In recent decades, there has been growing interest in treatment-resistant mental disorders: schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder. The concept of refractoriness is based on a correct diagnosis, adequate therapeutic monitoring (at least two different psychotropic drugs in sufficient time and dose), and an inadequate or insufficient response. It is estimated that these disorders represent between 20% and 60% of all mental disorders, leading to a greater care burden and higher direct and indirect health care costs.1

In recent years, promising approaches have emerged for these disorders. Those associated with the field of neuromodulation have gained relevance2, while others that seemed to have faded into the background, such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), clozapine, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), are being re-emphasized.3 However, complex case reports continue to arise in practice that do not show substantial improvement with any of these approaches, maintaining persistent psychopathology and progressive functional deterioration.

Because of this, the traditional concept of “treatment-resistant mental disorder” is increasingly being questioned. This has led to the emergence of new terminology, such as “difficult-to-treat mental disorder”.4 This broader concept encompasses resistance to pharmacotherapy, neuromodulation techniques (e.g., ECT, transcranial magnetic stimulation, (es)ketamine), or psychotherapy, but also includes other confounding factors that complicate treatment. These factors include comorbidities, addictions, socioeconomic challenges, lack of adherence to treatment and more. Furthermore, the “difficult-to-treat” paradigm emphasizes a long-term management approach aimed at reducing the individual's subjective burden. This is achieved through optimizing symptom control, maximizing functionality and quality of life, and minimizing treatment-related adverse effects when remission is not attainable.5

Despite the comprehensiveness and promise of this approach, situations may arise where the strategies proposed by the “difficult-to-treat” concept prove insufficient or are simply rejected by the patient. This rejection may stem from a lack of illness awareness or a persistent refusal to accept their current situation or prognosis, often in pursuit of an idealized, unattainable recovery. Considering these challenges, we propose exploring the concept of palliative psychiatry.

The term “palliate” originates from the Latin palliāre, meaning “to cloak or cover with a mantle.” Through its semantic evolution, it has come to signify the mitigation, softening, or attenuation of something negative.

Applying this conceptual framework to mental health care, palliative psychiatry is founded on several core pillars.6 These include symptom minimization and quality-of-life enhancement – achieved by adjusting expectations and prioritizing subjective well-being; harm reduction – aimed at mitigating the negative consequences of both the disorder and its treatment; comprehensive and compassionate accompaniment – emphasizing the therapeutic relationship beyond pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic outcomes; and a person-centered approach – promoting shared decision-making grounded in dignity and autonomy.

This approach could complement the current model by offering an alternative for refractory cases where the recovery model is not feasible for the abovementioned reasons. Thus, the aim is not necessarily symptomatic remission (e.g., anhedonia, suicidal ideation, hallucinations, delusions) but rather to minimize their impact and the suffering they cause.7 To achieve this, it is essential to embrace the core principles of care: attitude, behavior, compassion, and dialogue.8 Both the patient and the therapist must accept the chronicity of the condition, yet without succumbing to nihilistic conformity. In fact, recent studies have highlighted the importance of existential dimensions, such as purpose in life,9 in influencing the emergence of psychopathology, thus highlighting the importance of including existential care in treatment.

Another key aspect is avoiding therapeutic overreach, often driven by using complex pharmacological regimens with limited efficacy and potentially significant side effects.7 Palliative psychiatry does not aim for indiscriminate deprescription, but rather seeks a personalized and simplified treatment strategy, focused on the core symptoms rather than the disorder per se. This also involves addressing comorbidities that critically influence prognosis, such as chronic pain, personality disorders, or addictions. In this regard, a multidisciplinary approach is essential – one that incorporates psychotherapies aimed at coexisting with symptoms (e.g., Acceptance and Commitment Therapy), psychoeducation, mutual aid groups, and non-curative psychosocial interventions such as therapeutic accompaniment and community-based care. In other words, the goal is not to limit therapeutic effort, but to mitigate unnecessary prescriptions and reduce futile interventions.10

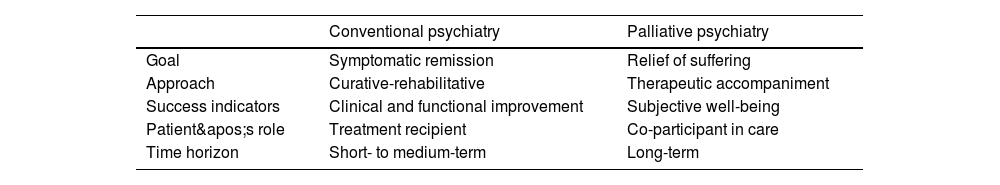

Among the most suitable cases for this approach are those where a sufficient number of therapeutic interventions (pharmacological, neuromodulatory, psychotherapeutic, community-based) have been tried adequately and over a reasonable period of time without significant clinical improvement, and where severe suffering continues to affect basic functioning.6 Palliative psychiatry may also benefit patients in states of therapeutic exhaustion or those for whom remaining treatment options carry more risks than benefits, such as intolerable side effects. Ultimately, this model is appropriate when there is shared recognition among the patient, their family, and the therapeutic team that full recovery is no longer a realistic goal (Table 1).

Structural differences between the conventional and palliative frameworks.

| Conventional psychiatry | Palliative psychiatry | |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Symptomatic remission | Relief of suffering |

| Approach | Curative-rehabilitative | Therapeutic accompaniment |

| Success indicators | Clinical and functional improvement | Subjective well-being |

| Patient's role | Treatment recipient | Co-participant in care |

| Time horizon | Short- to medium-term | Long-term |

Furthermore, palliative psychiatry raises several critical ethical dilemmas: When is it prudent to stop pursuing new treatments? How can shared decision-making be promoted when patients’ preferences diverge from the medical ideal of cure? Where is the boundary between palliative care and therapeutic abandonment? And what is the value of a life profoundly limited by mental suffering?

Palliative psychiatry is not a new paradigm that seeks to replace the current model, nor a subspecialty that requires specialized units. Rather, it is a complementary model representing a shift in mindset that can be used as a tool in clinical practice and implemented in any mental health service. This approach should be considered a legitimate therapeutic option throughout the clinical course of a patient. It calls for specific training in logotherapy, empathetic communication, existential suffering, burnout prevention, and support in chronic hopelessness.6

Having said that, this model is not without limitations. It may risk encouraging therapeutic nihilism in cases where unexplored strategies might still be effective. Additionally, as a developing field, it currently lacks robust protocols and definitive evidence, making it difficult to clearly establish criteria for identifying cases unlikely to improve.

In conclusion, palliative psychiatry must rest on rigorous assessment, ethically grounded decision-making, and a careful, compassionate clinical practice. It is not about giving up on care, but about caring differently – through accompaniment, humility, compassion, and an ethics centered on dignity and relief. Though its implementation raises debates and challenges, it opens a promising path for improving care for often-overlooked individuals. It also serves as a powerful reminder: the duty to alleviate suffering does not end when the possibility of cure does. Adopting this perspective invites mental health professionals to examine their own values and confront the meaning they assign to life, suffering, purpose, and death.

None.