Diagnosing individuals with co-occurring substance use and other mental disorders (SUDs and MDs) is challenging due to overlapping symptoms and masking effects. Semi-structured interviews, like the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM), are essential for diagnostic accuracy. This study aims to update and validate the Spanish PRISM-IV to DSM-5 criteria, providing evidence of reliability based on its ability to assess Dual Disorders (DDs).

Material and methodsThe PRISM-5 was translated and culturally adapted to Spanish to ensure equivalence with the original English version. The interview was computerized using BLAISE© software and pilot-tested. A cross-sectional study with patients recruited from specialized treatment centers in Spain and Argentina compared PRISM-5 diagnoses to those established through the Longitudinal, Expert, All Data (LEAD) method, providing evidence of diagnostic agreement through Cohen's kappa coefficient.

Results197 patients were recruited (69% male, mean age=35.6). PRISM-5 showed substantial evidence of diagnostic agreement for most SUDs (k=0.62–0.77), including alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, sedative, and amphetamine use disorders, with excellent agreement for past heroin use disorder (k=0.83). For MDs, substantial agreement was found for major depression, ADHD and psychotic, panic, and personality disorders (k=0.63–0.73), while moderate agreement was observed for substance-induced and persistent depression (k=0.59–0.60).

ConclusionsPRISM-5 provided strong evidence of diagnostic reliability in its Spanish version, with substantial agreement across most diagnoses. Compared to the PRISM-IV, it showed similar evidence of reliability, with some notable improvements in areas such as alcohol and cannabis use disorders. These findings underscore the instrument's robustness and value for diagnosing DDs.

Conceptual difficulties in establishing a common term for individuals with both a substance use disorder (SUD), and a co-occurring mental disorder (MD) persist, complicating effective treatment. To address this issue, recent efforts have focused on standardizing this concept, widely spreading the term “dual disorders” (DDs).1 The prevalence of DDs varies depending on factors such as the studied population, the substance consumed, and the specific MD under consideration.2 However, psychiatric comorbidities in individuals with SUDs are so common that they should be considered the norm, rather than an exception. This high comorbidity is reflected in prevalence data, showing that individuals with SUDs present MDs at a substantially higher rate (75%)3–5 than the general population (10.8%).6,7 Anxiety and mood disorders are the most frequently observed MDs in this group,8 with major depressive disorder leading the prevalence estimates and ranging from 12% to 80%.6,8–10

Several explanations account for the high prevalence of comorbidity between MDs and SUDs: (1) the presence of shared genetic and environmental risk factors; (2) the potential for sub-syndromic symptoms and MDs to drive to substance use; and (3) the fact that SUDs may trigger the onset of MDs.5,8,9 These bidirectional interactions between MDs and SUDs pose significant challenges in managing DDs, marked by characteristics that complicate both diagnosis and treatment. One major obstacle is determining the chronological sequence between the two disorders, as pinpointing the onset and progression of symptoms is often difficult.11 Furthermore, sub-syndromic symptoms may cause behavioral and emotional disturbances that contribute to both substance use and the emergence of additional psychopathological symptoms.12 Another barrier to accurate diagnosis is the potential masking of MD symptoms by the acute, chronic, or withdrawal effects of substance use.13,14 Additionally, in the absence of definitive biomarkers for MDs, standardized diagnostic criteria rely on a syndromic approach, adding further complexity to the process.14

Beyond diagnostic challenges, DDs are associated with a poorer prognosis, leading to greater deterioration in health and social functioning, while also incurring higher societal costs.15 Overall, patients with DDs face an elevated risk of various adverse outcomes, including a higher likelihood of suicide, more substance use relapses, increased treatment dropout rates, lower medication adherence, and a greater burden of medical comorbidities. They also face more emergency room admissions and hospitalizations, higher unemployment, increased involvement in violence and illegal behavior, and a heightened risk of social exclusion.14,16,17

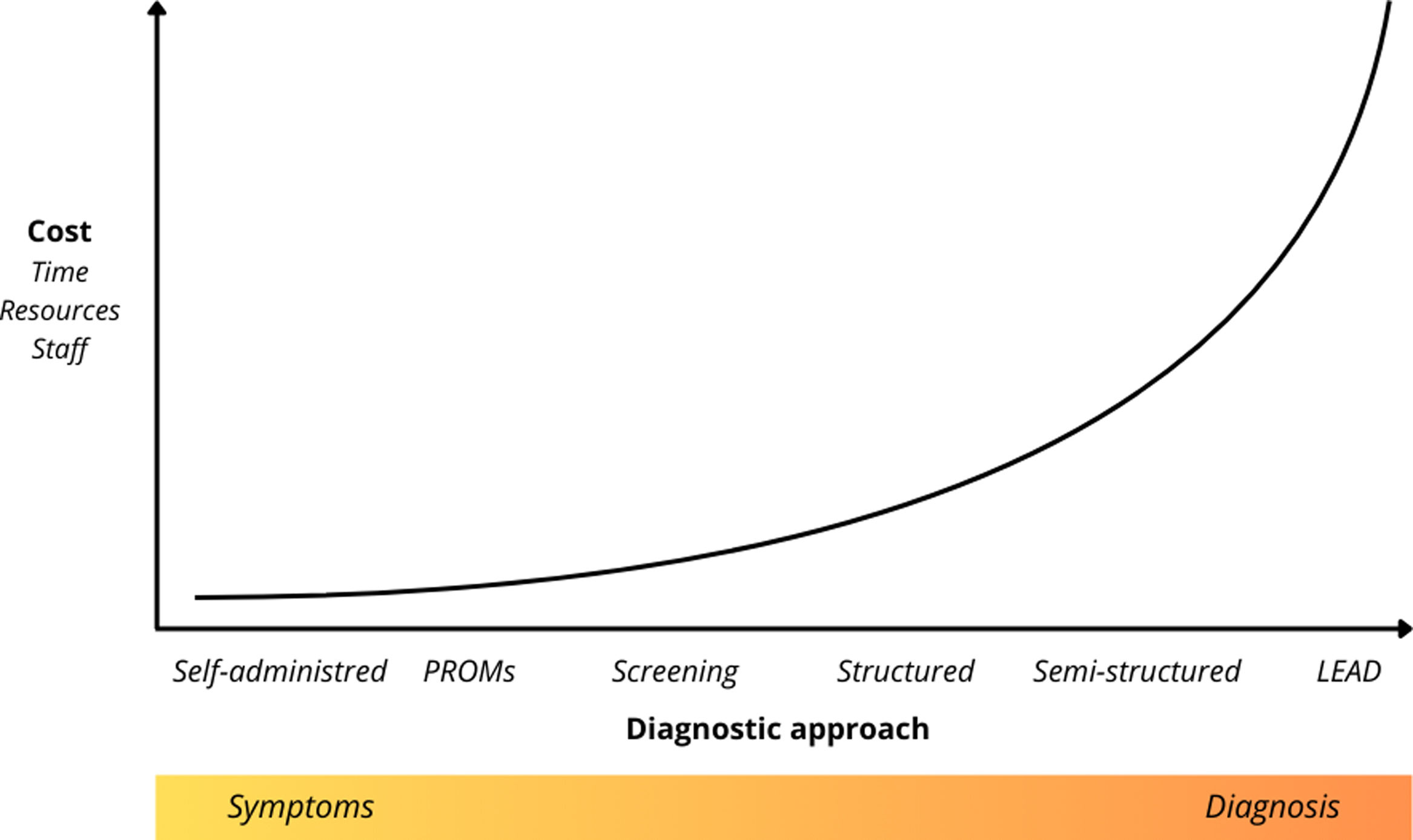

The accurate identification of these disorders is crucial to optimizing healthcare resources and tailoring treatment plans, making the use of specialized assessment tools essential for overcoming diagnostic barriers.13 In this context, the development of evaluation instruments has gained increasing importance, with a variety of tools now available, ranging from self-administered questionnaires to open interviews conducted by professionals. The choice of instrument will depend on the evaluation's purpose, as well as the time and resources available, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

This figure illustrates the relative implementation cost of different diagnostic approaches used in the assessment of dual disorders (DDs), plotted against the degree of clinical structure applied (from symptom-level assessment to fully structured diagnostic interviews). LEAD=Longitudinal, Expert, All Data35; PROMs=Patient-Reported Outcome Measures.

