Controversy exists regarding the DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Given the mixed results that have been reported, our main aim was to determine DSM-5 sensitivity and specificity in a child and adolescent Spanish sample. As secondary goals, we assessed the diagnostic stability of DSM-IV-TR in DSM-5, and clinical differences between children diagnosed with an ASD or a social (pragmatic) communication disorder (SPCD).

MethodsThis study was carried out in 2017, reviewing the medical records of patients evaluated in our service. Items from a parent report measure of ASD symptoms (Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised) were matched to DSM-5 criteria and used to assess the sensitivity and specificity of the DSM-5 criteria and current DSM-IV criteria when compared with clinical diagnoses.

ResultsDSM-5 sensitivity ranged from .69 to 1.00, and was higher in females. By age, the DSM-5 and DSM-IV-TR criteria showed similar sensitivity. In the case of intellectual quotient, DSM-5 criteria sensitivity was lower for those in the “low-functioning” category. DSM-5 specificity ranged from .64 to .73, while DSM-5 specificity was similar for all phenotypic subgroups. With respect to stability, 83.3% of autism disorder cases retained a diagnosis of ASD using the DSM-5 criteria. With regard to differences between ASD and SPCD, we found that patients diagnosed with ASD received more pharmacological treatment than those diagnosed with SPCD.

ConclusionsFurther research is required to confirm our results. Studies focusing on the SPCD phenotype will be necessary to determine outcome differences with ASD and the most effective diagnostic and therapeutic tools.

Existe controversia acerca de los criterios DSM-5 para el diagnóstico de los trastornos del espectro autista (TEA). En la literatura encontramos resultados discrepantes, siendo el objetivo del estudio determinar la sensibilidad y la especificidad de los criterios DSM-5 para TEA en niños y adolescentes españoles. También se determinará la estabilidad del diagnóstico al pasar del DSM-IV-TR al DSM-5 y las diferencias clínicas entre TEA y trastorno de la comunicación social (TCS).

Material y métodosEl estudio se llevó a cabo en 2017, revisando las historias clínicas de los pacientes evaluados en nuestro servicio. Los ítems de la entrevista diagnóstica para el autismo (Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised) se ajustaron al DSM-5 y se utilizaron para evaluar la sensibilidad y la especificidad de dicho manual.

ResultadosLa sensibilidad del DSM-5 fue de 0,69-1,00, mayor para el género femenino, sin diferencias con respecto a la edad y menor para los pacientes con bajo funcionamiento. La especificidad fue de 0,64-0,73. Respecto a la estabilidad, el 83,3% de los casos de autismo diagnosticados con el DSM-IV-TR mantuvieron el diagnóstico siguiendo los criterios del DSM-5. En cuanto a las diferencias entre los pacientes diagnosticados de TEA y los diagnosticados de TCS, cabe mencionar que los primeros requirieron más tratamientos farmacológicos durante su evolución.

ConclusionesSe necesitan más estudios centrados en el diagnóstico de TCS para determinar si la evolución es diferente a la de los pacientes diagnosticados de TEA. También será necesario confeccionar nuevas herramientas diagnósticas y terapéuticas para los pacientes con diagnóstico de TCS.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-IV-TR)1 placed autism, Asperger's disorder (AD), and pervasive developmental disorders – not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) under the classification of pervasive developmental disorders (PDD). It was proposed that DSM-52 should replace the term PDD with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In DSM-IV-TR autism was characterised by a triad of symptoms, including the presence of persistent deficits in social communication, deficits in social interaction in various contexts, and restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities.3 It was changed to 2 categories in DSM-5, integrating deficits in social communication and social interaction on the one hand, and restricted patterns of interest and stereotyped behaviours on the other. Sensory interests were also added as a diagnostic criterion and the age at onset criteria of under 3 years was relaxed to early childhood.2

One of the main concerns of mental health professionals regarding the new DSM-5 criteria was that patients who had previously been diagnosed with AD or PDD-NOS were excluded.4–6

A further addition to DSM-5 was the inclusion of the diagnosis of social (pragmatic) communication disorder (SPCD). This diagnosis is included under Communication Disorders in the Neurodevelopmental Disorders section. In SPCD there is a deficit in communication and in social interaction. It differs from AD in that restricted interests or repetitive behaviours are not present.2 Although the SPCD category may include individuals who previously met DSM-IV-TR criteria for PDD-NOS, the aim of this new category is to provide a clear definition for those disorders that were previously incompletely defined.7 However, this new diagnosis is problematic given its disputed scientific basis.8

Several studies have evaluated the psychometric properties of the DSM-5, with mixed results. Thus far, it appears that the DSM-5 is psychometrically superior to the DSM-IV-TR, even adjusting for gender and IQ.9 All studies to date have included children and adolescents previously diagnosed with PDD.

