Employees play an important role in the public procurement of innovation (PPI). Based on institutional theory, this study aims to determine how specific institutional factors and various endogenous institutions can impact the use of an innovation by the employees of a public organization. The institutional factors come from the theories on the types of organizational culture developed by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) and from the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) (George, Hall, & Stiegelbauer, 2006; Hall, Dirksen, & George, 2006). These theories were applied to Olympic, a former national airline. Data were collected using a questionnaire (N=102), and multiple regression analysis was then used to statistically analyze the data. The study's findings showed that (a) increased employee interest in an innovation, (b) organizational cultures characterized by high sociability and high solidarity, and (c) active employee participation in the introduction of an innovation positively affected subsequent employee use of the innovation.

The key role of employees in the successful introduction of innovations makes them a crucial element of the PPI process. Innovations afford public organizations a competitive advantage and result in benefits for citizens (Bugge, Hauknes, Bloch, & Slipersaeter, 2010) by improving efficiency and the quality of the services offered and contributing to economic growth (Bernal-Blay, 2014). The successful introduction of an innovation is, for the purposes of this study, defined as a problem-free introduction of an innovation and its widespread adoption by individual employees. Management should monitor and facilitate such broad acceptance and use of innovations by individuals, as this may help organizations achieve the projected outcomes of their introduction (Hall et al., 2006).

The introduction of an innovation affects both the overall operation and individual employees of an organization. Organizational culture plays a pivotal role in organizational operation (Alvesson, 2002), and an appropriate culture is essential to the successful introduction of an innovation. Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) proposed specific culture types that correspond to the particular circumstances organizations may face; these are useful to organizations that are introducing an innovation and require a new and facilitating culture.

Identifying the specific needs of the individuals involved in an innovation's introduction is very important for management (Choi & Price, 2005), as each person's individual attitudes and beliefs will result in different responses to and use of the innovation (George et al., 2006). To this end, the CBAM, with its three diagnostic dimensions/tools—Stages of Concern (SoC), Levels of Use (LoU), and Innovation Configurations (IC)—is useful. It can help management to identify, monitor and satisfy the needs of individuals, and it offers useful information regarding the current extent and quality of the innovation's implementation.

Studying the various institutions that exist within and outside an organization (endogenous and exogenous institutions) may, according to institutional theory (Rolfstam, 2012, 2013; Rolfstam, Phillips, & Bakker, 2011), help researchers and managers to better understand the behavior of employees regarding the introduction and use of an innovation. This study uses both Rogers's (2000) and Hommen and Rolfstam's (2009) interpretations of institutions and defines them as norms, rules, habits, corporate hierarchies, networks, associations, and committees. It focuses primarily on the endogenous institutions of the studied organization, as these seem to affect employee performance. Management of public organizations should identify all the relevant endogenous institutions, in order to reinforce those that positively influence employees in the adoption and use of an innovation and to negate those that hinder the process.

In the relevant literature, little attention has been given to lower endogenous institutional levels (Rolfstam, 2012, 2013). This article, therefore, adds a new element to the discussion by looking into the critical issues that prevail within the organization, in the vein of Rolfstam's (2012) article but with a novel approach focusing on those endogenous institutions that affected the use of an innovation.

This study aims to determine how specific institutional factors influenced the use of innovation by employees and contributed to the success of the PPI, based on the theory of the generic types of organizational culture proposed by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) and the CBAM's SoC and LoU tools (George et al., 2006; Hall et al., 2006). These theories were applied to Olympic—the former Greek national carrier—whose management decided to introduce a series of new technologies as part of a project to introduce innovation. Olympic had a number of particular characteristics, outlined in a separate chapter (Section 3), that made it well-suited as a case study.

The technologies—which were new to Olympic but they were well established in the airline industry—that Olympic introduced under the project were: a new Passengers Service System, which included a reservation system and e-ticketing; a pricing system; a Departure Control System; a corporate website and online booking engine; a Revenue Management System; and a Frequent Flyer System (Olympic Airlines, 2006). These technologies are primarily regarded as process innovations, because they increased the effectiveness and efficiency of Olympic's service provision process (Raasch & Hippel, 2013). Thus, the terms innovation and new technologies are used interchangeably in this study. Furthermore, the case of Olympic constitutes a case of public procurement because the organization was state-owned and the innovation was introduced with significant contribution from the government. The last via Ministry of Finance managed to have the approval of the European Union, as Olympic was under close inspection, and the necessary funds were made available to the management.

The following pages outline the relevant bibliography, present the organization chosen as a case study, describe the methodology used, and mention the statistical results. They then present the conclusions, the discussion on the institutional factors that affect the use of new technologies in this specific organization, the recommendations for future research, and the limitation of the study.

2Literature reviewThis chapter begins with a brief description of public procurement and institutional theory, followed by a presentation of the types of organizational culture proposed by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) and of the SoC and LoU as described by George et al. (2006) and Hall et al. (2006) respectively.

2.1Public procurement of innovation (PPI) and institutional theoryThe public sector plays an important role in the global economy: approximately 9% of the labor force in Korea, Japan, Greece, and Mexico is employed in government and public corporations, and this figure rises to almost 30% in Norway and Denmark, reflecting similar trends in government expenditures as a share of GDP (OECD, 2013). Public procurement is an important function of public organizations. It refers to the purchasing activities carried out by such organizations and can significantly stimulate innovation (Rolfstam, 2012). The state plays an important role in public procurement and should monitor the needs of public organizations and ensure good coordination between ministries and various authorities (Edler & Georghiou, 2007). There are various typologies—depending on the value of money considerations, the importance of the procured goods and services to the core mission, and their level of complexity—that a procurer may follow in order to successfully introduce an innovation (Uyarra & Flanagan, 2010). The literature review shows that an institutional approach can have a significant contribution to understanding the innovation process and employee behavior, especially when using the three modes suggested by Rolfstam (2012, 2013): multilevel institutional analysis, endogenous and exogenous institutions, and institutions as rationalities. Thus, there are multiple interconnected levels that are related to public procurement: the lowest of these is the organization or department that introduces an innovation, and above it are the various national and multinational bodies. Exogenous institutions are external to the organizations and departments that introduce an innovation and are imposed from above, allowing the latter little or no control over the process (e.g., legislation, regulations,), while endogenous institutions exist and evolve within organizations and may change as a result of learning and exogenous institutions. Actions in organizations are generated by the reactive responses of the various institutions. Every organization follows certain procedures for determining what actions must be taken in order to achieve its goals—this is called rationality; the actions and decisions of organizations can be influenced by political, legal, economic, and scientific rationalities.

