The World Health Organization has developed a new classification of mental disorders in Primary Health Care (PHC), the ICD-11-PHC, in which there are changes in the diagnostic criteria of anxiety and depression disorder. In addition, 2 screening instruments have been developed for the detection of anxious and depressive symptoms according to the criteria of the new classification.

ObjectivesTo evaluate the capacity of the Spanish version of the 2 brief scales Dep5 and Anx5 to identify cases of depression and anxiety in PHC in Spain.

MethodA cross-sectional study conducted by 37 PHC physicians who selected 284 patients with suspected emotional distress. This sample was administered the screening scales (Anx5 and Dep5) and a diagnostic instrument (Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised) contemplating the new ICD-11 criteria as used as gold standard.

ResultsThe Anx5, using a cut-off point of 3, showed a sensitivity of 0.75 and specificity of 0.53. Using a cut-off point of 4, the Dep5 showed a sensitivity of 0.48 and a specificity of 0.8. The 2 scales together, with a cut-off point of 3 for each, classified correctly 73,57% as cases or non-cases. The diagnosis most frequently observed was anxious depression.

ConclusionsThe screening scales for anxious and depressive symptoms (Anx5 and Dep5) are simple and easy-to-use instruments for assessing anxious and depressive symptoms in PHC. The reliability and validity data of each of the scales separately are limited but the figures improve when they are used together.

La Organización Mundial de la Salud ha desarrollado una nueva clasificación de trastornos mentales para su uso en Atención Primaria (AP), la CIE-11-AP, que incorpora cambios en los criterios diagnósticos de los trastornos de ansiedad y depresión. Como complemento, también ha desarrollado dos instrumentos de cribado de síntomas ansiosos y depresivos adaptados a los criterios de la nueva clasificación.

ObjetivosEvaluar la capacidad de la versión española de las 2 escalas breves (Dep5 y Anx5) para identificar casos de depresión y ansiedad en AP en una muestra de pacientes españoles de AP.

MétodoEstudio transversal realizado por 37 médicos de AP que seleccionaron 284 pacientes con sospecha de malestar emocional. A esta muestra se les administraron las escalas de cribado (Anx5 y Dep5) y, como comparador, un instrumento diagnóstico estructurado (Clinical Interview Schedule Revised) adaptado a los nuevos criterios CIE-11.

ResultadosLa Anx5, utilizando un punto de corte de 3, presentó una sensibilidad de 0,75 y una especificidad de 0,53. La Dep5 mostró una sensibilidad de 0,48 y una especificidad de 0,8 utilizando un punto de corte de 4. Las dos escalas utilizadas conjuntamente, con un punto de corte de 3 en ambas, clasificaban correctamente como casos o no casos un 73,57% de los sujetos. El diagnóstico más frecuentemente observado en la muestra fue el de depresión ansiosa.

ConclusionesLas 2 escalas de cribado de síntomas ansiosos y depresivos (Anx5 y Dep5) son instrumentos sencillos y fáciles de utilizar para evaluar síntomas ansiosos y depresivos en AP. Los niveles de fiabilidad y validez de cada una de las escalas por separado son limitados y mejoran cuando se utilizan de forma conjunta.

Anxiety and depression disorders are a major health problem due to their high prevalence, the emotional and physical distress and the functional limitations they cause.1–3 Although most of these disorders demand primary care (PHC) the rate of correct diagnosis (even in PHC centres with good resource availability) is approximately 50%.4

Subdiagnosis may be due to the fact that patients attended to in PHC usually present with ill-defined medical symptoms, with a short onset period and of mild intensity, which therefore do not easily fit into the diagnostic categories of mental illness classifications used in specialised care (CIE-105 and DSM-56).7 Other factors impacting subdiagnosis are: the lack of time professionals are able to give per patient; the complexity of the diagnostic algorithms used by the international classifications of mental illness and the limitations of the current assessment tools (both structured diagnostic interviews and self-administered questionnaires).8,9 Improvement of the diagnostic capacity would offer PHC professionals with clinically useful diagnostic tools, complemented by validated, reliable, simple detection tools that take up little time and may be adapted to new information and communication technologies.10,11

