With almost one million deaths due to suicide every year, decreasing suicide rates is a priority issue for public health.1 Poor sleep quality is not among the risk factors for suicide recognized by the World Health Organization, but there is strong evidence supporting the link between suicide and sleep and recent research revealed sleep difficulties as a proximal risk factor for suicidal behavior.2–5

In this study we used Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) to: (1) measure the intra-subject correlations between sleep satisfaction and wish to live/wish to die, (2) assess their stability over time, and (3) explored the intra-subject correlations between sleep quality and wish to live/wish to die.

Participants were 127 Spanish patients included in a suicide prevention program, approached during the first year (January 2018–January 2019) of the SmartCrisis study6 (mean age=42.5, 66.1% females). An EMA app6 downloaded into their smartphones was used to asked them about death wishes, negative feelings, sleep and appetite throughout follow-up.7 Sleep-related questions were asked in the early morning whereas rest of questions were asked randomly during the day.

We calculated intra-subject correlations between wish to live/die and sleep-related questions by fitting random-effects linear models8 and examined the stability over time of the intra-subject correlation between sleep satisfaction and wish to live by computing moving correlations within a 30-day time window and plotting them as a function of the 1st day of the time window (Fig. 1). The time variable for a subject was computed as the number of days that passed after the subject was asked for the first time either the question assessing sleep satisfaction or the question assessing wish to live, whichever was asked first. We conducted an analogous time stability analysis of the intra-subject correlation between sleep satisfaction and wish to die (Fig. 2).