In terms of sensitivity, using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) as external validation measures, Huerta et al. found higher sensitivity for DSM-5, even for groups more difficult to detect (very young children, female gender, or denoted as higher cognitively functioning).10 However, other studies found DSM-5 to have lower sensitivity in the diagnosis of ASD.4,11,12 For example, Gibbs et al. found that a greater number of symptoms are needed to make a diagnosis of ASD with the new criteria.11 In another study, Mattila et al. also found that the new criteria were less sensitive in identifying individuals with ASD, especially for high-functioning individuals with a previous diagnosis of AD.12 Similar results to those of Mattila et al. were found by McPartland et al. who concluded that specificity improved with the new criteria, but at the expense of poorer sensitivity.4 When we examined the sensitivity of the new criteria according to age, we found a study by Barton et al. that concluded that DSM-5 would identify younger subjects better, making it possible to bring forward the age of therapeutic intervention.13 Another study by Christiansz et al. in 2016 also found high sensitivity for the new criteria in younger subjects.14

We also found that the different studies diverged in terms of specificity: while some found increased specificity with the new criteria (especially studies that consider ADI-R and ADOS scores),4,10,15 others concluded that the DSM-5 excludes patients with higher cognitive functioning,4,12 younger children,13,14 and those fulfilling DSM-IV-TR criteria for AD or PDD-NOS.4,11

Most of the published studies were conducted in the USA,4,9,10,13,14 except for one conducted in Australia,11 and another in Finland.12

In view of the variability of the results found in the scientific literature, the main objective of our study was to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the DSM-5 criteria in a sample of children and adolescents, based on the symptoms scored by parents in the ADI-R, replicating the 2012 study by Huerta et al.10 We also examined whether there were differences in sensitivity and specificity according to gender, age, or IQ. As secondary objectives, we assessed the diagnostic stability of DSM-5 compared to DSM-IV-TR and the clinical differences between children diagnosed with ASD or SCPD according to the new DSM-5 criteria.

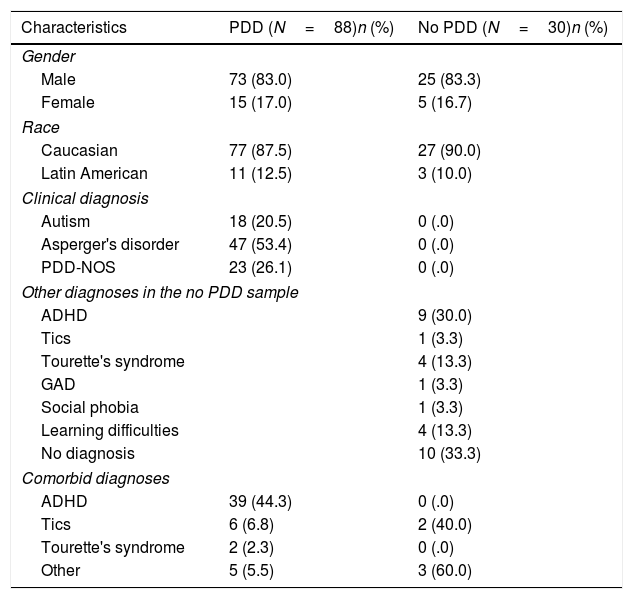

Material and methodsParticipantsThe present study was conducted in the child and adolescent psychiatry and psychology department of a Spanish hospital in 2017. We reviewed the medical records of all patients assessed in this department. Most of the selected patients came from the child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinics or from the day hospital. The demographic data are listed in Table 1. The 118 patients included were predominantly Caucasian and male. Of the 118 subjects with a high suspicion of PDD, 88 had been finally diagnosed with PDD and 30 with no PDD according to DSM-IV-TR criteria, and after the ADI-R16 diagnostic interview was performed by a PDD specialist clinician. AD was the most frequent diagnosis. Of the subjects, 59.1% with a diagnosis of PDD had a comorbid diagnosis, as described in Table 1. In those that were no PDD, 76.6% of the sample had another diagnosis. The participants ranged in age from 4 to 17 years and 11 months. Prior to applying the ADI-R, screening instruments such as the Social Communication Questionnaire,17 Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire,18 and the Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test19 were administered.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample with a diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder according to DSM-IV-TR.

| Characteristics | PDD (N=88)n (%) | No PDD (N=30)n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 73 (83.0) | 25 (83.3) |

| Female | 15 (17.0) | 5 (16.7) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 77 (87.5) | 27 (90.0) |

| Latin American | 11 (12.5) | 3 (10.0) |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||

| Autism | 18 (20.5) | 0 (.0) |

| Asperger's disorder | 47 (53.4) | 0 (.0) |

| PDD-NOS | 23 (26.1) | 0 (.0) |

| Other diagnoses in the no PDD sample | ||

| ADHD | 9 (30.0) | |

| Tics | 1 (3.3) | |

| Tourette's syndrome | 4 (13.3) | |

| GAD | 1 (3.3) | |

| Social phobia | 1 (3.3) | |

| Learning difficulties | 4 (13.3) | |

| No diagnosis | 10 (33.3) | |

| Comorbid diagnoses | ||

| ADHD | 39 (44.3) | 0 (.0) |

| Tics | 6 (6.8) | 2 (40.0) |

| Tourette's syndrome | 2 (2.3) | 0 (.0) |

| Other | 5 (5.5) | 3 (60.0) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 10.44 (3.13) | 11.04 (3.57) |

| Socioeconomic status | 49.68 (15.59) | 53.11 (15.69) |

| Verbal understanding | 102.73 (19.17) | 101.32 (13.34) |

| IQ | 100.17 (19.44) | 95.00 (13.89) |

| SCQ | 13.83 (6.08) | 12.63 (5.22) |

| ASSQ | 21.20 (9.22) | 17.20 (8.38) |

| CAST | 14.00 (4.85) | 12.82 (4.74) |

ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; ASSQ: Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire; CAST: Childhood Autism Spectrum Test; GAD: Generalised Anxiety Disorder; IQ: Intelligence Quotient; PDD: Pervasive Developmental Disorder; PDD-NOS: Pervasive Developmental Disorder – not otherwise specified; SCQ: Social Communication Questionnaire; SD: Standard Deviation.

