While the title may lead you to think that this paper is about spiders, it is about firms in the United States reporting relevant business information to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The paper is meant to serve as a primer for economists in the computing details of searching for information on the Internet. One important goal of the paper is to show how simple open-source computer scripts can be generated to access financial data on firms that interact with regulators in the United States.

Business relevant information is more easily available today than ever before. Information about corporations, investors, and security markets gets disseminated through the Internet almost instantaneously. For the most part, the available information is unstructured in the form of a text. It is easy to see that a strategy of trading on information acquired from free form text would become more profitable the faster you are able to read the text. Hence it is not surprising that text analytics is becoming increasingly important on Wall Street.1 Hoping to capture the current mood of investors, some traders are using computer programs to monitor and decode the words, opinions, rants and even keyboard-generated smiley faces posted on social networking sites.2 Academia has followed suit. Computerized decoding of “textual information” into quantitative metrics has become an important area of research in financial economics.

This paper is meant to be a teaser to researchers in financial economics that lowers the costs of entry into the field of text analytics. The paper develops, presents and explains a set of simple Perl programs that will allow access to the electronic filing system (EDGAR) used by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to disseminate business relevant information. To illustrate how to download and extract information from EDGAR, we use Form 8-K to analyze executive turnover (new hires and departures of corporate executives). We investigate if there is a calendar effect in executive turnover (there is). But the findings on this particular question are not the main point of this paper. Our key contribution is to show how easy it is to access and analyze the various forms that companies and investors file electronically with the SEC.

The empirical literature that uses textual data as their main data source is growing. García and Norli (in press), Phillips and Hoberg (2010), and Kogan et al. (2009) analyze the annual report filed by firms on Form 10-K. Another strand of the literature has focused on textual analysis of newspaper articles: Tetlock (2007) picks up investor sentiment by analyzing newspaper articles on the stock market, while Dougal et al. (2012) use exogenous scheduling of Wall Street Journal columnists to identify a causal relation between financial reporting and stock market performance. Engelberg (2008) analyze earnings announcements, Hoberg and Hanley (2012) study IPO prospectuses.3

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2 we present some details on the EDGAR filing system. The next section presents a few simple algorithms to extract basic information from 8-K statements filed with the SEC through EDGAR. Section 4 presents an analysis of the calendar effects around aggregate filings of 8-K statements that discuss executive turnover. The last section concludes.

2EDGARCompanies and others are required by law to file a number of different forms with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The main purpose of filing these forms is to make certain types of information available to investors and corporations – and by that improve the efficiency of security markets. Historically these forms have been filed with the SEC on paper. In the early 1990s the SEC developed the Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval (EDGAR) system to handle electronic form filing.4 As of May 6, 1996 all public U.S. companies were required to make all their filings, with a few exceptions, on EDGAR. More importantly, any person with access to a computer linked to the Internet can obtain and read these filings within seconds after they are filed.

As researchers looking for relevant information on companies with operations in the United States, we have traditionally relied on databases including Compustat, ExecuComp, SDC Platinum, etc. These databases are attractive because their owners have collected data from companies’ filings and organized the information in a structured way. Most of the information that is found in Compustat comes from Form 10-K. Most of the information in ExecuComp comes from Proxy filings (Form DEF 14A) and Forms 3–5. The merger information in SDC Platinum relies heavily on the forms filed during the period leading up to a merger. Since the introduction of EDGAR, researchers have had easy access to this “standard” information in addition to an enormous amount of information not found in any other database.

