Long-term international assignments’ increase requires more attention being paid for the preparation of these foreign assignments, especially on the recruitment and selection process of expatriates. This article explores how the recruitment and selection process of expatriates is developed in Portuguese companies, examining the main criteria on recruitment and selection of expatriates’ decision to send international assignments. The paper is based on qualitative case studies of companies located in Portugal. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews of 42 expatriates and 18 organisational representatives as well from nine Portuguese companies. The findings show that the most important criteria are: (1) trust from managers, (2) years in service, (3) previous technical and language competences, (4) organisational knowledge and, (5) availability. Based on the findings, the article discusses in detail the main theoretical and managerial implications. Suggestions for further research are also presented.

The internationalisation of business, the globalisation of economy and the mobility of people and assets on a global scale have contributed to the increase in worker expatriation, bringing new challenges to international human resource management (IHRM). Expatriates were defined as those who are currently working or had previously worked in countries outside their country of origin (Collings, Scullion, & Morley, 2007), and included both self-initiated expatriates and company-assigned expatriates (Suutari & Brewster, 2000). In this article, we just study the company assigned expatriates. The company-assigned expatriates are employees send by a company to another company of the group, to live and work in another country for a period of 1 or more years, on an international assignment (Caligiuri, 2000; Bossard & Peterson, 2005; Martins, 2013) whether this be in traditional or long-term assignments (Collings et al., 2007). With the emergence of these groups of employees (Scullion & Brewster, 2001; Linehan & Scullion, 2002; Brookfield GRS, 2013), one of their main challenges is to help organisations attract and select their expatriates’ right skills for one international assignment. This supposition suggests that international organisations through their human resource management function have to be able to adjust (a) what this particular group of employees wants to, and (b) what the companies are willing to give (Aghazadeh, 1999).

In recent years, in spite of the continuing effects of the financial crisis that began in 2007, the growth of international mobility volumes as companies reported increases in the number of international assignments and higher expectations regarding future growth (Brookfield GRS, 2013). Obtaining economic growth becomes a must in the current period when the new economic normality triggers the emergence of crises in different fields (Ioneci, Antonescu, & Mîndreci, 2011).

Mainly long-term assignments continue to be used by companies for organising international work (Brookfield GRS, 2012). The question for multinational companies is how to select the right people. Much of the early work on long-term assignments was concerned with recruitment and/or selection of expatriates, such as the criteria used in such a decision (Suutari & Brewster, 2001).

Despite the importance of this theme in literature, empirical studies (e.g., Baruch, Steele, & Quantrill, 2002; Caligiuri & Colakoglu, 2007; Hippler, 2009; Paik, Segaud, & Malinowski, 2002; Welch, Steen, & Tahvanainen, 2009) focus mainly on companies based in the USA, the United Kingdom, Finland, Germany, and Australia, and studies of a similar nature in companies based in Portugal are unknown. This research intends, therefore, to continue the studies already conducted in other countries. It is the aim of the research to know how the international assignees’ recruitment and selection process is developed in Portuguese companies and to understand the role that the human resource management department has in this process. Despite the main focus of this research being on a specific geographic area (i.e., Portugal), it is expected that the data from this study will provide a basis for comparative analysis in an international context. In addition, the deficient candidates’ selection could be one cause responsible for assignment failure, but little attention has been paid to the methods of selection (Brookfield GRS, 2013).

This topic has a special relevance in the Portuguese context, since, to our knowledge (a) there are no empirical studies concerning this issue that involves expatriates from Portuguese companies; (b) the number of expatriates from Portuguese companies or subsidiaries into foreign MNCs’ head offices has grown; (c) little is known about expatriates recruitment and selection process used by Portuguese companies. The primary goal of this article is to increase the understanding of the development of the recruitment and selection process of expatriates in Portuguese companies. As a secondary specific goal, it identifies the main criteria used for the recruitment and selection of candidates for international assignments. We thus propose two research questions: (1) How the recruitment and selection process of candidates for international assignments in Portuguese companies is developed?; (2) Which are the main criteria used for recruitment and selection of expatriates for international assignments? Based on this, we set the research question concerning comparative analysis of recruitment and selection processes of nine companies selected for our study, namely is there some particular (or precise) understanding of recruitment and selection phenomenon in Portuguese companies. These goals help us to understand how Portuguese companies decide to attract and choose the expatriates to send to their foreign branches.

