The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence and risk factors of allergic diseases in preschool children from one of the biggest cities in the Mediterranean Region of Turkey.

MethodsThe study population included 396 preschool children attending to urban daycare centres in Mersin. In the first stage, a comprehensive standardised questionnaire modified from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) was employed. In the second stage, serum food and inhalant specific IgE, and skin tests were performed in 45 children with frequent wheezing and 28 children with no wheezing.

ResultsThe prevalence of ever wheezing, current wheezing, physician-diagnosed asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema were 53% (210), 33.3% (132), 27.3% (108), 13.4% (53) and 8.3% (33), respectively. A family history of atopy (OR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.3–4.7, p=0.004), dampness at home (OR=2.4, 95% CI: 1.2–4.8, p=0.008), a history of intestinal parasites (OR=4.3, 95% CI: 1.7–10.9, p=0.002), previous history of pneumonia (OR=6.9, 95% CI: 1.9–25.9, p=0.004), initiation of complementary foods before the age of three months (OR=6.1, 95%CI: 1.4–26.9, p=0.02) and presence of food allergy (OR=3.1, 95% CI: 1.1–9.2, p=0.03) were found to be significant risk factors for physician-diagnosed asthma. The risk factors for frequent wheezing were maternal smoking during pregnancy (OR=5.2, 95% CI: 0.9–28.7, p=0.05) and high serum IgE levels (OR=2.9, 95% CI: 0.9–9.0, p=0.05) at borderline significance.

ConclusionOur study was the first epidemiological study in preschool children in the Mediterranean region of Turkey and demonstrated a high prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases, probably related to humid climatic properties in addition to other environmental and genetic factors.

Asthma and allergic diseases are among the most common chronic disorders in children. A significant increase in the prevalence of allergic diseases has been observed in recent years.1,2 The results of studies investigating the prevalence of allergic diseases in different countries indicate significant differences. This may be related to different methods used in prevalence studies. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), the most comprehensive global study on the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases in children, has introduced a standardisation for epidemiological research.3 According to the ISAAC Phase three study, the global prevalence for current asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema in the 6–7 years age group was 11.7%, 8.5% and 7.9%, respectively.4

Although many epidemiological studies related to asthma and allergic diseases are reported in school-age children,2,4 there is still limited data on the prevalence of respiratory and allergic diseases in preschool children. The epidemiological evaluation of the prevalence of respiratory and allergic diseases in 3–5 years aged children attending nursery schools demonstrated that 15% of children experienced at least one episode of wheezing, 5.5% of allergic rhinitis, 11% of children had a doctor diagnosis of asthma, 12% of children diagnosed as atopic.5 A previous study from Italy found that the prevalence of “wheezing in previous 12 months” and “doctor-diagnosed asthma” in preschool children were 12.1% and 8.6%, respectively.6 The prevalence of rhinitis in the last 12 months was found as 16.8% in preschool children.7

Allergic diseases are multifactorial which are influenced by various genetic and environmental factors. Since it seems unlikely that genetic factors contribute to the increasing trend, environmental factors might play an important role in the development of asthma and allergic diseases.8 The increase in allergic diseases in recent years can probably be explained by the change of lifestyles such as indoor air pollution, parental smoking, pet keeping, daycare attendance, respiratory tract and intestinal helminth infections, number of siblings, breastfeeding, and dietary habits affecting the immune system in the early stages of life.8–10

The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence and risk factors of respiratory and allergic diseases using a modified ISAAC questionnaire in preschool children attending daycare centres in the city of Mersin. This will be the first epidemiological study for respiratory and allergic diseases among the paediatric age group living in our city.

Materials and methodsStudy designThe present study comprised two phases. Phase 1 was a prevalence study aimed to determine the prevalence of allergic diseases and risk factors by a modified ISAAC questionnaire. Phase 2 was the case–control study aimed to investigate the risk factors of children with frequent wheezing, including objective tests in addition to the questionnaire.