Symptom progression can be typically assessed using self-administered instruments and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs), with notable international initiatives like ICHOM promoting their widespread use.18 These and other screening tools help provide epidemiological estimates, identify potential disorders in settings with limited access to qualified professionals and resources,19 and determine whether a patient requires further attention for a particular issue. By screening for MDs in substance-using populations, early detection of comorbidities is facilitated, enabling more targeted treatments and improving overall prognosis.13

At the higher cost end of dual diagnostic tools are structured and semi-structured interviews, which are typically conducted by professionals and require extensive training. These instruments aim to systematize data collection, thereby providing stronger evidence for the validity and reliability of psychiatric diagnosis.8,9 Structured interviews follow a fully standardized approach, with questions asked verbatim, ensuring consistency and making them particularly useful for epidemiological studies. However, when addressing emotional experiences, the rigid questioning may create uncertainties, which require interviewers to be well-trained and have access to reference materials. In contrast, semi-structured interviews allow clinicians to clarify responses with unstructured follow-ups, improving clinical accuracy while introducing variability in data collection, making them more suitable for clinical settings.

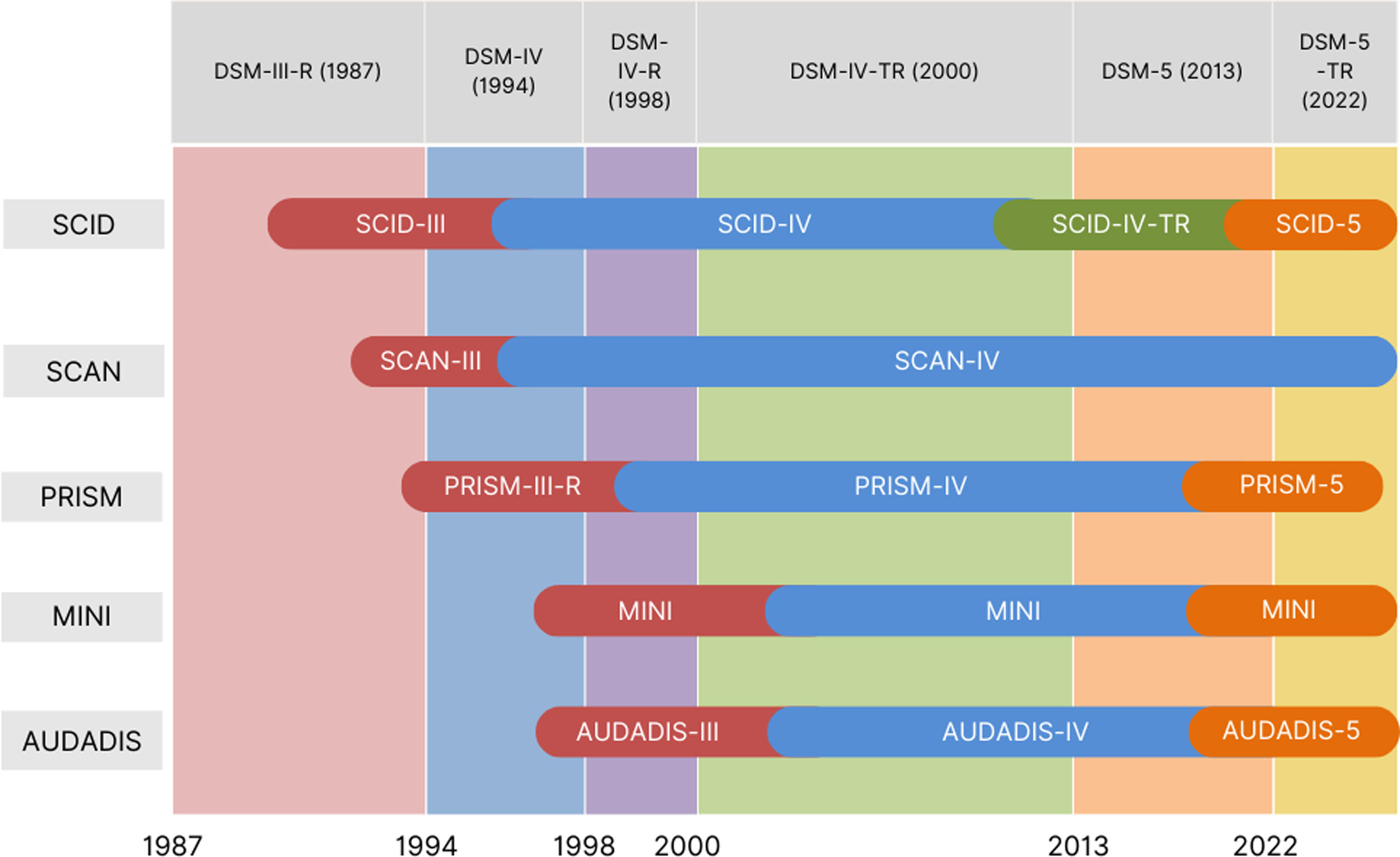

As diagnostic instruments evolve to keep pace with updates in classification systems and methodological improvements,14 new tools have been developed to address the specific challenges posed by DDs. Fig. 2 illustrates the progression of diagnostic manuals and the corresponding adaptations in interview versions, highlighting the challenges of adjusting to the constant evolution of criteria. This ongoing process has fueled the development of specific tools for assessing DDs, such as the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM), which was created in response to the changes introduced by the DSM-III-R (1987), which redefined SUD diagnosis.

This figure illustrates the historical development and adaptation of diagnostic interviews for mental and substance use disorders across successive versions of the DSM.20–22 This overview highlights the co-evolution of diagnostic criteria and assessment tools, reflecting the increasing emphasis on diagnostic precision and standardization in mental health research.

AUDADIS=Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule23; MINI=Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview24; SCAN=Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry25; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders.26 The PRISM interview is a semi-structured diagnostic tool designed for administration by a trained clinician. Created in 1990 (PRISM-III) the first version was based on DSM-III-R criteria,20 to address the lack of a diagnostic interview for researching the comorbidity of MDs in patients with SUDs. With the release of the DSM-IV,21 the interview was validated for both DSM-III and DSM-IV criteria, providing strong evidence of reliability.22 Due to its consistent performance and advantages over other semi-structured interviews, in 2001 it was further adapted to align to the DSM-IV (PRISM-IV).27 The latest version available, the PRISM-5, is fully computerized and adjusted to DSM-528 criteria, providing good evidence of diagnostic agreement for SUDs.29

One of its distinctive features from other diagnostic interviews is its initial focus on assessing SUDs before exploring other MDs. Substances assessed include alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, opioid analgesics, sedatives, stimulants, and tobacco. Additionally, it allows for differentiation between the expected effects of substance intoxication or withdrawal, substance-induced MDs, and primary MDs. This is achieved by collecting both current and past substance use history to establish a comprehensive timeline, identifying how SUDs may relate to other psychiatric conditions.30,31

Regarding its psychometric proprieties, previous studies have provided strong evidence of reliability and validity of different versions of the PRISM interview in populations with high rates of psychiatric and substance use comorbidity.29,32 For instance, in the validation study of the Spanish PRISM-IV version,33 the PRISM showed better agreement with the LEAD procedure than the SCID, seeming to indicate that the Spanish version of the PRISM is a better structured interview for diagnosing comorbid psychiatric disorders in a group of drug abusers. The main differences found were related to major depression, substance-induced psychosis, and borderline personality disorders. Regarding substance use disorder diagnoses, PRISM-IV also showed good to excellent concordance for most current dependence diagnoses including alcohol, anxiolytics, cocaine, and heroin. The only exception involved cannabis use, for which lower concordance was observed. However, this result should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of participants with a diagnosis of cannabis dependence in the sample. Similar difficulties in the evidence of reliability of DSM-IV cannabis dependence diagnoses have been reported with other instruments, including the AUDADIS-ADR and the SCAN.