All the factors above are intertwined and can affect employee behavior regarding the introduction of an innovation. According to Kingston and Caballero (2009) and Kondra and Hurst (2009), an important issue in institutional theory is the distinction between formal and informal rules or constraints. The term formal refers to rules that are explicit or written down, whereas informal rules are implicit and are not written down or are not enforced by the management of organizations. Moreover, informal constraints are not always clearly identified, and empirical work is needed to determine “how exactly the various kinds of informal constraints work, how they change, how quickly they change, and how they interact with formal rules in both a static and dynamic sense” (Kingston & Caballero, 2009, p. 23). Therefore, endogenous institutions and informal rules are not easily identified by management. In the relevant literature, more emphasis is placed on exogenous institutions (Rolfstam, 2012, 2013). Thus, the identification of the informal and formal endogenous institutions, which was the focus of this study, is important because they significantly affect the operation of organizations and influence the use of an innovation.

2.2Types of organizational cultureBy most definitions, organizational culture refers to the common characteristics, perceptions, values, beliefs, and fundamental principles that a group of employees follow in order to adjust to changing environmental conditions, and which contribute to intra-organizational integration and operation (Bourantas, 2007; Kondalkar, 2007; Schein, 2004).

In the relevant literature, there are various theories that group together organizational behaviors and propose certain generic types of organizational culture. The best known of these are Handy's (1981) theory and Quinn and Rohrbaugh's (1981,1983) ‘competing value framework.’ Another important theory is that developed by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003), which is the one chosen for this study. This specific theory provides valuable practical guidance for managers who wish to change their organization's culture (Buenger, 2000) and helps them to establish organizational cultures that facilitate the introduction of innovation.

Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) use the two key concepts of sociability and solidarity—as these exist amongst employees, within departments, and in organizations—to define four culture types. Sociability and solidarity can have high and low values, and the occurrence of such latter (i.e., low sociability, low solidarity) can signal problems for organizations.

According to Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003), environments with high sociability feature sincere mutual friendships and feelings of caring between employees, which can manifest within and outside the workplace. The main driving force behind decisions is emotion and social consideration. In environments with high sociability, formality between employees is minimized and hierarchical differences downplayed. Leaders are friendly, setting an example for geniality and kindness by caring for those in trouble. Management organizes special events and ceremonies to honor employees whose contribution in the introduction of an innovation is significant and to share information about project progress. Sociability exists among people who share similar ideas, values, personal stories, attitudes, and interests, and employee networks and teamwork thrive as a result. In such environments, workspaces are open and inviting in order to encourage communication.

On the other hand, in environments with low sociability, employees are mostly interested in their own benefit and less in the good of their organizations. There is also high tolerance for poor performance in the name of friendship, and the dynamics between individuals are dictated by workplace politics.

Goffee and Jones (1996, 1996) stated that in organizations with high solidarity, people think similarly and share tasks, and their mutual interests are directed toward the benefit of the organization and the achievement of its targets. The driving force behind decisions is logic. High solidarity gets the job done efficiently and effectively. Organizations with high solidarity place an emphasis on tackling the competition. The lack of friendships between employees is not apparent in day-to-day work life, as they work together to pursue the desirable output. Many employees enjoy working in such environments with clear roles, targets, and agreed-upon methods; however, in many cases, employees need additional attention and support from managers, which often does not exist in organizations with high solidarity.

On the other hand, in low solidarity environments, employees do not care about their co-workers and can experience high levels of internal conflict or exhibit insufficient interest in the organization. Such environments are also characterized by groups of employees who prioritize personal, non-organizational goals. Excessive emphasis on targets and achievements can lead to increased feelings of pressure or stress amongst employees, affecting their performance.

According to Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003), every employee belongs to a group that is characterized by sociability, solidarity, or both. The combination of the characteristics of sociability and solidarity generates the following four types of culture:

- (a)

networked culture (high sociability and low solidarity),

- (b)

mercenary culture (low sociability and high solidarity),

- (c)

fragmented culture (low sociability and low solidarity), and

- (d)

communal culture (high sociability and high solidarity).

Each type of culture has positive and negative aspects. The positive aspects are linked to employee behaviors that contribute to an organization's benefit, whilst the negative aspects are linked to behaviors that are detrimental to an organization.

Buenger (2000) mentions that Goffee and Jones's (1996, 2003) theory is based more on the practical implementation of concepts in large organizations and less on academic research. Ostrom and Hanson (2009) state that the suggested types of culture are broad and cannot capture the way daily work is carried out and that every organization and its employees are unique. Furthermore, whilst employees may have mutual concerns, benefits, and similar ideas on how to complete a project, conflicts may still arise between them (Jehn, 1997), making it difficult to categorize them into the same type of culture.

Today, conditions for organizations are continuously changing, rendering generalization risky. However, although theories that propose generic culture types are sometimes criticized for their simplicity, the theory proposed by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) provides a basis for the in-depth study of organizational culture in a straight-forward and practical manner and can assist leaders in better understanding their organizations and introducing innovations. The proposed types contain all the necessary organizational behavioral characteristics, such as behaviors toward risk taking, creativity and innovation as the last two are interrelated with the organizational culture, and need the appropriate value, norms and beliefs (Martins & Terblanche, 2003).

The various theories that propose generic types of culture share certain similarities. Thus, the mercenary culture and fragmented culture types proposed by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) are similar to Quinn and Rohrbaugh's (1981, 1983)adhocracy culture and Handy's (1981)person culture respectively. Another important issue related to organizational culture and the introduction of innovations is employee resistance. This can be reduced when employees fully understand the necessity for innovation (Washington & Hacker, 2005), through discussion and by being provided information on their potential benefits (Blair, 2000).

Finally, top management must establish an appropriate organizational culture that would support creativity and innovation (Martins & Martins, 2002) and cultivate conditions that support the adoption of innovations by employees whilst eliminating those that constitute impediments (McLean, 2005). This has become the main target of the present study.

2.3The Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM)The introduction of an innovation may fail because it is not used effectively by employees and consequently the expected benefits cannot be achieved (Klein & Knight, 2005). Thus, in order to be successful, management need to understand the factors that influence user acceptance, adoption and use of it (Venkatesh, Morris, & Ackerman, 2000). There are some models-theories which are particularly useful to managers providing the required information toward this direction. These models-theories have applied in a wide range of industries, although the majority of them have begun from the introduction of information technologies (IT). The most important of these are: the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) proposed by Davis (1989) and its evolution, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) proposed by Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, and Davis (2003); the Use-Diffusion Theory proposed by Shih and Venkatesh (2004); and the Innovation Diffusion Theory proposed by Rogers (1983). The CBAM is used widely for various kinds of innovations and was chosen for this study to show the factors that affected the success of PPI and specifically the use of an innovation.

The CBAM counts, describes, monitors, and explains the change process that results from the implementation of an innovation; it provides management with the information it needs to develop the appropriate strategies and make the necessary interventions in order to facilitate the change process (Chamblee & Slough, 2004; George et al., 2006; Hall, 2010; Hall & Hord, 2011; Hall et al., 2006). The research team that developed the CBAM believe that change starts with an individual employee and that management must focus on understanding what happens to those who implement an innovation, because its use may afford a differentiating advantage and lead to success (Hall et al., 2006; Sta. Maria, 2003). The basic assumptions of the CBAM are: (a) change is a process not an event; (b) the organization does not change until the individuals within it actually adopt and use an innovation; (c) change is a very personal experience for individuals; and, (d) in most cases, an innovation will be adapted to meet the needs and contingencies of the implementation context (Hall, 2013).

