To determine the psychiatric hospitalizations of patients with severe schizophrenia before (standard treatment in mental health centres) and during treatment in a comprehensive, community-based, case-managed programme, as well as the role played by antipsychotic medication (oral or long-acting injectable).

MethodsObservational, mirror image study of ten years of follow-up and ten retrospectives (‘pre-treatment’: standard), of patients with severe schizophrenia in a community-based programme, with pharmacological and psychosocial integrated treatment and intensive case management (N = 344). Reasons for discharge from the programme and psychiatric hospital admissions (and whether they were involuntary) were recorded ten years before and during treatment, as well as the antipsychotic medication prescribed.

ResultsThe retention achieved in the programme was high: after 10 years only 12.2% of the patients were voluntary discharges vs 84.3% on previous standard treatment. The number of patients with hospital admissions, and number of admissions due to relapses decreased drastically after entering the programme (P < .0001), as well the involuntary admissions (P < .001). Being on long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication was related with these results (P < .0001).

ConclusionsTreatment of patients with severe schizophrenia in a comprehensive, community-based and case-managed programme achieved high retention rates, and was effective in drastically reducing psychiatric hospitalizations compared to the previous standard treatment in mental health units. Undergoing treatment with long-acting injectable antipsychotics was clearly linked to these outcomes.

Conocer los ingresos en una unidad hospitalaria de psiquiatría de pacientes con esquizofrenia grave antes (tratamiento estándar en CSM) y después de su incorporación a un programa comunitario, integral y con gestión de casos. También la influencia de la medicación antipsicótica (oral o inyectable de larga duración) en ello.

MétodoEstudio observacional, en espejo, de diez años de seguimiento y diez retrospectivos (“pretratamiento”: estándar), de pacientes con esquizofrenia grave en un programa comunitario, de tratamiento farmacológico y psicosocial integrado y con gestión de casos intensiva (N = 344). Se registraron los motivos de alta en el Programa y los ingresos hospitalarios (y si eran involuntarios) diez años antes y durante el tratamiento. También los antipsicóticos utilizados.

ResultadosLa retención conseguida en el Programa fue elevada: A los 10 años solo el 12,2% de los pacientes fueron altas voluntarias, frente a al 84,3% que lo habían sido en algún momento en el tratamiento estándar previo. El porcentaje de pacientes con ingresos hospitalarios y su número disminuyeron drásticamente tras la incorporación al Programa (P < ,0001), así como su involuntariedad (P < ,0001). El hecho de estar con medicación antipsicótica inyectable de larga duración se relacionó estos resultados (P < ,0001).

ConclusionesLa incorporación de pacientes con esquizofrenia grave a un programa integral, de base comunitaria y con gestión de casos intensiva consiguió una elevada retención en tratamiento, y fue efectivo para disminuir drásticamente las hospitalizaciones por recaídas, comparado con el tratamiento estándar previo en CSM. El tratamiento con antipsicóticos inyectables de larga duración se relacionó con estos resultados.

Adherence to treatment must be encouraged and continuity of care ensured to achieve clinical and rehabilitation intervention targets in people with severe schizophrenia. There are 2 community models of care for these patients: “case management (CM)” and “assertive community treatment (ACT)”. FACT is a more recent model that integrates CM and ACT, and its intensity depends on the patients’ needs.1–4 Case management has been defined as a way of coordinating, integrating, and allocating individualised care through continuous contact with one or more key professionals.2–4 Case management has demonstrated achievements in several areas, including reducing the severity, duration and number of hospitalisations, and treatment disruptions. However, its effectiveness and superiority over other models and standard treatment itself is still under debate.5–8 Reducing admissions to acute units for psychopathological decompensation, and ensuring that they are not involuntary, are basic clinical objectives and priorities in these programmes, and are part of the usual indicators of their effectiveness.7–11 Adherence to treatment is fundamental to achieving results, and improving it with psychosocial and pharmacological strategies remains a challenge.