To achieve this, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has developed a new classification of mental disorders and of specific behaviour for PHC (ICD-11-PHC), which, among other new issues, proposes the modification of the time criterion required for the diagnosis of anxiety. Current classifications5,6 for diagnosis of an anxiety disorder require that the onset of symptoms have had a duration of several months. The new classification modifies this criterion and considers anxiety as pathological when it has lasted for over 2 weeks, equalling the time criterion currently in force for depressive symptoms. Justification for this change comes from the demonstration that in cases of comorbid anxiety and depression, even when duration is short, this is a good predictor of psychopathology and disability after 6 months of follow-up.12 Another novelty of the ICD-11-PHC is its inclusion of a new diagnostic category called “mixed subclinical depression and anxiety”, in which although significant symptoms are present both for anxiety and for depression, they are not of sufficient weight to meet with the diagnostic criteria of anxiety or depression.13

The WHO has also promoted the development of 2 screening scales to be used in PHC: one for anxiety (Anx5) and the other for depression (Dep5). They are brief scales (5 items) which, in order to shorten administration time, are structured into 2 item groups: the first group consists of 2 key questions, which always have to be asked, and the second group is formed by 3 additional questions, which may be asked only in the case that a positive answer has been given to one of the 2 key questions. In the validation study, the Dep5 scale presented with 90% sensitivity and 88.5% specificity, and the Anx5 with 79.8% sensitivity and 72.5% specificity.14

This study researched the ability of the Spanish version of the 2 screening scales, Dep5 and Anx5, to identify cases of depression and anxiety in patients attended to by PHC centres in Spain. An additional aim was to determine what scoring was to be considered as threshold for the suspicion of depression and anxiety, in accordance with the new criteria proposed by the ICD-11-PHC classification.

MethodThirty seven PHC physicians who practised in public PHC centres in Aragón, Asturias, Catalonia, Extremadura, Galicia, Madrid and the Basque Country participated in the study. They were selected according to their interest in the project and the availability of resources and infrastructure to conduct the research.

A descriptive, cross-sectional design was used among the total population of patients over 18 years of age who normally went to PHC practices, to those whose doctor suspected could suffer from emotional distress. The participating physicians were instructed to use a low mental illness suspicion threshold, to increase the probability of including a group of patients without psychiatric illnesses in the study and to therefore be able to assess the ability of the scales to differentiate between cases and non-cases. The study was conducted following the process of translation and adaptation of WHO tools.15 The study protocol was approved by the WHO Research Ethics Committee and the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias.

The PHC physician filled in the form for the patients who participated in the study, which included the Anx5 and Dep5 scales, always asking the first 2 questions (key questions) and only the remaining 3 if the patient replied in the affirmative to one of the two. After this, the patients were interviewed by a research assistant, who was unaware of the previous assessment result, and who gave the patient the Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R) questionnaire. The CIS-R diagnostic interview was adapted to perform diagnoses with the requirements proposed in the ICD-11-PHC, including: the duration period necessary for the diagnosis of anxiety of only 2 weeks; the diagnosis of “anxious depression” for patients who met with the criteria of anxiety and depression, and the diagnosis of “mixed subclinical depression and anxiety”.

The Anx5 scales consists of 2 key questions: A1) Have you felt nervous or anxious almost every day for the last 2 weeks?, and A2) Have you felt incapable of controlling your concerns in the last 2 weeks?, and the 3 additional questions: A3) In the last 2 weeks has it been difficult for you to relax? A4) In the last 2 weeks have you felt so worried that you cannot sit still? and A5) In the last 2 weeks have you been afraid that something horrible could happen? The Dep5 scale has 2 key questions: D1) In the last 2 weeks have you felt depressed every day? And D2) In the last 2 weeks have you noticed that certain activities interest you or please you less?, plus the 3 additional questions: D3) Has it been difficult to concentrate in the last 2 weeks?; D4) Have you felt useless in the last 2 weeks? and D5) Have you wanted to die or had thoughts of death in the last 2 weeks?

