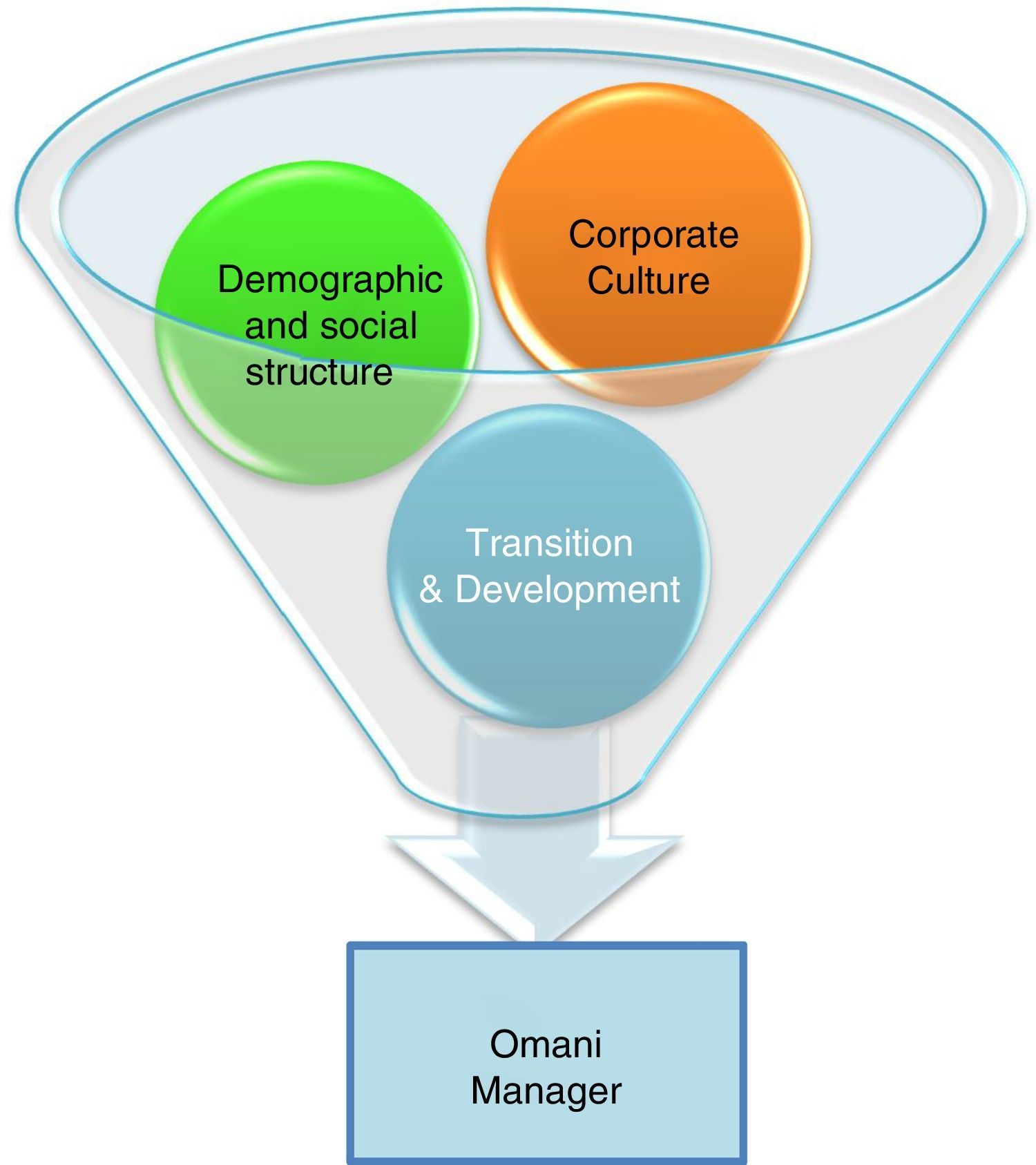

Transition management seeks to guide the gradual, continuous transition process of socio-political practices and steer the outcome of change to reduce the uncertainty as well as produce desirable social outcomes and enhance resilience during the transformation. Omani managers are in the phase of transition as Oman is going through transformation and change in all its sectors which pose many challenges facing those concerned with the management profession. The purpose of this paper is to address such transition by focusing on management development knowledge with special reference to images of managerial professionalism and the tension that may arise due to cultural issues. It also highlights on the importance of planning in the process of transition and change. Twenty managers from various sectors in Oman were interviewed between 2015 and 2016. The outcome revealed how Omani managers are in line with the changes and transition, within the framework of the national and organization's culture that focuses on social and interpersonal aspects in decision-making and relationships at work. What influences management and change process in Oman is the Omani subcultures and their backgrounds but they all agree that change is a vital element that needs to be taken into consideration and culture plays a powerful role in the process.