Non-adherence to treatment hinders remission of symptoms and recovery in patients with schizophrenia, and is associated with serious clinical consequences such as relapse.12–14 The rate of non-adherence to treatment among people diagnosed with schizophrenia has been estimated at between 20% and 56%.15,16 Several factors may affect these patients’ adherence to treatment, including those related to treatment in general (community or hospital-centred, intensity, care provision, etc.) and to drugs specifically (lack of efficacy, side effects, frequency of administration, duration of treatment, etc.).17,18

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAI AP) can be considered an effective treatment strategy to improve adherence.19–21 The results from clinical trials comparing second-generation (2nd G) LAI AP with oral antipsychotics (OAPs) are not consistent, and are heavily influenced by study design biases.22–25 The superiority of LAI AP over OAPs in efficacy is most evident in mirror image and cohort studies. Overall, both clozapine and 2nd G LAI AP have demonstrated the highest relapse prevention rates in schizophrenia. The risk of re-hospitalisation is at least 20%–30% lower with 2nd G LAI AP than with the equivalent oral formulations.26–28

The present study sought to determine the admissions to a psychiatric inpatient unit of patients with severe schizophrenia before (standard treatment in mental health centres) and after their incorporation into a community-based programme, with integrated pharmacological and psychosocial treatment and intensive case management, for people with severe mental disorders, and the influence of antipsychotic medication (oral or long-acting injectable).

MethodOverall design. ProcedureAn observational, longitudinal, mirror image study of 10 years of treatment follow-up and 10 retrospective years (“pre-treatment”: outpatient standard in a mental health centre) of patients with severe schizophrenia (ICD 10: F-20) (clinical global impression - CGI-S 5 or more) in treatment in a comprehensive, community-integrated, intensive case management programme for persons with severe mental disorders (PSMD) in a comprehensive treatment centre (CTC).

Two parts: prospective, observational, open-label, non-randomised, from the start of treatment in the CTC and over 10 years of follow-up (January 2008–December 2017), and retrospective, 10 years prior to the start of treatment at the CTC (standard treatment in the mental health centre). Admissions to the psychiatric inpatient unit ([PIU] number, whether involuntary), the PSMD’s time in treatment and reasons for discharge, including deaths due to suicide and, finally, antipsychotics prescribed (1st or 2nd G; oral or long-acting intramuscular) were recorded.

PatientsA total of 344 patients were included (all those who started treatment in the CTC between January 2004, when it opened, and December 2007. All had previously been in treatment in non-specific mental health facilities). The mean age was 45.5 (standard deviation: 9.8) years (range 18–68 years; mode: 44); 63.7% were male and 36.3% female. All the patients (or their legal representatives, if applicable) signed their informed consent at the start of treatment in the CTC.

InterventionThe Severe Mental Disorders Programme (SMDP) of Mental Health Clinical Management Area-V of the Principality of Asturias Health Service-SESPA (Gijon) is based on the principles of community care with intensive case management, with a multidisciplinary intervention team. Patients are referred to the programme from the area's mental health centres or from the PIU. All patients must score CGI-S 5 or more. The programme is physically located in the Integral Treatment Centre, and incorporates all the basic services necessary for the comprehensive treatment of psychosis and especially schizophrenia, in addition to outpatient treatment with 24-h coverage, day care, outpatient care, and home care (ACT), always adapted to the needs of the patient and thus ensuring continuity of care throughout the therapeutic process.

The team comprises psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, auxiliary nursing care technicians, and administrative staff. The social work professionals from the referring mental health centres also participate, when required. There is a sub-team in the CTC for each of the referring mental health centres of the health area (4 in total) that comprises a psychiatrist and 2 specialist mental health nurses/case managers (intensive CM, 20 patients per nurse).

The programme is intensive and multicomponent and includes pharmacological treatment (with routine use of long-term injectables), psychological treatment (individual and group), cognitive rehabilitation, daily living, management skills and self-care training, psychoeducation, vocational rehabilitation, and support for independent living.

