Psycho-COVID: Long-term effects of COVID19 pandemic on brain and mental health

Más datosHealth care workers (HCW) have been identified as a risk group to suffer psychological burden derived from Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic. In addition, possible gender differences in the emotional reactions derived from COVID-19 pandemic have been suggested in this population. The aims of the study were to explore the impact of COVID-19 as well as possible gender differences on mental health status and suicidality in a cohort of HCW.

Materials and methodsOne thousand four hundred and thirty-two HCW responded to an online survey including sociodemographic, clinical, and psychometric tests in May 2020 while 251 HCW answered in November 2020. Mental health status was measured by General Health Questionnaire 28 (GHQ-28) in both time periods.

ResultsHCW informed of a worsening in somatic symptomatology over the follow up period. Gender differences were found in all GHQ-28 dimensions as well in the total score of the questionnaire. Post hoc analyses displayed significant interaction between the time and gender in somatic and anxiety dimensions as well as in GHQ-28 total score. Stress produced by COVID-19 spreading and the feeling of being overwhelmed at work resulted the main predictors of psychological distress although each domain is characterized by a specific set of predictors.

ConclusionsSomatic reactions represent the most sensitive dimension over the follow-up period. Moreover, women are characterized by a greater psychological distress at the beginning, although these differences tend to disappear over time. Finally, a complex network of factors predicted different dimensions of psychological distress, showing the complexity of prevention in high-risk populations facing major disasters.

Los trabajadores sanitarios (TS) han sido identificados como un grupo vulnerable de sufrir consecuencias emocionales derivadas de la pandemia causada por la COVID-19. Además, se han sugerido posibles diferencias de género en las reacciones emocionales derivadas del afrontamiento de la pandemia. Los objetivos del estudio fueron explorar el impacto de la COVID-19, así como posibles diferencias de género en las reacciones emociones derivadas de la COVID-19 en una cohorte de TS.

Materiales y métodosUn total de 1.432 TS respondieron a una encuesta en línea que incluía preguntas referidas a datos sociodemográficos, clínicos y psicométricos en mayo de 2020, mientras que 251 TS respondieron en noviembre de 2020. El estado de salud mental se midió mediante el Cuestionario de Salud General 28 (General Health Questionnaire 28 [GHQ-28]) en ambos periodos de tiempo.

ResultadosLos TS informaron de un empeoramiento de la sintomatología somática. Se encontraron diferencias de género en todas las dimensiones del GHQ-28. Los análisis post hoc mostraron una interacción significativa entre el tiempo y el género en las dimensiones somáticas y de ansiedad, así como en la puntuación total del GHQ-28. El estrés producido por ser fuente de infección y la sensación de agobio en el trabajo resultaron ser los principales predictores del malestar psicológico, aunque cada dominio se caracteriza por un conjunto específico de predictores.

ConclusionesLas reacciones somáticas representan la dimensión más sensible. Además, las mujeres se caracterizan por un mayor malestar psicológico al principio, aunque estas diferencias tienden a desaparecer con el tiempo. Por último, una compleja red de factores predijo las diferentes dimensiones de la angustia psicológica.

The recent pandemic caused by Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) has caused adverse effects on mental health status of general population and especially on health-care workers (HCW).1,2 It is a matter of interest to analyze the short-term and long-term consequences on the mental health status of the workers coping with major disasters.3

Recent investigations have explored the potential consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health status of the HCW. In particular, it has been suggested that the prevalence of depression among HCW facing COVID-19 is between 15–36%, 28–38% report anxiety and 25–46% complain of sleep problems.4–8 These consequences usually lead to relinquishment from job, occupational inability periods and poorer performance.4 Due to the temporal persistence of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as its wave-like progression, longitudinal studies are warranted to understand the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health status of HCW.

Cross sectional studies informed that women seems to suffer higher rates of trauma-related distress, anxiety and depression symptoms, decreased frustration tolerance and lower quality of sleep accompanied by an increase of hypnotic medication use.9 Precisely, it has been recently published a longitudinal cohort study of HCW facing COVID-19 showing that women reported more stress than men at the beginning of the follow-up period but these significant gender differences disappeared at the end of the follow-up period.10 Fenollar-Cortés et al. (2021) reported similar results in a longitudinal study in a sample of general population.11

HCW have been identified as a risk group for suicidal behaviour.12 Recently, and contrary to most of the studies published so far,13 in a study carried out in United States analysing a period prior to COVID-19, only nurses were characterized by a significant higher suicide risk compared with general population.14 Since the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a growing interest in the possible role that the pandemic caused by COVID-19 could play as a suicidal risk factor among HCW. In fact, a systematic review on the subject highlighted the paucity evidence existing about the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicidality among HCW.15

Diverse studies have explored potential psychological distress predictors among HCW facing the outbreak produced by COVID-19 pandemic.16 An array set of predictors have been recognized including sociodemographic, occupational, social, and psychological.17 However, those factors that are properly related to infection exposure such as poor working conditions (lack of biosafety equipment and control systems, excessive working loadout, critical events exposure), fear of infecting their relatives or being infected, scarce of incentives and recognition and lifestyle conditions have been identified as the main risk factors of psychological distress in HCW.15,18 A recent systematic review showed that female gender, work as nurse, experiencing stigma, maladaptive coping strategies, having contact or risk of contact with patients infected by COVID-19 as well as experiencing quarantine were the most relevant risk factors to suffer psychological distress among this population.19–21

The main aim of the present study was to analyze the impact of the COVID-19 on the psychological well-being and suicidality in a longitudinal cohort sample of different types of HCW. Secondly, we aimed to explore how the pandemic situation could have affected unequally depending on the gender. Finally, using multivariate analyses we sought out to identify potential predictors of psychological distress as well as suicidal thoughts including for this purpose a comprehensive set of sociodemographic, clinical, and work conditions factors.

Materials and methodsParticipants were contacted and enlightened about study objectives using e-mail lists and professional WhatsApp. All participants gave their digital informed consent and responded to the survey using exclusively Google Forms. The data were anonymized. Surveys were sent in two different timepoints (May 2020 and November 2020). On May 8, 2020 the number of daily cases of COVID-19 in Spain reached the amount of 1.095, while on November 9, 2020 there were 16.819 new cases of COVID-19. On May 8, 2020 237 deaths were registered, while on November 9, 2020 there were 170 deaths. The study was approved by the local ethics committee in accordance with international standards for research ethics (Registration number removed). This study was not funded.