More recently, PRISM-5 has demonstrated substantial to excellent evidence of test-retest agreement for DSM-5 substance use disorder diagnoses, with kappa values ranging from 0.63 to 0.94 for most substances, and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) between 0.74 and 0.99 for dimensional severity measures. Evidence of diagnostic agreement was moderate for hallucinogens, stimulants, and sedatives, and the craving criterion showed excellent agreement for heroin and moderate to substantial reliability for other substances. Notably, severity was the only factor found to influence diagnostic agreement, with lower agreement observed in milder cases.29

The Spanish version of the PRISM has demonstrated strong evidence of reliability30,32 and validity,33 having even been used as a reference standard for validating other diagnostic instruments.31 Building on its strengths, this study aims to update the latest version of the Spanish PRISM-IV to DSM-5 criteria, computerize the interview, and validate the resulting instrument by comparing its diagnoses with those provided by the patients’ referring psychiatrists, following the LEAD method (Longitudinal, Expert, All Data).34,35

MethodsProcedureThe Spanish version of the PRISM-5 was obtained through a rigorous and systematic process that incorporated the review and comparison of the Spanish PRISM-IV with the original English PRISM-5 version provided by its authors (Hasin et al.). Compared to the DSM-IV, the DSM-V introduced key changes to SUD criteria, including the addition of craving as a diagnostic criterion, assessed through questions about strong urges to use a substance. It also included cannabis withdrawal, and defined tobacco use disorder by combining nicotine dependence with abuse criteria. These updates were incorporated into the PRISM-5 assessment.29

Translations were meticulously conducted by a bilingual translator whose native language was Spanish, while the back-translation was performed by an experienced bilingual translator whose native language was English. The research team carefully reviewed all sections of the interview to identify and address discrepancies, make necessary corrections, and finalize the Spanish version. This process ensured that the translation maintained conceptual equivalence and cultural appropriateness across all components of the interview.

Once the text for the Spanish PRISM-5 was compiled—including introductions, questions, clarifications, response options, and all content related to its computerization, such as instructions, results, and error messages—the interview was implemented using the BLAISE© software. The new computerized Spanish version of the PRISM-5 underwent a comprehensive review, followed by pilot testing through eight interviews with volunteer patients. These tests were conducted to ensure proper functionality across all interview pathways and modules, as well as to verify the accuracy of data extraction.

At last, a cross-sectional study was conducted using a convenience sample. Diagnoses obtained through the PRISM-5 interview were compared to those established using the LEAD method, as determined by the participant's reference clinician at the time of recruitment. To ensure impartiality and prevent bias, neither the PRISM-5 interviewer nor the reference clinician had access to the diagnostic outcomes generated by the alternative method.

ParticipantsRecruitment for the study included a total of 197 patients and was conducted across various outpatient and inpatient services from participating centers. These included the Institute of Neuropsychiatry and Addictions (INAD) at Parc de Salut Mar, covering four addiction treatment centers Barceloneta, Fórum, Extracta-La Mina, and Santa Coloma, as well as the detoxification unit at Hospital del Mar and two dual pathology units at the Fòrum Center of Hospital del Mar and the Dr. Emili Mira i López Assistance Center (CAEMIL). Additionally, participants were also recruited from Vall Hebron addiction treatment centers, the Provincial Hospital Consortium of Castellón, and the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires in Argentina.

Inclusion criteria required participants to be aged 18 years or older and actively receive treatment for a current or past diagnosis of SUD at one of the aforementioned centers. Eligible participants were informed about the study by their clinician, and those who expressed interest were provided with a detailed description of the study, screened for eligibility, and asked to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included the presence of highly disturbing mental health conditions (e.g. psychotic symptoms), intellectual disabilities, significant language barriers and impairments in hearing, that could hinder understanding or affect participation in the study.

InstrumentsAll participants were assessed for SUDs and MDs using two diagnostic methods: the computerized Spanish version of the PRISM-5 and the LEAD method. The goal was to provide evidence of the reliability of the PRISM-5 interview by comparing its diagnoses with those obtained through the LEAD approach, widely regarded as the “Gold Standard” for clinical diagnosis.

The PRISM-5 is a semi-structured clinician-administered interview. It evaluates 22 disorders, including borderline and antisocial personality disorders, and must be administered by trained professionals to ensure standardized and reliable data collection. This interview was designed to assess psychiatric comorbidity in patients with SUDs, particularly distinguishing between substance-induced and primary disorders, from the expected effects of intoxication or withdrawal. This differentiation is achieved through a systematic assessment of both current and past substance use history, allowing the clinician to construct a comprehensive timeline and evaluate the temporal relationship between substance use patterns and the onset of psychiatric symptom.30,31

For example, to determine whether a depressive episode is substance-induced or independent, the interviewer asks: “Just before that time started when you were depressed, what was your drinking like? Had you recently cut back your drinking? Or started drinking more than you had been? Was there any change at all in your drinking habits?” And then, if the person interviewed answers affirmatively to any of these questions: “What was the change? When did that happen? Were you feeling depressed before you (increased/decreased) your drinking?”

Additionally, while the PRISM-5 interview allows for the assessment of an individual's prior mental health history, it does not systematically collect data on family psychiatric history. This limitation may reduce the contextual understanding of diagnostic outcomes, as family background can provide valuable information for interpreting mental health conditions.

Participants were also evaluated using the LEAD method, administered by their reference clinician at the time of recruitment. This method is based on three key elements: it is longitudinal, enabling the diagnosis of both current and past condition; it is conducted by expert clinicians; and it considers multiple data sources, including patient reports as well as information from family members and healthcare professionals.

Statistical analysisThe diagnoses obtained through the PRISM-5 interview and the LEAD method were categorized into two groups for analysis: current diagnoses (within the past 12 months) and past diagnoses (prior to the past 12 months).

For the comparison of both current and past diagnoses obtained through the PRISM-5 and the LEAD method, Cohen's kappa index (κ)36,37 was calculated to assess the chance-corrected agreement between both methods. The Kappa Index provides evidence supporting the reliability of a test by evaluating the degree of agreement between the results of two observations when applied to the same sample.36,38 Cohen's κ ranges from +1.00 to −1.00, with zero indicating chance-level agreement. The interpretation of the agreement level is as follows: <0.00, no agreement; 0.0–0.20, poor; 0.21–0.40: fair; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, substantial; 0.81–1.00, excellent.39–41 The greater the agreement between both methods, the higher evidence of the reliability of the instrument reliability of the instrument. Additionally, 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed to provide a measure of the precision of the kappa values. Diagnoses with very low prevalence (<2% in either diagnostic method) were not considered for analysis to ensure result stability. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were also calculated to assess the diagnostic performance.

Given the total sample size (N=197) and the uneven distribution of participants across age and gender, stratified analyses were not conducted. Grouping by demographic subcategories would have resulted in very small and heterogeneous subsamples, limiting the statistical power and undermining the interpretability of the results. This methodological decision is consistent with established practices in instrument validation studies, including the present PRISM-5 Spanish version, which required aggregating low-prevalence diagnoses into broader categories to ensure analytical robustness.

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 23.0.0.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 – Microsoft Office (MSO) – version 2201.

Ethical considerationsThe study was conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with applicable legal regulations regarding data confidentiality (Organic Law 15/1999 of December 13, Protection of Personal Data [LOPD]). The research was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research at Parc de Salut Mar (2014/5792/I; CEIC-PSMAR). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were given the opportunity to clarify any questions or address any concerns with a researcher involved in the study prior to participation.

