Many studies have found that hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis abnormalities are related to the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder (MDD) and cognitive functioning. Our aim was to assess the influence of genetic polymorphisms and methylation levels in three different promoter regions throughout the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) gene NR3C1 on cognitive performance in MDD. Plausible interactions with childhood adversity and mediation relationships between genetic and epigenetic variables were explored.

Materials and methodsThe sample included a total of 64 MDD patients and 82 healthy controls. Child maltreatment and neurocognitive performance were assessed in all participants. HPA negative feedback was analyzed using the dexamethasone suppression test after the administration of 0.25mg of dexamethasone. A total of 23 single-nucleotide polymorphisms were genotyped, and methylation levels at several CpGs in exons 1D, 1F and 1H of the GR gene were measured.

ResultsResults show that, beyond the influence of other covariables, NR3C1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms and methylation levels predicted performance in executive functioning and working memory tasks. No significant interactions or mediation relationships were detected.

ConclusionsResults suggest that genetic variations and epigenetic regulation of the GR gene are relevant factors influencing cognitive performance in MDD and could emerge as significant biomarkers and therapeutic targets in mood disorders and other stress-related disorders.

Cognitive deficits are commonly observed in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), especially associated with tasks involving memory and executive functioning.1 Genetic factors have demonstrated to be able to influence the risk and clinical presentation of most major mental disorders, including MDD, which is estimated to have a heritability nature in approximately 50% of the cases.2 Despite the existing knowledge, genome-wide association studies in MDD have yielded a scarcity of significant results and replication of findings is rare.3,4 It has been proposed that MDD clinical heterogeneity and multifactorial nature might account for such inconsistent results. Several strategies have been proposed to overcome these limitations, among which the use of underlying biological and clinical endophenotypes has been increasingly emphasized. This approach is deemed more robust since the relationship between underlying biological mechanisms and genetic variations is likely to be stronger.

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is the primary stress-response hormonal system in humans. Dysregulations in HPA axis activity lead to impaired cortisol levels, thus yielding inadequate responses to stressors; this relationship has been involved in the pathophysiology of several mental disorders. Most studies of MDD have shown a pattern of hypercortisolemia and glucocorticoid resistance reflected by increased basal cortisol levels, reduced reactivity to psychosocial stress and reduced cortisol suppression in pharmacological challenge tests.5 Moreover, some alterations in HPA axis activity have been associated with specific clinical differences within MDD patients, such as psychotic6 or cognitive symptoms.7

The HPA axis regulates the production of cortisol, which is released from the adrenal gland and binds to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs). Cortisol has a high affinity for MRs, which are localized predominantly in the hippocampus and are responsible for the tonic influences of cortisol. On the other hand, cortisol has a lower affinity for the GR, which is more widely distributed throughout the brain and is responsible for the activation of the regulatory feedback mechanism of the HPA axis in areas such as the hypophysis or the amygdala (De Kloet and Reul, 1987). Glucocorticoid resistance, defined as the difficulty in downregulating cortisol activity after exposure to a stressful situation, is related to a loss of sensitivity of the GR to cortisol, thus causing the negative feedback mechanism to become inefficient. This phenomenon has been linked to genetic and epigenetic variations in the GR gene (NR3C1).8,9

Many studies have analyzed the effects of genetic variations within NR3C1. This gene is located on chromosome 5q31-32 and is a member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors. Five functional polymorphisms in NR3C1 with a documented effect on GR sensitivity have been previously documented10 (Supplementary Table S1). Some of these genetic polymorphisms (SNPs) have also been associated with changes in HPA reactivity to stressful events in healthy individuals.11 Other studies in healthy populations have shown that some NR3C1 SNPs may influence working memory; however, other groups have been unable to replicate these results, and it has been suggested that the effects of SNPs in NR3C1 on cognition might only be observed in the presence of highly stressful situations.12 This hypothesis is supported by previous studies showing that the influence of NR3C1 variants on HPA axis functioning is dependent on the presence of stressful life events.13

Our group conducted a systematic review on the effects of variations in HPA-related genes on cognitive performance in mood and psychotic disorders that revealed a paucity of studies including NR3C1 SNPs and an absence of studies including epigenetic data.14 All studies identified were conducted with samples from patients with affective disorders. The most thorough study – considering the variants in NR3C1 and cognitive tasks included – was the one conducted by Keller et al.; they found that NR3C1 variants predicted performance in tasks involving attention and executive functions, and this effect remained significant after adjusting for HPA axis measures.15 Other studies showed an association between ER22/23EK, a known NR3C1 functional polymorphism, and better performance in attention tasks16 and a nominal association suggesting an influence on memory tasks.17

Regarding epigenetic studies, epigenome-wide studies of MDD have found that methylation variations could become a useful biomarker for MDD.18,19 Animal models have shown that hypermethylation of NR3C1 promoter regions is linked to decreased glucocorticoid feedback sensitivity in rats exposed to stressful life experiences.20 In humans, the NR3C1 gene includes 8 coding exons (2–9) and 9 non-coding first exons (1A–1J) acting as alternate promoters.21 Studies in humans have consistently reported that exposure to stress and prolonged exposure to high GC levels can trigger methylation changes in relevant areas within NR3C1.22 Most research linking NR3C1 methylation levels and stressful situations or psychiatric disorders has focused on exon 1F. Hypermethylation at exon 1F has been previously associated with child maltreatment and certain psychopathological measures, such as depressive and anxiety symptomatology, emotional lability-negativity or externalizing behaviur.23 However, the NR3C1 promoter region is a complex structure with up to 9 alternative non-coding exons in promoter 1, which have received far less attention, as shown in the thorough review by Palma-Gudiel et al.21 This same group subsequently proved that hypermethylation in glucocorticoid responsive elements (GRE) in other exons, such as 1D, was associated with an increase in familial tendency to anxious-depressive disorders and poorer hippocampal connectivity.24 Furthermore, specific regions of both exon 1D and 1H have been associated with schizophrenia in a sex specific manner25 and exon 1H was shown to be hypermethylated in a sample of chronic alcohol drinkers26 while it was hypomethylated in samples of patients with childhood abuse or bulimia nervosa with comorbid borderline personality disorder.21 These results suggest a very relevant influence of differential methylation in promoter areas other than exon 1F.