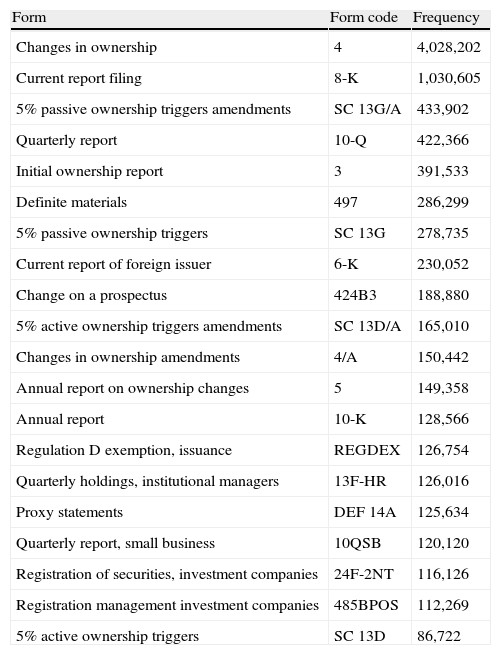

To get an idea of what type of information is available through EDGAR, we move on to looking at the most common forms filed with the SEC. Table 1 reports the filing frequency of the 20 most commonly filed forms over the period 1994–2011. The first column in the table contains a short description of the form. The second column contains the form code used on EDGAR. The third column contains the total number of times a form is filed during the whole sample period.

Most frequent EDGAR filing codes.

| Form | Form code | Frequency |

| Changes in ownership | 4 | 4,028,202 |

| Current report filing | 8-K | 1,030,605 |

| 5% passive ownership triggers amendments | SC 13G/A | 433,902 |

| Quarterly report | 10-Q | 422,366 |

| Initial ownership report | 3 | 391,533 |

| Definite materials | 497 | 286,299 |

| 5% passive ownership triggers | SC 13G | 278,735 |

| Current report of foreign issuer | 6-K | 230,052 |

| Change on a prospectus | 424B3 | 188,880 |

| 5% active ownership triggers amendments | SC 13D/A | 165,010 |

| Changes in ownership amendments | 4/A | 150,442 |

| Annual report on ownership changes | 5 | 149,358 |

| Annual report | 10-K | 128,566 |

| Regulation D exemption, issuance | REGDEX | 126,754 |

| Quarterly holdings, institutional managers | 13F-HR | 126,016 |

| Proxy statements | DEF 14A | 125,634 |

| Quarterly report, small business | 10QSB | 120,120 |

| Registration of securities, investment companies | 24F-2NT | 116,126 |

| Registration management investment companies | 485BPOS | 112,269 |

| 5% active ownership triggers | SC 13D | 86,722 |

The table presents the frequencies of appearances of different types of filings in the EDGAR database. The time period is 1993–2011. A filing is considered if and only if the same text string (i.e. “4”) appears in the form field of the EDGAR master files.

The most common EDGAR filing is Form 4. For the sample period 1994–2011 this form is filed more than four million times. Form 4 is used to report purchases or sales of securities by persons who are the beneficial owner of more than 10 percent of any class of any equity security, or who are directors or officers of the issuer of the security. This form would, for example, allow you to study the granting of options to officers or directors. Table 1 also shows that Form 4/A is a commonly used form. When “/A” is appended to a form code it means that the filing is an amendment to an existing filing. Thus, a specific corporate event could be linked to an initial filing and a subsequent string of amendments to this initial filing. Form 3 and Form 5, also prevalent in EDGAR, deal with similar ownership issues.

The second most common EDGAR filing is Form 8-K, with more than one million filings. Companies have to use this form to file information on issues that are of “material importance” for the firm. The 8-K statements include information on changes in management, new significant contracts, merger negotiations, lawsuits, etc. In the next sections of the paper we will use the 8-K Forms to illustrate how one can use simple computerized parsing to extract information from the EDGAR filings.

Another important subset of EDGAR is comprised of Form SC 13D (commonly referred to as Schedule 13D) and Form SC 13G. Filing of these forms are triggered when someone crosses the 5% ownership threshold in a firm. The 13Ds are “active” investors, say those seeking control of the firm, whereas the 13Gs are from “passive” investors. There are on the order of 1 million such filings (including amendments).

Annually and quarterly statements also figure prominently in the EDGAR system. There are well over 400,000 10-Q forms, and over 100,000 10-K statements. Other forms that come up in the “top-twenty” list in Table 1 are: foreign firms’ current reports, Form 6-K; forms having to do with issuance of securities, from prospectuses, such as Form 424B3, to exemptions from regulation D; forms specific to institutional managers, such as quarterly holdings reported on Form 13F.