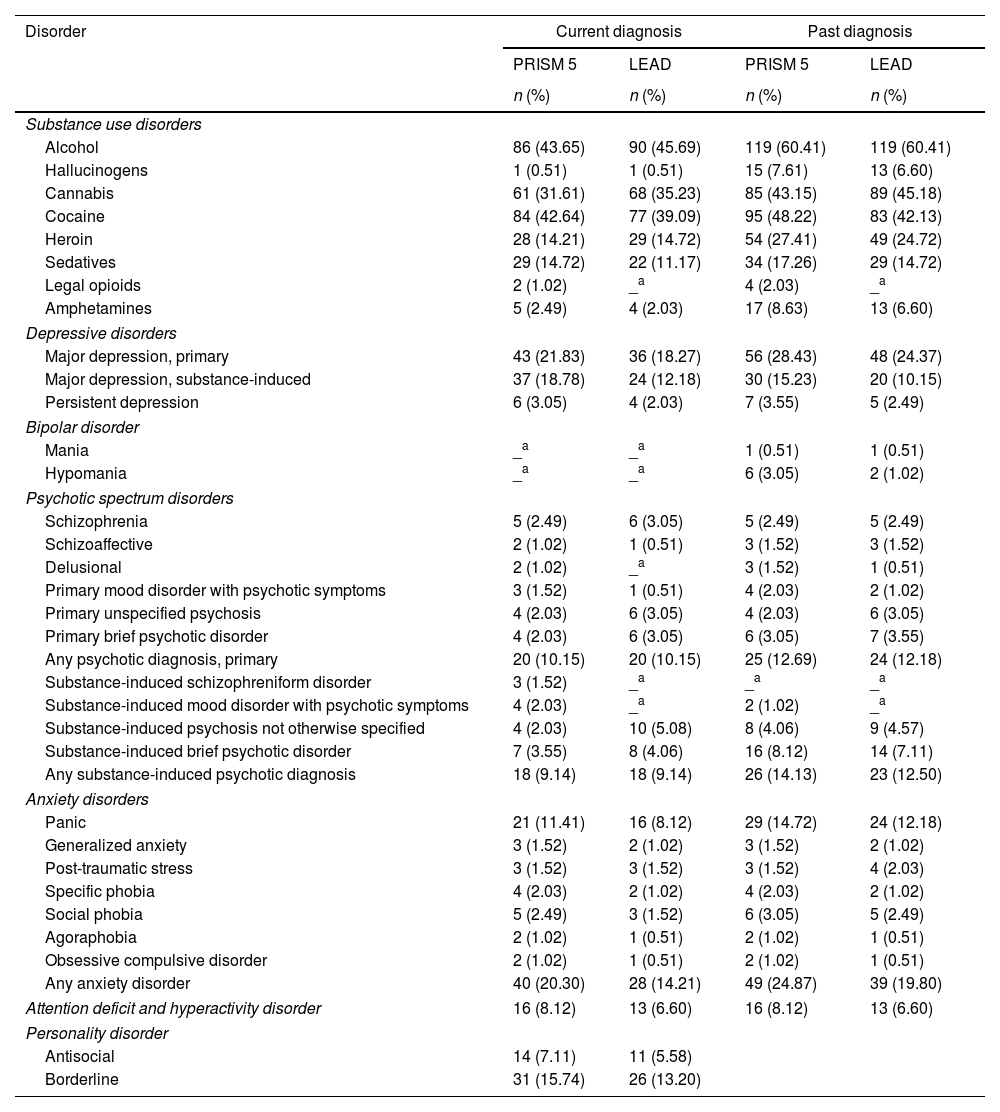

ResultsParticipantsA total of 197 patients were recruited for the study, of whom 69% were male and 31% female. The average age was 35.6 years (SD=±10), ranging from 18 to 64 years. Most participants were single (59.9%) and had completed secondary education or higher (61.9%). As seen in Table 1, prevalence of SUDs varied, with alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine being the most frequently reported substances, both current and past. In terms of MDs, the most reported were depressive disorders (both primary and substance-induced), anxiety disorders (particularly panic disorder), and borderline personality disorder.

Prevalence of diagnosed disorders (current and past) obtained through the Spanish version of the PRISM 5 and the LEAD method, N=197.

| Disorder | Current diagnosis | Past diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRISM 5 | LEAD | PRISM 5 | LEAD | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Substance use disorders | ||||

| Alcohol | 86 (43.65) | 90 (45.69) | 119 (60.41) | 119 (60.41) |

| Hallucinogens | 1 (0.51) | 1 (0.51) | 15 (7.61) | 13 (6.60) |

| Cannabis | 61 (31.61) | 68 (35.23) | 85 (43.15) | 89 (45.18) |

| Cocaine | 84 (42.64) | 77 (39.09) | 95 (48.22) | 83 (42.13) |

| Heroin | 28 (14.21) | 29 (14.72) | 54 (27.41) | 49 (24.72) |

| Sedatives | 29 (14.72) | 22 (11.17) | 34 (17.26) | 29 (14.72) |

| Legal opioids | 2 (1.02) | _a | 4 (2.03) | _a |

| Amphetamines | 5 (2.49) | 4 (2.03) | 17 (8.63) | 13 (6.60) |

| Depressive disorders | ||||

| Major depression, primary | 43 (21.83) | 36 (18.27) | 56 (28.43) | 48 (24.37) |

| Major depression, substance-induced | 37 (18.78) | 24 (12.18) | 30 (15.23) | 20 (10.15) |

| Persistent depression | 6 (3.05) | 4 (2.03) | 7 (3.55) | 5 (2.49) |

| Bipolar disorder | ||||

| Mania | _a | _a | 1 (0.51) | 1 (0.51) |

| Hypomania | _a | _a | 6 (3.05) | 2 (1.02) |

| Psychotic spectrum disorders | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 5 (2.49) | 6 (3.05) | 5 (2.49) | 5 (2.49) |

| Schizoaffective | 2 (1.02) | 1 (0.51) | 3 (1.52) | 3 (1.52) |

| Delusional | 2 (1.02) | _a | 3 (1.52) | 1 (0.51) |

| Primary mood disorder with psychotic symptoms | 3 (1.52) | 1 (0.51) | 4 (2.03) | 2 (1.02) |

| Primary unspecified psychosis | 4 (2.03) | 6 (3.05) | 4 (2.03) | 6 (3.05) |

| Primary brief psychotic disorder | 4 (2.03) | 6 (3.05) | 6 (3.05) | 7 (3.55) |

| Any psychotic diagnosis, primary | 20 (10.15) | 20 (10.15) | 25 (12.69) | 24 (12.18) |

| Substance-induced schizophreniform disorder | 3 (1.52) | _a | _a | _a |

| Substance-induced mood disorder with psychotic symptoms | 4 (2.03) | _a | 2 (1.02) | _a |

| Substance-induced psychosis not otherwise specified | 4 (2.03) | 10 (5.08) | 8 (4.06) | 9 (4.57) |

| Substance-induced brief psychotic disorder | 7 (3.55) | 8 (4.06) | 16 (8.12) | 14 (7.11) |

| Any substance-induced psychotic diagnosis | 18 (9.14) | 18 (9.14) | 26 (14.13) | 23 (12.50) |

| Anxiety disorders | ||||

| Panic | 21 (11.41) | 16 (8.12) | 29 (14.72) | 24 (12.18) |

| Generalized anxiety | 3 (1.52) | 2 (1.02) | 3 (1.52) | 2 (1.02) |

| Post-traumatic stress | 3 (1.52) | 3 (1.52) | 3 (1.52) | 4 (2.03) |

| Specific phobia | 4 (2.03) | 2 (1.02) | 4 (2.03) | 2 (1.02) |

| Social phobia | 5 (2.49) | 3 (1.52) | 6 (3.05) | 5 (2.49) |

| Agoraphobia | 2 (1.02) | 1 (0.51) | 2 (1.02) | 1 (0.51) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 2 (1.02) | 1 (0.51) | 2 (1.02) | 1 (0.51) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 40 (20.30) | 28 (14.21) | 49 (24.87) | 39 (19.80) |

| Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder | 16 (8.12) | 13 (6.60) | 16 (8.12) | 13 (6.60) |