We hypothesized that both SNPs and methylation levels in the NR3C1 gene might influence cognitive performance in MDD in those domains previously associated with NR3C1 variations, including attention, working memory and executive functioning, and that this relationship might be tapered by external factors, such as a history of childhood adversity. Our objective was to analyze the impact of genetic polymorphisms throughout the NR3C1 gene, with a special focus on previously identified functional SNPs, as well as methylation levels in 3 different promoter regions (exons 1D, 1F and 1H) on cognitive performance in a sample of patients with MDD and healthy controls. We also aimed to explore possible interactions with childhood adversity and potential mediation relationships between genetic and epigenetic variables and their role in cognition.

Materials and methodsStudy sampleThe sample included a total of 64 MDD patients (72% women; mean age, 57.1±1.3 years) diagnosed following the DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and 82 healthy controls (HCs) (60% women; mean age, 50.6±1.5 years). MDD patients were recruited from the Psychiatry Department at Bellvitge University Hospital (Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain), while HCs were recruited from the same geographic region through advertisements. All participants were unrelated to each other and of Iberian Peninsula ancestry.

Exclusion criteria were age younger than 18 years, non-white ethnicity, a diagnosis of other psychiatric disorders including substance abuse or dependence (except nicotine), neurological disorders including dementia, intellectual disability, severe medical conditions, electroconvulsive therapy in the previous year, pregnancy or puerperium, and corticosteroid treatment in the previous 3 months. The sample partially overlaps that used in former studies that explored different hypotheses.27,28 Research protocol (PR81/10) was approved by Bellvitge University Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CEIC) and all participants gave their prior written informed consent after having received a full explanation of the study.

Clinical assessmentPatients were interviewed by an experienced psychiatrist and all patients met DSM-IV-TR criteria for MDD, which was confirmed relying on the Spanish version of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview.29 Healthy controls (HCs) had scores <7 on the 28-item Spanish adaptation of the Goldberg General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28)30 and showed no past medical history of psychiatric disorders.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables, substance use, and treatment were assessed using a semi-structured interview administered by an experienced clinician. Since benzodiazepine treatment affects cognition, diazepam equivalent doses were calculated for patients under treatment with any benzodiazepine drug.

The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) was used to assess depression severity.31 History of child maltreatment was assessed by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ),32 a self-report instrument that retrospectively explores child abuse and neglect and obtains a total score and 5 subscores of childhood trauma: sexual, physical and emotional abuse, and physical and emotional neglect.

Neuropsychological assessmentThe Spanish version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to screen for dementia. The following neuropsychological tests were administered to all participants to assess performance in attention, working memory and executive functions:

Attention: Trail Making Test Part A (TMT-A) and Continuous Performance Test – Identical Pairs (CPT-IP).

Working memory: Corsi Block-Tapping Test (CBTT) and Letter-Number Span (LNS).

Executive functions: Trail Making Test Part B (TMT-B); Neuropsychological Assessment Battery® Mazes (NAB-Mazes) and Stroop test (direct subscores for words-colours (WC) and interference).

In all tests, higher scores showed better cognitive performance with the exceptions of TMT-A and TMT-B, where the outcome measure is the number of seconds needed to perform the task; thus, higher scores reflected worse cognitive performance.

Salivary cortisol measurementsThe dexamethasone suppression test (DST) is used to assess the functionality of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis by measuring the cortisol response following the administration of dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid. Dysregulation of the HPA axis negative feedback in MDD patients have been most commonly assessed using this test.

Saliva sample collection and cortisol measurement were performed as in former studies from our group.25 Saliva samples were collected using Salivette® (Sarstedt AG & Co., Nümbrecht, Germany) containers. Two saliva samples were considered to calculate the dexamethasone suppression test ratio (DSTR): patients were instructed to collect a first-morning salivary sample at 10 a.m. (day 0), take 0.25mg of dexamethasone at 11 p.m. on the same day (day 0) and collect another salivary sample at 10 a.m. the day after (day 1). DSTR was defined as the ratio of basal cortisol (at 10 a.m. before dexamethasone)/cortisol at 10 a.m. post dexamethasone. Very low-dose of dexamethasone for the DST was chosen to allow us to detect subtle changes in HPA axis reactivity, which cannot be easily detected with a high dose DST.33

SNP selection and genotypingBlood samples were obtained from all participants at the time of neuropsychological assessment. The Tagger tool of Haploview v.4.2 45 was used to select tagSNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2>0.7) with the remaining SNPs at minor allele frequency (MAF) >10% from the HapMap phase III European samples. Functional SNPs, including rs10052957 (TthIIII), rs6189 and rs6190 (ER22/23EK), rs41423247 (BclI) and rs6198 (9β) were prioritized as tagSNPs. Overall, a total of 23 SNPs were selected (Supplementary Table S2).

Genotyping of the selected SNPs was performed using the MassARRAYiPLEX platform (Agena Bioscience, formerly Sequenom, Inc.; San Diego, CA, United States). The genotyping assays were performed at the genotyping facilities of the “Centro Nacional de Genotipado” in the Santiago de Compostela Node (CeGen).