Data analysisDescriptive and inferential statistics were analysed. The χ2 test was used for qualitative variables and the student’s t-test for paired data for quantitative variables. The confidence interval was set at 95%. The R Development Core Team (version 3.4.1) was used to process the data.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias.

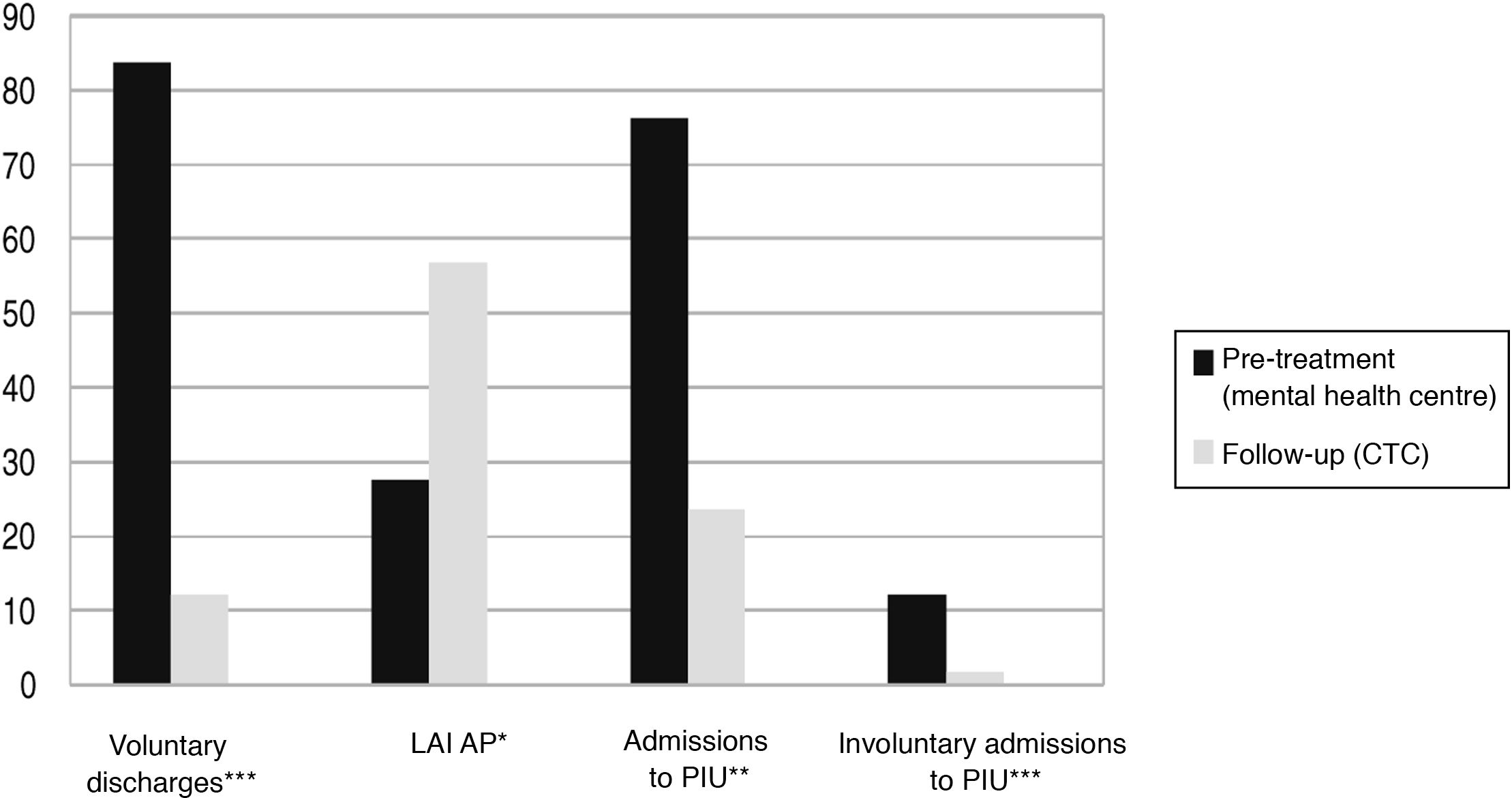

ResultsThe ICG-G at baseline was 5.9 (SD: .7). Before starting treatment in the CTC 84.3% of patients (n = 290) had at least one voluntary discharge from mental health treatment (treatment disruption). At 10 years 57.1% of the patients (197) were still in the programme (7.6% of them had moved to another health area, continuing on the PTMG there). A total of 19.3% (67) were medical discharges and 12.1% (42) were voluntary discharges. Forty patients died during follow-up (11.5%), 5 of them by suicide (1.4%).