Using case studies and qualitative methods can provide an in-depth analysis of how managers and employees interpret what are the main criteria defined by companies on their recruitment and selection processes of international assignees.

This article focuses, in particular, on international recruitment and selection for expatriates’ long-term assignments. With this in mind, the article is structured as follows: after reviewing the literature on expatriates’ recruitment and selection, we present the method and then our findings. After exploring the main findings, we discuss the limitations of the study and paths for future research and we present the main conclusions.

2Recruitment and selection for international assignmentsExpatriates’ recruitment and selection is one main problem we can find in international human resource management literature (Suutari & Brewster, 2001). How to choose the right person is the major challenge for companies which develop international assignments.

Although Torrington (1994) suggests that there is no profile of the ideal expatriate that should be considered in the selection of expatriates, several authors (e.g., Avril & Magnini, 2007; Baruch et al., 2002; Caligiuri, 2000; Caligiuri, Tarique, & Jacobs, 2009; Hurn, 2007) suggest there are many important criteria that should be privileged during the expatriates’ recruitment and selection process. For many authors (e.g., Harvey & Novicevic, 2001; O'Sullivan, Appelbaum, & Abikhzer, 2002; Holopainen & Björkman, 2005; Avril & Magnini, 2007) it is mostly consensual that not only the previous international experience valorisation and the expatriate's ability to communicate, but also the recognition of personality issues and the way one thinks are also important requisites for successful expatriation recruitment.

Harvey and Novicevic (2001) concentrated their attention on some core personality characteristics for expatriate success (e.g., extroversion; agreeableness; conscientiousness; emotional stability; openness and intellect). In addition to these big five personality characteristics, others authors (e.g., Baruch et al., 2002; Caligiuri, 2000; Caligiuri et al., 2009; Hurn, 2007) admit other personal abilities as being also important such as adaptability to different norms and modes of behaviour, high tolerance for ambiguity, ability to work under stress; open-mindedness for developing and maintaining relationships with a variety of different groups of people, tolerance, patience, ability to work, independence, creativity, self-confidence and motivation.

At the same time, Harvey and Novicevic (2001) suggest that the recruitment and selection process should be focused on the competency-based expatriate selection perspective to combat the expatriate without knowledge of new market opportunities. These authors (Harvey & Novicevic, 2001) suggest that the company specific abilities are the ones that sustain the competitive advantage, such as the entrance abilities; meaning, these are the abilities that allow the company to effectively compete in global markets, given their products, services and people (e.g., human resources that generate value rare and inimitable value), its management ability, meaning the abilities that enable the implementation of new strategic visions for superior organisational performance through the development of a network between the entire company business units (e.g., business network management), along with abilities based on transformation, considered as the abilities that promote organisation knowledge through tacit knowledge transferred by expatriates, being very difficult to imitate by their competitors (e.g., management abilities to perform tasks that allow the gaining of a competitive position in the market or through the transfer of knowledge and other business units’ cultural attributes).

Another aspect to consider is the cultural aspect for which the individual will be sent to (Webb & Wright, 1996; Yavas & Bodur, 1999; O'Sullivan et al., 2002). One has to evaluate if the cultures between the origin countries are similar or different, since that differentiation may affect not only the mission performance but also the candidate's decision on accepting the international challenge (Webb & Wright, 1996; Harvey & Novicevic, 2001; Baruch et al., 2002). This assumption requires that the companies, in their recruitment and selection process, consider the candidate's international experience as a basic requisite, mainly in the host country, aiming to guarantee that the mission is successfully achieved. In parallel, it is known that many companies still ignore the importance of the partner and the family within the process of the candidates’ expatriation. Nevertheless, studies by Webb and Wright (1996), O'Sullivan et al. (2002) and Avril and Magnini (2007) claim the assumption that when partners are favourable to the international experience their adjustment becomes easier to perform as well as the expatriate's one.

