Organizational innovation has always been considered as a powerful tool to sustain competitive advantage and to provide high value to customers. The purpose of this study is to empirically investigate the role of transformational leadership and knowledge management process on predicting product and process innovation. Data collected from 119 service firms located in Kingdom of Bahrain were used to test a conceptual model encompassing the linkages among transformational leadership, knowledge management process, product innovation, and process innovation. Results of hierarchical regression analyses showed that transformational leadership has direct influence over product and process innovation, and employees’ day-to-day involvement in the knowledge management process such as acquiring, transferring, and applying knowledge have positive associations with product and process innovation. Findings also revealed that knowledge transfer and application partially mediated the relationship between transformational leadership and product innovation; knowledge acquisition and application completely mediated the relationship between transformational leadership and process innovation.

Firms nowadays focus on developing appropriate leadership behaviors to confront intensive competitive pressure and to manage turbulent and uncertain environment. In order to help firms, researchers proved that transformational leadership behavior is very effective to improve organizational performance during uncertain environment and to achieve competitive advantage (for example, Nemanich & Keller, 2007). To improve organizational innovative capability, transformational leaders empower employees by providing sufficient autonomy to decide the way to perform job activities, promote organizational learning, and support employees to utilize all the available resources required to improve creativity (Aragon-Correa, Garcia-Morales, & Cordon-Pozo, 2007; Gumusluoglu & Ilsev, 2009; Jung, Wu, & Chow, 2008).

Organizations nowadays concentrate highly on activities that harness employees’ knowledge to create organizational knowledge. Therefore, they create a knowledge management system in which knowledge infrastructure supports to implement knowledge management process. As a result, this system transforms organizational resources into capabilities, which become unique to the organizations. Apart from transformational leadership, knowledge management practices also have potential to improve the level of organizational innovation. For example, knowledge transfer between organizational units promotes organizational learning and mutual cooperation, which in turn, help the organization to create a new knowledge and to improve innovation (Tsai, 2001).

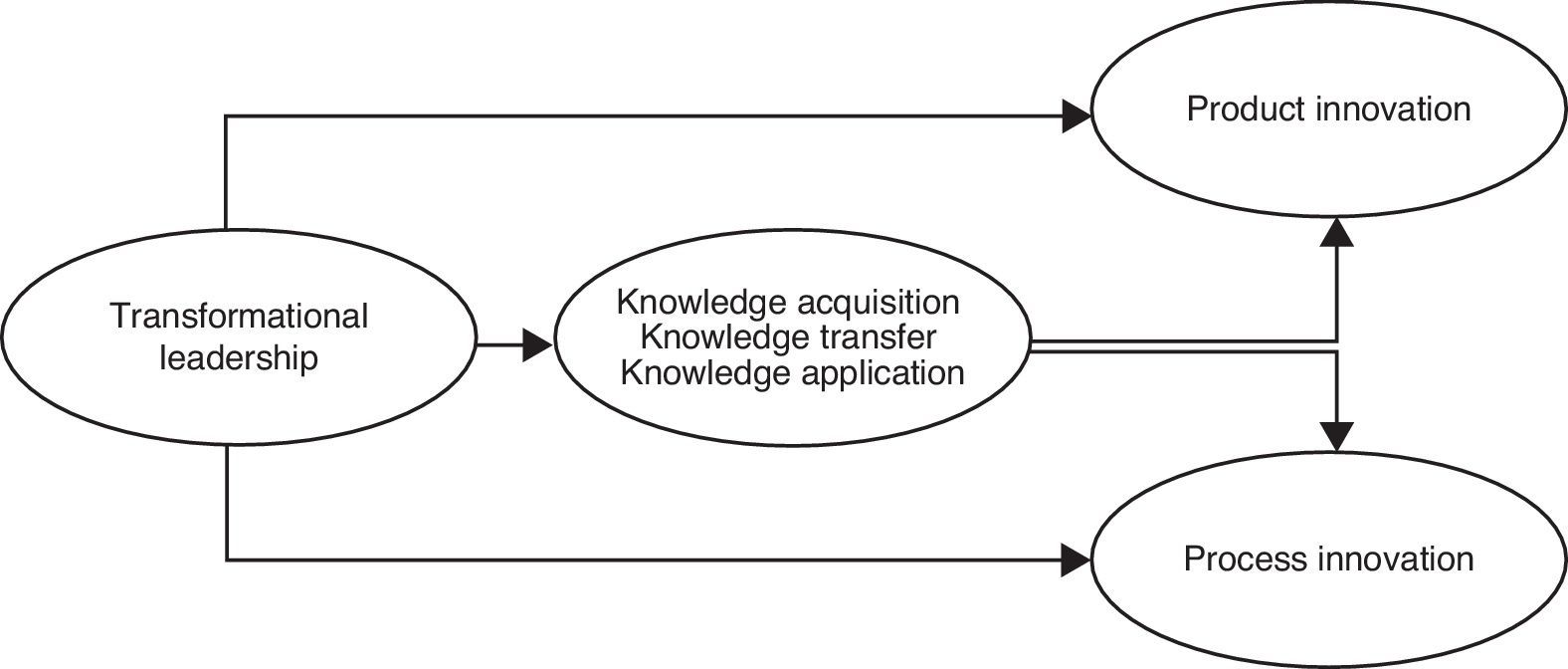

The above theories of transformational leadership and knowledge management have been given more attention for empirical investigations due to its powerful influence over organizational innovation and performance. Interestingly, though the additive effects of these theories on organizational innovation have sufficiently been explored in the literature, the additive effects of transformational leadership and knowledge management process on product and process innovation have not been explored in depth. There is also a dearth of studies explaining the combined effects of these theories on product and process innovation in the leadership literature. In this direction, this study develops a conceptual model (Fig. 1) and tests this model among service firms located in Kingdom of Bahrain. In particular, the purposes of this study are to examine the influence of transformational leadership and knowledge management process on both product and process innovation and to examine the role of knowledge management process in the relationship between transformational leadership and product and process innovation.