The Spanish National Health Service is administered by each of the autonomous communities that make up the Spanish state. There are 17 autonomous communities and 2 autonomous cities in Spain. The respondents who answered to the survey were working in 16 different health public systems administered by their autonomous communities as follows: Andalucía (853, 59.57%); Aragón (25, 1.75%); Asturias (7, 0.49%); Baleares (31, 2.16%); Canarias (9, 0.63%); Cantabria (109, 7.61%); Castilla la Mancha (19, 1.32%); Castilla y León (67, 4.68%); Cataluña (75, 5.24%); Comunidad Valenciana (32, 2.23%); Extremadura (24, 1.68%); Galicia (38, 2.65%); Madrid (120, 8.38%); Navarra (4, 0.28%); Pais Vasco (16, 1.12%); La Rioja (3, 0.21%). No HCW from Comunidad de Murcia or the autonomous cities (Ceuta y Melilla) responded to the survey.

Based on data obtained from the National Institute of Statistics of Spain approximately the 52,8% of physician and the 84,2% of nurses are women.22 In our study, 72,8% of respondents were women. According to the Medical Syndicate of Spain, the mean age of the active doctors in 2018 was approximately 49.2 years, while the mean age of respondents was 44.8 years.23 It is difficult to assess if the sample is representative for Spanish HCW due to a lack of joint information as the statistics found gather data of each specific professional group, while our descriptive analysis focus on the aggregate of all of them. However, the pattern showed by the sources consulted is in keeping with our sample.

MeasuresSociodemographic information such as gender, age, civil status, province of residence, clinical service in which the people worked, or occupational category was recorded throughout proforma designed for the study. In addition, information regarding mental health was also included in the proforma questionnaire (e.g., history of mental health disorder, stress, anxiety, and depression associated with COVID-19, traumatic experiences over pandemic period) as well as COVID-19 exposure, coping strategies during pandemic and COVID-19 risk perception. See Table 1.

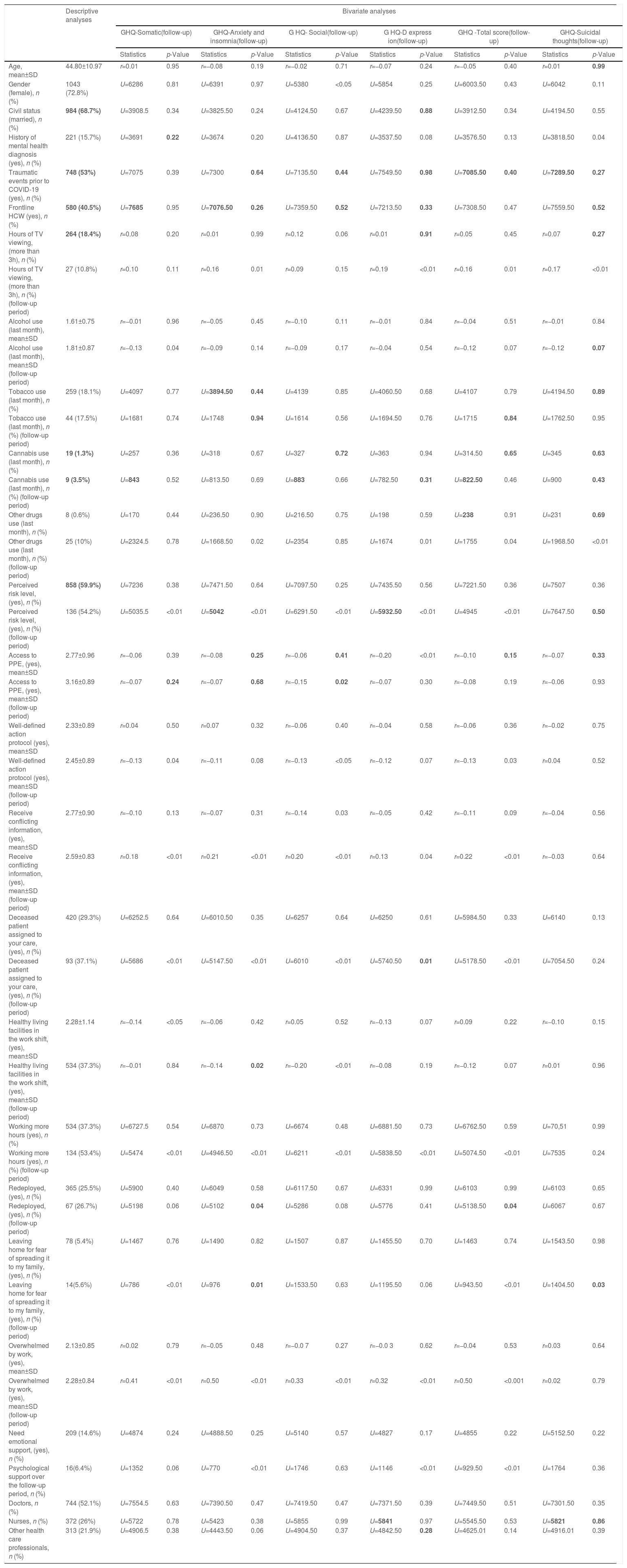

Descriptive and bivariate analyses.

| Descriptive analyses | Bivariate analyses | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHQ-Somatic(follow-up) | GHQ-Anxiety and insomnia(follow-up) | G HQ- Social(follow-up) | G HQ-D express ion(follow-up) | GHQ -Total score(follow-up) | GHQ-Suicidal thoughts(follow-up) | ||||||||

| Statistics | p-Value | Statistics | p-Value | Statistics | p-Value | Statistics | p-Value | Statistics | p-Value | Statistics | p-Value | ||

| Age, mean±SD | 44.80±10.97 | r=0.01 | 0.95 | r=−0.08 | 0.19 | r=−0.02 | 0.71 | r=−0.07 | 0.24 | r=−0.05 | 0.40 | r=0.01 | 0.99 |

| Gender (female), n (%) | 1043 (72.8%) | U=6286 | 0.81 | U=6391 | 0.97 | U=5380 | <0.05 | U=5854 | 0.25 | U=6003.50 | 0.43 | U=6042 | 0.11 |