Study populationThe study population comprised all children attending daycare centres in the city centre who were randomly selected from the list of all daycare centres in Mersin from January to December 2011. The modified ISAAC questionnaires were distributed to and collected through all children in these daycare centres. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Mersin University, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participating children.

Data collectionPhase 1A modified ISAAC questionnaire was used to assess the symptoms of allergic and respiratory diseases, and the potential risk factors for the outcomes.11 Basic ISAAC questions about respiratory symptoms and diagnosis, which have been previously validated in our country and other countries11–13 were not changed in this study. The modifications were related to cultural and geographic risk factors which included: Vitamin D supplementation status, entrance of some weaning foods such as yoghurt and milky biscuits, parasitosis history, presence of dampness and mould which are greatly anticipated in this humid Mediterranean region. The questionnaire included questions about the symptoms and diagnosis of respiratory diseases, eczema, food allergy and risk factors such as demographic characteristics, gestational factors, family history, feeding practices, household characteristics such as house crowding, presence of pets, dampness, and tobacco smoke exposure. The parents filled out the modified ISAAC questionnaire at home and returned it in a few days.

The prevalence of respiratory and allergic diseases were sought based on positive answers to these questions: (1) ‘Has your child ever had symptoms?’ (symptom, ever); (2) ‘Has your child had symptoms in the last 12 months?’ (symptom, last 12 months); (3) ‘Has your child ever been diagnosed by a physician as having the disorder?’ (physician diagnosed); (4) ‘Has your child been treated by a physician for the disorder in the last 12 months?’ (treatment, last 12 months). “Current” was defined as a positive response to ‘symptom, in the last 12 months.’ Frequent wheeze was defined as three or more episodes of wheezing observed by the parents in the last 12 months. Rhinitis was defined as a problem with sneezing, or a runny or blocked nose, when the child did not have a cold or flu. Children whose parents reported an itchy rash for at least six months were labelled as having eczema. Food allergy was defined as the parents responding yes to the question 'Has your child had allergic symptoms after ingesting some foods?”. Family atopy was defined as a positive history of rhinitis, asthma and eczema in one or both of the parents. Bronchitis, otitis and laryngitis were defined as a history of bronchitis, otitis and/or laryngitis diagnosed by physician, respectively. A history of mouth breathing and snoring reported by parents was also defined as mouth breathing. Treatment for wheezing, rhinitis and eczema was defined as a history of treatment by a physician for wheezing, rhinitis and/or eczema including bronchodilators, inhaled or oral steroids, antileukotrienes, nasal steroids, antihistamines, topical steroids and moisturisers in the last 12 months.

Phase 2In order to reveal the relation of atopic sensitisation to wheezing recurrence, all children with frequent wheezing and a control group of twenty-eight children selected randomly from children without any wheezing history were invited to the paediatric allergy clinic. Sensitisation was ascertained by skin prick test (SPT). It was performed according to the ISAAC protocol.14 The following inhalant and food antigens were applied in addition to histamine and saline controls: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, cat and dog dander, Alternaria alternata, cockroach, mixed grass, tree pollen, cow's milk, hen's egg, soy, wheat, fish and nuts mixture. A positive skin prick test was defined as a mean diameter of wheal at least 3mm larger than the negative control with surrounding erythema.

Serum total IgE levels and absolute eosinophil counts were measured as markers of an allergy. Specific IgE antibodies to food mix including cow's milk, hen's egg, wheat, soy, fish, peanut and inhalant allergens were measured using ImmunoCap (Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden). Results ≥0.35kU/L were accepted as positive. The stool was examined for parasites.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 11.5.1 statistical software for Windows. Descriptive statistics were calculated including means, standard deviations, frequencies and medians. Comparisons for continuous variables were made by the Independent Samples t test and categorical variables were compared by the chi-square test. Variables considered as possible risk factors for wheezing and allergic diseases in univariate analysis (p value <0.10) were introduced into the multivariate regression model. A logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the associations between allergic diseases and clinical characteristics. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