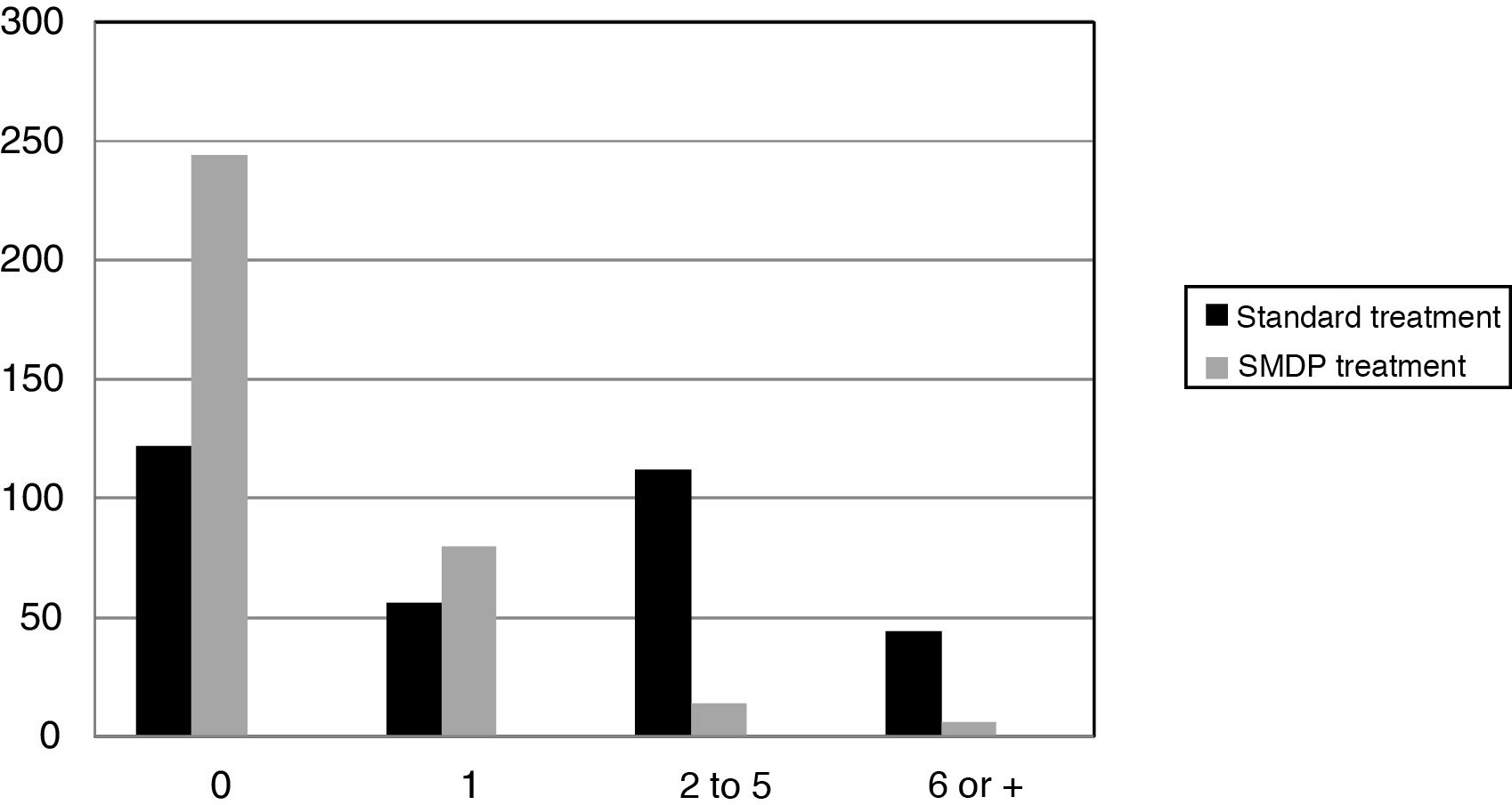

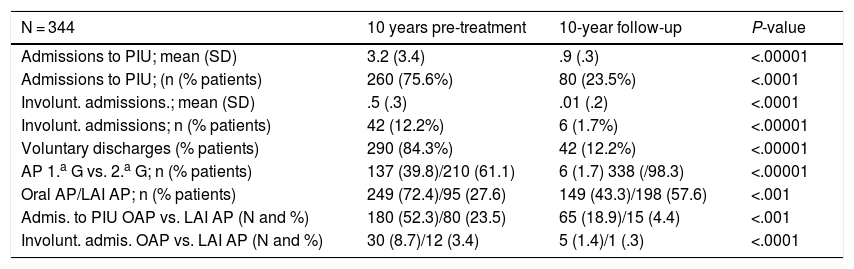

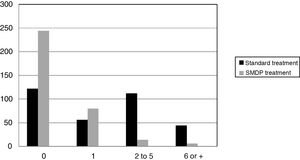

In the 10 years prior to starting treatment in the programme 75.6% of the patients (260) had had at least one admission to the PIU, with a mean of 3.2 (SD: 3.4) admissions, 12.2% were involuntary, with a mean of .5 (.3). During the 10 years of follow-up in the programme only 23.5% of patients (80) were admitted, reducing the mean to .9 (.3), and 1.7% were involuntary, with a mean of .01(.2) (Fig. 1). Both the changes in the number of admissions and whether they were voluntary were clearly statistically significant (P < .0001) (Table 1).

Admissions to PIU; antipsychotics used.

| N = 344 | 10 years pre-treatment | 10-year follow-up | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admissions to PIU; mean (SD) | 3.2 (3.4) | .9 (.3) | <.00001 |

| Admissions to PIU; (n (% patients) | 260 (75.6%) | 80 (23.5%) | <.0001 |

| Involunt. admissions.; mean (SD) | .5 (.3) | .01 (.2) | <.0001 |

| Involunt. admissions; n (% patients) | 42 (12.2%) | 6 (1.7%) | <.00001 |