Data analysisTo determine the validity of the Anx5 and Dep5 scales their results (number of items given a positive response to) were compared with the diagnoses of anxiety or depression obtained through the structured clinical CIS-R interview, adapted to the ICD-11-PHC criteria. Positive and negative predictive values were calculated using the Bland-Altman16 formula. The optimum cut-off points to determine a “possible case” were agreed using the Youden index.17 STATA software version 12 and R statistical software version 3.1.3 were used.

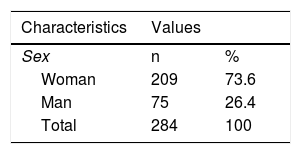

ResultsTwo hundred and eighty four patients were studied. Table 1 lists the general characteristics of the sample: sex, age and mean score in the anxiety and depression scales.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristics | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | n | % |

| Woman | 209 | 73.6 |

| Man | 75 | 26.4 |

| Total | 284 | 100 |

| Age | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49,5 | 15,1 |

| Score in the scales | Mean | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Score in the Dep5 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 2.6−3.0 |

| Score in the Anx5 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 3.0−3.3 |

SD: Standard Deviation; 95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval.

Diagnostic assessment made using the CIS-R showed the following data of diagnostic frequency: 145 cases (51.1%) presented a diagnosis of anxious depression, 63 cases (22.2%) of anxiety disorder, 15 cases (5.3%) of depressive disorder, 8 cases (2,7%) of mixed subclinical depression and anxiety and 53 cases (18.7%) were diagnosis-free.

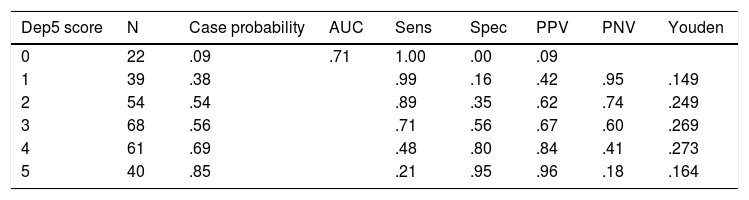

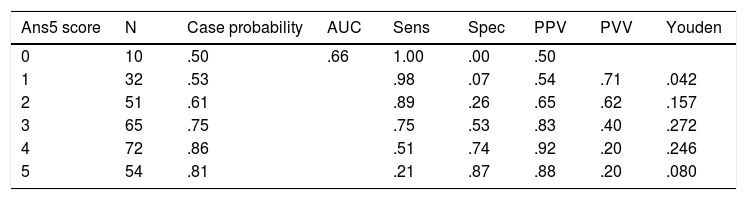

Table 2 demonstrates the precision of the Dep5 scale for detecting cases of depression and anxious depression. The most appropriate cut-off score for the consideration of a case was 4. Table 3 demonstrates the same data relating to the Anx5 scale. In this case the optimum cut-off point was 3.

Diagnostic precision of the 5 item scale of depression (Dep5) to identify people with a clinical diagnosis of depression (without anxiety) or of anxious depression.

| Dep5 score | N | Case probability | AUC | Sens | Spec | PPV | PNV | Youden |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 22 | .09 | .71 | 1.00 | .00 | .09 | ||

| 1 | 39 | .38 | .99 | .16 | .42 | .95 | .149 | |

| 2 | 54 | .54 | .89 | .35 | .62 | .74 | .249 | |

| 3 | 68 | .56 | .71 | .56 | .67 | .60 | .269 | |

| 4 | 61 | .69 | .48 | .80 | .84 | .41 | .273 | |

| 5 | 40 | .85 | .21 | .95 | .96 | .18 | .164 |

AUC: Area under the curve; PNV: Predictive negative value; PPV: Predictive positive value; Sens: Sensitivity; Spec: Specificity.

The PPV and PNV are calculated using the Bland-Altman (1994) formula. The optimized cut-off points were selected using the Youden (1950) index.