Filers in the EDGAR system are uniquely identified using the Central Index Key (CIK). For the sample period 1994–2011, there are 452,830 unique CIKs in the EDGAR database. Only a fraction of these CIKs are publicly traded firms. There are many filers that are private firms. These private firms include manufacturing firms, but also hedge funds and mutual funds. You will also receive a CIK if you are filing on behalf of yourself as an individual.

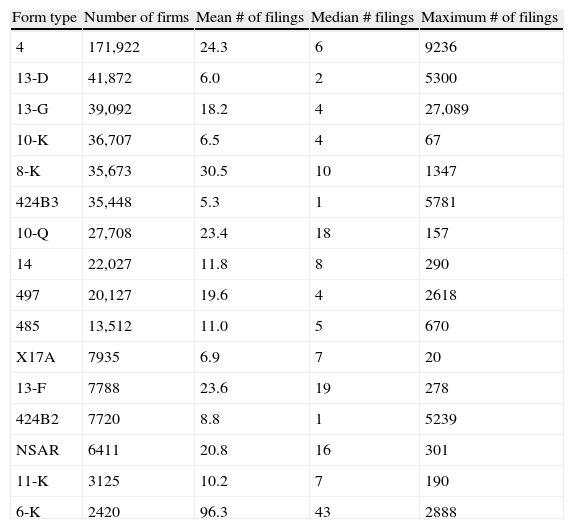

Table 2 reports the number of filers (unique CIKs) that file a particular type of form. We see there are more than 171,000 filers that have filed a form 4 (or an associated amendment) at some point during the sample period. There are about 40,000 filers that have filed 13-Ds, with a very similar number of 13-G filers. The total number of firms that file some type of 10-K report adds up to over 36,000. This is similar in magnitude to the number of firms that file 8-K statements.

Statistics on EDGAR filers.

| Form type | Number of firms | Mean # of filings | Median # filings | Maximum # of filings |

| 4 | 171,922 | 24.3 | 6 | 9236 |

| 13-D | 41,872 | 6.0 | 2 | 5300 |

| 13-G | 39,092 | 18.2 | 4 | 27,089 |

| 10-K | 36,707 | 6.5 | 4 | 67 |

| 8-K | 35,673 | 30.5 | 10 | 1347 |

| 424B3 | 35,448 | 5.3 | 1 | 5781 |

| 10-Q | 27,708 | 23.4 | 18 | 157 |

| 14 | 22,027 | 11.8 | 8 | 290 |

| 497 | 20,127 | 19.6 | 4 | 2618 |

| 485 | 13,512 | 11.0 | 5 | 670 |

| X17A | 7935 | 6.9 | 7 | 20 |

| 13-F | 7788 | 23.6 | 19 | 278 |

| 424B2 | 7720 | 8.8 | 1 | 5239 |

| NSAR | 6411 | 20.8 | 16 | 301 |

| 11-K | 3125 | 10.2 | 7 | 190 |

| 6-K | 2420 | 96.3 | 43 | 2888 |

The table presents the frequencies of appareances of different types of filings in the EDGAR database. The time period is 1993–2011. The second column presents the number of distinct firms (CIKs) that file any version of the form type listed (i.e. both forms with “4” or “4/A” are counted). Columns 3–5 present the mean/median/maximum number of filings across all CIKs that file a given form.

The three last columns of Table 2 report descriptive statistics on the number of filings of a particular form (for the subset of firms that actually file that particular form.) We see that while the number of firms that file 10-K and 8-K statements is about the same, a given firm typically files more 8-K statements than 10-K statements. On average, companies that file 8-K forms have filed over 30 such statements, while they, on average, only have filed six 10-K statements. This is most noticeable when looking at the last column in Table 2, which lists the maximum number of a given form by a given firm. Chase, the financial conglomerate, has filed a total of 1347 8-K statements. On the other hand, the firm with the most 10-K statements (Old Republic International, an insurance firm, which filed many amendments), only has a total of 67 10-K filings. This contrast is also found for other types of filings. Fidelity has filed over 27,000 13-G statements with the SEC, and GAMCO over 5000 13-D statements.