| Voluntary discharges (% patients) | 290 (84.3%) | 42 (12.2%) | <.00001 |

| AP 1.a G vs. 2.a G; n (% patients) | 137 (39.8)/210 (61.1) | 6 (1.7) 338 (/98.3) | <.00001 |

| Oral AP/LAI AP; n (% patients) | 249 (72.4)/95 (27.6) | 149 (43.3)/198 (57.6) | <.001 |

| Admis. to PIU OAP vs. LAI AP (N and %) | 180 (52.3)/80 (23.5) | 65 (18.9)/15 (4.4) | <.001 |

| Involunt. admis. OAP vs. LAI AP (N and %) | 30 (8.7)/12 (3.4) | 5 (1.4)/1 (.3) | <.0001 |

LAI AP: Long-acting injectable antipsychotic; OAP: oral antipsychotic; SD: standard deviation; ns: not significant.

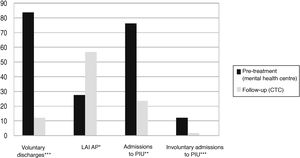

Prior to treatment in the programme 137 patients (39.8%) were on 1st G antipsychotics, and 61.1% (210) on 2nd G AP. During treatment 98.3% were switched to 2nd G AP (P < .0001). Their sex did not influence this change. On the other hand, before treatment in the programme, 72.4% (249) were on oral antipsychotics, and the majority were switched to long acting injectables (57.6% LAI AP vs. 43.3% oral; P < .001) during the programme. Again, sex did not influence this change (Fig. 2).