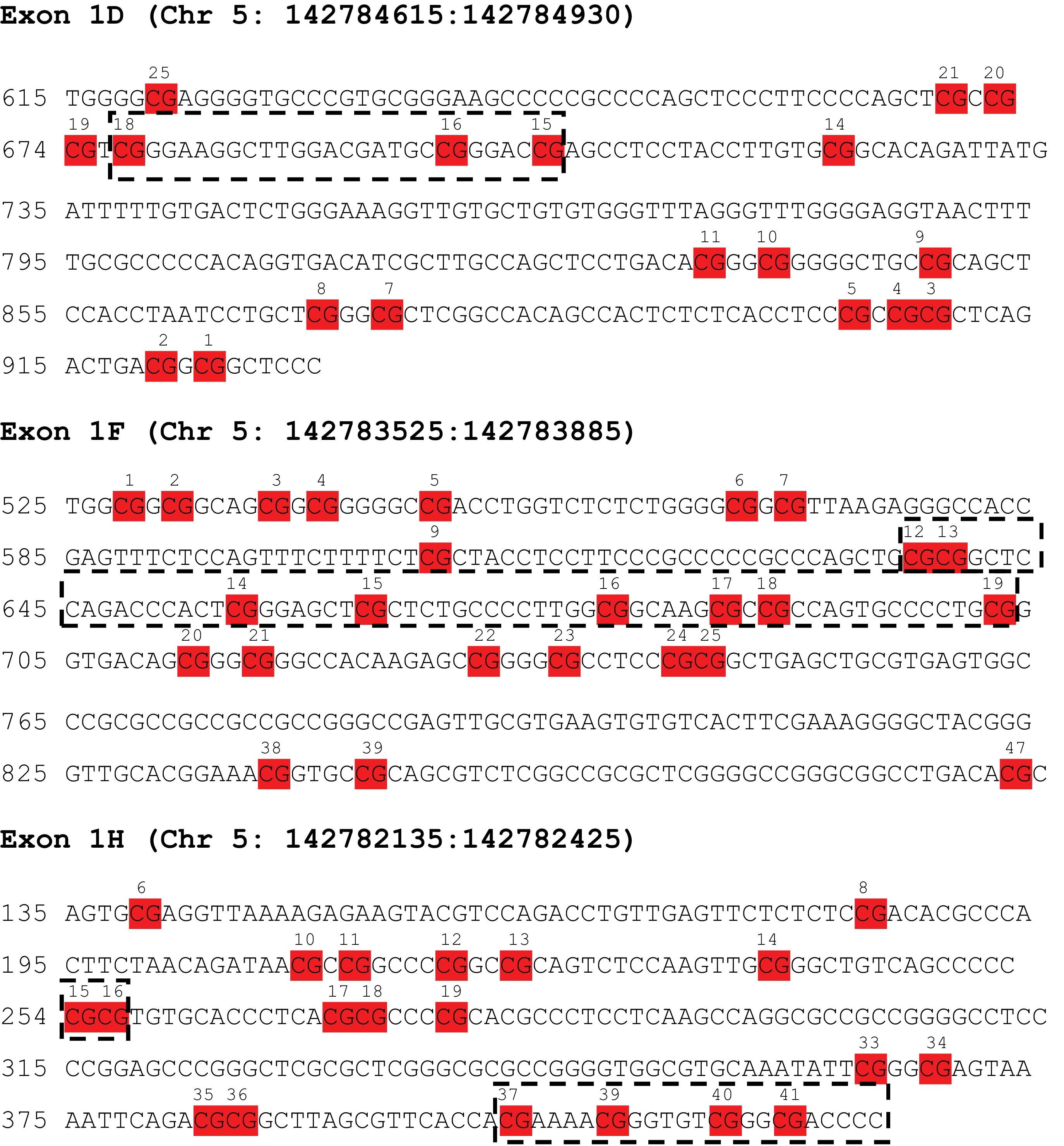

DNA methylation analysisExons 1D, 1F and 1H were selected for the methylation analyses due to previous evidence of an association between methylation levels at these sites and different psychiatric phenotypes.

One assay was used to cover each region; for exon 1D, the assay covered chr5: 142784531–142784950; for exon 1F, the assay covered chr5: 142783503–142783908; and for exon 1H, the assay covered chr5: 142782047–142782472 (hg19). CpG sites analyzed in each region can be found in Table 3 of the supplementary data (Table S3).

DNA purification, bisulfite treatment, and quantitative DNA methylation analysis using the MassArray platform of SEQUENOM were performed as described in previous works.24 Briefly, primers were designed using MethPrimer (http://www.urogene.org/methprimer/). To obtain an appropriate product for in vitro transcription, prevent abortive cycling or balance the PCR primer length, primers were tagged (forwards primer tag: cagtaatacgactcactatagggagaaggct, reverse primer tag: aggaagagag). Primer sequences can be found in Table 3 of the supplementary data (Table S3).

Statistical analysisData processing and all analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, IBM, USA). Chi-squared (dichotomous variables) and Student's t tests (continuous variables) were used for descriptive analyses. Since all cortisol measurements showed positive skewness, as in our previous work,25 we used the power transformation proposed by Miller and Plessow.34 DSTR calculated with untransformed cortisol measures is shown in the tables. However, DSTR calculated with transformed cortisol measures was used in the multivariate analyses. Cognitive variables that showed a skewed distribution were log transformed (ln) to approximate normality, which was the case for 2 cognitive tests (TMT-A and TMT-B). Correlations between NR3C1 methylation levels and methylation levels in other genes analyzed in previous works27,28 (BDNF and FKBP5) were further examine to exclude any possible confounding factors. Partial correlation analyses adjusted by age, gender, and years of education were used to explore the relationship between methylation measures and cognitive performance. We conducted a stratified analysis by diagnosis (HCs vs MDD).

Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to study the impact of NR3C1 SNPs on cognitive performance in both groups (HC and MDD). Following the methodology of former studies15 and to avoid imposing possible biases, a forward regression approach was used to study dependent variables. This method allows the detection of the most important factors influencing the dependent variables. Variable entry was set at 0.05, and variable removal was set at 0.10. Dependent variables were the results in each cognitive test. Independent variables included age, sex, years of education, MDD diagnosis, child maltreatment scores, daily benzodiazepine use, DSTR and all SNPs genotyped. Further multiple regression analyses using the same methodology as previously described were performed to analyse the association between NR3C1 methylation at promoter sites and cognitive performance. These regressions included methylation levels at each CpG site instead of the SNPs.

Additionally, the influence of interactions between NR3C1 polymorphisms and methylation variables with scores of the child maltreatment questionnaire on cognitive domains was explored as well. To do so, further multiple regression analyses were performed only including variables with a statistically significant association with the study cognitive test in former analyses, including the genetic or epigenetic variable, the CTQ scores and the interaction between the genetic or epigenetic variable and CTQ scores.