| Personality disorder | ||||

| Antisocial | 14 (7.11) | 11 (5.58) | ||

| Borderline | 31 (15.74) | 26 (13.20) | ||

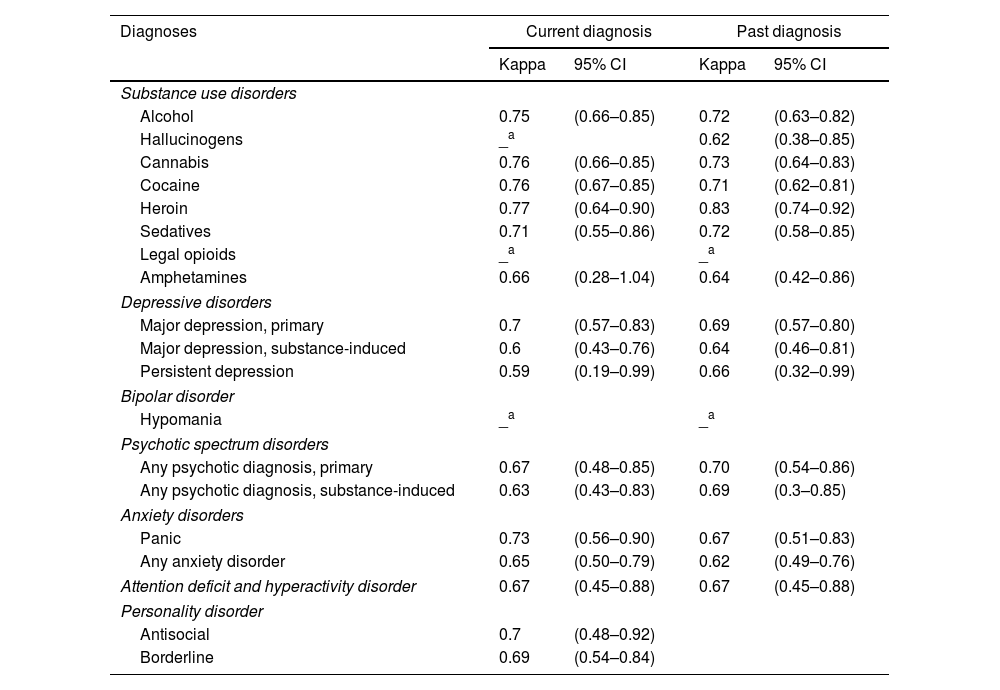

As shown in Table 1, the prevalence of SUDs, both current and past, was highly consistent when assessed using either the PRISM-5 or the LEAD method. Regarding current disorders, the reliability between the two instruments, was substantial for alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, sedative and amphetamine use disorders (k=0.66–0.77), as presented in Table 2. For past diagnoses, reliability evidence was substantial for alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, sedative, hallucinogen and amphetamine use disorders (k=0.62–0.73), and excellent for heroin use disorder (k=0.83). Agreement levels for current hallucinogen disorder and current and past opioid use disorders could not be tested due to their prevalence being too low in the sample.

Kappa value (k) and its “degree of agreement” between disorders (current and past) obtained through the Spanish version of the PRISM 5 and the LEAD method, N=197.

| Diagnoses | Current diagnosis | Past diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kappa | 95% CI | Kappa | 95% CI | |

| Substance use disorders | ||||

| Alcohol | 0.75 | (0.66–0.85) | 0.72 | (0.63–0.82) |

| Hallucinogens | _a | 0.62 | (0.38–0.85) | |

| Cannabis | 0.76 | (0.66–0.85) | 0.73 | (0.64–0.83) |

| Cocaine | 0.76 | (0.67–0.85) | 0.71 | (0.62–0.81) |

| Heroin | 0.77 | (0.64–0.90) | 0.83 | (0.74–0.92) |

| Sedatives | 0.71 | (0.55–0.86) | 0.72 | (0.58–0.85) |

| Legal opioids | _a | _a | ||

| Amphetamines | 0.66 | (0.28–1.04) | 0.64 | (0.42–0.86) |

| Depressive disorders | ||||

| Major depression, primary | 0.7 | (0.57–0.83) | 0.69 | (0.57–0.80) |

| Major depression, substance-induced | 0.6 | (0.43–0.76) | 0.64 | (0.46–0.81) |

| Persistent depression | 0.59 | (0.19–0.99) | 0.66 | (0.32–0.99) |

| Bipolar disorder | ||||

| Hypomania | _a | _a | ||

| Psychotic spectrum disorders | ||||

| Any psychotic diagnosis, primary | 0.67 | (0.48–0.85) | 0.70 | (0.54–0.86) |

| Any psychotic diagnosis, substance-induced | 0.63 | (0.43–0.83) | 0.69 | (0.3–0.85) |

| Anxiety disorders | ||||

| Panic | 0.73 | (0.56–0.90) | 0.67 | (0.51–0.83) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 0.65 | (0.50–0.79) | 0.62 | (0.49–0.76) |

| Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder | 0.67 | (0.45–0.88) | 0.67 | (0.45–0.88) |

| Personality disorder | ||||

| Antisocial | 0.7 | (0.48–0.92) | ||

| Borderline | 0.69 | (0.54–0.84) | ||

CI=confidence interval.

Interpretation of reliability coefficients: fair: 0.21–0.40; moderate: 0.41–0.60; substantial: 0.61–0.80; excellent: 0.81–1.00.

Regarding current and past diagnoses of MDs, the PRISM-5 generally reported higher prevalence rates for depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and personality disorders compared to the LEAD method (Table 1). Nonetheless, despite apparent differences, all Kappa indices (Table 2) demonstrated varying degrees of reliability between PRISM-5 and LEAD diagnoses, whether grouped or ungrouped. To increase the reliability of findings, diagnoses with very low prevalence (<2%) were grouped into broader categories, such as “Psychotic Spectrum Disorders” and “Anxiety Disorders,” which can be seen in Table 2.

For current disorders, substantial reliability was observed for major primary depression, primary psychotic disorders, substance-induced psychotic disorders, panic and anxiety disorders and ADHD, as well as for antisocial and borderline personality disorders (k=0.63–0.73). Additionally, moderate reliability was noted for substance-induced major depression and persistent depression (k=0.59–0.60).

Regarding past MDs, substantial agreement was also observed for most diagnoses, including all depressive disorders, primary psychotic disorders, substance-induced psychotic disorders, panic and anxiety disorders and ADHD (k=0.62–0.70). For lifetime hypomania diagnosis, Kappa indexes could not be obtained due to low rates.

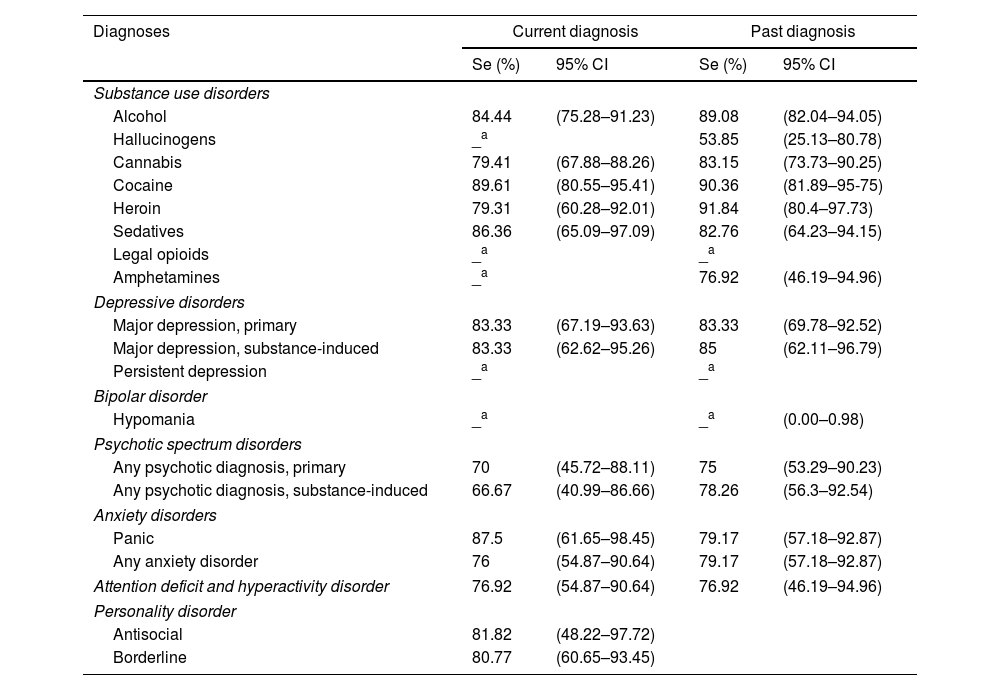

Validity evidence indicators of PRISM-5In SUDs, the PRISM-5 showed sensitivity values ranging from 79.31% to 89.61% for current diagnoses, with the lowest sensitivity found in Heroin Use Disorder and the highest in Cocaine Use Disorder (Table 3). For past SUDs, sensitivity ranged from 53.85% to 91.84%, corresponding to Hallucinogen Use Disorder and Heroin Use Disorder, respectively. In other current MDs, sensitivity ranged from 66.67% in the category for Any Substance-Induced Psychotic Disorder to 87.5% in Panic Disorder. On the other hand, for past MDs, sensitivity went from 75% to 85% in Any Substance-Induced Psychotic Disorder and Substance-Induced Major Depressive Disorder, respectively.

