Wheezing in the first year of life affects the baby's and family's quality of life. Risk factors such as male gender, nursery attending or a family history of asthma, and protective factors such as breastfeeding more than six months have been previously described. The aim of this study is to study the prevalence and risk factors for wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing in the first year of life in infants in the region of Pamplona, Spain.

Material and methodsThis cross-sectional study was part of the International Study of Wheezing in Infants (Estudio Internacional de Sibilancias en Lactantes, EISL). Between 2006 and 2008, participating families answered a standardised validated questionnaire on respiratory symptoms, environmental factors or family issues. An analysis with the chi square test (statistical significance p<0.05) identified the risk factors for wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing, which were assessed using logistic regression.

Results1065 questionnaires were answered. The prevalence of wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing were 31.2% and 12.3%, respectively. Male gender (p=<0.001), a history of pneumonia (p=<0.001) or nursery attendance (p=<0.001) were some of the risk factors found for wheezing ever. Infant eczema (p=<0.001), nursery attendance (p=<0.001) or prematurity (p=<0.001) were risk factors for recurrent wheezing. No associations with duration of breastfeeding (p=0.116 and p=0.851) or mould stains at home (p=0.153 and p=0.992) were found.

ConclusionThe study of prevalence and risk factors for wheezing shows the importance of this public health problem, and allows the development of control and treatment strategies against preventable factors.

Wheezing in infants is an important problem, affecting children's health-related quality of life,1 and can lead to asthma in childhood.2,3

Prevalence of wheezing ever in infants varies across different regions, from 29% in countries in Northern Europe, to 48% in countries in Southern Europe, and 27% in the United States of America (USA).4 Previous studies have found associations between rainy weather and severe current wheeze in schoolchildren,5 and stronger associations of some risk and protective factors of recurrent wheezing when latitude increases.6

Several risk factors have been described, with the most important being male sex, familiar history of asthma, nursery attendance, history of pneumonia, smoking during pregnancy, mould stains in the house and breastfeeding fewer than six months.7–9 Protective factors such as breastfeeding more than eight months10 and adherence to the Mediterranean diet11 have been found.

Although previous studies about wheezing in infants have been conducted, none of them have studied the epidemiology of the disease in the North of Spain. The aim of this cross-sectional study is to examine the prevalence and risk factors of wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing in the first year of life in infants from the region of Pamplona.

Materials and methodsStudy populationThis study was part of the International Study of Wheezing in Infants (in Spanish, Estudio Internacional de Sibilancias en Lactantes, EISL), an observational cross-sectional multicentre study conducted in countries of Europe and Latin America.12

In the region of Pamplona, this study was conducted between 2006 and 2008, where 20 primary care centres participated. The population of the study were the infants of the metropolitan area of Pamplona (an urban area consisting of Pamplona and adjacent cities) who went to a health check-up at 15 months of age. The sample size was 3284 infants (from urban localities), all the children in the age range (12–15 months of age). Random sampling was not carried out, the questionnaire was given to all families, who were asked to complete it and return after completion. The study was approved by the Management of Primary Care of Navarre's Health Service and the Scientific Ethic Committee of University of Murcia.

Data collectionPaediatric nurses of the primary health centres explained the study to the families, and if they agreed to participate, after signing a full-informed written consent, a questionnaire and the instructions to complete it were given. Families filled out the questionnaire and could hand it in at the same primary health centre on the following visit, or send it to the Public University of Navarre by mail.

The questionnaire consisted of 74 questions about the infant (respiratory symptoms, feeding), his/her family (habits, diseases), environmental factors and pregnancy. No personal data were collected. This questionnaire has been previously validated.13 A Spanish version of the questionnaire was back translated to Basque (an official regional language) by the Department of Euskera of the Public University of Navarre, and both models were available.

Wheeze ever was defined as a positive answer to the question “Has your child wheeze in the first 12 months of his/her life?” Recurrent wheeze was defined as three or more episodes of wheezing in the first year of life.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was carried out. Chi Square and Student's-t test (as appropriate), with a statistical significance set at α<0.05, were performed in a univariate analysis to study the associations between the presence of wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing and factors, and the odds ratios (OR) with a confidence interval of 95% (95% CI) were calculated.