All tests were two-sided. To account for the large number of comparisons, and following the same methodology as in former studies,15 the overall significance level of the final forward linear regression models was set at P≤0.005. Subsequent analysis of the contribution of each independent variable were set at a significance level of P≤0.05. Multicollinearity between included variables was ruled out by measuring the Variance inflation factor (VIF) in the regression analyses. All VIF values for independent variables in the regression analyses were <3.

A further stratified analysis by the diagnostic group of the association between methylation values and cognition was performed to explore the existence of significant differences in this relationship depending on diagnostic category.

Finally, mediation analysis was performed to determine whether methylation variables were involved the relationship between SNPs and neurocognitive variables. This analysis was performed with the PROCESS macro of SPSS version 21.0 developed by Hayes.35 Additionally, bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals were used. Results were considered statistically significant when the bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals did not contain zero. We analyzed the mediation of SNPs and methylation variables that had shown a significant association with the study cognitive variable in the above-mentioned linear regression analyses.

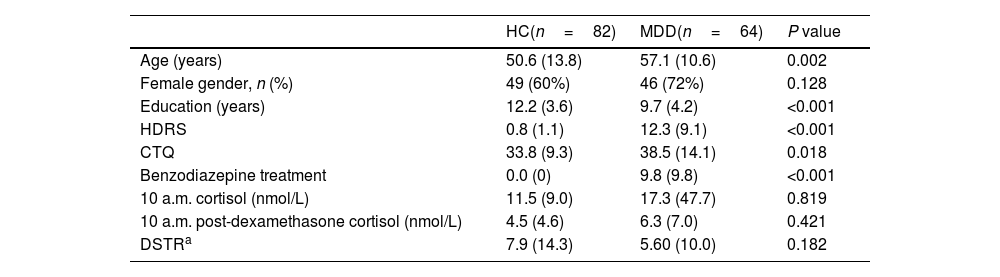

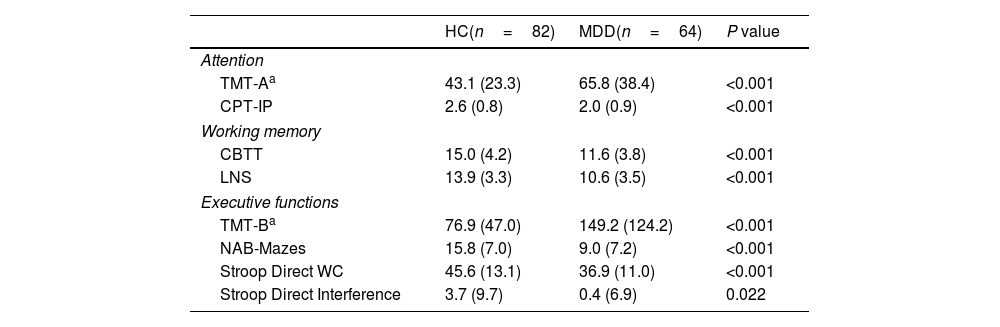

ResultsUnivariate analysisDemographic, clinical and HPA axis-related variables are shown in Table 1. As expected, MDD patients showed higher HDRS and CTQ scores vs HCs. No significant differences were observed in cortisol measures between HC and MDD (Table 1 shows raw cortisol values, all further analysis were performed using the transformed variables after Miller and Plessow power transformation). Regarding neurocognitive functioning, MDD patients showed worse cognitive performance than HCs in all cognitive domains (Table 2).

Demographic and clinical data of the study sample.

| HC(n=82) | MDD(n=64) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.6 (13.8) | 57.1 (10.6) | 0.002 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 49 (60%) | 46 (72%) | 0.128 |

| Education (years) | 12.2 (3.6) | 9.7 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| HDRS | 0.8 (1.1) | 12.3 (9.1) | <0.001 |

| CTQ | 33.8 (9.3) | 38.5 (14.1) | 0.018 |

| Benzodiazepine treatment | 0.0 (0) | 9.8 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| 10 a.m. cortisol (nmol/L) | 11.5 (9.0) | 17.3 (47.7) | 0.819 |

| 10 a.m. post-dexamethasone cortisol (nmol/L) | 4.5 (4.6) | 6.3 (7.0) | 0.421 |

| DSTRa | 7.9 (14.3) | 5.60 (10.0) | 0.182 |

HC, healthy controls; MDD, major depressive disorder; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; DSTR, dexamethasone suppression test ratio.

All variables expressed as mean (SD), or n (%). Missing data: DSTR (5.5%).

Untransformed cortisol values are shown here.

P values calculated using transformed values.

Neurocognitive results of the study sample.

| HC(n=82) | MDD(n=64) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention | |||

| TMT-Aa | 43.1 (23.3) | 65.8 (38.4) | <0.001 |

| CPT-IP | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Working memory | |||

| CBTT | 15.0 (4.2) | 11.6 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| LNS | 13.9 (3.3) | 10.6 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| Executive functions | |||

| TMT-Ba | 76.9 (47.0) | 149.2 (124.2) | <0.001 |

| NAB-Mazes | 15.8 (7.0) | 9.0 (7.2) | <0.001 |

| Stroop Direct WC | 45.6 (13.1) | 36.9 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Stroop Direct Interference | 3.7 (9.7) | 0.4 (6.9) | 0.022 |

All variables expressed as mean (SD).

HC, healthy controls; MDD, major depressive disorder; TMT-A, Trail Making Test Part A; CPT-IP, Continuous Performance Test – Identical Pairs; CBTT, Corsi Block-Tapping Test; LNS, Letter-Number Span; TMT-B, Trail Making Test Part B; NAB-Mazes, Neuropsychological Assessment Battery® Mazes.

Missing data: TMT-A (1.4%); CPT-IP (12.3%); CBTT (1.4%); LNS (4.1%); TMT-B (4.1%); NAB-Mazes (2.1%); Stroop Direct WC (1.4%); Stroop Direct Interference (1.4%).