Sensibility (Se) and its respective confidence intervals for each disorder (current and past) obtained through the Spanish version of the PRISM 5, N=197.

| Diagnoses | Current diagnosis | Past diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Se (%) | 95% CI | Se (%) | 95% CI | |

| Substance use disorders | ||||

| Alcohol | 84.44 | (75.28–91.23) | 89.08 | (82.04–94.05) |

| Hallucinogens | _a | 53.85 | (25.13–80.78) | |

| Cannabis | 79.41 | (67.88–88.26) | 83.15 | (73.73–90.25) |

| Cocaine | 89.61 | (80.55–95.41) | 90.36 | (81.89–95-75) |

| Heroin | 79.31 | (60.28–92.01) | 91.84 | (80.4–97.73) |

| Sedatives | 86.36 | (65.09–97.09) | 82.76 | (64.23–94.15) |

| Legal opioids | _a | _a | ||

| Amphetamines | _a | 76.92 | (46.19–94.96) | |

| Depressive disorders | ||||

| Major depression, primary | 83.33 | (67.19–93.63) | 83.33 | (69.78–92.52) |

| Major depression, substance-induced | 83.33 | (62.62–95.26) | 85 | (62.11–96.79) |

| Persistent depression | _a | _a | ||

| Bipolar disorder | ||||

| Hypomania | _a | _a | (0.00–0.98) | |

| Psychotic spectrum disorders | ||||

| Any psychotic diagnosis, primary | 70 | (45.72–88.11) | 75 | (53.29–90.23) |

| Any psychotic diagnosis, substance-induced | 66.67 | (40.99–86.66) | 78.26 | (56.3–92.54) |

| Anxiety disorders | ||||

| Panic | 87.5 | (61.65–98.45) | 79.17 | (57.18–92.87) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 76 | (54.87–90.64) | 79.17 | (57.18–92.87) |

| Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder | 76.92 | (54.87–90.64) | 76.92 | (46.19–94.96) |

| Personality disorder | ||||

| Antisocial | 81.82 | (48.22–97.72) | ||

| Borderline | 80.77 | (60.65–93.45) | ||

CI=confidence interval.

Interpretation of sensitivity: poor: <0.50; moderate: 0.50–0.69; good: 0.70–0.89; excellent: ≥0.90.

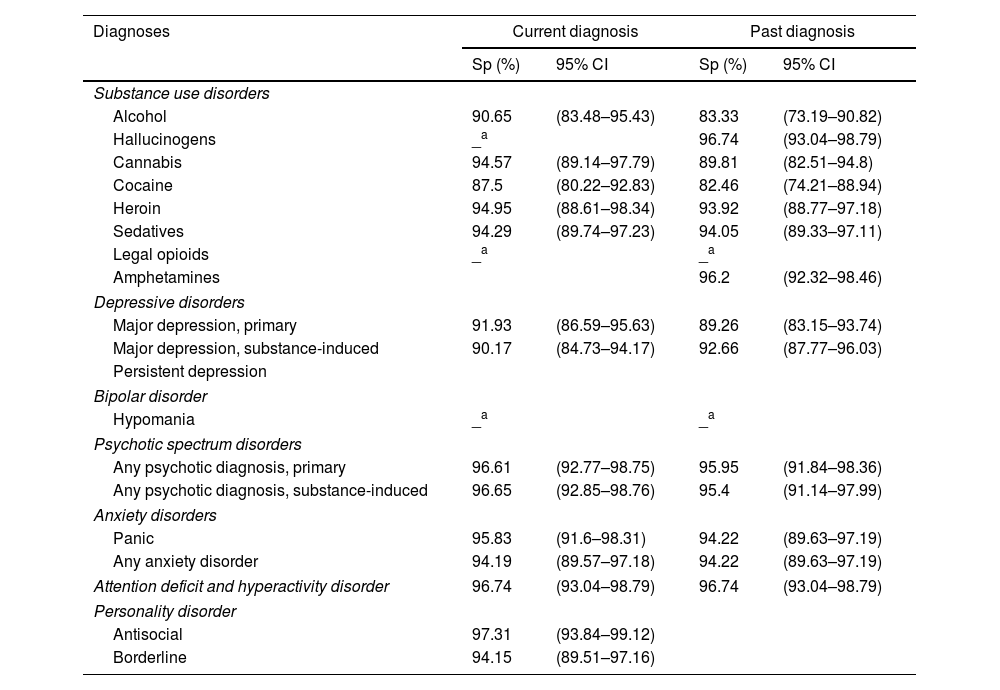

For current SUDs, specificity values ranged from 87.5% to 94.95%, with the lowest specificity in Cocaine Use Disorder and the highest in Heroin Use Disorder. For past SUDs, specificity ranged from 82.46% to 96.74% in Cocaine Use Disorder and Hallucinogen Use Disorder, respectively. In current MDs, specificity was lowest at 90.17% for Substance-Induced Major Depressive Disorder and peaked at 97.31% for Antisocial Personality Disorder. Among past MDs, specificity ranged from 89.26% for Primary Major Depressive Disorder to 96.74% for ADHD (Table 4).

Specificity (Sp) and its respective Confidence Intervals for each disorder (current and past) obtained through the Spanish version of the PRISM 5, N=197.

| Diagnoses | Current diagnosis | Past diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp (%) | 95% CI | Sp (%) | 95% CI | |

| Substance use disorders | ||||

| Alcohol | 90.65 | (83.48–95.43) | 83.33 | (73.19–90.82) |

| Hallucinogens | _a | 96.74 | (93.04–98.79) | |

| Cannabis | 94.57 | (89.14–97.79) | 89.81 | (82.51–94.8) |

| Cocaine | 87.5 | (80.22–92.83) | 82.46 | (74.21–88.94) |

| Heroin | 94.95 | (88.61–98.34) | 93.92 | (88.77–97.18) |

| Sedatives | 94.29 | (89.74–97.23) | 94.05 | (89.33–97.11) |

| Legal opioids | _a | _a | ||

| Amphetamines | 96.2 | (92.32–98.46) | ||

| Depressive disorders | ||||

| Major depression, primary | 91.93 | (86.59–95.63) | 89.26 | (83.15–93.74) |

| Major depression, substance-induced | 90.17 | (84.73–94.17) | 92.66 | (87.77–96.03) |

| Persistent depression | ||||

| Bipolar disorder | ||||

| Hypomania | _a | _a | ||

| Psychotic spectrum disorders | ||||

| Any psychotic diagnosis, primary | 96.61 | (92.77–98.75) | 95.95 | (91.84–98.36) |

| Any psychotic diagnosis, substance-induced | 96.65 | (92.85–98.76) | 95.4 | (91.14–97.99) |

| Anxiety disorders | ||||

| Panic | 95.83 | (91.6–98.31) | 94.22 | (89.63–97.19) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 94.19 | (89.57–97.18) | 94.22 | (89.63–97.19) |

| Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder | 96.74 | (93.04–98.79) | 96.74 | (93.04–98.79) |

| Personality disorder | ||||

| Antisocial | 97.31 | (93.84–99.12) | ||

| Borderline | 94.15 | (89.51–97.16) | ||

CI=confidence interval.

Interpretation of specificity: poor: <0.50; Moderate: 0.50–0.69; Good: 0.70–0.89; Excellent: ≥0.90.

