Prostate cancer is the tumor with the highest incidence in Spanish men. The implementation of health literacy and therapeutic education programs adapted to the needs of the population could be a resource to minimize the sequelae derived from the treatments used to combat this pathology. To this end, it would be necessary to know the level of health literacy about prostate cancer.

ObjectiveTo determine the level of health literacy in prostate cancer in the Spanish male population using the validated version of the PCKQ-12 for the Spanish population.

MethodologyCross-sectional, population-based, descriptive study. Spanish-speaking men of legal age were included. To carry out the study, an ad hoc questionnaire was designed on the Google Forms platform, which was distributed via WhatsApp. Previously, it was necessary to validate the PCKQ-12 to the Spanish population in two phases, a first phase for translation and cross-cultural adaptation and a second phase to test the measurement properties.

ResultsThe Spanish version of the PCKQ-12 showed good language, conceptual, semantic and content equivalence and could be used to assess health literacy in prostate cancer. Three hundred and seventy Spanish men with a mean age of 43.87 (SD 13.65) years responded to the questionnaire. The level of prostate cancer health literacy found was low (6.72 points), being 2 points higher in health men.

ConclusionHealth literacy about prostate cancer in the Spanish male population is low.

El cáncer de próstata es el tumor de mayor incidencia en varones españoles. La implantación de programas de alfabetización en salud y educación terapéutica adaptados a las necesidades poblacionales podría ser un recurso para minimizar las secuelas derivadas de los tratamientos que combaten esta patología. Para ello, sería necesario conocer el nivel de alfabetización en salud sobre el cáncer de próstata.

ObjetivoConocer el nivel de alfabetización en salud en cáncer de próstata en población masculina española mediante la versión validada a la población española del PCKQ-12.

MetodologíaEstudio descriptivo transversal, de base poblacional. Se incluyeron varones hispanohablantes mayores de edad. Para llevar a cabo el estudio, se diseñó un cuestionario ad hoc en la plataforma de Google Forms, que se difundió mediante WhatsApp. Previamente fue necesario validar a la población española el PCKQ-12 en dos fases, una primera para la traducción y adaptación transcultural y una segunda para la comprobación de las propiedades de medición.

ResultadosLa versión española del PCKQ-12 mostró una buena equivalencia idiomática, conceptual, semántica y de contenido pudiéndose utilizar para conocer la alfabetización en salud en cáncer de próstata. Trescientos setenta hombres españoles con una media de edad de 43,87 (DE 13,65) años respondieron al cuestionario. El nivel de alfabetización en salud sobre cáncer de próstata hallado fue bajo (6,72 puntos), siendo 2 puntos superiores en aquellos varones sanitarios.

ConclusiónLa alfabetización en salud sobre el cáncer de próstata en la población masculina española es baja.

According to the Global Cancer Observatory, prostate cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide with 1.4 million new diagnoses.1 These figures may be partly due to the implementation of screening tests in asymptomatic patients.2,3

The prevalence in Spain in 2020 was 259,788 cases.4 Fortunately, mortality rates for prostate cancer are decreasing, but the number of survivors living with the sequelae generated by medical-surgical treatments is increasing.5,6 The most prevalent and significant sequelae are pelvic floor dysfunctions such as urinary incontinence (UI), present in 2–60%7 and sexual dysfunctions, specifically erectile dysfunction (ED), which affects between 10 and 46%8 of prostate cancer survivors. These dysfunctions, together with the social, physical and emotional changes that subjects may experience after prostate cancer treatments, affect their quality of life (QoL) to a greater or lesser extent, depending on their age, comorbidities, knowledge of their pathology and stage of the disease.9

Due to the heterogeneity of guidelines on the use of screening tests and the information provided by healthcare professionals and the Internet, informed and shared decision making is becoming increasingly important. In order for patients and their families to make the most appropriate decision for their situation, they must be aware of the risks and benefits associated with this type of tests and of those that would follow a possible diagnosis.10 This situation is directly related to the level of education of each subject, since the lower the level of education, the lower the understanding and correct interpretation of health information.11 Therefore, the improvement of health literacy, defined by the WHO in 1998 and updated by Liu et al.12 as “the ability of an individual to obtain and translate knowledge and information to maintain and improve health in a way that is appropriate to the individual and system contexts”, could enhance the active role implemented by the current biopsychosocial model.13

Health literacy is a recognized determinant of population health outcomes; however, it remains an understudied and, in the case of men, under-researched area. In fact, several authors have suggested a gender bias in favor of women in health literacy research and, specifically, in pelvic health research.14,15 Lower health literacy is associated with greater difficulty understanding and processing cancer-related information, poorer quality of life, and poorer experience of care.16 Health literacy affects men's health practices and self-management of prostate cancer.17 Better knowledge and understanding of men's health literacy levels about prostate cancer is necessary for the development of tailored programs for the management and monitoring of prostate cancer treatment sequelae such as UI and sexual dysfunction.