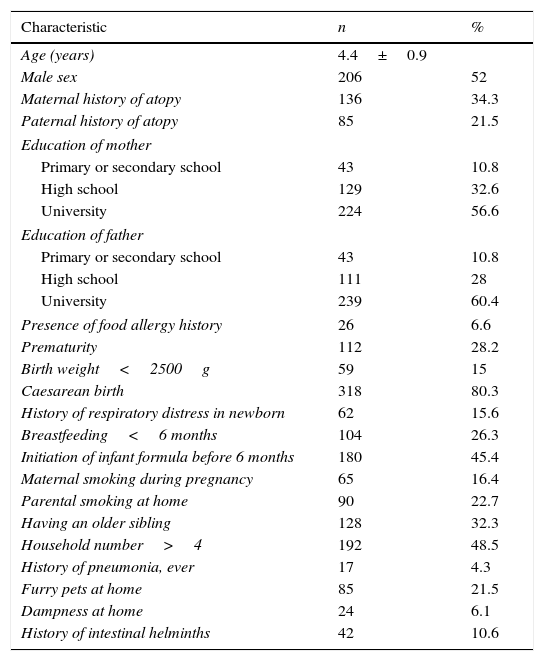

ResultsThe clinical characteristics of children and the prevalence of atopic diseasesFrom a total of 612 children, to whom the questionnaire was distributed, 396 (65%) children returned the questionnaire. Of the children, 52% (206) were boys. The mean age of the participants was 4.4±0.9 years. 56.5% (224) of mothers and 60.4% (239) of fathers had academic education. The history of atopic disease was present in 34.3% of mothers and 21.5% of fathers. Of all the children, 26.3% (104) had been breastfed less than six months. The rate for the initiation of infant formula before six months was 45.4% (180). The mean age for starting daycare centre was 3.1±1 years. Overall, 16.4% (65) of the mothers smoked during pregnancy and 22.7% (90) of the parents smoked indoors at home. Of the children, 21.5% (85) had furry pets, 6.1% (24) had dampness at home. The clinical and environmental characteristics of children are shown in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the children (n=396).

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 4.4±0.9 | |

| Male sex | 206 | 52 |

| Maternal history of atopy | 136 | 34.3 |

| Paternal history of atopy | 85 | 21.5 |

| Education of mother | ||

| Primary or secondary school | 43 | 10.8 |

| High school | 129 | 32.6 |

| University | 224 | 56.6 |

| Education of father | ||

| Primary or secondary school | 43 | 10.8 |

| High school | 111 | 28 |

| University | 239 | 60.4 |

| Presence of food allergy history | 26 | 6.6 |

| Prematurity | 112 | 28.2 |

| Birth weight<2500g | 59 | 15 |

| Caesarean birth | 318 | 80.3 |

| History of respiratory distress in newborn | 62 | 15.6 |

| Breastfeeding<6 months | 104 | 26.3 |

| Initiation of infant formula before 6 months | 180 | 45.4 |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | 65 | 16.4 |

| Parental smoking at home | 90 | 22.7 |

| Having an older sibling | 128 | 32.3 |

| Household number>4 | 192 | 48.5 |

| History of pneumonia, ever | 17 | 4.3 |

| Furry pets at home | 85 | 21.5 |

| Dampness at home | 24 | 6.1 |

| History of intestinal helminths | 42 | 10.6 |

Values are presented as mean (±standard deviation) or number (%).