2Literature review2.1Transformational leadershipThe theory of transformational leadership has not been derived recently but discussions for development of such behaviors were begun among researchers in 70s (Burns, 1978). Transformational leaders are defined as leaders, who positively envision the future scenarios for the organizations, engage primarily in improving employees’ self-confidence by helping them to realize their potential, communicate an achievable mission and vision of the organizations to employees, and participate with employees to identify their needs and working out collaboratively to satisfy their needs (Peterson, Walumbwa, Byron, & Myrowitz, 2009). Based on their unconditional support to their employees, Bass (1985) identified four behaviors of this style, namely idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration and highlighted the influence of these behaviors over achieving employees’ higher order needs. Idealized influence behavior provides a strong support for employees to respect and trust leaders, encourages leaders to communicate employees the need for the blend of risk and decision-making, and most importantly, aligns leaders’ actions with the ethical ideology (Bass, Avolio, Jung, & Berson, 2003). Inspirational motivation enables leaders to set vision and mission for the future of the organization and to inspire employees toward achieving the organizational goals. Scholars describe charismatic leadership behavior as the mixture of both idealized influence and inspirational motivation (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Intellectual stimulation directs leaders to challenge employees’ ways of performing routine tasks and to question the ways they choose to derive solutions. Lastly, individualized consideration behavior showcases leaders’ mentor role of paying attention toward achieving the needs of employees and addressing the concerns of employees (Bass et al., 2003).

2.2Knowledge management processLowendahl, Revang, and Fosstenlokken (2001) classify individual employee knowledge as know-what (explicit, unambiguous, and job-oriented knowledge), know-how (tacit, difficult to express, and tenure-based knowledge), and dispositional knowledge (combined knowledge of innovativeness, creativity, ability, and intuition). It is essential for organizations to formulate a variety of strategies to convert individual employee knowledge into organizational knowledge due to the reason that individual knowledge resides within an employee's brain, and so he/she creates and stocks new knowledge with himself/herself (Nonaka, 1994). Achieving and sustaining competitive advantage mostly depends on at what extent organizations leverage and manage individual employee's knowledge. In this direction, firms establish knowledge management system in which organizational structure, technology, and culture facilitate organizations to implement knowledge management process in the forms of acquisition, transfer, and application of knowledge (Chen & Huang, 2009). Acquiring knowledge from customers, suppliers, and external professional networks represents knowledge acquisition by any firms; knowledge transfer takes place among employees or units to exchange tacit or explicit knowledge gained by an employee or a unit; and knowledge application is a process of applying the combined employees’ personal knowledge and customer or suppliers’ experiences into products or services (Birasnav, Rangnekar, & Dalpati, 2011; Filius, De Jong, & Roelofs, 2000). Activities relating to the implementation of knowledge management process transform a traditional firm into an innovative firm, and thus, a firm distinguishes itself from its competitors (Chen & Huang, 2009; Darroch, 2005).

2.3Organizational innovationInnovation, in particular technological innovation, “is an iterative process initiated by the perception of a new market and/or new service opportunity for a technology-based invention which leads to development, production, and marketing tasks striving for the commercial success of the invention” (Garcia & Calantone, 2002, p. 112). It has generally been classified as product innovation and process innovation. The introduction of new products or services in order to meet customer-driven demands in the market is called as product innovation (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001). Lukas and Ferrell (2000) and Bonner and Walker (2004) classify product innovation as product-line extensions, me-too products, new-to-the-world products, and product improvements/modifications. According to them, product-line extensions are the products produced by extending the existing product line in the current firm, and the resultant products thus become new to the customer market but not new to the current firm. Me-too products are the products that are produced by emanating the specifications of a particular product produced by the competitors, and the resultant products obviously become new to the current firm but not new to the customer market. New-to-the-world products are the products, which are newly produced by the current firm's research and development team, and so these products become new to both firm and customer market. Product improvements are the products that carry even slight modifications from the old products, and so these products will be new neither to the customer market nor to the current firm. On the other hand, the introduction of new changes in the act of producing final products or services to improve the efficiency of the internal process is called as process innovation, and so it depends on the rate of implementation of new technology in the firms (Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 2001). Lager (2002) classifies process innovation as (1) newness of process technology to the world – at what extent a particular process technology is known by the market and (2) newness of process technology to the company – at what extent a particular process technology is implemented in the production system of a particular firm. Process innovation is aimed to decrease cost associated with manufacturing process and to increase product volume. On the other hand, product innovation aimed to improve the quality of a product and to produce new products with different features (Lager, 2002).

