Existing studies explore the demand for cinema focusing only on a single country, aiming to assess the probability of a movie's success. From a cross-country perspective, the determinants of consumer demand are relatively unexplored. The film industry may be seen as offering two heterogeneous products falling into two experiential ranges, according to their artistic content (‘art house’ films), and to the intensity of their special effects (‘mainstream’ films). This research examines the extent to which the cross country demand for the two given types of films is associated with individual, industrial, and cultural–social–structural factors. Estimation results, based on logistic regressions for a sample of OCED countries, indicate that: (1) cinema tastes diverge into different patterns across countries; (2) larger marketing investments emerge as a strong predictor of the consumption of art house films; and (3) technological level plays a significant role in creating stratified consumption for art house films.

The international film industry may be seen as offering products of heterogeneous quality falling broadly into two experiential ranges, according to their artistic content (‘art house’ films) and to the intensity of special effects (‘mainstream’ films) (Bagella & Becchetti, 1999). Typically, definitions tend to refer to the degree of ‘artistic’ versus ‘commercial’ quality (Bagella & Becchetti, 1999; Baumann, 2001), and according to several authors (e.g., Austin, 1989; Holbrook, 1999; Jansen, 2002; Wallace, Seigerman, & Holbrook, 1993), it may be reasonable to assume that most studio-produced American films aspire to the sort of mass or mainstream appeal associated with commercial success, whereas domestic films (other than American) cater more to art house crowds or to other specialized audiences.

Understanding the determinants of the consumers’ demand for cinema films has been the object of research by many scholars in various domains (Baumann, 2001; De Vany & Walls, 1999; Eliashberg & Sawhney, 1994; Lazersfeld, 1947; Smith & Smith, 1986).

The majority of the existing studies on the demand for motion pictures focus on single-country, longitudinal analyses (e.g., Bagella & Becchetti, 1999; Collins & Hand, 2005; Hennig-Thurau, Houston, & Walsh, 2006), aimed at assessing the probability of a movie's success. Therefore, viewing the demand for a given country's cinema production as a cultural (taste) marker is challenging yet feasible, based on the type of film people like and choose (DiMaggio, 1987). Given the extent to which cultural standards underlying such tastes may diverge across countries, we hypothesize that countries with higher cultural standards tend to demand relatively more art house films in comparison to mainstream films.

Our study aims to assess which are the most important determinants of the demand for ‘art house’ versus ‘mainstream’ films from a cross-country perspective. In other words, we intend to assess which factors – ‘Individual’ (consumption patterns/experiential motivation), ‘Industrial’ (films produced, average production budget, number of screens, share of creative employment), and ‘cultural–social–structural’ (population, income, level of education, field of graduation) – are most relevant in explaining cross-country choices of movie types.

The study presented in this article is, to the best of our knowledge, the first attempt to carry out an international empirical comparison of demand patterns regarding art house films versus mainstream movies. It is therefore a contribution to determine the extent to which cinema consumption reproduces the countries’ social structure in terms of high or low forms of culture. Moreover, it is important to underline that consumer research and marketing literature have paid little attention to the consumption of movies as artistic products (Wohfeil & Whelan, 2008). An understanding of the demand for cinema at the international level may be considered relevant in developing marketing strategies aimed at targeting new audiences for less mainstream films.

The study is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a review of the literature on the determinants of the demand for given types of cinema films. The methodological considerations are detailed in Section 3, and Section 4 puts forward the results of our empirical analysis encompassing a cross-country sample. Finally, we address the main conclusions and highlight some of the limitations of our study, as well as the contributions our methodology brings to the literature.

2Determinants of the demand for cinema films. A review of the literature2.1Individual factors: consumption patterns/experiential motivationCinema films are experiential goods (Cooper-Martin, 1991, 1992) that consumers engage in for fun, enjoyment and leisure (Eliashberg & Sawhney, 1994; Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982), which means that hedonic value (e.g., pleasure, thrill) is the main motive for the film experience, whereas utilitarian motives (e.g., killing time – Austin, 1989) play an ancillary role (Cooper-Martin, 1991; Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982). Thus, an active audience consumes films for goal-directed purposes (Katz, Gurevitch, & Haas, 1974).

This approach suggests that the consumer's experiential ‘needs’, such as emotional arousal, result in motivations for film demand (Austin, 1989; Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982), and that consumption and needs are associated with perceptions concerning gratifications provided by the cinema (Lichetenstein & Rosenfeld, 1983).

O’Brien (1977) indicated that film demand served creative and self-fulfilling needs and met social and entertainment goals. Austin's (1989) findings suggested that demand is positively associated with an enjoyable and pleasant activity, followed by relaxation, arousal/excitement and social activity, and that frequent cinema-goers reported a greater level of identification with these motives than occasional or infrequent ones.

For some people, motion pictures are more than just another form of entertainment through which one can spend some quality time alone or in the company of friends (Wohfeil & Whelan, 2008). For frequent cinema-goers or fans, fascination with movies meets pretty much Bloch's (1986, p. 539) definition of product enthusiasm where the product (in this case cinema films) plays an important role and is a source of excitement and pleasure along sensory and aesthetic dimensions in a consumer's life (Wohfeil & Whelan, 2008).

To sum up, some consider films as part of their appreciation for the finer things in life, regarding film as art (Baumann, 2001; Bourdieu, 1984; Holbrook & Addis, 2008), while others relish big-budget movies that have been overtly designed to entertain and reflect the popular tastes of mass audiences (Holbrook & Addis, 2008). But ultimately, what really counts for the consumer is the enjoyment of film as a holistic experience in its entirety (Wohfeil & Whelan, 2008). Whatever the motivations, in the present paper, we assume that all cinema-goers are looking for quality (Holbrook, 1999) and satisfaction in the films they choose.

When dealing with products whose quality is difficult to ascertain prior to purchase, one may expect a greater reliance on attributes that help consumers in their selection process. Mass communication researchers emphasized the importance of a film's genre as an attribute that influences cinema attendance (Austin & Gordon, 1987), meaning that an individual's preference for a given type of film may be used as a predictor of their enjoyment (Eliashberg & Sawhney, 1994). Since film type and content are not independent, the ultimate choice is based on the expectations raised by each alternative (mainstream versus art house film) to best gratify the individual's needs (Lichetenstein & Rosenfeld, 1983).