| Civil status (married), n (%) | 984 (68.7%) | U=3908.5 | 0.34 | U=3825.50 | 0.24 | U=4124.50 | 0.67 | U=4239.50 | 0.88 | U=3912.50 | 0.34 | U=4194.50 | 0.55 |

| History of mental health diagnosis (yes), n (%) | 221 (15.7%) | U=3691 | 0.22 | U=3674 | 0.20 | U=4136.50 | 0.87 | U=3537.50 | 0.08 | U=3576.50 | 0.13 | U=3818.50 | 0.04 |

| Traumatic events prior to COVID-19 (yes), n (%) | 748 (53%) | U=7075 | 0.39 | U=7300 | 0.64 | U=7135.50 | 0.44 | U=7549.50 | 0.98 | U=7085.50 | 0.40 | U=7289.50 | 0.27 |

| Frontline HCW (yes), n (%) | 580 (40.5%) | U=7685 | 0.95 | U=7076.50 | 0.26 | U=7359.50 | 0.52 | U=7213.50 | 0.33 | U=7308.50 | 0.47 | U=7559.50 | 0.52 |

| Hours of TV viewing, (more than 3h), n (%) | 264 (18.4%) | r=0.08 | 0.20 | r=0.01 | 0.99 | r=0.12 | 0.06 | r=0.01 | 0.91 | r=0.05 | 0.45 | r=0.07 | 0.27 |

| Hours of TV viewing, (more than 3h), n (%) (follow-up period) | 27 (10.8%) | r=0.10 | 0.11 | r=0.16 | 0.01 | r=0.09 | 0.15 | r=0.19 | <0.01 | r=0.16 | 0.01 | r=0.17 | <0.01 |

| Alcohol use (last month), mean±SD | 1.61±0.75 | r=−0.01 | 0.96 | r=−0.05 | 0.45 | r=−0.10 | 0.11 | r=−0.01 | 0.84 | r=−0.04 | 0.51 | r=−0.01 | 0.84 |

| Alcohol use (last month), mean±SD (follow-up period) | 1.81±0.87 | r=−0.13 | 0.04 | r=−0.09 | 0.14 | r=−0.09 | 0.17 | r=−0.04 | 0.54 | r=−0.12 | 0.07 | r=−0.12 | 0.07 |

| Tobacco use (last month), n (%) | 259 (18.1%) | U=4097 | 0.77 | U=3894.50 | 0.44 | U=4139 | 0.85 | U=4060.50 | 0.68 | U=4107 | 0.79 | U=4194.50 | 0.89 |

| Tobacco use (last month), n (%) (follow-up period) | 44 (17.5%) | U=1681 | 0.74 | U=1748 | 0.94 | U=1614 | 0.56 | U=1694.50 | 0.76 | U=1715 | 0.84 | U=1762.50 | 0.95 |

| Cannabis use (last month), n (%) | 19 (1.3%) | U=257 | 0.36 | U=318 | 0.67 | U=327 | 0.72 | U=363 | 0.94 | U=314.50 | 0.65 | U=345 | 0.63 |

| Cannabis use (last month), n (%) (follow-up period) | 9 (3.5%) | U=843 | 0.52 | U=813.50 | 0.69 | U=883 | 0.66 | U=782.50 | 0.31 | U=822.50 | 0.46 | U=900 | 0.43 |

| Other drugs use (last month), n (%) | 8 (0.6%) | U=170 | 0.44 | U=236.50 | 0.90 | U=216.50 | 0.75 | U=198 | 0.59 | U=238 | 0.91 | U=231 | 0.69 |

| Other drugs use (last month), n (%) (follow-up period) | 25 (10%) | U=2324.5 | 0.78 | U=1668.50 | 0.02 | U=2354 | 0.85 | U=1674 | 0.01 | U=1755 | 0.04 | U=1968.50 | <0.01 |

| Perceived risk level, (yes), n (%) | 858 (59.9%) | U=7236 | 0.38 | U=7471.50 | 0.64 | U=7097.50 | 0.25 | U=7435.50 | 0.56 | U=7221.50 | 0.36 | U=7507 | 0.36 |

| Perceived risk level, (yes), n (%) (follow-up period) | 136 (54.2%) | U=5035.5 | <0.01 | U=5042 | <0.01 | U=6291.50 | <0.01 | U=5932.50 | <0.01 | U=4945 | <0.01 | U=7647.50 | 0.50 |

| Access to PPE, (yes), mean±SD | 2.77±0.96 | r=−0.06 | 0.39 | r=−0.08 | 0.25 | r=−0.06 | 0.41 | r=−0.20 | <0.01 | r=−0.10 | 0.15 | r=−0.07 | 0.33 |

| Access to PPE, (yes), mean±SD (follow-up period) | 3.16±0.89 | r=−0.07 | 0.24 | r=−0.07 | 0.68 | r=−0.15 | 0.02 | r=−0.07 | 0.30 | r=−0.08 | 0.19 | r=−0.06 | 0.93 |

| Well-defined action protocol (yes), mean±SD | 2.33±0.89 | r=0.04 | 0.50 | r=0.07 | 0.32 | r=−0.06 | 0.40 | r=−0.04 | 0.58 | r=−0.06 | 0.36 | r=−0.02 | 0.75 |

| Well-defined action protocol (yes), mean±SD (follow-up period) | 2.45±0.89 | r=−0.13 | 0.04 | r=−0.11 | 0.08 | r=−0.13 | <0.05 | r=−0.12 | 0.07 | r=−0.13 | 0.03 | r=0.04 | 0.52 |

| Receive conflicting information, (yes), mean±SD | 2.77±0.90 | r=−0.10 | 0.13 | r=−0.07 | 0.31 | r=−0.14 | 0.03 | r=−0.05 | 0.42 | r=−0.11 | 0.09 | r=−0.04 | 0.56 |

| Receive conflicting information, (yes), mean±SD (follow-up period) | 2.59±0.83 | r=0.18 | <0.01 | r=0.21 | <0.01 | r=0.20 | <0.01 | r=0.13 | 0.04 | r=0.22 | <0.01 | r=−0.03 | 0.64 |

| Deceased patient assigned to your care, (yes), n (%) | 420 (29.3%) | U=6252.5 | 0.64 | U=6010.50 | 0.35 | U=6257 | 0.64 | U=6250 | 0.61 | U=5984.50 | 0.33 | U=6140 | 0.13 |