2.4Transformational leadership and organizational innovationIn pursuit of increasing level of organizational innovation, leaders’ intellectual stimulation behaviors encourage employees to develop a pragmatic framework through which they list out all feasible solutions derived within and outside the context of a job problem. Such encouragement for independent thinking and experimentation portraits leaders as opening leaders, and fosters employees to involve in all the activities related to exploration. This explorative strategy creates more ideas and solutions and subsequently, improves organizational innovation (Jung et al., 2008; Rosing, Frese, & Bausch, 2011). Due to their idealized influence behavior, leaders love to take and share risky decisions and encourage employees to take risks while performing tasks (Bass et al., 2003). Risky decisions are very effective for producing new products, introducing unique services, or altering the production process. Individualized consideration behavior identifies employees’ level of needs and develops their potential completely. Accordingly, leaders provide monetary and non-monetary rewards to maintain employees intrinsically and extrinsically motivated (Bass et al., 2003; Zhu, Chew, & Spangler, 2005). Researchers assert that intrinsic motivation is an antecedent of firm innovation and service quality (for example, Jung et al., 2008). In addition, these leaders involve in a series of activities relating to establishing and maintaining a very supportive culture that promotes change management and gets acceptance from the stakeholders. Subsequently, they enhance organizational innovation (Jaskyte, 2004). Further, since transformational leaders having charismatic behaviors, they increase commitment among teams and promote team identity, and these result in better team innovation (Paulsen, Maldonado, Callan, & Ayoko, 2009). The above arguments provide more chances to believe that these leaders will understand the importance of both product innovation and process innovation and will equally promote these innovations in their organizations. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:Hypothesis 1 Transformational leadership will be positively related to product innovation and process innovation.

Many firms have realized the importance of implementing knowledge management programs and the need for encouraging their employees to participate in these programs, since the strength of a firm's innovative ability depends on the intensity of the implemented knowledge management process. Supporting this notion, Tsai (2001) asserts that implementation of knowledge management process promotes learning and cohesion among organizational units, and in addition to create organizational knowledge, it also increases units’ capability to innovate. In other words, involvement in the acquisition, transfer, and application of knowledge supports employees to utilize organizational resources, improves their innovative ability, and promotes firm innovation (Chen & Huang, 2009; Darroch, 2005). According to Holsapple and Jones (2004), knowledge acquisition is a process of directly or indirectly acquiring knowledge from external environment (e.g., collecting information from journals, magazines, suppliers, and customers, partnering with research institutions, recruiting employees, and acquiring another firms) and adapting it for internal use. In addition to helping to replace missing knowledge in the current firm, external knowledge also has great potential to have positive impact on the efficiency of the current firm's research and development activities when this firm gives high priority to acquire knowledge (Cassiman & Veugelers, 2006). The amount of learning from the acquired knowledge and utilization of such knowledge decide the level of firm innovation (Aragon-Correa et al., 2007; Lyles & Salk, 2007). However, increasing the intensity of knowledge acquisition also depends on the strength of ties among stakeholders of a particular organization. For example, firms having relational embeddedness – the extent to which a firm in a network is closely associated and reciprocal with others – acquired more information about new products as well as processes. At the same time, it helped firms to increase its ability to create new products and speed up the process of new product development (Rindfleisch & Moorman, 2001). Having a large network and holding a central position in that network help firms to access external knowledge and resources, to utilize know-how of its customers, to speed up its learning, to improve its products, and to introduce new products into the market (Tsai, 2001; Zahra, Ireland, & Hitt, 2000). Research study also found that trust shown by employees who participated in the collaborative projects is positively related to knowledge acquisition that had great contribution on product innovation (Maurer, 2010). Overall, knowledge acquisition enables current firms to increase its size of existing knowledge base, minimizes the length of product life cycle, and improves organizational commitment toward serving customers. Consequently, firms produce more number of new products (Yli-Renko, Autio, & Sapienza, 2001).

Knowledge transfer is a process in which knowledge gained by an employee or unit is shared with other employees or units through a systematic network. Training programs and intranet mainly help explicit knowledge transfer among employees within the organization, whereas mentor programs support tacit knowledge transfer from managers to employees. As knowledge transfer creates a variety of new knowledge, it supports introduction of new products into the market (Dayasindhu, 2002). In particular, the type of knowledge firms share with other firms should also be considered to have great impact on the innovation level. For example, sharing tacit knowledge with other firms, by maintaining a close relationship, will have an immediate effect on innovative capability of any firm. It can be reasoned that uniqueness of such tacit knowledge will be higher and cannot be found among competitors. On the other hand, the intensity of the impact of explicit knowledge transfer on innovative capability of a firm may be low due to the reason that it can be commonly found among other firms. Supporting the above notion, Cavusgil, Calantone, and Zhao (2003) found among American manufacturing and service firms that they observed higher innovative capability at a firm when it shared tacit form of knowledge with other firms. Thus, new knowledge occurs and replaces old ideas of employees or units, and organizations will strengthen its capability to adapt their processes and be able to deliver more number of customized products. Such outcomes will be strengthened further when employees or units have high absorptive capacity (Tsai, 2001). Encouraging employees to have high absorptive capacity is critical in the organization as they can quickly absorb new ideas created by their colleagues and use it for their own use and project completion. Consequently, improved creativity at the individuals is transformed into innovative processes and products at the organization level through knowledge transfer (Shalley, Zhou, & Oldham, 2004). In addition, Lin (2007) recently found that donating knowledge to other organizational members contributed to improve firm's innovative capability.

Knowledge application has been given more importance in the organizations due to the following reasons: knowledge to be applied is in tacit form, which is very difficult to apply and is requiring greater cognitive ability; knowledge application imparts new knowledge and organizational values into the new products (Chen & Huang, 2009). A study conducted among 54 new product development teams revealed that since team or individual employee usually applies knowledge, the fast decision-making process increases the number of products delivered into the market (Sarin & McDermott, 2003). It is also believed that such fast decisions will also reshape the processes established in the organizations. Thus, the above arguments lead to the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 2 Implementation of knowledge management process activities such as acquisition, transfer, and application of knowledge will be positively related to product innovation and process innovation.