Management practice in Oman has been undergoing a major metamorphosis over the past few years. One cannot oversee the fact that rapid change has marked our civilization, knowledge as the basis of a new world economy, globalization, as a dominant international trend, instant world community through split-second communications and market fragmentations Something of a paradigm shift in favor of professionalism seems to have swept through the management community. At the heart of the new professional ethos is the recognition of the need for the quality of the managerial know-how along lines once compatible with the international state-of-the-art and sensitive to the socio-cultural context of Oman. This two-pronged quest is clearly reflected in this study highlighting specific barriers and the transition into an organizational society.

Loorbach (2010, p. 166) defines transition management as: “analytically based on the concept of transition as multilevel, multiphase processes of structured change in societal systems.” Transition involves many aspects, as such the role of human resources manager has changed and shifted over the years with an indication of the shift toward a strategic champion role. This in turn effects the organization in the form of training and development programs, rewards, etc. Other changes have been noticeable in terms of employment, growth of direct communication with the workforce such as team briefings and meetings between senior managers and the workforce and that is perhaps the clearest trend (Loorbach, 2010).

Another trend is experimentation with new management practices. according to Loorbach (2010) four main areas of activity: appraisal and reward, involvement and participation, training and development and status and security. The author indicates that those practices are not new but are associated with change. Management development is part of the transition practices taken from Western theories, various approaches and philosophies used have all been under some changes. Management literature has recently acquired renewed interest in the conventional concept of ‘organizational climate’ under the label of ‘corporate culture’. This concept has been on the rise since the 1970s. The term generally refers to corporate ethos, partly designed and partly spontaneous, which bestows meaning and purpose on organizational membership and shapes management practice in specific ways. It is an invisible but highly potent force that ties members together as a cohesive body in the pursuit of shared goals. It is true to say that an average Omani manager relies heavily on highly personalized and informal methods and styles in the management of his organization. However, members of the young generation realize the fact that some of the experience, attitudes and beliefs, which their elders hold, are not always reliable or adequate for them in their effort to shape the future.

This paper investigates the management culture in transition, an attempt to better understand the present position and future prospects of the Omani managers and the role of development in changing the current culture to be in line with Oman's 2040 vision. This was fulfilled by interviewing managers from various sectors in Oman. Twenty managers were interviewed between 2015 and 2016. Focusing on images of managerial professionalism and its major issues and influence on the transferability of managerial know-how, taking into consideration the Omani development plan that focuses on economic diversification, industrialization, privatization, and foreign investment with the objective of reducing the economic dependency on the oil sector, being in line with Oman's 2040 vision.

1.1Aim of the researchThe purpose of this paper is to address the issues underlying management profession in Oman and changes and transition that has taken place and is still ongoing. Since the researcher is living and working in Oman, she found it interesting to explore the changes and development that has taken place in Oman. The paper also seeks to investigate the role of culture in the process of such transition and challenges that face Omani managers with more accurate understanding of the forces and constraints relevant to the making of young management professional (Fig. 1).

2Literature review2.1Culture and corporate cultureContemporary definitions of culture looks at the notion of culture in terms of shared phenomena among members of a group with a common language, in a particular geographic region, during a specific historic period (Triandis, 1996). Morgan (1997) views culture as particular events, actions, objects and situations that are carried out in a unique way. According to Schein (2010), demands, expectations, and constraints originate from and are shaped by socio-cultural values, norms and mores, which have roots in a long history of traditions, religion, and popular belief systems. Hofstede (1980, p. 43) defines culture as “the collective mental programming of the people in an environment. Culture is a powerful socializing agent affecting not only members’ perception of the world but their self-image as well (Hofstede, 1984, 2013).

Hofstede (1980, p. 45) describes national culture as “the common elements within each nation – the national norm – but we are not describing individuals.” Most businessmen in the West, for example, regard acquaintance and discussion periods as opportunities in which they try to make their points quickly and efficiently. In the Far East and certain European countries there are reservations against such quick business meetings (Muna & Zennie, 2010; Harris & Moran, 1983). Looking at culture at the national level, there are some ‘silent’ languages of culture that adds on such as context, time and space. Hofstede (2013) identify low-context cultures and high-context cultures. In the former, most of the communication takes place through written or spoken. However in the latter, things are different, where written and spoken are part of the communication or message and body language, physical setting and past relationships are considered as important and complete the communication process.