Non-conditional logistic regression analysis to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) by sex and age was used in those factors with p<0.1. Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS version 20 (Armonk, NY, USA).

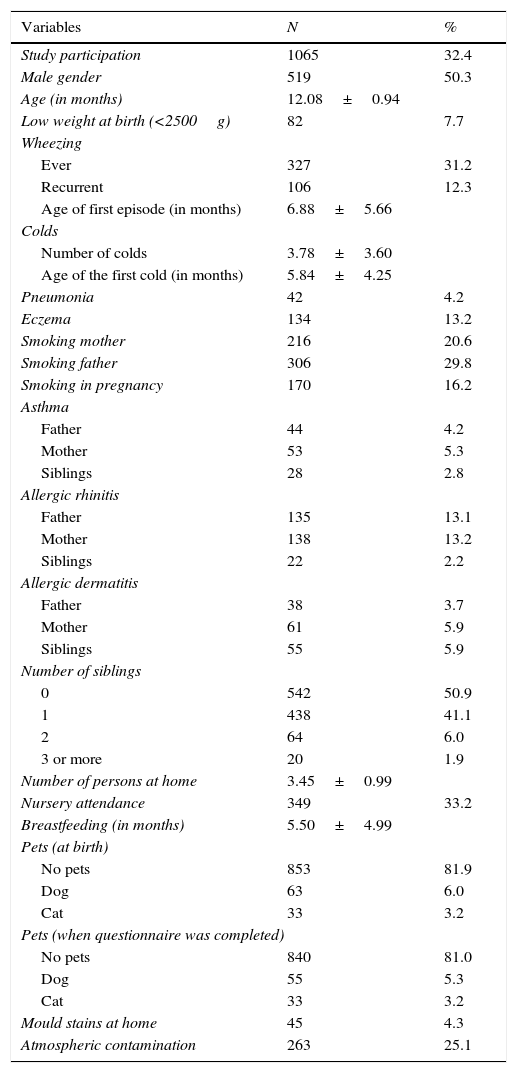

ResultsA total of 1065 questionnaires were answered, which meant a participation rate of 32.4%. Results from the descriptive analysis are shown in Table 1. Prevalence of wheezing in the first year was 31.2% (327), and 12.3% (106) were recurrent wheezers. Most of the questionnaires were completed by the mothers (79.9%) or both parents (15.8%), and almost all the infants were Caucasian and had been born in Spain (96.8% and 99.5%, respectively). 121 (13.1%) infants had attended the Emergency Department due to the severity of wheezing, and 27 (2.7%) had been hospitalised once and three (0.3%) twice for this cause.

Results from the descriptive analysis.

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Study participation | 1065 | 32.4 |