Several researchers (Webb & Wright, 1996; Yavas & Bodur, 1999; Suutari & Brewster, 2001; O'Sullivan et al., 2002; Hurn, 2007) identify five categories of attributes related to the candidate's successful adjustment to expatriation, to be required in the formal Recruitment and Selection process: (1) labour issues, technical abilities and leadership abilities; (2) interpersonal abilities and previous performance evaluation; (3) motivational status and availability for a life abroad; (4) family situation and partner adaptation; (5) linguistic abilities, international experience, knowledge of the destination country and its culture. Nevertheless, the study by Suutari and Brewster (2001) developed in Finnish companies reveals that the majority of the expatriates were selected through informal methods. Another statement, by Harris and Brewster (1999) and Holopainen and Björkman (2005) reveal that companies continue to select their expatriates mainly by their technical abilities and previous performances.

The recent results of Brookfield GRS (2013) show that the top criteria for including employees in an international assignee candidate pool on companies are: the inclusion of high-potential employees in the candidate pool (70%), candidates who previously expressed a willingness to go on international assignments (57%), candidates with specific (rare) skills (30%), and candidates with previous international assignment experience and who had cultural ability or skills (17%). At the same time, competencies assessed during the candidate selection process included flexibility/adaptability (88%), technical skills (88%), leadership skills (81%), cross-cultural communication (63%) and family suitability (50%).

In summary, the literature suggests that expatriates’ recruitment and selection process is complex. We should, therefore, appreciate aspects such as cultural, economic and political differences between the host and home countries, individual and family characteristics and several competences of the expatriate (Harvey and Novicevic, 2001).

3MethodologyThis research uses a qualitative approach which provided the ability to elucidate rich, in-depth data on perception of individual and organisational issues. Qualitative research could make a substantial contribution to theory building in management (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2014). As part of the research design, Doz (2011) suggests that qualitative research methods offer the opportunity to help move the field forward and assist in providing their own theoretical grounding as well as to “open the black box” of organisational processes, the “how”, “who” and “why” of individual and collective organised action as it unfolds over time in context. Thus, the open nature of qualitative research provides a more likely opportunity to discover new phenomena worthy of research.

As pointed out by Doz (2011), in a new context, semi-structured interview data is a way to learn about that context in detail, identify and understand new phenomena as they arise and assess the extent to which they are worthy of academic research.

In order to improve credibility of qualitative research, we construct a preliminary model to ensure this credibility. A triangulated research approach was undertaken with several independent data sources and data collection methods used to ensure validity (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2007). Data analysis was based on the topics identified in the literature, in which the research questions were defined. Second, during the data collection phase, the transcripts were read by one researcher to gain an understanding of how each interviewee had their recruitment and selection process. During this process, both researchers undertook a systematic comparison between the themes highlighted by the interviewees and the initially coded themes. The researchers also compared the narratives of the interviewees to identify commonalities and differences in the unfolding of their recruitment and selection process.

3.1Cases and units of analysisWe conducted a multiple case study. Yin (2014) suggests that a multiple case study should present between 4 and 10 cases; we have a theoretical and intentional sample (Creswell, 2013) composed of nine companies. Two criteria were adopted to choose the cases. Firstly, the companies must be located in Portugal. Secondly, they should have expatriates.

3.1.1Data collection and analysisBetween October 2009 and January 2014, semi-structured interviews were conducted on international assignees (between four and seven per company). In total, sixty interviews were carried out (eighteen with organisational representatives and forty-two with international assignees). The purpose of these interviews was to ask the expatriates and organisational representatives from these nine companies to describe the recruitment and selection process. Particular attention was paid to data collection of the recruitment and selection process of international assignments. The expatriates described their individual experience and organisational representatives described the recruitment and selection process existing in the company that they represent as expatriates managers. All interviewees were native Portuguese and all interviews were conducted in Portuguese, by the same researcher. All interviews were conducted face-to-face (with exception for one interview, which was made by email because the expatriate was in Brazil at the moment when we did the data collection). The average duration of each interview was 70min. They were tape-recorded, the data were transcribed and categorised based on ‘commonalities and differences’ across emerging themes and then frequencies for each category were determined. They were assessed and interpreted using content analysis (Ghauri & Gronhaug, 2002).

To ensure anonymity, identification codes were assigned to each company: company A; company B; company C; company D; company E; company F; company G; company H; company I. Confidentiality was guaranteed for interviewees and the companies. In each company, international assignees were called interviewee (1, 2, 3 and 4) and organisational representatives were called ORGREP 1 or 2. An interview guide was used to ensure that similar data were collected from each expatriate.