The CBAM consists of three tools/diagnostic dimensions: Stages of Concern (SoC), Levels of Use (LoU), and Innovation Configurations (IC). This study utilizes the first two, as these are described by George et al. (2006) and Hall et al. (2006) respectively, because they provide important insight into the dynamics that emerge during an innovation's introduction and which impact all employees. The SoC and LoU tools, satisfy the needs of this study; specifically, identifying the concerns about an innovation and its use by the employees of a particular public organization, providing a full picture of its implementation. The CBAM tools can be used independently or in combination, in pairs (Hall, 2013; Hall et al., 2006), and provide useful information on individual employees, groups of employees, departments, or the entire organization, regarding the introduction of an innovation (Hall, 2013). The third tool, IC, is used by leaders in order to develop the expected actions and behaviors for each person or role involved in the implementation of an innovation. This tool is not used here because it calls for interviews with and observation of employees, who, in this case, were scattered around the world, and this consist a limitation of the study. The SoC and LoU tools, which are used in the present study, are presented below.

2.3.1The stages of concern (SoC) toolThe behaviors of employees who are involved with the introduction of an innovation range from lack of interest and active resistance to full support of and participation in its implementation (Roach, Kratochwill, & Frank, 2009). Employee interest in a newly introduced innovation grows gradually, through the acquisition of new knowledge, experience, and skills (George et al., 2006).

George et al. (2006) and Hall (1976) proposed the following SoC experienced by employees during the introduction of an innovation: SoC 0: Lack of Concern, SoC 1: Information Seeking, SoC 2: Personal Issues, SoC 3: Management, SoC 4: Consequences, SoC 5: Collaboration, and SoC 6: Refocusing.

George et al. (2006) suggested that the simplest way to collect useful information is to determine and interpret the two highest SoC reached by employees and this is implemented in the present study. Data on the SoC were collected using the Stages of Concern Questionnaire (SoCQ) proposed by Hall, George, and Rutherford (1977).

After identifying individuals’ SoC, management must implement the appropriate interventions that will allow more employees to move to higher stages, which are in turn associated with improved results (George et al., 2006).

2.3.2The Levels of Use (LoU) toolThe LoU tool is a generic construct that can be applied to any case of introduction of an innovation (Hall et al., 2006). It consists of three parameters: (a) the seven categories, (b) the eight Levels of Use (LoU), and (c) the Decision Points. The combination of the seven categories and the eight LoU generates a set of specific statements that correspond to particular employee behaviors regarding an introduced innovation (Hall et al., 2006) and which were incorporated into this study's questionnaire. The Decision Points refer to the use of interviews, which were not conducted for this study, for the same reasons that the IC tool was not used. According to Hall et al. (2006), the seven categories are: (a) knowledge, (b) information, (c) discussion, (d) assessment, (e) planning, (f) description of personal statement, and (g) execution-use. Additionally, there are three profiles-levels of behaviors for non-users of an innovation—LoU 0: Non-use, LoU I: Orientation, LoU II: Preparation—and five profiles-levels for users—LoU III: Mechanical Use, LoU IV-A: Routine Use, LoU IV-B: Refinement, LoU V: Integration, and LoU VI: Renewal.

LoU 0 (non-use of the innovation) was not included in this study, because all employees-respondents used the innovation to a certain degree. However, statistical analysis—specifically, factor analysis of the statements regarding LoU—yielded a General LoU, which has been used in this study.

The LoU are determined using an interview that includes the three parameters (Hall, 2013; Hall et al., 2006). However, for the purposes of this study, the interview questions were carefully incorporated into the questionnaire, contrary to Hall's (2013) opinion. This method of assessing LoU gives a clear picture of the use of the innovation, and covers this study's requirements.

Most studies that used the SoC and LoU tools show: (a) the incremental evolution of the stages and levels that can be achieved by the introduction of the appropriate interventions (Dobbs, 2004; Olafson, Quinn, & Hall, 2005; Roach et al., 2009; Tunks & Kirk, 2009) and (b) the relationship between the two tools (Marsh, 1987; Olafson et al., 2005; Roach et al., 2009).

The CBAM has been the subject of criticism. Anderson (1997), Sherry and Gibson (2002), and Slough (1996) stressed that innovations today have become more complex: their introduction is not a static event; their adoption is often complicated; their use rarely progresses according to plan; and the process is influenced by numerous internal and external factors. Evans and Hopkins (1998), Hopkins (1990), and McKibbin and Joyce (1980) stressed that the CBAM does not factor in the organization's climate and leadership nor the psychological state of leaders who are involved in the implementation of an innovation. Another consideration is the CBAM's international implementation and the need for diligent translations of the questionnaire (Anderson, 1997). Bailey and Palsha (1992) speculate regarding the distinction of the stages themselves and suggest the integration of SoC 0 with SoC 1 and of SoC 4 with SoC 6.

Nonetheless, Anderson (1997) stressed that the CBAM is the most robust and empirically tested theoretical model of its kind. Initially applied mainly to educational innovations, it has been used in many more areas in recent years (Hall, 2013). Its many stages (of concern) and levels (of use) provide a clear picture of each individual employee and of the organization—its individual parts and as a whole—regarding concern about and use of an introduced innovation. Additionally, the emphasis given to individual employees involved in the innovation's introduction affords the CBAM an advantage over comparable models-theories. Another important advantage of the CBAM, and of the LoU in particular, is the detailed information it provides on the non-users of an innovation (the first three levels focus on non-users), as these employees require different kinds of interventions.

2.4The combination and the implementation of theoriesThe three theories mentioned above are evidently interrelated and can be combined in order to help leaders and researchers to better understand an introduced innovation and to ensure that it is widely used by employees. Thus, cultural traditions can be informal exogenous institutions (Rolfstam, 2012) and the various informal and formal endogenous and exogenous institutions influence the organizational culture. However, institutional theory helps “to explore how cultures within organizations are worked out in relation to cultures outside organizations, how organizational cultures are being transformed and translated through time, and what are the roles of actors in the work of organizational cultures” (Zilber, 2012, p. 88). In addition, institutional theory may explain individual employees’ concerns, contributing to increased use of an innovation.

The supplementation of the CBAM with the organizational culture types proposed by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) may shed light on the behavior of employees as regard the use of innovations and this is useful for managers. In addition, by examining the respondents’ replies to a series of other questions, this study found that participation in an innovation's introduction is a key factor that influences subsequent use of the innovation.

