As yet, the relation between personality traits and working alliance (WA) has not been investigated in subjects affected by borderline personality disorder (BPD).

MethodA sample of forty-nine BPD subjects who completed a module of Sequential Brief Adlerian Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (SB-APP) of 40 sessions has been recruited. Before the onset of psychotherapy an assessment was made with Clinical Global Impression (CGI), Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Symptom Checklist Revised 90 (SCL-R 90), and with Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI). At the end of their psychotherapy, patients were requested to rate the level of WA by means of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-S).

ResultsMultiple linear regression analysis has identified three variables as independent predictors of WAI-S total score: subjects with lower Harm Avoidance (HA), older patients, and subjects with a higher psychopathology level had a better WAIS total score.

DiscussionThese preliminary results showed that the pattern of alliance with the therapist in subjects with BPD could be related not only to weakness of character, but also to a temperamental trait typical of inhibited and avoidant subjects.

ConclusionThese results suggest that an assessment of temperament in subjects affected by BPD at intake could be useful to detect the subjects who have more difficulties in building a good WA and in order to improve the technical interventions and settings for psychotherapy of BPD subjects with higher HA.

Hasta el momento no se ha investigado la relación entre los rasgos de la personalidad y la alianza terapéutica en individuos con trastorno límite de la personalidad (TLP).

MétodosSe reclutó para el estudio una muestra de 49 individuos con TLP que completaron un módulo de la Sequential Brief Adlerian Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (SB-APP) de 40 sesiones. Antes del inicio de la psicoterapia, se realizó una evaluación con las escalas Clinical Global Impression (CGI), Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Symptom Checklist Revised 90 (SCL-R 90), y con el Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI). Al final de la psicoterapia, se pidió a los pacientes que evaluaran el nivel de la alianza terapéutica mediante el Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-S).

ResultadosUn análisis de regresión lineal múltiple ha identificado 3 variables como factores predictivos independientes para la puntuación total del WAI-S: los individuos con una evitación del daño menor, los pacientes de mayor edad y los individuos con mayor nivel de psicopatología presentaron una mejor puntuación total del WAI-S.

DiscusiónEstos resultados preliminares pusieron de manifiesto que el patrón de la alianza con el terapeuta en los individuos con TLP podría estar relacionado no solo con la debilidad de carácter, sino también con un rasgo del temperamento característico de los individuos inhibidos y con tendencia a la evitación.

ConclusiónEstos resultados sugieren que una evaluación del temperamento en los individuos que presentan un TLP podría ser útil para detectar a aquellos que tienen más dificultades para establecer una buena alianza terapéutica y para mejorar las intervenciones técnicas y los contextos de la psicoterapia de los pacientes con TLP con una mayor evitación del daño.

The concept of therapeutic alliance, referring to the quality of the working relationship between client and therapist, is rooted both in psychodynamic theory (transference concept) and in Roger's work on client-centered therapy.1 Since then, the notion has evolved in a pan-theoretical construct and several researchers have shown growing interest in this field of study. According to a popular definition proposed by Bordin,2 therapeutic alliance consists of three related components: (1) agreement between client and therapist on treatment goals (Goal), (2) agreement between client and therapist on how to achieve those goals (Task), and (3) development of a personal bond between therapist and client (Bond).

A good therapeutic alliance is one of the most important outcome predictors or process indicator in the treatment of several Mental Disorders.3,4 Therapeutic alliance is strictly related to treatment adherence;5,6 inadequate alliance between therapist and client often leads to early interruption of treatment.7,8 Moreover, two cases of meta-analysis demonstrate that treatment outcome and therapeutic alliance are strictly related in psychotherapy.3,9 Therefore, therapeutic alliance is considered critical for success in all types of psychotherapy by numerous therapists; maintaining a stable and good therapeutic alliance is regarded as an endpoint of psychotherapy. The tendency to “pushing the limits” in building therapeutic alliance is an affective core characteristic of subjects with BPD. This is not necessarily related to selfdamaging or disrupting behaviors but it may produce a high rate of difficulties in clinical management.10 For this reason several authors focused on WA predictors particularly for the treatment of subjects with BPD.10