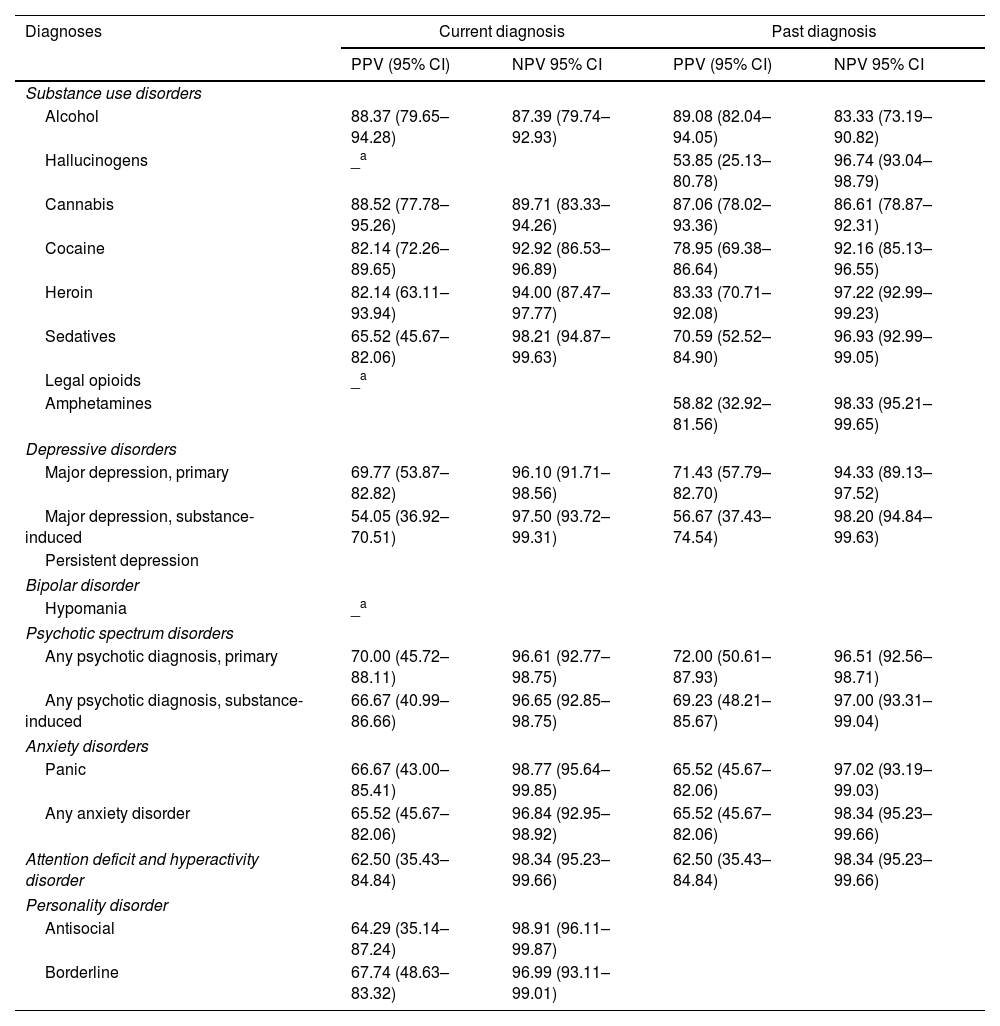

For current SUDs, the PPV ranged from 65.52% to 88.52%, corresponding to Sedative Use Disorder and Cannabis Use Disorder, respectively. For past SUDs, PPV values ranged from 53.85% to 89.08% for Hallucinogen Use Disorder and Alcohol Use Disorder. The NPV for current SUDs ranged from 87.39% to 98.21% for Alcohol Use Disorder and Sedative Use Disorder, respectively, and for past SUDs ranged from 83.33% to 98.33% in Alcohol Use Disorder and Amphetamine Use Disorder. In current MDs, PPV reached its lowest value at 54.05% for Substance-Induced Major Depressive Disorder and its highest at 70% for any Primary Psychotic Disorder. For past MDs, PPVs ranged from 56.67% to 72% for Substance-Induced Major Depressive Disorder and any Primary Psychotic Disorder, respectively. Current NPV in MDs ranged from 96.1% to 98.77% for Primary Major Depressive Disorder and Panic Disorder, whereas for past MDs, NPVs ranged from 94.33% for Primary Major Depressive Disorder to 98.34% for any Anxiety Disorder and ADHD (Table 5).

Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), and their respective confidence intervals for each disorder (current and past) obtained through the Spanish version of the PRISM 5, N=197.

| Diagnoses | Current diagnosis | Past diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPV (95% CI) | NPV 95% CI | PPV (95% CI) | NPV 95% CI | |

| Substance use disorders | ||||

| Alcohol | 88.37 (79.65–94.28) | 87.39 (79.74–92.93) | 89.08 (82.04–94.05) | 83.33 (73.19–90.82) |

| Hallucinogens | _a | 53.85 (25.13–80.78) | 96.74 (93.04–98.79) | |

| Cannabis | 88.52 (77.78–95.26) | 89.71 (83.33–94.26) | 87.06 (78.02–93.36) | 86.61 (78.87–92.31) |

| Cocaine | 82.14 (72.26–89.65) | 92.92 (86.53–96.89) | 78.95 (69.38–86.64) | 92.16 (85.13–96.55) |

| Heroin | 82.14 (63.11–93.94) | 94.00 (87.47–97.77) | 83.33 (70.71–92.08) | 97.22 (92.99–99.23) |

| Sedatives | 65.52 (45.67–82.06) | 98.21 (94.87–99.63) | 70.59 (52.52–84.90) | 96.93 (92.99–99.05) |

| Legal opioids | _a | |||

| Amphetamines | 58.82 (32.92–81.56) | 98.33 (95.21–99.65) | ||

| Depressive disorders | ||||

| Major depression, primary | 69.77 (53.87–82.82) | 96.10 (91.71–98.56) | 71.43 (57.79–82.70) | 94.33 (89.13–97.52) |

| Major depression, substance-induced | 54.05 (36.92–70.51) | 97.50 (93.72–99.31) | 56.67 (37.43–74.54) | 98.20 (94.84–99.63) |

| Persistent depression | ||||

| Bipolar disorder | ||||

| Hypomania | _a | |||

| Psychotic spectrum disorders | ||||

| Any psychotic diagnosis, primary | 70.00 (45.72–88.11) | 96.61 (92.77–98.75) | 72.00 (50.61–87.93) | 96.51 (92.56–98.71) |

| Any psychotic diagnosis, substance-induced | 66.67 (40.99–86.66) | 96.65 (92.85–98.75) | 69.23 (48.21–85.67) | 97.00 (93.31–99.04) |

| Anxiety disorders | ||||

| Panic | 66.67 (43.00–85.41) | 98.77 (95.64–99.85) | 65.52 (45.67–82.06) | 97.02 (93.19–99.03) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 65.52 (45.67–82.06) | 96.84 (92.95–98.92) | 65.52 (45.67–82.06) | 98.34 (95.23–99.66) |

| Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder | 62.50 (35.43–84.84) | 98.34 (95.23–99.66) | 62.50 (35.43–84.84) | 98.34 (95.23–99.66) |

| Personality disorder | ||||

| Antisocial | 64.29 (35.14–87.24) | 98.91 (96.11–99.87) | ||

| Borderline | 67.74 (48.63–83.32) | 96.99 (93.11–99.01) | ||

CI=confidence interval.

Interpretation of PPV and NPV: poor: <0.50; moderate: 0.50–0.69; good: 0.70–0.89; excellent: ≥0.90.

The evidence of reliability of the Spanish version of the PRISM-5 for diagnosing SUDs and MDs was evaluated in a sample of 197 participants, by comparing diagnoses obtained through the semi-structured interview with those derived from the LEAD method, serving as the reference standard. The results demonstrated strong reliability across diagnostic categories, further supporting the robustness of the PRISM for diagnosing comorbid psychiatric disorders in patients with SUDs.29,33 Furthermore, specificity values across diagnostic categories—including both SUDs and MDs—were consistently high, both for current and past diagnoses. Sensitivity, while also strong, tended to be somewhat lower in comparison. Nonetheless, these results should be interpreted with caution. As outlined in the Methods section, participants were recruited through a selective process, leading to a convenience sample with higher prevalence rates than those expected in the general population. This overrepresentation may influence sensitivity, specificity, as well as the positive and negative predictive values, all of which are known to be affected by prevalence. To mitigate this limitation, Cohen's Kappa was used as a more robust indicator of diagnostic agreement, given its relative independence from prevalence and its suitability for categorical assessments.