The mean methylation values at each CpG site are shown in Table S4 of the supplementary data. Methylation levels were generally higher in HCs vs MDD patients, with significant differences in CpG 3.4.5, CpG 14 and CpG 15.16 of exon 1D; CpG 1.2, CpG 3.4.5 and CpG 38.39 of exon 1F; and CpG 6, CpG 14, and CpG 37 of exon 1H. However, in a few locations, MDD patients showed higher methylation levels than HCs, with significant differences in CpG 10.11.12.13 and CpG 15.16 of exon 1H. No significant correlations were observed between methylation levels of NR3C1 and BDNF, but up to 3 different NR3C1 sites had statistically significant correlations with specific FKBP5 CpGs methylation levels (Supplementary Table S5).

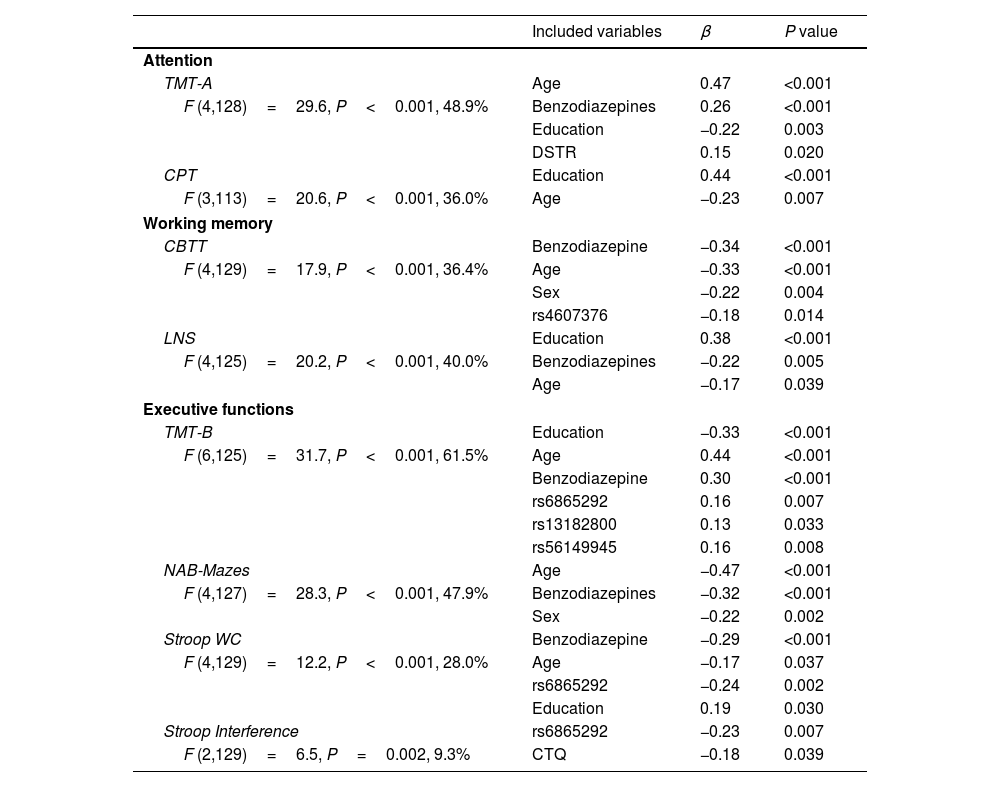

Genetic analysisAll genotyped polymorphisms were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and had call rates >90%. Results of forward linear regression analyses including NR3C1 SNPs as the main independent variables are shown in Table 3. Significant associations were mainly found with executive functioning tasks; TMT-B results were predicted by rs6865292, rs13182800 and rs56149945, while Stroop Direct WC and Interference results were predicted by rs6865292 beyond the contribution of other included variables. Regarding working memory tasks, CBTT scores were associated with rs4607376. No significant associations were found between performance in attention tasks and NR3C1 SNPs. A significant association was observed between the DSTR and TMT-A results, in which higher DSTR values (higher GR sensitivity) were associated with better results in this attention task. MDD diagnosis was significantly associated with poorer results in attention (CPT), working memory (LNS) and executive functioning tasks (NAB-Mazes and Stroop Interference).

Results of forward linear regression models including NR3C1 SNPs.

| Included variables | β | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention | |||

| TMT-A | Age | 0.47 | <0.001 |

| F (4,128)=29.6, P<0.001, 48.9% | Benzodiazepines | 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Education | −0.22 | 0.003 | |

| DSTR | 0.15 | 0.020 | |

| CPT | Education | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| F (3,113)=20.6, P<0.001, 36.0% | Age | −0.23 | 0.007 |

| Working memory | |||

| CBTT | Benzodiazepine | −0.34 | <0.001 |

| F (4,129)=17.9, P<0.001, 36.4% | Age | −0.33 | <0.001 |

| Sex | −0.22 | 0.004 | |

| rs4607376 | −0.18 | 0.014 | |

| LNS | Education | 0.38 | <0.001 |

| F (4,125)=20.2, P<0.001, 40.0% | Benzodiazepines | −0.22 | 0.005 |

| Age | −0.17 | 0.039 | |

| Executive functions | |||

| TMT-B | Education | −0.33 | <0.001 |

| F (6,125)=31.7, P<0.001, 61.5% | Age | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Benzodiazepine | 0.30 | <0.001 | |

| rs6865292 | 0.16 | 0.007 | |

| rs13182800 | 0.13 | 0.033 | |

| rs56149945 | 0.16 | 0.008 | |

| NAB-Mazes | Age | −0.47 | <0.001 |

| F (4,127)=28.3, P<0.001, 47.9% | Benzodiazepines | −0.32 | <0.001 |

| Sex | −0.22 | 0.002 | |

| Stroop WC | Benzodiazepine | −0.29 | <0.001 |

| F (4,129)=12.2, P<0.001, 28.0% | Age | −0.17 | 0.037 |

| rs6865292 | −0.24 | 0.002 | |

| Education | 0.19 | 0.030 | |

| Stroop Interference | rs6865292 | −0.23 | 0.007 |

| F (2,129)=6.5, P=0.002, 9.3% | CTQ | −0.18 | 0.039 |

β, standardized beta coefficient; TMT-A, Trail Making Test Part A; CPT-IP, Continuous Performance Test – Identical Pairs; CBTT, Corsi Block-Tapping Test; LNS, Letter-Number Span; TMT-B, Trail Making Test Part B; NAB-Mazes, Neuropsychological Assessment Battery® Mazes; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

Statistics for the full model are presented here.