In psychotherapy, diagnostic variables do not seem to predict the level of WA; on the other hand, the quality of current and past relationships is often associated to WA.11

Only few predictors of a good or bad therapeutic alliance in subjects with psychiatric disorders have been analyzed in literature.12,13 Overall interpersonal sensitivity and interpersonal problems seem to be the best predictors of a difficulty in building a strong therapeutic alliance in outpatients with different mental disorders.14

Remarkable difficulties in building a good and stable therapeutic alliance have been detected in subjects with BPD15,18 and in patients suffering from psychiatric disorders with a high comorbidity with Personality Disorders–e.g. Eating Disorders16,17 and Addictions. Such difficulties seem to be related to disturbances in attachment process18 and to a prevalent pattern of emotional dysregulation. Nevertheless, the role of personality dimensions in the prediction of WA is still unclear.

According to the TCI, subjects with BPD are characterized by a high HA and a very low Self Directedness (SD)19: the low SD seems to indicate that character development in BPD patients is more fixed and immature than those of healthy comparison subjects.20 Moreover, only males with BPD seem to present an “explosive” temperament as suggested by Cloninger,21 characterized by high scores in NS,22 HA and Reward Dependence (RD).

The aim of this study is to detect the temperament and character predictors of WA in subjects with BPD after one year of outpatient combined treatment. To the best of our knowledge, no data on the role of TCI-evaluated personality dimensions in relation to WA in subjects with BPD are currently available in literature.

Because both personality dimensions and WA could be related to the state psychopathology, such relation has been controlled not only for personal features but also for general psychiatric symptomatology, as well as for clinical and psychosocial severity at intake.

Materials and methodsSubjectsForty-nine subjects with BPD were recruited among BPD patients followed with usual treatment methods at the Mental Health Centres of Chivasso and of Settimo Torinese between January 1st, 2004 and January 1st, 2007.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) a full diagnosis of BPD according to criteria of DSM-IV-TR,23 (2) uniformity of gender distribution within the sample, (3) age range between 20 and 55 years, (4) absence of acute full-syndrome Axis I disorders requiring inpatient treatment, (5) absence of actual Substance Dependence or Abuse Disorders,23 (6) absence of mental retardation, (7) no previous experiences with structured psychotherapy, and (8) willingness to give informed consent to participate both in the study and in the treatment program.

Diagnostic assessment for Axis I and Axis II disorders has been carried out at intake by three trained psychiatrists, with the support of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-OP I, and SCID II).24,25

31 patients with BPD were excluded from the sample for the following reasons: (1) age out of the established range (No.=2); (2) comorbidity of acute and severe full-syndrome Axis I disorder (No.=14) requiring inpatient treatment, including Mood Disorders (No.=9), Psychotic Disorders (No.=4), Eating Disorder (No.=1); (3) comorbidity with Mental Retardation (No.=1); (4) presence of acute substance abuse disorder (No.=8), and (5) patients who met the inclusion criteria but refused to participate in the study or to sign an informed consent (No.=6).

Subjects were assessed before the onset of psychotherapy with two rating scales such as GAF and CGI, and two self administered questionnaires such as SCL-R 90, TCI. At the end of psychotherapy treatment (around one year later) patients were requested to rate the level of WA by means of the Working Alliance Scale-Short Form (WAI-S). Only patient assessment of WA has been measured in the study, because client perception of therapeutic alliance is more reliable than therapist or observer ratings, as suggested by literature.

All the raters (three) were adequately trained in the use of the rating scales (CGI, GAF), in order to ensure good internal consistency and inter-rater reliability.

Treatment programAll the selected subjects have been treated with a combination of “as usual treatment” and psychodynamic oriented psychotherapy such as the SB-APP.

The “as usual treatment”26 consist in the combination of: (1) medication, used to help control any target symptoms, which usually fall into such categories as cognitive-perceptual, affect dysregulation, or impulsive behavioral dyscontrol; (2) non structured psycho-education sessions taken by the same therapist; (3) rehabilitative interventions (social skill training and/or working support) taken by nurses or educators.