Regarding hospital admissions for decompensation, the fact that they were on 1st G and not 2nd G had an influence during follow-up (P < .001), although certainly the vast majority were on 2nd G AP. Admission to the PIU was more clearly related to treatment with oral AP, before contact with the programme (180 patients admitted with OAP vs. 80 with LAI AP; P < .001) and especially during the programme (65 with OAP vs. 15 with LAI AP; P < .0001). Also, being on oral APs made admissions more likely to be involuntary (30/12 pre-treatment vs. 5/1 on the programme; P < .0001) (Table 1).

The patients’ sex was not related to retention on the programme nor to the number of hospital admissions or whether they were involuntary. Neither was it related to the type of antipsychotic treatment.

Table 1 provides a summary of the study findings in terms of hospital admissions and type of antipsychotics used.

DiscussionEffectiveness of the community model of intensive case managementCase management as a model of community intervention for persons with SMD has undergone major changes in recent times. On the one hand, traditional models of CM appear outdated and are not widely used in clinical practice, as demonstrated by the expansion of the more recent models. On the other hand, the effectiveness of CM has been mainly restricted to very specific and non-homogeneous studies. More recent studies suggest that variables such as programme adherence may be associated with the effectiveness of CM.4,6

Several studies have been conducted to establish the effectiveness of these programmes, and overall have yielded inconclusive results, which may be related in part to practical and defining changes in case management models, and sometimes to a lack of rigour in the methodology followed. Therefore, it remains very important that the effectiveness of these models is determined.8

This study provides results regarding the effectiveness in terms of treatment adherence and hospital admissions of the case management approach of a programme for a specific population, patients with severe schizophrenia. The number of subjects studied with this profile is sufficiently large and they were also studied over a long period of time, unlike most of the research reviewed, and therefore we can refer to long-term treatment outcomes. Furthermore, the “mirror image” study design allows us to compare the standard treatment that the patients received up to the start of the programme (non-specific and non-intensive care from mental health centres) with that carried out in a “naturalistic” way, and suitable for external validity.

Adherence to treatmentSeveral data are striking in this study; the first is the high retention achieved, which is above that of most of the studies conducted in people with schizophrenia, and is the primary objective of the programme as it is a condition for achieving other objectives. This study allows us to measure retention in the treatment of people with severe schizophrenia,21–28 which in many translates as a lack of awareness of their illness and their discontinuing treatment.13,17 As it is based on routine clinical practice, it provides a perspective on the real-world outcomes of the intervention/programme delivered.13,25,29,30 It is well known that treatment disruption or inadequate treatment of patients with schizophrenia negatively influences the course of the illness, the intensity of symptoms, overall severity, and ultimately long-term outcomes, relapse and remission.13–17 Although it has been shown that people who receive case management are more likely to remain in contact with services and improve compliance with medication,5 no study in our country has evaluated this.

Admissions to a psychiatric hospital unitIn this study we chose a common variable in measuring the effectiveness of treatment in people with schizophrenia, namely hospital admissions, considering them an indicator of relapse/severe clinical decompensation. The few relapses requiring admission that we found are notably lower than those shown overall in previous studies with this patient profile, with a high risk of non-adherence to treatment and consequent relapses.31,32 It is also an achievement that most of these admissions were voluntary, and their number has significantly decreased compared to those prior to treatment on the programme, and this would probably indirectly indicate a better therapeutic relationship.

Given the high rates of non-adherence among patients with schizophrenia, and especially those with greater clinical severity and functional impairment, and their documented association with relapses and (re)hospitalisations,13–17,31,32 the findings of this study show how community-based programmes with integrated treatment and intensive case management are clearly effective compared to standard treatments from mental health centres as strategies to increase adherence and therefore reduce decompensations and hospital admissions.

