Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) is a neurodegenerative pathology belonging to the group of prion diseases or transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. It is caused by the central nervous system deposit of a pathological isoform of the normal prion protein (PrPc) present in all mammals. The mechanism by which this conformational change is produced is unknown. The accumulation of the pathological prion protein (PrPsc) gives rise to a neural degeneration that provokes a rapidly progressive fatal neurological deterioration.

There are three forms of CJD: sporadic (sCJD), familial and acquired. The sporadic form represents 85% of the cases, with greater incidence in individuals approximately 60 years old; and 90% of the patients die within a year of symptom onset, with a mean survival of 6 months.1

The classic clinical presentation of sCJD includes rapidly progressive dementia, myoclonus, and pyramidal, extrapyramidal and cerebellar signs. Although it is less frequent, the disease can begin with non-specific psychiatric signs and symptoms such as personality changes, behavioural changes, anxiety, depression and even as a psychotic condition, which can make initial diagnosis more difficult.2–11

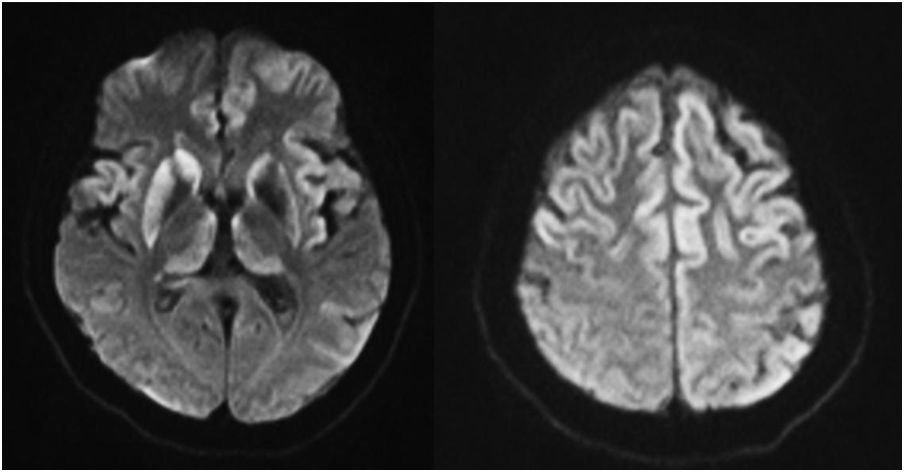

Diagnosis is based on the clinical features and the neurological examination findings, together with the presence of alterations in the diffusion-weighted sequences (DWI) or brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan using fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) in the caudate nucleus and putamen or in at least two cortical regions,12 an electroencephalogram (EEG) showing periodic sharp wave complexes superimposed on a slow background rhythm,13 and/or cerebrospinal fluid positive for 14-3-3 protein.1 Nevertheless, these findings are not pathognomonic and their normality does not rule out the disease. Definitive diagnosis is established using pathological studies that show spongiform degeneration, neuron loss and gliosis.1 There is currently no cure, with treatment being merely symptomatic.

We present the case of a 53-year-old Columbian female, divorced, having a 20-year-old son. The patient had no other direct family members and a very limited social support network. There was no personal or familial psychiatric history. Condition began with delusions of persecution that required involuntary admission to the Acute Psychiatric Unit. Blood tests, urine analysis for drugs and cranial computed tomography (CT) scan were performed with normal results. During hospitalisation, treatment was begun with risperidone up to 6mg/day with good response. Patient was discharged with the diagnosis of unspecified psychotic disorder and prescribed treatment with 9mg/day paliperidone.

During outpatient mental health unit follow-up, the delusional disorder reappeared at 8 months; this was considered secondary to poor therapeutic adherence, requiring new admission to the Psychiatric Unit. This time pharmacological control of psychotic signs and symptoms was incomplete, and slowing in gait and cognitive deficits were also detected. Given the lack of familial support, she was transferred to a medium-term community health centre upon discharge and evaluation by an outpatient neurology unit was requested. The outpatient brain MRI scan showed T2 hyperintensity and FLAIR with diffusion restriction of the frontal and insular cortex, of the thalamus and of the basal ganglia, predominantly right (Fig. 1). The EEG revealed overall slowing of moderate encephalic nature.

At that time, the patient presented severe temporal and spatial disorientation, walking limitation, generalised pyramidal syndrome and myoclonus. At the functional level, there was complete loss of personal autonomy, with no language use, and the patient was confined in a wheelchair. She presented significant behavioural changes and the spinal tap could not be carried out.

Our patient was diagnosed with probable sCJD, based on internationally-agreed diagnostic criteria,1 because she presented rapidly progressive cognitive deterioration, extrapyramidal signs, pyramidal syndrome and akinetic mutism.

It is worthwhile noting that, although psychiatric symptoms are considered rare, they are found in sCJD as prodromal symptoms; in early stages of the disease they are found in up to 40% of the cases.14 However, presentation as a pure psychotic condition over so many months of development is not typical and the predominantly frontal alterations in our patient's diffusion sequences in the MRI scan indicate correlation with the initial signs and symptoms.

In short, our case illustrates the need to consider CJD as a differential diagnosis in patients with psychotic symptoms or affective disorders resistant to conventional psychiatric treatment. The frequent lack of biological markers for diagnosing psychiatric illnesses can make the initial diagnosis more difficult to reach, especially in cases of atypical presentation.15,16

Consequently, with patients for whom there is a high level of initial CJD suspicion, but normal EEG and neuroimaging tests, repeating these analyses over the course of the disease is recommended.14

Please cite this article as: Ruiz M, del Agua E, Piñol-Ripoll G. Psicosis como inicio de enfermedad de Creutzfeldt-Jakob esporádica. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2019;12:131–133.