SB-APP is a time-limited sequential psychodynamic psychotherapy (40 weekly sessions of 50min each), based on Alfred Adler's theory of Individual Psychology27 and specifically addressed to the setting and practice of community Mental Health Services (MHS). SB-APP is divided into sequential and repeatable modules. Only the first module was administered to the patients. SB-APP is an adaptation of the Brief Adlerian Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (B-APP),27 that is a time limited psychodynamic psychotherapy used within a range of settings to treat various disorders.16,28,29

SB-APP is focused specifically on four Personality Functioning Levels (PFL). These are assessed by the therapists on the basis of symptoms, quality of interpersonal relationships, overall social behaviors, cognitive and emotional patterns, and defense mechanisms.30 At PFL 1, SB-APP is focused on preventing disruptive acting-out by providing reality testing by strengthening self-reflective functions and identity. At PFL 2, the approach is focused on increasing empathy through validating thoughts and emotions and decreasing the sense of emptiness, egocentrism, and dependence. At PFL 3, therapy aims at reducing idealization and increasing continuity and adaptation. At PFL 4, it attempts to develop increased tolerance for ambivalence, help patients overcome conflicts, enhance autonomy, and increase positive attitudes toward the project.27

SB-APP is devoted to building a favorable WA.

Psychotherapists who administered SB-APP (No.=4) had been specifically trained in SB-APP application at a certified school of psychotherapy in Turin, Italy (S.A.I.G.A., Italian Adlerian Society Group and Analysis, certified by the Italian Ministry of University Studies in 1994).

Assessment instrumentsGlobal Assessment Functioning (GAF): The Goldman's Global Assessment of Functioning Scale evaluates the level of social and occupational functioning31 of the individual. The validity and reliability of this instrument have been verified in several studies.32

Clinical Global Impression (CGI): This is a well-known assessment tool, administered by clinicians in order to evaluate the severity of an illness (item 1), according to a score between 0 (non-assessed) and 7 (extreme severity).

Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90R): The SCL-90R33 is a self-report tool aimed at identifying psychopathological distress. Such questionnaire measures symptomatology levels on nine different scales, which describe as many psychopathological dimensions: I. Somatisation, II. Obsessive-Compulsive, III. Interpersonal Sensitivity, IV. Depression, V. Anxiety, VI. Hostility, VII. Phobic Anxiety, VIII. Paranoid Ideation, IX. Psychoticism. The SCL-90R has proved useful in the screening of psychopathological profiles of severe psychiatric inpatients.34

Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI). The TCI35 is an inventory divided into seven independent dimensions. Four of these (NS, HA, RD, and Persistence [P]) assess temperament. Cloninger refers to temperament as a set of emotional responses that are moderately heritable, stable throughout life, and mediated by neurotransmitter functioning in the central nervous system; such emotional responses provide a clinical description based on the scores attained by each subject with regard to a set of opposing temperamental features.36,37 Briefly, NS expresses the level of activation of exploratory activity. Low NS scores correspond to low explorative activity, poor initiative, insecurity, and unresponsiveness to novelty and change, whereas high NS scores express the opposite characteristics. HA reflects the efficiency of the behavioral inhibition system. Individuals with high HA are described as extremely careful, passive and insecure, and prone to react with a high rate of anxiety and depression to stressful events. RD reflects the maintenance of rewarded behavior. Individuals with high levels of RD are described as sentimental and easily influenced by others. P expresses maintenance of behavior as resistance to frustration. High P expresses the tendency to maintain unrewarded behaviors and correlates with rigidity and obsessiveness.