It is transformational leaders, who also establish knowledge supportive culture in the forms of developing a set of values, assumptions, and beliefs related to knowledge that forges employees’ behaviors toward performing knowledge activities and engaging in knowledge management process (Birasnav et al., 2011). Implementation of this culture holds significant impact on knowledge sharing among employees, as these leaders offer employees both monetary and non-monetary rewards to share their knowledge with others, to introduce new products into the market, and to propose cost effective methods (Zhu et al., 2005). Thus, organizations improve their ability to innovate (Darroch, 2005). Researchers proved that prevalence of knowledge sharing depends on the technological capability of a particular organization (for example, Tanriverdi, 2005). In pursuit of achieving mission and vision, these leaders understand the importance of integrating employees with technology to transfer knowledge. They are often seen involving in design and implementation of new technology and influence employees to understand the usefulness of such new technology to move toward achieving mission and vision, and so employees prepare to engage in using technology in their organizations. Implementing advanced technologies like enterprise resource planning also provides unrestricted access to all the available resources within the firms, and so employees accept usefulness of new technology and reduce product development time and changeover time (Schepers, Wetzels, & De Ruyter, 2005; Wang, Chou, & Jiang, 2005). Due to individualized consideration behavior, these leaders engage in mentoring their employees, share expertize with employees, identify the needs of employees, and develop employees’ complete potential (Sosik, Godshalk, & Yammarino, 2004). Owing to these reasons, majority of employees reporting to transformational leaders attain job satisfaction, and as a result, they show improved innovative performance (Shipton, West, Parkes, & Dawson, 2006). Further, these leaders occupy a central position in the organizational network, as they are more influential and have scores of advices (Bono & Anderson, 2005). It is obvious that these leaders also improve relationship quality and interactive capability of employees, and consequently, employees acquire knowledge from suppliers and customers involved in this network and improve new product development process (Yli-Renko et al., 2001).

The inspirational behavior articulates a compelling vision and goals of the organization and develops employees’ potential to accomplish goals (Nemanich & Keller, 2007). Leaders having articulated goals identify useful external knowledge for their organizations and acquire knowledge to increase innovative performance (Lyles & Salk, 2007). It is transformational leaders, who also communicate the importance of the external knowledge to employees and improve employees’ creativity through acquiring other firms (Nemanich & Keller, 2007). Importantly, transformational leaders’ collaborative and empowering approaches help to integrate tacit knowledge of all the members, which is essential to share and apply knowledge (Kark, Shamir, & Chen, 2003; Srivastava, Bartol, & Locke, 2006). In this direction, Sarin and McDermott (2003) found that participative leaders influence employee's learning and enable them to apply knowledge. As a result, the amount of adding newness into the products increases. Based on the above arguments, the following hypothesis is proposed:Hypothesis 3 Implementation of knowledge management process will mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and product innovation and between transformational leadership and process innovation.

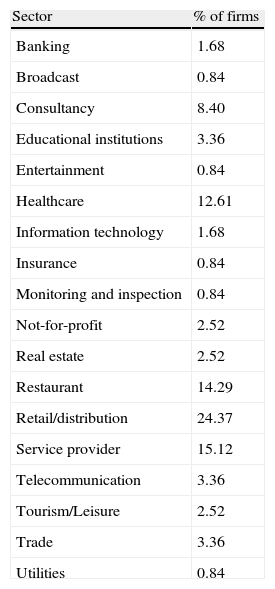

This study tested the proposed hypotheses through a survey conducted among service firms located in Bahrain. In general, the service firms are clustered together in many places of Bahrain. Due to fierce competition, service firms have been involved in updating latest technologies in their processes and delivering customized products to consumers. Therefore, improvement in the level of product innovation and process innovation can be observed very frequently and precisely in these firms. A team consisting of three postgraduate students was formed to collect responses from human resource manager and general manager/owner in each firm. Manager responsible for human resources, who reports to general manager/owner, is expertized on knowledge management process implementation. Similarly, general manager or owner of small service firms knows about their firm innovation details. A list of 500 service firms was prepared and then clustered into three groups based on the experience and knowledge of the students about a particular group. Each student was assigned to one group, and they first explained the purpose of conducting this study in the service industry to human resource manager and general manager/owner. Human resource manager was asked to rate how frequently their superior exhibits transformational leadership behaviors at them and to rate the degree of their consent on implementing knowledge management process in the firm. General manager/owner in case of a small service firm was requested to rate the firm's level of innovation on the products and processes in relation to the competitors. Thus, their responses represented the view of their firm, and data collected from only one source of a firm was considered unusable response. This team was able to gather 119 usable survey responses. Of these firms, 28 percent of firms are operating in the service industry for less than five years. Around 21 percent of firms are operating between six and ten years. About 13 percent of firms are operating between eleven and twenty years. Further, about 35 percent of firms are in operation in the industry for more than twenty-one years. 26 percent of firms have employed less than twenty-four employees for their operations. 33 percent of firms have employed between twenty-five and ninety-nine employees. More than hundred employees are working in 30 percent of firms. In addition, about 23 percent of firms have had investment of less than half million in local currency in their firms, and about 13 percent of firms have had investment between half million and one million in local currency. The capital invested in around 64 percent of the participated firms is more than one million. The percentage of firms participated from each sector of service industry is shown in Table 1. Collecting responses from these firms are necessary to understand the interrelationships among transformational leadership, knowledge management process, and the level of product innovation and process innovation. Since the participated service firms closely represent the Bahrain service industry, the findings of this study could be generalized to other firms.