Assuming that across countries, individuals’ preferences regarding the demand for a given type of film is reflected by the top ten box-office admissions and the per capita admissions, we conjecture that:H1 The higher the market share of U.S. films in terms of the top ten box-office admissions (or per capita admissions), the lower the demand for art house films across countries.

The market success of motion pictures can be expected to be influenced by the consumers’ assessment of a movie's quality (Prag & Casavant, 1994). Quality, however, is difficult to ascertain prior to viewing, thus, audiences can interpret production budgets as signals of a movie's high quality, i.e., professionalism of concept and execution.

Increased concentration leads to market power (Hergott, 2004) and, according to Chrzanowsky (1974), economic development has brought an extension of concentration to almost every field of economy, including film production and distribution. Distribution is key to the film industry. For producers, it provides the only means by which their products reach an audience. For exhibitors, it means dealing with a more or less risky supply of films to screen (White Book, 1994), thus, financing is less problematic if producers are affiliated with a studio. It increases their chances of securing bank loans or tapping into the studio's own capital, thus securing favourable distribution and exhibition (Eliashberg, Elberse, & Leenders, 2006). Relationships between distributors and exhibitors change over time to reflect the considerable degree of mutual advantage that is to be gained by minimizing the risks that are intrinsic to the film industry (White Book, 1994).

Taking the above aspects into account and considering the weight of the market share of the most important distributors in each country, it is possible to assess the extent of concentration in the film industry. Thus, we hypothesize that:H2 The higher the degree of market concentration, the lower the demand for art house (versus mainstream) films across countries.

Motion picture demand appears to be heavily influenced by the opinions and choices of others. ‘Others’ could refer to friends and acquaintances, critics, and other opinion leaders, as well as the market as a whole (Eliashberg et al., 2006). That is why film marketers have pioneered ‘buzz marketing’, by giving opinion leaders free access to previews, with a view to stimulating positive word-of-mouth so as to sustain the film in the market. If a film does not succeed, it is usually forced out by a new product coming in behind it (Squire, 2004). Film marketing professionals believe that word-of-mouth is central to the success or failure of a film (Kerrigan, 2010).

Marketing expenditure is itself determined by production cost, the presence of a star, and film genre (Prag & Casavant, 1994). This makes sense since, when a major actor is casting, filmmakers are likely counting on the star's drawing power to attract cinema-goers. Informing people about the star's presence in the film through advertising is one way to make use of that.

A similar argument could be made about expensive productions (Prag & Casavant, 1994), since they are more appealing and a demand predictor (Basuroy, Chatterjee, & Ravid, 2003). Usually, motion pictures with higher production budgets also receive a high marketing budget (Eliashberg et al., 2006), in order to raise the consumers’ awareness of the film's quality and to influence their attitude towards it (Hennig-Thurau, Houston, & Walsh, 2006). A movie's heavy up-front investment and short life means that it has to be strongly promoted to capture audience interest prior to release, taking maximum advantage of the ‘buzz’ surrounding its opening. Studies have established a link between marketing expenditure and box-office revenue (Prag & Casavant, 1994; Zufryden, 1996, 2000).

Film consumption is characterized by network externalities arising from phenomena of mimicry and social infectiousness. To reduce their uncertainty about the quality of films, most consumers tend to consume films they have heard about (from friends, press, publicity) or which achieve the most commercial success (Moreau & Peltier, 2004). In this line of reasoning, films’ marketing expenditure may influence the corresponding demand.

In short, film consumption seems to be heightened by investments in publicity and by the power of distributors resulting in a concentration of admissions to a limited number of films. In this vein, we posit that:H3 The higher the investment in the marketing of low-budget films, the higher the demand for art house films across countries (i.e., the share of domestic films released in a given country).

Researchers in stratification (Bourdieu, 1984; DiMaggio, 1994; Katz-Gerro, 1999) pointed out the relatively close connection between various social status indices and cultural consumption. According to Bourdieu (1989) and Ritzer (1992), cinema consumption and orientation is not objectively determined, nor is it the outcome of free will, but rather the result of the dialectical relationship between action and structure and the outcome of this dialectical discourse is the ‘habitus’. Bourdieu (1989) defines habitus as consisting of resources or capital derived from one's socialization in society. It composes the individual's personal cultural baggage and taste in such things as music and film which reflect objective divisions in the class structure.

Drawing on the work of Bourdieu (1989), López-Sintas and García-Álvarez (2006) examined the link between social class and types of audiovisual consumption, and their findings demonstrated that it is easier to find film and audiovisual fans in higher classes than in any other category. Collectively, existing studies have established a clear and pervasive connection between education and an appreciation for high culture (DiMaggio & Useem, 1978; Gans, 1974; Snowball, Jamal, & Willis, 2010).

It has also been suggested that people with a high educational level have a relatively higher income (Augedal, 1972) and the probability of going to the cinema rises with income, which contradicts the theory of “escapism for the masses” (Collins & Hand, 2005).

In the case of films, Bourdieu (1984) also emphasizes the oppositions found in the field of cinema where he concludes that professional occupations with more cultural capital than economic capital, generally prefer art films “that demand large cultural investment”, whereas business occupations, possessing more economic capital than cultural capital, tend to prefer mainstream films, defined as those “spectacular feature films, overtly designed to entertain”.

Recent technological advances in the film industry, as well as in related industries, have revolutionized the industry's production processes, distribution channels, and consumption trends. The rise of digital film production with new methods, more creative contents, and the rapidly increasing digitization of cinemas is creating a window of opportunity for international cinema, with centres of innovation in permanent change (Cousins, 2004). Thus, it is likely that differences in the countries’ technological level will lead to differences in film consumption patterns. We therefore propose that:H4 The higher the social and cultural status of a population, the higher the demand for art house films across countries.

