The Werther, Copycat or contagion effect of suicidal behaviour is a complex phenomenon that can arise due to exposure to media stories in which identifiable people take their lives. On the contrary, the Papageno effect prevents people from suicide by promoting positives examples of suicidal crisis management. Impact of both effects has been widely studied in different types of situations, but its existence in social media is a source of much debate.

MethodsA systematic search following the PRISMA guidelines of PubMed, Scopus, Embase, PsycInfo, Web of Science and the references of prior reviews yielded 25 eligible studies.

ResultsMost of the studies found were observational, with very different methodologies and generally with low risk of bias. In these, the results suggest the existence of the Werther effect in response to social media stories about suicide. This is mediated by multiple factors, including the characteristic of the users, the type of interaction and the content of the publications. At the same time, the Papageno effect is also described. Evidence found by type of social media and future implications are discussed.

ConclusionSuicidal content on social media can be both contagious and protective. It is confirmed that the Werther and Papageno effects may occur in response to social media, so they could be an interesting target for preventive interventions.

Approximately one person dies by suicide every 40s, resulting in over 700,000 deaths worldwide each year.1 Suicide in today's world is a phenomenon of great concern in both the healthcare and social realms, permeating nearly all aspects of our reality. However, the causality of this phenomenon continues to present multiple uncertainties.2

Over the past years, various theories have been developed to gain a better understanding of this interplay of factors. Currently, theories based on diathesis-stress models hold particular relevance, positing that on top of biological and genetic predisposition, life stressors trigger suicidal behaviour.3 Other hypotheses take a cognitive-behavioural approach and form the basis for many treatments.4 In recent years, there has been an emphasis on distinguishing between factors related to suicidal ideation and those relevant to the transition to suicidal behaviour. The interpersonal theory of suicide5 proposes that suicidal ideation results from the overlap of thwarted belongingness (isolation) and perceived burdensomeness. This theory introduces a third element, acquired capability, which is the reduced physical pain experienced through repeated painful behaviours, diminishing the fear of death and increasing the risk of lethal action. In the same vein, a few years later, the integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour was published, which updates and complexifies the explanatory models of suicidal behaviour. This model propose that defeat and entrapment drive the emergence of suicidal ideation and that a group of factors, termed volitional moderators (access to the means of suicide, media exposure to suicidal behaviour, impulsivity, etc.), govern the transition from suicidal ideation to suicidal behaviour.6 Another significant area of suicide study involves individual risk factors for suicide, with limited consistent evidence of direct causality for any of them by itself.7 Some are inherent to the individual, while others relate to environmental influences. There are personality differences that increase the likelihood of suicidal ideation or behaviour,8 such as impulsivity, high self-criticism, neurosis, or introversion, among others.

Furthermore, adverse social factors are also a focal point of study due to their relevance. Suicidal behaviours in acquaintances, as well as representations in various media, can have a negative impact. This contagion effect is known as the “Werther effect” or “Copycat” and can be defined as “the imitative effect that arises from social learning, in which a vulnerable person identifies with another person who has died by suicide and emulates their behavior”.9 There is evidence that the media must be cautious in how they report on suicides, as individuals with greater vulnerability may be at risk of imitation. This risk increases if the person who died by suicide had a high social status and/or was well-known, as well as if the individual identifies with the person who engaged in suicidal behaviour.10 At the same time, there has been described a protective effect when the mass media present stories of non-suicide alternatives to crises, the so-called Papageno effect.11 In this both processes, social learning is described in the literature as one of the most significant underlying mechanisms. The establishment of a set of behaviours and responses to stress as socially accepted and promoted, encourages vulnerable populations, such as adolescents and people with mental health problems, to learn and adapt suicide as an increasingly frequent problem.12

However, despite the documented phenomenon in traditional media (press, TV, etc.),13 the existing literature on the Werther effect in response to social media is limited. Regarding the most recent evidence found on social contagion and suicide, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted, on suicide contagion and on suicide prevention. The first analyzes data from three databases of studies published between 2011 and 2015 among young populations, concluding that social contagion also occurs in response to social media.14 The authors detail that online behaviour can be both harmful (normalization, triggering, competition, contagion) and beneficial (support in crisis situations, reducing social isolation, therapy, outreach). Similarly, in the prevention reviews, it is concluded that social media can allow users to intervene after an expression of suicidal ideation online and provide an anonymous, accessible, and non-judgmental forum for sharing experiences.15,16 Challenges include difficulties in controlling user behaviour, accurately assessing risks, privacy and confidentiality issues, and the potential for contagion. However, no systematic review has been found that describes the types of studies used to analyze this phenomenon or their limitations, distinguishes by the type of social media, or includes a broader time range.

Given the widespread use of social media as a form of interaction and socialization in contemporary society17 studying the phenomenon of suicide social contagion within them is of great interest. Additionally, the published evidence on the potential contagion effect in social media is scarce. Therefore, this systematic review aims to analyze, as its general objective, whether the “Werther” or social contagion phenomenon occurs in response to social media. To achieve this, it seeks to specifically examine the characteristics of studies analyzing this phenomenon, the biases and quality of such studies, the descriptions of how the Werther effect manifests in response to social media, differences across social media platforms, and differences related to whether the suicide victim is a celebrity or not.

MethodsThis systematic review was first conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.18,19 The protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database with registration number 278931. Since this systematic review is not a review of clinical trials but mainly observational studies, the E-COSMOS recommendations were reviewed and followed, which is a guide for conducting observational methodology studies (Conducting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Of Observational Studies of Etiology).20

For this systematic review, an electronic literature search was conducted for all articles published up to December 31, 2022. The bibliographic search was carried out in the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, Embase, PsycInfo, Web of Science, and IME. Advanced search options were used, combining terms that are synonymous with the Werther effect (such as copycat), synonyms and examples of social media, and, finally, specifiers for suicidal behaviour. Thus, the search used was: ((Werther effect) OR (copycat) OR (social imitation) OR (suicide contagion) OR (social contagion) AND ((Social media) OR (social network) OR (Instagram) OR (Twitter) OR (Facebook) OR (Reddit) OR (Tik Tok) OR (Twitch) OR (YouTube)) AND ((Suicide) OR (suicidality) OR (suicide ideation) OR (self-harm) OR (self-injury) OR (suicidal behaviour)).

As for the inclusion criteria for studies, the following were used: (1) studies that empirically investigate the impact of suicide descriptions on social media; (2) study designs included experimental, prospective and/or retrospective cohorts, case–control studies, and cross-sectional studies; (3) studies that measure as outcomes death by suicide or suicidal ideation, as well as any manifestation of suicidal behaviour, including studies on non-suicidal self-injury, as it is considered a risk factor for suicide; (4) studies written in English, French, or Spanish; (5) studies published up to December 31, 2022, in peer-reviewed digital format journals of any impact. Articles were excluded from the review if they: (1) were systematic reviews or meta-analyses; (2) focused on the impact in traditional media, such as print media, television, series, or books; (3) were written in a language other than English, French, or Spanish; (4) did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Two independent reviewers (CCP, SC) manually selected the articles. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus in meetings with the rest of the authors (JPCP, JE, EJAGI). After eliminating duplicates, articles that were clearly not relevant, book chapters, case reports, conference proceedings, abstracts, comments, editorials, journal notes, grey literature, and news sources were excluded in a first review based on the title. Articles selected by title were subsequently evaluated in a second review by the same authors, resulting in a 98.2% agreement rate between them. Through the reading of the articles, general data such as authors, country, and year of publication were extracted from each of them. Additionally, data related to methodology, such as the study design, its objective, target population, social media format, and the type of suicidal content studied and measured effect, were collected to address the first specific objective of the study. Whenever possible, information about the characteristics of the study sample and adherence to WHO suicide prevention protocols was obtained. For the calculation of exposure effects, all data related to effect size estimates provided by the authors were collected.

To assess the risk of bias and address the second specific objective, the ROBINS-I methodology20,21 was used, as it is the tool recommended by Cochrane and the COSMOS-E guide for new systematic reviews of observational studies. Furthermore, ROBINS-I allows for bias assessment in studies examining the effects of environmental exposures on population health.22 Results were presented using a component-wise approach, as per the latest recommendations, rather than using numerical scales.23 The level of evidence for individual studies was calculated according to the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Oxford guidelines for studies examining the aetiology of diseases.24

Due to the variety of research questions, methods used, populations, and outcomes studied, there was a high level of clinical and methodological heterogeneity among the studies, preventing any meaningful combination of study results through a meta-analysis. Therefore, a qualitative narrative synthesis was performed following the methodology recommended in previous literature.25 To evaluate the articles and extract a measure of the effect, the findings from each study included in the review were analyzed according to the third, fourth, and fifth specific objectives, with qualified articles assessed through thematic analysis. Additionally, to provide a concise response to the overall objective, three labels were used to define the direction of the Werther effect in response to social media: (1) association between the representation of suicide on social media and an increase in imitative acts; (2) association between the representation of suicide on social media and a decrease in imitative acts; (3) absence of a copycat/Werther effect.

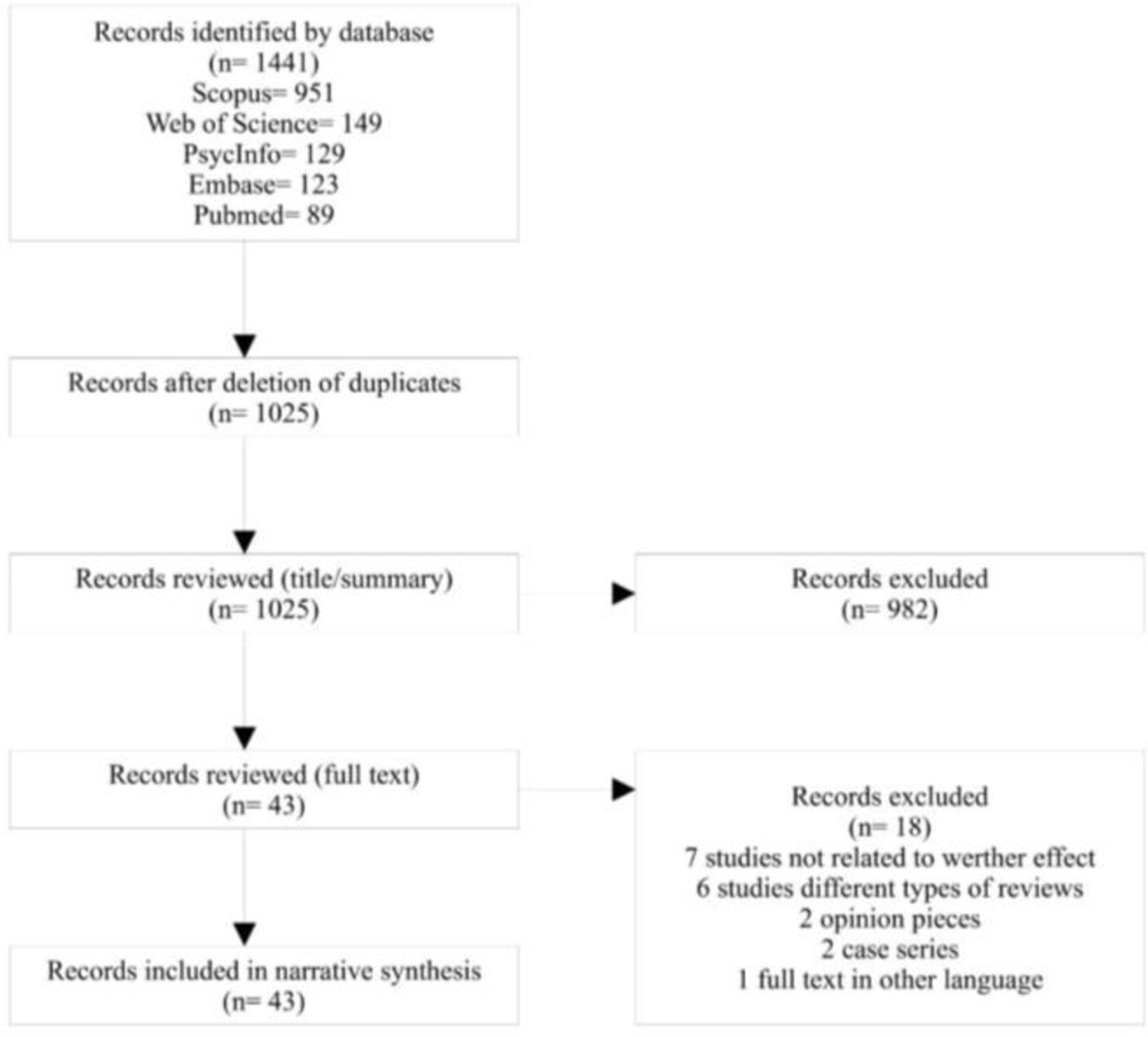

ResultsThe systematic search for articles was conducted in the aforementioned databases. Following the search methodology, a total of 1441 articles were found. In a second step, duplicates were removed (1025). After an initial selection based on the title and abstract, 982 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. After a thorough reading of the full articles, 18 articles were excluded, resulting in the final selection of 25 articles for the systematic review. The following algorithm represents the process of search, exclusion, and selection of articles (Fig. 1).