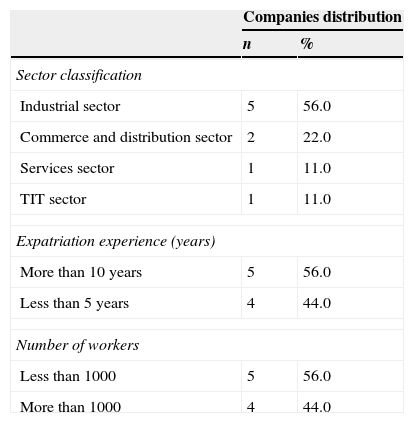

3.2Characterisation of the companiesAll companies were private and based in the North of Portugal: five comprised the industrial sector (companies A; B; C; D and E), two of them integrated the commerce and distribution sector (companies F and G), one belonged to the service sector (company H) and, finally, the last company (I) was in the telecommunications and information technologies business. All companies were based in Portugal. The majority (n=5) has less than one thousand workers. Five companies had had expatriation experience more than ten years before, and four of them had had this experience less than five years before. Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of companies included in the study.

Companies characteristics.

| Companies distribution | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Sector classification | ||

| Industrial sector | 5 | 56.0 |

| Commerce and distribution sector | 2 | 22.0 |

| Services sector | 1 | 11.0 |

| TIT sector | 1 | 11.0 |

| Expatriation experience (years) | ||

| More than 10 years | 5 | 56.0 |

| Less than 5 years | 4 | 44.0 |

| Number of workers | ||

| Less than 1000 | 5 | 56.0 |

| More than 1000 | 4 | 44.0 |

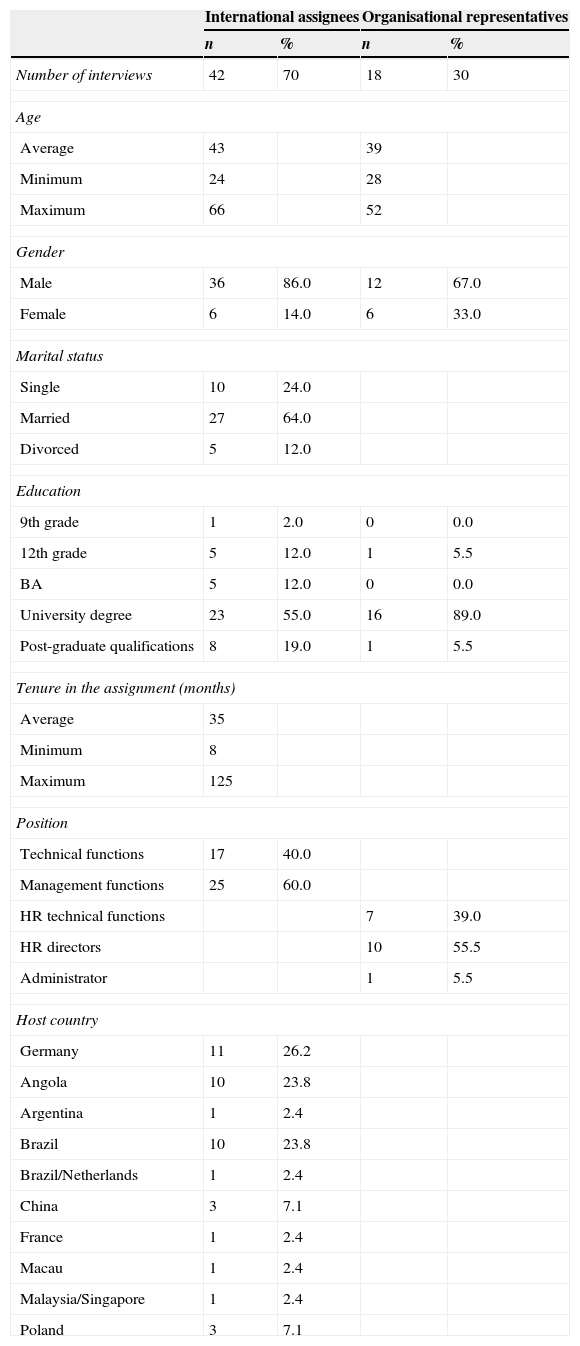

Eighteen organisational representatives (twelve males; aged 39 on average) have participated in this study. Seven performed technical functions related to the HR department (a lawyer, two operational managers and four technical coordinators) and eleven belonged to directors’ boards (ten human resources directors and an administrator). The majority possessed a university degree (n=16), one had a Masters’ degree and another had grade twelve.