Our dependent variable ‘Demand for art house versus mainstream film’ is taken as a dummy-variable which assumes the value of 1 when the market share of art house films is below a given threshold. The aim here is to assess which are the main determinants of the propensity of the demand for art house films in comparison to mainstream ones. The nature of the data observed regarding the dependent variable [‘Demand for art house films at a given threshold (dummy=1 if Yes and 0 if No)] dictates the choice of the estimation model. Conventional estimation techniques (e.g., multiple regression analysis), in the context of a discrete dependent variable, are not a valid option. Firstly, the assumptions needed for hypotheses testing in conventional regression analysis are necessarily violated – it is unreasonable to assume, for instance, that the distribution of errors is normal. Secondly, in multiple regression analysis the predicted values cannot be interpreted as probabilities – they are not constrained to fall in the interval between 0 and 1. The logistic regression model is also preferred to another conventional estimation technique, discriminant analysis. According to Hosmer and Lemeshow (1989), even when assumptions required for discriminant analysis are satisfied, logistic regression still performs well.

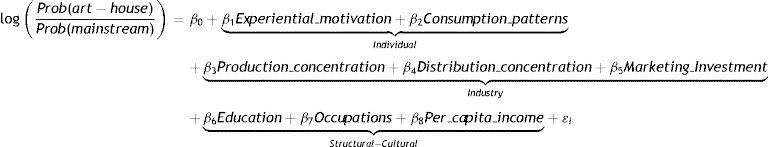

The approach used, therefore, involves analyzing each situation in the general framework of probabilistic models. The empirical assessment of the propensity of the demand for art house films is based on the estimation of the following general logistic regression, which in order to obtain a more straightforward interpretation of the logistic coefficients, can be rewritten in terms of the odds of an event occurring. Thus, the logit model becomes:

The logistic coefficient can be interpreted as the change in the log odds associated with a one-unit change in the independent variable. Then e raised to the power βi is the factor by which the odds change when the ith independent variable increases by one unit. If βi is positive, this factor will be greater than 1, which means that the odds are increased; if βi is negative, the factor will be less than one, which means that the odds are decreased. When βi is 0, the factor equals 1, which leaves the odds unchanged.

We estimated three models, depending on the threshold considered for the proxy of the dependent variable: market share of domestic films (proxy for art house films) below a given threshold.

3.2Construction of the proxies and data sourcesWe built our database using 30 OECD countries, both because of the ease of data gathering and, most importantly, because of the composition of this sample. Indeed, OECD membership includes not only European countries but also Canada, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Korea, and the United States, which expresses different realities in the cultural field of cinema. To measure the cross-country demand for art house versus mainstream motion pictures, the reference year of 2007 was used, the most recent year for which we were able to obtain statistical information. In a volatile market as the movie industry this is likely to constitute a major pitfall; however, the novelty of the analysis pursued in the present paper open ups new and challenging path for future research once additional data is available.

The measures of the constructs (proxies) were derived from a number of different sources available. The data was gathered from various organizations and was based on the analysis of the countries’ macro statistics, provided mainly by the OECD, EU, the countries’ official government sources, and cinema statistics systems in place in the selected countries. When available, we preferred to gather data from the European Audiovisual Observatory because it provides a greater guarantee of homogeneity among the data from the different countries in the sample. We did not consider important film industries of countries such as India and Nigeria, which might be considered a limitation of this study, due to a lack of (macro and industry) statistical data. Although the number of films produced in India and Nigeria are greater than that of the U.S., the figures do not correlate to the level of international exposure. The Nigerian film industry is also more focused on video distribution and films are watched either at home or in video parlours, places where communities come together to watch films (Kerrigan, 2010).

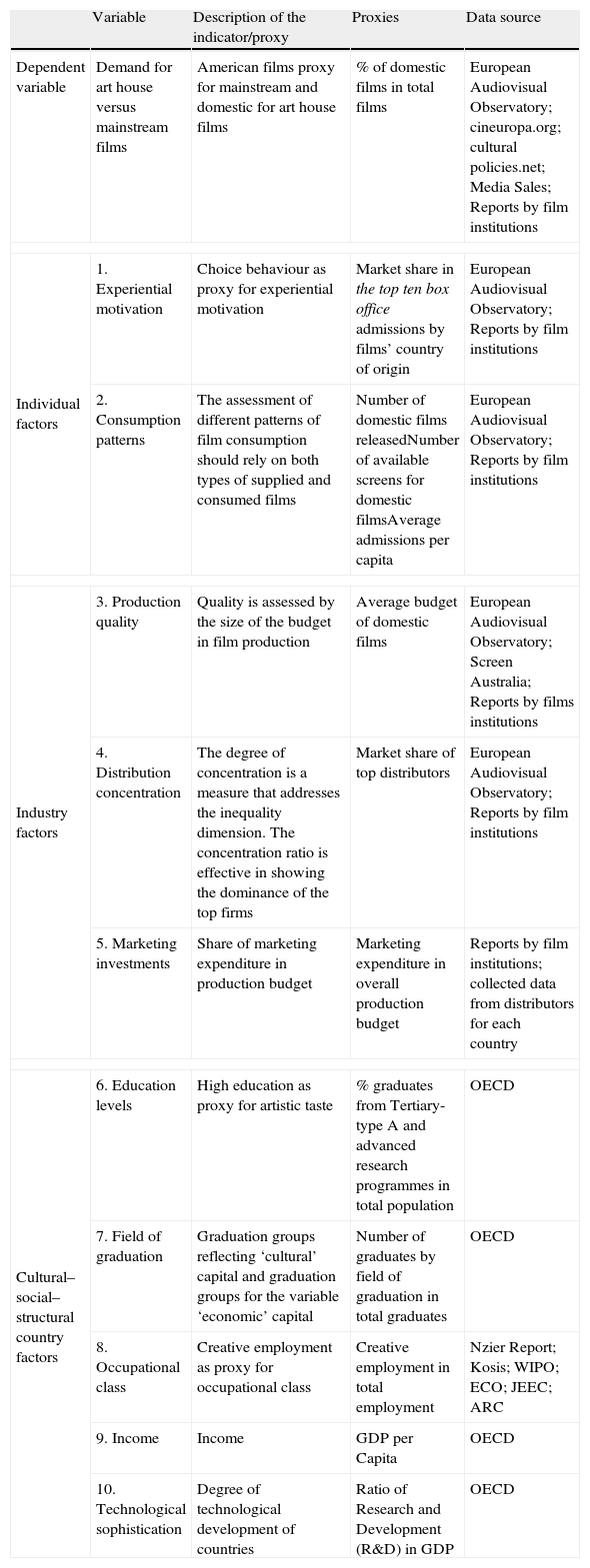

Table 1 summarizes the proxies used for the dependent and explanatory variables.