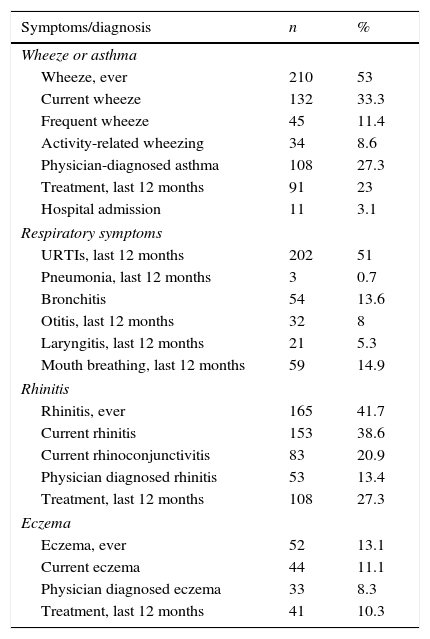

The prevalence of wheezing ever, wheezing over the last 12 months, and physician-diagnosed asthma were 53% (210), 33.3% (132) and 27.3% (108), respectively. The prevalence of rhinitis ever, rhinitis over the last 12 months, current rhinoconjunctivitis and physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis were 41.7% (165), 38.6% (153), 20.9% (83) and 13.4% (53), respectively. The rate of dry skin lesions ever was 21.7% (86), eczema ever was 13.1% (52), current eczema was 11.1% (44) and physician-diagnosed eczema was 8.3% (33) (Table 2).

Descriptive results about symptoms and diagnosis in preschool children (n=396).

| Symptoms/diagnosis | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Wheeze or asthma | ||

| Wheeze, ever | 210 | 53 |

| Current wheeze | 132 | 33.3 |

| Frequent wheeze | 45 | 11.4 |

| Activity-related wheezing | 34 | 8.6 |

| Physician-diagnosed asthma | 108 | 27.3 |

| Treatment, last 12 months | 91 | 23 |

| Hospital admission | 11 | 3.1 |

| Respiratory symptoms | ||

| URTIs, last 12 months | 202 | 51 |

| Pneumonia, last 12 months | 3 | 0.7 |

| Bronchitis | 54 | 13.6 |

| Otitis, last 12 months | 32 | 8 |

| Laryngitis, last 12 months | 21 | 5.3 |

| Mouth breathing, last 12 months | 59 | 14.9 |

| Rhinitis | ||

| Rhinitis, ever | 165 | 41.7 |

| Current rhinitis | 153 | 38.6 |

| Current rhinoconjunctivitis | 83 | 20.9 |

| Physician diagnosed rhinitis | 53 | 13.4 |

| Treatment, last 12 months | 108 | 27.3 |

| Eczema | ||

| Eczema, ever | 52 | 13.1 |

| Current eczema | 44 | 11.1 |

| Physician diagnosed eczema | 33 | 8.3 |

| Treatment, last 12 months | 41 | 10.3 |

Values are presented as number (%).

URTIs: Upper respiratory tract infections.

The prevalence of physician-diagnosed upper respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, bronchitis, otitis, and laryngitis over the last 12 months were 51% (202), 0.7% (3), 13.6% (54), 8% (32), and 5.3% (21), respectively. The prevalence of mouth breathing and snoring was 14.9% (59) (Table 2).

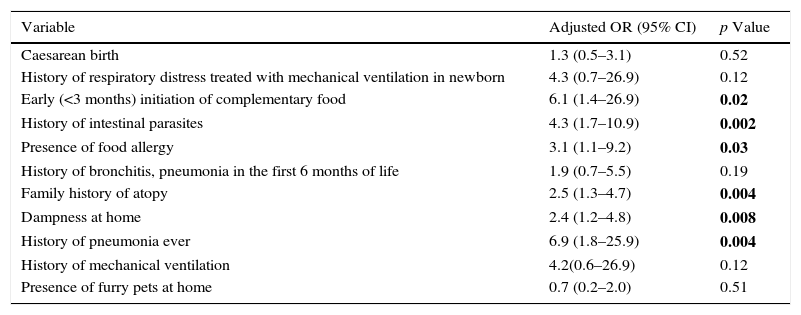

Risk factors associated with allergic diseasesAccording to the univariate analysis, a history of bronchitis or pneumonia in the first six months of life (p=0.002), the history of food allergy (p=0.008), intestinal parasites (p=0.02) and family atopy (p=0.001) were found to be related to physician-diagnosed asthma. In multivariate analysis, a family history of atopy (OR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.3–4.7, p=0.004), dampness at home (OR=2.4, 95% CI: 1.2–4.8, p=0.008), the history of intestinal parasites (OR=4.3, 95% CI: 1.7–10.9, p=0.002), pneumonia ever (OR=6.9, 95% CI: 1.9–25.9, p=0.004), initiation of complementary foods before the age of three months (OR=6.1, 95% CI: 1.4–26.9, p=0.02) and presence of food allergy history (OR=3.1, 95% CI: 1.1–9.2, p=0.03) were found to be independent and significant risk factors for the physician-diagnosed asthma (Table 3).