| Deceased patient assigned to your care, (yes), n (%) (follow-up period) | 93 (37.1%) | U=5686 | <0.01 | U=5147.50 | <0.01 | U=6010 | <0.01 | U=5740.50 | 0.01 | U=5178.50 | <0.01 | U=7054.50 | 0.24 |

| Healthy living facilities in the work shift, (yes), mean±SD | 2.28±1.14 | r=−0.14 | <0.05 | r=−0.06 | 0.42 | r=0.05 | 0.52 | r=−0.13 | 0.07 | r=0.09 | 0.22 | r=−0.10 | 0.15 |

| Healthy living facilities in the work shift, (yes), mean±SD (follow-up period) | 534 (37.3%) | r=−0.01 | 0.84 | r=−0.14 | 0.02 | r=−0.20 | <0.01 | r=−0.08 | 0.19 | r=−0.12 | 0.07 | r=0.01 | 0.96 |

| Working more hours (yes), n (%) | 534 (37.3%) | U=6727.5 | 0.54 | U=6870 | 0.73 | U=6674 | 0.48 | U=6881.50 | 0.73 | U=6762.50 | 0.59 | U=70,51 | 0.99 |

| Working more hours (yes), n (%) (follow-up period) | 134 (53.4%) | U=5474 | <0.01 | U=4946.50 | <0.01 | U=6211 | <0.01 | U=5838.50 | <0.01 | U=5074.50 | <0.01 | U=7535 | 0.24 |

| Redeployed, (yes), n (%) | 365 (25.5%) | U=5900 | 0.40 | U=6049 | 0.58 | U=6117.50 | 0.67 | U=6331 | 0.99 | U=6103 | 0.99 | U=6103 | 0.65 |

| Redeployed, (yes), n (%) (follow-up period) | 67 (26.7%) | U=5198 | 0.06 | U=5102 | 0.04 | U=5286 | 0.08 | U=5776 | 0.41 | U=5138.50 | 0.04 | U=6067 | 0.67 |

| Leaving home for fear of spreading it to my family, (yes), n (%) | 78 (5.4%) | U=1467 | 0.76 | U=1490 | 0.82 | U=1507 | 0.87 | U=1455.50 | 0.70 | U=1463 | 0.74 | U=1543.50 | 0.98 |

| Leaving home for fear of spreading it to my family, (yes), n (%) (follow-up period) | 14(5.6%) | U=786 | <0.01 | U=976 | 0.01 | U=1533.50 | 0.63 | U=1195.50 | 0.06 | U=943.50 | <0.01 | U=1404.50 | 0.03 |

| Overwhelmed by work, (yes), mean±SD | 2.13±0.85 | r=0.02 | 0.79 | r=−0.05 | 0.48 | r=−0.0 7 | 0.27 | r=−0.0 3 | 0.62 | r=−0.04 | 0.53 | r=0.03 | 0.64 |

| Overwhelmed by work, (yes), mean±SD (follow-up period) | 2.28±0.84 | r=0.41 | <0.01 | r=0.50 | <0.01 | r=0.33 | <0.01 | r=0.32 | <0.01 | r=0.50 | <0.001 | r=0.02 | 0.79 |

| Need emotional support, (yes), n (%) | 209 (14.6%) | U=4874 | 0.24 | U=4888.50 | 0.25 | U=5140 | 0.57 | U=4827 | 0.17 | U=4855 | 0.22 | U=5152.50 | 0.22 |

| Psychological support over the follow-up period, n (%) | 16(6.4%) | U=1352 | 0.06 | U=770 | <0.01 | U=1746 | 0.63 | U=1146 | <0.01 | U=929.50 | <0.01 | U=1764 | 0.36 |

| Doctors, n (%) | 744 (52.1%) | U=7554.5 | 0.63 | U=7390.50 | 0.47 | U=7419.50 | 0.47 | U=7371.50 | 0.39 | U=7449.50 | 0.51 | U=7301.50 | 0.35 |

| Nurses, n (%) | 372 (26%) | U=5722 | 0.78 | U=5423 | 0.38 | U=5855 | 0.99 | U=5841 | 0.97 | U=5545.50 | 0.53 | U=5821 | 0.86 |

| Other health care professionals, n (%) | 313 (21.9%) | U=4906.5 | 0.38 | U=4443.50 | 0.06 | U=4904.50 | 0.37 | U=4842.50 | 0.28 | U=4625.01 | 0.14 | U=4916.01 | 0.39 |

SD: standard deviation; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; HCW: Health Care Workers; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; PPE: Personal Protective Equipment; GHQ-28: General Health Questionnaire.

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28)24 is a self-administered screening scale which assesses 4 subscales in 28 items: (a) somatic symptoms, (b) anxiety and insomnia, (c) social dysfunction, (d) severe depression. The items are scored in a Likert-type scale 0–3 and yield a total score. The version used in this study is different from the original one featured in the early 1970s, not just in the number of items (28 versus 60), but also in the setting of 4 subscales, what enables investigators to obtain more information than a single severity score, comparing which kind of symptoms suffers more changes between two given moments.25 GHQ-28 exhibited overall Cronbach's alpha of 0.93 indicating a high degree of internal consistency.

Assessment of suicidal thoughtsSuicidal ideation was assessed by item 25 of GHQ-28: ‘Thoughts of taking your life?’ This question inquiries about active thoughts of killing oneself that is in line with the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment.26

Statistical analysesAll analyses were carried out with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 24.27 The development in each of GHQ-28 dimensions, in the total score as well as in suicidal thoughts were investigated with the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.

Repeated analyses of variance (ANOVA) adjusted by age and level of COVID-19 exposition were carried out to explore gender differences. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test examined the normality of variables. Sphericity was checked using Mauchy's W (where assumptions of sphericity were violated, a Greenhouse–Geisser adjustment was applied). Effects of time (longitudinal dimension), group (cross-sectional dimension) and time by group (interaction effect) were examined. Pairwise comparisons were conducted to examine between-groups differences at different points in time. All post hoc comparisons were Bonferroni corrected.

Multiple linear regression analyses tested the real influence of the independent variables on each subscale of the GHQ-28 as well as on the total score and the item used to evaluate suicidal thoughts. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was calculated for each regression model and there were no VIF's values over 1.41, thus the assumption of multicollinearity was not violated. The significant variables in the univariate analyses were added to the multiple linear regression models as potential predictors.