Current literature does not provide information on the specific level of health literacy about prostate cancer in the Spanish male population. The aim of this study is to determine the level of health literacy in prostate cancer in the Spanish male population.

MethodologyTo determine the level of prostate cancer knowledge in the Spanish male population, we needed to validate the PCKQ-12 in the Spanish male population. The original 40-item English version was adapted and shortened by Rees et al.18 in 2003 to measure prostate cancer knowledge. It is a 12-item self-report questionnaire that assesses knowledge of prostate cancer diagnosis (items 9–12), symptoms (items 2 and 4), risk factors (items 1 and 3), treatment side effects (items 6–8), and screening age guidelines (item 5). The response options are true, false, or don't know. The correct answer is true for 8 of the items1,2,4–7,11,12 and false for the remaining 4 items.3,8–10 Higher scores indicate more knowledge about prostate cancer. Since the development of the questionnaire, it has been used in several studies to determine the level of prostate cancer knowledge in Iranian, Saudi, American, and Jordanian populations, among others.19–23

Validation of the Prostate Cancer Knowledge 12 (PCKQ-12) Questionnaire in the Spanish PopulationTo validate the PCKQ-12 questionnaire, a descriptive, cross-sectional, population-based study was designed and conducted between March 2021 and July 2022 within the Physiotherapy in Women's Health Processes (FPSM) research group. It was approved by the Animal Research and Experimentation Ethics Committee of the University of Alcalá (CEID/HU/2019/34).

There were two phases. The first involved the translation, back-translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire, and the second involved the analysis of its comprehensibility and measurement properties. The study included Spanish-speaking men, aged 18 years and older, with and without prostate cancer, who confirmed their participation and gave their informed consent after being informed about the study. They were recruited using exponential discriminative snowball sampling (Fig. 1) and the questionnaire, created ad hoc on the Google Forms platform, was distributed via email and WhatsApp. In addition to being the Spanish version of the PCKQ-12, this questionnaire included sociodemographic data and several questions related to prostate pathology (Supplementary material A).

We followed the phases proposed and standardized by the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Working Group of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR).24 After undergoing translation and cross-cultural adaptation, the comprehensibility and psychometric properties of the new version, specifically construct validity, structural validity, test-retest reliability, responsiveness, interpretability, and feasibility, were assessed according to the recommendations of the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN).25

The detailed methodology of the validation of the PCKQ-12 in the Spanish population and its results, as well as the Spanish version of the PCKQ-12 itself, are described in detail in Supplementary material B.

Health literacy in prostate cancer in the Spanish male populationTo determine the level of health literacy in prostate cancer, we used the validated version of the PCKQ-12 for the Spanish population in a descriptive, cross-sectional, population-based study conducted between September 2022 and June 2023. All procedures in the study were performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave their informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of [MASKED].

ParticipantsParticipants were recruited using exponential non-discriminative snowball sampling. They received a WhatsApp message containing a descriptive introduction to the study, the informed consent form, and the PCKQ-12 questionnaire validated for the Spanish population. This message was distributed among the known contacts of the researchers, who distributed the message to their contacts.

Inclusion criteria were men of legal age, whose mother tongue was Spanish and who lived in Spain. Those who suffered from any visual or cognitive impairment that prevented them from understanding and completing the questionnaire were excluded.

ProcedureAn ad hoc questionnaire was designed on the Google Forms platform (Supplementary material C). The questionnaire was administered through this platform. This allowed access with any electronic device with an Internet connection. The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) was followed.26

The data collection period for the questionnaire to learn about prostate cancer health literacy in the Spanish male population was 2 months.

Sample sizeThe sample size was calculated a priori for infinite samples based on the prevalence of UTI after prostatectomy of 25% in Spain according to Escobar et al.27 A 95% confidence interval (CI) and a maximum allowed estimation error of 0.05 were considered.