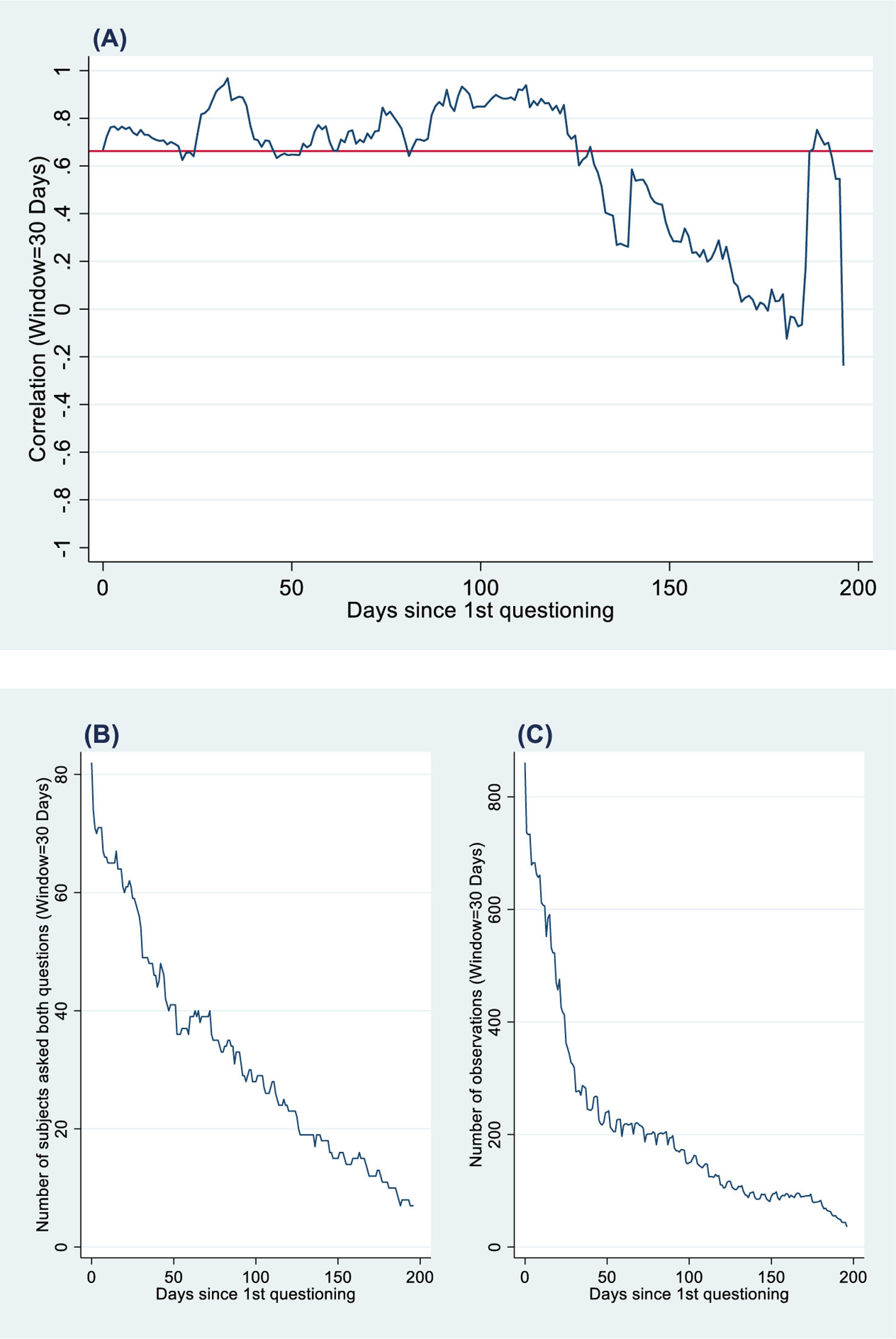

Correlations between sleep satisfaction and wish to live. (A) Moving intra-subject correlations between sleep satisfaction and wish to live computed within 30-day observation windows, versus the 1st day of the window, where days were counted from the 1st day that the subject was asked the sleep satisfaction or the life desire question. Day 0 corresponds to the first day the subject was asked a question evaluating either sleep satisfaction or desire to live. (B) Total number of subjects used to compute the correlations versus the 1st day of the window. (C) Total number of responses from these subjects either to the sleep satisfaction or life wish question, versus the 1st day of the window (i.e. the number of observations used to calculate the correlations).

Correlations between sleep satisfaction and death wish. (A) Moving intra-subject correlations between sleep satisfaction and death wish computed within 30-day observation windows, versus the 1st day of the window, where days were counted from the 1st day that the subject was asked the sleep satisfaction or the death wish question. Day 0 corresponds to the first day the subject was asked a question evaluating either sleep satisfaction or death wish. (B) Total number of subjects used to compute the correlations versus the 1st day of the window. (C) Total number of responses from these subjects either to the sleep satisfaction or death wish question, versus the 1st day of the window (i.e. the number of observations used to calculate the correlations).

The median observation time was 89.7 days. The median number of answers/participant was 110.4 (range=1–657). The mean number of wish to live questions responded was 34.08 (95% CI 50.9–60.4; 117 participants answered at least once); the mean number of wish to die questions responded was 14.7 (95% CI 26.9, 36.8; 107 answered at least once); and the mean number of sleep satisfaction questions responded was 51.6 (95% CI 46.9, 56.2; 94 answered at least once). Wish to die and wish to live showed a high negative intra-subject correlation across time [r=−0.89; 95% CI (−0.94, −0.81); p<0.001].

We studied the stability of the intra-subject correlation between sleep satisfaction and wish to live (Fig. 1), and wish to die (Fig. 2) over time. Figs. 1A and 2A show moving intra-subject correlations computed with data collected within a 30-day observation window, versus the 1st day of the window. Time 0 for a subject was the day on which one of the two questions was asked for the first time.

Fig. 1B shows the number of participants that were asked both questions during the time window and Fig. 1C shows the total number of responses to both questions versus the 1st day of the window, that is, the number of observations used to compute the correlation in Fig. 1A. The red line in Fig. 1A represents the correlation for all participants and observations, namely 0.66 (Table 1). Fig. 1A shows that the moving correlations remained relatively stable until approximately day 130, when start to show higher volatility. This may be explained in part by the decrease in the number of participants and observations as the 30-day observation window moved forward in time (Fig. 1B and C).