The ethics committee approved all procedures. This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2000).

Other assessmentsComorbid diagnoses: these were assessed by the psychiatrist or psychologist using a diagnostic interview based on DSM-IV-TR.1

Socioeconomic status: this was estimated using the Hollingshead–Redlich scale,20 administered by the interviewing psychiatrist.

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV21: this was used to obtain the verbal comprehension index and IQ.

The inclusion criteria were age between 4 and 17 years and ADI-R assessed. Patients with an incomplete ADI-R were excluded. The final sample comprised 118 patients. To assess differences between children diagnosed with ASD or SPCD according to DSM-5, data were collected on the patients’ status (linkage to mental health services, under psychotropic drug treatment, performance at school and having friends) in 2017.

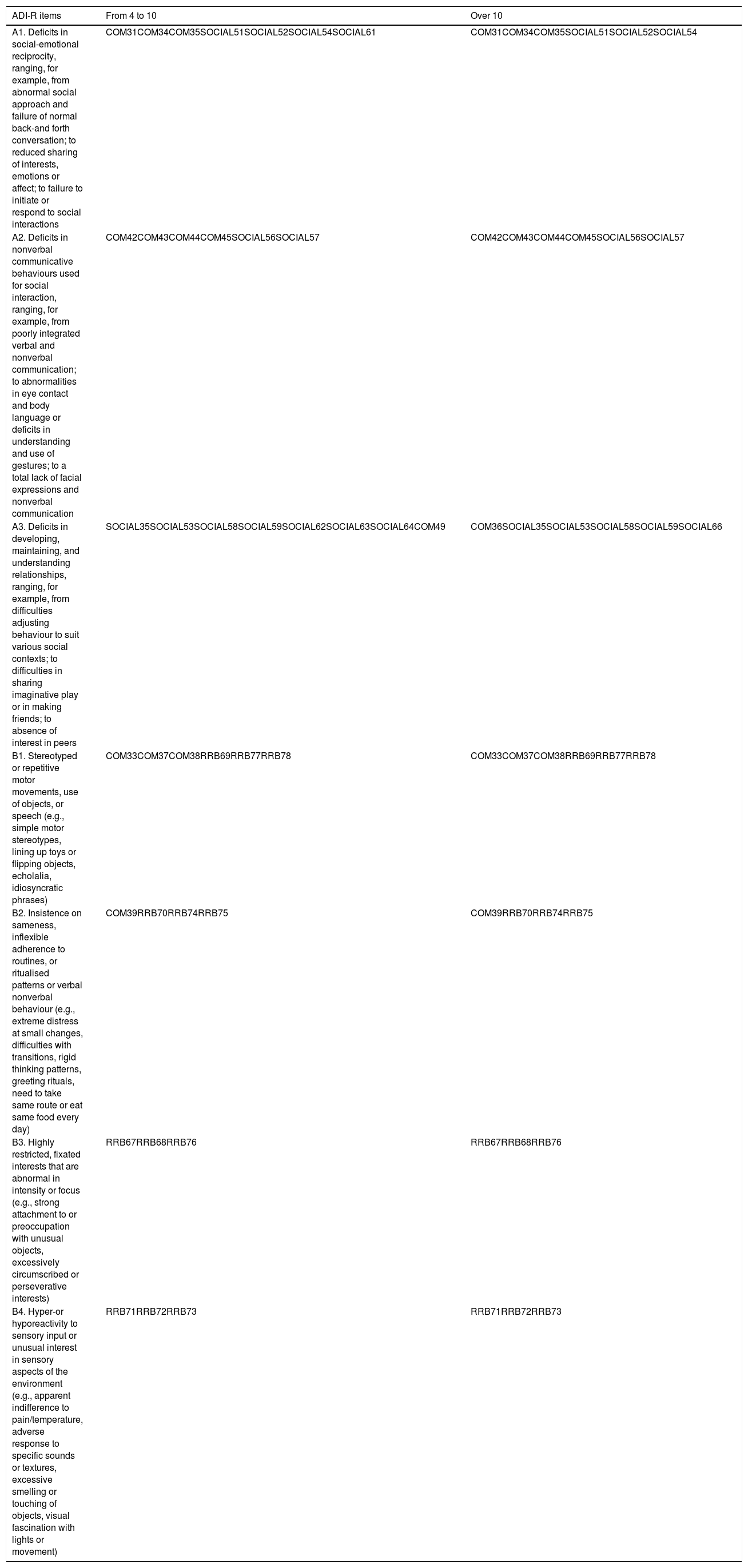

Working with the DSM criteriaThe diagnostic measures used in the present study included individual items from the Spanish version of the ADI-R.16 This is a standardised, semi-structured clinical diagnostic instrument for assessing autism in children and adults based on information provided by caregivers. It provides a diagnostic algorithm for autism, as described in both the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases and the DSM. The interview contains 93 items and focuses on behaviours in 3 content areas or domains: qualities of social interaction, communication and language, and repetitive, restricted, and stereotyped interests and behaviours. The ADI-R interview generates scores in each of the 3 content areas. High scores indicate problematic behaviour in a particular domain. Scores are based on the clinician's judgement following the caregiver's report of the child's behaviour and development. For each item, the clinician awards a score ranging from 0 (“behaviour not present”) to 3 (“extreme severity”). Autism is classified when scores in the 3 content areas of communication, social interaction and behaviour patterns meet or exceed the specified cut-offs and the onset of the disorder is evident by the age of 36 months.