Risk factors for physician-diagnosed asthma in multivariate analysis.

| Variable | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Caesarean birth | 1.3 (0.5–3.1) | 0.52 |

| History of respiratory distress treated with mechanical ventilation in newborn | 4.3 (0.7–26.9) | 0.12 |

| Early (<3 months) initiation of complementary food | 6.1 (1.4–26.9) | 0.02 |

| History of intestinal parasites | 4.3 (1.7–10.9) | 0.002 |

| Presence of food allergy | 3.1 (1.1–9.2) | 0.03 |

| History of bronchitis, pneumonia in the first 6 months of life | 1.9 (0.7–5.5) | 0.19 |

| Family history of atopy | 2.5 (1.3–4.7) | 0.004 |

| Dampness at home | 2.4 (1.2–4.8) | 0.008 |

| History of pneumonia ever | 6.9 (1.8–25.9) | 0.004 |

| History of mechanical ventilation | 4.2(0.6–26.9) | 0.12 |

| Presence of furry pets at home | 0.7 (0.2–2.0) | 0.51 |

A total of 11 variables considered as possible risk factors for physician-diagnosed asthma (in univariate analysis p value<0.10) were introduced into the multivariate regression model.

OR: odds ratio.

CI: confidence interval.

p values in bold are statistically significant.

The risk factors for physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis were age (p=0.009), food allergy (p=0.04) and a family history of atopy (p=0.001) in univariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, the significant risk factors for physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis were age (OR=0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.9, p=0.005) and family history of atopy (OR=3.2, 95% CI: 1.7–6.3, p=0.001). No significant risk factor was found for physician-diagnosed atopic dermatitis.

