though present are not large.

In this study, burden has been found to be negatively associated with Physical functioning, Physical Role, Social functioning and Emotional Role. This means the greater the perceived burden, the poorer the physical and social function, making women feel that both physical health and emotional problems have an impact on their health. In line with this, previous studies have indicated that caregivers report a loss of friends, negative physical health effects, and psychological symptoms, such as feelings of sadness (Jofré & Mendoza, 2005), depression and anxiety (Geng et al., 2018; Vérez, Andrés, Fornos, Andrés, & Ríos, 2015). With regards to social support, the results show that the lower the emotional, tangible, and affectionate support and the positive social interaction, the greater the perceived burden; and that the lower the social support, the poorer the general health of the women. These results are in line with previous research finding that social support reduces burden (Flórez, Montalvo, & Romero, 2012) and has a positive effect on the wellbeing of informal caregivers (Fernández-Ballesteros, 2009).

Finally, we analysed the potential indirect relationship between caregiver burden and health, considering social support as a potential mediator. The results obtained show that social support does mediate in the relationship between Impact of care and General health; Interpersonal relationships and General health; Self-efficacy Expectancy and Physical Role, and lastly, Self-efficacy Expectancy and General health. These results support the findings of Olshevski, Katz, and Knight (1999), indicating that perceived social support can act as a buffer against stress in caregivers. Authors such as Crespo and López (2008) point to coping strategies and social support as mediators of the wide range of ways in which the caregiving role may affect an individual. Specifically, a lack of social support is then identified as a mediator that explains poorer physical and mental health in caregivers, and as such, a factor that is potentially modifiable through interventions (Butterworth et al., 2010). This underlines the need to design and implement programmes to detect and intervene in burden in caregivers, including monitoring, creation of forums to provide guidance and support, and the strengthening of coping strategies (Flores & Arcos, 2014; Leal, Sales, Ibañez, Giner, & Leal, 2008; López & Crespo, 2007; Sánchez, Molina, & Gómez-Ortega 2016; Velásquez, López, López, Cataño, & Muñoz, 2011).

The study has certain limitations. Firstly, there are limitations related to the nature of the sample, obtained by convenience sampling from one region of our country and composed exclusively of women, with a mean age of 58 years. In addition, most of them have university or vocational training and almost half worked in sectors such as administration, health or education. In particular, the elevated age might not be representative of caregivers and restricts the generalisation of the findings. Along these lines, we are dealing with a very heterogeneous sample of women, in which certain variables such as the age of the children (and whether or not they are still under the care of women), the socio-economic and cultural-educational level of the participants, or their possible effects on the mediation analysis have not been controlled for. While acknowledging this heterogeneity and the limitations it entails, we underline that the objective was related to women and caregiving, the latter being the key variable of the study. Studies on caregiving have not previously been carried out with this type of sample, making the results particularly interesting. We found evidence from both younger and older women that supports the perspective that the caregiving role transcends age, because it is linked to gender. On the other hand, we should mention that the women were recruited through women's associations, and being part of such groups may be associated with higher levels of social support. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the study means that causality cannot be determined in the associations found between study variables.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the data provided in this study underlines the high level of burden in caregivers, as well as its association with health and the potential role of social support in buffering against this burden. The impact of caregiving on health and social activities of female caregivers makes it necessary for programmes designed to provide support and care for caregivers to include, in addition to information and training, a care plan and psychological support for caregivers (Cerquera & Pabón, 2016; Dawson et al., 2017), placing particular emphasis on self-care (Ferrer et al., 2012). Looking after themselves is as important as caring for the care recipient (Melo De Souza, Wegner, & Pinto, 2007), but for this to be possible for caregivers, they need to make time for themselves, and in the domestic setting, it can be difficult to find time for self-care (Murillo, 1996). The need to care for one's health needs to be seen as a societal problem, to favour an improvement in the quality of life of female caregivers who are a vulnerable group, and enable them to assert their right to a reduction in the caregiver burden and the associated risks for their health (Vaquiro & Stiepovich, 2010). Finally, it should be noted that the sample of women do not define themselves as caregivers since they have only taken into account the hours of care in which they care for a dependent person, instead of defining care work in a global manner, integrating logistics and organization issues, among others. The fact that almost half of the women did not know who they cared for could be because they do not consider that they are caring while making food for other people, organizing the household chores, asking for a medical appointment on behalf of someone else or making the shopping list. In this sense, the women in the study have only taken into account the hours of care in which they care for a dependent person, instead of defining care work in a global manner integrating logistics, organization and surveillance issues, among others. These are actions that have not been taken into account when answering the two sociodemographic questions asked that are related to care. Therefore, they only consider that they have been caregivers for half of their lives. It is necessary to carry out studies that continue to explore the question of what is perceived as care and improve our understanding of the caregiving process.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.