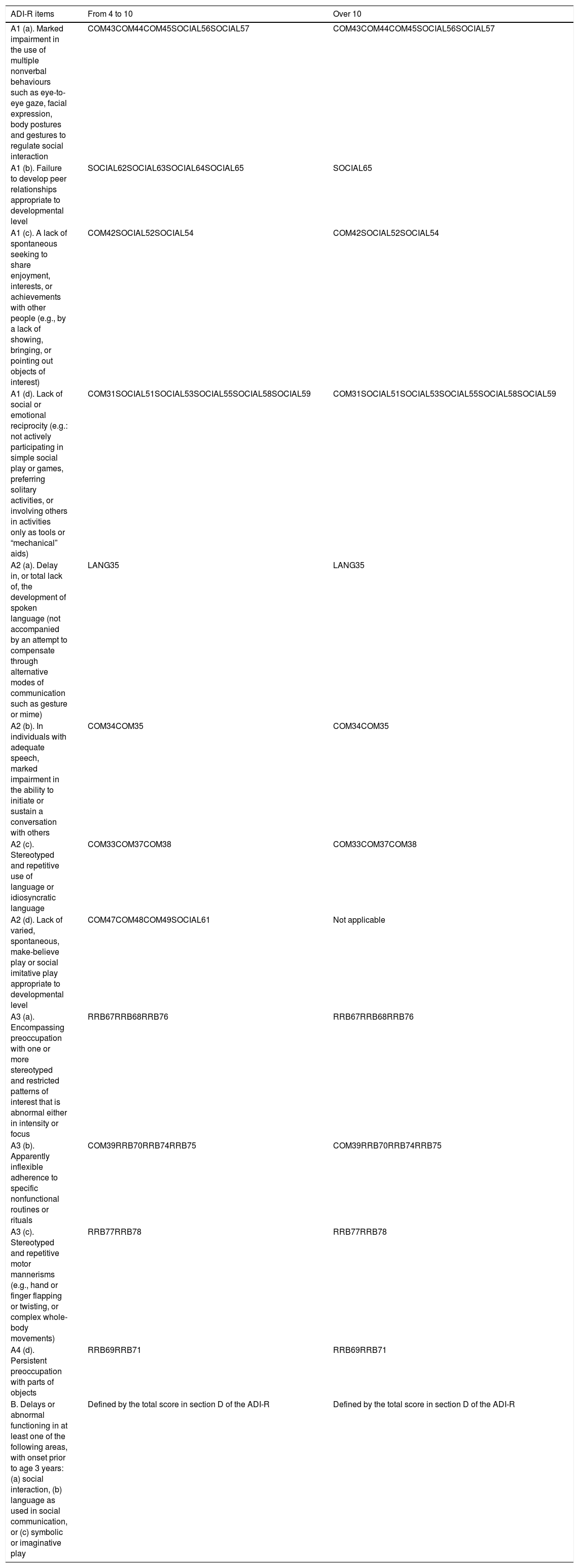

To begin our analyses, the ADI-R items were mapped onto the DSM-5 criteria, replicating the method used in the study by Huerta et al.10 (the item assignments are available in Tables 2 and 3). Before assigning items to each criterion, the subjects were divided according to age. Two groups were created: one for children aged 4–10 years and one for children over the age of 10 years. For each item included in the DSM-IV and DSM-5 item maps, a score of 1, 2 or 3 indicated the presence of a symptom, while a score of 0 indicated the absence of symptoms. DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 guidelines were then used to determine whether or not each participant met the DSM-5 criteria for ASD and DSM-IV-TR criteria for ASD, AD or PDD-NOS.

Items from the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised applying DSM-5 criteria.

| ADI-R items | From 4 to 10 | Over 10 |

|---|---|---|

| A1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions | COM31COM34COM35SOCIAL51SOCIAL52SOCIAL54SOCIAL61 | COM31COM34COM35SOCIAL51SOCIAL52SOCIAL54 |

| A2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviours used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication | COM42COM43COM44COM45SOCIAL56SOCIAL57 | COM42COM43COM44COM45SOCIAL56SOCIAL57 |

| A3. Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behaviour to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers | SOCIAL35SOCIAL53SOCIAL58SOCIAL59SOCIAL62SOCIAL63SOCIAL64COM49 | COM36SOCIAL35SOCIAL53SOCIAL58SOCIAL59SOCIAL66 |

| B1. Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypes, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases) | COM33COM37COM38RRB69RRB77RRB78 | COM33COM37COM38RRB69RRB77RRB78 |

| B2. Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualised patterns or verbal nonverbal behaviour (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat same food every day) | COM39RRB70RRB74RRB75 | COM39RRB70RRB74RRB75 |

| B3. Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g., strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests) | RRB67RRB68RRB76 | RRB67RRB68RRB76 |

| B4. Hyper-or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement) | RRB71RRB72RRB73 | RRB71RRB72RRB73 |

Source: Huerta et al.