| Male gender | 519 | 50.3 |

| Age (in months) | 12.08±0.94 | |

| Low weight at birth (<2500g) | 82 | 7.7 |

| Wheezing | ||

| Ever | 327 | 31.2 |

| Recurrent | 106 | 12.3 |

| Age of first episode (in months) | 6.88±5.66 | |

| Colds | ||

| Number of colds | 3.78±3.60 | |

| Age of the first cold (in months) | 5.84±4.25 | |

| Pneumonia | 42 | 4.2 |

| Eczema | 134 | 13.2 |

| Smoking mother | 216 | 20.6 |

| Smoking father | 306 | 29.8 |

| Smoking in pregnancy | 170 | 16.2 |

| Asthma | ||

| Father | 44 | 4.2 |

| Mother | 53 | 5.3 |

| Siblings | 28 | 2.8 |

| Allergic rhinitis | ||

| Father | 135 | 13.1 |

| Mother | 138 | 13.2 |

| Siblings | 22 | 2.2 |

| Allergic dermatitis | ||

| Father | 38 | 3.7 |

| Mother | 61 | 5.9 |

| Siblings | 55 | 5.9 |

| Number of siblings | ||

| 0 | 542 | 50.9 |

| 1 | 438 | 41.1 |

| 2 | 64 | 6.0 |

| 3 or more | 20 | 1.9 |

| Number of persons at home | 3.45±0.99 | |

| Nursery attendance | 349 | 33.2 |

| Breastfeeding (in months) | 5.50±4.99 | |

| Pets (at birth) | ||

| No pets | 853 | 81.9 |

| Dog | 63 | 6.0 |

| Cat | 33 | 3.2 |

| Pets (when questionnaire was completed) | ||

| No pets | 840 | 81.0 |

| Dog | 55 | 5.3 |

| Cat | 33 | 3.2 |

| Mould stains at home | 45 | 4.3 |

| Atmospheric contamination | 263 | 25.1 |

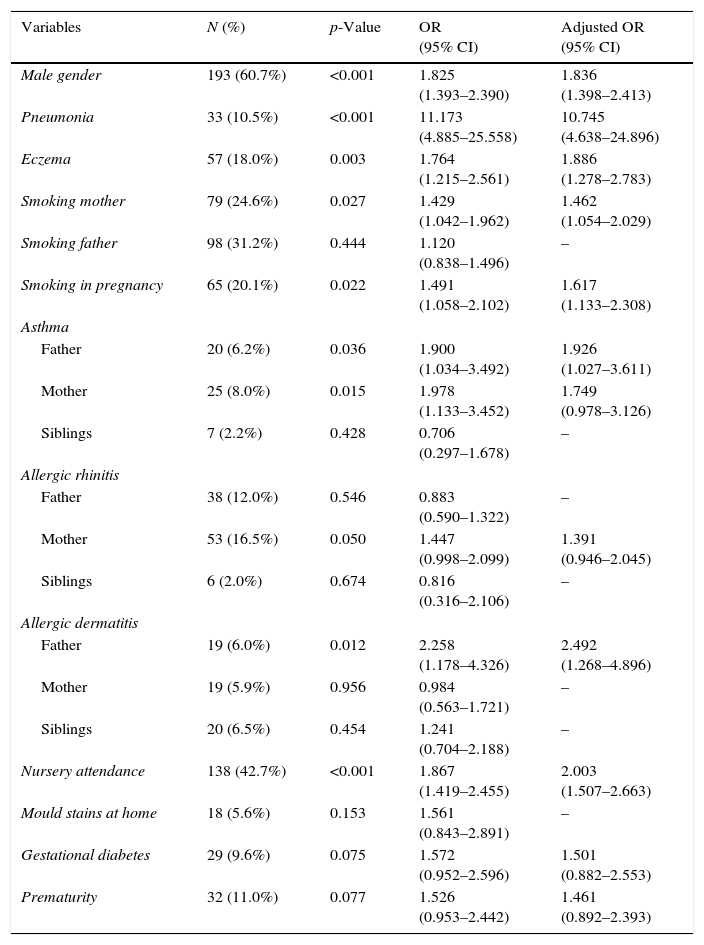

Risk factors for wheezing ever are shown in Table 2. A history of pneumonia, paternal allergic dermatitis and nursery attendance presented the largest OR. There were also associations between wheezing ever and a higher number of colds (p=<0.001; aOR 1.164, 95% CI 1.102–1.230) and number of persons at home (p=0.037; aOR 1.155, 95% CI 1.008–1.323).

Risk factors for wheezing ever in the first year of life.

| Variables | N (%) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 193 (60.7%) | <0.001 | 1.825 (1.393–2.390) | 1.836 (1.398–2.413) |

| Pneumonia | 33 (10.5%) | <0.001 | 11.173 (4.885–25.558) | 10.745 (4.638–24.896) |

| Eczema | 57 (18.0%) | 0.003 | 1.764 (1.215–2.561) | 1.886 (1.278–2.783) |

| Smoking mother | 79 (24.6%) | 0.027 | 1.429 (1.042–1.962) | 1.462 (1.054–2.029) |

| Smoking father | 98 (31.2%) | 0.444 | 1.120 (0.838–1.496) | – |

| Smoking in pregnancy | 65 (20.1%) | 0.022 | 1.491 (1.058–2.102) | 1.617 (1.133–2.308) |