A significance level of 5% was used for all the above analyses.

ResultsSample characteristicsA total of 1432 participants answered a proforma questionnaire at baseline. From the total people who responded baseline proforma, 251 (17.53%) completed the evaluation 6 months later. Sociodemographic and clinical information are displayed in Table 1.

Development of psychological well-being and suicidal thoughts over the follow-up periodWe observed that HCW worsened significantly in GHQ-28 somatic dimension (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test: Z=−2.32; p=0.02; 8.18±4.99 vs. 8.74±5.19). No significant differences were found in the rest of the dimensions as well as in suicidal thoughts.

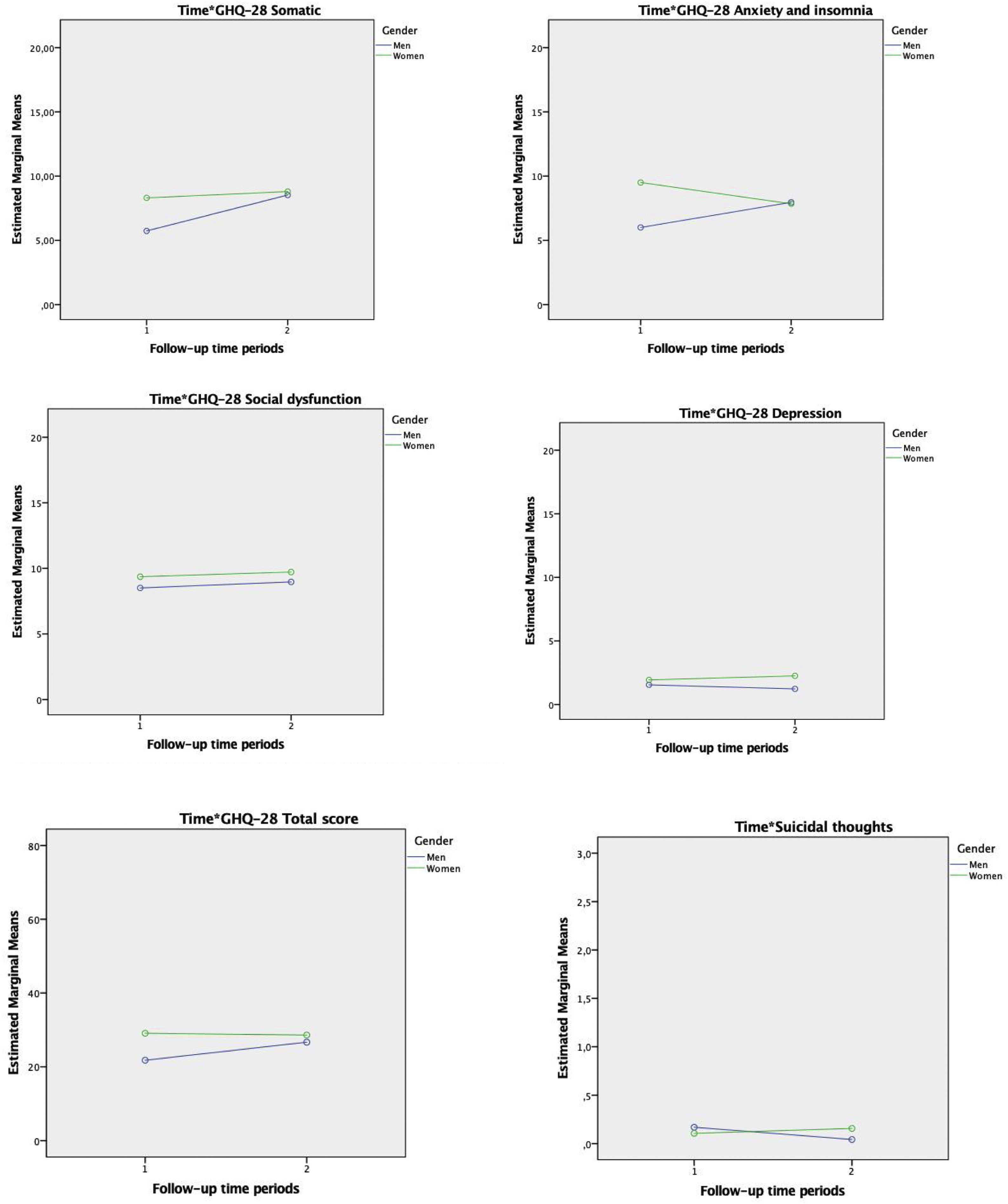

Gender differencesThe groups differed significantly in GHQ-28 somatic (F(1,246)=9.43; p<0.01), GHQ-28 anxiety and insomnia (F(1,246)=9.12; p<0.01), GHQ-28 social (F(1,246)=7.13; p<0.01), GHQ-28 depression (F(1,246)=3.98; p<0.05), and GHQ-28 total score (F(1,246)=11.88; p≤0.01). Significant time×group interactions were observed in GHQ-28 somatic (F(1,246)=5.15; p=0.02), GHQ-28 anxiety and insomnia (F(1,246)=10.85; p<0.01) as well as in GHQ-28 Total score (F(1,246)=4.16; p<0.05). No significant time, group or time×group differences were found in suicidal thoughts. See Fig. 1.