Items from the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised applying DSM-IV-TR criteria.

| ADI-R items | From 4 to 10 | Over 10 |

|---|---|---|

| A1 (a). Marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviours such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures and gestures to regulate social interaction | COM43COM44COM45SOCIAL56SOCIAL57 | COM43COM44COM45SOCIAL56SOCIAL57 |

| A1 (b). Failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level | SOCIAL62SOCIAL63SOCIAL64SOCIAL65 | SOCIAL65 |

| A1 (c). A lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people (e.g., by a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest) | COM42SOCIAL52SOCIAL54 | COM42SOCIAL52SOCIAL54 |

| A1 (d). Lack of social or emotional reciprocity (e.g.: not actively participating in simple social play or games, preferring solitary activities, or involving others in activities only as tools or “mechanical” aids) | COM31SOCIAL51SOCIAL53SOCIAL55SOCIAL58SOCIAL59 | COM31SOCIAL51SOCIAL53SOCIAL55SOCIAL58SOCIAL59 |

| A2 (a). Delay in, or total lack of, the development of spoken language (not accompanied by an attempt to compensate through alternative modes of communication such as gesture or mime) | LANG35 | LANG35 |

| A2 (b). In individuals with adequate speech, marked impairment in the ability to initiate or sustain a conversation with others | COM34COM35 | COM34COM35 |

| A2 (c). Stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language | COM33COM37COM38 | COM33COM37COM38 |

| A2 (d). Lack of varied, spontaneous, make-believe play or social imitative play appropriate to developmental level | COM47COM48COM49SOCIAL61 | Not applicable |

| A3 (a). Encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus | RRB67RRB68RRB76 | RRB67RRB68RRB76 |

| A3 (b). Apparently inflexible adherence to specific nonfunctional routines or rituals | COM39RRB70RRB74RRB75 | COM39RRB70RRB74RRB75 |

| A3 (c). Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand or finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements) | RRB77RRB78 | RRB77RRB78 |

| A4 (d). Persistent preoccupation with parts of objects | RRB69RRB71 | RRB69RRB71 |

| B. Delays or abnormal functioning in at least one of the following areas, with onset prior to age 3 years: (a) social interaction, (b) language as used in social communication, or (c) symbolic or imaginative play | Defined by the total score in section D of the ADI-R | Defined by the total score in section D of the ADI-R |

Source: Huerta et al.

SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, USA) was used for the data analysis. An analysis was conducted to examine the sensitivity and specificity of the DSM-5 criteria for ASD and the DSM-IV criteria for PDD in the study sample. We then assessed sensitivity and specificity in specific subgroups according to gender, age, and IQ. McNemar's test was used to assess whether there were differences in the classification of no PDD between DSM-5 and DSM-IV-TR. The χ2 and Student's t-test were used to study differences between ASD and SPCD. The level of statistical significance was set at p<.05.

ResultsTable 1 shows the demographic data. There were no significant differences between the PDD and the no PDD groups in socioeconomic status or IQ. Although the PDD group's scores on the screening questionnaires were higher, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups.