Percentage of firms participated in the study.

| Sector | % of firms |

| Banking | 1.68 |

| Broadcast | 0.84 |

| Consultancy | 8.40 |

| Educational institutions | 3.36 |

| Entertainment | 0.84 |

| Healthcare | 12.61 |

| Information technology | 1.68 |

| Insurance | 0.84 |

| Monitoring and inspection | 0.84 |

| Not-for-profit | 2.52 |

| Real estate | 2.52 |

| Restaurant | 14.29 |

| Retail/distribution | 24.37 |

| Service provider | 15.12 |

| Telecommunication | 3.36 |

| Tourism/Leisure | 2.52 |

| Trade | 3.36 |

| Utilities | 0.84 |

Researchers have widely used Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) developed by Bass and Avolio (1995) for measuring leadership behaviors (Bass et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2005) and have proved that this MLQ is reliable and valid among manufacturing and service employees across many countries (for example, Judge & Piccolo, 2004). MLQ measures three kinds of leadership styles, namely transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and laissez-faire leadership, in which 20-item transformational leadership measure (Form 5X – Short, rater form) was used in this study. Human resource managers were requested to rate on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not al all) to 5 (frequently, if not always). Exploratory factor analysis (principal component analysis, varimax rotation) was performed to identify the components of transformational leadership style. Results showed that it has five reliable factors namely individualized consideration (3 items, cronbach alpha (α)=0.75), idealized influence (behavior, 4 items, α=0.83), inspirational motivation (3 items, α=0.70), idealized influence (attribute, 3 items, α=0.67), and intellectual stimulation (3 items, α=0.63). Four items were removed while interpreting factors, as these items wrongly clustered into other factors.

3.2.2Knowledge management processIn line with Lin and Lee (2005) and Chen and Huang (2009), this study considered knowledge management process as a process involves in acquisition, transfer, and application of knowledge in the firms. In this direction, Filius et al.’s (2000) 21-item measure of tactical knowledge management process comprising of knowledge acquisition, knowledge transfer, and knowledge application representing employees’ day-to-day activities was used. Responses were collected from human resource managers with the help of 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Exploratory factor analysis (principal component analysis, varimax rotation) produced five factors from this measure. However, since α values of the last two factors were less than 0.60, the four items representing these two factors were removed. Thus, three reliable factors namely knowledge acquisition, knowledge transfer, and knowledge application were considered in this study. The sample item included in the knowledge acquisition measure (4 items, α=0.75) was “our organization does research (i.e., with universities) to explore future chances/possibilities”. The sample item included in the knowledge transfer measure (5 items, α=0.75) was “much knowledge is distributed in informal ways (“in the corridors”)”. The sample item included in the knowledge application measure (8 items, α=0.85) was “we use existing know-how in a creative manner for new applications”.

3.2.3Organizational innovation9-Item measure of product innovation and process innovation developed by Prajogo and Sohal (2006) was used in this study. This measure considered four criteria of innovation characteristics such as quantity, speed, first in the market, and novelty of innovations. 5-Point Likert scale ranging from 1 (worst in industry) to 5 (best in industry) was used in this study to collect responses from general managers/owners of small firms. Exploratory factor analysis (principal component analysis, varimax rotation) resulted in two reliable factors namely product innovation and process innovation. The sample item included in the product innovation measure (5 items, α=0.81) was “the speed of our new product development”. The sample item included in the process innovation measure (4 items, α=0.79) was “the updatedness or novelty of the technology used in our processes”.

3.2.4Control variablesSince firm characteristics such as age, type, size, and capital have had certain kind of associations with innovative performance, the effects of such variables were controlled for in this study. For example, it is larger firms spending huge amount of resources to do research with universities and more time to train their employees to promote innovational activities (Laursen & Salter, 2004). In this direction, it is also expected that having huge capital will be an advantage to promote organizational innovation. It is younger firms, even though they have high probability of being quit from the industry, which receive more benefits from their innovative activities to compete in the customer market (Cefis & Marsili, 2006). Risk taking skills are essential to produce innovative products, and so public firms will have high uncertainty avoidance culture, since they have to follow rigid rules and regulations.

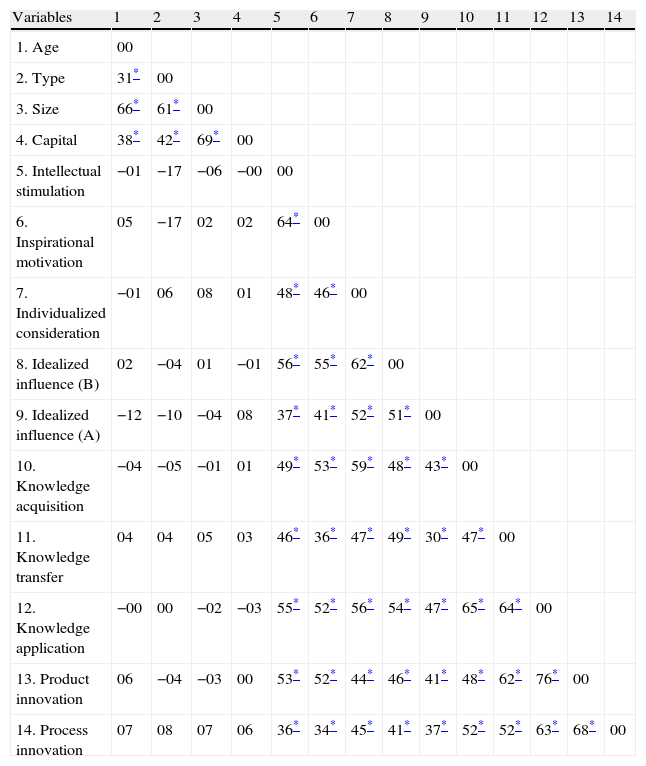

4ResultsTable 2 shows the zero order correlation coefficients between all the studying variables. The results showed that transformational leadership behaviors are positively related to knowledge acquisition, knowledge transfer, and knowledge application (r=0.30–0.59, p<0.01) and are also positively related product innovation and process innovation (r=0.34–0.53, p<0.01). The similar results are found between knowledge management variables and product innovation and process innovation (r=0.48–0.76, p<0.01).