Statistical methodsAfter assessing the normality of variables using the Shapiro-Wilk test, categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies, and quantitative variables are presented as median and interquartile range or mean and standard deviation (SD). A 95% CI was estimated, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for inductive or inferential analysis. To calculate the association of the score with sociodemographic variables, Spearman's correlation was used for quantitative variables and Mann–Whitney U tests (dichotomous variables) or Kruskal–Wallis (polytomous) for qualitative variables.

All data were analyzed using SPSS (version 29.0, IBM, Chicago, USA) for Windows by a masked statistician who received the coded data.

ResultsValidation and measurement of the psychometric properties of the PCKQ-12The translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the PCKQ-12 demonstrated adequate content, semantic, and conceptual equivalence.

The total sample consisted of 269 men. It was divided into an experimental group (n&#¿;=&#¿;181), consisting of men with and without prostate cancer, and a control group (CG), consisting of health professionals and health science students (n&#¿;=&#¿;81). There were no losses in subjects' responses, nor were there any ceiling or floor effects on any item after the final version of the questionnaire was completed by the groups.

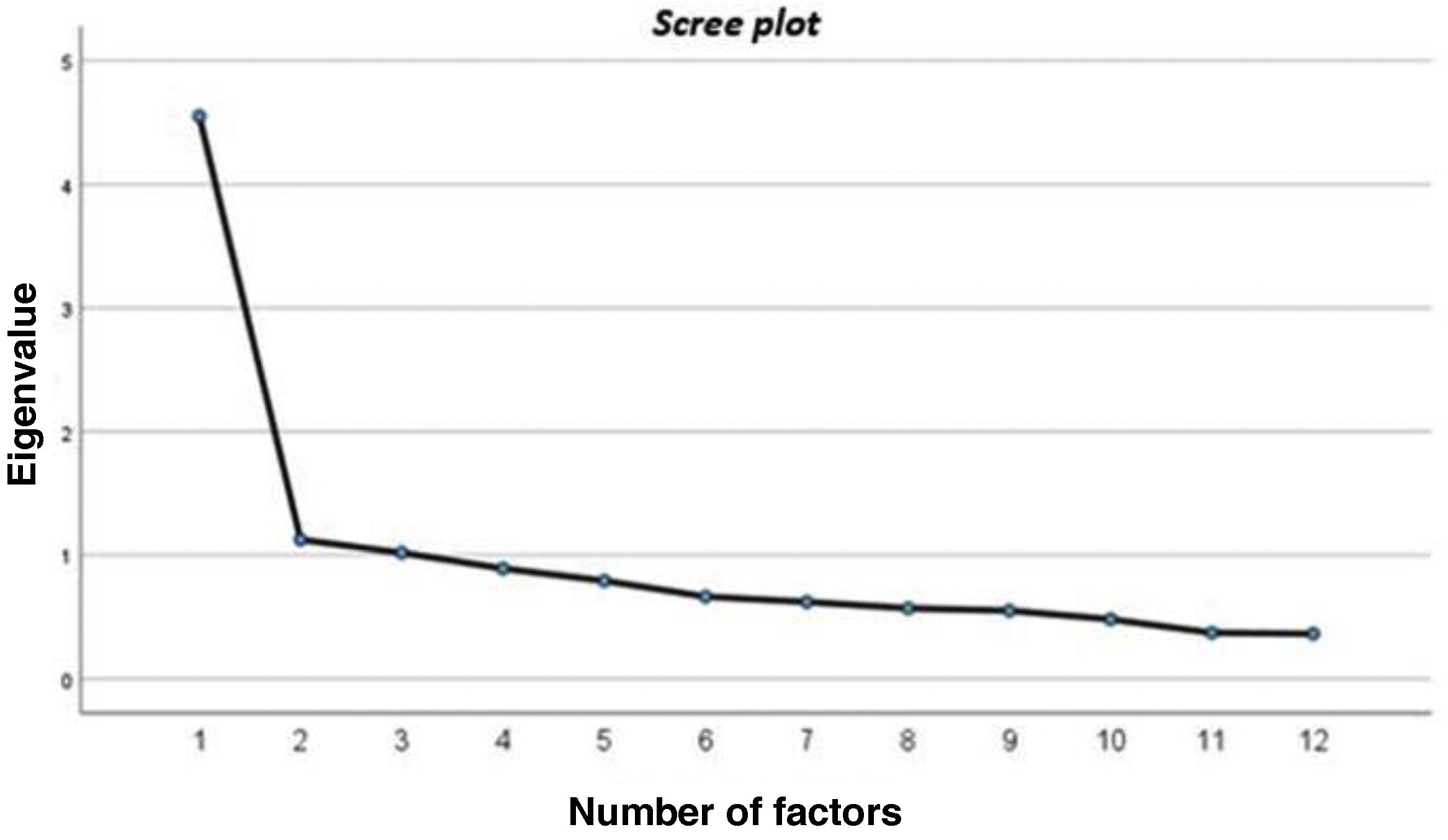

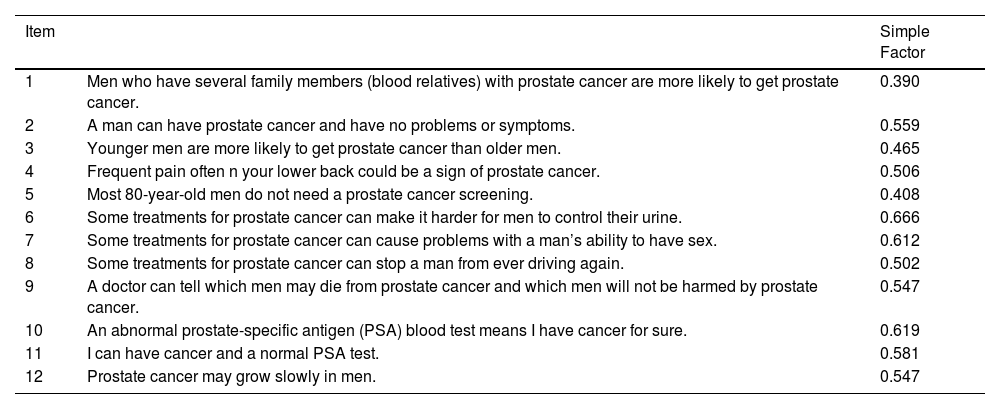

The scree plot (Fig. 2) and the factor loadings (Table 1) suggest that the one-factor solution proposed in the original version is maintained. Only item 1 showed a loading <0.4, but we decided to keep it based on the content and the original version. This factor structure explained 33.94% of the variance. The construct validity confirmed the hypothesis regarding score differences between groups (p&#¿;<&#¿;0.001). The CG obtained the best scores with a large effect size (r&#¿;=&#¿;0.74).