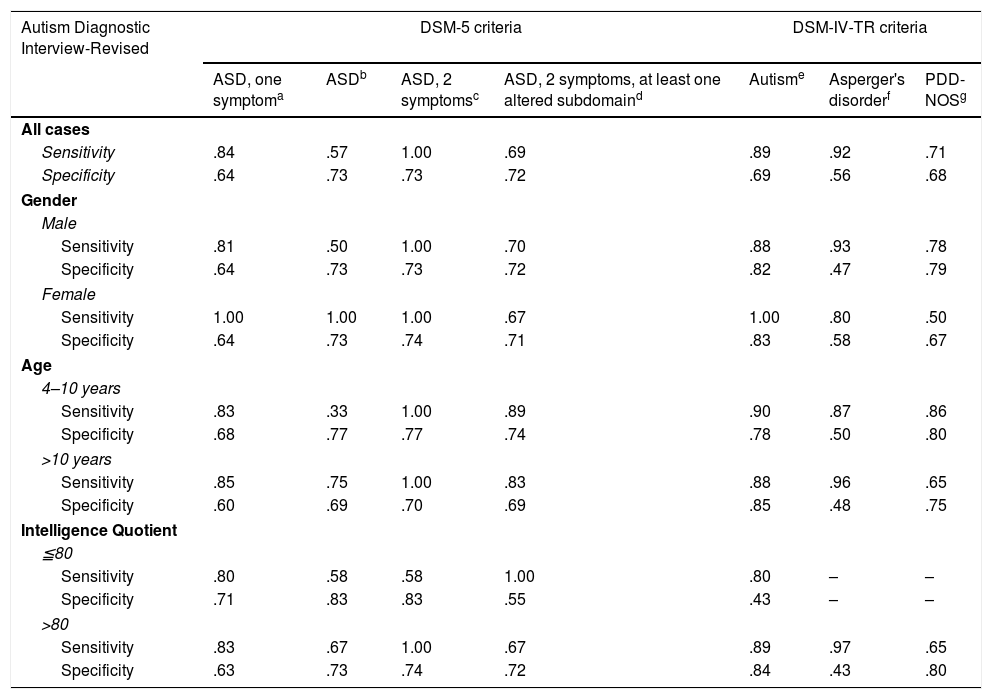

Sensitivity and specificity of the DSM-5 criteria for ASD and DMS-IV-TR for PDDThe DSM-5 and DSM-IV-TR classifications were based on the information from the ADI-R. As Table 4 shows, the sensitivity of DSM-5 ranged from .69 to 1.00, except for the ASD column (.57) due to the small sample size (N=7). The sensitivity of DSM-IV-TR ranged from .71 to .92. Overall, the sensitivity scores of the DSM-5 and DSM-IV-TR criteria were similar. If we analyse the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic groups, we obtain lower sensitivity for the PDD-NOS group. We also examined sensitivity within the phenotypic PDD subgroups according to gender, age, and IQ. As shown in Table 2, sensitivity in females was higher with the DSM-5 criteria. By age, if we exclude the ASD group, the results are similar with the DSM-5 and DSM-IV-TR criteria. In the case of IQ, for those who were “low functioning”, sensitivity was lower with the DSM-5 criteria.

Sensitivity and specificity of DSM-5 criteria for ASD and the DSM-IV criteria for PDD, in patients diagnosed with PDD according to DSM-IV.

| Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised | DSM-5 criteria | DSM-IV-TR criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD, one symptoma | ASDb | ASD, 2 symptomsc | ASD, 2 symptoms, at least one altered subdomaind | Autisme | Asperger's disorderf | PDD-NOSg | |

| All cases | |||||||

| Sensitivity | .84 | .57 | 1.00 | .69 | .89 | .92 | .71 |

| Specificity | .64 | .73 | .73 | .72 | .69 | .56 | .68 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | |||||||

| Sensitivity | .81 | .50 | 1.00 | .70 | .88 | .93 | .78 |

| Specificity | .64 | .73 | .73 | .72 | .82 | .47 | .79 |

| Female | |||||||

| Sensitivity | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .67 | 1.00 | .80 | .50 |

| Specificity | .64 | .73 | .74 | .71 | .83 | .58 | .67 |

| Age | |||||||

| 4–10 years | |||||||

| Sensitivity | .83 | .33 | 1.00 | .89 | .90 | .87 | .86 |

| Specificity | .68 | .77 | .77 | .74 | .78 | .50 | .80 |

| >10 years | |||||||

| Sensitivity | .85 | .75 | 1.00 | .83 | .88 | .96 | .65 |

| Specificity | .60 | .69 | .70 | .69 | .85 | .48 | .75 |

| Intelligence Quotient | |||||||

| ≦80 | |||||||

| Sensitivity | .80 | .58 | .58 | 1.00 | .80 | – | – |

| Specificity | .71 | .83 | .83 | .55 | .43 | – | – |

| >80 | |||||||

| Sensitivity | .83 | .67 | 1.00 | .67 | .89 | .97 | .65 |

| Specificity | .63 | .73 | .74 | .72 | .84 | .43 | .80 |

ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; PDD-NOS: Pervasive Developmental Disorder – not otherwise specified.

At least one symptom in subdomains A1 and A2, at least one symptom to some extent from A3, and at least one symptom to some extent from 2 or more subdomains B.

At least 2 symptoms from each subdomain A and at least 2 symptoms from one or more subdomains B; or at least 2 symptoms from 2 or more subdomains A and at least 2 symptoms from 2 or more subdomains B.

At least one symptom from 2 or more subdomains A, at least one symptom from subdomain B, at least one symptom from subdomain C and at least 6 symptoms in A, B or C according to the parents.

At least one symptom in 2 or more subdomains A and at least one symptom in one or more subdomains C.

At least one symptom in 2 or more subdomains A and at least one symptom in one or more subdomains B or C (Tables 2 and 3: Huerta et al.10).

Table 4 shows the specificity scores. With the DSM-5 criteria, specificity ranged from .64 to .73. In all cases, the specificity of DSM-IV-TR was .69 for autistic disorder, .56 for AD and .68 for PDD-NOS. The specificity of DSM-5 was similar for all phenotypic subgroups. The specificity of DSM-IV-TR was lower for AD in all phenotypic subgroups with DSM-IV-TR criteria.

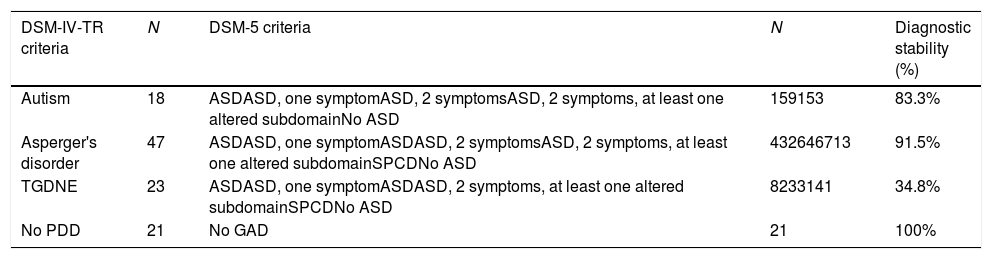

Stability of diagnosesTable 5 provides information on the stability of diagnoses. With respect to autism, 83.3% of the sample maintained the diagnosis of ASD with DSM-5 criteria. The DSM-5 misclassified 3 patients because they did not present enough symptoms in social communication or in the domain of restricted and repetitive behaviour (χ2=5.748; df=1; p<.001). For AD, 91.5% of the sample met criteria for ASD according to DSM-5. One patient was diagnosed with SPCD, and 3 patients were misclassified following DSM-5 criteria because they did not exhibit sufficient symptoms in social communication or in the domain of restricted and repetitive behaviour (χ2=36.681; df=1; p<.001). In the case of PDD-NOS, only 34.8% maintained the diagnosis of ASD. Sixty point nine percent of the PDD-NOS diagnosis changed to SPCD (χ2=4.989; df=1; p<.001), and one patient was misclassified because they did not exhibit sufficient symptoms in the social communication section or in a restricted and repetitive behaviour domain.