Summary of variables and proxies of the model.

| Variable | Description of the indicator/proxy | Proxies | Data source | |

| Dependent variable | Demand for art house versus mainstream films | American films proxy for mainstream and domestic for art house films | % of domestic films in total films | European Audiovisual Observatory; cineuropa.org; cultural policies.net; Media Sales; Reports by film institutions |

| Individual factors | 1. Experiential motivation | Choice behaviour as proxy for experiential motivation | Market share in the top ten box office admissions by films’ country of origin | European Audiovisual Observatory; Reports by film institutions |

| 2. Consumption patterns | The assessment of different patterns of film consumption should rely on both types of supplied and consumed films | Number of domestic films releasedNumber of available screens for domestic filmsAverage admissions per capita | European Audiovisual Observatory; Reports by film institutions | |

| Industry factors | 3. Production quality | Quality is assessed by the size of the budget in film production | Average budget of domestic films | European Audiovisual Observatory; Screen Australia; Reports by films institutions |

| 4. Distribution concentration | The degree of concentration is a measure that addresses the inequality dimension. The concentration ratio is effective in showing the dominance of the top firms | Market share of top distributors | European Audiovisual Observatory; Reports by film institutions | |

| 5. Marketing investments | Share of marketing expenditure in production budget | Marketing expenditure in overall production budget | Reports by film institutions; collected data from distributors for each country | |

| Cultural–social–structural country factors | 6. Education levels | High education as proxy for artistic taste | % graduates from Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmes in total population | OECD |

| 7. Field of graduation | Graduation groups reflecting ‘cultural’ capital and graduation groups for the variable ‘economic’ capital | Number of graduates by field of graduation in total graduates | OECD | |

| 8. Occupational class | Creative employment as proxy for occupational class | Creative employment in total employment | Nzier Report; Kosis; WIPO; ECO; JEEC; ARC | |

| 9. Income | Income | GDP per Capita | OECD | |

| 10. Technological sophistication | Degree of technological development of countries | Ratio of Research and Development (R&D) in GDP | OECD | |

Regarding the dependent variable, various scholars (Baumann, 2001; Bordwell & Thompson, 2006) have emphasized the contrast between mainstream and art house films. In this context, numerous studies (e.g., Bagella & Becchetti, 1999; Holbrook & Addis, 2008) have tested the widespread assumption that high-budget productions are more connected to the mainstream, and low-budgets are more related to art house films. On the matter of country of origin, and according to the literature, we have set mainstream films as American films and art house films as domestic films (other than American).

In what concerns the explanatory variables, and more particularly individual factors – experiential motivation and consumption patterns –, ‘experiential motivation’ suggests that consumption and needs are associated with perceptions, and that the individuals’ choice is based on the attributes of each film that best gratify their needs. To have experience value, a film needs to differentiate its content in terms of both narrative and aesthetics (Burke, 1996). If cinema-goers place high value on the film they want to see, it is believed they will engage in behaviour to demand for it. Looking at the distribution of admissions over the total number of released films seems a proper indicator of consumed diversity that makes it possible to assess whether consumers tend to go to the same films or, on the contrary, each film obtains a similar audience. Given that it was impossible to obtain the complete set of data on the distribution of admissions by film as it is unavailable for most countries, we calculated the domestic/mainstream film market share in the top ten box-office admissions by country of origin. This provides a proxy measure for assessing the individual's behaviour.1 Assessment of behaviour stands as a proxy for experiential motivation to see a mainstream or art house film.

The assessment of different patterns of film consumption should rely on both types of supplied and demanded cinema films.

The variety supplied is measured by the number of produced and released films in a given country over the year 2007, and by the number of available screens. To determine the proportion of the films released in countries where data was unavailable (released films by origin) we requested a list of all films released in 2007 from the countries’ film institutions. After receiving the lists, we searched each movie, one by one, on the Internet Movie Database (IMBD) site,2 to ascertain the geographic origin of production. This task gained an important dimension in this research study for two reasons: first, because without this exhaustive effort we would not have been able to build our database, and secondly, due to increasing international co-production arrangements. Today, nations often band together, either to pool funds or creative resources and the supra-national identities of these films often raise difficulties in the concept of national cinema.3 Despite the legitimate problems in attempting to attribute the national identities to certain films, the IMBD provided valuable information which, in cases of doubt, enabled decisions with high levels of accuracy in relation to our database.4

On the consumption side, an intense level of demand is a necessary condition for the consumption of the two different types of films. Intense demand maximizes the chance that each film supplied will be consumed. The variety consumed is thus evaluated on the basis of average admissions per capita.

Regarding the industry factors (production quality, distribution concentration and marketing investments), film's production quality is difficult to ascertain prior to viewing, thus, audiences can interpret production budgets as signals of a film's high quality, i.e., professionalism of concept and execution (Prag & Casavant, 1994). Thus, the average budget of domestic films is used as a proxy for the production quality of domestic films.

The concentration ratio is effective in showing the dominance of the top firms and, from this perspective, industrial concentration can be measured using the distributors’ market share and the possible impact on the consumer's choice across countries, since exhibitors also receive a constant proportion of domestic box office revenue.

It is important to note that our variable ‘average film marketing investments’ includes P&A (prints and advertisement). Prints are the actual physical films that are shown in cinemas. Each cinema needs at least one print and possibly more depending on how many screens the film is playing on. The advertising part of the P&A budget is the amount spent on just that, advertising (TV, newspapers, magazines, internet, cinema advertising). Another proper measure to assess marketing investments is the number of copies released per film. This would enable us to measure the degree of inequality in competition among different films. Unfortunately, this data is not available for all the different countries in the sample. Thus we adopted the approach of Zuckermann and Kim (2003), who suggested a two-tiered market structure in which the market share is mirrored and, indeed largely determined, by a corresponding inequality in the number of screens allocated to the film type (Zuckermann and Kim, 2003). As proxies, we use the average film marketing expenditure in the overall production budget5 and the available screens for each type of film (cf. Table 1).