Variables included in the models: age, sex, years of education, depression severity, childhood trauma questionnaire, daily benzodiazepines use, DSTR and all SNPs genotyped.

We analyzed the correlation between methylation variables and neuropsychological performance. The correlation heat map of these partial correlation analyses stratified by diagnosis is included in Fig. S1 of the supplementary data.

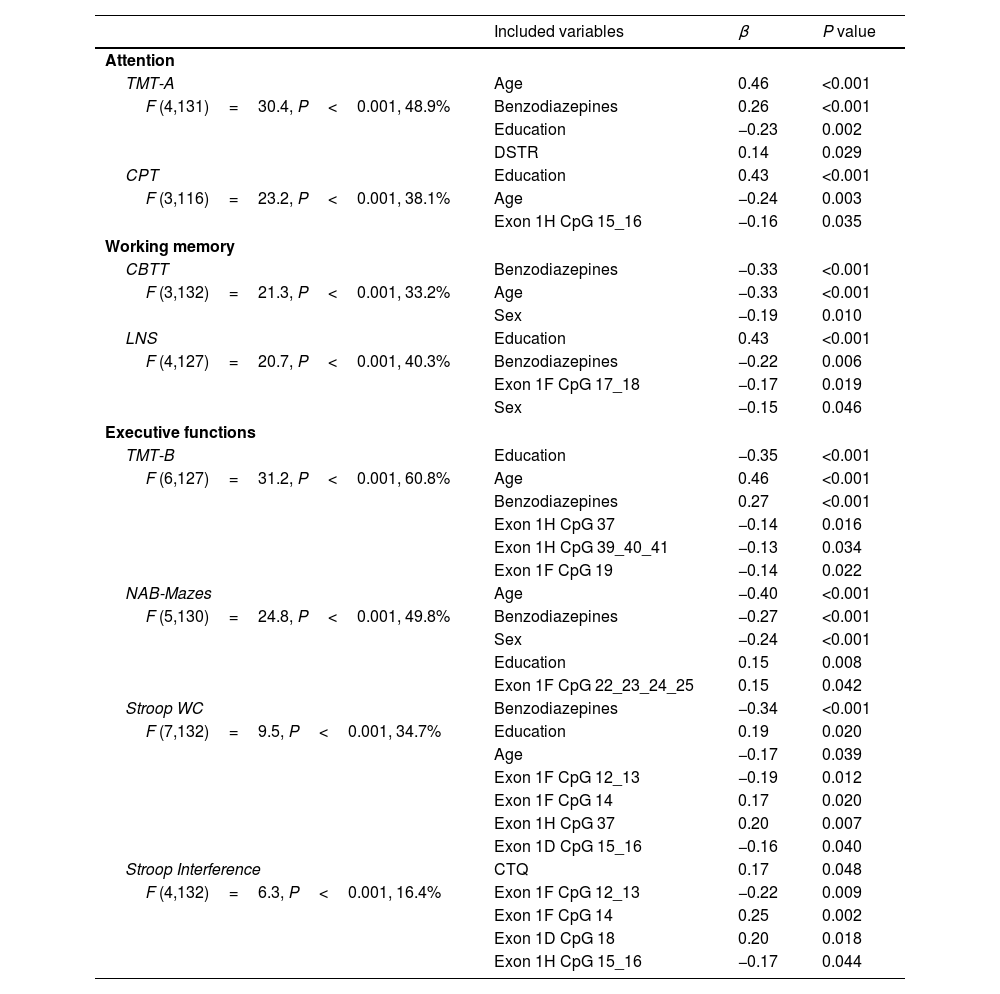

Results of forward linear regression analyses including NR3C1 methylation levels in each CpG site of exons 1D, 1F and 1H as the main independent variables are shown in Table 4. Only 1 significant association between methylation variables and working memory performance was detected, and the association observed was between results in the LNS test and methylation level at exon 1F CpG 17_18. Similar to results of genetic analysis, most significant associations were found when analyzing executive functioning tasks. TMT-B results were associated with 2 exon 1H sites (CpG 37 and CpG 39_40_41) and 1 exon 1F site (CpG 19); NAB-Mazes results were associated with 1 site in exon 1F (CpG 22_23_24_25); Stoop WC results were associated with 2 exon 1F sites (CpG 12_13 and CpG 14), 1 exon 1H site (CpG 37) and 1 exon 1D site (CpG 15_16); and finally, the Stroop Interference results were associated with 2 exon 1F sites (CpG 12_13 and CpG 14) and 1 exon 1D site (CpG 18). In most observed associations, higher methylation levels predicted worse results in the cognitive tests included. However, in some locations (Exon 1F CpG 14, Exon 1D CpG 18 and Exon 1H CpG 22_23_24_25 and CpG 37), an inverse relationship was observed, and higher methylation at these sites was associated with better cognitive performance. Interestingly, most reported significant associations are concentrated in certain areas of the promoter regions as shown in Fig. 1. Similar to genetic analysis, MDD diagnosis was still significantly associated with poorer results in attention (CPT), working memory (LNS) and executive functioning tasks (NAB-Mazes and Stroop Interference).