| Asthma | ||||

| Father | 20 (6.2%) | 0.036 | 1.900 (1.034–3.492) | 1.926 (1.027–3.611) |

| Mother | 25 (8.0%) | 0.015 | 1.978 (1.133–3.452) | 1.749 (0.978–3.126) |

| Siblings | 7 (2.2%) | 0.428 | 0.706 (0.297–1.678) | – |

| Allergic rhinitis | ||||

| Father | 38 (12.0%) | 0.546 | 0.883 (0.590–1.322) | – |

| Mother | 53 (16.5%) | 0.050 | 1.447 (0.998–2.099) | 1.391 (0.946–2.045) |

| Siblings | 6 (2.0%) | 0.674 | 0.816 (0.316–2.106) | – |

| Allergic dermatitis | ||||

| Father | 19 (6.0%) | 0.012 | 2.258 (1.178–4.326) | 2.492 (1.268–4.896) |

| Mother | 19 (5.9%) | 0.956 | 0.984 (0.563–1.721) | – |

| Siblings | 20 (6.5%) | 0.454 | 1.241 (0.704–2.188) | – |

| Nursery attendance | 138 (42.7%) | <0.001 | 1.867 (1.419–2.455) | 2.003 (1.507–2.663) |

| Mould stains at home | 18 (5.6%) | 0.153 | 1.561 (0.843–2.891) | – |

| Gestational diabetes | 29 (9.6%) | 0.075 | 1.572 (0.952–2.596) | 1.501 (0.882–2.553) |

| Prematurity | 32 (11.0%) | 0.077 | 1.526 (0.953–2.442) | 1.461 (0.892–2.393) |

No associations were found with low weight at birth (p=0.268), pets, nor at birth or when the questionnaire was answered (p=0.810 and p=0.372, respectively), mould stains in the house (p=0.153), or breastfeeding fewer than six months (p=0.116).

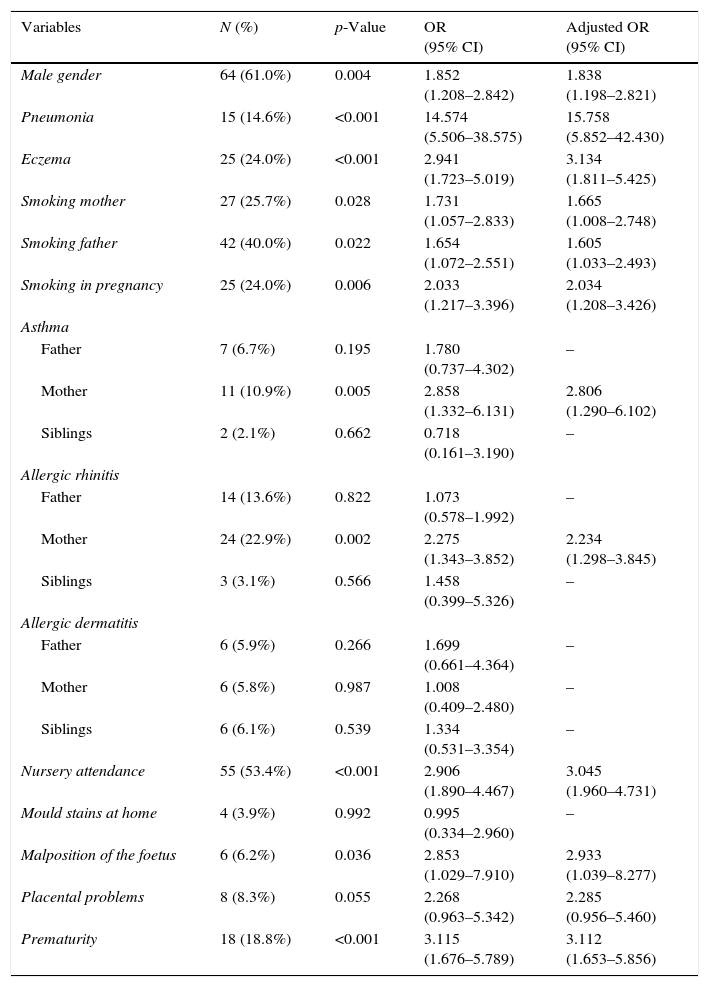

In Table 3, risk factors for recurrent wheezing are presented. A history or pneumonia, infant eczema, nursery attendance and prematurity at birth were the most important risk factors. Higher number of colds (p=<0.001; aOR 1.381, 95% CI 1.266–1.505) and higher number of smokers at home (p=0.029; aOR 1.328; 95% CI 1.017–1.735) were also risk factors for recurrent wheezing. There were no associations with low weight at birth (p=0.158), mould stains (p=0.992), atmospheric contamination (p=0.708) or breastfeeding fewer than six months (p=0.851).