3Downloading filings from EDGARIn this section we explain how to download filings from EDGAR. The section will walk you through the following routine tasks with the EDGAR database: (a) downloading and reading quarterly master index files, (b) creating a data directory on your computer, (c) downloading all 8-Ks filed during the period 1994–2011. We provide a set of Perl routines that should be easily adapted to particular research projects.5

Perl is an open source interpreter language best known for its powerful text processing facilities.6 This makes it a natural choice for the problem at hand. The Perl code that we provide in this paper is written for a Unix operating system. But it can be easily adapted for other operating systems.

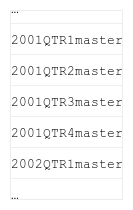

3.1Downloading quarterly EDGAR index filesTo be able to effectively download company filings from EDGAR, you will have to know where EDGAR stores the files associated with each filing made through the system. For this purpose EDGAR provides a set of quarterly index files. The index file for a specific quarter contains information about every filing made during the quarter. The first entry for the last quarterly file of 2011 reads:

The CIK of this filer is 1000032. Since this entry refers to a Form 4 filing, the filer is a person and not a company. The filing date is December 2, 2011. The textfile associated with the file can be downloaded from:

You will find all documents submitted for a given filing in the folder (the last folder name is the accession number without dashes): This folder can also be accessed using the http protocol and your favorite browser:Program 1 presents a Perl program that downloads the master files of the EDGAR database. The routine starts by calling a package, LWP::UserAgent, which is one of the many packages provided in www.cpan.org in order to interact with the Internet from a Perl script. We include others, i.e. WWW::Mechanize, in what follows. The program then opens a browser, by creating the object $ua, and then grabs files from the EDGAR ftp site, going one quarter/year at a time. The output is saved into 80 different files with the following structure:

Each master file can take as much as 30 Mb of hard disk space, especially for files during the last 10 years. The master files will be the input for the next program.3.2Organize index information by CIKAlthough it is possible to access and analyze information in EDGAR filings without downloading and saving any files to you local computer, it is more efficient to have the index files and associated filings saved locally. The reason why this saves time is that you will have to analyze documents several times during the course of a research project. Having everything locally implies that you are not vulnerable to the speed of the EDGAR ftp server. With a fast Internet connection that never goes down one can leave the files on the EDGAR server and read from there whenever necessary. But, most of us will not have this luxury.

There are many ways to organize the files and the information you download from EDGAR. We first create a directory structure with individual files that contain the entries of each individual CIK. This is clearly something of interest, as typically we want to study the behavior of particular economic entities. Furthermore, such a directory structure is a must-do when working with the amounts of data that one may need from EDGAR. Program 2 breaks the EDGAR master files into smaller master files for each CIK. The program also creates a directory structure with 906 different directories (labeled 000–905). Each directory has 500 different files, where each file stores the content of the EDGAR masterfiles for that particular CIK as a .dat file (the 906 directories work out to take care of the over 450,000 distinct CIKs).

3.3Summarizing information contained in the master filesBefore jumping into the analysis of master files, we need to give a small aside on hardware requirements for this project. The first one is obvious, sufficient disk space. The raw text files from the EDGAR database can take from over 200GB for all 8-K statements, to 10–20GB for 13D/13F/13G statements (10-K statements take up on the ballpark of 100GB). Another technical issue is the number of different files one must deal with. On a unix system, our experience is that creating directory structures with under 1000 “objects” per tree node works well (Program 2 uses 500).

Program 3 reads the *.dat files created by Program 2. To be able to find the *.dat files we have created a master list of these files using the Unix command: ls -Rl * >AllEDGARfiles.dat. If you are on a different system than Unix and do not have access to this command you may have to let Program 2 create the file AllEDGARfiles.dat.

Program 3 creates two files. The first, statsEDGAR.dat, will be used as input to other programs. This file contains: (1) the directory where the cik.dat file resides, (2) the number of EDGAR filings for that CIK, (3) the CIK number, followed by the number of filings for particular forms (namely 10-K, 10-Q, 6-K, 8-K, 4, 13G, 13D, 13F, 424B). Note how the code identifies files of different types by different means. For example, it counts forms 4 only if the string in the EDGAR file is either “4” or “4/A”. A 10Q form is defined by whether the form type contains either the strings “10Q” or “10-Q”. Table 2, discussed in the previous section, is constructed from the information in statsEDGAR.dat.

