Low levels of lighting in the natural environment are associated with sleep disturbance and depression.1 Light therapy (LT, exposure to bright artificial light and natural light) has been effectively used for the treatment of seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and demonstrated good efficacy in non-seasonal major depression (NS-MDD).2 Several studies found that greater daily exposure to natural light correlated with shorter hospital admissions in depressive patients.3 Therefore, although increased availability of daylight may be an affordable and effective alternative therapeutic strategy in depressive disorders, it is only cautiously mentioned in the clinical practice guidelines for the management of bipolar affective disorders.4 Moreover, there is little evidence on the possible differences in the amount of light that depressed vs non-depressed individuals may receive.

To shed light on this question, we analyzed the differences in light exposure between NS-MDD patients and healthy individuals. To continuously monitor light exposure and rest-activity cycles, both groups wore a Kronowise® (KW6) watch, that has been tested in chronobiological studies5 and does not interfere with the subjects’ daily routines.

MethodologyWe conducted a cross-sectional, observational design comparing patients diagnosed with NS-MDD and a control group of healthy participants recruited through the outpatients’ of a mental health clinic from January to May 2023.

Inclusion criteria: Patients older than 18 diagnosed with a current NS-MDD episode according to DSM-5 criteria and with a Montgomery-Äsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)≥24 who agreed to participate in the study.

Control group: healthy participants older than 18 with age, gender and employment situation matching those of the patients.

Exclusion criteria: Alcohol or other drug abuse showing another psychiatric or neurological disease; skin and eye sensitivity problems and/or photophobia; working on shifts.

Procedure: All participants received information and signed the informed consent form prior to being included in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics committee (approval code IB 4429/21 PI).

The 2 groups wore the KW6 on the non-dominant wrist for 24h for a total of 4 workdays. The KW6 device measures light, skin temperature, and motor activity at 30-s intervals.

Supplementary assessment: subjective depressive symptomatology with the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology self-report (QIDS-SR)6 and sleep quality with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).7

Analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0, employing the U-Mann–Whitney to assess significant differences in light intensities within circadian records across groups. Additionally, we looked into the variations in light intensity received during morning, evening, and night.

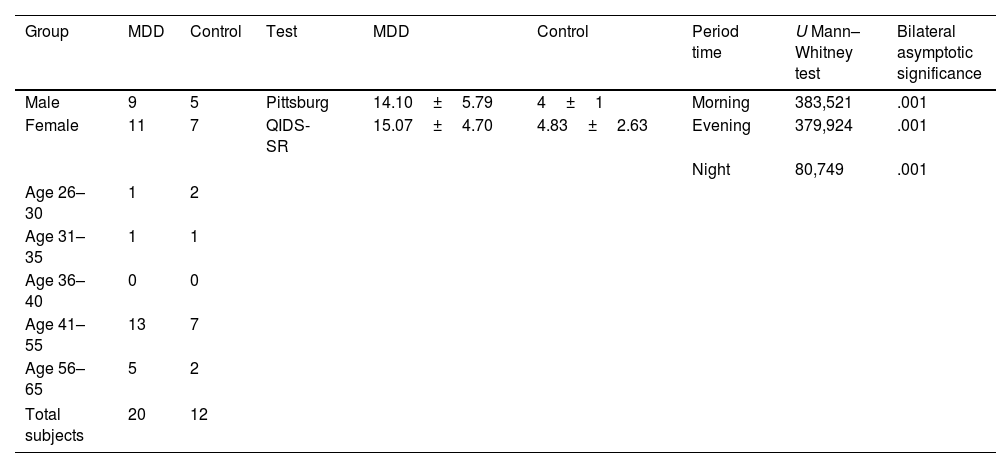

ResultsFinal recruitment included a total of 20 NS-MDD patients and 12 healthy controls. They exhibited similar gender and age distribution (41–55 y.o.; mostly women). The mean of QIDS-SR in depressive subjects was 15.07±4.70. Regarding sleep, NS-MDD had a bad sleep quality (PSQI, 14.10±5.79), while control group were good sleepers (PSQI, 4±1).