As referred earlier, high education is likely to be a good proxy determinant of artistic taste. In order to test this hypothesis we use the number of graduates from Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmes in each country. Moreover, consumption of cinema films is reinforced during the process of education; therefore, it is more likely that people with similar education backgrounds will resemble each other in leisure habits (Katz-Gerro, 1999). From our data sources we were able to construct seven groups by field of graduation. Four groups were used (humanities, arts, behavioural and social sciences, journalism and information) to reflect ‘cultural’ capital and three groups (business, engineering, computing) for the variable ‘economic’ capital.

Since exposure to cultural capital is, to a considerable extent, a function of occupational class, cultural capital is also likely to contribute to the class differentiation of arts consumption. We assume that within each country, the higher the cultural occupational class (defined by the percentage of creative and cultural employment in the overall employment), the higher the consumption of domestic films.

The first step in assessing the occupational classes in the creative and cultural industries is to define corresponding sectors and activities. This is no easy task given the divergence of national and international approaches, the problem with the comparability of definitions, statistical frameworks, data and indicators (KEA, 2006). For the purposes of this study, we use the following definition of creative and cultural industries: those concerned with the creation and provision of marketable outputs (goods, services and activities) that depend on creative and cultural inputs for their value (Power & Nielsen, 2010).6

According to the literature, people with a high educational level have, on average, a relatively higher income/development (Augedal, 1972; Lazarsfeld, 1947). Thus, it is expected that the differences in income per capita (proxy for ‘status’) between countries will result in distinct audience statuses, and therefore, in distinct types of film consumption.

Finally, the percentage of a country's GDP allocated to R&D activities is used as a proxy to assess the impact of the film industry's technological level. It is expected that the most technologically developed countries are likely to attract more audiences to its films as filmmaking practices become more innovative, given their high level of technological sophistication.

4Determinants of the demand for art house versus mainstream films: results from the estimation of the logistic modelAbout 60% of the (30) countries in our sample present an average ratio of art house (domestic) films to people attending mainstream (U.S.) films above 10%. If the threshold is set at 20%, the percentage of countries decreases to 36.7%.7 It is important to note that the demand for domestic films is, for the generality of countries, very low. According to UNESCO's data, and considering the average for the period 2006–2011, of the 42 countries with data available, a very limited number (9) registered a value for the share of domestic films (in terms of Gross Box Office, that is, total revenue from ticket sales, including VAT and/or other taxes) above 20% (no country registered a figure above 50%).8 Based on such evidence, one might conclude that to present a ratio of domestic films in total films above a threshold of 10%/20% is considered a rather high/very high share.

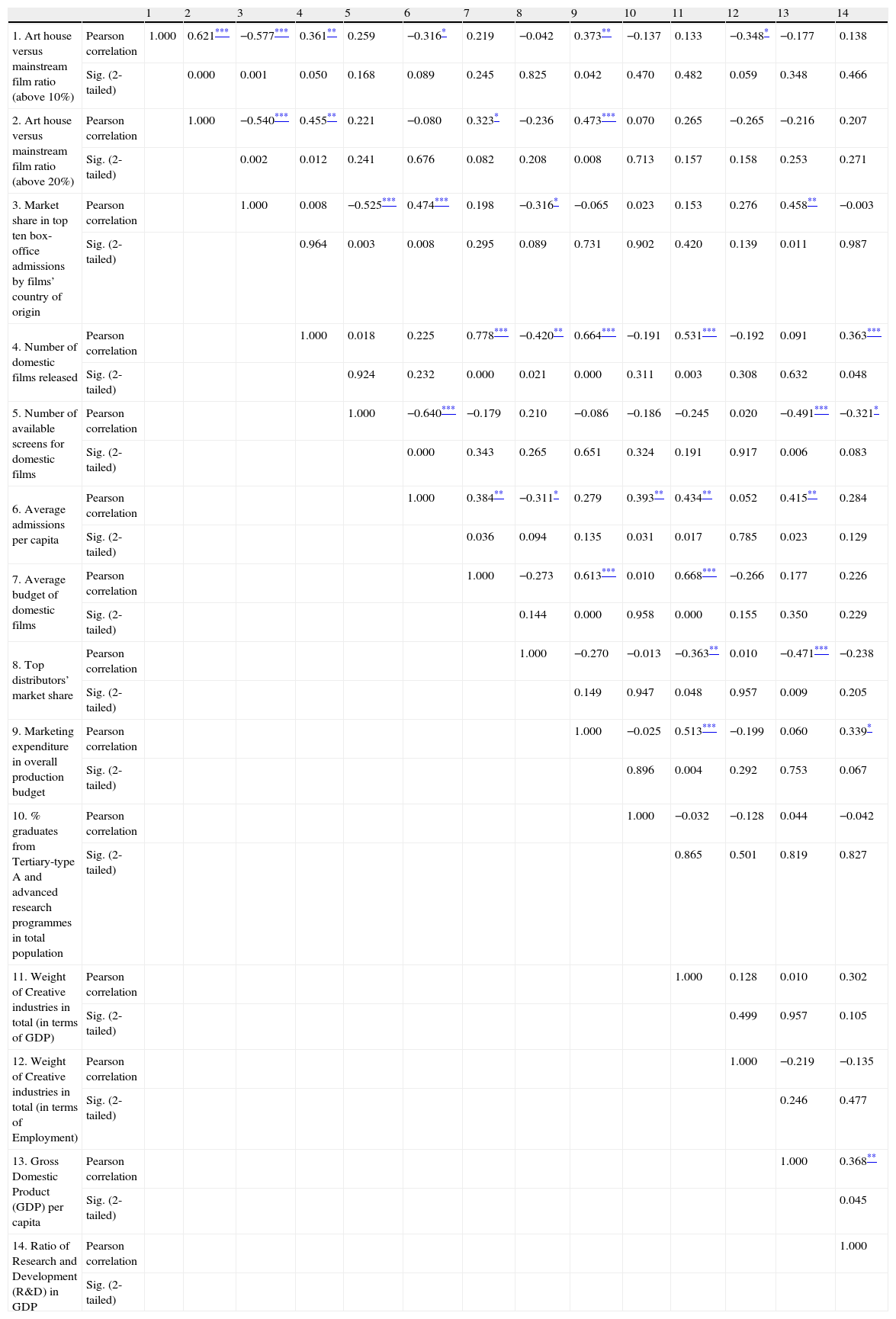

On average and in a bivariate perspective (cf. Table 2), the demand for art house films is positively associated with the supply of domestic films, their quality and marketing investments. In order to effectively and rigorously analyze the determinants of the (relative) demand for art house films (proxied by the 10% or 20% threshold variable for the art house versus mainstream film ratio), a multivariable analysis is required. Aiming to avoid multicollinearity problems, but guaranteeing that a variable proxy is added for each group of factors/determinants of the relative demand for art house films, we decided to remove some variables, which present very high correlation coefficients (above 0.50), from the logistic model presented in Table 3. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test indicates that the two models estimated represent ‘reality’ well, that is, there is a reasonable goodness of fit.9 Moreover, more that 86% of the estimated values of the dependent variable are correctly predicted by the model.

Correlation matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||

| 1. Art house versus mainstream film ratio (above 10%) | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | 0.621*** | −0.577*** | 0.361** | 0.259 | −0.316* | 0.219 | −0.042 | 0.373** | −0.137 | 0.133 | −0.348* | −0.177 | 0.138 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.050 | 0.168 | 0.089 | 0.245 | 0.825 | 0.042 | 0.470 | 0.482 | 0.059 | 0.348 | 0.466 | ||

| 2. Art house versus mainstream film ratio (above 20%) | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | −0.540*** | 0.455** | 0.221 | −0.080 | 0.323* | −0.236 | 0.473*** | 0.070 | 0.265 | −0.265 | −0.216 | 0.207 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.241 | 0.676 | 0.082 | 0.208 | 0.008 | 0.713 | 0.157 | 0.158 | 0.253 | 0.271 | |||

| 3. Market share in top ten box-office admissions by films’ country of origin | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | 0.008 | −0.525*** | 0.474*** | 0.198 | −0.316* | −0.065 | 0.023 | 0.153 | 0.276 | 0.458** | −0.003 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.964 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.295 | 0.089 | 0.731 | 0.902 | 0.420 | 0.139 | 0.011 | 0.987 | ||||

| 4. Number of domestic films released | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | 0.018 | 0.225 | 0.778*** | −0.420** | 0.664*** | −0.191 | 0.531*** | −0.192 | 0.091 | 0.363*** | |||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.924 | 0.232 | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.311 | 0.003 | 0.308 | 0.632 | 0.048 | |||||

| 5. Number of available screens for domestic films | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | −0.640*** | −0.179 | 0.210 | −0.086 | −0.186 | −0.245 | 0.020 | −0.491*** | −0.321* | ||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.343 | 0.265 | 0.651 | 0.324 | 0.191 | 0.917 | 0.006 | 0.083 | ||||||

| 6. Average admissions per capita | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | 0.384** | −0.311* | 0.279 | 0.393** | 0.434** | 0.052 | 0.415** | 0.284 | |||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.036 | 0.094 | 0.135 | 0.031 | 0.017 | 0.785 | 0.023 | 0.129 | |||||||

| 7. Average budget of domestic films | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | −0.273 | 0.613*** | 0.010 | 0.668*** | −0.266 | 0.177 | 0.226 | ||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.144 | 0.000 | 0.958 | 0.000 | 0.155 | 0.350 | 0.229 | ||||||||

| 8. Top distributors’ market share | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | −0.270 | −0.013 | −0.363** | 0.010 | −0.471*** | −0.238 | |||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.149 | 0.947 | 0.048 | 0.957 | 0.009 | 0.205 | |||||||||

| 9. Marketing expenditure in overall production budget | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | −0.025 | 0.513*** | −0.199 | 0.060 | 0.339* | ||||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.896 | 0.004 | 0.292 | 0.753 | 0.067 | ||||||||||

| 10. % graduates from Tertiary-type A and advanced research programmes in total population | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | −0.032 | −0.128 | 0.044 | −0.042 | |||||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.865 | 0.501 | 0.819 | 0.827 | |||||||||||

| 11. Weight of Creative industries in total (in terms of GDP) | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | 0.128 | 0.010 | 0.302 | ||||||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.499 | 0.957 | 0.105 | ||||||||||||

| 12. Weight of Creative industries in total (in terms of Employment) | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | −0.219 | −0.135 | |||||||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.246 | 0.477 | |||||||||||||

| 13. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | 0.368** | ||||||||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.045 | ||||||||||||||

| 14. Ratio of Research and Development (R&D) in GDP | Pearson correlation | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

Note: The variables referring to education type (field of graduation) were omitted for the sake of space.