The second file created by Program 3, formtypesEDGAR.dat, is a list of all form types. It seemed to be a good idea to have a comprehensive list of all the strings that populate the form type field in EDGAR. Table 1 is constructed with information from this file. We note that we count different text strings as different types of forms, so amendments are counted as different forms in Table 1.

3.4Downloading all 8-K filings for 1994–2011We end this section with a crawling algorithm. Program 4 downloads all Form 8-K form EDGAR. The program opens statsEDGAR.dat and first looks for CIKs that have filed at least one Form 8-K. For each CIK that has filed an 8-K, it opens the local master file for that CIK, looks for the strings 8-K or 8K in the form name, and saves those appropriately to the local disk. When all 8-Ks for all CIKs are identified, lines 43 through 52 in Program 4 download the 8-K text files from EDGAR and save the file to the local hard drive. Note how the actual crawling code in Program 4 is minimal. Most of the code is simply formatting the relevant filenames correctly. In the next section we analyze the content of the downloaded 8-K filings.

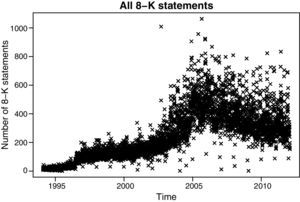

4Analyzing form 8-KSay that you are working on a project on executives, and you want to know when “material evidence” is reported by firms with respect to executive turnover. The “current report” Form 8-K discussed previously, would be a natural place to look for this type of information.7Fig. 1 plots the daily number of 8-K filings in the EDGAR database for the full sample period. It is interesting to note how there seem to be two regimes shifts. One in 1997, just after filing electronically via EDGAR became mandatory. The second shift might be related to the enaction of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in July of 2002. While these shifts are interesting on their own, we will only use the full sample of 8-K statements as a control group in what follows.

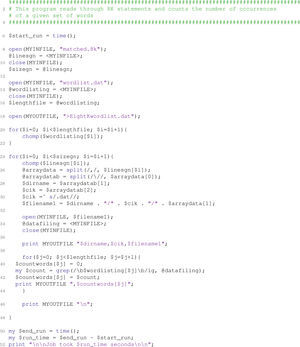

In order to gather data for a project on executives’ turnover, we need to come up with a set of text strings that we can use as keywords in a search using our 8-K database. For example, one could create a file wordlist.dat which contains the strings: departure of directors, election of directors, appointment of officers, resignation of directors. Clearly a current report (8-K) that contains such text strings will be discussing executives and corporate governance topics. The choice of strings in this example is motivated by the discussion in the EDGAR database on 8-K statements, which details what type of information should be disclosed on corporate governance and management (see in particular Item 5.02). At this point, the reader can imagine any given set of text strings that she may be interested in.

Program 5 reads through all 8-K statements in our database and counts the number of occurrences of the set of text strings saved in wordlist.dat. Since this is a particularly important type of routine, we will comment on the grep command that takes care of matching words. The command looks for occurrences of a given string, ignoring case and looking for all matches (the ig flags). The flags ∖b are “word boundaries.” This is important in some cases, as strings of text can be part of a word (rather than a whole word). The program starts by loading a list of files, from matched.8k, which is an output file from a “check” program that verifies what files were actually downloaded by Program 4.

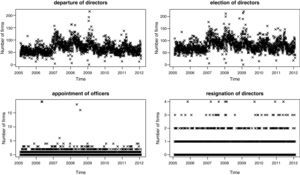

Fig. 2 plots the time-series of the number of 8-K statements that mention a given string on a given day (the string being the title of each plot), for the time period 2005–2011.8 Two of our four strings pick up a substantial number of 8-K statements: There are 123,177 8-K statements that contain “departure of directors,” and 160,258 that have “election of directors.” The other two strings are less common, with only 1478 and 1991 distinct 8-K statements mentioning “appointment of officers” and “resignation of directors.” Furthermore, the correlation between the number of 8-K statements mentioning the first two strings is over 0.9, so we collapse the two metrics into a single count of the number of 8-K statements that mention either of the two strings.9Fig. 2 and the fact that more than 15% of all 8-K statements contain the strings we tried, suggest that we have meaningful metric of executive turnover.