Forty-two international assignees were interviewed (36 males; aged 43 in average). International assignments had several destination countries; Germany (n=11), Angola (n=10) and Brazil (n=10) were referred to as the most representative. The vast majority of the international assignees (n=23) possessed a university degree, eight of them had post-graduate qualifications (MBA and a Masters’ Degree), five had a BA, five had finished twelfth grade, and one had finished ninth grade. As for their marital status, 10 were single, 27 were married and 5 were divorced. When they were interviewed, 9 international assignees had performed technical functions and 33 performed direction functions (12 managers of intermediate level, 17 senior managers and 4 senior top managers). Seventeen performed technical functions and twenty-five performed management functions. Table 2 summarises the main demographic characteristics of participants in the study.

Participants demographic characteristics.

| International assignees | Organisational representatives | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Number of interviews | 42 | 70 | 18 | 30 |

| Age | ||||

| Average | 43 | 39 | ||

| Minimum | 24 | 28 | ||

| Maximum | 66 | 52 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 36 | 86.0 | 12 | 67.0 |

| Female | 6 | 14.0 | 6 | 33.0 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 10 | 24.0 | ||

| Married | 27 | 64.0 | ||

| Divorced | 5 | 12.0 | ||

| Education | ||||

| 9th grade | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 12th grade | 5 | 12.0 | 1 | 5.5 |

| BA | 5 | 12.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| University degree | 23 | 55.0 | 16 | 89.0 |

| Post-graduate qualifications | 8 | 19.0 | 1 | 5.5 |

| Tenure in the assignment (months) | ||||

| Average | 35 | |||

| Minimum | 8 | |||

| Maximum | 125 | |||

| Position | ||||

| Technical functions | 17 | 40.0 | ||

| Management functions | 25 | 60.0 | ||

| HR technical functions | 7 | 39.0 | ||

| HR directors | 10 | 55.5 | ||

| Administrator | 1 | 5.5 | ||

| Host country | ||||

| Germany | 11 | 26.2 | ||

| Angola | 10 | 23.8 | ||

| Argentina | 1 | 2.4 | ||

| Brazil | 10 | 23.8 | ||

| Brazil/Netherlands | 1 | 2.4 | ||

| China | 3 | 7.1 | ||

| France | 1 | 2.4 | ||

| Macau | 1 | 2.4 | ||

| Malaysia/Singapore | 1 | 2.4 | ||

| Poland | 3 | 7.1 | ||

We next present the empirical results regarding the recruitment and selection process of expatriates in Portuguese companies. We include representative quotes on the type of recruitment and selection, process duration and family issues.

4.1.1Type of recruitment and selectionThe companies in our study favour internal recruitment over the external one. All the interviewed expatriates had already worked in the home company before embracing an international mission.

The process of recruitment and selection is very informal and conducted directly between the administration and the candidate. The expatriates believe they were the only ones invited for the international mission they performed. I was invited by one of the company's administrator… the invitation was exclusively directed to me… (interviewee 2, company I). … the invitation was done in an informal and friendly conversation, as it is usual among the company administration… (interviewee 1, company F). There was no relationship. I didn’t apply, I was invited… (interviewee 2, company E)

The interviewed organisational representatives confirm these companies’ tendency to privilege the internal recruitment. The personalised invitation, based on a trustful relationship between the administration and the expatriated collaborator, is the most common procedure. These inviation procedure comes from the administration, in addition to the board of the human resources’ direction as well as by the market or the business direction, in which scope of the expatriation is intended. … it's identified, someone detaining the potential for the purpose, and once he is identified … the invitation is done… I don’t remember seeing an internal recruitment procedure, it was always by a directed invitation… (ORGREP 2, company G) … by invitation. In the functions of top responsibility framing, people were identified, very well identified, according to a perfectly defined profile, … (ORGREP 2, company C)

When the company does not have internal human resources to expatriate, but considers as fundamental the operations’ control through the headquarters located in Portugal, the alternative is to go for the external recruitment. This experience was confirmed by some organisational representatives: … when we don’t have available people inside we have to move forward to an external recruitment, where we analyse the speculative applications that we have, or we put an ad in the newspaper, or we hire a specialised company for the purpose. (ORGREP 1, company B) … but we can also have the case of not having people internally and, therefore, we go to the market trying to find out someone specifically for that mission, as it happened before. (ORGREP 1, company A)

Nevertheless, the external recruitment only occurs in case the invitations are denied, not being, therefore, applicable to all companies in our study. Companies G, H and I never went for the external recruitment for international missions abroad: … we seek internally, don’t find candidates, either because people didn’t want to go or because, you know, the market was not a nice one and, therefore, we need to go to the labour market. (ORGREP 2, company C) We do not go out for expatriating. Everyone that was expatriated was internal, and internals are not chosen by recruitment. People are identified as having the needed profile for the function and then they are naturally invited. (ORGREP 2, company G) … we never recruited anyone externally to fulfill an expatriation need. (ORGREP 1, company I)

The process of recruitment and selection in these companies has a variable duration, depending on the opportunities and needs of expatriation. On average, the process takes from 1 to 3 months in all companies. The process took about 2 months (interviewee 2, company B). Almost 3 months (interviewee 4, company H). … this process can take months. Well, I would say no more than three months, but it's a long process. (ORGREP 2, company G)

No company has the family inclusion issue formalised in its recruitment and selection process, although the expatriate's family situation is a determinant condition for some repatriates to accept the international mission:

… for me to accept the challenge I had, no doubt, a condition, I would go only if my wife went too… when putting this condition, not going if she didn’t go, they opened a possibility for her afterwards (interviewee 2, company I). …I was alone. I think this is one criterion to be selected. The company didn’t have a requirement to have our own family (interviewee 4, company A)

Nevertheless, companies show sensitiveness towards family issues, but consider it a personal question and not an organisational responsibility. The organisational representatives mention that the company is only responsible for the advising of the expatriate, in order to make him evaluate the family consensus before they communicate their final acceptance or refusal of the expatriation process. …since we do not force them to go here or there only because it is compulsory, our collaborators have to be responsible for their own decision… We take care of that… but there are no concrete measures in order to involve the family in the recruitment process. ORGREP 2, company D)

The main recruitment and selection criterion among all companies is based on trust from the administration on its expatriate candidates. Besides this criterion, one must add the adequate ability profile (company B; C; D; E; H; I), the organisational knowledge (company A; C; D; E; F; G), the years in service (company G; I) and availability (company A; C; D; E; F; G).

When the worker expatriation is for leadership functions, trust associated to an adequate ability profile is the privileged criterion. Individual availability, per se, has no relevance for this kind of mission. When, on the other hand, the function requires no high responsibilities, the candidate's availability prevails over the other selection criteria (common in Company A).

Here are some illustrations of the identified selection criteria:

4.2.1Trust from managersIt was trust, even because during many months, while the Brazilian H Company was not created… all the money that was sent, was coming directly to my bank account (interviewee 3, company H). The invitation was personalised… by the way they trust me, I suppose… (interviewee 2, company I). It has to be someone we trust. If the interviewee 4 didn’t accept to go, I doubt we had gone. He was a «sine qua non» question. (ORGREP 2, company H) … when there's an invitation it's always to a trustful person, … because it is very important. (ORGREP 2, company G)

… they wanted a team there… and I, at that time, showed interest… I was interested… (interviewee 4, company A). I always said I was available, so I had availability either for Portugal or abroad (interviewee 5, company G). … we obviously try to see if the people we identify… if they have or not the possibility to accept the international challenges. If they have, we make the invitation. (ORGREP 2, company A) I chose the interviewee 3 because she was not married… the interviewee 4 was also single. Therefore, they both had availability to go… (ORGREP 2, company H)

I believe that it was proposed to me because of my years in service in this company… (interviewee 2, company I). … after almost 25 years of service in this corporation, … so I can’t say no, it's a bit military (interviewee 4, company G). … because they are people that are with us for a long time now… (ORGREP 1, company I)

… I’ve worked all over the place: factories, countries, business units, everywhere (interviewee 2, company D). I have been working in this company for many years. From the beginning, I have changed my position every two years. When I was invited to go, I had deep organisational knowledge. For this I was selected (interviewee 2, company E). Those people on whom we … recognized that company organisational knowledge, the way of being, our company culture, those were the ones we sent. (ORGREP 1, company B)

… all that development performed by the company, the willingness to introduce the “Linen” programmes… I was precisely working on that, on creating the database and I totally understand the process [it was due to that technical knowledge that I was invited] (interviewee 3, company C). [the positions I had in the Brazilian company] were similar to the ones I performed here, with higher responsibilities, naturally, because we were starting from the basis, starting the company. It was in the Marketing area and here I was a marketing technician… (interviewee 2, company H). We had the case of one person that had done it but… when we talked to him we understood that he didn’t have the [technical] abilities and therefore we denied that possibility, … (ORGREP 1, company I) …they are people who are very specific in certain functions and that, for that reason, play that function in a very good way, being, therefore, the ones chosen to the most diverse projects… by their technical ability. (ORGREP 2, company C)

… even being in Poland, reports and meetings, etc. were conducted in English. I was fluent in English and, therefore, I was selected (interviewee 4, company C). …you have to know how to speak English, you have to know how to communicate in English, otherwise you will not be able to feel integrated in the German team… and that know-how I already had… I also had some German language knowledge… (interviewee 1, company E). … the foreign language issue is another factor that we also analyse. We make written tests and interview them in the foreign language to try to evaluate their competence there… (ORGREP 1, company I)

The results of this study indicate that in these companies there is a similar expatriates’ recruitment and selection process. Evidence reveals that this process is taken on in a very informal way and fully controlled by companies’ top managers.

Our study shows that the key criteria are: trust from managers, years of service, technical and languages’ competences, organisational knowledge and availability of candidates. Thus, the expatriates’ recruitment and selection process identified in these companies is incongruent with previous theoretical findings (e.g., Avril & Magnini, 2007; Bonache, Brewster, & Suutari, 2001; Noe, Hollenbeck, Gerhart, & Wright, 2012; Suutari & Brewster, 2001) which suggest that technical competences have been almost the sole variable used in deciding whom to send on international assignments, and that multiple skills are necessary for successful performance in these assignments (Caligiuri et al., 2009; Harvey & Novicevic, 2001). Other empirical studies (e.g., Born & Peltokorpi, 2010; Tungli & Peiperl, 2009; Peterson, Napier, & Shul-Shim, 2000) show that expatriates’ selection criteria vary significantly between American, European or Japanese companies. We take as and example the case of Germany, where the candidate's availability for expatriation is the major selection criterion. In Japan it is the experience in the company, while in the UK and the USA, the technical and adequate abilities are the most appreciated ones. The relational abilities, the personality and the ability to work in teams are also important criteria in all countries, although differently valued.

Our findings show that Portuguese companies tend to resemble companies in the United States of America (Noe et al., 2012) which have not invested much effort in attempting to make correct expatriate selections. For example, (1) there are no tests to determine the degree to which expatriate candidates possessed cross-cultural skills; (2) the choice of expatriates is not done from multiple candidates; (3) the companies in both countries emphasise only technical job-related experience and skills in making the selection decision.

Although several authors (e.g., Anderson, 2001; Caligiuri & Colakoglu, 2007; Harvey & Moeller, 2009) mention that the most strategic expatriation missions demand major concern with the selection processes (i.e., major rigour in the evaluation of interpersonal, technical and management competencies), the companies in our study privilege the candidates’ choice by their technical competencies and by the existent trustful relationship, revealing as insufficient the emphasis on the relational competencies and the candidate's family situation. In the studied companies, invitations are made preferably to internal collaborators, well know among the administration and on whom the company possesses good references about their professional performance. This method of selection differs among the literature (e.g., Avril & Magnini, 2007; Caligiuri, 2000; Martin & Anthony, 2006; O'Sullivan et al., 2002) and that suggests diversity among the selection criteria, namely the personality valorisation (e.g., self-esteem, integrity, safety, courage) and relevant relational competencies for the expatriation success (e.g., empathy, sociability, cordiality, consideration, extroversion, non-judging orientation). On the other hand, the control assumed in the process by the administration of our study's companies helps to understand the lower intervention role played by the HRM function in the candidates’ selection process. Nevertheless, this is a tendency corroborated by other similar studies with samples of European expatriates (Bonache et al., 2001; Harris & Brewster, 1999; Suutari & Brewster, 2001), whose selection results from a personalised invitation from the administration to a collaborator in whom it trusts, based on his performance and technical competence demonstrated along the professional history inside the original company. There are, therefore, reasons to believe that arbitrary in selection criteria may be explained by the lack of process formality among the companies of the present study. Our research additionally suggests that if family issues are included in expatriates’ recruitment and selection process it is easier for the expatriates to accept an international assignment. Nevertheless, in the companies of our study there were not family formal policies. Our results do not confirm the previous studies (e.g., Arthur & Bennet, 1995) which considered the family situation as the main important factor on selection for international candidates and future success in their international assignment. It is common to verify that these recruitment and selection programmes are, normally, directed to expatriates, excluding the relatives that go with them in their international mission (Linehan & Scullion, 2002). However, the tendency to include the family in the processes of recruitment and selection of the candidates has been growing since the 1980s. Since then, several authors (e.g., Harvey & Moeller, 2009; Haslberger & Brewster, 2008; Kraimer, Shaffer, & Bolino, 2009; Rushing & Kleiner, 2003) have assumed the family as a critical factor for the success of the expatriation/repatriation. This phenomenon also emerges in the obtained results, mainly in the companies that use expatriation for developing functions that are mainly strategic and not so much technical (companies C, E, F and G).