The CBAM and the generic culture types proposed by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) provided the institutional factors, and institutional theory provided the formal and informal endogenous institutions that shaped these institutional factors. These all had a significant impact on the use of innovation. The dynamics of this process are examined in this study.

As regard the PPI, the study's focus is on employees; specifically, it aims to fill the gap in the relevant literature by concentrating on: (a) individual employees and not groups of or the total of employees; (b) the quantification of the use of innovation by employees and not its adoption or diffusion, which lack the specificity; (c) the theories of the types of organizational culture proposed by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) and the CBAM model proposed by George et al. (2006) and Hall et al. (2006), which have been combined and adapted to the public procurement context; (d) the combination of the SoC and LoU, as suggested in the relevant literature (Hall, 2013); and (e) a public organization that operates in a hypercompetitive environment and has to compete with strong private organizations. In doing so, this study is making a contribution to the small empirical or field study of institutions (Azis & Wihardja, 2010).

The theories described above were applied to Olympic as a result of the organization's procurement of innovative technologies and of the requirement on its employees to use them. Thus, the LoU are the dependent variables of this study. The types of culture (negative and positive), employee concerns regarding the introduced innovation as assessed using the SoC, and the respondents’ participation in the introduction of an innovation constitute the study's institutional factors and its independent variables.

The study's research question is how the institutional factors of the specific types of culture (proposed by Goffee & Jones, 1996, 2003), the respondents’ concerns regarding the procured innovation expressed by SoC (proposed by George et al., 2006) and their participation in the introduction of an innovation affected the use of it by the employees, expressed by LoU (proposed by Hall et al., 2006).

3Research methodologyThis paper uses a single case study to achieve a comprehensible understanding of employee behavior regarding an introduced innovation. Whilst normally qualitative research is used to examine a case in depth, this study opted for quantitative research in order to quantify the use of the introduced innovation by employees. Thus, a questionnaire was used to collect the study's data. This questionnaire contained questions about the respondents’ characteristics such as their participation into introduction of innovation and included statements related to the examined theories. Specifically, in order to assess the SoC, it included statements from the SoCQ as well as the interview questions on the LoU, which were specially adapted for this questionnaire. The statements were carefully translated to Greek and adjusted to suit the study's needs.

For the questionnaire's construction, specific guidelines (regarding question length and wording and its overall appearance) were followed as recommended in the literature (Brace, 2008; Bradburn, Sudman, & Wansink, 2004; Oppenheim, 1992).

The questionnaire was then pilot tested (on eight employees-respondents) in order to test it in real conditions (Brace, 2008; Bradburn et al., 2004; Papanastasiou & Papanastasiou, 2005) and to increase the validity, reliability, and practicality of the research tool (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2000). The final questionnaire (which incorporated the suggested wording changes from the pilot testing) was electronically (by e-mail) sent to the study's respondents (112), and 102 were correctly completed. A sufficient response rate of 91% was achieved.

The collected data was statistically analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficients in order to uncover the relationships between the examined variables in pairs and multiple regression analysis in order to determine the relationships between the independent and dependent variables.

The majority (more than 92%) of the respondents belonged to the middle and lower hierarchical levels (Miles & Huberman, 1994) of the commercial and operations departments, because the new technologies were implemented primarily by those employees.

The researcher's own contribution was significant to the project, as he was: (a) the main contributor to the development of the Request for Proposal for the new technologies; (b) a member of the technical committee that assessed the offers from the various providers; (c) the Project Manager, responsible for implementing the new technologies and overseeing the progress of this process; and, (d) for a long time, professionally involved with the examined organization. The researcher's key role contributed substantially to the study's quality, facilitating access to all the necessary information and the affording the ability to discern respondent bias. The researcher was able to immediately recognize bias in certain respondents’ answers (e.g., regarding their education), and this was subsequently verified by cross-checking against the respondents’ personal data provided by the Human Resources Department—this question was not included in the statistics. Thus, the researcher successfully encountered the phenomenon described by Bradburn et al. (2004) as ‘social responsibility bias’.

4The case reportOlympic was the Greek state carrier for a long period (1957–2009) until its privatization in 2009 and subsequent purchase by its main competitor, Aegean Airlines. This study focuses on Olympic during a period when it was still a public organization.

According to Doganis (2001), Olympic was a bureaucratic organization that lacked a clear growth strategy and presented substantial financial losses. Regarding its organizational culture, Pangios (1997) and Potamianos (1999) noted the following characteristics:

- •

Employees were unwilling to take risks and seize opportunities.

- •

There were few individual employee initiatives and efforts to deal with difficult situations.

- •

Management failed to provide extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to employees (i.e., there was an existence of what Deci and Ryan (2000) refer to as amotivation).

- •

Recruitment of new employees was neither methodical nor meritocratic.

- •

The stories most recounted by employees had told of their colleagues’ personal efforts and successes, of Olympic's shortcomings, of management's bad decisions, of various security issues, and of the company's early days under Onnasis, its founder.

- •

Management failed to organize informational meetings for employees, whilst unions, in contrast, held such meetings frequently.

- •

The company lagged behind in the introduction of new technologies.

- •

There was insufficient training in processes, Information Systems (IS), and customer services.

- •

There were numerous employee groups and networks that prioritized personal gains over the good of the company.

- •

Olympic's buildings and workspaces were outdated, were not spatially concentrated, and lacked open-plan areas—all factors that contributed to the emergence of cliques and cluster groups.

- •

The Human Resources Department lacked direction and did not contribute to shaping a beneficial organizational culture.

- •

The lack of employee confidence in management, and the lack of both confidence and consensus amongst employees, created problems in the airline's daily operation.

- •

The permanent, lifetime employment status enjoyed by Olympic's employees contributed to the development of indifference toward the carrier's business and projects.

Olympic's IS were outdated, costly, sourced from multiple providers, and incapable of fulfilling the new requirements of the carrier's operations. Moreover, the IT Department suffered from a lack of investment, long-term planning, and adequately skilled new recruits and was struggling to support the carrier's other functions (Olympic Airways Services, 2008). Consequently, the carrier had no option but to turn to outsourcing in order to introduce new technologies.

Olympic was one of the few scheduled airlines to delay the introduction of e-ticketing dictated by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) (Reg. 722H), and further delay would have caused the airline severe problems. However, although Olympic had characteristics that did not facilitate the introduction of innovations, it successfully introduced modern and more cost efficient new technologies, complied with IATA's regulation regarding e-ticketing (722H), and offered a higher level of service to its customers. It also provided relevant training to almost 2500 employees. From the introduced new technologies only the e-ticketing was mandatory, the rest of technologies were introduced in order to improve the carrier's competitiveness. According to Malagas and Nikitakos (2008), the new technologies initially yielded positive results for Olympic.