The remaining three dimensions of the TCI (Self-Directedness [SD], Cooperativeness [C], and Self-Transcendence [ST]) are intended to evaluate character; they are considered as personality traits acquired through experience. SD expresses the degree to which the self is viewed as autonomous and integrated. C reflects the extent in which the self is viewed as a part of society. ST expresses the degree to which the self is viewed as an integral part of the universe. Low SD and C scores appear to be the most important predictors of categorical diagnosis of a DSM Axis II disorder.21,37 The TCI test displays a good internal consistency (range, 0.76–0.89).37

Working Alliance Inventory - Short Form, client version (WAI-S): The WAI-S38 is a trans-theoretical measure that was designed to be applied to different therapeutic orientations and modalities; it is one of the most frequently used questionnaires in the assessment of WA. The WAI-S (short form) used in our study is a 12-item, self-report questionnaire consisting of three subscales designed to assess three primary components of the WA: (1) how closely client and therapist agree on and are mutually engaged in the goals of treatment (Goal), (2) how closely client and therapist agree on how to reach the treatments goals (Task), and (3) the degree of mutual trust, acceptance and confidence between client and therapist (Bond). The composite score is used as a global measurement of WA. Respondents were asked to rate each statement on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Total score ranged from 12 to 84, with higher scores indicating a stronger WA.

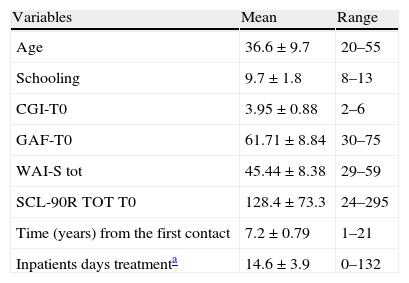

Data analysisAll data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences. The initial step was a description of our sample of BPD subjects (Table 1). An evaluation through a T-test for independent samples has been made to compare males and females.

Sample description.

| Variables | Mean | Range |

| Age | 36.6±9.7 | 20–55 |

| Schooling | 9.7±1.8 | 8–13 |

| CGI-T0 | 3.95±0.88 | 2–6 |

| GAF-T0 | 61.71±8.84 | 30–75 |

| WAI-S tot | 45.44±8.38 | 29–59 |

| SCL-90R TOT T0 | 128.4±73.3 | 24–295 |

| Time (years) from the first contact | 7.2±0.79 | 1–21 |

| Inpatients days treatmenta | 14.6±3.9 | 0–132 |

| Variables | Number (%) |

| Gender | |

| Males | 18 (36.7) |

| Females | 31 (63.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Not married | 25 (51.0) |

| Married | 21 (42.9) |

| Divorced | 3 (6.1) |

| Axis I | |

| Eating disorders NOS | 13 (26.5) |

| Depressive disorder | 5 (10.2) |

| Distymia | 15 (30.6) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 1 (2.0) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3 (6.1) |

| No axis I disorders | 12 (24.5) |

| Medicationa | |

| Yes | 47 (96)* |

| Not | 2 (4) |

CGI-T0, Clinical Global Impression at T0; GAF-T0, Global Assessment of Functioning at T0; WAI-S T0, Working Alliance Inventory-Short Form at T0; SCL-90R TOT T0, Symptom Checklist 90 Revised Total score at T0. *SSRI (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor) No.=28; SNRI (Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor) No.=16; SGA (Second Generation Antipsychotics) No.=11; Mood Stabilizers No.=16; BDZ (Benzodiazepines) No.=25.

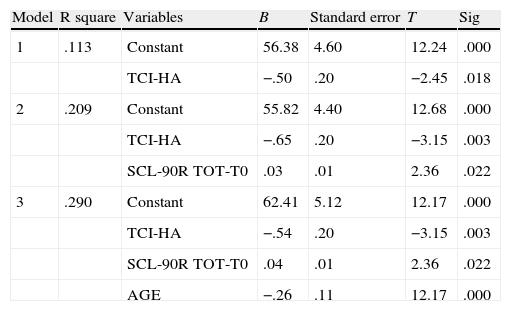

Finally, a series of multiple linear regressions (stepwise forward) has been calculated to detect the independent predictors of overall WAI-S scores and of the three subscales (Goal; Task; Bond) of WAI-S (Tables 2–4).