Since the focus of the paper is on presenting algorithms that readers can recycle for their own questions, we focus on a simple test that looks at calendar effects in executive turnover. Does turnover occur randomly throughout the year, or is there clustering around year's end? Do firms announce executive turnover questions on random days throughout the week, or do they wait to release information until Friday? The former question can rule out some economic theories in which agents do not use “anchors” such as year's end when making decisions. The latter could shed some light on the common folklore of “bad earnings announcements on Fridays.” Finally, given that we also have the time-series of all 8-K statements, we can study the same questions for the whole universe of “current reports,” and see if there are any differences.

In an attempt to answer these questions, we let Yt denote the number of firms filing an 8-K statement with either of our two strings “departure of directors” and “election of directors.” Also let Xt denote the total number of 8-K statements filed on a given day (irrespective of its content). We estimate the following models:

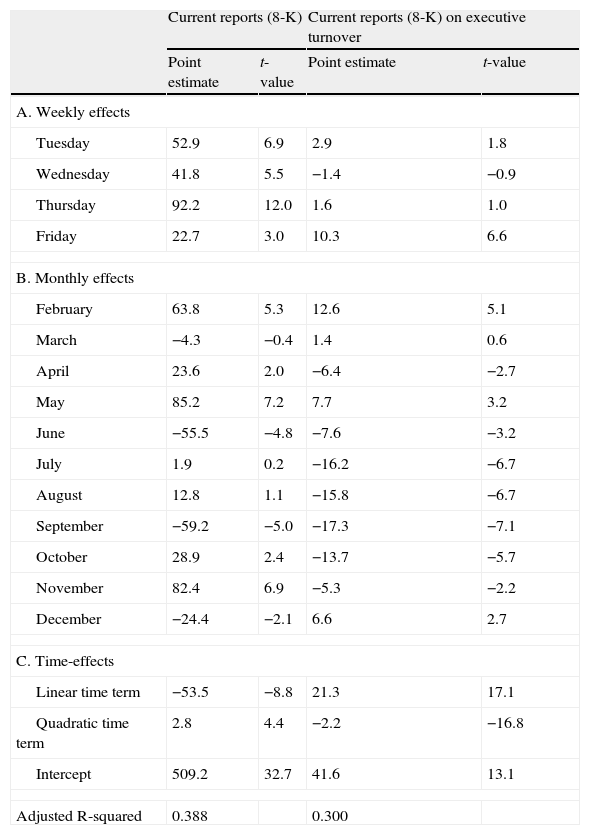

where Dt denotes a vector of day-of-the-week dummies (Monday being the omitted one), and Mt denotes month-of-the-year dummies. The vector Tt denotes time-trends controls, namely a linear term t−2004, and a quadratic term (t−2004)2. We estimate the model for the period 2005–2011.Table 3 presents the point estimates. The first two numeric columns give the results for all current report filings, whereas the last two contain those pertaining to the 8-K statements dealing with executive turnover (as defined previously). Turning to the weekly effects, we see that the dummies for Tuesday–Friday are all significantly positive. The evidence suggests that Mondays have 52.9 less 8-K statements than Tuesdays. The day of the week with the most filings is Thursday. As it turns out, Friday is the day with the second least filings, only 22.7 more than Mondays. The differences between the Tuesday–Thursday dummies, and those corresponding to Mondays and Fridays are economically large – anywhere from 20 to 90 more filings.

Calendar effects on current report filings.

| Current reports (8-K) | Current reports (8-K) on executive turnover | |||

| Point estimate | t-value | Point estimate | t-value | |

| A. Weekly effects | ||||

| Tuesday | 52.9 | 6.9 | 2.9 | 1.8 |

| Wednesday | 41.8 | 5.5 | −1.4 | −0.9 |

| Thursday | 92.2 | 12.0 | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| Friday | 22.7 | 3.0 | 10.3 | 6.6 |

| B. Monthly effects | ||||

| February | 63.8 | 5.3 | 12.6 | 5.1 |

| March | −4.3 | −0.4 | 1.4 | 0.6 |

| April | 23.6 | 2.0 | −6.4 | −2.7 |

| May | 85.2 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 3.2 |

| June | −55.5 | −4.8 | −7.6 | −3.2 |

| July | 1.9 | 0.2 | −16.2 | −6.7 |

| August | 12.8 | 1.1 | −15.8 | −6.7 |

| September | −59.2 | −5.0 | −17.3 | −7.1 |

| October | 28.9 | 2.4 | −13.7 | −5.7 |

| November | 82.4 | 6.9 | −5.3 | −2.2 |

| December | −24.4 | −2.1 | 6.6 | 2.7 |

| C. Time-effects | ||||

| Linear time term | −53.5 | −8.8 | 21.3 | 17.1 |

| Quadratic time term | 2.8 | 4.4 | −2.2 | −16.8 |

| Intercept | 509.2 | 32.7 | 41.6 | 13.1 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.388 | 0.300 | ||

The table presents the estimates of the models

where Xt denotes the number of 8-K statements filed with the SEC on a given date t, Yt denotes the number of 8-K statements filed with the SEC that contain one of the two strings “departure of directors” and “election of directors.” The variable Dt denotes a vector of day-of-the-week dummies (Monday being the omitted one), and Mt denotes month-of-the-year dummies. The vector Tt denotes time-trends controls, namely a linear term t−2004, and a quadratic term (t−2004)2.Turning to the evidence on filings having to do with executive turnover, we see a very different picture. There is virtually no statistical difference between Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, or Thursdays. On the other hand, Fridays have an average of 10.3 more 8-K statements dealing with executive turnover than a Monday. Thus, we conclude that firms do seem to be particularly fond of Fridays as a day when to file material information having to do with executive turnover. Whether this preference for the end of the week is strategic behavior by the firm, or whether it is related to the actual content of the 8-K statements, seems like an interesting avenue for future research.

We next study the seasonality along the different months of the year. The estimates are presented in Panel B of Table 3. Looking at the evidence on the full sample of 8-K statements, we find that three months are associated with particularly high levels of current reports, February, May, and November. Another three months exhibit particularly low levels, June, September, and December. This seasonality is most likely the result of other quarterly and annual filings. Recall the 8-K statements are giving regulators “material evidence” between the other required filings, most notably annual and quarterly statements. The latter acts as a substitute to 8-K statements on the months when they are filed (typically March, June, September, December).

The results for the 8-K associated with executive turnover present a significantly different pattern. The largest point estimates correspond to the months of February, May and December, whereas the six months starting in June and ending in November are associated with a significantly lower incidence of material evidence on executives.

One natural next step would be to do further text analysis of this subset of 8-K statements. We could try to extract the names of the executives involved via regular expressions, and more details as to the reasons for the departures or the background of new directors. Another possibility would be to cross our 8-K metrics, at the individual firm level, with other databases in Finance. Clearly price reactions to such announcements seem an interesting route to pursue, and using the CIK/GVKEY link file one can access both Compustat and CRSP.

5ConclusionThis short paper has presented a simple set of Perl routines to crawl and read the EDGAR database. It has presented a self-contained sequence of programs that allowed us to see when firms file material evidence outside the quarterly and annual statements (via 8-K statements), focusing on material evidence having to do with executive turnover.

The exercise itself was meant to be a simple illustration of how to access information filed through EDGAR. But we uncovered a few notable findings: Fidelity filing thousands of 13-G statements, a structural break on 8-K filings around shortly after the passing of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, and some striking difference in the timing of 8-K statements having to do with executive turnover.

While the study of 10-K statements can probably be considered mainstream finance by now, it strikes us as somewhat surprising that EDGAR filings are typically analyzed in isolation. There is clearly much to be learned about how firms sequentially release information to the market and to regulators, and the interactions between the different types of filings.

The main goal of this project was to create a set of blueprints that other researchers can use to expand our understanding of formal communications between economic entities and the SEC. The electronic materials that accompany this paper provide further scripts to study the EDGAR database. We hope that this short article will help lower the costs of the computing part of crawling EDGAR, so that financial economists can focus on finding interesting questions that may be answered with some simple Perl scripts.