Culture in the Gulf States is influenced by religion and historical factors, with each aspect of their life depending on one another (AlHashemi, 1996; Harris & Moran, 1983). Muna and Zennie (2010) indicates how the social structure of the Gulf region has certain distinctive characteristics that tend to dominate managerial thinking and behavior. Omani culture does not have a caste system, but it does operate in a hierarchy based on family connections (tribal ties), relative wealth, and religious education. At the top of the pyramid is the sultan and his immediate family, the Al-Sa’id (AlIsmaily, 2004, 2006). A large tribal group, the Al-Bu Sa’id, follows this. Prior to the discovery of oil, the wealthiest group (class) was made up of the merchant families, many of them Indian in origin, language, and culture. Certain families and tribes had built reputations for religious learning and mediation skills, and they often represented the government in the interior of the country. In the late twentieth century, wealth spread somewhat and a few more Omani families joined the ranks of the extremely wealthy. Oman has a small but growing middle class while the vast majority of its population outside.

The organization's culture is a way of reflecting the identity and personality of the organization and has an influence over shaping the behavior of employees working in that culture (Moran, Harris, & Moran, 2011). Organizational culture is described as the feelings and impression that one gets when entering an organization, giving the impression of how it feels to work in that organization (Moran et al., 2011). It therefore includes: beliefs, behavioral patterns, habits, customs, the friendliness of the staff, the layout and surroundings, ceremonies, rituals and traditions that members of the organization hold in common as they relate to each other and become accepted and standardized in a particular group, attempting to meet their continuing needs (Morgan, 1997; Moran et al., 2011; Schein, 2010).

In brief a corporate culture is a generally invisible but highly potent bond that ties members together as a cohesive body in the pursuit of institutional goals. It is a powerful socializing agent affecting not only members’ perception of the world but their self-image as well. A national management culture is in many ways a reflection of the overall general culture. In some cases particularly Japan, it is a mere extension of the general culture with apparently no visible tension between the two. In other cases this element of tension can be felt as the emerging management culture starts to challenge some of the more conventional more of the traditional system. The rift is particularly accentuated by the fact that some cultures are more organizational than others, in the modern sense of the term. The fact that the organizational phenomenon is deeper rooted in Western Industrial societies, is hardly surprising. Those societies have had a longer period during which to assimilate the changes resulting from transformation leading to greater dependence on organization. In such societies, the management culture gradually came to dominate the general culture and shape its complex fabric.

The developing societies are still cultures in transition with visible tension between the traditional modes of behavior, and the recently acquired corporate ethos. They provide striking examples of dualism: cultural, economic, and organizational.

2.2Demographic distribution and social structure in OmanOmanis, being part of the larger Arab world, have some common values that are shared by their other Arab cousins (AlIsmaily, 2006). The Omani national identity has evolved from its predominant Arab language and culture, its tribal organization, and Islam. Most Omanis belong to a sect known as the Ibadi, and all the sects within live and work alongside Christians, Jews and foreigners. Ethnic, sectarian, or linguistic conflict rarely occurs in Oman although tribal disputes are not unknown (AlIsmaily, 2006). The Omanis’ history dates back thousands of years before Christ, and in many ways have held on to their ancient traditions. When oil was discovered in Oman around the 1970s, many aspects in Oman changed, new wealth for the people, better infrastructure and Oman was modernized (AlIsmaily, 2004, 2006). According to a report published by World Health Organization (WHO, 2010), Oman has progressed well toward achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), especially in reaching near universal education (including gender equality), as well as various health concerns. With a population of 4,500,290 million as of Sep 2016 (http://www.omaninfo.om/english/index.php), 62% are males and the rest are females. Non-Omanis constitute 45.6% of the total population. The population is growing rapidly at present and is becoming increasingly urbanized. With projects undergoing and rural areas being built up, affecting demographic distribution. The structure places increasing demands on education, provision of welfare services and increasingly on employment.