Despite the fact that, during the entire period it was operational, Olympic had the manifold and complex societal objectives of a public organization (e.g., serve remote domestic destinations, ethnic traffic, voters) (Bugge et al., 2010) and had to compete with private carriers with very different objectives (e.g., maximize profits, increase market share), it successfully managed to procure and introduce an important innovation. This was achieved with the help of a project team made up employees with extensive experience and knowledge of the subject. As a result, the airline's management called for widespread use of the new technologies by its employees.

5Statistical analysis and resultsThe implementation of the Pearson's correlation coefficients and multiple regression analysis into the study's data is presented below.

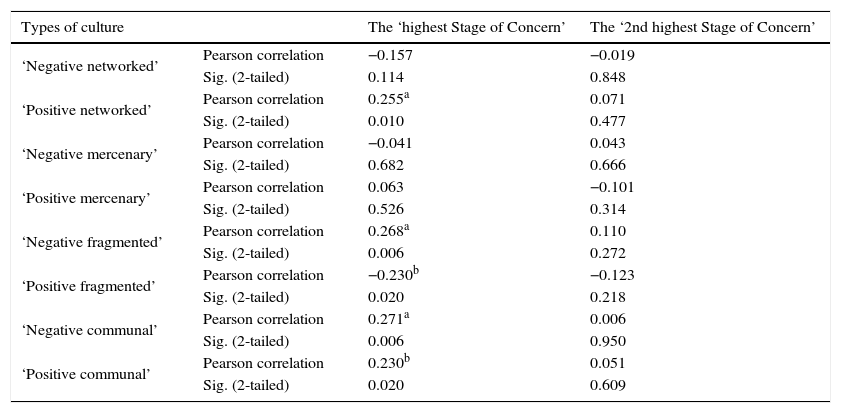

Tables 1–3 present the relationships between the study's variables in pairs, applying Pearson's correlation coefficients. In particular, Table 1 shows that there are relationships of the types of culture with the highest SoC and not with the 2nd highest SoC. The types of positive networked, the negative fragmented, negative communal and positive communal cultures are positively correlated with the highest SoC, while the positive fragmented type of culture is negatively correlated with the highest SoC, as the p-values (<0.01 and <0.05) shows.

Correlation coefficients between the types of culture and the ‘highest Stage of Concern’ and the ‘2nd highest Stage of Concern’.

| Types of culture | The ‘highest Stage of Concern’ | The ‘2nd highest Stage of Concern’ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Negative networked’ | Pearson correlation | −0.157 | −0.019 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.114 | 0.848 | |

| ‘Positive networked’ | Pearson correlation | 0.255a | 0.071 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.010 | 0.477 | |

| ‘Negative mercenary’ | Pearson correlation | −0.041 | 0.043 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.682 | 0.666 | |

| ‘Positive mercenary’ | Pearson correlation | 0.063 | −0.101 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.526 | 0.314 | |

| ‘Negative fragmented’ | Pearson correlation | 0.268a | 0.110 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.006 | 0.272 | |

| ‘Positive fragmented’ | Pearson correlation | −0.230b | −0.123 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.020 | 0.218 | |

| ‘Negative communal’ | Pearson correlation | 0.271a | 0.006 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.006 | 0.950 | |

| ‘Positive communal’ | Pearson correlation | 0.230b | 0.051 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.020 | 0.609 |

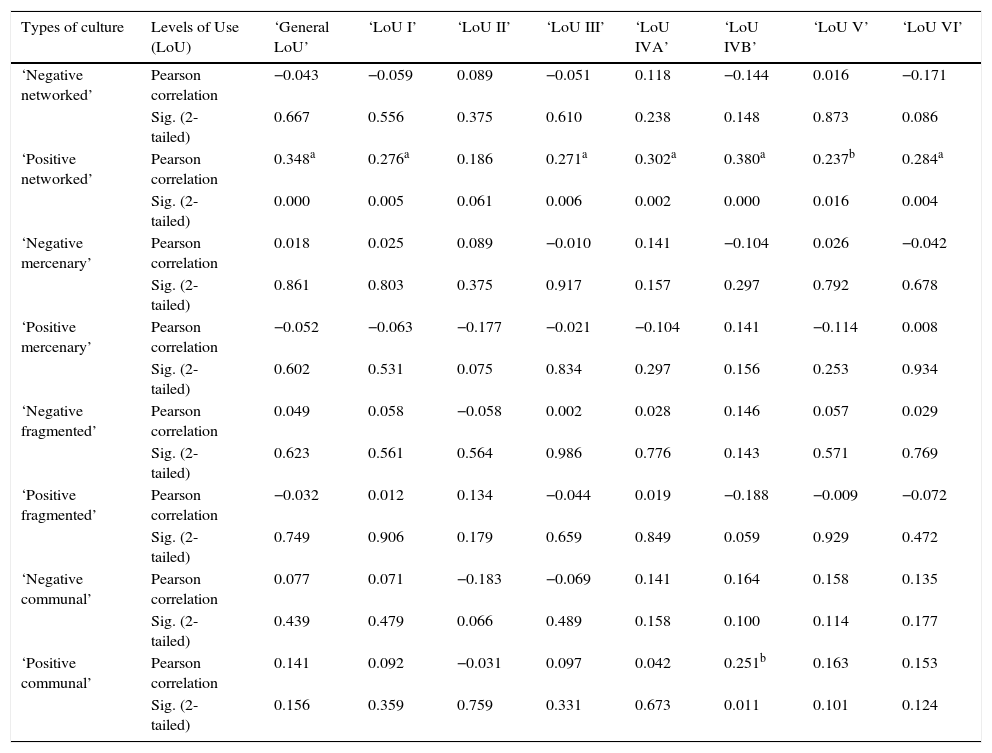

Correlation coefficients between the types of culture and the ‘Levels of Use’ (LoU).

| Types of culture | Levels of Use (LoU) | ‘General LoU’ | ‘LoU I’ | ‘LoU II’ | ‘LoU III’ | ‘LoU IVA’ | ‘LoU IVB’ | ‘LoU V’ | ‘LoU VI’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Negative networked’ | Pearson correlation | −0.043 | −0.059 | 0.089 | −0.051 | 0.118 | −0.144 | 0.016 | −0.171 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.667 | 0.556 | 0.375 | 0.610 | 0.238 | 0.148 | 0.873 | 0.086 | |

| ‘Positive networked’ | Pearson correlation | 0.348a | 0.276a | 0.186 | 0.271a | 0.302a | 0.380a | 0.237b | 0.284a |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.061 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.004 | |

| ‘Negative mercenary’ | Pearson correlation | 0.018 | 0.025 | 0.089 | −0.010 | 0.141 | −0.104 | 0.026 | −0.042 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.861 | 0.803 | 0.375 | 0.917 | 0.157 | 0.297 | 0.792 | 0.678 | |

| ‘Positive mercenary’ | Pearson correlation | −0.052 | −0.063 | −0.177 | −0.021 | −0.104 | 0.141 | −0.114 | 0.008 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.602 | 0.531 | 0.075 | 0.834 | 0.297 | 0.156 | 0.253 | 0.934 | |