Overall means of the intra-subject means of responses to EMA questions.

| Question number | Question† | Overall mean response‡(n, N) | 95% CI | Lowest individual mean response§ | Highest individual mean response§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Today my wish to live is… | 55.6n=117, N=1,164 | (50.9, 60.4) | 2.8 | 98.3 |

| 8 | Today my wish to die is… | 31.9n=107, N=869 | (26.9, 36.8) | 1.8 | 94.5 |

| 22 | Today I am satisfied with my sleep. | 51.6n=94, N=683 | (46.9, 56.2) | 15.6 | 92.7 |

| 19 | Currently other people think that sleeping difficulties affect my quality of life. | 48.7n=98, N=680 | (43.3, 54.1) | 4.2 | 93.8 |

| 25 | Today I feel fatigue during the day caused by my sleeping difficulties. | 51.3n=93, N=677 | (46.1, 56.5) | 8.5 | 89.6 |

| 21 | Overall, the quality of my sleep is… | 55.0n=90, N=679 | (50.1, 59.8) | 15.0 | 94.9 |

| 20 | Overall, when I wake up I feel… | 49.0n=93, N=679 | (43.9, 54.1) | 3.6 | 95.0 |

CI: confidence interval; n: number of subjects who responded to the corresponding question at least once; N: total number of responses to the question.

The overall mean response to a question was computed by fitting the random intercept linear model corresponding to that question. For instance, if yij was the response to EMA Question 7 from subject i at occasion j, the model yij=αi+ɛij was fitted by using all available responses to Question 7 from all subjects. The overall mean response to Question 7 is an estimate of the population mean of αi, the fixed effect of the intercept.

Best linear unbiased predictors (BLUPs) were used to compute the individual mean responses for all subjects. For instance, for Question 7, the individual mean response of subject i is αi and the BLUP of αi was obtained. The minimum and maximum of the predicted αi's are reported in the table. For instance, out of the 117 subjects who responded to Question 7, the subject with the weakest wish to live had a mean response of 2.8, whereas the subject with the strongest wish had a mean response of 98.3.

Fig. 2B and C shows the number of participants and the number of responses contributing to correlations, respectively, versus the 1st day of the window. The red line represents the correlation between sleep satisfaction and death wish for all participants and observations, namely −0.69 (Table 1). Fig. 2A shows that the correlations tended to return to −0.69. The volatility of the correlation increased with time, which is probably explained by the decrease in the number of participants and observations with time (Fig. 2B and C). Overall, Fig. 2A suggests that the intra-subject correlation between sleep satisfaction and death wish is very stable over time.

We found, using EMA and random-effects linear models, that self-reported low sleep satisfaction is highly and stably related to death and life wishes. On one hand, this is of special interest for clinicians as it highlights the importance of assessing sleep as part of suicide monitoring. On the other hand, our study adds to the growing evidence of the usefulness of EMA methodology in suicidology research.9 Overall, we believe that EMA tools can be part of a paradigm shift from the traditional identification of risk factors for suicide to personalized monitoring and prevention strategies tailored to individual patients.

FundingThis article received grant support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII PI13/02200; PI16/01852), Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional de Drogas (20151073), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (LSRG-1-005-16), the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (RTI2018-099655-B-I00; TEC2017-92552-EXP), the Comunidad de Madrid (Y2018/TCS-4705, PRACTICO-CM), and by Convocatoria de ayudas para la contratación de investigadores predoctorales e investigadores postdoctorales co-funded by Fondo Social Europeo through Programa Operativo de Empleo Juvenil and Iniciativa de Empleo Juvenil (YEI) (PEJD-2018-PRE/SAL-8417).

Authors’ contributionsFrancisco J. Diaz: Formal analysis; Software; Visualization; Writing – reviewing and editing. María L. Barrigón: Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing – original draft preparation. Ismael Conejero: Methodology; Writing – reviewing and editing. Alejandro Porras-Segovia: Investigation; Methodology; Writing – reviewing and editing. Jorge Lopez-Castroman: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing – reviewing and editing. Philippe Courtet: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Writing – reviewing and editing. Jose de Leon: Supervision; Methodology; Writing – reviewing and editing. Enrique Baca-García: Conceptualization; Data curation; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Reviewing and editing.

Conflict of interestEnrique Baca-García designed the MEmind application. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statementData available under request.

The authors acknowledge Lorraine Maw, M.A., at the Mental Health Research Center at Eastern State Hospital, Lexington, KY, who helped in editing this article.