Independent predictors of working alliance at T12: multiple linear regression (stepwise forward).

| Model | R square | Variables | B | Standard error | T | Sig |

| 1 | .113 | Constant | 56.38 | 4.60 | 12.24 | .000 |

| TCI-HA | −.50 | .20 | −2.45 | .018 | ||

| 2 | .209 | Constant | 55.82 | 4.40 | 12.68 | .000 |

| TCI-HA | −.65 | .20 | −3.15 | .003 | ||

| SCL-90R TOT-T0 | .03 | .01 | 2.36 | .022 | ||

| 3 | .290 | Constant | 62.41 | 5.12 | 12.17 | .000 |

| TCI-HA | −.54 | .20 | −3.15 | .003 | ||

| SCL-90R TOT-T0 | .04 | .01 | 2.36 | .022 | ||

| AGE | −.26 | .11 | 12.17 | .000 |

1 Predictors: (Constant), TCI-HA; 2 Predictors: (Constant), TCI-HA, SCL-90R TOT-T0; 3 Predictors: (Constant), TCI-HA, SCL-90R TOT-T0, AGE.

Note. Variables included in the analysis: TCI: NS, novelty seeking; HA, harm avoidance; RD, reward dependence; PP, persistence; SD, self directedness; CC, cooperativeness; ST, self transcendence; AGE; Schooling; SCL-90R TOT-T0; CGI-T0; GAF-T0; duration of contact with MHS.

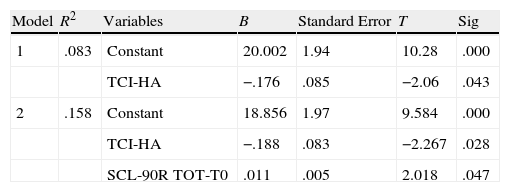

Independent predictors of working alliance subscale “Task” at T12: multiple linear regression (stepwise forward).

| Model | R2 | Variables | B | Standard Error | T | Sig |

| 1 | .083 | Constant | 20.002 | 1.94 | 10.28 | .000 |

| TCI-HA | −.176 | .085 | −2.06 | .043 | ||

| 2 | .158 | Constant | 18.856 | 1.97 | 9.584 | .000 |

| TCI-HA | −.188 | .083 | −2.267 | .028 | ||

| SCL-90R TOT-T0 | .011 | .005 | 2.018 | .047 |

1 Predictors: (Constant), TCI-HA; 2 Predictors: (Constant), TCI-HA, SCL-90R TOT T0.

Note. Variables included in the analysis: TCI: NS, novelty seeking; HA, harm avoidance; RD, reward dependence; PP, persistence; SD, self directedness; CC, cooperativeness; ST, self transcendence; AGE; Schooling; SCL-90R TOT-T0; GAF-T0; CGI-T0; duration of contact with MHS.

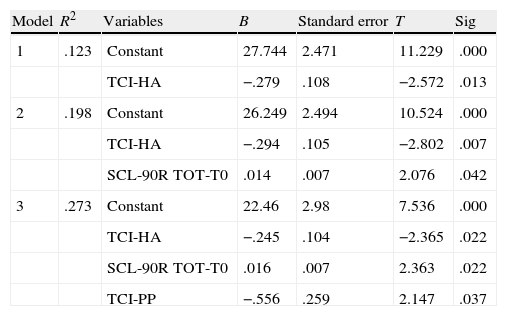

Independent predictors of working alliance subscale “Bond” at T12: multiple linear regression (stepwise forward).

| Model | R2 | Variables | B | Standard error | T | Sig |

| 1 | .123 | Constant | 27.744 | 2.471 | 11.229 | .000 |

| TCI-HA | −.279 | .108 | −2.572 | .013 | ||

| 2 | .198 | Constant | 26.249 | 2.494 | 10.524 | .000 |

| TCI-HA | −.294 | .105 | −2.802 | .007 | ||

| SCL-90R TOT-T0 | .014 | .007 | 2.076 | .042 | ||

| 3 | .273 | Constant | 22.46 | 2.98 | 7.536 | .000 |

| TCI-HA | −.245 | .104 | −2.365 | .022 | ||

| SCL-90R TOT-T0 | .016 | .007 | 2.363 | .022 | ||

| TCI-PP | −.556 | .259 | 2.147 | .037 |

1 Predictors: (Constant), TCI-HA; 2 Predictors: (Constant), TCI-HA, SCL-90R TOT T0; 3 Predictors: (Constant), TCI-HA, SCL-90R TOT T0, PP (persistence).