Results of forward linear regression models including NR3C1 methylation variables.

| Included variables | β | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention | |||

| TMT-A | Age | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| F (4,131)=30.4, P<0.001, 48.9% | Benzodiazepines | 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Education | −0.23 | 0.002 | |

| DSTR | 0.14 | 0.029 | |

| CPT | Education | 0.43 | <0.001 |

| F (3,116)=23.2, P<0.001, 38.1% | Age | −0.24 | 0.003 |

| Exon 1H CpG 15_16 | −0.16 | 0.035 | |

| Working memory | |||

| CBTT | Benzodiazepines | −0.33 | <0.001 |

| F (3,132)=21.3, P<0.001, 33.2% | Age | −0.33 | <0.001 |

| Sex | −0.19 | 0.010 | |

| LNS | Education | 0.43 | <0.001 |

| F (4,127)=20.7, P<0.001, 40.3% | Benzodiazepines | −0.22 | 0.006 |

| Exon 1F CpG 17_18 | −0.17 | 0.019 | |

| Sex | −0.15 | 0.046 | |

| Executive functions | |||

| TMT-B | Education | −0.35 | <0.001 |

| F (6,127)=31.2, P<0.001, 60.8% | Age | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| Benzodiazepines | 0.27 | <0.001 | |

| Exon 1H CpG 37 | −0.14 | 0.016 | |

| Exon 1H CpG 39_40_41 | −0.13 | 0.034 | |

| Exon 1F CpG 19 | −0.14 | 0.022 | |

| NAB-Mazes | Age | −0.40 | <0.001 |

| F (5,130)=24.8, P<0.001, 49.8% | Benzodiazepines | −0.27 | <0.001 |

| Sex | −0.24 | <0.001 | |

| Education | 0.15 | 0.008 | |

| Exon 1F CpG 22_23_24_25 | 0.15 | 0.042 | |

| Stroop WC | Benzodiazepines | −0.34 | <0.001 |

| F (7,132)=9.5, P<0.001, 34.7% | Education | 0.19 | 0.020 |

| Age | −0.17 | 0.039 | |

| Exon 1F CpG 12_13 | −0.19 | 0.012 | |

| Exon 1F CpG 14 | 0.17 | 0.020 | |

| Exon 1H CpG 37 | 0.20 | 0.007 | |

| Exon 1D CpG 15_16 | −0.16 | 0.040 | |

| Stroop Interference | CTQ | 0.17 | 0.048 |

| F (4,132)=6.3, P<0.001, 16.4% | Exon 1F CpG 12_13 | −0.22 | 0.009 |

| Exon 1F CpG 14 | 0.25 | 0.002 | |

| Exon 1D CpG 18 | 0.20 | 0.018 | |

| Exon 1H CpG 15_16 | −0.17 | 0.044 | |

β, standardized beta coefficient; TMT-A, Trail Making Test Part A; CPT-IP, Continuous Performance Test – Identical Pairs; CBTT, Corsi Block-Tapping Test; LNS, Letter-Number Span; TMT-B, Trail Making Test Part B; NAB-Mazes, Neuropsychological Assessment Battery® Mazes; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

Statistics for the full model are presented here.

Variables included in the models: age, sex, years of education, depression severity, childhood trauma questionnaire, daily benzodiazepines use, DSTR and methylation levels at each CpG site.

Results from the stratified analysis by diagnostic group can be found in Supplementary Table S6. Overall, there seem to be a few more significant associations between methylation variables in the MDD vs the HC group (22 vs 16).

Interaction and mediation analysisNo statistically significant results of the interaction analysis between genetic and epigenetic variables with CTQ score analysis on cognition were found. Additionally, no significant mediation relationships between NR3C1 SNPs and methylation values were detected.

DiscussionIn this study, we analyzed the influence of NR3C1 genetic and epigenetic variations on attention, working memory and executive functioning in a sample including MDD patients and HCs. Our main findings include statistically significant associations between genetic and epigenetic variations in the NR3C1 gene and cognitive performance, especially in tasks involving executive functions, regardless of the influence of the activity of the HPA axis negative feedback or moderating external factors such as a history of childhood trauma.

In our results, only 1 attention-related cognitive task (TMT-A) showed a significant association with measures of activity of the HPA axis negative feedback (DSTR). The relationship between DSTR and cognition is unclear, and there is evidence suggesting a relationship between cortisol suppression through dexamethasone administration and differences in executive functioning36,37; however, other groups have reported negative findings when studying this association.38 There is no previous evidence of an association between the activity of HPA axis negative feedback and attention capacity in patients with MDD. Our results suggest that the well-documented effect of cortisol on cognitive functioning in both the healthy population and MDD is not explained by variations in the reactivity of the HPA axis negative feedback, as cortisol only showed a mild association with attention measures. This relationship should be further examined in future studies.

The focus of interest of this work was to explore the relationship between genetic and epigenetic variations in the NR3C1 gene and cognitive variables. Several significant associations have been identified in this regard. Regarding the genetic polymorphisms of NR3C1, rs4607376 was seen to predict results in a working memory task. This polymorphism has never been previously associated with any mental health disorder, having only been associated in the past with a differential risk of presenting systemic lupus erythematosus in a Chinese population.39 Several NR3C1 SNPs have shown significant associations with performance in executive functioning tasks. As far as we know, there is no previous evidence of an association between the SNPs rs6865292 and rs13182800 and any mental health or cognitive phenotype, making this the first evidence of a possible influence of these variations on cognitive performance in MDD. Of note, rs6865292 shows a significant association with 3 different executive functioning tasks, reinforcing the relevant role of this variation in this cognitive domain. On the other hand, rs56149945 – also known as N363S or rs6195 – is a functional SNP that has been shown to influence GR sensitivity to dexamethasone.40 Interestingly, a recent study by Van der Auwera et al. conducted in a large cohort, showed a direct association between verbal memory and genetic variations in SNP rs56149945 as well as to NR3C1 gene expression and cortisol levels.41 Their results, as well as ours, suggest a direct influence of rs56149945 on cognitive performance, probably across different cognitive domains, including verbal memory and executive functioning.

Regarding the relationship between NR3C1 epigenetic regulation through promoter region methylation and cognitive performance, our results provide several statistically significant associations. Similar to the genetic analysis results, most significant associations are related to executive functioning tasks. Remarkably, the reported significant associations focus on specific areas of the promoter regions (as shown in Fig. 1). For example, in Exon 1F, most associations are observed between CpG 12 and CpG 19, suggesting that methylation levels in this area might be more influential in NR3C1 regulation and impact performance in cognitive tasks. For exon 1H, the areas most widely associated with cognition are in CpG 15_16 and between CpG 37 and CpG 41, while for exon 1D, all significant associations were found between CpG 15 and CpG 18. None of the NR3C1 CpG sites significantly associated with cognition in our sample were correlated to FKBP5 methylation levels, ruling out this plausible confounding factor. These results suggest that methylation levels at these areas have a higher influence on NR3C1 activity and its regulated phenotypes, such as cognition, and should be the focus of interest in future studies to confirm this relationship.