| ‘Negative fragmented’ | Pearson correlation | 0.049 | 0.058 | −0.058 | 0.002 | 0.028 | 0.146 | 0.057 | 0.029 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.623 | 0.561 | 0.564 | 0.986 | 0.776 | 0.143 | 0.571 | 0.769 | |

| ‘Positive fragmented’ | Pearson correlation | −0.032 | 0.012 | 0.134 | −0.044 | 0.019 | −0.188 | −0.009 | −0.072 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.749 | 0.906 | 0.179 | 0.659 | 0.849 | 0.059 | 0.929 | 0.472 | |

| ‘Negative communal’ | Pearson correlation | 0.077 | 0.071 | −0.183 | −0.069 | 0.141 | 0.164 | 0.158 | 0.135 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.439 | 0.479 | 0.066 | 0.489 | 0.158 | 0.100 | 0.114 | 0.177 | |

| ‘Positive communal’ | Pearson correlation | 0.141 | 0.092 | −0.031 | 0.097 | 0.042 | 0.251b | 0.163 | 0.153 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.156 | 0.359 | 0.759 | 0.331 | 0.673 | 0.011 | 0.101 | 0.124 |

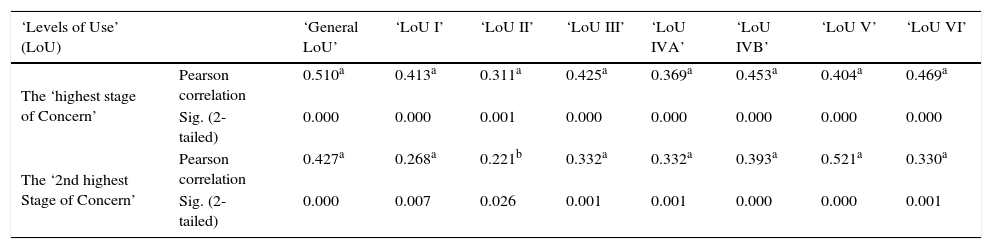

Correlation coefficients between the ‘highest Stage of Concern’, the ‘2nd highest Stage of Concern’ and ‘Levels of Use’ (LoU).

| ‘Levels of Use’ (LoU) | ‘General LoU’ | ‘LoU I’ | ‘LoU II’ | ‘LoU III’ | ‘LoU IVA’ | ‘LoU IVB’ | ‘LoU V’ | ‘LoU VI’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The ‘highest stage of Concern’ | Pearson correlation | 0.510a | 0.413a | 0.311a | 0.425a | 0.369a | 0.453a | 0.404a | 0.469a |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| The ‘2nd highest Stage of Concern’ | Pearson correlation | 0.427a | 0.268a | 0.221b | 0.332a | 0.332a | 0.393a | 0.521a | 0.330a |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.026 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

Table 2 shows the strong relationship of the positive networked type of culture on one side and the seven levels of use and the general level of use on the other side. Also, the positive communal type of culture is related with the 5th level of use. The other types of culture do not relate with the levels of use.

Table 3 shows the strong relationships of the stages of concern with the levels of use.

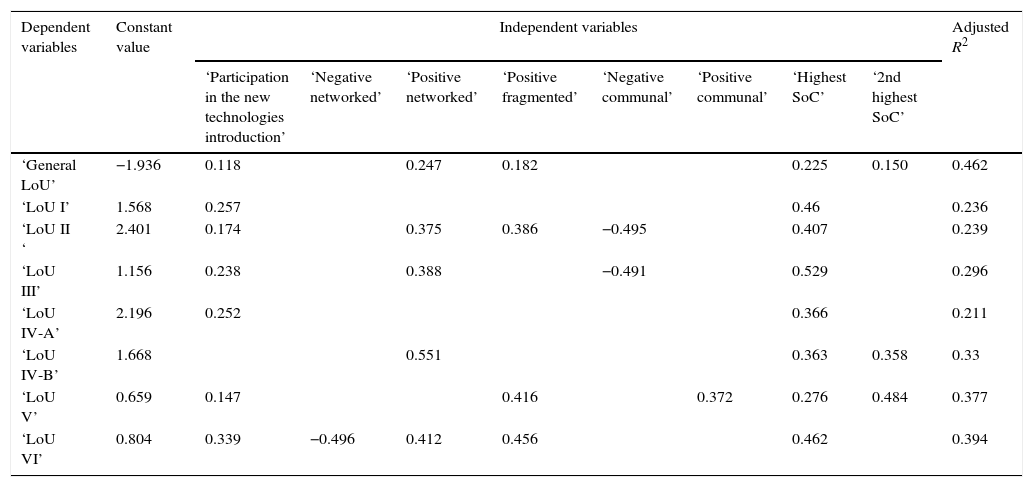

The following table shows the implementation of the MLR on the independent and dependent variables of the study, showing the relationships between them.

Table 4 shows the impact of each independent variable on the dependent, in measurement units of the last. The constant value was not taken into consideration; however, it represents what the value of the dependent variable would be if all independent variables were zero. The adjusted R2 is used as the assessment criterion of the adjusting ability of the model; its measurement is affected by the number of independent variables used in the model and the size of the sample (Theil, 1971). Thus, regarding the dependent variable General LoU, an increase by one unit of the independent variables ‘participation into the new technologies introduction’, ‘positive networked’ type of culture, ‘positive fragmented’ type of culture, ‘highest SoC’, and ‘2nd highest SoC’ has a positive impact on the dependent variable, increasing it by an average 0.118, 0.247, 0.182, 0.225, and 0.15 (in measurement units of the General LoU) respectively, provided that when one independent variable is changed, the rest of the variables remain unchanged. The adjusted R2=0.462 means that the independent variables explain 46.2% of the General LoU variance, and the remaining 53.8% is not related with them. The adjusted R2 is higher for the LoU IV-B, LoU V, and LoU VI (see Table 4), indicating that higher variance is explained by these particular independent variables, whilst lower variance is not related with them.

The implementation of the multiple linear regression (MLR) on the variables of the study.

| Dependent variables | Constant value | Independent variables | Adjusted R2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Participation in the new technologies introduction’ | ‘Negative networked’ | ‘Positive networked’ | ‘Positive fragmented’ | ‘Negative communal’ | ‘Positive communal’ | ‘Highest SoC’ | ‘2nd highest SoC’ | |||

| ‘General LoU’ | −1.936 | 0.118 | 0.247 | 0.182 | 0.225 | 0.150 | 0.462 | |||

| ‘LoU I’ | 1.568 | 0.257 | 0.46 | 0.236 | ||||||

| ‘LoU II ‘ | 2.401 | 0.174 | 0.375 | 0.386 | −0.495 | 0.407 | 0.239 | |||

| ‘LoU III’ | 1.156 | 0.238 | 0.388 | −0.491 | 0.529 | 0.296 | ||||

| ‘LoU IV-A’ | 2.196 | 0.252 | 0.366 | 0.211 | ||||||

| ‘LoU IV-B’ | 1.668 | 0.551 | 0.363 | 0.358 | 0.33 | |||||

| ‘LoU V’ | 0.659 | 0.147 | 0.416 | 0.372 | 0.276 | 0.484 | 0.377 | |||

| ‘LoU VI’ | 0.804 | 0.339 | −0.496 | 0.412 | 0.456 | 0.462 | 0.394 | |||

The purpose of this study is to determine how specific institutional factors—derived from the aforementioned theories—contribute (positively or negatively) to the success of the PPI and, specifically, to the use of an innovation by the employees of a public organization.