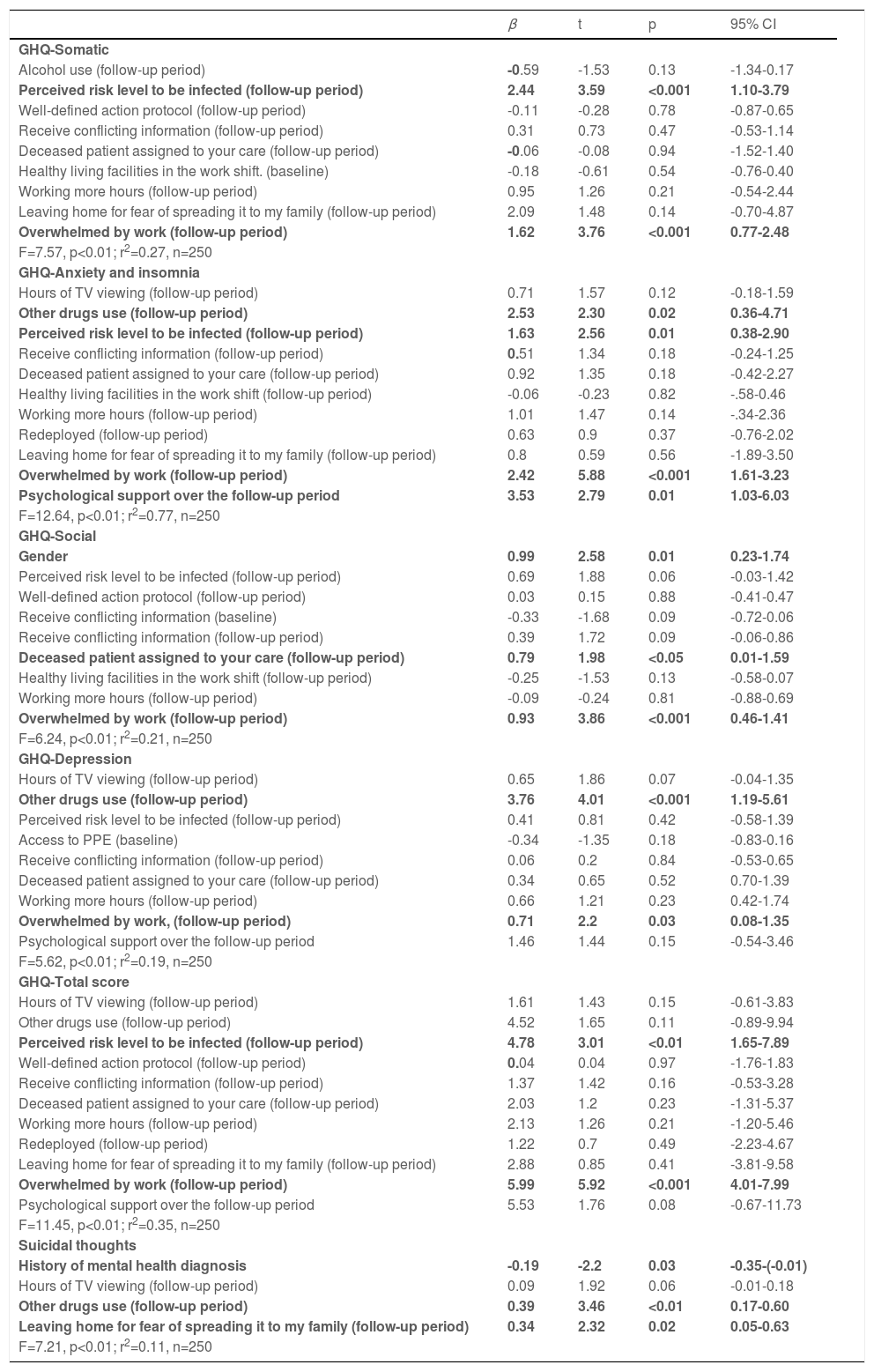

PredictorsSomatic dimension was predicted by perceived risk level to be infected at follow-up period and overwhelmed by work at follow-up period. On the other hand, anxiety and insomnia subscale was significantly associated in the multivariate model with: (i) other drugs use at follow-up, (ii) perceived risk level to be infected at follow-up period, (iii) overwhelmed by work at follow-up period and (iv) the need of psychological support over the follow-up period considered in the present study.

Multivariate analyses showed that women, those who were responsible for patients who died by COVID-19 over the follow-up period and experiencing overwhelmed feelings at work over the follow-up period showed significantly worse social functioning. Depression was predicted by other drugs use at follow-up and overwhelming feelings at work during the follow-up period while Total score of GHQ-28 was significantly associated with perceived risk level to be infected and overwhelmed by work at follow-up period.

Finally, suicidal thoughts were significant associated with absence of previous mental health diagnosis, the use of other drugs over the follow-up period and leaving home for fear of spreading COVID-19 to the family members at follow-up period. More details are shown in Table 2.

Multiple linear regression analysis for GHQ-28 as dependent variable.

| β | t | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHQ-Somatic | ||||

| Alcohol use (follow-up period) | -0.59 | -1.53 | 0.13 | -1.34-0.17 |

| Perceived risk level to be infected (follow-up period) | 2.44 | 3.59 | <0.001 | 1.10-3.79 |

| Well-defined action protocol (follow-up period) | -0.11 | -0.28 | 0.78 | -0.87-0.65 |

| Receive conflicting information (follow-up period) | 0.31 | 0.73 | 0.47 | -0.53-1.14 |

| Deceased patient assigned to your care (follow-up period) | -0.06 | -0.08 | 0.94 | -1.52-1.40 |

| Healthy living facilities in the work shift. (baseline) | -0.18 | -0.61 | 0.54 | -0.76-0.40 |

| Working more hours (follow-up period) | 0.95 | 1.26 | 0.21 | -0.54-2.44 |

| Leaving home for fear of spreading it to my family (follow-up period) | 2.09 | 1.48 | 0.14 | -0.70-4.87 |

| Overwhelmed by work (follow-up period) | 1.62 | 3.76 | <0.001 | 0.77-2.48 |

| F=7.57, p<0.01; r2=0.27, n=250 | ||||

| GHQ-Anxiety and insomnia | ||||

| Hours of TV viewing (follow-up period) | 0.71 | 1.57 | 0.12 | -0.18-1.59 |

| Other drugs use (follow-up period) | 2.53 | 2.30 | 0.02 | 0.36-4.71 |

| Perceived risk level to be infected (follow-up period) | 1.63 | 2.56 | 0.01 | 0.38-2.90 |

| Receive conflicting information (follow-up period) | 0.51 | 1.34 | 0.18 | -0.24-1.25 |

| Deceased patient assigned to your care (follow-up period) | 0.92 | 1.35 | 0.18 | -0.42-2.27 |

| Healthy living facilities in the work shift (follow-up period) | -0.06 | -0.23 | 0.82 | -.58-0.46 |

| Working more hours (follow-up period) | 1.01 | 1.47 | 0.14 | -.34-2.36 |

| Redeployed (follow-up period) | 0.63 | 0.9 | 0.37 | -0.76-2.02 |

| Leaving home for fear of spreading it to my family (follow-up period) | 0.8 | 0.59 | 0.56 | -1.89-3.50 |