Note. Variables included in the analysis: TCI: NS, novelty seeking; HA, harm avoidance; RD, reward dependence; PP, persistence; SD, self directedness; CC, cooperativeness; ST, self transcendence; AGE; Schooling; SCL-90R TOT-T0; GAF-T0; CGI-T0; duration of contact with MHS.

Table 1 represents the features of the full sample of patients included in this study. Only 24.5% of subjects did not present any Axis I disorder comorbidity. Mean and standard deviation of CGI, GAF, SCL-90R total score and WAI-S total score at T0 were shown in the same table. The subjects included in this study were outpatients treated within an “as usual” community health treatment program from 1 to 21 years (Table 1).

Comparison between males and femalesNo remarkable difference emerged between the male and female groups. Therefore, gender was not considered a confounding variable in regression analysis (data will be available for the interested readers).

Predictors of working allianceA linear multiple regression (stepwise forward) showed that only three variables (at intake) predicted the level of Working Alliance in the full sample: (1) HA, (2) age, and (3) SCL-90R total score. The last two variables showed a direct correlation with the WAI-S total score, whereas a lower HA predicts a higher score at WAI-S (Table 2).

Predictors of the three subscales of WAI-SThe relation among variables at intake and the score in the three subscales of WAI-S has been explored with multiple linear regression methods (Goal; Task and Bond). As concerns the subscale “Goal” (items 1, 4, 8, 10, 11), no predictors have been identified. In the case of the subscales “Task” (items 2, 6, 12) and “Bond” (items 3, 5, 7, 9), the variables identified as predictors of WA are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

DiscussionAccording to literature, the WA strongly relates to psychotherapy process and outcome.40 Difficulties in building a good alliance with therapist were frequently found in subjects affected by BPD7: consequently, identification of WA predictors might be relevant in order to forecast which BPD patients are less responsive to psychotherapy and to provide tailor-made treatments for these subjects.

In our exploratory naturalistic study, forty-nine BPD subjects were assessed by age, sex, clinical severity, temperament, and character features before starting a module (40 sessions) of SB-APP,39 and WA was evaluated at end of the treatment.

Patients included in our study were required to rate their relationship with psychotherapist according to the following criteria: (1) level of agreement and mutual engagement in the goals of treatment, (2) level of agreement on methods leading to treatment goals, and (3) degree of mutual trust, acceptance and confidence. WA assessment was made at the end of the first SB-APP module in order to avoid interferences with the clinical work. Subjective perception of the relationship with the therapist was expected as stable after almost one year, while it is often changing or idealized at BPD treatment onset.

Previous studies showed that there's evidence that some specific psychosocial aspects are predictors of WA and psychotherapy outcome: quality of object relations,41 which characterizes the patient's lifelong pattern of relationships, recent interpersonal functioning,41 and mechanism of defences.42 In patients with BPD, both quality of objects relations30 and defensive level43 are poor.

Furthermore, TCI low score levels of SD19–21 were found in patients with severe personality disorders, and particularly in subjects with BPD. Subjects with a low SD suffer from poor autonomy and self-integration, and are described as immature, insecure, emotionally unstable, uncooperative and impulsive.22,37,44

On the contrary, little is still known about patients temperamental characteristics in order to predict WA and usefulness of psychotherapy. In anxious and depressed patients, the harm avoidance personality dimension scores correlate with maladaptive defensive scores,45 but explicit effects on WA are not described.

In the present study, three independent predictors of WA (client-rated) were identified through a multiple linear regression: (1) higher levels of HA (which is a temperamental trait of personality according to TCI) are predictive of difficulties in building a good WA; (2) on the contrary, higher levels of general psychopathology (SCL-90R total score) can lead to better WA; and (3) old age is overall related to better WA.