Correlation coefficients.a

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 1. Age | 00 | |||||||||||||

| 2. Type | 31* | 00 | ||||||||||||

| 3. Size | 66* | 61* | 00 | |||||||||||

| 4. Capital | 38* | 42* | 69* | 00 | ||||||||||

| 5. Intellectual stimulation | −01 | −17 | −06 | −00 | 00 | |||||||||

| 6. Inspirational motivation | 05 | −17 | 02 | 02 | 64* | 00 | ||||||||

| 7. Individualized consideration | −01 | 06 | 08 | 01 | 48* | 46* | 00 | |||||||

| 8. Idealized influence (B) | 02 | −04 | 01 | −01 | 56* | 55* | 62* | 00 | ||||||

| 9. Idealized influence (A) | −12 | −10 | −04 | 08 | 37* | 41* | 52* | 51* | 00 | |||||

| 10. Knowledge acquisition | −04 | −05 | −01 | 01 | 49* | 53* | 59* | 48* | 43* | 00 | ||||

| 11. Knowledge transfer | 04 | 04 | 05 | 03 | 46* | 36* | 47* | 49* | 30* | 47* | 00 | |||

| 12. Knowledge application | −00 | 00 | −02 | −03 | 55* | 52* | 56* | 54* | 47* | 65* | 64* | 00 | ||

| 13. Product innovation | 06 | −04 | −03 | 00 | 53* | 52* | 44* | 46* | 41* | 48* | 62* | 76* | 00 | |

| 14. Process innovation | 07 | 08 | 07 | 06 | 36* | 34* | 45* | 41* | 37* | 52* | 52* | 63* | 68* | 00 |

Notes: Idealized influence (B) − idealized influence (behavior), idealized influence (A) − idealized influence (attribute).

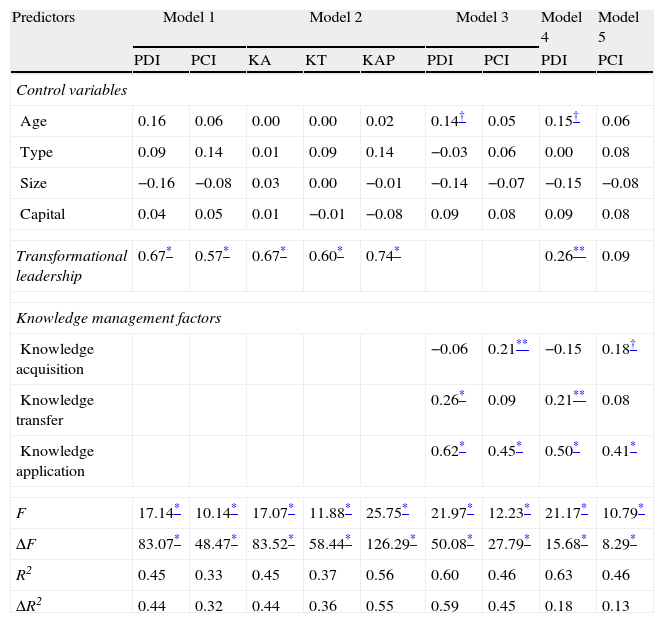

Following Zhu et al. (2005), the behaviors of transformational leadership are combined into one higher order factor, since all the behaviors have positive relationships with knowledge management process variables and product innovation and process innovation. The four-step procedure proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) for mediation analysis helped to test all the proposed hypotheses. First, there should be significant associations between transformational leadership and product innovation and process innovation. Second, there should be significant associations between transformational leadership and knowledge management variables (knowledge acquisition, knowledge transfer, and knowledge application). Third, there should be significant associations between knowledge management variables and product innovation and process innovation. Last, there should be insignificant association between transformational leadership and product innovation and process innovation, after controlling for the effects of knowledge management variables. Insignificant association would prove the pure mediation role of knowledge management variables, and significant associations with reduced beta values of transformational leadership on product innovation and process innovation would prove partial mediation role of knowledge management variables. Table 3 shows the results of hierarchical regression analyses performed by following the above said procedure. Model 1 shows the influence of transformational leadership over product innovation and process innovation. After controlling for the effects of firm characteristics (firm age, size, type, and capital), transformational leadership is positively related to both product innovation (β=0.67, p<0.01) and process innovation (β=0.57, p<0.01). These results provide strong support to hypothesis 1 stating that transformational leadership behaviors will positively be related to both product innovation and process innovation. Model 2 shows the impacts of transformational leadership behaviors on knowledge management process variables. After controlling for the influence of firm characteristics, transformational leadership significantly and positively related to knowledge acquisition (β=0.67, p<0.01), knowledge transfer (β=0.60, p<0.01), and knowledge application (β=0.74, p<0.01). Model 3 shows the effects of knowledge management variables on product innovation and process innovation. After controlling for the control variables, knowledge acquisition is positively related to process innovation (β=0.21, p<0.05); knowledge transfer has positive association with product innovation (β=0.26, p<0.01); and knowledge application has positive association with both product innovation (β=0.62, p<0.01) and process innovation (β=0.45, p<0.01). These results provide partial support to hypothesis 2 stating that implementation of knowledge management process in the organizations will have positive impact on product innovation and process innovation.