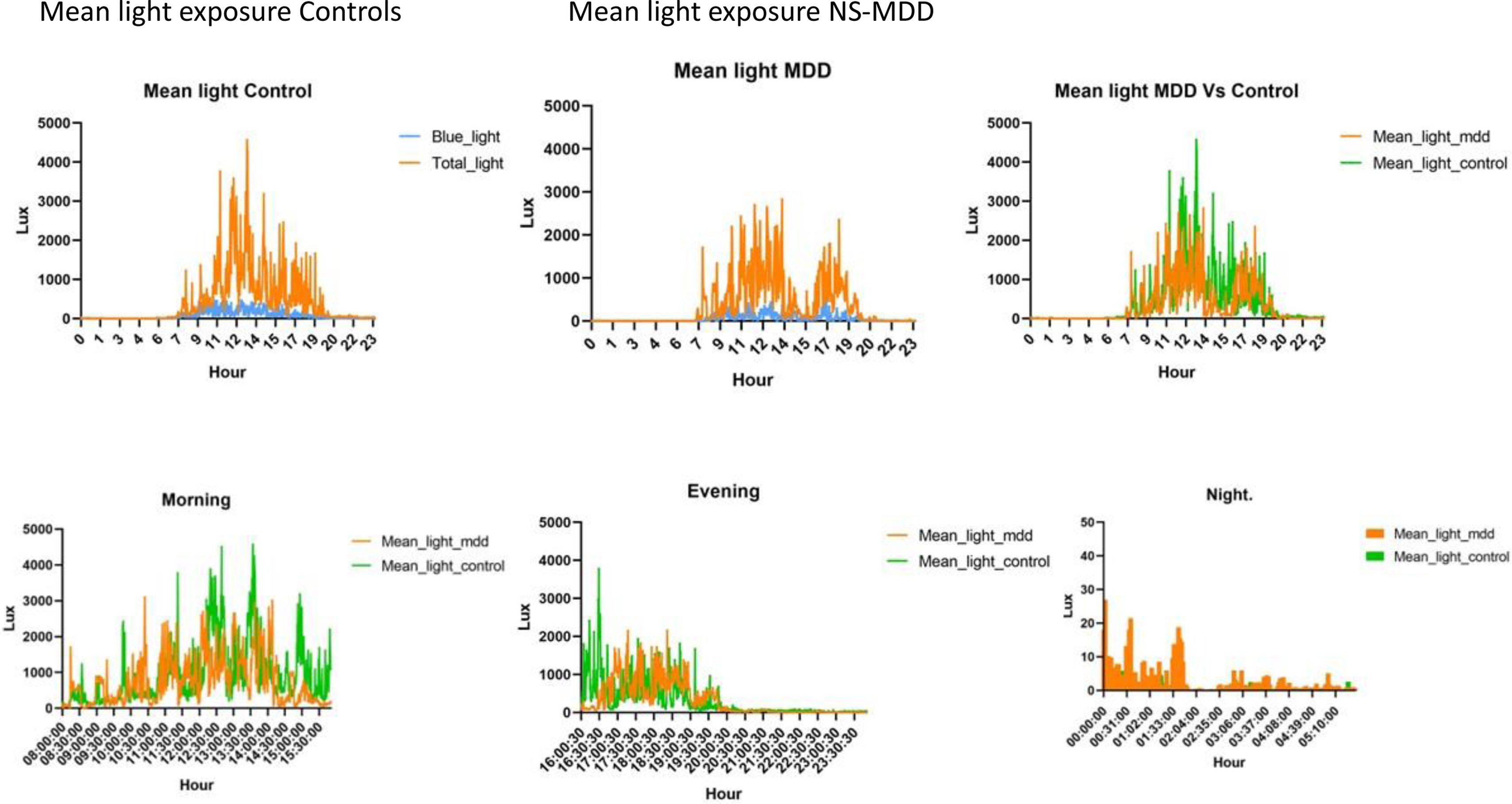

Light exposure (Lux/hour) analysis revealed a significant difference in light intensity received (U statistic=3561659, p=0.001), and distinctive circadian patterns between the 2 groups (Fig. 1). The NS-MDD group experiences lower daytime light intensity vs the control group, with a notable decrease in the afternoon at 15:00–16:00 (Table 1).

| Group | MDD | Control | Test | MDD | Control | Period time | U Mann–Whitney test | Bilateral asymptotic significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 9 | 5 | Pittsburg | 14.10±5.79 | 4±1 | Morning | 383,521 | .001 |

| Female | 11 | 7 | QIDS-SR | 15.07±4.70 | 4.83±2.63 | Evening | 379,924 | .001 |

| Night | 80,749 | .001 | ||||||

| Age 26–30 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Age 31–35 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Age 36–40 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Age 41–55 | 13 | 7 | ||||||

| Age 56–65 | 5 | 2 | ||||||

| Total subjects | 20 | 12 | ||||||

The aim of this pilot study was to investigate whether there are any differences in the amount of daylight to which patients with depression are exposed vs healthy controls to better understand the role of light in affective disorders.

The study revealed that NS-MDD patients received significantly lower total light intensity than controls. The nuanced analysis indicates significant differences (<0.005) in light intensity means between both groups during morning, evening, and night. Controls receive higher light intensity in morning and during the evening. However, at night, depressive patients receive higher light intensity levels. This finding is consistent with a previous research8 where depressive subjects exhibited greater activity online vs non depressed subjects. Therefore, the increased exposure of light could be due to the exposure to electronic devices. In addition, and with findings consistent with the study conducted by Obayashi,9 a correlation of light exposure at night was found with depressive symptoms. Both increased exposure to light and the use of technology can be a consequence of the increased sleep fragmentation observed in depressive patients. In addition, a similar dip in light exposure during the afternoon than that observed in the NS-MDD group was found in women with SAD during winter.10

In conclusion, depressive patients receive lower total daylight intensity and have different circadian patterns vs healthy subjects. These results provide information for future research on correlations of depressive mood with light during day and night in larger samples. In addition, it opens the possibilities for targeted light interventions in mood disorders.

Transparency statementThe senior author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being submitted, and that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

We wish to thank the patients and volunteers who generously participate in this study, as well as the staff from the Mental Health Unit for their collaboration in the clinical development of the research.