Diagnostic stability with DSM-5 criteria.

| DSM-IV-TR criteria | N | DSM-5 criteria | N | Diagnostic stability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autism | 18 | ASDASD, one symptomASD, 2 symptomsASD, 2 symptoms, at least one altered subdomainNo ASD | 159153 | 83.3% |

| Asperger's disorder | 47 | ASDASD, one symptomASDASD, 2 symptomsASD, 2 symptoms, at least one altered subdomainSPCDNo ASD | 432646713 | 91.5% |

| TGDNE | 23 | ASDASD, one symptomASDASD, 2 symptoms, at least one altered subdomainSPCDNo ASD | 8233141 | 34.8% |

| No PDD | 21 | No GAD | 21 | 100% |

ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; GAD: Generalised Anxiety Disorder; PDD-NOS: Pervasive Developmental Disorder – not otherwise specified; SPCD: Social (pragmatic) Communication Disorder.

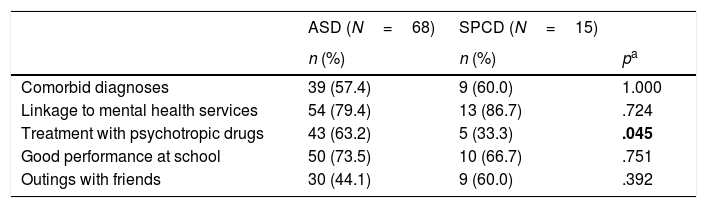

Table 6 shows the demographic and clinical differences between patients diagnosed with ASD and SPCD. Statistically significant differences in pharmacological treatment were found between the 2 groups (p=.045). In patients with ASD, 63.2% of the sample was under pharmacological treatment (53.5% with stimulants, 11.6% with stimulants and antipsychotics, and 34.9% with other combinations). In the case of SPCD, only 5 out of 15 patients (33.3) were under treatment with psychotropic drugs (60% with stimulants, 20% with stimulants and antipsychotics, and 20% with antidepressants). No differences were found in the scores of the screening questionnaires between the two groups. Total IQ was significantly higher and processing speed scores were higher in the SPCD group.

Differences between children diagnosed with ASD or SPCD according to DSM-5.

| ASD (N=68) | SPCD (N=15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | pa | |

| Comorbid diagnoses | 39 (57.4) | 9 (60.0) | 1.000 |

| Linkage to mental health services | 54 (79.4) | 13 (86.7) | .724 |

| Treatment with psychotropic drugs | 43 (63.2) | 5 (33.3) | .045 |

| Good performance at school | 50 (73.5) | 10 (66.7) | .751 |

| Outings with friends | 30 (44.1) | 9 (60.0) | .392 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | pb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCQ | 14.2 (6.6) | 12.5 (5.4) | .390 |

| ASSQ | 20.9 (8.6) | 18.4 (4.8) | .274 |

| Intelligence Quotient | 100.5 (18.6) | 112.3 (11.2) | .039 |

| Processing speed | 95.8 (14.4) | 111.1 (10.7) | .008 |

ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; ASSQ: Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire; SCD: Social Communication Disorder; SCQ: Social Communication Questionnaire; SD: Standard Deviation.

The present study examined the sensitivity and specificity of the DSM-5 criteria in a Spanish sample of children and adolescents according to the item scores in the ADI-R. The DSM-5 criteria demonstrated adequate sensitivity, indicating that the new criteria correctly classified a wide range of children with ASD in accordance with some previous studies.10,22 High sensitivity was also found when classifying by gender, age and IQ, as previously shown by Huerta et al.10 As expected, the sensitivity of the DSM-5 criteria was higher for children who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for autism disorder and lower for those who met criteria for PDD-NOS. In terms of specificity, our results showed that specificity was slightly better with the DSM-5 criteria than with the DSM-IV-TR criteria, as had also been shown by Mazurek et al.22 Mattila et al. also concluded that moving from 3 to 2 categories improved diagnostic sensitivity and specificity ranges.12 However, other reviewed studies found that the DSM-5 criteria for ASD have lower sensitivity but higher specificity compared to DSM-IV-TR,4,11,23 or higher sensitivity with lower ranges of specificity ranges.14 A possible explanation for our positive results could be that we used screening tools (Childhood Autism Spectrum Questionnaire, Social Communication Questionnaire, Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire) in patients with a high likelihood of ASD, prior to the diagnostic assessment using the ADI-R.