Factor loadings for one-factor solution (n&#¿;=&#¿;188).

| Item | Simple Factor | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Men who have several family members (blood relatives) with prostate cancer are more likely to get prostate cancer. | 0.390 |

| 2 | A man can have prostate cancer and have no problems or symptoms. | 0.559 |

| 3 | Younger men are more likely to get prostate cancer than older men. | 0.465 |

| 4 | Frequent pain often n your lower back could be a sign of prostate cancer. | 0.506 |

| 5 | Most 80-year-old men do not need a prostate cancer screening. | 0.408 |

| 6 | Some treatments for prostate cancer can make it harder for men to control their urine. | 0.666 |

| 7 | Some treatments for prostate cancer can cause problems with a man’s ability to have sex. | 0.612 |

| 8 | Some treatments for prostate cancer can stop a man from ever driving again. | 0.502 |

| 9 | A doctor can tell which men may die from prostate cancer and which men will not be harmed by prostate cancer. | 0.547 |

| 10 | An abnormal prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test means I have cancer for sure. | 0.619 |

| 11 | I can have cancer and a normal PSA test. | 0.581 |

| 12 | Prostate cancer may grow slowly in men. | 0.547 |

A high internal consistency was found, with a Cronbach's Alpha&#¿;=&#¿;0.81 ((95% CI (0.76–85)). The questionnaire score distribution scores and test-retest reliability presented congruent results, both of which are detailed in Supplementary material B.

Finally, the results corresponding to responsiveness confirmed a large effect size (r&#¿;=&#¿;1.46) on the constructs measured by the PCKQ-12.