Diagnostic precision of the 5 item scale of anxiety (Ans5) to identify people with a clinical diagnosis of anxiety or anxious depression.

| Ans5 score | N | Case probability | AUC | Sens | Spec | PPV | PVV | Youden |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | .50 | .66 | 1.00 | .00 | .50 | ||

| 1 | 32 | .53 | .98 | .07 | .54 | .71 | .042 | |

| 2 | 51 | .61 | .89 | .26 | .65 | .62 | .157 | |

| 3 | 65 | .75 | .75 | .53 | .83 | .40 | .272 | |

| 4 | 72 | .86 | .51 | .74 | .92 | .20 | .246 | |

| 5 | 54 | .81 | .21 | .87 | .88 | .20 | .080 |

AUC: Area under the curve; PNV: Predictive negative value; PPV: Predictive positive value; Sens: Sensitivity; Spec: Specificity.

The PPV and PNV are calculated using the Bland-Altman (1994) formula. The optimized cut-off points were selected using the Youden (1950) index.

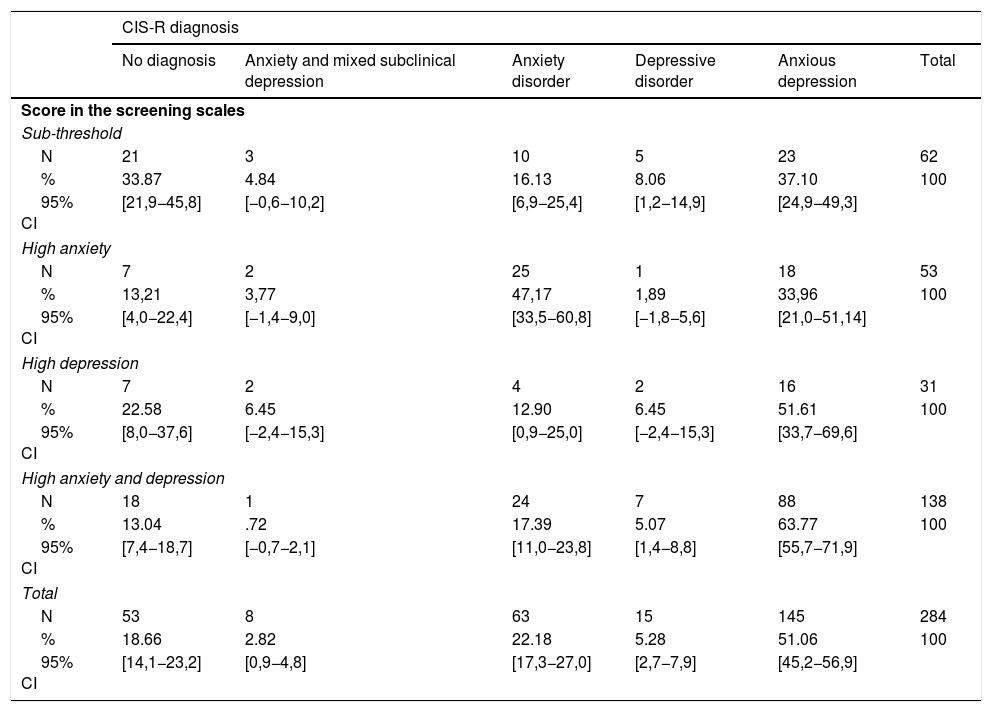

Table 4 shows the relationship between the results of the 2 screening scales and the specific CIS-R diagnoses. A cut-off point of 3 was used for both scales, which proved to be the most favourable condition. In this situation, the screening scales correctly classified as cases or non-cases 73.57% (n = 209) of the 284 participating individuals, including 185 patients who obtained a positive score on the screening scales and who were diagnosed with some type of disorder by the CIS-R, and 24 patients with a negative score on the scales and without a diagnosis or with sub-threshold symptoms in the CIS-R. The screening scales correctly identified 83.32% of positive cases (185 of 222 cases) and 38.71% (24 of 62 cases) of non-cases.