Regarding diagnostic stability, 75% of the sample diagnosed with autism disorder, AD or PDD-NOS by DSM-IV-TR would maintain their diagnosis under the new DSM-5 criteria. We found similar results in 2 previous studies.24,25 However, 25% of the sample was misclassified, and therefore it is possible that these criteria are too strict. In our study, most did not meet all 3 requirements in the social communication domain. Previously, Young and Rodi reported that a high proportion of individuals only partially met one social communication criterion.23 This implies that patients less affected in social communication will not meet the diagnosis of ASD with the new diagnostic criteria. The current results imply that people diagnosed for the first time with the new criteria may not be diagnosed as ASD and may not receive appropriate treatment. Difficulty in obtaining certain treatments is a major concern and may be the most important implication for individuals who do not meet the criteria.26,27 Some investigators suggested that a solution might be to modify the DSM-5 criteria by relaxing the symptoms to be met in social communication, restricted and repetitive behaviour, or both. When they did so, they found that the change was too marked.28

The diagnosis of PDD-NOS would be most affected by the new criteria, with only 34.8% of the sample maintaining the ASD diagnosis.28,29 The diagnosis of PDD-NOS requires an impairment in reciprocal social interaction associated with impaired communication skills or atypical behaviour.1 With the DSM-5 criteria, individuals who have impairments in social communication but do not have restricted and repetitive behaviours or interests may not be diagnosed with ASD and it is unclear how they should be treated.9 In our study, 65.2% of the sample diagnosed as PDD-NOS with DSM-IV-TR changed to SPCD with DSM-5. Individuals with SPCD are characterised by their difficulties using language for social purposes, following the rules in communication context comprising nonliteral language and integrating language with nonverbal communicative behaviours. The only study examining long-term stability shows that pragmatic language impairment may be fairly stable in adulthood, but the sample size was not large enough to generalise the findings.30 This study compared adults with SPCD with adults with ASD and found that adults with SPCD had few behavioural differences compared to adults with ASD. It is still unclear how different SPCD is from ASD, and what clinical care or public health services will be available for people given the alternative diagnosis of SPCD.31 A recent study by Mandy et al. found no evidence that SPCD is qualitatively different from ASD. Rather, it appears to be on the borderlands of the autism spectrum, describing those with autistic traits that fall just below the threshold for an ASD diagnosis.32 SPCD may be clinically useful in identifying individuals with autistic traits who are not severe enough to be diagnosed as ASD, but who nevertheless require support. The Spanish public health services currently ensure that any person previously diagnosed with ASD before DSM-5 will not lose the support previously given, but access to school services and school intervention programmes may be at risk due to the lack of an actual diagnosis of ASD.

Regarding the differences between children diagnosed with ASD and SPCD in our sample, no statistically significant differences were found in school performance, outings with friends or linkage to mental health services between the 2 groups. However, subtle differences appear in treatment with psychotropic medication. Many patients with ASD have other psychiatric disorders or comorbid behavioural disturbances, such as aggression, self-harm, impulsivity, hyperactivity, anxiety, and mood disturbances. Psychotropic drugs are prescribed to improve these symptoms. In our study, 63.2% of the young people with ASD were given psychotropic medication compared to 33.3% of young people diagnosed with SPCD. Most of the ASD patients were treated with stimulants. These drugs have been shown to be effective in improving symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children with ASD. We also found more patients in the ASD group treated with antipsychotics, particularly risperidone and aripiprazole, which have been extensively investigated and shown to have efficacy in the treatment of irritability in children with ASD.33,34 This result could imply that a diagnosis of SPCD is less severe than that of ASD, with less impact on behaviour. Another difference found between the groups was a higher IQ in the SPCD group. As other authors have shown, high-functioning patients may not meet the DSM-5 criteria for ASD and be classified as SPCD.4,23 It remains to be assessed whether these patients need fewer services than those diagnosed with ASD or whether, with appropriate support, they could be better integrated into activities of daily living.29 It is also likely to be more difficult to detect high functioning patients at an early age with the new criteria and therefore, their treatment and improvement may be delayed.

Another interesting point to note is that the new International Classification of Diseases – ICD-11, available since May 2018, is more in line with the DMS-5. This means that it includes ASD, childhood dissociative disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders under the category of “autism”.35

We found no differences between the 2 groups in terms of the screening instruments (Social Communication Questionnaire and Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire). Specific measures are probably needed to assess pragmatic language. The Pragmatic Language Test and the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language are two standardised measures that are available and can serve as a starting point for quantifying SPCD.7 Further studies are needed to assess the impact and implications a diagnosis of SPCD and to better analyse the differences with ASD.

LimitationsThe present study has 2 main limitations. First, its retrospective design, which means that variables were not assessed specifically for the purpose of the study, and second, the sample size in some of the subgroups, which limits the conclusions.

However, the study has several strengths, in particular the homogeneity of the sample size (in terms of age and screening tools) and that all patients were assessed using ADI-R by experienced psychologists and psychiatrists from our department.

ConclusionsFurther studies, especially prospective studies with a larger number of patients, are required to confirm our results. In addition, studies that focus on the SPCD phenotype will be necessary to determine the differences in the progress of patients with respect to ASD, and more appropriate tools are needed for the diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank the Language Advisory Service of the University of Barcelona for their help in revising the English version of the manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Blázquez Hinojosa A, Lázaro Garcia L, Puig Navarro O, Varela Bondelle E, Calvo Escalona R. Sensibilidad y especificidad de los criterios diagnósticos DSM-5 en el trastorno del espectro autista en una muestra de niños y adolescentes españoles. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2021;14:202–211.