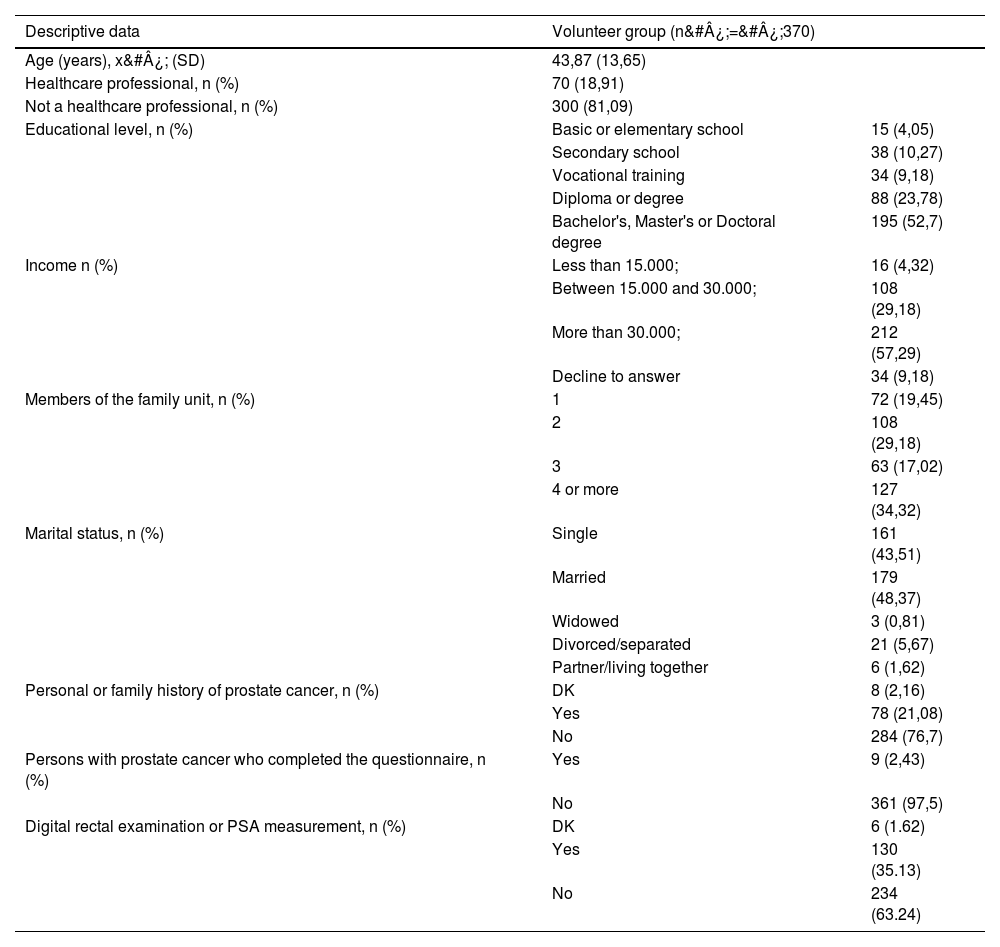

Health literacy in prostate cancerThe total sample included 370 participants ranging in age from 20 to 78 years. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the participants.

Characteristics of participants in prostate cancer literacy program.

| Descriptive data | Volunteer group (n&#¿;=&#¿;370) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), x&#¿; (SD) | 43,87 (13,65) | |

| Healthcare professional, n (%) | 70 (18,91) | |

| Not a healthcare professional, n (%) | 300 (81,09) | |

| Educational level, n (%) | Basic or elementary school | 15 (4,05) |

| Secondary school | 38 (10,27) | |

| Vocational training | 34 (9,18) | |

| Diploma or degree | 88 (23,78) | |

| Bachelor's, Master's or Doctoral degree | 195 (52,7) | |

| Income n (%) | Less than 15.000; | 16 (4,32) |

| Between 15.000 and 30.000; | 108 (29,18) | |

| More than 30.000; | 212 (57,29) | |

| Decline to answer | 34 (9,18) | |

| Members of the family unit, n (%) | 1 | 72 (19,45) |

| 2 | 108 (29,18) | |

| 3 | 63 (17,02) | |

| 4 or more | 127 (34,32) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | Single | 161 (43,51) |

| Married | 179 (48,37) | |

| Widowed | 3 (0,81) | |

| Divorced/separated | 21 (5,67) | |

| Partner/living together | 6 (1,62) | |

| Personal or family history of prostate cancer, n (%) | DK | 8 (2,16) |

| Yes | 78 (21,08) | |

| No | 284 (76,7) | |

| Persons with prostate cancer who completed the questionnaire, n (%) | Yes | 9 (2,43) |

| No | 361 (97,5) | |

| Digital rectal examination or PSA measurement, n (%) | DK | 6 (1.62) |

| Yes | 130 (35.13) | |

| No | 234 (63.24) | |

x&#¿;: mean; SD: standard deviation; n: number; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; DK: don’t know.

