According to most relevant guidelines, family psycho-educational interventions are considered to be one of the most effective psychosocial treatments for people with schizophrenia. The main outcome measure in controlled and randomised studies has been the prevention of relapses and admissions, and encouragement of compliance, although some questions remain about its applicability and results in clinical practice.

ObjectivesThe aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and implementation of a single family psychoeducational intervention in ‘real’ conditions for people diagnosed with schizophrenia.

MethodsA total of 88 families were randomised in two groups. The family intervention group received a 12months psychoeducational treatment, and the other group followed normal standard treatment. Assessments were made at baseline, at 12 and at 18months. The main outcome measure was hospitalisation, and secondary outcome measures were clinical condition (BPRS-E) and social disability (DAS-II).

ResultsA total of 71 patients finished the study (34 family intervention group and 37 control group). Patients who received family intervention reduced the risk of hospitalisation by 40% (p=.4018; 95%CI: 0.1833–0.6204). Symptomatology improved significantly at 12 months (p=.4018; 95%CI: 0.1833–0.6204), but not at 18 months (p=.4018; 95%CI: 0.1833–0.6204). Social disability was significantly reduced in the family intervention group at 12months and 18months.

ConclusionsFamily psychoeducational intervention reduces hospitalisation risk and improves clinical condition and social functioning of people with schizophrenia.

Numerosos estudios internacionales han mostrado la eficacia de las intervenciones familiares psicoeducativas en la prevención de recaídas de personas con esquizofrenia. Aún existe controversia sobre los resultados en variables de carácter clínico y funcional, así como su aplicabilidad en la práctica clínica habitual.

ObjetivosEvaluar la eficacia y la aplicabilidad de un programa de intervención unifamiliar, en comparación con el tratamiento habitual, en una muestra ambulatoria de pacientes con esquizofrenia, durante un periodo de 18meses.