| Overwhelmed by work (follow-up period) | 2.42 | 5.88 | <0.001 | 1.61-3.23 |

| Psychological support over the follow-up period | 3.53 | 2.79 | 0.01 | 1.03-6.03 |

| F=12.64, p<0.01; r2=0.77, n=250 | ||||

| GHQ-Social | ||||

| Gender | 0.99 | 2.58 | 0.01 | 0.23-1.74 |

| Perceived risk level to be infected (follow-up period) | 0.69 | 1.88 | 0.06 | -0.03-1.42 |

| Well-defined action protocol (follow-up period) | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.88 | -0.41-0.47 |

| Receive conflicting information (baseline) | -0.33 | -1.68 | 0.09 | -0.72-0.06 |

| Receive conflicting information (follow-up period) | 0.39 | 1.72 | 0.09 | -0.06-0.86 |

| Deceased patient assigned to your care (follow-up period) | 0.79 | 1.98 | <0.05 | 0.01-1.59 |

| Healthy living facilities in the work shift (follow-up period) | -0.25 | -1.53 | 0.13 | -0.58-0.07 |

| Working more hours (follow-up period) | -0.09 | -0.24 | 0.81 | -0.88-0.69 |

| Overwhelmed by work (follow-up period) | 0.93 | 3.86 | <0.001 | 0.46-1.41 |

| F=6.24, p<0.01; r2=0.21, n=250 | ||||

| GHQ-Depression | ||||

| Hours of TV viewing (follow-up period) | 0.65 | 1.86 | 0.07 | -0.04-1.35 |

| Other drugs use (follow-up period) | 3.76 | 4.01 | <0.001 | 1.19-5.61 |

| Perceived risk level to be infected (follow-up period) | 0.41 | 0.81 | 0.42 | -0.58-1.39 |

| Access to PPE (baseline) | -0.34 | -1.35 | 0.18 | -0.83-0.16 |

| Receive conflicting information (follow-up period) | 0.06 | 0.2 | 0.84 | -0.53-0.65 |

| Deceased patient assigned to your care (follow-up period) | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.70-1.39 |

| Working more hours (follow-up period) | 0.66 | 1.21 | 0.23 | 0.42-1.74 |

| Overwhelmed by work, (follow-up period) | 0.71 | 2.2 | 0.03 | 0.08-1.35 |

| Psychological support over the follow-up period | 1.46 | 1.44 | 0.15 | -0.54-3.46 |

| F=5.62, p<0.01; r2=0.19, n=250 | ||||

| GHQ-Total score | ||||

| Hours of TV viewing (follow-up period) | 1.61 | 1.43 | 0.15 | -0.61-3.83 |

| Other drugs use (follow-up period) | 4.52 | 1.65 | 0.11 | -0.89-9.94 |

| Perceived risk level to be infected (follow-up period) | 4.78 | 3.01 | <0.01 | 1.65-7.89 |

| Well-defined action protocol (follow-up period) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.97 | -1.76-1.83 |

| Receive conflicting information (follow-up period) | 1.37 | 1.42 | 0.16 | -0.53-3.28 |

| Deceased patient assigned to your care (follow-up period) | 2.03 | 1.2 | 0.23 | -1.31-5.37 |

| Working more hours (follow-up period) | 2.13 | 1.26 | 0.21 | -1.20-5.46 |

| Redeployed (follow-up period) | 1.22 | 0.7 | 0.49 | -2.23-4.67 |

| Leaving home for fear of spreading it to my family (follow-up period) | 2.88 | 0.85 | 0.41 | -3.81-9.58 |

| Overwhelmed by work (follow-up period) | 5.99 | 5.92 | <0.001 | 4.01-7.99 |

| Psychological support over the follow-up period | 5.53 | 1.76 | 0.08 | -0.67-11.73 |

| F=11.45, p<0.01; r2=0.35, n=250 | ||||

| Suicidal thoughts | ||||

| History of mental health diagnosis | -0.19 | -2.2 | 0.03 | -0.35-(-0.01) |

| Hours of TV viewing (follow-up period) | 0.09 | 1.92 | 0.06 | -0.01-0.18 |

| Other drugs use (follow-up period) | 0.39 | 3.46 | <0.01 | 0.17-0.60 |

| Leaving home for fear of spreading it to my family (follow-up period) | 0.34 | 2.32 | 0.02 | 0.05-0.63 |

| F=7.21, p<0.01; r2=0.11, n=250 |

GHQ-28: General Health Questionnaire; PPE: Personal Protective Equipment.

The main findings derived from our study were: (i) a progressive worsening in the GHQ-somatic subscale in the total sample of HCW, (ii) significant gender differences in general health but not in suicidal thoughts, (iii) women and men were characterized by a different pattern of evolution in somatic, anxiety and insomnia dimensions, and iv) different psychological wellbeing dimensions are predicted by a singular set of variables although risk perception of COVID-19 infection and overwhelmed feeling at work seem to play an important role when psychological distress is considered globally.

The most common physical consequences reported by HCW derived from the response to the pandemic were headache and fatigue.28 These two core psychical symptoms are particularly represented in the somatic dimension which composed the first GHQ-28 dimension.25 In that sense, one of the main reasons which could explain our results may be that fatigue represents one of the main indicators of burn-out. Fatigue has been independently related to work overload, frequent overtime hours and too little vacation or leisure time.29 These fatigue risk factors have been extended reported by HCW since the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic.30 On the other hand, headache has been related not only with work conditions but also to the use of the personal protective equipment.31

Previous studies have suggested significant gender differences in emotional reactive responses to the pandemic.32 In congruence with this, we have found significant gender differences in all GHQ-28 dimensions as well as in the total score of the mentioned questionnaire. Moreover, post hoc analyses revealed significant differences between men and women over the follow up period in two specific dimensions (somatic and anxiety) as well as in the total score of GHQ-28. In particular, we observed that women were characterized by a greater response at baseline, but men showed an increase in emotional responses during the observation period. In line with our results, a recent 14-month follow-up study reported that males presented worsening in insomnia symptoms and increased posttraumatic stress symptoms over the follow-up studied. It is worth mentioning that Rossi et al. (2021) did not report that female gender was related to worsening in any of the outcomes considered by the authors.33