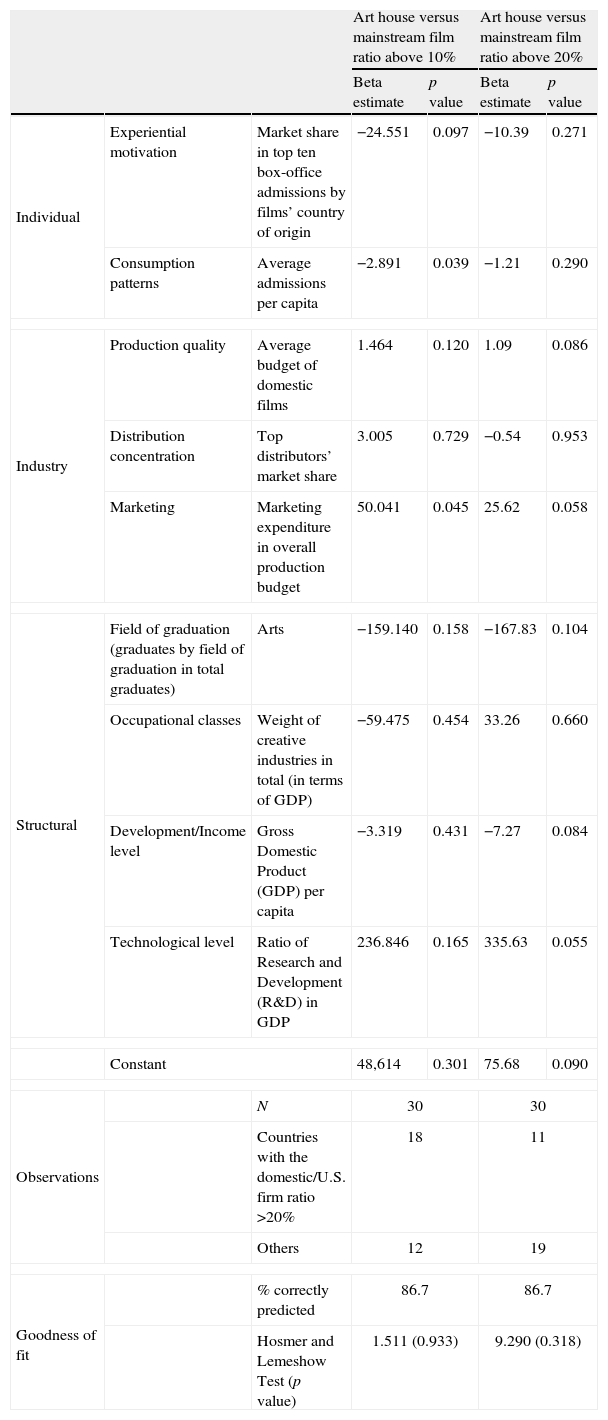

Determinants of the demand for art house versus mainstream films – estimation results.

| Art house versus mainstream film ratio above 10% | Art house versus mainstream film ratio above 20% | |||||

| Beta estimate | p value | Beta estimate | p value | |||

| Individual | Experiential motivation | Market share in top ten box-office admissions by films’ country of origin | −24.551 | 0.097 | −10.39 | 0.271 |

| Consumption patterns | Average admissions per capita | −2.891 | 0.039 | −1.21 | 0.290 | |

| Industry | Production quality | Average budget of domestic films | 1.464 | 0.120 | 1.09 | 0.086 |

| Distribution concentration | Top distributors’ market share | 3.005 | 0.729 | −0.54 | 0.953 | |

| Marketing | Marketing expenditure in overall production budget | 50.041 | 0.045 | 25.62 | 0.058 | |

| Structural | Field of graduation (graduates by field of graduation in total graduates) | Arts | −159.140 | 0.158 | −167.83 | 0.104 |

| Occupational classes | Weight of creative industries in total (in terms of GDP) | −59.475 | 0.454 | 33.26 | 0.660 | |

| Development/Income level | Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita | −3.319 | 0.431 | −7.27 | 0.084 | |

| Technological level | Ratio of Research and Development (R&D) in GDP | 236.846 | 0.165 | 335.63 | 0.055 | |

| Constant | 48,614 | 0.301 | 75.68 | 0.090 | ||

| Observations | N | 30 | 30 | |||

| Countries with the domestic/U.S. firm ratio >20% | 18 | 11 | ||||

| Others | 12 | 19 | ||||

| Goodness of fit | % correctly predicted | 86.7 | 86.7 | |||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test (p value) | 1.511 (0.933) | 9.290 (0.318) | ||||

Measuring taste by consumption performance, we found support for the general principle that cinema tastes are likely to diverge into different patterns across-countries. Our results reveal mixed support for H1. Indeed, in the case of the model at the 10% threshold (but not the 20% threshold), the estimates for the coefficients of our individual factor show that the higher the proportion of admissions to U.S. films in the top ten box office admissions, and the higher the average admissions per capita, when controlled and keeping the other variables constant, the lower the relative demand for art house films.

In terms of industry factors, our predictions for production quality (i.e., H2) are also corroborated, but this time only in the case of the 20% threshold. In other words, when we consider as the dependent variable the dummy variable that assumes the value of 1 when the ratio of art house versus mainstream films is above 20%, there is enough statistical evidence to state that, other factors remaining constant, the larger the domestic production budget, or the higher the domestic film quality, the higher the relative demand for art house films. This finding is consistent with most previous studies which consider that the production budget is an important indicator of a movie's quality (Prag & Casavant, 1994), and is thus a good predictor of movie attendance (Basuroy et al., 2003). Also, the empirical findings of Hennig-Thurau, Houston, and Sridhar (2006) sustain the important impact of a film's production quality on consumer word-of-mouth, which is a key determinant of long-run box office success.

H3 is unambiguously proven by our estimations. We found that, regardless of the dependent variable used, marketing investments emerge as a key determinant in the consumption of art house films. In other words, the higher the investments in marketing, on average, the higher the demand for art house films, keeping other variables constant. Thus, there is a high likelihood that the relative demand for art house films be predicted from the amount invested (from the total production budget) in marketing. These results are in line with findings in existing literature. For instance, Prag and Casavant (1994) highlighted the importance of marketing expenditure in determining a film's demand and performance at the box office.

Finally, in what concerns the social-structural factors, the estimation results yielded mixed support of our hypothesis (H4). Education- and occupation-related variables failed to emerge as statistically significant, which means that for the sample of countries considered here we do not possess sufficient evidence, other factors remaining constant, that could distinguish countries according to their relative demand for art house films based on their education and occupation profiles.

Unexpectedly, when we control for other factors likely to influence the relative demand for art house films, the countries’ level of development emerges significantly and negatively related with that demand (although only in the case of the 20% threshold). Although contradicting in part the idea of ‘status’ associated with higher income (or development) levels, such results may be consistent with other findings in the literature. For example, Peterson and Kern (1996) found that members of the upper-middle class have become less “snobbish” and more “omnivorous” in their tastes in recent years, which means that one of the cultural characteristics of the upper-middle class is “an openness to appreciating everything” (Peterson & Kern, 1996, p. 904). The omnivore's cultural repertoire cuts across the aesthetics spectrum as their taste is developed in an open and welcoming direction (Peterson & Kern, 1996).

More in line with the predictions, the results obtained relative to the technological level indicate that, on average and other factors remaining constant, countries with a higher level of technological sophistication tend to have a higher demand for art house films.

5ConclusionsThe present study bridges previous literature on cultural consumption with the economic determinants of demand, by taking into account individual factors, such as experiential motivation and taste, with industry and social-structural factors. We thus contribute to a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of film demand, especially as an art form.