Despite previous evidence suggesting an influence of methylation levels of NR3C1 on cognitive performance in other mental health conditions, such as psychosis, where higher methylation at exon 1F has been associated with worse performance of attention and immediate memory as well as lower levels of general functioning,42 as far as we know, this study is the first one ever conducted to provide evidence of such a relationship in a sample including MDD patients. Our results also reinforce the findings of former studies that demonstrate an association between the level of NR3C1 methylation and volumetric differences in certain subfields of the hippocampus.43 Hypermethylation at exon 1F has been reported to occur in MDD associated with stressful life experiences and increased activity of the HPA axis and has also been described to mediate psychopathological expression of serious mental disorders through its influence on the activity of the HPA axis.44 Considering the specific sites associated with cognition in our sample, exon 1F CpG 17_18 site has been seen to be differentially methylated across groups in a study including first episode psychosis, schizophrenia and healthy controls.42 Interestingly, both CpG sites at exon 1F associated with cognition in our sample (CpG 17_18 and CpG 22_23_24_25), have been shown to be putative transcription factor NGFI-A binding boxes45,46 which might be the mechanism underlying the relevance of methylation levels at these specific sites. This mechanism would also explain the relationship between methylation levels at this region and cognitive performance, showing a higher influence on executive functioning; however, future studies are necessary to elucidate this pathway.

From the stratified analysis by the diagnostic group, we observe that significant associations between methylation values and cognition appear slightly more frequently in the MDD vs the HC group, reflecting a plausibly stronger relationship in these patients. This effect was accounted for in all analyses by including the depression symptoms severity (HDRS test scores) as a covariate.

We also aimed to explore the presence of interactions between genetic and epigenetic variations of NR3C1 and a history of child maltreatment on its influence on cognition. Despite previously reported evidence showing that epigenetic regulation of HPA axis genes is highly sensitive to stressful life experiences,47,48 we did not find any significant interactions in our sample. These negative results are probably due to our sample size being underpowered to perform interaction analyses; we carried out these analyses with an exploratory approach due to existing previous evidence suggesting the existence of these interactions. Future studies with larger sample sizes might be able to elucidate the extent to which stressful life experiences influence the association between NR3C1 variations and cognition. The negative results in the mediation analysis suggest that the influence of NR3C1 SNPs on cognition in the presence of early adverse events might be mediated through other mechanisms rather than through differential epigenetic regulation at the studied promoter regions.

The main strength of our study is the partial replication of previous studies reflecting a significant influence of NR3C1 SNPs on cognition in MDD patients, however, several limitations of the present study must be mentioned. First, the exploratory design of our study implies that results must be interpreted with caution and require future confirmatory studies in independent larger samples. Second, the small sample size of our study might have reduced the statistical power to detect small effect sizes. This is especially relevant for the interaction and mediation analysis since this kind of analyses require larger sample sizes and our lack of significant results in this section should be considered cautiously in this context. In the same line, individual results from the stratified analysis by diagnostic group are hard to interpret and might be unreliable given the limited size of the groups and the number of tests performed. Third, both our small sample size for a genetic association study as well as our sample characteristics, which was recruited from a tertiary source, limit the generalizability of our results which might be limited to specific contexts or populations. An especially relevant factor to consider is the relatively advanced age of the MDD group in our sample. This factor warrants careful consideration, as the associations observed between methylation and cognition in this study may not be replicable in samples of different age groups. Fourth, clinical variables such as childhood trauma were retrospectively self-reported and could be influenced by recall bias and a depressive state. Fifth, NR3C1 methylation levels were assessed in peripheral blood cells. This methodology might influence methylation values due to differences in blood cell type composition between HC and MDD patients, however differences in methylation levels between diagnostic groups was not the focus of this study. Also, methylation levels from blood cells might differ from the levels of methylation in brain tissue; even so, a high correlation between peripheral and brain tissue methylation has been shown in former studies, especially when examining CpG-enriched promoter regions.49 Sixth, we used the SEQUENOM MassArray platform for DNA methylation, a widely used and a well-established and validated method for quantitative DNA methylation analysis, however this tool provides methylations values for groups of CpG sites rather than individual specific sites, which might influence the precision of our results.

ConclusionsCognitive deficits are one of the most disabling and treatment-resistant symptomatic domains in patients with MDD. The current study sheds light upon the relationship between NR3C1 and cognition in patients with MDD. Our results show further evidence of an association between NR3C1 SNPs and specific cognitive variables in patients with MDD and show an involvement of NR3C1 regulation through promoter methylation in cognition, with a higher relationship to executive functioning tasks in our sample. The results are consistent with pre-existing evidence and might serve to build sufficient knowledge for, in the near future, provide more reliable diagnostic strategies and establish new therapeutic targets for the treatment of MDD.

FundingThis study was supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI10/01753, PI15/00662 and PI19/01040), the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) “A way to build Europe”, CIBERSAM, and the Catalan Agency for the Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR, 2017 SGR 1247). VS received an Intensification of the Research Activity Grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (INT21/00055) during 2022. We also thank CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support. Samples were processed following standard operating procedures at the Biobank HUB-ICO-IDIBELL, integrated in the Spanish Biobank Network and funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PT17/0015/0024 and PT20/00171) and by Xarxa Bancs de Tumors de Catalunya sponsored by Pla Director d’Oncologia de Catalunya (XBTC). Funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or drafting of the manuscript. The genotyping service was conducted at CEGEN-PRB2-ISCIII and supported by grants PT13/0001 and ISCIII-SGEFI/FEDER.

Declaration of competing interestNone declared.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to all study participants, as well as to the staff of the Department of Psychiatry at Bellvitge University Hospital who helped to recruit the sample for this study. We would also like to thank Anna Ferrer and Maria Badia from the Pharmacy Department at Bellvitge University Hospital for providing the 0.25mg dexamethasone capsules, the staff of Biopsychology at the Department of Psychology of the Technische Universität Dresden for analysing salivary cortisol samples, and the technicians from the Biobanc IISPV of Reus and Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG).