Although psychotic disorders are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, the diagnostic trajectories and mortality risks across the spectrum of these disorders remain poorly understood. This study aimed to characterize diagnostic pathways and compare mortality outcomes across psychotic disorders in Catalonia.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records of 357,007 adults accessing mental health services in Catalonia from 2015 through 2019. Diagnostic categories included schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, other non-organic psychoses, unipolar psychotic depression, and other mental health diagnoses. Cox proportional hazards models assessed mortality risk, adjusting for sociodemographic factors and comorbidities.

ResultsAbout one-third of the sample received their first psychotic disorder diagnosis in specialized care. All psychotic disorders showed elevated mortality risk vs other mental health conditions. Schizophrenia had the highest risk (HR, 2.63; 95%CI, 2.46–2.81, p<0.001 followed by schizoaffective (HR, 1.99; 95%CI, 1.77–2.24, p<0.001) and delusional disorders (HR, 1.92; 95%CI, 1.66–2.21, p<0.001). Low socioeconomic status (HR, 3.69; 95%CI, 3.48–3.92, p<0.001) and comorbidities (HR, 1.82 per comorbidity; 95%CI, 1.81–1.83, p<0.001) were significant predictors of mortality across diagnoses. Gradient boosting machine modeling identified comorbidities (56.07%) and diagnostic category (24.51%) as top predictors of mortality risk.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrates significantly elevated mortality risk across the spectrum of psychotic disorders in a Southern European context, with socioeconomic factors and medical comorbidities emerging as critical determinants. These findings underscore the need for integrated care approaches addressing both mental and physical health needs in psychotic disorders.

Psychotic disorders – including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other related conditions, are serious mental illnesses associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1–3 Historically, categorical distinctions have been made between affective and non-affective psychoses, as well as across individual diagnostic entities.4,5 These distinctions remain clinically relevant, as different psychotic disorders still require specific therapeutic approaches and pharmacological treatments.6,7

However, there is increasing recognition of overlap in symptoms, genetics, risk factors, and outcomes across psychotic disorders, challenging these traditional boundaries.8,9 In addition, diagnostic changes over time and factors influencing them are not fully understood.10 Particularly, diagnostic trajectory and long-term outcomes of psychotic disorders remain areas of ongoing interest, as they could inform early interventions.10,11

This growing understanding extends to mortality risks, with recent evidence suggesting affective and non-affective psychoses sharing elevated mortality rates vs the general population.2,12 Individuals with psychotic disorders continue to experience markedly reduced life expectancy,13,14 attributed to various factors including higher rates of suicide, accidents, and natural causes of death, particularly somatic comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease.12,15 Multiple mortality predictors seem to be common across diagnostic categories, including sociodemographic factors, comorbid physical health conditions, and lifestyle factors.16,17 However, the relative contribution of these predictors and potential distinctions in mortality patterns between affective and non-affective psychoses remain areas of active investigation.2,18 Of note, most evidence on mortality in Europe comes from Nordic countries, conducting an in-depth exploration of mortality in a Southern European population could help uncover region-specific factors that influence mortality rates.19,20

Exploring shared and differing mortality risks across different diagnoses with psychotic features could provide valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of premature mortality and inform targeted interventions.21 While these findings have led to proposals for more dimensional approaches to classification and risk assessment, the persistent differences in treatment approaches underscore the continued importance of diagnostic differentiation in clinical practice and research.

In Spain, health care is administered autonomically on a per region basis. As previously proven, the region of Catalonia, with its integrated public health care system and diverse population, offers a unique context for investigating mental disorders.22 Catalonia has a highly developed, integrated public health care system that combines primary care, specialized mental health services, and social support within a single network, improving the accessibility to mental health services. Furthermore, Catalonia has a multicultural population, with individuals from various ethnic, socioeconomic, and cultural backgrounds. This diversity reflects different genetic predispositions, environmental factors, and sociocultural experiences, all of which are known to impact the onset, manifestation, and progression of psychotic disorders.23,24 To date, no specific analysis of diagnostic trajectories and mortality outcomes across the full range of psychotic disorders has been conducted in this setting. Potential findings could provide valuable insights into the long-term course of these conditions and inform strategies to reduce premature mortality.

This study aimed to (1) characterize diagnostic pathways for psychotic disorders using population-based electronic registries in Catalonia; (2) compare mortality rates and survival outcomes across psychotic disorders and other mental health conditions; and (3) identify sociodemographic and clinical factors linked to mortality risk. By focusing on a Southern European population, this research adds valuable insights into the epidemiology and outcomes of psychotic disorders in this region, addressing a gap in the existing literature and providing findings that can inform health care strategies locally and potentially in other comparable settings.

MethodsData source and demographicsData for this study was sourced from the Data Analytics Program for Health Research and Innovation (PADRIS), managed by the Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia (AQuAS). The electronic health records (EHR) data, anonymized and de-identified, was obtained in full compliance with relevant legal, regulatory, and ethical standards. PADRIS accesses individual-level data including demographic, socioeconomic, health-related, and service utilization information from the Catalan public health care system (CatSalut). This study was approved by Hospital Clínic Ethics committee (HCB/2020/0735). As this was a retrospective analysis of de-identified data, individual patient consent was deemed unnecessary.

The initial study population included a total of 357,007 adult individuals who accessed specialized mental health services at CatSalut hospital and community health units in Catalonia from January 1st, 2015 through December 31, 2019. From this cohort, we identified individuals with diagnoses of psychotic disorders or other mental health conditions. Diagnoses were coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10). For cases with multiple diagnoses across the study period, we applied a hierarchical approach based on the last diagnosis registered and the level of specialization of the mental health service. The final diagnosis was determined in the following order of precedence (from most to least specialized): inpatient units, outpatient units, and psychiatric emergency rooms. This approach aimed to capture the most accurate and latest diagnosis for each patient.

Based on their primary diagnosis, participants were categorized into 7 diagnostic groups: psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia (F20), schizoaffective disorder (F25), bipolar disorder (F31), delusional disorder (F22), other non-organic psychoses (F28), and unipolar psychotic depression (F32.3); and other mental health diagnoses as the reference group. Organic psychoses (F06) and substance-induced psychoses (F19.15) were excluded due to their distinct etiology and clinical course. For specific analyses, psychotic disorders were further subcategorized into affective – bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, unipolar psychotic depression – and non-affective psychoses, reflecting established clinical and neurobiological distinctions in the literature.6

We extracted sociodemographic information, clinical diagnoses, and health care resource utilization from the EHR. Socioeconomic status was categorized based on the Catalan Health Service pharmaceutical copayment system, which considers income levels and employment status. The socioeconomic status categories were defined as follows: ‘Exempt’ includes individuals with very low income, receiving non-contributory pensions, or long-term unemployed; ‘Low’ includes individuals with annual income <€18,000; ‘Middle’ includes those with annual income between €18,000 and €100,000; and ‘High’ includes individuals with annual income >€100,000. Comorbidities were identified through the AQUAS-PADRIS coding system, which categorizes 21 predetermined general binary health conditions based on registered ICD-10 diagnosis codes. Mental health-related categories were excluded from our comorbidity count.

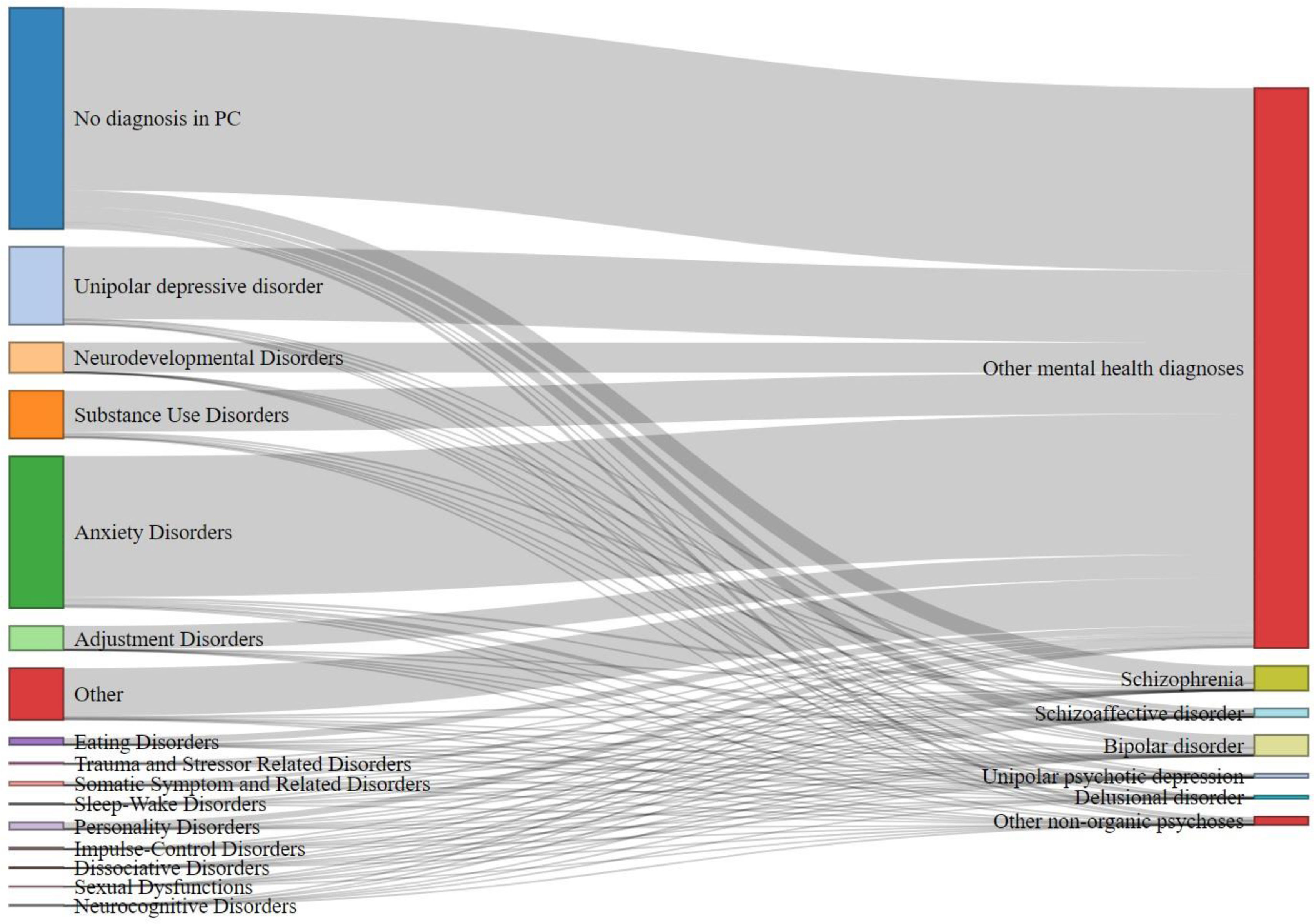

Diagnostic pathwaysThe time (in years) between the first recorded mental health diagnosis in primary care and the first recorded final mental health diagnosis was calculated. Additionally, the percentage of initial diagnoses that contributed to the final diagnostic category was determined. To visualize the diagnostic transitions, we created a Sankey flow diagram using the networkD3 package in R. This diagram illustrates the flow from initial mental health diagnoses in primary care to final diagnostic categories in specialized care. The width of each flow represents the proportion of patients transitioning across diagnostic categories, allowing for a clear visualization of the most common diagnostic pathways.

Mortality and survival analysisMortality data, including the date of death, were available from January 1st 2015, onwards, though specific causes of death were unavailable due to anonymization. The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality. Survival time was calculated from diagnosis to death or study end, whichever happened first. Covariates included sex, age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–64, 65+ years), socioeconomic status (low, middle, high, exempt), smoking status (smoker, non-smoker, ex-smoker), and number of comorbidities. Comorbidities were based on 12 chronic conditions, including diabetes, heart failure, COPD, and cancer, among others. These were coded as present (1) or absent (0), and the total number was summed for each patient using Catalan Adjusted Mortality Groups (GMA).25

Descriptive statistics characterized the study population by diagnostic group. Chi-square tests assessed differences in categorical variables, while non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for non-normally distributed continuous variables like comorbidities and years until diagnosis. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were reported. Mortality rates were estimated as crude rates per 1000 person-years for each diagnostic group, with chi-square tests used to compare rates across groups.

Survival analysis employed Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards models. Separate Kaplan–Meier curves compared survival for psychotic disorders vs other mental health disorders, specific psychotic disorder diagnoses, and affective vs non-affective psychotic disorders. Bonferroni corrections accounted for multiple comparisons: 21 pairwise comparisons for 7 diagnostic groups, 1 for binary comparisons, and 3 for 3-group analyses. The corrected significance level was calculated by dividing 0.05 by the number of comparisons.

Cox proportional hazards models estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for covariates. Proportional hazards assumptions were tested using Schoenfeld residuals. Stratified or time-dependent Cox models addressed violations in sensitivity analyses. Forest plots visualized results using ggplot2 in R.

Sensitivity analyses included stratification by comorbidities and competing risks analysis using the Fine and Gray sub distribution hazard model. Gradient boosting machine (GBM) modeling ranked the importance of predictors, using 5000 trees, a 0.01 learning rate, and an interaction depth of 3. This complemented traditional methods by emphasizing variable importance.

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.4.1. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

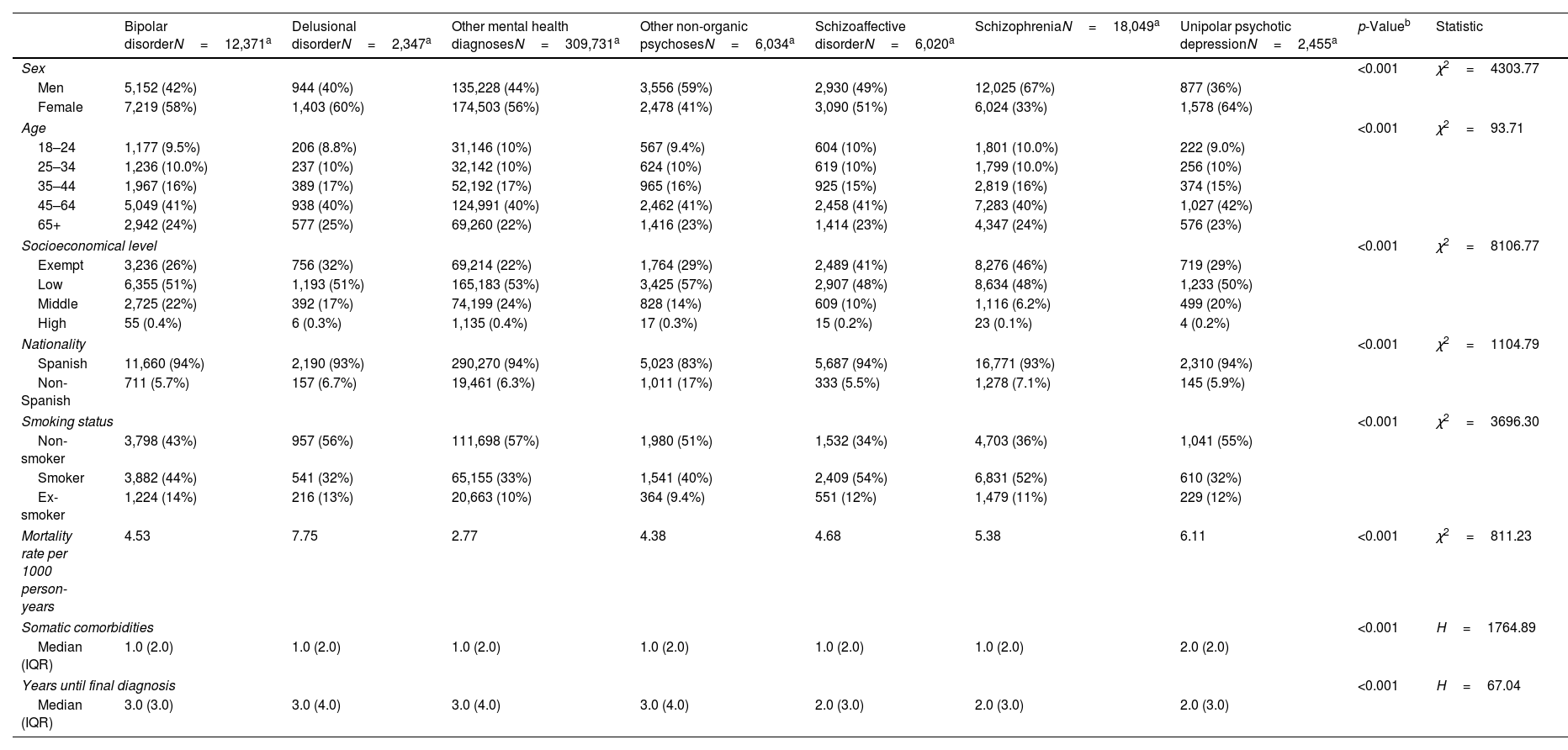

ResultsDescriptive statisticsThe study included a total of 357,007 adults accessing specialized mental health services in Catalonia from January 1st, 2015 through December 31st, 2019. The sample included bipolar disorder (3.5%), delusional disorder (0.7%), other non-organic psychoses (1.7%), schizoaffective disorder (1.7%), schizophrenia (5.1%), unipolar psychotic depression (0.7%), and other mental health diagnoses (86.8%). Significant sociodemographic and clinical differences were observed across diagnostic groups (p<0.001). The highest rate of women was in unipolar psychotic depression (64%) and lowest one in schizophrenia (33%). Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder were most prevalent in low socioeconomic groups (48%) and among current smokers (52%).

The median number of comorbidities was 1 (IQR, 2) for most groups, except unipolar psychotic depression, with a median of 2 (IQR, 2). Median time to final diagnosis ranged from 2 up to 3 years across groups, with an IQR of 3–4 years. Mortality rates also varied significantly (p<0.001), from 2.77 per 1000 person-years in other mental health diagnoses up to 7.75 in delusional disorder. Detailed sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by diagnostic group.

| Bipolar disorderN=12,371a | Delusional disorderN=2,347a | Other mental health diagnosesN=309,731a | Other non-organic psychosesN=6,034a | Schizoaffective disorderN=6,020a | SchizophreniaN=18,049a | Unipolar psychotic depressionN=2,455a | p-Valueb | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | <0.001 | χ2=4303.77 | |||||||

| Men | 5,152 (42%) | 944 (40%) | 135,228 (44%) | 3,556 (59%) | 2,930 (49%) | 12,025 (67%) | 877 (36%) | ||

| Female | 7,219 (58%) | 1,403 (60%) | 174,503 (56%) | 2,478 (41%) | 3,090 (51%) | 6,024 (33%) | 1,578 (64%) | ||

| Age | <0.001 | χ2=93.71 | |||||||

| 18–24 | 1,177 (9.5%) | 206 (8.8%) | 31,146 (10%) | 567 (9.4%) | 604 (10%) | 1,801 (10.0%) | 222 (9.0%) | ||

| 25–34 | 1,236 (10.0%) | 237 (10%) | 32,142 (10%) | 624 (10%) | 619 (10%) | 1,799 (10.0%) | 256 (10%) | ||

| 35–44 | 1,967 (16%) | 389 (17%) | 52,192 (17%) | 965 (16%) | 925 (15%) | 2,819 (16%) | 374 (15%) | ||

| 45–64 | 5,049 (41%) | 938 (40%) | 124,991 (40%) | 2,462 (41%) | 2,458 (41%) | 7,283 (40%) | 1,027 (42%) | ||

| 65+ | 2,942 (24%) | 577 (25%) | 69,260 (22%) | 1,416 (23%) | 1,414 (23%) | 4,347 (24%) | 576 (23%) | ||

| Socioeconomical level | <0.001 | χ2=8106.77 | |||||||

| Exempt | 3,236 (26%) | 756 (32%) | 69,214 (22%) | 1,764 (29%) | 2,489 (41%) | 8,276 (46%) | 719 (29%) | ||

| Low | 6,355 (51%) | 1,193 (51%) | 165,183 (53%) | 3,425 (57%) | 2,907 (48%) | 8,634 (48%) | 1,233 (50%) | ||

| Middle | 2,725 (22%) | 392 (17%) | 74,199 (24%) | 828 (14%) | 609 (10%) | 1,116 (6.2%) | 499 (20%) | ||

| High | 55 (0.4%) | 6 (0.3%) | 1,135 (0.4%) | 17 (0.3%) | 15 (0.2%) | 23 (0.1%) | 4 (0.2%) | ||

| Nationality | <0.001 | χ2=1104.79 | |||||||

| Spanish | 11,660 (94%) | 2,190 (93%) | 290,270 (94%) | 5,023 (83%) | 5,687 (94%) | 16,771 (93%) | 2,310 (94%) | ||

| Non-Spanish | 711 (5.7%) | 157 (6.7%) | 19,461 (6.3%) | 1,011 (17%) | 333 (5.5%) | 1,278 (7.1%) | 145 (5.9%) | ||

| Smoking status | <0.001 | χ2=3696.30 | |||||||

| Non-smoker | 3,798 (43%) | 957 (56%) | 111,698 (57%) | 1,980 (51%) | 1,532 (34%) | 4,703 (36%) | 1,041 (55%) | ||

| Smoker | 3,882 (44%) | 541 (32%) | 65,155 (33%) | 1,541 (40%) | 2,409 (54%) | 6,831 (52%) | 610 (32%) | ||

| Ex-smoker | 1,224 (14%) | 216 (13%) | 20,663 (10%) | 364 (9.4%) | 551 (12%) | 1,479 (11%) | 229 (12%) | ||

| Mortality rate per 1000 person-years | 4.53 | 7.75 | 2.77 | 4.38 | 4.68 | 5.38 | 6.11 | <0.001 | χ2=811.23 |

| Somatic comorbidities | <0.001 | H=1764.89 | |||||||

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (2.0) | 2.0 (2.0) | ||

| Years until final diagnosis | <0.001 | H=67.04 | |||||||

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (3.0) | 3.0 (4.0) | 3.0 (4.0) | 3.0 (4.0) | 2.0 (3.0) | 2.0 (3.0) | 2.0 (3.0) | ||

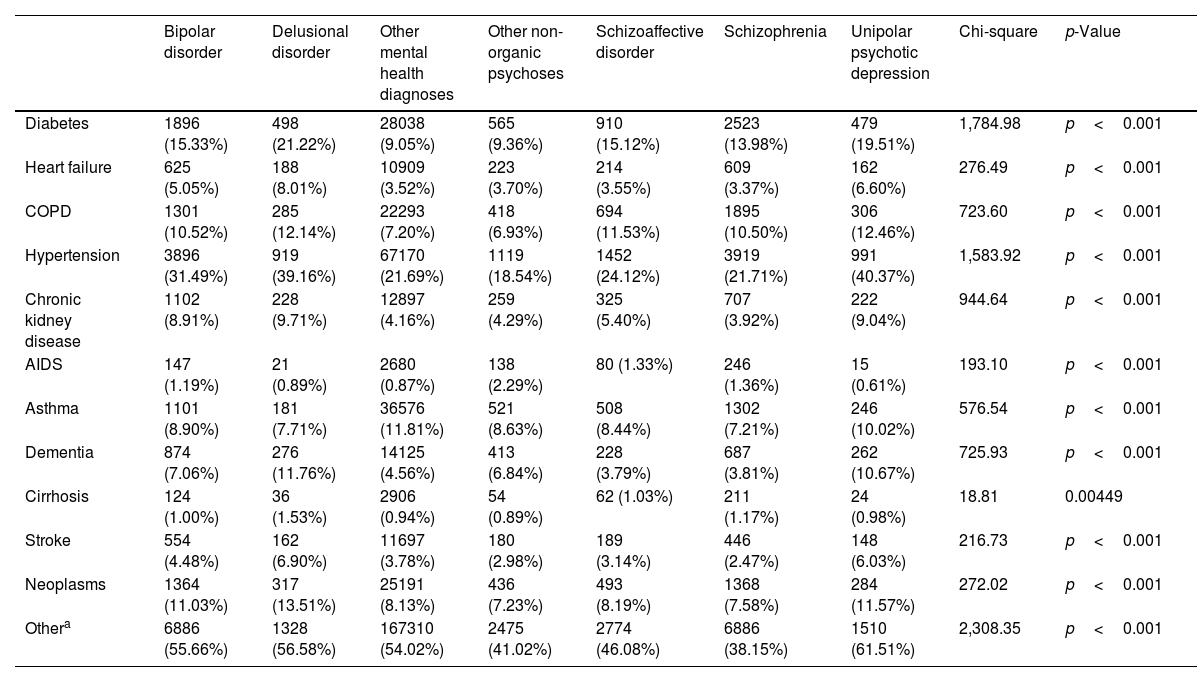

Comorbidity profiles varied significantly across diagnostic groups. Hypertension was the most prevalent comorbidity, ranging from 18.54% in other non-organic psychoses up to 40.37% in unipolar psychotic depression. Diabetes was notably common in delusional disorder (21.22%) and unipolar psychotic depression (19.51%) vs other mental health diagnoses (9.05%). Patients with affective psychoses – bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, unipolar psychotic depression – generally exhibited higher comorbidity rates vs those with non-affective psychoses. Chi-square tests confirmed significant differences (p<0.05) in the prevalence of all comorbidities across diagnostic groups (Table 2).

Comparison of somatic comorbidities across diagnostic groups.

| Bipolar disorder | Delusional disorder | Other mental health diagnoses | Other non-organic psychoses | Schizoaffective disorder | Schizophrenia | Unipolar psychotic depression | Chi-square | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 1896 (15.33%) | 498 (21.22%) | 28038 (9.05%) | 565 (9.36%) | 910 (15.12%) | 2523 (13.98%) | 479 (19.51%) | 1,784.98 | p<0.001 |

| Heart failure | 625 (5.05%) | 188 (8.01%) | 10909 (3.52%) | 223 (3.70%) | 214 (3.55%) | 609 (3.37%) | 162 (6.60%) | 276.49 | p<0.001 |

| COPD | 1301 (10.52%) | 285 (12.14%) | 22293 (7.20%) | 418 (6.93%) | 694 (11.53%) | 1895 (10.50%) | 306 (12.46%) | 723.60 | p<0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3896 (31.49%) | 919 (39.16%) | 67170 (21.69%) | 1119 (18.54%) | 1452 (24.12%) | 3919 (21.71%) | 991 (40.37%) | 1,583.92 | p<0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1102 (8.91%) | 228 (9.71%) | 12897 (4.16%) | 259 (4.29%) | 325 (5.40%) | 707 (3.92%) | 222 (9.04%) | 944.64 | p<0.001 |

| AIDS | 147 (1.19%) | 21 (0.89%) | 2680 (0.87%) | 138 (2.29%) | 80 (1.33%) | 246 (1.36%) | 15 (0.61%) | 193.10 | p<0.001 |

| Asthma | 1101 (8.90%) | 181 (7.71%) | 36576 (11.81%) | 521 (8.63%) | 508 (8.44%) | 1302 (7.21%) | 246 (10.02%) | 576.54 | p<0.001 |

| Dementia | 874 (7.06%) | 276 (11.76%) | 14125 (4.56%) | 413 (6.84%) | 228 (3.79%) | 687 (3.81%) | 262 (10.67%) | 725.93 | p<0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 124 (1.00%) | 36 (1.53%) | 2906 (0.94%) | 54 (0.89%) | 62 (1.03%) | 211 (1.17%) | 24 (0.98%) | 18.81 | 0.00449 |

| Stroke | 554 (4.48%) | 162 (6.90%) | 11697 (3.78%) | 180 (2.98%) | 189 (3.14%) | 446 (2.47%) | 148 (6.03%) | 216.73 | p<0.001 |

| Neoplasms | 1364 (11.03%) | 317 (13.51%) | 25191 (8.13%) | 436 (7.23%) | 493 (8.19%) | 1368 (7.58%) | 284 (11.57%) | 272.02 | p<0.001 |

| Othera | 6886 (55.66%) | 1328 (56.58%) | 167310 (54.02%) | 2475 (41.02%) | 2774 (46.08%) | 6886 (38.15%) | 1510 (61.51%) | 2,308.35 | p<0.001 |

This table presents the frequency (N) and percentage (%) of patients with each comorbidity across different diagnostic groups. Chi-square tests were performed to assess significant differences in comorbidity rates between groups.

Note: p-values <0.05 indicate statistically significant differences in comorbidity rates across diagnostic groups.

The median time from initial primary care (PC) diagnosis to final diagnosis varied by category. Schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and unipolar psychotic depression had the shortest median time of 2 years (IQR, 3.0), while bipolar disorder, delusional disorder, other mental health diagnoses, and other non-organic psychoses had a median of 3 years, with IQRs of 3 years for bipolar disorder and 4 for the other categories. Most patients had no prior PC diagnosis before their final diagnosis, ranging from 35.9% in unipolar psychotic depression up to 66.9% in schizophrenia, indicating many received their first mental health diagnosis in specialized care.

Anxiety disorders were the most common preceding diagnosis after no prior diagnosis, particularly in delusional disorder (21.2%) and other non-organic psychoses (20.2%). Unipolar depressive disorder was a common finding of unipolar psychotic depression (26.4%) and bipolar disorder (12.6%). Substance use disorders were present across all categories, ranging from 7.1% in unipolar psychotic depression up to 12.4% in other non-organic psychoses. Fig. 1 illustrates the transitions from initial PC diagnoses to final diagnostic categories, with detailed percentages in Supplementary Table 1.

Sankey flow diagram of initial primary care diagnoses transition to final mental health diagnoses for each diagnostic group. The Sankey flow diagram shows the transition from the sample's first mental health diagnosis registered in primary care to the final diagnostic psychotic and non-psychotic category.

Throughout the study period, a total of 11,183 deaths were recorded. Crude mortality rates per 1000 person-years (95%CI) were: bipolar disorder, 4.5 (4.1–4.9, n=572); delusional disorder, 7.8 (6.7–9.0, n=190); other non-organic psychoses, 4.4 (3.9–4.9, n=270); schizoaffective disorder, 4.7 (4.2–5.3, n=286); schizophrenia, 5.4 (5.1–5.7, n=996); unipolar psychotic depression, 6.1 (5.2–7.1, n=154); and other mental health diagnoses 2.8 (2.7–2.9, n=8715).

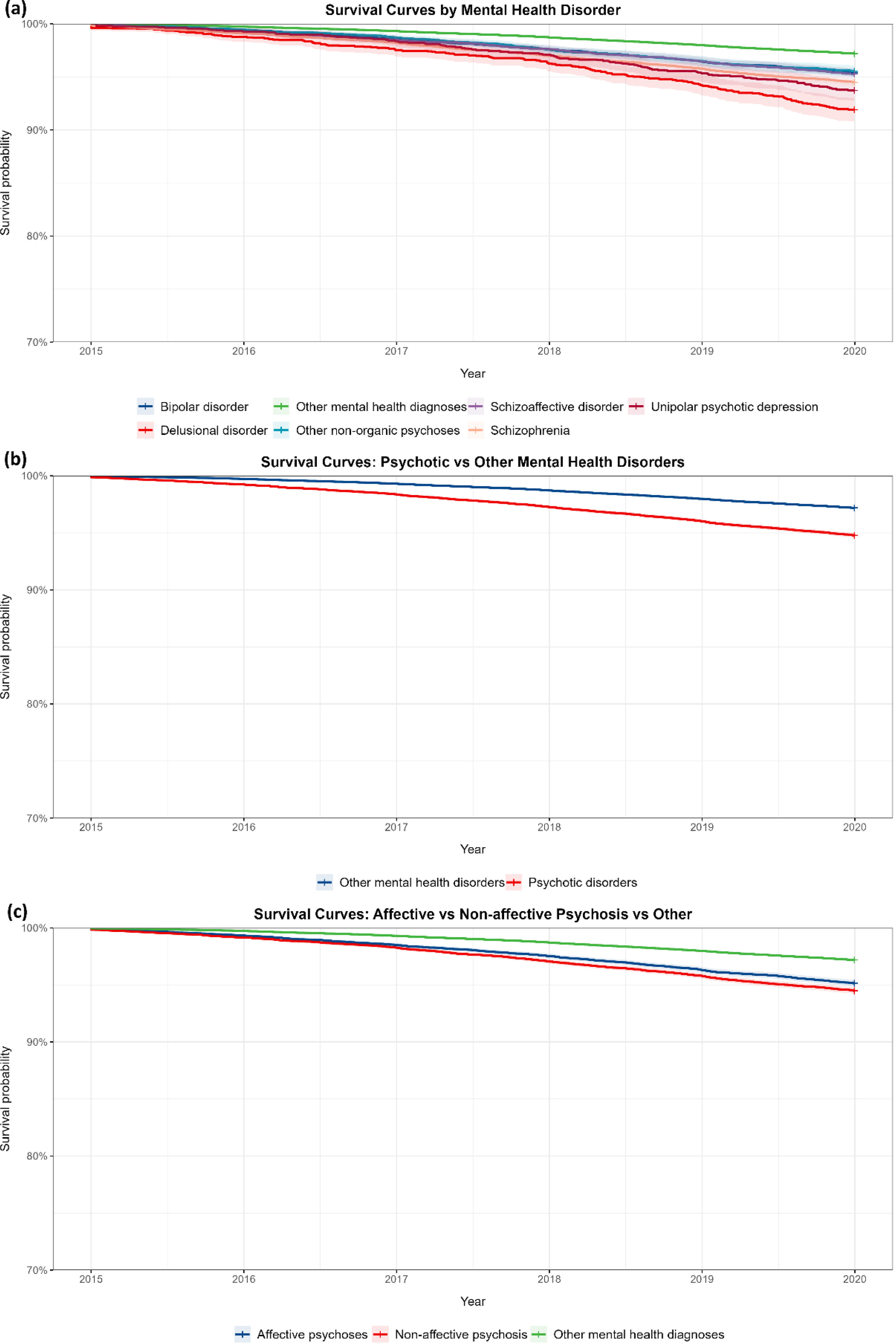

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed significant survival differences between psychotic and other mental health disorders (log-rank test χ2=813, df=2, p<0.001). All psychotic disorders demonstrated worse survival vs other mental health disorders: bipolar disorder (χ2=572), delusional disorder (χ2=190), other non-organic psychoses (χ2=270), schizoaffective disorder (χ2=286), schizophrenia (χ2=996), and unipolar psychotic depression (χ2=154) (p<0.001). Comparisons among affective psychoses, non-affective psychoses, and other mental health diagnoses also revealed significant survival differences (chi-square test=813, df=2, p<0.001). Observed vs expected deaths were affective psychoses (1012 vs 646), non-affective psychoses (1456 vs 816), and other mental health diagnoses (8715 vs 9721).

After Bonferroni correction, all analyses remained highly significant. The 7-group comparison retained significance (chi-square test=909, df=6, p<0.001 for 21 comparisons), as did binary comparisons between psychotic and other mental health disorders (chi-square test=796, df=1, p<0.001) and 3-group comparisons (chi-square test=813, df=2, p<0.001 for 3 comparisons). These results confirm the robustness of survival differences across diagnostic groups, even after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Fig. 2).

Survival curves for mental health disorders: comparative analysis of diagnostic categories (2015–2020). (a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for seven mental health diagnostic categories from 2015 to 2020. (b) Survival curves comparing psychotic disorders to other mental health disorders from 2015 to 2020. (c) Survival curves for affective psychoses, non-affective psychosis, and other mental health diagnoses from 2015 to 2020.

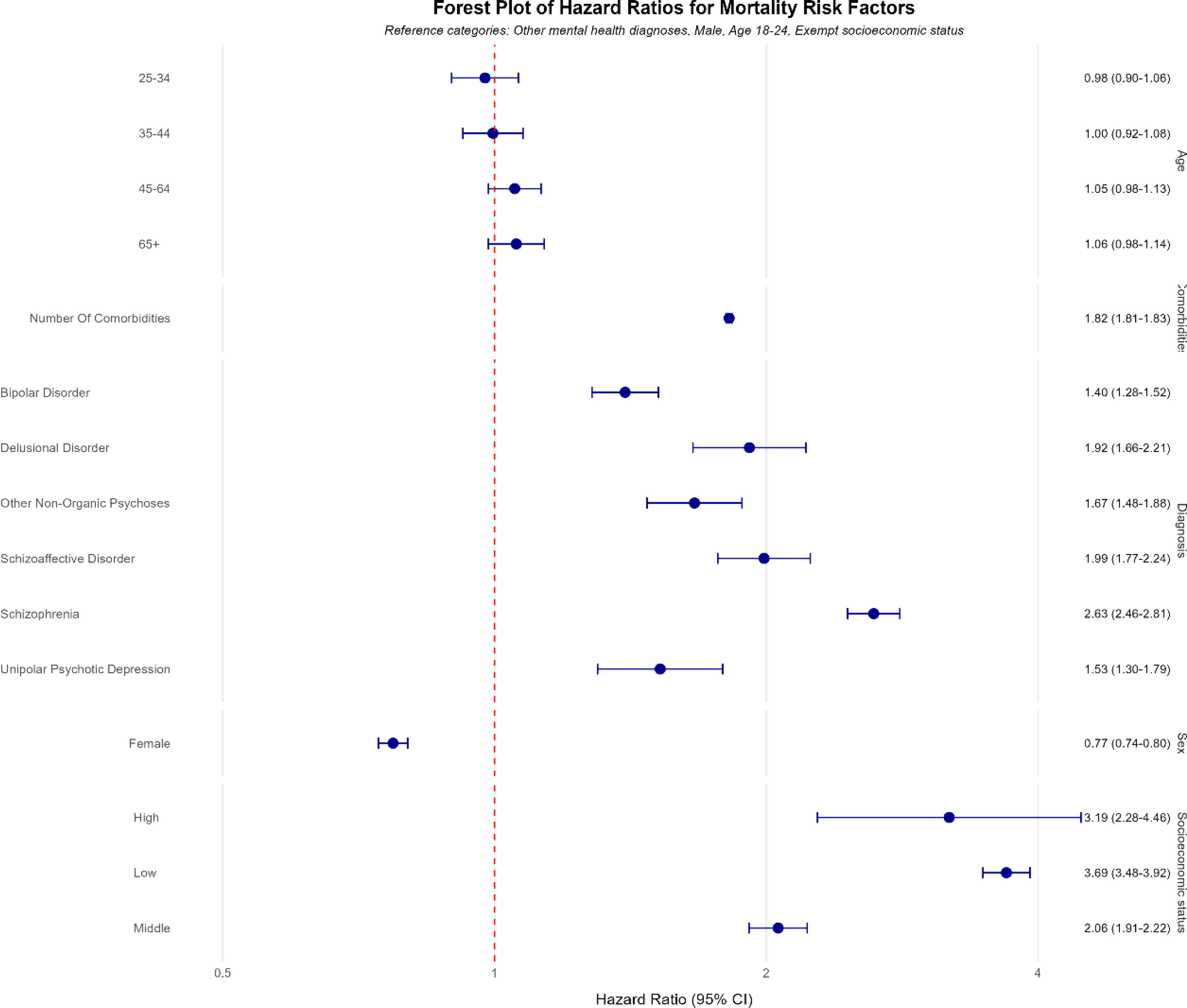

In the primary Cox proportional hazards model, all psychotic disorders were associated with higher mortality risk vs other mental health diagnoses, after adjusting for covariates. Schizophrenia posed the highest risk (HR, 2.63; 95%CI, 2.46–2.81, p<0.001), followed by delusional disorder (HR, 1.92; 95%CI, 1.66–2.21, p<0.001), schizoaffective disorder (HR, 1.99; 95%CI, 1.77–2.24, p<0.001), other non-organic psychoses (HR, 1.67; 95%CI, 1.48–1.88, p<0.001), unipolar psychotic depression (HR, 1.53; 95%CI, 1.30–1.79, p=2.06e-07), and bipolar disorder (HR, 1.40; 95%CI, 1.28–1.52, p<0.001).

Additional significant mortality predictors included male sex (HR, 1.30; 95%CI, 1.25–1.35, p<0.001), low socioeconomic status (HR, 3.69; 95%CI, 3.48–3.92, p<0.001), and number of comorbidities (HR, 1.82 per additional comorbidity; 95%CI, 1.81–1.83, p<0.001). Fig. 3 provides a forest plot illustrating these hazard ratios, highlighting schizophrenia as the highest risk and emphasizing the strong influence of socioeconomic status and comorbidities on mortality. Schoenfeld residuals testing indicated a violation of the proportional hazards assumption (chi-square test=315.29, df=15, p<0.001). To address this, sensitivity analyses employed stratified and time-dependent Cox models, ensuring robustness of the findings.

Forest plots of hazard ratio from our Cox proportional hazards model for key predictors. This figure presents the forest plots of hazard ratios derived from our Cox proportional hazards model which illustrates the hazard ratios for each individual predictor within our main variable categories: diagnosis, age, socioeconomic status, sex, and number of comorbidities.

Sensitivity analyses varying the cutoff for high comorbidity burden (1–5 comorbidities) consistently demonstrated a significant impact of comorbidities on mortality risk, with HRs for low comorbidity ranging from 0.07 to 0.11 across models. Alternative age categorizations (18–44, 45–64, 65+; and 18–34, 35–44, 45–64, 65+) and binary grouping of psychotic vs non-psychotic disorders yielded results similar to the original model, affirming its robustness.

A stratified Cox model, using diagnosis as the stratification variable produced consistent effects for other predictors and achieved a concordance index of 0.85 (SE, 0.002), indicating strong predictive accuracy. Interaction and time-dependent analyses revealed significant interactions between diagnostic groups and comorbidities (likelihood ratio test: chi-square test=222, df=6, p<0.001). A time-dependent Cox model indicated that comorbidity-related mortality risk decreased at the follow-up (interaction term coefficient: 0.0002086, p<0.001). Competing risks analysis using the Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard model confirmed increased mortality risk for psychotic disorders, even when accounting for competing causes of death.

Gradient boosting machine (GBM) modelA GBM model ranked the relative importance of predictors of mortality. The most influential predictors were the number of comorbidities (56.07%), diagnostic category (24.51%), socioeconomic status (18.59%), sex (0.59%), and age category (0.25%). This analysis underscored the dominant role of comorbidities and diagnosis in predicting mortality risk among individuals with psychotic and other mental health disorders.

DiscussionThis comprehensive study of diagnostic pathways and mortality outcomes in psychotic disorders across Catalonia offers several key insights, building on previous research. First, the transition from initial primary care diagnoses to final psychotic disorder diagnoses revealed that about one-third of patients received their first psychotic disorder diagnosis in specialized care. Second, all psychotic disorders were associated with significantly elevated mortality risks vs other mental health conditions, with schizophrenia presenting the highest risk. Third, sociodemographic factors and medical comorbidities were identified as critical predictors of mortality across all diagnostic groups.

The diagnostic transitions observed in our cohort, particularly from initial diagnoses of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders to final psychotic disorder diagnoses are consistent with previous research on prodromal symptoms in early psychosis.10 Notably, over one-third of patients received their first psychotic disorder diagnosis in specialized care rather than primary care, reflecting delayed detection of psychosis in primary care settings, consistent with findings from former studies.26 These results highlight gaps in early detection and emphasize the need for enhanced screening and referral pathways in primary care to enable earlier intervention.27,28

Our findings on excess mortality in psychotic disorders extend previous research to a Southern European context.16,21 The elevated mortality risk across all psychotic disorders, including affective psychoses, challenges traditional distinctions between affective and non-affective psychoses regarding long-term outcomes. Schizophrenia showed the highest mortality risk (HR, 2.63; 95%CI, 2.46–2.81), which is consistent with prior evidence of worse outcomes for non-affective psychoses.2 However, our HRs exceed those reported in the meta-analysis by Oakley et al., which found pooled standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) of 2.54 (95%CI, 2.35–2.75) for schizophrenia and 2.00 (95%CI, 1.70–2.34) for bipolar disorder,28 which suggests potentially greater mortality disparities in our Catalan cohort. These results build on and update recent work by Olaya et al. (2023), offering a more focused examination of mortality risks specific to psychotic disorders.22 The higher mortality risks observed may reflect the underrepresentation of Southern European populations in prior meta-analyses. Regional factors such as differences in health care access, socioeconomic conditions, comorbidities, lifestyle behaviors, and the use of pharmacological treatments such as clozapine or lithium likely contribute to these disparities.29 The higher mortality risks observed in our Catalan cohort vs to previous meta-analyses may reflect several region-specific factors. First, most former studies were conducted in Northern European countries with different health care systems, socioeconomic contexts, and lifestyle patterns. The Mediterranean context presents unique characteristics, including potential differences in diet, social support structures, health care access patterns, and treatment approaches that may influence mortality outcomes. Second, our study period (2010–2019) represents a more recent timeframe vs many former studies, potentially capturing evolving patterns in health care delivery and outcomes. Third, the structure of mental health services in Catalonia, with its particular integration between primary and specialized care might impact both the identification of cases and their subsequent management. Finally, our cohort includes the full spectrum of psychotic disorders treated in public health care settings, potentially capturing a more diverse patient population than studies focusing only on specific diagnostic categories or treatment settings.

Furthermore, although the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the excess mortality in serious mental illnesses are beyond the scope of the study, considering morbidity and mortality findings from the pre-antipsychotic era30,31 current research suggests the impact of early environmental issues in the later development of metabolic disorders and reduced life expectancy.32,33 While we could not analyze specific causes of death due to data anonymization, it is important to acknowledge that suicide likely contributes significantly to the excess mortality observed in psychotic disorders. Previous research has consistently shown elevated suicide rates in this population, with lifetime risk estimates of 5%–10% for schizophrenia and similar elevations for other psychotic disorders.15,34 The integration of suicide prevention strategies into comprehensive care approaches represents a crucial component in addressing premature mortality. Future studies with access to cause-specific mortality data in the Catalan population would provide valuable insights into the relative contribution of suicide vs natural causes, potentially revealing region-specific patterns that could inform targeted interventions.

The strong influence of socioeconomic status and medical comorbidities on mortality risk supports the need to address social determinants of health and enhance physical health care for individuals with psychotic disorders.35 Our findings highlight the complex interplay between social factors, physical health, and mortality in this vulnerable population. The gradient in mortality risk across socioeconomic strata aligns with meta-analytical data from Hjorthøj et al., who reported increased mortality in schizophrenia associated with lower socioeconomic status.16 Additionally, the high prevalence of cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities, particularly in affective psychoses, is consistent with large-scale studies such as the one conducted by Correll et al., which identified elevated cardiometabolic risks in psychotic disorders.36 This is further corroborated by reviews such as De Hert et al. and meta-analyses by Vancampfort et al., which document increased rates of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in this populations.37,38

Our findings indicating that the effect of comorbidities on mortality risk diminished over time warrant further investigation. This pattern may reflect survivorship bias, where individuals most vulnerable to comorbidity-related mortality die earlier at the follow-up, a phenomenon observed by Crump et al. in long-term studies of schizophrenia.39,40 Alternatively, it may suggest improvements in managing physical health conditions over time for survivors, which is consistent with efforts to integrate physical health care into mental health services. These findings are consistent with the framework by Firth et al. for protecting physical health in individuals with mental illness, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions addressing modifiable risk factors while mitigating the impact of socioeconomic disadvantage on health outcomes in this vulnerable group.41 A key implication for clinical care is that elevated mortality across all psychotic disorders points out that standardized physical health monitoring should be implemented regardless of specific diagnosis. Moreover, the diagnostic pathways we identified highlight opportunities for earlier detection in primary care, particularly for patients presenting with anxiety, depression, or substance use disorders. Additionally, our results support risk stratification approaches based on comorbidity burden and socioeconomic factors to identify high-risk individuals requiring more intensive intervention and care coordination.

However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. The use of administrative data may have introduced misclassification of diagnoses, a known challenge in registry-based studies.42 Anonymization procedures restricted access to specific causes of death, limiting our ability to investigate mechanisms underlying excess mortality. The relatively short study timeframe (2015–2019) may affect the robustness of survival analyses, as longer follow-up periods could reveal different mortality risk patterns over time. Additionally, while key covariates were adjusted for, unmeasured factors such as employment, marital status, or pharmacological treatments were not included, potentially influencing outcomes.43 The age groupings used may not adequately capture critical differences in mortality risk between younger and older patients with psychosis, in whom variables such as age of onset, treatment response, and accumulated health risks play significant roles. Moreover, the static age categories may overlook the dynamic nature of aging during the study period, reducing sensitivity to age as a time-varying covariate, a critical factor in mortality studies. The similar pattern of comorbidity burden across most diagnostic indicates substantial variability but generally high comorbidity burden within each group, still these findings may reflect potential underdiagnosis or underreporting of physical health conditions in psychiatric populations, a well-documented phenomenon in specialized mental health settings.44 The binary cross-sectional method of capturing comorbidities through the AQUAS-PADRIS system may not fully capture the severity or chronicity of these conditions. Despite these limitations, comorbidity burden emerged as the strongest predictor of mortality risk in our analyses, underscoring the critical importance of physical health conditions in this population. While our dataset included drug records, the complex diversity of pharmacological interventions across different psychotic disorders (including agents like clozapine and lithium with potential differential effects on mortality) made comprehensive medication analysis beyond the scope of this study. The observed temporal changes in comorbidity-associated mortality risk may partially reflect medication effects that we were unable to fully account for in our current analyses.

Despite these limitations, our study offers several strengths. Leveraging a large, comprehensive dataset encompassing all psychotic disorders recorded in public health care in Catalonia during the study period ensures a robust, population-based perspective. The use of diverse analytical methods, including Cox regressions, machine learning techniques, and sensitivity analyses, enhances the reliability of our conclusions. Notably, the gradient boosting machine model identified comorbidities and diagnostic category as the top predictors of mortality risk, reinforcing our findings and underscoring critical areas for clinical attention.

In conclusion, this study highlights the persistent mortality gap among individuals with psychotic disorders in Catalonia and provides valuable insights into the evolving nature of these diagnoses over time. The findings emphasize the urgent need for integrated care strategies to address both mental and physical health needs, as well as social determinants of health, across psychotic disorder subtypes. Future research should aim to uncover the pathways driving excess mortality in this population to enable early, targeted interventions that improve long-term outcomes. Longitudinal, multicenter studies incorporating clinical and sociodemographic data alongside biomarkers, neuroimaging, specific causes of death, and ecological socioeconomic factors are essential. Such comprehensive approaches could shed light on the mechanisms underlying mortality disparities and guide personalized treatment strategies and public health initiatives to improve survival and quality of life for individuals with psychotic disorders. In our opinion, future research should examine how specific pharmacological interventions modify mortality risk across different psychotic disorders, with particular attention to agents like clozapine and lithium that have shown protective effects in previous studies. Such analyses would benefit from detailed drug data including specific agents, dosages, duration of treatment, and adherence patterns.

Declaration of competing interestSantiago Madero has received CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from BeckleyPsytech, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Lundbeck/Otsuka, and Viatris, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Gerard Anmella has received CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from Adamed, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Lundbeck/Otsuka, Rovi, and Viatris, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Eduard Vieta has received grants and served as consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, AbbVie, Angelini, Biogen, Biohaven, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celon Pharma, Compass, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ethypharm, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Idorsia, Janssen, Lundbeck, Medincell, Novartis, Orion Corporation, Organon, Otsuka, Rovi, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and Viatris, outside the submitted work. Diego Hidalgo-Mazzei has received CME-related honoraria and served as a consultant for Abbott, Angelini, Ethypharm Digital Therapy and Janssen-Cilag. All other authors declared no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Miquel Bioque has been a consultant for, received grant/research support and honoraria from, has been on the speakers/advisory board, and has received honoraria from and/or consultancy fees from Adamed, Angelini, Casen-Recordati, Exeltis, Ferrer, Janssen, Lundbeck, Neuraxpharm, Otsuka, Pfizer, Rovi and Sanofi, as well as grants from the Spanish Ministry of Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI20/01066), Fundació La Marató de TV3 (202206-30-31) and Pons-Bartran legacy (FCRB_IPB1_2023). Silvia Amoretti has been a consultant and/or received honoraria/grants from Otsuka-Lundbeck, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Vicent Llorca-Bofí has received financial support for continuing medical education from Adamed, Advanz Pharma, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Exeltis, Janssen, Lundbeck, Neurocrine Biosciences and Rovi outside the submitted work. Norma Verdolini has received financial support for CME activities and travel expenses from the following entities (unrelated to the present work): Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka. The rest of the authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

This study has been conducted using the anonymized data from the Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia (AQuAS), within the framework of the Data Analytics Program for Health Research and Innovation (PADRIS) (https://aquas.gencat.cat/). This study has been funded by the following research grants: Ajut a la Recerca Pons Bartran 2020 – Fundació Clínic Recerca Biomèdica (project PI046549) and Strategic Projects Oriented to the Ecological Transition and the Digital Transition 2021 (TED2021-131999B-I00), Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. Fundació Clínic Recerca Biomèdica or Agencia Estatal de Investigación had no further role in the study design; in data collection, analysis, and interpretation; in the drafting of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication purposes. Santiago Madero received funding through Contractes Clínic de Recerca "Emili Letang - Josep Font" 2020, granted by Hospital Clínic de Barcelona". Ariadna Mas’ contract was funded by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR. Clàudia Valenzuela-Pascual has been supported by a Formación de Profesorado Universitario 2023 grant from the Spanish Ministry of Universities. Gerard Anmella is supported by a Juan Rodés 2023 grant (JR23/00050), a Rio Hortega 2021 grant (CM21/00017) and Acción Estratégica en Salud – Mobility (M-AES) fellowship (MV22/00058), from the Spanish Ministry of Health financed by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-financed by the Fondo Social Europeo Plus (FSE+). Gerard Anmella thanks the support granted by the Spanish Ministry of Health financed by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and was co-funded by the European Social Fund+ (ESF+) (JR23/00050, MV22/00058, CM21/00017); ISCIII (PI21/00340, PI21/00169); Milken Family Foundation (PI046998); Fundació Clínic per a la Recerca Biomèdica (FCRB) – Pons Bartan 2020 grant (PI04/6549), Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental (SEPSM); Fundació Vila Saborit; and Societat Catalana de Psiquiatria i Salut Mental (SCPiSM). Miquel Bioque thanks the support granted by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI20/01066), Fundació La Marató de TV3 (202206-30-31) and Pons-Bartran legacy (FCRB_IPB1_2023). Silvia Amoretti has been supported by Sara Borrell doctoral program (CD20/00177) and M-AES mobility fellowship (MV22/00002), from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), and co-funded by the European Social Fund “Investing in your future”. Silvia Amoretti thanks support coming from the Spanish Ministry of Innovation and Science (PI24/00671), funding from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and co-funding from the European Union (FEDER) “Una manera de hacer Europa” and La Marató-TV3 Foundation grants (202234-32). Vicent Llorca-Bofí thanks support granted by Fundación Española de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental; and Fundació Vila Saborit.