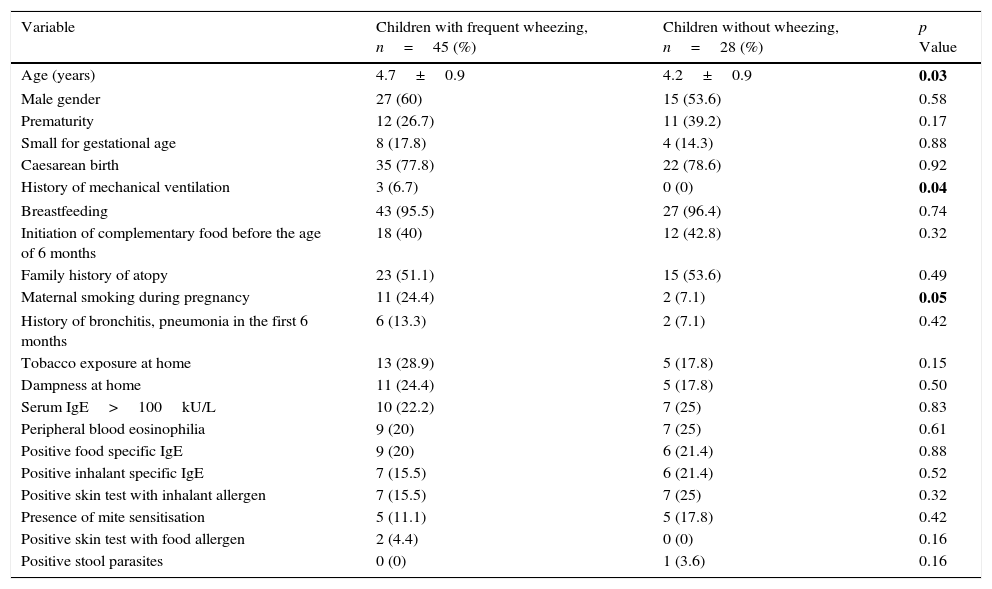

Risk factor analysis for frequent wheezing included SPT, food and inhalant specific IgE, total IgE, eosinophil count and stool parasite results, in addition to questions about risk factors from the questionnaire. Age (p=0.03), maternal smoking during pregnancy (p=0.05) and a history of treatment with mechanical ventilation in newborn period (p=0.04) were found to be significantly related to frequent wheezing (Table 4). In multivariate analysis, the risk factors for frequent wheezing were found as maternal smoking during pregnancy (OR=5.2, 95% CI: 0.9–28.7, p=0.05) and serum IgE levels (OR=2.9, 95% CI: 0.9–9.0, p=0.05) at borderline significance.

Risk factors for frequent wheezing.

| Variable | Children with frequent wheezing, n=45 (%) | Children without wheezing, n=28 (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 4.7±0.9 | 4.2±0.9 | 0.03 |

| Male gender | 27 (60) | 15 (53.6) | 0.58 |

| Prematurity | 12 (26.7) | 11 (39.2) | 0.17 |

| Small for gestational age | 8 (17.8) | 4 (14.3) | 0.88 |

| Caesarean birth | 35 (77.8) | 22 (78.6) | 0.92 |

| History of mechanical ventilation | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 0.04 |

| Breastfeeding | 43 (95.5) | 27 (96.4) | 0.74 |

| Initiation of complementary food before the age of 6 months | 18 (40) | 12 (42.8) | 0.32 |

| Family history of atopy | 23 (51.1) | 15 (53.6) | 0.49 |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | 11 (24.4) | 2 (7.1) | 0.05 |

| History of bronchitis, pneumonia in the first 6 months | 6 (13.3) | 2 (7.1) | 0.42 |

| Tobacco exposure at home | 13 (28.9) | 5 (17.8) | 0.15 |

| Dampness at home | 11 (24.4) | 5 (17.8) | 0.50 |

| Serum IgE>100kU/L | 10 (22.2) | 7 (25) | 0.83 |

| Peripheral blood eosinophilia | 9 (20) | 7 (25) | 0.61 |

| Positive food specific IgE | 9 (20) | 6 (21.4) | 0.88 |

| Positive inhalant specific IgE | 7 (15.5) | 6 (21.4) | 0.52 |

| Positive skin test with inhalant allergen | 7 (15.5) | 7 (25) | 0.32 |

| Presence of mite sensitisation | 5 (11.1) | 5 (17.8) | 0.42 |

| Positive skin test with food allergen | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 0.16 |

| Positive stool parasites | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 0.16 |

Values are presented as mean (±standard deviation) or number (%).

p values in bold are statistically significant.

This study was the first epidemiological study that investigated the prevalence and risk factors of respiratory and allergic diseases with a modified ISAAC questionnaire in preschool children in the Mediterranean region of Turkey. We demonstrated a high prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases probably related to environmental factors. The prevalence of wheezing ever, current wheezing and physician-diagnosed asthma were 53%, 33.3% and 27.3%, respectively. The prevalence of rhinitis ever, current rhinitis and physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis were 41.7%, 38.6% and 13.4%, respectively. The prevalence of eczema ever was 13.1%, current eczema was 11.1% and physician-diagnosed eczema was 8.3%.

Worldwide ISAAC Phase 3 study revealed that the prevalence for current asthma was 11.7% in the 6–7 years old children.4 A previous report from Turkey showed the prevalence of wheezing, current wheezing and physician-diagnosed asthma in preschool children were 23.3%, 8.6% and 4.1%, respectively.15 The prevalence of ever wheezing, current wheezing and physician-diagnosed asthma in the present study were higher than previous reports in preschool children.16,17 This higher prevalence of asthma diagnosis in our study may be related to environmental factors such as humid climatic properties of the region besides genetics.