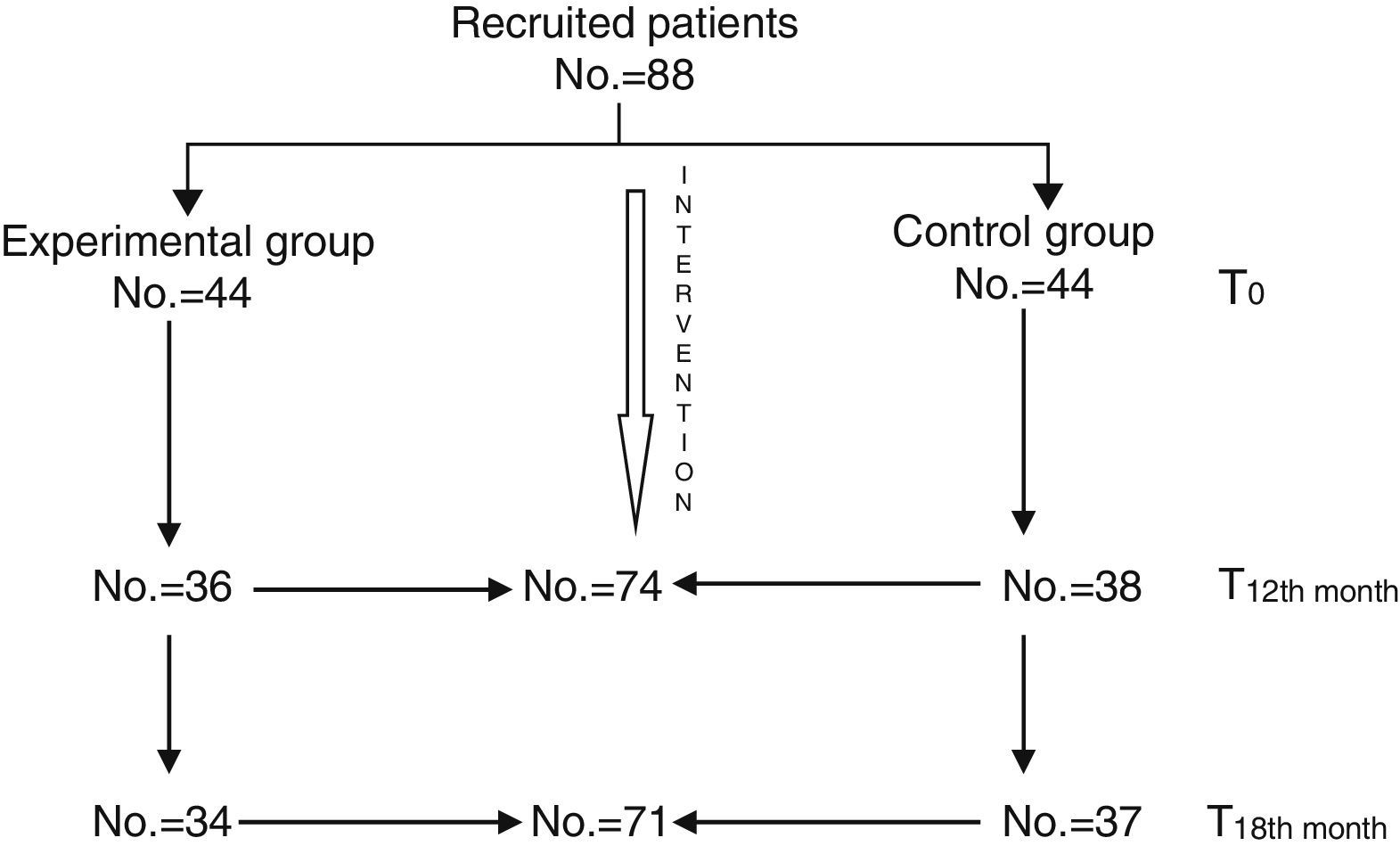

MetodologíaOchenta y ocho familias fueron aleatorizadas en 2grupos. El grupo experimental (n=44) recibió un programa de intervención familiar durante 12meses. El grupo control (n=44) mantuvo su tratamiento habitual. Se realizaron evaluaciones en el momento inicial, a los 12meses y a los 18meses. La medida principal de resultado fue el número de hospitalizaciones, y como medidas secundarias se utilizaron la gravedad de la sintomatología clínica (BPRS) y el funcionamiento social (DASII).

ResultadosDe los 88 pacientes reclutados, 74 completaron la evaluación a los 12meses y 71 la evaluación final a los 18meses. Los pacientes que siguieron intervención familiar redujeron un 40% el riesgo de hospitalización respecto a los pacientes que se mantuvieron con tratamiento habitual (p=0,4018; IC95%: 0,1833–0,6204). La sintomatología clínica mostró una mejoría significativa a los 12meses (p=0,0046) que dejó de serlo a los 18meses (p=0,4397). El nivel de discapacidad también se redujo de forma significativa, tanto a los 12 (p=0,0511) como a los 18 meses (p=0,0001) en el grupo tratado respecto al control.

ConclusionesLas intervenciones familiares psicoeducativas reducen el riesgo de hospitalización y mejoran el estado clínico y el funcionamiento social de las personas con esquizofrenia.

Family psychoeducational interventions (FPI) are one of the most common and scientifically supported psychosocial treatments for patients with severe mental disorders.1 During the last 2 decades, there have been several systematic reviews that demonstrated its efficacy,2–4 and they are recommended by the main Clinical Practice Guidelines and Consensus Documents for the treatment of schizophrenia.5–7

The conclusions of the last review conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration, which includes a total of 44 clinical trials carried out between 1988 and 2009 on 5142 participants, show that family psychoeducational intervention programmes, structured in sessions with a minimum duration of 3 months, reduce the short and long-term relapse and hospitalisation rate, and improve compliance. As to clinical symptoms, results are still controversial. Also, there is no consistency among obtained results regarding the improvement of social functioning, life quality or stigma.8

After more than 3 decades of research and accumulated experience on these interventions, there are still some essential aspects regarding their efficacy and effectiveness, which are yet to be clarified. Which are their essential elements? Which intervention methods or forms are more cost-effective? Are their effects long-lasting? Is it possible to replicate, in the everyday practice, the results obtained in controlled studies, conducted in academic institutions by highly trained and motivated personnel, without the overload of health care network devices? Finally, is it possible to obtain similar results if interventions are carried out by relatives or patients themselves?