The results of our study are surprising on what concerns the possibility to reveal that most companies (i.e., companies A, B, F, H, I) seem to privilege candidates without family commitments, candidates that are starting their careers and, therefore, see the departure decision as a way to face job instability, or even candidates whose affective bonds to the company are higher to those with the family, sacrificing them for the company. Such results reveal that we are facing some specificity among the recruitment and selection processes in the companies located in the Portuguese context. It is possible that these particularities may be connected to the Portuguese companies’ HRM role. Although from the 90s, HRM in Portugal has been monitoring, real-time trends that are occurring in the organisational landscape (Neves & Gonçalves, 2009), Cunha et al. (2010) argue that there is still a long way to go, since even beginning to be seen as strategic, the influence of HR department in Portuguese firms is still limited. Especially, this role on expatriates’ management seems to be a little strategic. The little autonomy and little interventionist role of the HR department in expatriation management process may also contribute to the absence of formalisation of recruitment and selection process in companies of our study.

Research implications also emerge from this discussion. Firstly, it expands previous research on expatriates’ recruitment and selection process in the Portuguese context. Secondly, the empirical evidence results show that there are no mandatory criteria but there can be several criteria included in the expatriates’ selection, because all expatriates in our study accepted and fulfilled their international assignment. The main criteria for the candidates’ selection that we found were “the trust”, “years of service”, “technical and languages competences”, “organisational knowledge” and “availability” of candidates and not “family situation” or “big five” characteristics as recommended by the literature reviewed.

Our results suggest some managerial implications oriented towards the development of the recruitment and selection process so as to improve the expatriation management of these companies in particular. Specifically, we argue favourably towards the involvement of the HRM in this process in order to improve their capacity to plan and prepare in advance to the departure, a moment which takes on average from 1 to 3 months in all companies.

Finally, our study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings and should be considered when pursuing further research. Firstly, the approach adopted case study and in-depth interviews – that only allows abstract generalisation, i.e. contribution for theory. Future studies should take into consideration the theoretical contributions hereby presented and use quantitative approaches to validate and generalise findings. Moreover, future studies should include more Portuguese companies operating in several industries and in different internationalisation stages. On the other hand, the management strategy of the expatriates and the dimension of the company may help to explain some of the specificities in the recruitment and selection process found in the Portuguese companies compared to other countries. For example, the vaster experience in expatriation management from European countries to Asian and American countries can help to explain why different selection criteria were found in previous studies (e.g., Bonache et al., 2001; Harris & Brewster, 1999; Mayrhofer & Brewster, 1996; Tungli & Peiperl, 2009) but not replicated in the organisation of the companies involved in this research.

Some interviewees are not recent expatriates. This fact may have created difficulties in the recollection of the real criteria related with the recruitment and selection process at the time of the departure.

The relationship between the recruitment and selection process and the performance of expatriates during the international assignment has not been exploited, so future studies could analyse how the recruitment and selection process influences their performance and consequently his/her wish and the organisation's as well, to remain with or leave the company during and/or upon their international assignment.

To sum up, this study encourages more investigations to enhance and deepen knowledge on the subject and to help the expatriates’ recruitment and selection process of Portuguese companies.