ISAAC Phase 3 study demonstrated that the prevalence for rhinoconjunctivitis was 8.5% in the 6–7 years old children.4 A previous report from Turkey, found that the prevalence of lifetime, current and physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis in the 6–7 years aged children were 44.3%, 29.2% and 8.1%, respectively.18 The prevalence of rhinitis ever, rhinitis over the last 12 months and physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis in the present study were higher than that in children in most of Western countries13 and Korea.16

ISAAC Phase 3 study reported that the prevalence for eczema was 7.9% in 6–7 years old children.4 Baek et al., showed that the prevalence of atopic dermatitis over the previous 12 months in preschool children was 18%, which was comparable with our result.19 The prevalence of eczema ever, eczema over last 12 months and physician-diagnosed eczema in our study were lower than that in children in other countries.13,16

The ISAAC study has shown wide variations in prevalence of allergic diseases both within and between countries, suggesting that environmental factors may be critical in determining disease expression besides genetics.2 Previous studies reported that the presence of parental allergic diseases, caesarean delivery, number of family members, use of antibiotics, indoor humidity, and a history of bronchiolitis were the risk factors for allergic diseases.16,17

In our study, a family history of atopy, dampness at home, the history of intestinal parasites and pneumonia, initiation of complementary foods before the age of three months and the presence of food allergy were found to be independent and significant risk factors for physician-diagnosed asthma. The German Multicentre Allergy Study (MAS) reported that maternal asthma was the strongest risk factor for the development of childhood asthma.8 Dampness and mould growth in the home have been shown to be associated with wheeze and asthma in the ISAAC Phase II study.20 The studies on the role of parasites on asthma prevalence have been inconsistent.21–24 Previous studies have also provided contradictory evidence on the role of early childhood infections in the development of asthma and other allergic diseases during childhood.25,26 A recent study emphasised that the risk of developing asthma was more strongly associated with lower respiratory tract infections experienced at 1–2 years of age than with infections experienced later in childhood.27 In accordance with the literature,28 early initiation of complementary foods was found as a significant risk factor for asthma in our study. Also in agreement with other investigators, we found that the presence of food allergy was a significant risk factor for asthma in preschool children.29,30 Although many articles reported the protective effect of Mediterranean diet on wheezing and allergic diseases, we could not evaluate this factor since most of the children consumed a similar diet rich in Mediterannean food.31–33

The significant risk factors for physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis were age and family history of atopy in our study. The ISAAC Phase II study demonstrated that a family atopy, dampness/mould at one year of age and heating with gas stove were significantly associated with current rhinitis among school children.34 Peroni et al., reported that a family history of atopy, having pets at home, male gender and greater age were risk factors for rhinitis in preschool children.7

In the present study, the risk factors for frequent wheezing were maternal smoking during pregnancy and high serum IgE levels at borderline significance. This result suggested that the factors affecting the mechanical properties of airways at birth contribute more than the atopic inflammation for the development of frequent wheezing. The International Study of Wheezing in infants (EISL) showed that male gender, attending nursery school, first cold at ≤3 months, eczema, maternal asthma, exclusive breastfeeding for <3 months and maternal smoking during pregnancy were significantly associated with recurrent wheezing.35,36

The first limitation of our study was low participation rate. This may have resulted in involvement of children with more allergic symptoms and the families with higher socioeconomic levels and may have caused participation bias. Second, a clear relationship between disease development and individual characteristics and also environmental factors cannot be accurately demonstrated because of the cross-sectional design of the study.

Our study has some strengths. First, this study was the first epidemiological study about respiratory and allergic diseases in preschool children on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey. Second, the participants were evaluated by a detailed standardised questionnaire and objective tests. Moreover, considering the limited data on epidemiological studies of allergic diseases in preschool children in Turkey, this study has provided important additive results about the frequency and risk factors of asthma and allergic diseases.

In conclusion, our results suggested a high prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases in preschool children in a southern region of Turkey. Physician-diagnosed asthma and wheezing illness showed different risk profiles. Early childhood environmental exposures, such as early infant weaning and dampness/mould exposure may promote subsequent development of childhood asthma and allergic diseases. The information obtained from the current study can be used in the planning of health care strategies and the prevention programmes of allergic diseases.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest that may be inherent in this submission.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.