Relationship between the diagnostic groups based on the results of the 2 screening scales and specific diagnoses using the CIS-R.

| CIS-R diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No diagnosis | Anxiety and mixed subclinical depression | Anxiety disorder | Depressive disorder | Anxious depression | Total | |

| Score in the screening scales | ||||||

| Sub-threshold | ||||||

| N | 21 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 23 | 62 |

| % | 33.87 | 4.84 | 16.13 | 8.06 | 37.10 | 100 |

| 95% CI | [21,9−45,8] | [−0,6−10,2] | [6,9−25,4] | [1,2−14,9] | [24,9−49,3] | |

| High anxiety | ||||||

| N | 7 | 2 | 25 | 1 | 18 | 53 |

| % | 13,21 | 3,77 | 47,17 | 1,89 | 33,96 | 100 |

| 95% CI | [4,0−22,4] | [−1,4−9,0] | [33,5−60,8] | [−1,8−5,6] | [21,0−51,14] | |

| High depression | ||||||

| N | 7 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 31 |

| % | 22.58 | 6.45 | 12.90 | 6.45 | 51.61 | 100 |

| 95% CI | [8,0−37,6] | [−2,4−15,3] | [0,9−25,0] | [−2,4−15,3] | [33,7−69,6] | |

| High anxiety and depression | ||||||

| N | 18 | 1 | 24 | 7 | 88 | 138 |

| % | 13.04 | .72 | 17.39 | 5.07 | 63.77 | 100 |

| 95% CI | [7,4−18,7] | [−0,7−2,1] | [11,0−23,8] | [1,4−8,8] | [55,7−71,9] | |

| Total | ||||||

| N | 53 | 8 | 63 | 15 | 145 | 284 |

| % | 18.66 | 2.82 | 22.18 | 5.28 | 51.06 | 100 |

| 95% CI | [14,1−23,2] | [0,9−4,8] | [17,3−27,0] | [2,7−7,9] | [45,2−56,9] | |

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval; CIS-R: Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised.

In our study a sample of 284 patients attending PHC whose doctor suspected emotional distress was studied, to assess the psychometric properties of 2 screening scales for anxious and depressive symptoms. The two scales were able to correctly identify 82.95% of positive cases of anxiety, depression or “anxious depression” diagnosed according to the structured diagnostic interview used as a comparator (CIS-R), adapted to the diagnostic criteria of the ICD-11-PHC classification.

In the sample studied the frequent coexistence of anxious and depressive symptoms in PCH was observed.18,19 This data, together with the evidence that patients with comorbid depression and anxiety differ from those who only have depression the clinical course and prognosis and who should also be treated with different therapeutic strategies,20 highlights the changes proposed in the diagnostic criteria. Thus it is suspected that a percentage of patients diagnosed with anxious depression under the new criteria would only have been diagnosed with depression under the criteria of the current classifications because the demand for PHC is often too early to meet the current time criteria for the diagnosis of anxiety.

Both scales (Anx5 and Dep5) presented with limited levels of reliability and validity taking into account the available evidence in PHC.4 They are easy to apply, take up little time and do not require memorising complex diagnostic algorithms which PHC physicians would find difficult to use.21

The fact that, as data from the present study show, diagnostic accuracy is higher when the anxiety and depression scales are used together than when they are used separately, would justify the use of tools capable of simultaneously detecting anxious and depressive symptoms for screening mental illness in PHC.

Among the limitations of the study is that it was not designed as a prevalence study, so the morbidity data cannot be considered representative of the population. A bias was observed in the simple in gender selection (approximately 4/1); despite the higher proportion of women with depressive disorders, a ratio closer to 3/2 would have been expected. Furthermore, the over-inclusion of pathological cases which were made in accordance with the protocol, could have meant that the results of the psychometric characteristics of the questionnaire were biased towards overestimation. In contrast, it is probable that there was a pessimistic proportion of non-cases correctly identified in this sample since it is likely that many easily identifiable non-cases were not included in the study.

To conclude, the 2 screening scales of anxious and depressive symptoms (Anx5 and Dep5) used to detect anxiety and depression according to the new criteria proposed by the WHO for ICD-11 are simple and easy to apply, but their practical use is conditioned by low levels of reliability which slightly improve when they are used together.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Iglesias García C, López García P, Ayuso Mateos JL, García JÁ, Bobes J. Detección de ansiedad y depresión en Atención Primaria: utilidad de 2 escalas breves adaptadas a los nuevos criterios CIE-11-AP. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2020;14:196–201.