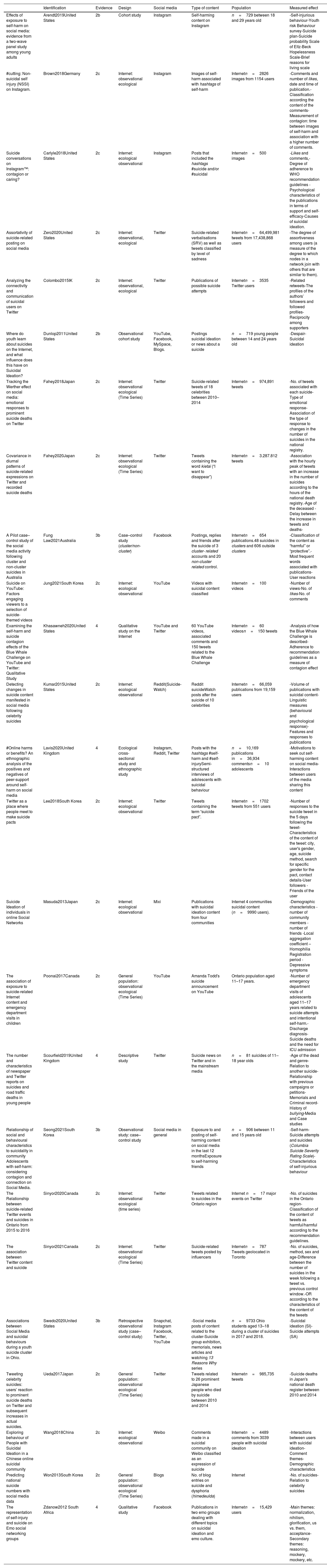

General characteristics of the studiesTable 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the included articles. Seven studies were conducted in the United States, four in South Korea, four in Japan, three studies in Canada, three studies in the United Kingdom, one study in Germany, one in Australia, one in China, and one in South Africa. Regarding the type of social media studied, nine studies focused on examining the effect on Twitter, three on Instagram, two on Facebook, two on YouTube, one assessed the effect on Reddit, one study on Mixi, and one study on Weibo. The remaining articles (n=5) analyzed the effect on more than one social media or did not specify the type of social media accessed.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies.

| Identification | Evidence | Design | Social media | Type of content | Population | Measured effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of exposure to self-harm on social media: evidence from a two-wave panel study among young adults | Arendt2019United States | 2b | Cohort study | Self-harming content on Instagram | n=729 between 18 and 29 years old | -Self-injurious behaviour-Youth risk Behaviour survey-Suicide plan-Suicide probability Scale of Eltz-Beck Hopelessness Scale-Brief reasons for living scale | |

| #cutting: Non-suicidal self injury (NSSI) on Instagram. | Brown2018Germany | 2c | Internet: observational ecological | Images of self-harm associated with hashtags of self-harm | Internetn=2826 images from 1154 users | -Comments and number of likes, date and time of publication.-Classification according the content of the comments-Measurement of contagion: time between images of self-harm and association with a higher number of comments. | |

| Suicide conversations on Instagram™: contagion or caring? | Carlyle2018United States | 2c | Internet: ecological observational | Posts that included the hashtags #suicide and/or #suicidal | Internetn=500 images | -Likes and comments,-Degree of adherence to WHO recommendation guidelines -Psychological characteristics of the publications in terms of support and self-efficacy-Causes of suicidal ideation. | |

| Assortativity of suicide-related posting on social media | Zero2020United States | 2c | Internet: observational, ecological | Suicide-related verbalisations (SRV) as well as tweets classified by level of sadness | Internetn=64,499,981 tweets from 17,438,868 users | -The degree of assortiveness among users (a measure of the degree to which nodes in a network join with others that are similar to them). | |

| Analyzing the connectivity and communication of suicidal users on Twitter | Colombo2015IK | 2c | Internet: observational, ecological | Publications of possible suicide attempts | Internetn=3535 Twitter users | -Related retweets-The profiles of the authors’ followers and followed profiles-Reciprocity among supporters | |

| Where do youth learn about suicides on the Internet, and what influence does this have on Suicidal Ideation? | Dunlop2011United States | 2b | Observational cohort study | YouTube, Facebook, MySpace, Blogs. | Postings suicidal ideation or news about a suicide | n=719 young people between 14 and 24 years old | -Despair-Suicidal ideation |

| Tracking the Werther effect on social media: emotional responses to prominent suicide deaths on Twitter | Fahey2018Japan | 2c | Internet: observational ecological (Time Series) | Suicide-related tweets of 18 celebrities between 2010–2014 | Internetn=974,891 tweets | -No. of tweets associated with each suicide-Type of emotional response-Association of the type of response to changes in the number of suicides in the national registry. | |

| Covariance in diurnal patterns of suicide-related expressions on Twitter and recorded suicide deaths | Fahey2020Japan | 2c | Internet: observational ecological (Time Series) | Tweets containing the word kietai (“I want to disappear”) | Internetn=3.287.812 tweets | -Association with the hourly peak of tweets with an increase in the number of suicides according to the hours of the national death registry.-Age of the deceased -Delay between the increase in tweets and deaths- | |

| A Pilot case–control study of the social media activity following cluster and non-cluster suicides in Australia | Fung Law2021Australia | 3b | Case–control study (cluster/non-cluster) | Postings, replies and friends after the suicide of 3 cluster- related accounts and 20 non-cluster related control. | Internetn=654 publications.48 suicides in clusters and 606 outside clusters | -Classification of the content as “harmful” or “protective”.-Most frequent words associated with publications-User reactions | |

| Suicide on YouTube: Factors engaging viewers to a selection of suicide-themed videos | Jung2021South Korea | 2c | Internet: ecological observational | YouTube | Videos with suicidal content classified | Internetn=100 videos | -Number of views-No. of likes-No. of comments |

| Examining the self-harm and suicide contagion effects of the Blue Whale Challenge on YouTube and Twitter: Qualitative Study | Khasawneh2020United States | 4 | Qualitative study on the Internet | YouTube and Twitter | 60 YouTube videos, associated comments and 150 tweets related to the Blue Whale Challenge | Internetn=60 videosn=150 tweets | -Analysis of how the Blue Whale Challenge is described-Adherence to recommendation guidelines as a measure of contagion effect |