The evidence of reliability for current and past SUD diagnoses—including alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, sedative and amphetamine use disorders—was substantial to excellent. Similarly, the agreement for current and past MD diagnoses ranged from moderate to substantial, whether assessed individually or as grouped categories.

Compared to the earlier PRISM-IV Spanish version,33 this study features a larger sample size (197 vs. 105), providing broader diagnostic representation and enhanced statistical power. When analyzing individual diagnoses and comparing the results to those from PRISM-IV—also compared to the LEAD method—, the findings reveal similar levels of agreement, with only a few differences between both versions. These differences include a slight decrease in the evidence of reliability from excellent to substantial for current cocaine and heroin use disorders, and an improvement from moderate to substantial for past cannabis use disorder. Significant improvements were also noted in certain areas, including current and past alcohol abuse disorder—now categorized within the broader alcohol use disorder spectrum—, where reliability evidence improved from fair in PRISM-IV to substantial in PRISM-5. Similarly, current cannabis abuse, previously found to have poor reliability, is now encompassed within the broader category of cannabis use disorder, showing substantial reliability. For past hallucinogen use disorder and current amphetamine use disorder, PRISM-IV provided no results, whereas PRISM 5 includes data for these diagnoses with a substantial level of agreement.

The levels of agreement for MDs between PRISM-IV33 and PRISM-5 also remained largely stable when assessed against the LEAD method. However, a subtle decrease was observed in the reliability evidence of current panic disorder, which shifted from excellent to substantial. In contrast, marked improvements were seen for induced depression, with reliability evidence increasing from fair to moderate for current diagnoses and reaching substantial for past diagnoses.

When comparing the reliability evidence of the Spanish version of PRISM-5 with its English counterpart, notable differences emerge, specifically in their methodologies. The original PRISM-5 study included a larger sample size of 565 participants and used a test–retest method to assess reliability.29 Keeping these peculiarities in mind, both versions showed similar reliability evidence for current and past alcohol and cannabis use disorders, as well as for current cocaine and sedative disorders. However, the Spanish version scored higher levels of agreement for current and past hallucinogen and stimulant use disorders, as well as for current sedative use disorder.

Overall, these findings underscore both the consistency and the advancements in diagnostic reliability achieved with the PRISM-5, with most diagnostic categories maintaining comparable reliability evidence across versions. Notably, the new Spanish version of the PRISM-5, demonstrated at least moderate agreement across all diagnostic categories, with the majority achieving a substantial level of agreement compared to the reference standard. Since its validation in Spanish, PRISM-IV has been successfully applied in large samples, such as in the study by Mestre-Pinto et al.,31 where 827 substance users were assessed using this interview as the criterion standard.

One of the key strengths of our study lies in the instrument itself. The primary goal of developing an updated and computerized Spanish version of the PRISM interview was successfully achieved through the adaptation of diagnostic criteria to align with DSM-5 standards, combined with a meticulous process of translation, back-translation, and cultural adaptation. Compared to its paper-based counterpart, the computerized version of the PRISM-5 improves by reducing potential biases like selective memory, attribution, and exaggeration while detecting inconsistencies and enabling real-time modification. Moreover, it enhances reliability and efficiency by reducing human error, shortening administration time, and streamlines data management. Its user-friendly design makes it practical for clinicians and researchers, positioning the interview as an effective and innovative tool for diagnosis.

The diagnostic results obtained in our study using the PRISM-5 align closely with those previously reported by Dr. Hasin's group with the same instrument and by Dr. Torrens and colleagues using the earlier PRISM-IV in its Spanish version. The observed differences between the studies are minor, supporting the conclusion that both versions demonstrate a similar overall level of diagnostic accuracy. This is consistent with expectations, given that the updates introduced in PRISM-5 primarily reflect changes in diagnostic criteria between the DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5, while the structure and logic of the interview remain largely unchanged. Nonetheless, some specific distinctions emerged: PRISM-5 showed improved capacity to detect Substance-Induced Major Depressive Disorder, whereas the PRISM-IV appeared slightly more effective in identifying Panic Disorder.

Despite its strengths, this study is not without limitations. First, the LEAD method, chosen as the “gold standard” for comparison, has only been validated in two prior studies.35,42 While it has demonstrated good test-retest reliability evidence for most SUDs, its reliability for diagnosing comorbid disorders—such as major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, panic disorder, and borderline personality disorder—is comparatively lower. Moreover, the LEAD procedure does not incorporate a standardized interview format, which may contribute to variability in diagnostic outcomes, especially for internalizing disorders where symptom reporting can be inconsistent. These limitations are particularly relevant when interpreting kappa values, as discrepancies between PRISM-V and LEAD diagnoses may in some cases reflect inconsistencies in the reference standard rather than deficiencies in the instrument under validation. Thus, although the LEAD method offers a clinically informed synthesis of longitudinal data, its use as a benchmark should be interpreted with caution, particularly for psychiatric conditions with more heterogeneous presentations.

Another point worth highlighting is the moderate agreement observed between substance-induced and primary depressive disorders, which reflects the inherent diagnostic complexity in distinguishing these conditions. These difficulties may stem from overlapping symptomatology and the temporal variability of mood symptoms in individuals with active substance use. Such findings underscore the importance of integrating supplementary assessment strategies—such as collateral information, biomarkers, or prospective longitudinal follow-up—to more accurately determine the etiological nature of depressive symptoms in dual diagnosis populations.

Another limitation lies in the low prevalence of certain diagnoses in our sample, a result of the specific healthcare setting from which patients were recruited. To address this issue, a convenience sampling approach was used to maximize the inclusion of underrepresented diagnoses. However, in some cases, grouping clinically similar diagnoses became necessary to achieve adequate sample sizes for analysis. Also, the number of women was higher than that of men, which could have influenced the results and the evidence gathered regarding the reliability and validity evidence of the diagnostic inferences based on the instrument's scores. This imbalance should be considered when interpreting the findings, especially given the potential gender-related differences in dual disorders presentation and diagnosis. For similar reasons, stratified analyses by age or sex were not conducted. Subdividing the sample by demographic variables would have resulted in significantly underpowered and heterogeneous subgroups, limiting the statistical robustness and interpretability of findings. This decision aligns with the analytic approach applied elsewhere in the study, where low-frequency diagnoses were grouped to maintain sufficient case numbers for reliable analysis. Finally, it is important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with the end of the recruitment period, negatively impacting the final sample size.

As a consequence of these constraints, we were also unable to conduct stratified analyses of diagnostic patterns by gender and age groups. Although we initially considered this approach, the resulting subgroup cell sizes were insufficient to yield statistically reliable or representative results. Future studies with larger and more balanced samples will be better positioned to explore how diagnostic prevalence and clinical presentation may vary across gender and age. Incorporating these variables could provide a more nuanced understanding of mental health trajectories and support the development of more tailored interventions.

Future studies should aim to address the limitations identified, particularly by ensuring a more balanced representation across all diagnoses. Also, in addition to the quantitative measures of reliability evidence presented in this study, future research could benefit from the inclusion of qualitative feedback from both clinicians and patients. Understanding users’ perspectives on the PRISM-V interview—such as its clarity, length, perceived usefulness, and cultural appropriateness—could provide valuable insights for further refining the tool and optimizing its clinical implementation. Collecting narrative data from clinicians who administer the interview and from patients who complete it may help identify potential barriers, enhance user engagement, and ensure the instrument's adaptability across diverse healthcare contexts. This complementary approach would support a more holistic evaluation of the instrument's practical relevance and acceptability in real-world settings.

Despite these challenges and limitations, this study provides strong evidence supporting the utility of the PRISM-5 interview in diagnosing SUDs and comorbid psychiatric conditions. With substantial to excellent reliability evidence for most diagnoses, PRISM-5 probes to be a valuable and robust tool in clinical and research settings, also in its Spanish version, further establishing the interview as rigorous instrument for advancing the assessment and understanding of DDs.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

FundingThis work was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), the European Regional Development Fund and the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan, and Results-oriented Cooperative Research Networks in Health (RICORS), Spain [grant numbers RD21/0009/0001, RD21/0009/0029, RD24/0003/0001, RD24/0003/0015, RD24/0003/0023] and the PI14/00178 project.

None.

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants who took part in the study.

In memory of Marina Comín, whose contribution and dedication to this work were essential.