A high degree of the respondents’ participation throughout the various stages of the project to introduce innovation affected almost all the LoU, except LoU IV B (see Table 4). Specifically, many of the respondents participated in various committees for the selection of the new technologies provider, and then co-operated with the provider's staff to transfer Olympic's data (e.g., reservation data, IT systems) to the new system. The cascade method was applied to employee participation in the introduction of the new technologies (Alvesson & Sveningsson, 2008). After the initial phase, and as time passed, more and more employees and managers successfully engaged with the project. The initial successes reduced the resistance and anxieties of some employees, whilst others even took high-risk initiatives. Moreover, the project team managed to successfully involve a large number of employees in the introduction of the new technologies (i.e., the project), provided a high level of support through daily communication and training, and served as a model for behavioral change (Malagas, Nikitakos, & Ampartzaki, 2009). The participative leadership style adopted by the project's management resulted in greater commitment, improved performance, and stronger employee support for the project and its goals (Ismail, Ain Zainudd, & Ibrahim, 2010).

The study's respondents were members of the various groups of employees that influenced the operation of Olympic, worked closely alongside other friends-employees, actively participated in meetings, and engaged in casual work-related discussions with colleagues, often generating ideas that subsequently reached top management through the various informal networks (but which where, unfortunately, often delayed in their implementation) (Potamianos, 1999); these are all characteristics of a positive networked culture (Goffee & Jones, 1996, 2003). This type of culture positively affected: (a) the general use of the new technologies; (b) the respondents’ efforts to prepare for use of the new technologies (LoU II); (c) the respondents’ mechanical use of the new technologies (LoU III); (d) the respondents’ efforts to look for ways to continuously improve the new technologies (LoU IV-B); and (e) the respondents’ efforts to substantially modify or even replace the new technologies in order to increase their effectiveness (LoU VI) (see Table 4) (Hall et al., 2006).

The positive fragmented culture was characterized by respondents who exhibited individualistic behavior and took high risk initiatives (Goffee & Jones, 1996, 2003), yet still often had the support of the project team due to their significant specialist knowledge and experience. This pronounced individualism and the development of few initiatives by Olympic employees stemmed from a lack of shared objectives and efficient communication between functions and hierarchical levels (Doganis, 2001; Pangios, 1997; Potamianos, 1999), despite the fear of being penalized if said initiatives were unsuccessful (Pangios, 1997). Thus, Olympic had a small number of employees who did take initiatives (Don Quixote-style, according to Pangios, 1997), were open to change (Alvesson & Sveningsson, 2008), and were, in a sense, the airline's real employees (Potamianos, 1999). These individuals were driven by philotimo (literally, the love of honor)—a concept that lies at the heart of Greek culture and which refers to an altruistic sense of duty and decency driven by love and generosity (Potamianos, 1999)—as strong traditions and national culture affect employee behavior (Goffee & Jones, 2003; Rizescu, 2011). These respondents’ characteristics positively affected: (a) general use of the new technologies; (b) their efforts to prepare for use of the new technologies (LoU II); (c) their collaborative efforts to integrate/complement the new technologies with other initiatives (LoUV); and (d) their efforts to substantially modify or even replace the new technologies in order to increase their effectiveness (LoU VI) (see Table 4) (Hall et al., 2006).

The development of close relationships and friendships between respondents (high sociability) and a high interest in the project's and the company's success (high solidarity) are characteristics of a positive communal culture type (Goffee & Jones, 1996, 2003) and had been observed at Olympic during the period examined here, as well as during difficult periods in the organization's past (Potamianos, 1999). These characteristics positively influenced respondents’ efforts to integrate/complement the new technologies with other initiatives (LoUV) (see Table 4) (Hall et al., 2006). This communal culture type, usually seen in small organizations with good leadership (Goffee & Jones, 1996, 2003), occurred here primarily as a result of the project team's extraordinary ability.

Regarding the Stages of Concern, SoC 4 attained the highest value based on respondents’ answers to the SoCQ: respondents expressed increased interest in the ways in which new technologies affected customers and searched for ways to further improve these (George et al., 2006). These behaviors had positive effects on all the LoU (see Table 4), demonstrating a foreseen interrelationship between the CBAM's two tools.

The second highest value in the case examined here was SoC 5: respondents were keen to explore possibilities of working with colleagues toward maximizing the impact of new technologies (George et al., 2006). These behaviors were positively associated with: (a) the general use of the new technologies; (b) respondents’ efforts to look for ways to continuously improve the new technologies (LoU IV-B); and (c) respondents’ collaborative efforts to integrate/complement the new technologies with other initiatives (LoUV) (Hall et al., 2006) (see Table 4).

On the other hand, there are certain factors that are negatively associated with the use of new technologies. The negative networked culture at Olympic was characterized by the existence of numerous groups of employees whose primary interest was personal gain, by the emergence of cliques and informal politics, management's high tolerance for poor employee performance, no monitoring of said performance, and a general lack of motivation (Goffee and Jones, 1996, 2003; Pangios, 1997; Potamianos, 1999). These characteristics negatively impacted LoU VI (see Table 4), at which respondents were more skilled in the use of the new technologies (Hall et al., 2006).

The low sociability and low solidarity characteristics of the negative communal culture type (Goffee and Jones, 1996, 2003) prevalent at Olympic (Doganis, 2001; Pangios, 1997; Potamianos, 1999) seem to have negatively influenced: (a) the respondents’ efforts to prepare for use of the new technologies (LoU II), and (b) their mechanical use of the new technologies (LoU III) (Hall et al., 2006) (see Table 4).

This study is useful to leaders and researchers who want to learn about and gain valuable insight into the PPI process. Whilst the study's focus is on a public organization, its outcomes cannot only be applied to similar organizations but can also be used to generate useful ideas that can be applied to a wide range of situations where innovations are introduced. Olympic's characteristics—weak management, the introduction of new technologies under external pressure, excessive bureaucracy, a lack of focus on the competition, the existence of numerous groups of employees who were invested more in their personal gain (as individuals and as groups) and less in the good of the organization—corresponded to the low sociability and low solidarity attributes described by Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003) and created problems for the project. Nonetheless, the organization's management and the project team managed to successfully introduce the innovation, achieving high levels of use amongst employees and immediate positive results for the carrier (Malagas & Nikitakos, 2008). Consequently, this study offers important lessons. Thus, the increased participation of employees in the introduction of new technologies, the exploitation of those networks of employees (‘positive networked’ type of culture) and individuals (‘positive fragmented’ type of culture) that present positive behaviors toward organization and direct employees to express increased interest in the ways in which new technologies affected customers, are factors that positively affected the use of innovation and must be the focus of management in similar cases. On the other side, the low/negative sociability and low/negative solidarity (‘negative communal’ and ‘negative networked’ types of culture) must be avoided.