The analysis of the results obtained after completion of the ad hoc questionnaire that included the PCKQ-12 yielded a total mean score of 6.72 (2.72). Their scores ranged from 0 to 12 with a median score of 7.

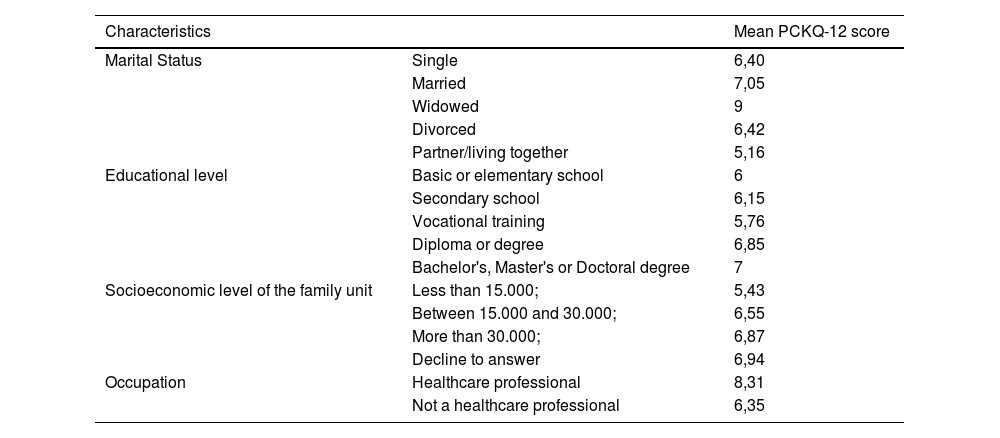

The mean score obtained in relation to knowledge about prostate cancer according to marital status, level of education, profession, and income is shown in Table 3.

Mean score according to sociodemographic characteristics.

| Characteristics | Mean PCKQ-12 score | |

|---|---|---|

| Marital Status | Single | 6,40 |

| Married | 7,05 | |

| Widowed | 9 | |

| Divorced | 6,42 | |

| Partner/living together | 5,16 | |

| Educational level | Basic or elementary school | 6 |

| Secondary school | 6,15 | |

| Vocational training | 5,76 | |

| Diploma or degree | 6,85 | |

| Bachelor's, Master's or Doctoral degree | 7 | |

| Socioeconomic level of the family unit | Less than 15.000; | 5,43 |

| Between 15.000 and 30.000; | 6,55 | |

| More than 30.000; | 6,87 | |

| Decline to answer | 6,94 | |

| Occupation | Healthcare professional | 8,31 |

| Not a healthcare professional | 6,35 | |

CI: confidence interval; PCKQ-12: Prostate Cancer Knowledge Questionnaire.

The level of knowledge about prostate cancer presented by the subjects diagnosed with this disease versus those without the disease was 8.22 versus 6.68 points on average, respectively. Men who had previously undergone a screening test for prostate pathology obtained a higher score than those who had not, 7.35 versus 6.37 points, respectively. We also analyzed the number of correct and incorrect responses for each item of the PCKQ-12, concluding that the questions with the lowest number of correct responses were those related to symptoms, screening guidelines and diagnosis (items 4, 5 and 11).