One of the possible potential explanations for these gender differences is that women are characterized by the use of “tend-and-befriend” (i.e., response to threat based on protection of offspring (tend) and seeking out their social group for mutual defence (befriend)) as a mechanism to cope with stress situations.34,35 Coping strategies have been analyzed as an attempt to explain these differences between genders. It has been identified that men tend to use strategies based on problem solving, while women are more likely to seek some social support and use emotional coping strategies.9,36 Furthermore, it is discussed that women seem to be more vulnerable than men on the first moment of a stressful life event, being at major risk of suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression symptoms, but also a wider capacity to use adaptive coping strategies as mentioned above,9 which could favour their recovery from these symptoms. It has been suggested that tend-and-befriend copy strategy may depends at least in part on oxytocin, oestrogen, and endogenous opioid mechanism, among other neuroendocrine underpinnings. In particular, Taylor et al. (2000) hypothesized that sympathetic and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical responses to stress could be underregulated by oxytocin under stressful circumstances. Precisely, the interaction between endogenous opioid mechanism, sex-linked hormones and oxytocin may foster affiliative behaviour in response to stress.34

Another important consequence of the COVID-19 on the mental health status of the HCW is the possible increasing of suicidality among this population.37 A study which investigated 30-days prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours and associated risk factors in HCW during the first wave, reported that 1.5% of the HCW who participated in their study informed of the presence of suicidal ideation.38 In the present study the average score in the item employed to evaluate suicidal thoughts was 0.13±0.51 in May 2020 and 0.12±0.45 in November 2020. Thus, our results indicate a low prevalence of suicidal thoughts among our participants. One possible reason for these results is that according to official data, the months with highest number of newly COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths due to COVID-19 in Andalusia (almost 50% of our participants work in the public health system of Andalusia) occurred from November onwards.39 It is possible that the increasing clinical demand supported by these professionals after November 2020 could have an impact on suicidal ideation, which should be the subject of further investigations.

Substance use was the main predictor of suicidal thoughts among our sample. It has been reported that substance abuse is more prevalent among HCW than in general population and it has been suggested that drug misuse could be closely related to suicidal ideation among HCW over COVID-19 pandemic.40,41 An unexpected result was that those without history of mental health diagnosis presented higher risk of suicidal ideation. This result could be explained by the possibility that those with a mental health diagnosis may have been in contact with mental health professionals or that attending therapeutic interventions may have had positive long-term effects. This is a speculative reasoning and further investigations are required.

Perceived risk to be infected and overwhelmed feelings at work over the follow-up periods resulted the main predictors of psychological distress understood globally. These results are in line with previous studies which underlines that the risk to be infected as well as work burnout represent some of the main predictors of bad outcomes in mental and physical health among HCW facing COVID-19.42 On the other hand, we could observe that each GHQ-28 dimension as well as the items used to measure suicidal thoughts are predicted by a particular set of variables. This underscores the complex network of factors involved in the psychological well-being of workers facing a major disaster.

Institutions must address the psychological, social, occupational, and other needs directly related to the event to reduce as much as possible the consequences that facing with major disasters could have on the mental health status of the workers.43 Regarding this, Staff Support Centres resulted the most used service by HCW facing COVID-19 in an investigation carried out in United States which could be understood as the interventions that best suit the needs of the HCW facing major disasters.44 On the other hand, Priede et al. (2021) described that several hospitals in Spain developed mental health interventions for HCW, with interventions focused on emotion regulation as the main intervention.45

Social stigma against HCW has been identified as a potential predictor of bad mental health status in this population.46 In our study this potential predictor was included in the analyses, but regression analyses models fail to identify discrimination against HCW as a significant predictor of suicidality or the mental health outcomes. Previous studies carried out in Spain reported that a considerable proportion of HCW felt stigmatized and/or discriminated and that discrimination was related to depression, psychological distress and with increase in risk of death thoughts.21 One of the main reasons for the divergent results between the studies may be due to the differences in the design. It could be possible that discrimination effects on mental health status are lessened over time or even that discrimination or stigma has been reduced over time.

One of the main strengths of the study was the inclusion of a comprehensive set of sociodemographic, psychological, occupational, and social variables as well as COVID-19 related factors. On the other hand, some limitations should be considered such as the attrition suffered during follow-up period. The study also presents limitations inherent to online survey studies such as possible bias in the respondent's answers. In addition, more sophisticated methodology such as growth mixture modelling analyses should be used to explore potential different trajectories as well as predictors of worsening trajectories. Unfortunately, we were unable to carried out these analyses due to the lack of a third monitoring period. In addition, not all the different regions of the Spanish state are equally represented. Finally, most of the variables included in the study were evaluated throughout a proforma. The use of validated questionnaires could improve the quality of the data, but the extension of the survey prevented the inclusion of validated scales.

The present outcomes shed light on the relevance of the somatic reactions as they are the most affected dimension over the follow-up period among HCW, highlighting the need of assessing the caregivers’ well-being, especially during stressful situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, gender differences were observed throughout the follow-up period in relation to symptomatic evolution: women tend to show greater psychological distress at first, but these differences tend to disappear over time. Finally, a particular complex set of psychological, sociodemographic, occupational and factors related to COVID-19 seem to predict different dimensions of psychological well-being of the HCW. The application of adequate mental health assessment and healthy lifestyle habits advisement in HCW may be a suitable preventive intervention to improve stressful life events reactions and to reduce somatic symptoms in this population. In addition, the improvement of working conditions could have important repercussion on the HCW mental health status.

Authors’ contributionsMCR: Study conception, design, processing data, analysis, drafting and manuscript revision. CMG: Drafting and manuscript revision. NGT: Manuscript revision. AMM: Manuscript revision. PRP: Manuscript revision. MRV: Study conception, design and manuscript revision. BCF: Study conception, design and manuscript revision. All authors have made substantial contributions and have approved of the final version of the manuscript.

Role of funding sourceThis study was not funded.

MCR works as Clinical Psychologist at Virgen del Rocío University Hospital (Seville, Spain) via Consejería de Salud y Familias (Junta de Andalucía) 2020 grant which covers his salary (RH-0081-2020).

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the Health Care Workers for participating in this study. We would like to thank Unidad de Gestión Clinical Salud Mental Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío for their contribution to data acquisition and administration. We would also like to thank to Ana Rubio-García, Laura Armesto-Luque and Gonzalo Rodriguez-Menendez for the acquisition of the data.