Leaders play a key role in the introduction of innovations (Goffee & Jones, 2003) and can significantly affect the behavior of employees, even getting them to act in specific ways (Mintzberg, 1983). This study demonstrated that institutional factors that contribute to increased use of new technologies presented above should be encouraged, whilst those that impede them should be dealt with by management, using all available tools. Management should aim to help employees achieve higher LoU (refinement, integration, renewal).

Thus, providing extrinsic or intrinsic motivation—or both—(Deci & Ryan, 2000), extensive training, progress updates (through speeches, newsletters, electronic communications, etc.), and support to employees, can, when combined with encouraging new behaviors, serve to enforce those factors that positively impact the use of innovations and counter those that impede their adoption.

Increased employee participation in all project stages was important and resulted in a high level of interest and commitment to the project and must, therefore, be encouraged by management.

The reinforcement of friendships through specially organized events, the creation of open areas in workplaces, and the recruitment of likeminded people with high sociability values are some of the measures that can be taken to increase the latter. Furthermore, the various informal employee networks that exist within organizations should be identified by management and turned to use toward the successful achievement of new targets.

Management should promote the organization's goals amongst employees and develop shared tasks that will benefit all involved parties and lead to improved performance (Niemann & Kotze, 2006). Thus, by setting a shared vision and mutual goals, management can ensure employee commitment and achieve high solidarity. However, management should also carefully facilitate the individual initiatives of those employees who have specialized knowledge and experience of the subject. These employees should be granted the necessary authority and should enjoy management's support, as these factors may well serve as incentive for them and contribute to a heightened sense of commitment to the organization.

Members of project teams who are responsible for the introduction of innovations must have the freedom to undertake high-risk activities, with the top management's full support, and to appoint employees with significant experience and knowledge of the subject, as this in the case of Olympic, significantly contributed to the successful introduction of the new technologies (Malagas, Kourousis, Baxter, Nikitakos, & Gritzalis, 2013). Thus, the introduction of new technologies and the problems that arise with this have a broad impact and require more than one person in order to be effectively managed. In such situations, individual autonomy is insufficient; instead, employees need to collaborate with colleagues, and efforts need to be coordinated.

Employees’ interest should be directed toward a continuous search for new ways to co-operate with their colleagues in order to maximize the benefits from the use of the new technologies for customers.

In public organizations, there are many employees with significant experience and considerable knowledge who should be efficiently made use of, as they can contribute to the development of high sociability and high solidarity and can take important autonomous initiatives.

By contrast, the low sociability and in particular the informal workplace politics and cliques that can be found in organizations with a long history, should be dealt with, as these behaviors are negatively associated with the highest LoU. Furthermore, low solidarity (also characteristic of the negative communal culture type; Goffee & Jones, 1996, 2003) should likewise be dealt with. Both negatively affect the preparation of employees for the introduction of new technologies and the mechanical use of these.

The various long-standing endogenous institutions that emerged within Olympic during its long history demonstrated a mainly political rationality and influenced the organization's performance. However, in this specific case, groups of employees that exhibited economic rationality outperformed those that exhibited political rationality, and had a positive impact on the use of innovation.

The above mentioned institutional factors were uncovered by means of an ideal combination of the CBAM and the theory of Goffee and Jones (1996, 2003). These factors were shaped by many informal and formal endogenous institutions, most of which were long-standing, that characterized Olympic and affected both its overall operation and the specific project. Management needs to identify informal institutions, as these can often be hidden, and, whilst some can become significant barriers to the successful introduction of innovations, others may facilitate the process; this task is easier for managers who have an in-depth knowledge of their organizations. Formal institutions, on the other hand, are easily identified. However, it is difficult to control and to change formal and informal institutions, as each kind requires a different approach.

Furthermore, management must also uncover the various rationalities that exist within their organizations and develop more economic rationalities, using all available tools at their disposal (motivation, training, awareness, etc.), as these can contribute to improved performance. Economic rationalities may also lead to higher solidarity and sociability, which are associated with increased use of innovations and, potentially, improved performance.

Also, management of public organizations must cooperate with their relevant governmental offices and press them to provide the necessary resources in order to procure innovative technologies and achieve significant performance improvements.

6.1Recommendations for future research and limitations of the studyThe role of the Greek state, specifically the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Transport, was significant in the case at hand, as both ministries acted quickly and fully supported Olympic. The successful introduction of innovation in the case of Olympic can serve as an example for other public organizations, and the experience gained by certain key employees in the involved ministries and authorities should also be utilized in other cases of PPI by the Greek state. Thus, factors that are related to levels above that of the organization (e.g., governmental agencies, multinational organizations, European directives for European organizations) need to be taken into account (Rolfstam, 2009) in future research, in order to better understand PPI determinants, as the introduction of innovation constitutes a multilevel issue (Rolfstam, 2012).

The implementation of IC would be useful, providing a better understanding of the process of the introduction of new technologies, and as this mentioned above consists a limitation of the paper. Moreover, the use of interviews for the collection of information regarding LoU consists another limitation.

The study examined a Greek company with particular characteristics, and its findings may have limited applicability to other environments such as European, American, or Asian organizations. Some useful conclusions were generated nonetheless.

The theories that were used in this study can be applied to additional organizations—with similar or different characteristics to Olympic—in order to obtain more comprehensive conclusions. Moreover, the same approach can be used to study the new privatized Olympic, in order to determine the effects of the carrier's privatization on the use of the new technologies and to comparatively examine the relevant institutional factors based on ownership status.

The theories can be applied to organizations where the new technologies are developed in-house and not outsourced and where their introduction is planned by management and not imposed by external factors as was the case with Olympic.

The examination of the relationship of the respondents’ demographics (such as the subject, place of work, etc.) with the independent variables of the study (types of culture, SoC) and the use of the new technologies would generate interesting results and this is another limitation of the study.

Finally, additional research should be carried out to determine the reasons why employees do not use newly introduced technologies, as this will help management make the necessary interventions in order to increase their use.

The proportions of variance accounted for in the dependent variables by the independent employed here are relatively low-medium, particularly for the lower LoU. This clearly indicates that, as expected, the LoU can never be fully explained by the independent variables alone. The use of a qualitative analysis—the approach most often used when studying PPI—can lead to a better understanding of the use of innovation, which in turn may uncover additional institutional factors; it is this that constitutes the main limitation of this study.