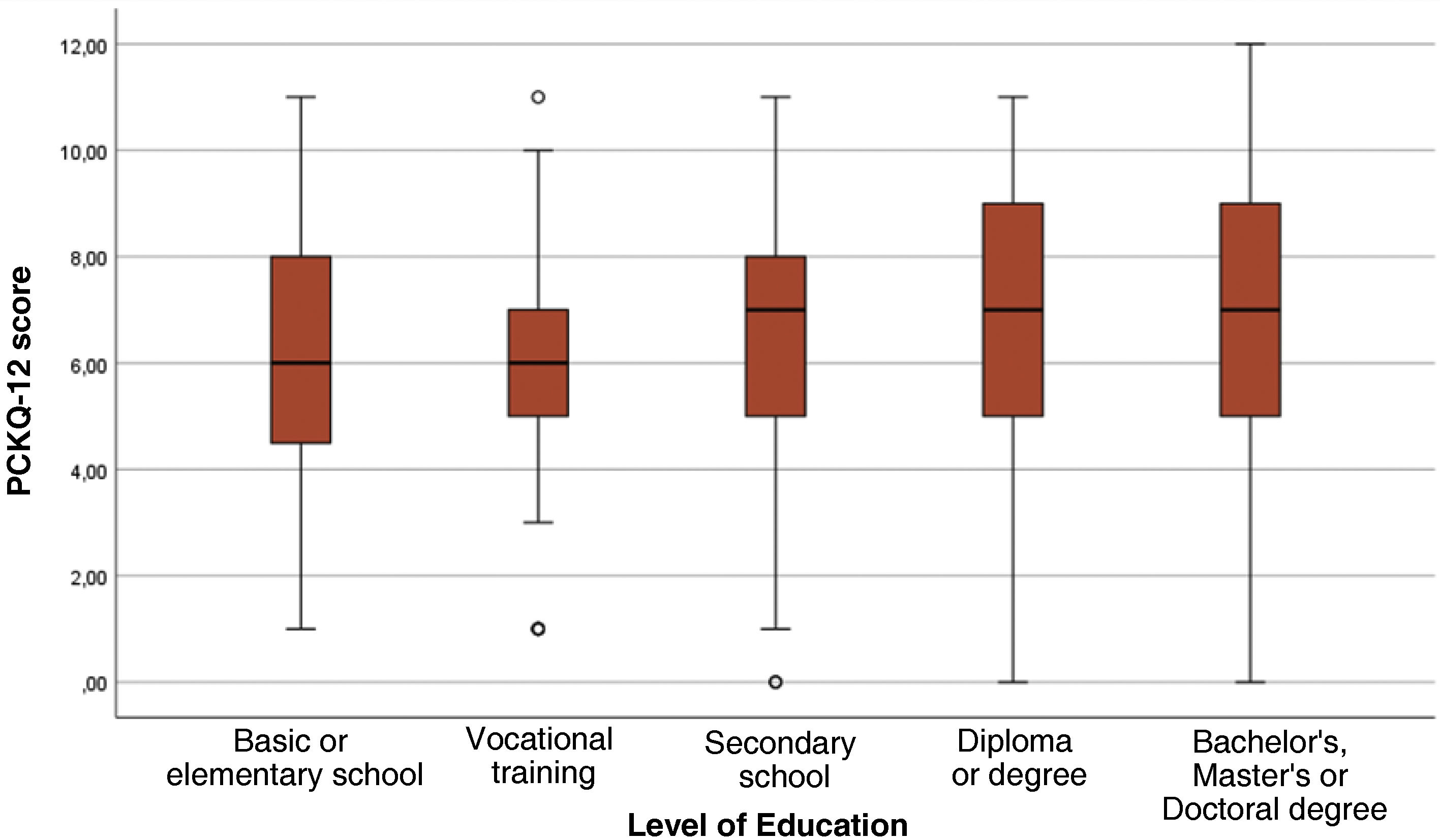

The score was statistically higher in those patients with health education (p&#¿;<&#¿;0.001) and was statistically different (p&#¿;=&#¿;0.038) according to educational level (Fig. 3), but not according to income level (p&#¿;=&#¿;0.305). There was also statistical significance, but very low correlation between age and score (rho&#¿;=&#¿;0.113; p&#¿;=&#¿;0.030).

Box plot of the distribution of PCKQ-12 scores according to educational level.

The median, represented by a horizontal line inside the box, first and third quartiles (orange box) and outlier cases (points outside the extremes) are shown. Significant differences were found as a function of educational level (p&#¿;=&#¿;0.038).

The validated PCKQ-12 questionnaire was found to be an appropriate, feasible and comprehensible tool to assess the knowledge of Spanish men about prostate cancer. In addition, the final score can be obtained quickly, which is essential in research or daily clinical practice.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to assess the health literacy of Spanish men with prostate cancer. The completion of the Spanish version of the PCKQ-12 by Spanish men allowed us to determine the current level of health literacy in prostate cancer in the Spanish male population, with a mean score of 6.72. According to the author of the original short version,18 the interpretation of the result is that scores ≤7 correspond to a low level of knowledge, thus showing a deficient knowledge about prostate cancer in the sample studied.