Risk factors for recurrent wheezing in the first year of life.

| Variables | N (%) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 64 (61.0%) | 0.004 | 1.852 (1.208–2.842) | 1.838 (1.198–2.821) |

| Pneumonia | 15 (14.6%) | <0.001 | 14.574 (5.506–38.575) | 15.758 (5.852–42.430) |

| Eczema | 25 (24.0%) | <0.001 | 2.941 (1.723–5.019) | 3.134 (1.811–5.425) |

| Smoking mother | 27 (25.7%) | 0.028 | 1.731 (1.057–2.833) | 1.665 (1.008–2.748) |

| Smoking father | 42 (40.0%) | 0.022 | 1.654 (1.072–2.551) | 1.605 (1.033–2.493) |

| Smoking in pregnancy | 25 (24.0%) | 0.006 | 2.033 (1.217–3.396) | 2.034 (1.208–3.426) |

| Asthma | ||||

| Father | 7 (6.7%) | 0.195 | 1.780 (0.737–4.302) | – |

| Mother | 11 (10.9%) | 0.005 | 2.858 (1.332–6.131) | 2.806 (1.290–6.102) |

| Siblings | 2 (2.1%) | 0.662 | 0.718 (0.161–3.190) | – |

| Allergic rhinitis | ||||

| Father | 14 (13.6%) | 0.822 | 1.073 (0.578–1.992) | – |

| Mother | 24 (22.9%) | 0.002 | 2.275 (1.343–3.852) | 2.234 (1.298–3.845) |

| Siblings | 3 (3.1%) | 0.566 | 1.458 (0.399–5.326) | – |

| Allergic dermatitis | ||||

| Father | 6 (5.9%) | 0.266 | 1.699 (0.661–4.364) | – |

| Mother | 6 (5.8%) | 0.987 | 1.008 (0.409–2.480) | – |

| Siblings | 6 (6.1%) | 0.539 | 1.334 (0.531–3.354) | – |

| Nursery attendance | 55 (53.4%) | <0.001 | 2.906 (1.890–4.467) | 3.045 (1.960–4.731) |

| Mould stains at home | 4 (3.9%) | 0.992 | 0.995 (0.334–2.960) | – |

| Malposition of the foetus | 6 (6.2%) | 0.036 | 2.853 (1.029–7.910) | 2.933 (1.039–8.277) |

| Placental problems | 8 (8.3%) | 0.055 | 2.268 (0.963–5.342) | 2.285 (0.956–5.460) |

| Prematurity | 18 (18.8%) | <0.001 | 3.115 (1.676–5.789) | 3.112 (1.653–5.856) |

Wheezing in infants is a major problem, affecting not only the quality of life of infants, but also of their families. Our study has found several risk factors related to wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing in infants from the region of Pamplona.

Prevalence of wheezing ever in infants in our study was 31.2%, a similar prevalence compared to other EISL studies conducted in Spain, in the city of Salamanca, which found 32.3%14 and in Netherlands, 28.5%,7 but less prevalence than in Latin America countries, where mean prevalence was 47.3%.15 Prevalence of recurrent wheezing was 12.3%, similar to the other Spanish EISL study,14 but lower than other European and Latin American studies.7,9

Male gender was a risk factor for wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing in our study. This finding is in accordance with what has been found in other studies,16,17 suggesting a genetic role in the appearance of wheezing.

In our study, low birth weight did not show any association with wheezing ever or recurrent wheezing. Our results contrast with findings from another Brazilian study in which low birth was an independent risk factor for occasional wheezing.18

Both a history of pneumonia and a higher number of colds were risk factors for wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing. Several studies agree with these findings,19,20 with pneumonia being a strong risk factor for recurrent wheezing in European and Latin American countries.21 The relevance of infections of the respiratory tract has been previously studied, describing the relation between viral infections22 and the development of wheezing.