The extended family is powerful enough to reflect themselves both in its institutions and the interpersonal relationships of its embers. Thus the social structure that will be referred to in this paper covers patterns of relationships between members of society as these relationships manifest themselves in institutions, groups, norms, mores and roles. This implies that an average Omani manager relies heavily on highly personalized and informal methods and styles in the management of his organization. However, members of the young generation realize the fact that some of the experience, attitudes and beliefs that their elders hold are not always reliable or adequate for them in their effort to shape the future. They feel that the alternatives from which they have to choose are more varied and complex than those their elders faced, and realize that they have to earn new ways and develop new guidelines for dealing with them.

3MethodologyQualitative methodology was used to fulfill the purpose of this paper. Twenty managers were selected from various sectors in Muscat and Dhufar including: oil, petrochemicals, telecommunications, government, and educational institutions were interviewed. The levels of managers ranged from executives, to heads of departments or units to supervisors. Experiences ranged from minimum 5 years to over 15 years. Structured interviews were conducted aiming at investigating the role and characteristics of Omani managers and in insight into the managerial styles used, role of Omani managers in light of the transition that is taking place, and the challenges facing Omani managers. A survey was also used to look at the composite profile of Omani managers. Most of the interviews were recorded and then transcribed, however few of the managers opted not to be recorded and a normal interview took place.

It is the writer's belief that emphasis on the qualitative approach will help to provide focus on explanation through developing understanding rather than through predictive testing. And an emphasis based on and inductively developed from data rather than on a priori deductive theory. Qualitative approaches lend themselves better to the emergence of unanticipated findings and are in many cases broader and more realistic in perspective than purely quantitative tools. As such this will assist to focus on a discovery-oriented investigation full of meaning, validity, richness and meaningfulness of data. Also, the researcher is able to gain insight into feelings and emotions of the managers which adds further information and captures additional dimensions that is not reflected in the quantitative method.

4Interview analysisTo investigate various aspects and dimensions in Oman's culture, interviews with twenty managers from various sectors were carried out between 2015 and 2016. The majority of the managers interviewed referred to the manager's need for social acceptance centers related to specific expectations, constraints or demands which society places on individuals. Social pressure refers here to the expectations, constraints or demands which society places on the individuals. Such influences originate from and are shaped by socio-cultural values, norms and have their roots in a long history of tradition, religion and popular belief systems. Other pressures from the business and social community include: (a) difficulty in separating business affairs from social or personal life, that is, inability to compartmentalize social life, business life and personal life; (b) risking face and image and reputation in the community in particular family reputation which is at stake by not conforming to norms and expectations; (c) frequent inability to escape the insistence of clients, citizens, employers and government to deal only with the head of the organization; that is the feeling that only the top man of an organization can get things done; (d) social visits during working hours at the office. This phenomenon is closely related to variables such as value of time, social and business life; (e) high expectations for success from family, colleagues, supervisors and public officials.

The examination of social pressures leads us to the important question of what specific behavior or role is expected of these managers while focusing on the manager as a target of social influence and control i.e. the role in the community and an organizational leader as the agent of influence and control.

4.1Organizational role symbolsA manager is primarily considered as a decision-maker; a leader; a person who is responsible for the profitability and growth of the organization and various other functions and duties relating to the efficient utilization of resources (Mintzberg, 2009). Omanis were exposed to different cultures, those that were from Zanzibar society and those that shifted from outside the country and settled in Oman. There are also those who were exposed to ventures abroad. With such different cultural background, it is possible that managers may function differently (AlIsmaily, 2006). In many private businesses, managers perceive their role as heads of an extended family. In addition to the usual demands for increased wages, better working conditions or promotion, the manager is often under the pressure to help employees with their personal or family difficulties. Equally employees expect to be treated well by their manager and the organization.

On the other hand, Omani managers face challenges of globalization and changes, therefore they had to change their role in the society and in their organization (AlHashemi, 2013). The managers in the interview pointed out that Omanis, being part of the larger Arab world, share some common values by their Arab cousins, yet they also possess socio-cultural characteristics that are unique to Omanis only.

In all, the style of management followed by Omani managers depends on the following factors: size and nature of the organization, educational background of the managers and where they were educated whether in Oman or abroad, the experiences of the managers and their exposure. However, many of the managers interviewed, they stated that the role of the manager in Oman and the Gulf Region is changing rapidly and is moving toward fostering a stronger work ethic discipline, productivity, better time management, accuracy and precision, technical know-how and competence while continuing to operate effectively within the existing social fabric. When asked whether the Omani managers follow an open door policy, 50% of them said yes and the rest indicated that it is followed but at a small percentage and depending on the nature of the organization. One of the managers indicated: “I do try to follow the open door policy and allow employees to come and share their concerns.”