Item 5, which is related to screening guidelines, received the lowest score. This supports the need for educational efforts targeted at the corresponding population (in this case, men with prostate cancer) to encourage and improve access to screening tests.22,23 The study by Jamieson et al.28 concludes that patients with high levels of health literacy are more likely to undergo PSA testing. In line with this statement, the present study showed that men who had previously undergone a screening test for prostate pathology had a better score (7.35) than those who had not (6,37).

When the results were analyzed according to the different sociodemographic characteristics of the subjects, the best data on prostate cancer education level were obtained by married men, which may be due to the influence of women on their spouse's health care decisions.29 In addition, men with higher levels of education (bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral degree) scored higher. This is consistent with previous research confirming that higher levels of education are associated with better health-related knowledge.22 Similarly, men with an annual household income of more than ;30,000 also scored higher, which is consistent with similar studies evaluating this characteristic and concluding that greater purchasing power is associated with greater health knowledge.30 The mean knowledge of subjects diagnosed with prostate cancer was almost two points higher than that of healthy subjects. This supports the idea that subjects with prostate cancer have a higher level of health literacy in prostate cancer than the general population. Previous studies19–21,23 that assessed the level of health literacy in the general population obtained results similar to or lower than those of the present study.

Currently, there are no health promotion and prevention programs related to prostate cancer at the state level. In pathologies such as breast cancer, these types of projects are carried out with a good reception and response. Therefore, according to the results obtained in the present study, it would be positive to implement these in primary care health centers through interactive educational programs of prevention to improve health literacy related to prostate cancer. Our proposal would be a preventive approach in healthy subjects younger than the average age of diagnosis of prostate cancer (<64 years). Through face-to-face group sessions reinforced with online sessions, information would be provided through videos, interactive games or mobile applications where the subject can interact and collect the proposed information. This would include content on the basic anatomy of the male perineum and its functions, the symptoms and signs of this urological pathology, information on diagnostic and screening tests for prostate cancer, medical and non-medical treatment for prostate cancer, its sequelae and treatment of these in prostate cancer survivors.

Strengths, limitations and future directionsThe main strength of this study is that it used a questionnaire validated specifically to determine health literacy in prostate cancer in the Spanish population. This questionnaire was cross-culturally adapted and validated for the Spanish male population. This allows us to compare the results with other projects carried out at international level and to generate an educational line with health literacy strategies adapted to the country of origin. Nevertheless, the study is not free of limitations, such as those inherent to a cross-sectional study, which make it impossible to infer causality. Also, due to the nature of the study, the results are subject to selection bias. It would be interesting if future studies included a higher percentage of men with a level of education closer to that of the general Spanish male population. Occupation has been shown to be a relevant factor in obtaining different results and should be considered in future research.

Implications for clinical practice and researchSince prostate cancer is the most common tumor in the Spanish male population, tailored prevention and health promotion programs can be a primary resource to minimize and improve the management of prostate cancer sequelae. Thanks to the PCKQ-12, a simple, quick and validated measurement tool for the Spanish male population, prostate cancer literacy can be determined in order to create health literacy programs on prostate cancer adapted to the real level of knowledge of the population on prostate cancer.

ConclusionsThe Spanish version of the PCKQ-12 questionnaire has proven to be a valid tool, with good internal consistency, obtaining positive values in its test-retest reliability, which allowed us to determine the level of health literacy about prostate cancer in the Spanish male population.

The level of health literacy in prostate cancer in the Spanish male population is low, raising the need for tailored educational programs to improve the understanding and self-management of prostate cancer.

Take-home messagesSince prostate cancer is the first most common tumor in the Spanish male population, tailored prevention and health promotion programs can be a resource to minimize and improve the management of prostate cancer sequelae.

The PCKQ-12 version validated for the Spanish male population has shown good idiomatic, conceptual, semantic and content equivalence for collecting data on health literacy in prostate cancer.

The validation of the PCKQ-12 questionnaire in the Spanish male population allows us to determine the level of health literacy in prostate cancer in order to adapt educational programs to the actual level of knowledge about prostate cancer.

Health literacy about prostate cancer in the general Spanish male population is low.

FundingThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the volunteers who participated in the study.