Results of hierarchical regression analyses on knowledge management process and innovation.

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||

| PDI | PCI | KA | KT | KAP | PDI | PCI | PDI | PCI | |

| Control variables | |||||||||

| Age | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.14† | 0.05 | 0.15† | 0.06 |

| Type | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.14 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Size | −0.16 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.14 | −0.07 | −0.15 | −0.08 |

| Capital | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Transformational leadership | 0.67* | 0.57* | 0.67* | 0.60* | 0.74* | 0.26** | 0.09 | ||

| Knowledge management factors | |||||||||

| Knowledge acquisition | −0.06 | 0.21** | −0.15 | 0.18† | |||||

| Knowledge transfer | 0.26* | 0.09 | 0.21** | 0.08 | |||||

| Knowledge application | 0.62* | 0.45* | 0.50* | 0.41* | |||||

| F | 17.14* | 10.14* | 17.07* | 11.88* | 25.75* | 21.97* | 12.23* | 21.17* | 10.79* |

| ΔF | 83.07* | 48.47* | 83.52* | 58.44* | 126.29* | 50.08* | 27.79* | 15.68* | 8.29* |

| R2 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.46 |

| ΔR2 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

Notes: Standardized beta coefficients are reported.

PDI – product innovation, PCI – process innovation, KA – knowledge acquisition, KT – knowledge transfer, KAP – knowledge application.

Model 4 shows the influence of transformational leadership over product innovation after controlling for the effects of knowledge management variables. The beta value of transformational leadership on product innovation is significantly reduced to 0.26 (p<0.05) from 0.67 (p<0.01). These results show that knowledge transfer (β=0.21, p<0.05) and knowledge application (β=0.50, p<0.01) are acting as partial mediators in the relationship between transformational leadership and product innovation. Model 5 shows the influence of transformational leadership over process innovation after controlling for the effects of knowledge management variables. The beta value of transformational leadership on process innovation becomes insignificant from 0.57 (p<0.01). These results show that knowledge acquisition (β=0.18, p<0.1) and knowledge application (β=0.41, p<0.01) are acting as complete mediators in the relationship between transformational leadership and process innovation. Therefore, these results provide partial support to hypothesis 3 explaining that knowledge management process will mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and product innovation and between transformational leadership and process innovation.

5Discussions5.1Implications for theoryThis study has considerably contributed to the literature by extending previous research studies in three ways. First, this study specifically proved that transformational leadership is positively related to product innovation as well as process innovation. Transformational leaders have understood that traditional firms can be transformed into innovative firms only when human capital is created within the firms. In order to develop human capital, these leaders frequently exercise empowerment among employees so that employees can make quicker decisions on changing production processes or product design. As a result, they improve employees’ innovative performance. For example, Bahrain Telecommunications Company, one of a leading telecommunication firm in Bahrain, provides emphasis on empowering employees. To develop human capital within firm, it provides training to employees to improve their skills. Transforming employees’ capabilities into organizational capabilities, this firm recently inaugurated ‘ideas center’ that showcases latest telecommunication technology and service in progress, which aimed to help this firm to deliver innovative products and services to their customers (Batelco, 2013). In this direction of improving process innovation, this firm concentrated on implementing new technologies such as 3.5G wireless HSDPA technology and fixed ADSL2+ (Kaliaropoulos, 2013). Further, understanding the linkages between risk taking and innovation, leaders’ intellectual stimulation behavior discourages employees to follow routine ways to solve job problems, rather encourages employees to involve in risky activities and decisions. At the same time, individualized consideration behavior maintains these leaders not to criticize employees in public, when risky decisions produce unfavorable outcomes.

Second, this study found that knowledge transfer and knowledge application are positively associated with product innovation, whereas knowledge acquisition and knowledge application are positively related to process innovation. In firms, knowledge transfer has been initiated in the form of requesting answers for certain difficult job questions or requesting certain specific information for making decisions in relation to new product design, specification, and development. Employees thus gain new knowledge through socializing with leaders and other employees. Further, it is very common among service firms that tasks have been associated with teamwork concepts, and so they develop and involve in networking. Since delivering a variety of new products will enable service firms to maintain its market share, they encourage collaborative problem solving, which enormously requires flow of tacit and explicit knowledge. For example, HSBC Middle East always encourages their employees to have link with network of stakeholders. Such network allows their employees to share their tacit knowledge and gain new knowledge from the external environment. Service employees usually work very close to customers, and so they depend on the experience of other employees, who experienced with similar situations, to resolve customer issues. Such knowledge transfer integrates new knowledge with existing knowledge, and employees get a useful idea or knowledge to provide newness into the customer products or services. However, service firms mostly depend on the knowledge acquisition process to update new technologies and to add newness into their processes. For example, it is often seen among Bahrain service firms’ employees that they easily monitor new technologies introduced in other firms, as these firms are clustered together in many locations. The personal interactions between the mangers of different firms and their networking behaviors also support to acquire knowledge. As most of the service firms are located very close to their suppliers and customers, they easily get feedback for their process improvement as well as new process development. In this direction, it is believed that these firms might have sought suppliers’ support for introducing new technology into their processes. Researchers have proved that supplier integration with the internal process of a firm helps to reduce cycle time, to improve quality of a particular product, and to produce technological improvements (Handfield, Ragatz, Petersen, & Monczka, 1999). Further, at what extent the organizational expertize is imparted into the products or services depends on the extent at which knowledge is effectively applied. According to Sarin and McDermott (2003), speed at which the product reaches the market and updating the internal processes rely on the capability of knowledge application. It is individual employees or a team responsible to apply knowledge, which was either generated or acquired, and so it is quite natural that fewer mistakes will emerge and decisions will be taken as quick as possible. In this direction, knowledge application significantly influences product innovation and process innovation.