4.2Managers in the local communityThe community includes the manager's friends, extended family, government officials, and business associates. Community role expectations generate specific activities managers have to carry out. With each role there usually is a pattern of reciprocal obligations and claims. The kind of reciprocity indicated here implies exchange relationships in which players in the social game are often mutually dependent on one another (Hofstede, 1991, 2013). The extended family still plays an important role in spite of the economic development and modernization that has taken place in the Gulf area (AlHashemi, 2006; AlIsmaily, 2006).

According to the managers who took part in the interview, the Omani manager lives and works in a society whose social structure, with all its diversity, has some distinctive features, which have considerable impact on him. It is a society where family and friendship ties are dominant even in the functioning of formal institutions and groups; hence reliance upon family and friendship ties for getting things done within society and organizations. The examination of local social pressures coupled with cross-cultural tensions lead us to the important question of what specific behavior or role is expected of Omani managers as organizational leaders and agents of change (AlHashemi, 2013). They characterized the Omani managers as being loyal honest, hardworking, support team work, flexible, responsive, open to learning and educating themselves, intuitive and respond to changes around them. Some of the managers interviewed pointed out that these characteristics depend on the nature of the organization as well as the position the manager holds, as some managers may have the authority but do not exercise full practice due to lack of awareness or fear of losing their position. From the interview, the author found that Omani managers are exposed to different education and experiences, (30%) have been educated and trained outside Oman in UK and USA, and they have a different perspective and style than those who were not exposed to such experiences. This is also in line with and supports studies conducted by AlIsmaily (2006) who indicated tribal-family relations and religion reflect other aspects of management; they prefer flexibility but are by no means risk takers.

4.3Group dynamicsThe managers interviewed stressed the preference for a person-oriented approach is one of the characteristics of Gulf management is the obvious. There seems to be a strong aversion to impersonal relationships when conducting business. In the Gulf area including Oman preference for personal ties and connections is evident in a wide range of activities. This has become an important and necessary means of doing business. They also expressed how time and effort will be minimized if the manager used his personal ties ad connections instead of the formal channels. This feeling is partly due to inefficiency of institutional procedures and the importance of family and friendship ties as effective substitutes (AlHashemi, 1987, 2006; AlIsmaily, 2006). By virtue of the position of the manager in the community and in the organization, he is expected to wield his power to influence the course of events in favor of friends or relatives. This practice can be detrimental to managers who do not have powerful connections as well as to those who do.

The other aspect of interpersonal relationships, as pointed out by the managers, is the use of social mannerisms and amenities in conducting business and cementing managerial transactions, as one of the managers expressed: “In our culture we tend to address social issues and personal ties and we are proud of that.” Another manager talked about a personal story where he risked his position to empathize with one of the employees. It is generally regarded impolite to start immediately with a formal discussion. Reasons given for this phenomenon are getting to know the other side on a person-to-person basis, to evaluate the person, to establish trust, to build relations, and to break the tension and put the parties involved at ease (Wilkins, 2001).

Western management thinking has been predicted since its inception on certain assumptions that might be very difficult to apply in Oman and the Gulf Region. Some of these assumptions relate to the organization as an impersonal network of roles, rules and standardized procedures with little room for any personal recognition. The majority of Arab managers tend to dislike impersonal and transient relationships in the work environment (Hofstede, 1991, 2013; AlIsmaily, 2004, 2006).

Although other Western management theories of the behavioral bent tried to argue the need for a ‘human side of enterprise,’ their attempt never quite managed to replace the lingering image of the organization as a machine geared to the attainment of maximum feasible efficiency (Weir, 2001, 2004). The theme of impersonality and assignment of priority to the job not the incumbent continues to dominate formal organizational thinking today. This has brought varied reactions ranging from acceptance and resignation to ambivalence, rejection and alienation. It is not insignificant to note that such a frame of reference is strange to the personalized management culture in the Gulf. The relevance of this issue to the preparation of management is obvious. The challenge is to design programs that prepare future managers for a level of performance that measure up to international standards but within the cultural constraints of Oman.