Support was found for the general principle that cinema tastes can diverge into different patterns across countries. Thus, the film patterns constructed here can be regarded as carrying certain elements of social reproduction, which means that some countries are more exclusive in their attitude towards mainstream films, while others look at films as art work.

However, in most modern societies, no art floats free of economic ties and regardless of the motivation to see a movie, all cinema-goers are looking for quality (Holbrook, 1999). Accordingly to our research, the higher quality of domestic films (proxied by the films’ average budgets) is positively associated with the relative demand for such films.

Cinema films are experience goods, and this ‘art’ or ‘entertainment’ experience is more marketing-driven than manufactured goods.

Thus, in terms of managerial implications, our results evidence that if larger audiences for art house films is to be desired, filmmakers have to forge new links with the audience based on storytelling, enabling them to reach beyond the basic definitions of world cinema, art house or foreign language films as blanket genres. Filmmakers, producers and marketers must have an understanding of the different film audiences, must discover how to engage them, and how to position the film appropriately by setting expectations in relation to its genre, style and aesthetics. It is important to connect ‘the right movie’ to ‘the right moviegoer’.

Steeply rising costs in film production mean that even domestic films that hinge on state subsidies must be able to attract an audience of a certain size to survive (Squire, 2004), and as in most industries, selling a film without marketing is a difficult if not impossible task. Indeed, in our study, marketing investments emerged as a key determinant for the consumption of art house films. This means that larger marketing budgets positively contribute to domestic film performance. Existing disparate evidence shows (e.g., Reinstein and Sneyder, 2005) that strong marketing campaigns are absolutely essential because consumers may seek signs of quality in advance of attending, such as good critical reviews, or other signs contained in advance publicity, marketing, and word-of-mouth from others who have already seen the movie. Therefore, some argue, to achieve that standing, the marketing process should begin as early as possible.

Our findings further suggest that structural factors, namely technological levels, play a significant role in creating stratified film consumption. As argued by Peterson and Berger (1975), cultural market cycles of innovation create an opportunity for competition and creativity when institutional barriers are lifted, and the global motion picture industry faces a revolution in the way films are conceived, produced and distributed. The advent of the digital era affects almost all sectors of the global value chain. The existing literature argues that access to screens for domestic films is a key problem, underlining the importance of forging state policies promoting more rapid screen digitization so as to ensure that there is a space for less commercial productions (i.e., art house films). In this line of reasoning, technological sophistication and relative demand for art house films emerge as intimately related.

Notwithstanding some contributions to the existing literature that the present study has provided – cross-country, quantitative and multivariable analysis of the relative demand for art house films – it does have several limitations and caveats. Firstly, we acknowledge some degree of arbitrariness when setting the threshold reference ratio for the dependent (dummy) variable. However, we try to mitigate this potential pitfall by considering two different thresholds (10% and 20%) and justifying their rationality. Secondly, our framework did not test for the importance of screens by type of film. Although we made every effort to find this information, there is presently a lack of data for eight countries in our sample, which hampered the inclusion of this variable in the multivariate estimation. Thirdly, interesting film industries in countries such as India and Nigeria had be excluded from this study as it was very difficult to obtain reliable and comprehensive industrial data.

To sum up, all the caveats and limitations pointed out above reinforce the need for additional and comprehensive research regarding the demand for art house versus mainstream films based on data from multiple periods, multiple countries, and multiple ways of operating the key constructs of interest.

Rigorous studies and comparisons of domestic film industries spanning the commercial to the state-subsidized, the small-scale to the large-scale, and the integrated to the disintegrated, are in demand. In order to begin to understand global linkages between people and places, and the emergence of new, global practices and networks that may ultimately change the known patterns of specialization and organization of the film industry, it is necessary to take the growing global diversity of countries within the film industry seriously.

It is important to acknowledge however that this proxy is rather weak and can be somewhat restrictive in the ‘art house’ films demand.

For example, the controversy surrounding the national identity of the film A Very Long Engagement/Un long dimanche de fiançalles (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 2004), which prevented it from competing at both the Academy Awards and Cannes, hinged on the film's financing from a French subsidiary of Warner Bros (Cook, 2007).

In the German case, the list of released films used was taken from the Box Office Mojo International at www.boxofficemojo.com.

Since this data is not available (with some residual exceptions), first, we contacted the film institutions, which were in a few cases able to provide this information. In a second stage, an email was sent requesting the figures on the average marketing cost per film (P&A), and we contacted (274) film distributors that had distributed a domestic film in 2007 or in an adjacent year, in order to collect the missing data. This attempt was not very fruitful because many refused to give “confidential” and “market sensitive” information. In the subsequent contacts made, we stated that the data were confidential and for academic purposes only. Although the collected data is reliable and provided by direct sources, it is important to note that most distributors were reluctant to share these figures and did not want to be quoted; therefore, they cannot be used as ‘official’ sources.

The cultural and creative employment data was gathered from the European Cluster Observatory, the Australian Report Card, WIPO Survey 2003 and 2004, Nzier Report, 2006 Japanese Establishment and Enterprise Census, and KOSIS.

This latter group includes countries such as Sweden, Poland, Denmark, United Kingdom, Italy, Czech Republic, Turkey, France, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. Beside the countries mentioned, Hungary, Spain, The Netherlands, Norway, Germany, Finland, and Greece are also place above 10%. Countries that present a ratio art-house versus mainstream films below 10% include (by increasing order of the ratio) Luxembourg, Slovak Republic, Austria, New Zealand, Portugal, Canada, Australia, Ireland, Switzerland, Belgium, Mexico, and Iceland.

The data from UNESCO (Institute of Statistic) relative to the percentage of Gross Box Office of all films feature exhibited that are domestic can be downloaded in http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=5538 (accessed January 2014).

Hosmer and Lemeshow (1989) proposed a statistic that they show, through simulation, is distributed as Chi-square when there is no replication in any of the subpopulations. This test is only available for binary response models. The Hosmer and Lemeshow Test table provides a formal test for whether the predicted probabilities for a covariate match the observed probabilities – a large p value indicates a good match. A small p value indicates a poor match, which means that alternative ways should be found to describe the relationship between this covariate and the outcome variable. Regarding the logit model, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test as a null hypothesis corroborates the statement that the model represents reality well.