In our study, infant eczema presented a higher risk for both wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing. This relation was also found in another EISL study,14 although it is not a general finding, suggesting it affects some populations. Garcia-Marcos et al.21 found that infant eczema was a risk factor for pneumonia in infants, which suggests a role between eczema and the development of other risk factors which lead to wheezing.

We found that smoking mother, as well as smoking during pregnancy, were risk factors for wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing, findings which have been previously described in many studies.23–25 Although a Spanish study found that paternal smoking was not associated with wheezing,26 we found it as risk factor for recurrent wheezing. Our results also show that number of smokers at home was a risk factor for recurrent wheezing, according to the finding that household smoking increases the risk of wheeze.24 Exposure to smoke, especially during pregnancy, is related to decreased lung function in children,27 suggesting an important influence in the apparition of the disease.

As in our study, a parental history of asthma has been found as risk factors in many studies.9,15 These results may suggest the existence of a hereditary mechanism for asthma and wheezing.28 Maternal allergic rhinitis was found as a risk factor for recurrent wheezing, and paternal allergic dermatitis for wheezing ever. These results agree with results from others EISL studies,7,9 where allergic diseases were risk factors for wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing.

Attending nursery school was found as a risk factor for both wheezing ever and recurrent wheezing. Previous results are conflictive, with several studies which either not found any association,29 or described a protective effect,30 while others agree with our results.31 An explanation for our results may be that children who attended a nursery school were in contact with other children and a different environment, increasing the exposure to possible risk factors.

We did not find any relation between mould stains in the house and wheezing ever or recurrent wheezing, contrary to the Dutch EISL study,7 which found damp housing as a strong risk factor in both cases. In our study, only a few families reported mould stains or damp at home, which may have affected our findings, causing an underestimation of its influence.

Complications during pregnancy, specifically prematurity and malposition of the foetus, were risk factors for recurrent wheezing. Both, prematurity32 and malpresentation of the foetus33 were previously found associated with recurrent wheezing and asthma. Premature infants are born with abnormalities in their airways, which probably provoke the apparition of wheezing.34 In the same way, malposition is supposed to affect the lung function of the foetus, which can cause respiratory problems at an early age.

Breastfeeding showed no association in our study. Findings from previous studies are conflictive. Breastfeeding was found as a protective factor in some of them.10 However, other studies did not reach any relationship,35 or even described breastfeeding as a risk factor for asthma in childhood.36

Although previous studies have described a protective effect in those children with pets in the house,37 probably due to the exposition at early age to certain microorganisms that confer protection against asthma, findings are conflictive.38 Our results did not show any association between the presence of pets at home and wheezing ever or recurrent wheezing.

We did not find any relation with air pollution in our study. However, several studies have found associations between this factor and wheezing.39,40 The questionnaire asked for a personal perception of air pollution level, which means a subjective measure that may have led to underestimation.

One of the strengths of this study was the use of a validated questionnaire, a well-recognised tool which has been used in other studies. Moreover, this study is part of the multicentre EISL project, which enables the comparison of the results obtained with other centres from Spain or other countries. One of the limitations of the study is its cross-sectional design, although the main weakness is its low participation, probably due to the low participation of the immigrant population, and to data protection issues and authorisations of the Health System, which made it not possible to send reminder letters or telephone calls to participants, which would have increased the participation, reducing the confusion of some results, or allows finding others.

In conclusion, wheezing in infants is a common disease, with several identified risk factors, like pneumonia, family history of asthma and nursery attendance. Further studies are needed to test if these findings are consistent, and intervention against the preventable factors should be addressed.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animals subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Sources of supportResearch grant from Carlos III Institute, Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs Ref, PI 050918; research grant from the Department of Health, Government of Navarra, Spain, Ref 6106.

Conflict of interestNo author has any conflict of interest to declare.

This study has been funded by two Research Grants from Carlos III Institute, Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs Ref, PI 050918, and from the Department of Health, Government of Navarra, Spain, Ref 6106.