According to the first result of this study, WA seems to be related to one specific temperamental characteristic of patients with BPD (HA high levels) and not to the level of character weakness (SD low levels). This finding could represent a new perspective to evaluate psychotherapeutic process, also comparing BPD patients temperament characteristics with those of their parents.46

Temperament is a part of personality which is moderately heritable, stable throughout life, and mediated by neurotransmitter functioning in the central nervous system.21 HA reflects the efficiency of the behavioral inhibition system. Highly HA individuals are described as extremely careful, passive, rigid, depressed, and insecure.21 Among BPD outpatients included in the present study, those with higher HA scores showed a poorer WA at the end of the treatment (in all three subscales of the WAI-S). They could be identified as a subgroup of BPD subjects with higher temperamental liability for anxiety and avoidant attachment. This type of patients might show higher difficulties in building a therapeutic alliance, and a more severe impairment in interpersonal functioning.47 These data are also consistent with those that were found in Eating Disorders: higher HA predict dropout in the treatment of Anorexia Nervosa.7,17

Moreover, process investigations on time-limited psychodynamic psychotherapies have already suggested that WA is increased by therapist's technical interventions, when they are appropriately used.48 More in detail, transference interpretation, which strongly deals with therapeutic alliance, could be helpful or harmful according to patients personality functioning.48

Contrary to common expectations, patients with poor object relation49 and low WA50 prompted more from therapy with negative transference interpretation. More in detail, too many transference interpretations may decrease WA and may be detrimental with patients with higher levels of defensive functioning.51 On the contrary, higher levels of interpretations could increase WA in patients with a lower level of defensive functioning.51

Concerning patients with BPD, assessing different personality characteristics might be necessary in order to provide different technical intervention during psychodynamic psychotherapy. In order to preserve WA it is likely that patients with higher HA benefit from an intensive therapeutic work on their distorted relationships, including transference interpretation.

The SB-APP, which is a well structured treatment, aimed to safeguard WA and to prevent drop-out by an intensive psychotherapeutic strategy, seems more effective than unstructured psychological support in outpatients with BPD.39 Particularly BPD subjects who received SB-APP had a better outcome on impulsivity, suicidality, disturbed relationships and they showed a good WA,39 but the role of the temperamental traits on developing and maintaining the WA has not been investigated.

The second result of this study indicates that higher levels of general psychopathology (SCL-90R total score) can lead to better WA. As concerns SCL-90R scores at intake, patients with a greater level of psychiatric and psychosomatic symptoms appeared willing to build a better therapeutic relationship. Since the SCL-90R is a self-administered questionnaire, subjects who rated themselves as more severely disordered might also have had a higher awareness of their disease at intake (egodystonic functioning). Subjects with an egodystonic functioning are often more adherent to therapy and more likely to seek strong alliance with their therapist.

Finally, with respect to age, younger subjects tend to have a lower level of WA with the psychotherapist in our sample. This datum could not be surprising, since younger patients are often less motivated and tend to have a greater level of egosyntonia with their symptoms and behaviors.

This study has several limitations due to the particular complexity of the research area and to the naturalistic methodology. First of all, the size of the sample studied; secondly, the absence of a control group experiencing a different treatment strategy did not consent to investigate specific treatment effects; and lastly, the impossibility to compare results with a dropout group of subjects with BPD. Also the utilization of two self-administered questionnaires such as the TCI and the WAI-S could have biased the results: the subjects with higher HA could have a particular answering style to all types of self questionnaires.

ConclusionIf these preliminary results will be confirmed by further studies, more attention could be paid to the assessment of temperament dimensions prior to the planning psychological interventions for subjects with BPD. This kind of assessment (through TCI or similar instruments) could prove useful in order to identify at intake different subgroups of BPD outpatients needing specific technical interventions during psychodynamic psychotherapy to reinforce and to maintain the WA. Particularly in order to preserve WA it is likely that BPD patients with higher harm avoidance benefit of an intensive therapeutic work on their distorted relationships, including transference interpretation.48,49

Of course this data's interpretation at this moment still speculative, but these results highlighted the need of predictive factors to better tailor short term psychodynamic psychotherapy interventions in BPD in specialized or not specialized setting.52

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pierò A, et al. Dimensiones de la personalidad y alianza terapéutica en individuos con trastorno límite de la personalidad. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2013;6:17–25.