Third, this study found that knowledge transfer and knowledge application partially mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and product innovation, and knowledge acquisition and knowledge application completely mediate the relationship between transformational leadership and process innovation. Since transformational leaders advise employees on problem solving and influence employees to accomplish the set targets within the time frame, these leaders occupy central position in the informal advice and influence networks within the firms. Within this network, information as well as knowledge is transferred from leaders to employees. Due to their mentoring ability, direct and personalized communication influence employees’ innovative performance through knowledge sharing. Importantly, their intellectual stimulation behavior always questions assumptions and concepts as well as seeks innovative solutions for old problems from employees. Therefore, the prevalence of knowledge sharing is inevitable within the firm, and importantly, they also reward employees who share knowledge. As these leaders are known for empowering followers, employees involving in new product team will be given freedom and autonomy to make decisions. Immediate decisions on product design would speed up introduction of new products into the market. Transformational leaders highly concentrate on acquiring knowledge from external sources such as suppliers, customers, or research institutions. For example, large service firms generally collaborate with institutions to develop new technologies, expect suppliers to participate on product quality improvement, and seek customer feedback on product design so as to eliminate unnecessary processes. Researchers provide support for this notion that it is visionary leaders or transformational leaders, who constantly maintain relationship with their suppliers and acquire knowledge to improve quality and delivery performance (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Fredendall, Hopkins, & Bhonsle, 2005). These leaders are also more favorable to introduce advanced technologies to develop flexible internal process to produce varieties of products. Such technologies help to integrate new knowledge with existing knowledge and support employees to apply this combined knowledge into the internal processes. Thus, transformational leaders, in parallel with encouraging employees to improving productivity, enhance their organization's learning capability and help to transform their organization. In line with Bass (2000) and Marsick and Watkins (2003), transformational leaders create learning organization – organization which adopts continuous learning process simultaneously with work process that enables them to quickly learn and implement changes in all of its functions. Consequently, they report positive improvements in their process innovation level.

5.2Implications for practiceThis study has numbers of implications for managers. First, it is the prime responsibility of human resource managers to develop transformational leadership behaviors among all levels of managers and therefore, developing this leadership style should be given higher importance while organizing training programs. Second, nowadays firms witness rapid changes in government regulations and strong global competition, developing this leadership style is very essential due to the reasons that transformational leaders are very effective to improve organizational performance even under uncertain environment (Nemanich & Keller, 2007). Giving importance to such style, human resource managers shall assess transformational leadership quality among candidates during recruitment and selection process, which would help firms to create a pool of qualified leaders within the firms. Third, these managers should integrate knowledge management strategy with human resource management strategy in order to improve both product innovation and process innovation. For example, managers must formulate a well-structured reward strategy to encourage employees to acquire, share, and apply knowledge. The contents related to the involvement of employees in the knowledge management process should be included in the performance appraisal process. Once employees understand that their objective career success is related to the involvement in knowledge activities, they will contribute to create organizational knowledge and improve firm innovation. Fourth, since knowledge management process is significantly related to organizational innovation, organizations should take efforts to create intraorganizational and interorganizational networks and should create awareness among employees about importance of participating in such networks. Importantly, continuously assessing employees’ participation in the networks would help human resource managers to ensure the prevalence of knowledge acquisition and knowledge transfer. Finally, managers responsible for operations should monitor their employees while applying knowledge for executing their project or solving job problems. New knowledge will significantly contribute to improve organizational innovation only when it is applied effectively.

6ConclusionsThis study contributed and added value to leadership literature through its three findings. First, it was found that transformational leadership has direct influence over product innovation and process innovation. This study is first of its kind to explore the relationship between leadership and innovation concepts separately, as most of the research studies focused innovation as a single construct. Second, knowledge management process variables have had certain positive associations with product innovation and process innovation. In particular, knowledge transfer and knowledge application were related to product innovation, whereas knowledge acquisition and knowledge application were associated with process innovation. Third, this study reported that transformational leaders improve product innovation by encouraging knowledge transfer and knowledge application among organizational members. Further, these leaders’ involvement in acquisition of knowledge from the external environment and application of new knowledge helped them to improve process innovation.

Although this study adds value to the literature, it also has certain limitations, and therefore, cautions are required to generalize the findings of this study to all the service firms. First, the responses for transformational leadership and knowledge management process measures were collected from human resource manager of a firm, and so the presence of common method bias could not be eliminated while analyzing data. Second, responses were not collected from certain sectors of service firms, for example, airlines and public educational institutions, and therefore, the sample did not completely represent the population of the study. Third, this study reported the subjective measures of product innovation and process innovation instead of objective measures. Lastly, influence of knowledge management infrastructure and interrelationships among knowledge acquisition, knowledge transfer, and knowledge application were not considered in this study. In future, the mediation role of knowledge management infrastructure will be focused in the relationship between transformational leadership and product innovation and between transformational leadership and process innovation, and the interrelationships among knowledge management system variables will also be explored. Further, the relationship between transformational leadership and knowledge management process could also be extended to predict competitive advantage.

We thank the reviewers for their valuable comments to revise this article. We thank New York Institute of Technology for providing resources to complete this study. We also thank Mr. Talal for his support in the data collection process.