4.4How managers decideDecision-making has continued to occupy management theorists and practitioners alike as a dynamic process of choice among alternatives (Mintzberg, 2013; Stewart, 1999). Perhaps a fair measure of the importance attached to decision making in the literature is the fact that it cuts across all the major schools and approaches from classical to modern and from behavioral to quantitative. Styles is also treated at length with due regard to trade-offs and implications affecting both the individual and the organization. The extent to which a manager or an executive in the Arabian Gulf shares his power of decision making with his subordinates under various conditions is partly shaped by broader socio-cultural, economic and psychological influence coming from the environment (Ali, 1990). There are also expectations among some senior managers, partners, friends and relatives to be consulted. It is as well the practice of some managers to prefer individual consultation with each subordinate thereby, de facto, avoiding majority decision. Consultation for some managers seems to be an effective human relations technique.

In Oman, some of the managers interviewed follow a systematic way when it comes to taking decisions, taking certain steps starting with laying out plans and studying various scenarios and then consulting among each other to take the final decision. There are also historical roots for consultation where tribal leaders have practiced for millennia. Consultation for some managers seems to be an effective human relations technique. It is used to please, to win over and to placate persons who might be potential obstacles and to avoid potential conflict. In government institutions, decision-making is perhaps at a slower pace, but in general, managers take the change process gradually and step-by-step being in line with the overall government approach. Some managers faced resistance from employees as they were not fully aware of the change process-taking place in the country and were comfortable with their own styles and traditional methods. This also applies to some of the managers in senior and lower level management, where preference was given to their style and system. However, other managers found ways to overcome this problem through giving more authority and responsibility to first line managers and they see this as an approach they will be following if they want continued changes in the future. Some of the managers in the interview (40%) pointed out that the dominance of the one-man syndrome in dealing with organization matters exists in very few organizations in the Sultanate, perhaps in the government sector.

The majority of the managers (80%) use the consultative style especially when they are faced with situations or problems that they need to consult others in order to make effective decisions. Informality is a common factor that the managers shared when asked, using informal relations to get things done, or in dealing with employees and other managers whether in their organizations or outside. “Whenever I face a situation or a problem, I would call my assistant and some of the employees and put forward the issue and try to involve them and get consultation from them before I make the final decision.” Few of the managers interviewed (20%) were exposed to experiences outside Oman, therefore they tend to integrate their outside experience with their current style. However, the managers expressed concern on the transferability of Western management philosophy and methodology and pointed out that attempts to transfer successful system from one country to another had failed due to social, cultural and other incompatibilities. These results are in line with AlHashemi's (2013) study where a group of 55 managers took part in a study to explore the challenges that face Omani managers.

4.5Time managementOne of the difficulties facing managers in the Gulf Area, and Oman is no exception, is the lack of appreciation toward time shown by some of the people with whom they come in contact. Though most managers and executives would claim that they value time highly, it is observed that such responses are only nominal and formalistic as they are not necessarily indicative of actual behavior. Some of the reasons which inhibit appropriate utilization of time include: a range of social pressures and constraints, social visits at the office, the top-man syndrome; inadequacy of the organizational infrastructure, poor communication, human resources, excessive bureaucracy, poor delegation, and the manager's employee-oriented interpersonal style.

Some of the managers in the interview (40%) raised the concerns of timing in terms of one of the challenges facing Omani managers especially in the education sector, in particular the start and end of each working day. However, according to one of the female executives in one of the government institutions, she stressed there is high appreciation toward time in Oman, especially in organizations that are undergoing change. This appreciation is in terms of meeting deadlines and targets.

4.6Perception of changeChange has been overwhelming in the Gulf States fueled by the increase in wealth, the transformation in the infrastructure. Hayes (2014) indicates that effective leaders are those who set a direction for change and influence other to achieve goals that improve internal and external alignment. Industrialization and modernization are superimposed on the same traditional, socio-cultural system. Such a process is bound to create some tension between the old and the new. It has been argued that the modern and traditional can and do co-exist in what is called the ‘prismatic society’; a society no longer totally traditional but not Western either. Others have shown that tradition and modernity can be mutually reinforcing rather than conflicting. Ali (1993) points out that in the Arab world, any approach to organizational change is assumed influenced by existing work ethics and norms.

A major question to ponder is the specific mix of the traditional and the modern at different stages in the transition process. While environmental forces will mostly determine the nature of such ‘mix’, the role of management in this process must not be underestimated. It can be argued that that a manager is still in a position to influence the composition and the ingredients that make up the balance of the modern and the traditional. The manager is in a position to introduce change to society particularly through his professional outlook.

Oman's transformation took place gradually in all the sectors in the country. The implementation of the US-Oman free Trade Agreement (FTA) in January 2009, paved the way for more development and opportunities for further investment in the country (US Department of State, 2013). With privatization taking place in Oman, it has altered changes in some practices within the transformed organizations (Wilkins, 2001). In 2011, the government amended legislation to allow for public–private partnerships in government hospitals and clinics as well as other sectors such as telecommunication and electricity. The most successful privatization program to-date is perhaps the electricity and desalination privatization program (US Department of State, 2013).

Omani managers perceive change as a vital element especially that the country is going through major transformation and transition. During the transition, managers witnessed some resistance and reactions from employees and this was handled by careful planning, extensive training in all sectors, collaboration between various organizations, and support from top management. What influenced management and the change process in Oman is the strength of subcultures from various origins and the increase of women in the workforce.

4.7Managing transitionManagers interviewed showed equal awareness of the fact that the construct of leadership and managerial professionalism permeate organizations from within in so far as they influence the behavior of the individual managers. Whatever impact these constructs have can be sustained to the extent that it is internalized by individuals in their actions. Thus leadership was pointed out as a highly needed managerial quality exhibited by change agents and organizational innovations. Perhaps the strong sense of Omani managers of the transition that seems to have swept them partly explains the high premium they place on leadership. Many of the manager interviewed indicated that a through understanding of what stimulated Omani managers is a fundamental prerequisite for attaining the desired levels of managerial professionalism through accelerated management development. It is equally striking to see how truly concerned the managers were with the issues of managerial professionalism.

With regard to the issues of transition and change, according to one of the executives in Oman, who stated that what has helped in this process is the recruitment of fresh graduates in new organizations or in organizations that are going through change and transition. He emphasized that they are trained to adapt and fit within the culture in the organization. This transition has already taken place in some of the organizations in Oman such as telecommunication, education and some of the ministries. However, in some organizations the change was gradual and therefore not sufficient transition has taken place. On the other hand, according to some of the Omani managers who stated that a well laid out plan was developed in the beginning of the change process that involved training and developing of the employees to prepare them for present and future. They see management development as a vehicle for accelerating the professionalization of management practice in Oman and basing it on a specialized body of knowledge and skills at once universal and yet sensitive to the cultural particularities of Oman.

5Concluding remarks and recommendationsIn this paper an attempt was made to sketch out a profile of an Omani manager against a changing background and an environment in transition pursuing cultural, organizational and inter-personal levels. It was pointed out how socio-cultural values operating through the social structure, institutions, groups roles and social networks influence the attitude of managers. An attempt was also made to underscore the role and the importance of a manager as a leader and as a change agent critical to the survival and future development of the country which in turn calls for devising and launching appropriate management development programs. A clearer and more representative picture is called for. Invariably the priorities, problems, means, constraints and promises of management development in Oman are most closely felt and experienced by the managers themselves.

Transition management refers to the people side of the process: what you, your staff, or your partners in business must go through to let go of the old, moving from the old to the new, ensuring a successful new beginning. Transition looks into people and how they respond to the actual change event, and is considered as highly personal (Loorbach, 2010). Oman is in the process of change and development at the moment, with projects undergoing such as the expansion in the airport, resorts, educational institutions and other services in the country. This entails utilizing various tools to help in this transition, training of human resources in all the sectors in the country. Oman is actively seeking foreign investment and is in the process of improving the framework to encourage such investments. It is significant to remember that what seemed far removed and speculative to the eyes of an outside observer, suddenly assumes a new urgency when approached from the vantage point of managers themselves.

In a nutshell, Oman is currently undergoing a multi-pronged metamorphosis toward an organizational society. The country is pursuing a development plan that focuses on economic diversification, industrialization, privatization and foreign investments with the investment with the objective of reducing economic dependency on the oil sector. Vision 2040 focuses on human resources development; therefore, it is going through gradual change and transition in most of its sectors.

Transitions are seldom smooth and never easy and Omani managers today find themselves facing significant crossroads whereby they are to part with old ways before having fully chartered the new waters they have to sail. That a certain degree of experimentalism is to be expected under the circumstances is beyond dispute. For such experimentalism however, to yield the desired learning dividend, managers have to push forward with the already discernible drive for managerial professionalism. Omani managers skilfully learned to couch decisions and actions in styles that are not threatening to established cultural norms in order to facilitate goal achievement and accelerate change. Major accomplishments have already been made in this direction and there is a campaign for public awareness that has started taking place to make people aware of change in the country, work ethics and many other aspects. Despite the economic downturn in the region, it is considered as vital to prepare and train managers to be able to handle transition and change in the future. There have been major cut backs by some of the organizations, but training and developing managers should not be part of the cut back due to its importance and role for future development and to be in line with the country's 2040 vision.

In light of the above, future research can be carried out further by investigating a larger sample of organizations in Oman and other Gulf countries to explore lessons learned and to make comparisons on the critical issues raised in this paper and other factors such as: team work, cultural diversity, challenges facing local managers and future prospects for management development. Also, gender can be investigated in more depth by examining the role of women managers in Oman. The challenges facing them and the impact of change they may have on the economy as a whole.

It is important to bear in mind engagement-oriented and process-focused approach to the management of organizational change that is going through transition to insure better collaboration between leaders, managers and other employees. It should be borne in mind that, first of all management development is a joint venture involving managers themselves, government, and centers of management education and training. None of these parties can accomplish the task unilaterally and none should. Oman's experience suggests that management development has to be approached at three interrelated levels (macro, intermediate and micro) to have an enduring effect. The second observation is that incrementalist, atomistic, piecemeal approaches to management development will not meet the challenges. Integration represents a fundamental requirement for success. Integration entails building inter-organizational bridges so that institutional experiences may be shared and collective intelligence may be developed.

Perhaps one of the most far-reaching implications of Oman management development experience is the already visible trend toward professionalizing management practice. A higher degree of managerial professionalism will also lead at once to greater sensitivity to local environmental particularities and better integration into the international professional set up.

There are a number of steps that should be taken into consideration to manage transition from the old and existing structure to the new organizational set up. This means undertaking participative leadership, systems thinking, empowerment and the change process. The following are key elements of the process:

- -

Timing: the timing is the foremost important element in beginning of the transition process. In organizations in Oman, targets and deadlines were set and people are dedicated to meeting such deadlines.

- -

Preparing employees: gaining buy-in from employees at all levels of the organization is very important, as it would enable the success in a transition. Regular input is needed from employees along with their ideas as well as allowing them to participate in planning and perhaps decision-making. Issues to be addressed should include: The encouragement of the development of more participative leadership practices in traditionally hierarchically structured organizations; the engagement of all staff in a visioning process and encouraging their participation, understanding of, contribution to future goals, and, the establishment of internal change agent groups where possible who will be in a position to facilitate communication process between management and other employees.

Reflecting on the author's organization, one effective method used by the College is through regular emails from the Dean's office to the College requesting input and feedback from staff members. Employees were also briefed from time to time on the progress and outcome as well as future plans. The college thus took into consideration foundational elements to insure high staff involvement and initiatives; sharing appropriate decision-making responsibilities and power in line with the circumstances.

- -

Planning and implementation: Planning helps organizations chart a course of actions for the achievement of their goals. The process begins by with reviewing the current position and operations of the organization and identifying what needs to be carried out to improve operations or to move from status qua to the desired outcome.

It involves envisioning the results of the organization wishes to achieve, and specifying the steps necessary to arrive the intended success. Thus it is important that formal and careful plans are prepared by establishing goals taking into consideration the management of risk and uncertainty, efficient use of resource, team building and creating a competitive advantage by moving from the old structure to the new. Physical workplaces and work groups should be planned for, duties and responsibilities of employees should be clearly defined.

In terms of planning as far as the author's organization is concerned, new buildings were established, programs were added as well as supporting facilities. Some of the departments in the organization were shifted to a new building, with different a completely different physical layout than the previous one as well as reassigning responsibilities to the staff. This shift took place in October 2013 and the transition is still on going.

Monitoring: Monitoring is the routine and systematic collection of information against the plan established by the organization. It should be systematic and purposeful. Monitoring can provide information that be useful in: ensuring activities are on track and carried out to the standard required, identifying difficulties and problems facing the project, analysing the situation in the community, determining the efficiency and the effectiveness of the resources utilized for the plan. Feedback mechanisms should be in place during and after implementing the transition. Consider the project as a work-in-progress rather than viewing it as a finished project. Feedback from employees and management is essential to fine-tune and alter specific aspects of the new structure (Ingram, 2013).

Looking at the author's experience, the restructuring that is taking place at her organization as whole and the College in particular, is an on-going process, feedback is continuously being requested from faculty members, and sub-committees created to tackle more specific problems and concerns.