| Detecting changes in suicide content manifested in social media following celebrity suicides | Kumar2015United States | 2c | Internet: ecological observational | Reddit(Suicide-Watch) | Reddit suicideWatch posts after the suicide of 10 celebrities | Internetn=66,059 publications from 19,159 users | -Volume of publications with suicidal content-Linguistic measures (behavioural and psychological response)-Features and responses to publications |

| #Online harms or benefits? An ethnographic analysis of the positives and negatives of peer-support around self-harm on social media | Lavis2020United Kingdom | 4 | Ecological cross-sectional study and ethnographic study | Instagram, Reddit, Twitter | Posts with the hashtags #self-harm and #self-injurySemi-structured interviews of adolescents with suicidal behaviour | n=10,169 publications in=36,934 commentsn=10 adolescents | -Motivations to seek out self-harming content on social media-Interactions between users of the media sharing this content |

| Twitter as a place where people meet to make suicide pacts | Lee2018South Korea | 2c | Internet: ecological observational | Tweets containing the term “suicide pact”. | Internetn=1702 tweets from 551 users | -Number of responses to the suicide tweet in the 5 days following the tweet-Characteristics of the content of the tweet: city, user's gender, age, suicide method, search for specific gender for the pact, contact details-User followers -Friends of the user | |

| Suicide Ideation of individuals in online Social Networks | Masuda2013Japan | 2c | Internet: ecological observational | Mixi | Publications with suicidal ideation content from four communities | Internet 4 communities suicidal content (n=9990 users). | -Demographic characteristics -number of community members -number of friends -Local aggregation coefficient – Homophilia Registration period -Depressive symptoms |

| The association of exposure to suicide-related Internet content and emergency department visits in children | Poonai2017Canada | 2c | General population: observational ecological (Time Series) | YouTube | Amanda Todd's suicide announcement on YouTube | Ontario population aged 11–17 years. | -Number of emergency department visits of adolescents aged 11–17 years related to suicide attempts and intentional self-harm.-Discharge diagnosis-Suicide deaths and the need for ICU admission |

| The number and characteristics of newspaper and Twitter reports on suicides and road traffic deaths in young people | Scourfield2019United Kingdom | 4 | Descriptive study | Suicide news on Twitter and in the mainstream media | n=81 suicides of 11–18 year olds | -Age of the dead and genre-Relation to another suicide-Relationship with previous campaigns or petitions-Memorials and Criminal record-History of bullying-Media and Case studies | |

| Relationship of social and behavioural characteristics to suicidality in community Adolescents with self-harm: considering contagion and connection on Social Media. | Seong2021South Korea | 3b | Observational study: case–control study | Social media in general | Exposure to and posting of self-harming content on social media in the last 12 monthsExposure to self-harming friends | n=906 between 11 and 15 years old | -Self-harm-Suicide attempts and suicides (Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale)-Characteristics of self-injurious behaviour |

| The Relationship between suicide-related Twitter events and suicides in Ontario from 2015 to 2016 | Sinyor2020Canada | 2c | Internet: observational ecological (time series) | Tweets related to suicides in the Ontario region | Internet n=17 major events on Twitter | -No. of suicides in the Ontario region-Classification of the content of tweets as harmful/harmful according to the recommendation guidelines. | |

| The association between Twitter content and suicide | Sinyor2021Canada | 2c | Internet: observational ecological (Time Series) | Suicide-related tweets posted by influencers | Internetn=787 Tweets geolocated in Toronto | -No. of suicides, method, sex and age-Difference between the number of suicides in the week following a tweet vs. previous control window.-OR according to the characteristics of the content of the tweets | |

| Associations between Social Media and suicidal behaviours during a youth suicide cluster in Ohio. | Swedo2020United States | 3b | Retrospective observational study (case–control study) | Snapchat, Instagram Facebook, Twitter, YouTube | -Social media posts of content related to the cluster-Suicide group exhibition, memorials, news articles and watching 13 Reasons Why series | n=9733 Ohio students aged 13–18 during a cluster of suicides in 2017 and 2018. | -Suicidal ideation (SI)-Suicide attempts (SA) |

| Tweeting celebrity suicides: users’ reaction to prominent suicide deaths on Twitter and subsequent increases in actual suicides. | Ueda2017Japan | 2c | General population: observational ecological (Time Series) | Tweets related to 26 prominent Japanese people who died by suicide between 2010 and 2014 | Internetn=985,735 tweets | -Suicide deaths in Japan's national death register between 2010 and 2014 | |

| Exploring behaviour of People with Suicidal Ideation in a Chinese online suicidal community | Wang2018China | 2c | Internet: ecological observational | Comments made in a suicidal community on Weibo classified as an expression of suicide | Internetn=4489 comments from 3039 people with suicidal ideation | -Interactions between users with suicidal ideation-Comment themes-Demographic characteristics | |

| Predicting national suicide numbers with social media data | Won2013South Korea | 2c | General population: observational ecological (Time Series) | Blogs | No. of blog entries on suicide and dysphoria (himedeulda) | Internet | -No. of suicides-Relation to celebrity suicides |

| The representation of self-injury and suicide on Emo social networking groups | Zdanow2012 South Africa | 4 | Qualitative study | Publications in two emo groups dealing with different topics on suicidal ideation and emo culture. | Internetn=15,429 users | -Main themes: normalization, nihilism, glorification, us vs. them, acceptance-Secondary themes: reasoning, mockery, mockery, etc. |

Regarding the type of study conducted, two were cohort studies, nine were ecological studies based on Internet publications, and seven were ecological studies but with a population sample. Three studies were case–control studies, and finally, four qualitative studies were also included. Among all the reviewed articles, no experimental study was found. The included articles are highly heterogeneous in nature and generally present low scientific evidence, as they are observational articles, mostly population-based, given the difficulty of conducting clinical trials in this field.

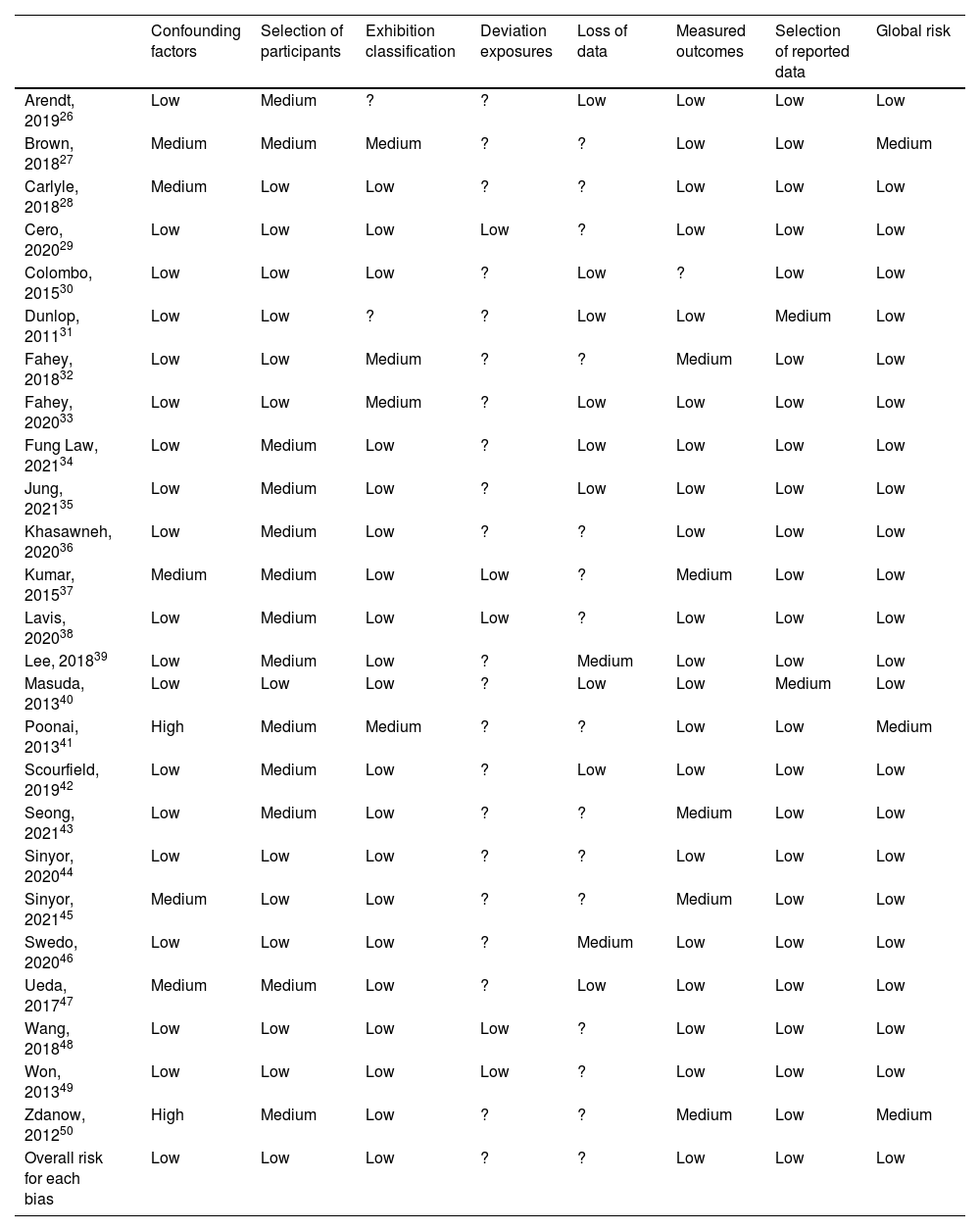

To assess the risk of bias in individual studies, the I-ROBINS tool was employed. Table 2 summarizes the measures taken by each study to mitigate bias and assess the overall risk of bias for each article, as well as for each specific type of bias. Evaluating bias is complex due to the heterogeneity of the studies, as these are not clinical trials with a control group and an intervention group. Instead, we found that while some articles examine social media posts, others base their research on social media users or the general population. Annex I contains a set of considerations regarding the methodology used to assess biases. In broad terms, it can be stated that the majority of articles had a low risk of bias.

Summary of bias risk for the included studies.

| Confounding factors | Selection of participants | Exhibition classification | Deviation exposures | Loss of data | Measured outcomes | Selection of reported data | Global risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arendt, 201926 | Low | Medium | ? | ? | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Brown, 201827 | Medium | Medium | Medium | ? | ? | Low | Low | Medium |

| Carlyle, 201828 | Medium | Low | Low | ? | ? | Low | Low | Low |

| Cero, 202029 | Low | Low | Low | Low | ? | Low | Low | Low |

| Colombo, 201530 | Low | Low | Low | ? | Low | ? | Low | Low |

| Dunlop, 201131 | Low | Low | ? | ? | Low | Low | Medium | Low |

| Fahey, 201832 | Low | Low | Medium | ? | ? | Medium | Low | Low |

| Fahey, 202033 | Low | Low | Medium | ? | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Fung Law, 202134 | Low | Medium | Low | ? | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Jung, 202135 | Low | Medium | Low | ? | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Khasawneh, 202036 | Low | Medium | Low | ? | ? | Low | Low | Low |

| Kumar, 201537 | Medium | Medium | Low | Low | ? | Medium | Low | Low |

| Lavis, 202038 | Low | Medium | Low | Low | ? | Low | Low | Low |

| Lee, 201839 | Low | Medium | Low | ? | Medium | Low | Low | Low |

| Masuda, 201340 | Low | Low | Low | ? | Low | Low | Medium | Low |

| Poonai, 201341 | High | Medium | Medium | ? | ? | Low | Low | Medium |

| Scourfield, 201942 | Low | Medium | Low | ? | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Seong, 202143 | Low | Medium | Low | ? | ? | Medium | Low | Low |

| Sinyor, 202044 | Low | Low | Low | ? | ? | Low | Low | Low |

| Sinyor, 202145 | Medium | Low | Low | ? | ? | Medium | Low | Low |

| Swedo, 202046 | Low | Low | Low | ? | Medium | Low | Low | Low |

| Ueda, 201747 | Medium | Medium | Low | ? | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Wang, 201848 | Low | Low | Low | Low | ? | Low | Low | Low |

| Won, 201349 | Low | Low | Low | Low | ? | Low | Low | Low |

| Zdanow, 201250 | High | Medium | Low | ? | ? | Medium | Low | Medium |

| Overall risk for each bias | Low | Low | Low | ? | ? | Low | Low | Low |

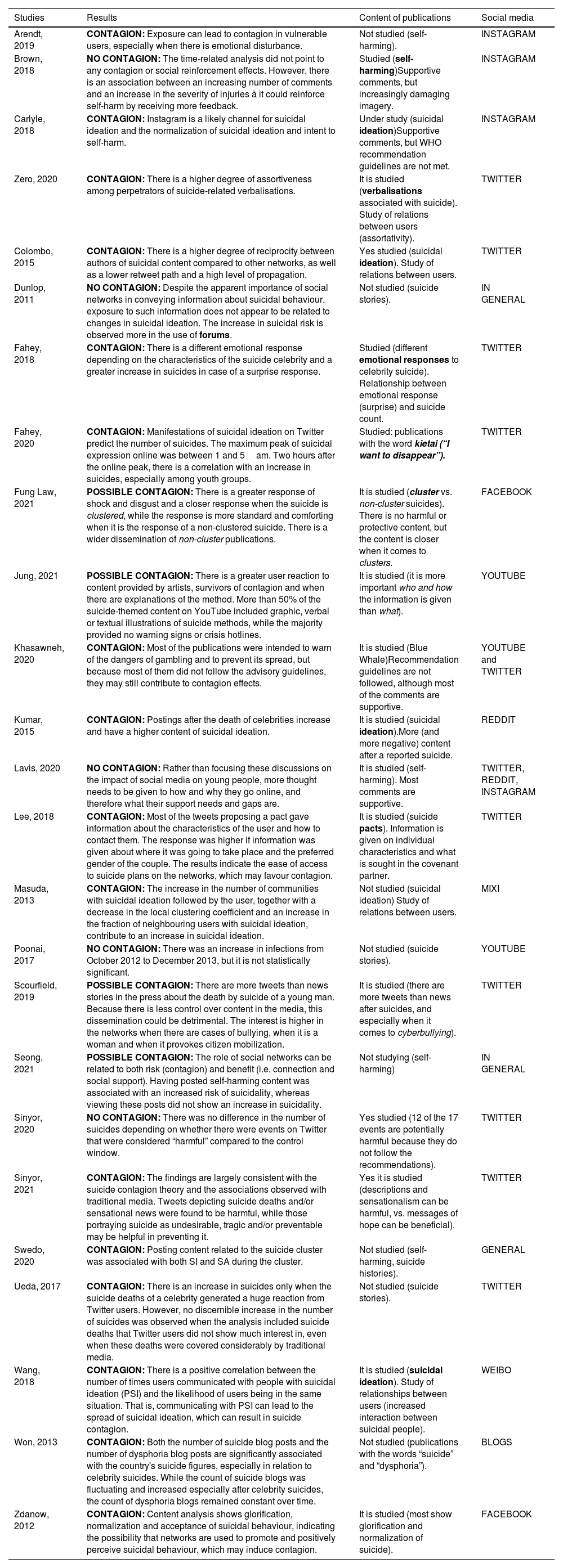

The contagion effect was measured differently in the articles. Some analyzed the Werther effect in a specific population sample by studying how suicidal ideation changes after exposure to suicidal content on social media (n=2). While one found an effect after this exposure,26 another did not find a relationship.31 These studies were conducted in the adolescent population and analyzed the use of social media in general, without going into detail about studying the content.

Another type of study used the general population of a country as a reference population. By using a country's national death registry, it was compared with other temporal series, analyzing the number and amount of posts, related or unrelated to the suicide of a famous person (n=7). In this case, these studies are also interesting because they allow the analysis of phenomena such as how suicidal ideation changes after the death of a famous person and how this is reflected on social media (measuring the volume of tweets, for example, analyzing language and emotional expressiveness in posts). Five of these studies showed a contagion effect, especially in relation to the emotional response it elicited from users32 and how sensationalism exacerbates this phenomenon.45 However, two publications of this type did not find a relationship.41,44

A different way of conducting ecological studies in this field has been through the analysis of the content of posts and/or the investigation of the relationships formed among different social media users. Nine studies of this type were found, of which eight showed a relationship between harmful content and increased suicidal ideation. It is worth noting that in this case, the direct consequences of viewing this content are not studied; instead, a higher risk is assumed. This may be because greater assortativity has been observed among users who verbalize suicidal ideation.29,30,40,48 It has also been observed that there is more negative content posted on social media after the suicide of a famous person.37 Additionally, social media have become a place where people can find partners to make suicide pacts.39 It can also be added that most of these studies that analyzed the content of posts found that the content is predominantly harmful, as it does not adhere to WHO recommendations.28

There were also three case–control studies. These studies were based on groups of teenagers as the population. The effect was studied concerning different suicide clusters that occurred in schools. Data from posts related to suicides and whether they had viewed posts related to self-harm or suicide were extracted. All three studies showed a relationship between viewing and posting this type of content and an increase in suicidal ideation.34,43,46 Furthermore, it was observed that when posts were related to suicide clusters, it increased attention and involvement with the content, which would increase suicidality.34,46

Finally, there were four more descriptive and qualitative studies, where posts in different groups were analyzed, such as emo groups,50 or the phenomenon of the Blue Whale challenge. It was observed that these groups can be genuine instigators for suicide in vulnerable individuals because, although many of the studied comments are supportive, they do not follow suicide treatment recommendations and normalize and glorify suicide.50

Regarding the factors influencing the intensity and probability of social contagion of suicide behaviour, the majority of the articles expose that what matters the most is the context, protagonist and characteristics of the exposition, as can be seen in Table 3. To summarize and organize the results of the different studies, the factors that are suitable to influence the contagion have been classified into three categories: characteristics of the user who reads the content, the social media interaction, and the protagonist who publish the content. In terms of the characteristics of the user who sees suicidal content in social media, three characteristics that enhance suicide contagion were identified. First, if the user it's suffering of a psychiatric disorder or is in a vulnerable situation including being under 18 as a vulnerable characteristic in which greater contagion33 have been found. Second, if the user is intentionally looking for this content.26 And third, if the user is actively posting content instead of only reading.43,46

Summary of conclusions of the included studies.

| Studies | Results | Content of publications | Social media |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arendt, 2019 | CONTAGION: Exposure can lead to contagion in vulnerable users, especially when there is emotional disturbance. | Not studied (self-harming). | |

| Brown, 2018 | NO CONTAGION: The time-related analysis did not point to any contagion or social reinforcement effects. However, there is an association between an increasing number of comments and an increase in the severity of injuries à it could reinforce self-harm by receiving more feedback. | Studied (self-harming)Supportive comments, but increasingly damaging imagery. | |

| Carlyle, 2018 | CONTAGION: Instagram is a likely channel for suicidal ideation and the normalization of suicidal ideation and intent to self-harm. | Under study (suicidal ideation)Supportive comments, but WHO recommendation guidelines are not met. | |

| Zero, 2020 | CONTAGION: There is a higher degree of assortiveness among perpetrators of suicide-related verbalisations. | It is studied (verbalisations associated with suicide). Study of relations between users (assortativity). | |

| Colombo, 2015 | CONTAGION: There is a higher degree of reciprocity between authors of suicidal content compared to other networks, as well as a lower retweet path and a high level of propagation. | Yes studied (suicidal ideation). Study of relations between users. | |

| Dunlop, 2011 | NO CONTAGION: Despite the apparent importance of social networks in conveying information about suicidal behaviour, exposure to such information does not appear to be related to changes in suicidal ideation. The increase in suicidal risk is observed more in the use of forums. | Not studied (suicide stories). | IN GENERAL |

| Fahey, 2018 | CONTAGION: There is a different emotional response depending on the characteristics of the suicide celebrity and a greater increase in suicides in case of a surprise response. | Studied (different emotional responses to celebrity suicide). Relationship between emotional response (surprise) and suicide count. | |

| Fahey, 2020 | CONTAGION: Manifestations of suicidal ideation on Twitter predict the number of suicides. The maximum peak of suicidal expression online was between 1 and 5am. Two hours after the online peak, there is a correlation with an increase in suicides, especially among youth groups. | Studied: publications with the word kietai (“I want to disappear”). | |

| Fung Law, 2021 | POSSIBLE CONTAGION: There is a greater response of shock and disgust and a closer response when the suicide is clustered, while the response is more standard and comforting when it is the response of a non-clustered suicide. There is a wider dissemination of non-cluster publications. | It is studied (cluster vs. non-cluster suicides). There is no harmful or protective content, but the content is closer when it comes to clusters. | |

| Jung, 2021 | POSSIBLE CONTAGION: There is a greater user reaction to content provided by artists, survivors of contagion and when there are explanations of the method. More than 50% of the suicide-themed content on YouTube included graphic, verbal or textual illustrations of suicide methods, while the majority provided no warning signs or crisis hotlines. | It is studied (it is more important who and how the information is given than what). | YOUTUBE |

| Khasawneh, 2020 | CONTAGION: Most of the publications were intended to warn of the dangers of gambling and to prevent its spread, but because most of them did not follow the advisory guidelines, they may still contribute to contagion effects. | It is studied (Blue Whale)Recommendation guidelines are not followed, although most of the comments are supportive. | YOUTUBE and TWITTER |

| Kumar, 2015 | CONTAGION: Postings after the death of celebrities increase and have a higher content of suicidal ideation. | It is studied (suicidal ideation).More (and more negative) content after a reported suicide. | |

| Lavis, 2020 | NO CONTAGION: Rather than focusing these discussions on the impact of social media on young people, more thought needs to be given to how and why they go online, and therefore what their support needs and gaps are. | It is studied (self-harming). Most comments are supportive. | TWITTER, REDDIT, INSTAGRAM |

| Lee, 2018 | CONTAGION: Most of the tweets proposing a pact gave information about the characteristics of the user and how to contact them. The response was higher if information was given about where it was going to take place and the preferred gender of the couple. The results indicate the ease of access to suicide plans on the networks, which may favour contagion. | It is studied (suicide pacts). Information is given on individual characteristics and what is sought in the covenant partner. | |

| Masuda, 2013 | CONTAGION: The increase in the number of communities with suicidal ideation followed by the user, together with a decrease in the local clustering coefficient and an increase in the fraction of neighbouring users with suicidal ideation, contribute to an increase in suicidal ideation. | Not studied (suicidal ideation) Study of relations between users. | MIXI |

| Poonai, 2017 | NO CONTAGION: There was an increase in infections from October 2012 to December 2013, but it is not statistically significant. | Not studied (suicide stories). | YOUTUBE |

| Scourfield, 2019 | POSSIBLE CONTAGION: There are more tweets than news stories in the press about the death by suicide of a young man. Because there is less control over content in the media, this dissemination could be detrimental. The interest is higher in the networks when there are cases of bullying, when it is a woman and when it provokes citizen mobilization. | It is studied (there are more tweets than news after suicides, and especially when it comes to cyberbullying). | |

| Seong, 2021 | POSSIBLE CONTAGION: The role of social networks can be related to both risk (contagion) and benefit (i.e. connection and social support). Having posted self-harming content was associated with an increased risk of suicidality, whereas viewing these posts did not show an increase in suicidality. | Not studying (self-harming) | IN GENERAL |

| Sinyor, 2020 | NO CONTAGION: There was no difference in the number of suicides depending on whether there were events on Twitter that were considered “harmful” compared to the control window. | Yes studied (12 of the 17 events are potentially harmful because they do not follow the recommendations). | |

| Sinyor, 2021 | CONTAGION: The findings are largely consistent with the suicide contagion theory and the associations observed with traditional media. Tweets depicting suicide deaths and/or sensational news were found to be harmful, while those portraying suicide as undesirable, tragic and/or preventable may be helpful in preventing it. | Yes it is studied (descriptions and sensationalism can be harmful, vs. messages of hope can be beneficial). | |

| Swedo, 2020 | CONTAGION: Posting content related to the suicide cluster was associated with both SI and SA during the cluster. | Not studied (self-harming, suicide histories). | GENERAL |

| Ueda, 2017 | CONTAGION: There is an increase in suicides only when the suicide deaths of a celebrity generated a huge reaction from Twitter users. However, no discernible increase in the number of suicides was observed when the analysis included suicide deaths that Twitter users did not show much interest in, even when these deaths were covered considerably by traditional media. | Not studied (suicide stories). | |

| Wang, 2018 | CONTAGION: There is a positive correlation between the number of times users communicated with people with suicidal ideation (PSI) and the likelihood of users being in the same situation. That is, communicating with PSI can lead to the spread of suicidal ideation, which can result in suicide contagion. | It is studied (suicidal ideation). Study of relationships between users (increased interaction between suicidal people). | |

| Won, 2013 | CONTAGION: Both the number of suicide blog posts and the number of dysphoria blog posts are significantly associated with the country's suicide figures, especially in relation to celebrity suicides. While the count of suicide blogs was fluctuating and increased especially after celebrity suicides, the count of dysphoria blogs remained constant over time. | Not studied (publications with the words “suicide” and “dysphoria”). | BLOGS |

| Zdanow, 2012 | CONTAGION: Content analysis shows glorification, normalization and acceptance of suicidal behaviour, indicating the possibility that networks are used to promote and positively perceive suicidal behaviour, which may induce contagion. | It is studied (most show glorification and normalization of suicide). |

Regarding the characteristics of the interaction, 5 consistent conclusions in the literature have been observed. A higher number of publications49,50 and in a more visual format (images or videos), contagion is more likely to occur. Furthermore, the content of the publication, if it's part of a suicide pact or a challenge,36 or shows morbid content,45 suicide behaviour is also more likely to occur. The importance of the content of the interaction was also described. If the social media users encourages suicidal behaviour, contagion it is more likely to happen, and conversely, if the response is supportive and hopeful, it is a factor encouraging recovery.36,38 In the last group, if the person who post suicidal related content is famous or the user is very identified with the poster,30 the contagion is also more probable.

DiscussionThis review aims to update the results of a previous review on the relationship between internet use and self-harming and suicidal behaviours,14 a topic with limited published literature despite its current importance. Our results predominantly suggest that social media are acting nowadays as a source of suicidal contagion, at the same time that there is also evidence that they can serve as a protective agent. Several factors may explain this phenomenon actually occurs in response to social media. This media has replaced traditional newspapers, where this effect is already established. However, these platforms have a faster dissemination power and can connect millions of users simultaneously.30,45 Additionally, they are more accessible and have fewer restrictions, often not adhering to suicide treatment guidelines.26,27,31,36 Furthermore, social media allows users to respond to various posts and interact with other users, which encourages a feedback loop of these ideas.39 Although many comments on suicidal posts are supportive, even these can increase suicidal ideation.27 Moreover, the anonymity provided by these media facilitates greater self-expression of a highly stigmatized issue, such as mental illnesses.37,38,47

Beyond this conclusion, the complexity of the dissemination of suicidal behaviour in social media is higher than expected. In this sense, the majority of the articles conclude that what matters the most is the context and characteristics of the exposition. This conclusion is consistent with the ones of previous related reviews.14–16 However, in this review this conclusion is developed in greater depth. A gradient in which the greater the vulnerability of the person receiving the content, the greater the intensity of the social media interaction, and the greater the identification with the person posting suicidal content, the more likely it is that suicidal behaviour will be imitated. This is also consistent with the most recent published studies on suicide and social learning.51 Social learning, identification with significant others, and the normalization of specific norms play are described as the main experiences influencing suicide conduct in these context. Therefore, responding to two of the research objectives, although there are no studies as such that compare social media between them, we have observed that different characteristics of the social media have a determining influence on whether or not suicidal behaviour is contagious. Likewise, although some studies do not support the hypothesis that celebrity suicide is a risk factor for contagion, we found more literature in favour of the fact that this phenomenon does occur in response to social media content.

Lastly, it is described as fundamental in the literature, the potential benefits for suicide behaviour in social media, as they facilitate the creation of new connections and the search for help and places to share concerns. While many studies have observed that the content does not adhere to recommended guidelines, most comments are supportive.27,28 As depicted previously, when the response of the users community is positive and hopeful, the contagion does not occur, and a protection effects appears.36,38 This conclusion of our study is also particularly innovative and encouraging, as the previous literature14–16 develops to a greater extent the contagion effect and not so much the possible protective effect of social networks and supportive communities.

LimitationsOne of the most significant limitations encountered in this review is the heterogeneity of the articles, with differences in the social media studied, the content examined, as well as the samples and measures used to establish contagion. Additionally, different designs are employed, which can complicate comparisons and the generalization of results.

Another limitation is the difficulty in establishing causality since it is not possible to discern the motivations behind each post. Most articles use algorithms to analyze content, but there are limitations in determining if there is genuinely suicidal ideation. Lastly, there are no articles that include newer social media like TikTok, and other influential platforms like Facebook have been underexplored.

ImplicationsDue to the heterogeneity in methodology, it is essential to create a theoretical framework for studying the Werther effect in response to social media that allows for comparisons and generalization of results. To have representative publications, algorithms for content analysis should be improved, considering other characteristics that may explain contagion and suicide risk.30,37 Future studies can enhance research by clarifying the context of social media exposure, extending the follow-up periods, distinguishing between intentional and unintentional exposure, and delving into psychological characteristics.46

It is also interesting to explore the potential benefits of social media to maximize their potential fully. There has been limited representation on these platforms by health-related institutions, which should consider interacting with users to create references that showcase stories of hope.28 Moreover, recommended guidelines for addressing the issue safely should be applied and the effectiveness of this measure studied,32,46 along with educating about safe ways to discuss suicide.36 It is also important to identify vulnerable individuals and improve algorithms that detect content before it is posted, recommending the avoidance or removal of potentially harmful posts.36 Finally, offering offline help resources would also be interesting.

ConclusionsDue to the importance of social media in our lives, their relationship with self-harming behaviours is a hot topic in current research. Overall, the results of this review support the existence of suicide contagion in response to social media suicidal content, as they can normalize self-harm and suicide behaviour. Most articles report an increase in suicidal ideation related to the content of posts on these new platforms, as well as the importance of images and user connectivity in facilitating contagion. Additionally, the Werther effect has also been demonstrated on social media following the death of a celebrity, with an increase in the number of posts related to suicide, which has been linked to a rise in the number of suicides. Three main group of factors that facilitate the suicide contagion have been described: characteristics of the user who reads the content, the social media interaction, and the protagonist who publish the content

However, it is worth noting that beneficial effects have also been observed when alternatives to suicide are depicted to manage mental health crisis, which, if optimized, could transform these platforms into agents of change and protection, as users can find support and a place to share their concerns. Considering the significance of these platforms, especially among young people, it would be interesting for health-related institutions to increase their presence on social media and be aware of the risks associated with misuse, focusing efforts on maximizing the potential benefits they offer.

FundingThe present study was not supported by any source of funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availabilityThe database can be obtained upon reasonable request from the authors.

- •

Confounding bias has been analyzed based on the presence of a control group and whether variables that can influence suicide, such as gender, age, etc., have been controlled for. In time-series studies, we have examined whether posts made in the weeks following the suicide of a famous person are compared with the volume of posts made at times when there was no suicide of a relevant public figure.

- •

Participant selection bias sometimes refers to the selection of posts on social media. In this case, we have observed whether this selection was representative and whether randomization methods were used.

- •

Exposure classification bias takes into account whether there was blinding and randomization, as well as whether reliability was measured among classifiers when studies classified posts according to their content.

- •

Deviation from planned exposures has been analyzed based on personnel blinding (blinding of participants is not applicable in these studies).

- •

Possible bias due to missing data has been analyzed in three ways: if there is significant data loss, if this loss is somehow compensated, and finally, if the posts are from active users on social media.