Long acting injectable versus oral antipsychoticsAlthough it is clear that there are many interventions within the comprehensive and integrated approach that the programme delivers with patients (psychological, psycho-educational, health self-care, training/work promotion, etc.) and that influence its outcomes, we chose antipsychotic medication for this study because of its importance within the general treatment, its controversial rational and cost-effective use, and its more objective measurement. The current debate focusses particularly on the use of oral or long-acting injectable antipsychotics; the use of second-generation antipsychotics is generally recommended, although there is still no clear consensus on this.19–28

In this regard, meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing LAI AP with OAP (both 2nd G) have provided conflicting results.22,23,26,28 However, RCTs may not be the best strategy to assess the impact of LAI AP on adherence because of selective recruitment and improved adherence to oral treatment due to frequent visits and greater encouragement to continue with treatment.24,25 Studies comparing treatment periods with LAI AP versus OAP in the same patients may better reflect their real-world impact.22,24,27 A meta-analysis of 25 mirror image studies of LAI AP, with data from 5940 patients, demonstrated their superiority over OAP in preventing hospitalisation.27 Cohort studies show mixed results, but most report better outcomes for LAI AP than for OAP.25,28,29 In a meta-analysis including 58 studies, interventional and non-interventional, LAI AP were superior to OAP (both 2G) in reducing hospitalisations.26 Another meta-analysis of 16 RCTs comparing LAI AP with OAP showed that they were not significantly different in terms of treatment discontinuation due to adverse effects.33 However, there are only a few direct comparisons between the different LAI AP, and there appears to be no advantage of one over the other in effectiveness. In general, LAI AP seem to reduce relapses and (re)hospitalisations.21,33–35 Even naturalistic studies show high adherence and tolerability, with reduced admissions, at high doses in severe patients.36,37

This study provides relevant findings, given the number of patients, their severity, and the follow-up time, on the clear relationship between the use of LAI AP versus oral treatments in terms of achieving greater adherence and reducing hospital and involuntary admissions.38–41

Limitations of the studyThe limitations of the study are that it was designed as an open-label, non-randomised study under pragmatic, standard practice conditions. There was, therefore, no control group, and there was no active comparator during this investigation. All the patients in the study were classified as critically ill at the start of the study. Therefore, the results presented here cannot be generalised to non-severely ill populations.

ConclusionsThe incorporation of patients with severe schizophrenia into a community-based programme with a comprehensive approach, integrated pharmacological and psychosocial treatment, and intensive case management methodology, achieved high retention in treatment, which was helpful in drastically reducing admissions to the acute unit due to decompensation, and the number of involuntary admissions. Therefore, we can consider the programme highly clinically effective compared to standard pre-treatment in mental health centres in terms of treatment retention and hospital admissions for relapses. And the theoretical premises of community-based programmes with case management approaches seem to be fulfilled.

The fact that the patients were treated with long-acting injectable antipsychotics and not with oral antipsychotics clearly influenced these results. The few treatment disruptions also suggest good patient acceptance of both the programme in general and the injectable antipsychotic formulation in particular. The use of second-generation LAI AP should be considered much more routinely in these programmes given their clear association with reduced relapses and hospital admissions.42,43

The results, therefore, suggest that the intensity and multiplicity of care offered by a comprehensive, community-based, case-managed programme8,41 is more effective compared to standard treatment for patients with severe schizophrenia. The widespread implementation of such programmes, using long-term antipsychotic medication, given its association with improved adherence and reduced hospital admissions, should be considered the programme of choice for people with severe schizophrenia with clinical severity and functional impairment.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To Patricio Suárez Gil, Coordinator of the Biostatistics and Epidemiology Platform of the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias (ISPA), for his invaluable support in the statistical processing of the data.

Please cite this article as: Díaz-Fernández S, Frías-Ortiz DF, Fernández-Miranda JJ. Estudio en imagen en espejo (10 años de seguimiento y 10 de pretratamiento estándar) de ingresos hospitalarios de personas con esquizofrenia grave en un programa comunitario con gestión de casos. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2022;15:47–53.