Up to date, several controlled studies on the efficacy of psychoeducational interventions have been conducted in Spain, but generally with small samples, in specialised institutions or services, without further follow-up which would allow the assessment of the duration of the treatment effects. Our study intended to demonstrate the applicability and efficacy of a family intervention model within the health care network of several autonomous communities, embedded in the everyday work of 4 mental health teams, and developed by professionals who are not specialised in family therapy. The Falloon's single-family intervention model9 was the intervention model used for a group of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia with ambulatory treatment. Intervention results were assessed for both patients and relatives who participated in the programme. This paper shows the results obtained from patient intervention.

MethodologyStudy areaThe study was conducted in 4 centres from the public network of specialised mental health care services of several Spanish areas (Avilés, Barcelona, Cádiz and Málaga), with an assessment coordination centre of the University of Granada.

Therapists from the centres that participated in the study were given a training course, prior to the intervention, by an experienced therapist who later supervised intervention compliance with the model throughout the study.

All the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the participating centres.

Sample selectionPatients were selected in each centre by the corresponding therapists provided they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study. Upon complying with this condition, patients were referred to the investigating team, which verified compliance with inclusion and exclusion criteria and collected the informed consent from both patients and their relatives.

The randomisation process of patients to the experimental and control group was conducted in each centre. Recruited patients were assigned to the experimental or control groups at a 1:1 ratio until completion of the sample, which was estimated at 20–24 patients per centre. Finally, the distribution in each of the centres was the following: Avilés, 24 cases; Barcelona, 24 cases; Cádiz, 20 cases and Málaga, 20 cases.

Throughout the entire study, patients from the control and experimental groups continued receiving regular treatment and care provided by their corresponding reference team. Regular treatment involved pharmacological treatment follow-up and control by a psychiatrist and the nursing care team. The investigating team, which consisted of 2 therapists and a blind assessor, applied the family intervention programme and conducted assessments without participating in any decision regarding changes in the pharmacological treatment or hospitalisation indication, which were exclusively dealt with by the reference team.

Inclusion/exclusion criteriaStudy inclusion criteria included the following: more than 18 years of age; confirmed diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the DSM-IV criteria; live with, at least, one relative; understand and speak Spanish; no admission within the 6 months prior to the beginning of the study; treatment with antipsychotic drugs; and capacity to sign an informed consent. Study exclusion and/or withdrawal criteria included express willingness of patients or observation, by their regular therapist, of any severe upsetting event or any other cause which may render study continuation unadvisable. Each patient should register with a key relative with whom the patient lives and spends, at least, 8h per day, who should also agree to participate in the study.

Assessments and result measurementsThree assessments were conducted: at baseline (T0), 12 months (T12) and 18 months (T18) after the beginning of the intervention.

Result measurementsThe main result measurement was the number of hospitalisations that occurred during the 18 months of the study duration.

Other secondary result measurements were the following:

- (a)

Clinical symptoms, assessed using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, Expanded (BPRS-E)10 that has 24 items. Each item is rated using a scale from 1 to 7 points, where 1 is absent and 7 is extreme. Items may be grouped in 4 factors: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, agitation/hostility and depression/anxiety.

- (b)

Social functioning, assessed using the Spanish version of section 2 of the Disability Assessment Schedule (DAS) of the World Health Organisation.11 This schedule assesses aspects such as personal self-care, home and everyday activities, and the performance of family, social and working roles in a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means excellent functioning and 5 means extreme disability. At the end, it provides a global score of all items, which is obtained by adding up all scores and dividing this result by the number of applicable items.

Before the start of the study, there was a general training course for all therapists in charge of developing the programme. In this course, all the materials to be delivered to patients and their relatives were revised, and there were practical and role-playing exercises regarding communication skills and problem solving techniques. Therapists were given a manual of the programme with the key objectives to be developed in each of the sessions. The family intervention carried out for the group subject to treatment consisted of 24 sessions, which involved, at least, the patient and a key relative, apart from other direct relatives who wanted to participate in the sessions. Sessions lasted approximately 60min and were distributed into weekly sessions during the first quarter, fortnightly sessions during the 3 subsequent months and monthly sessions during the remaining 6 months. The total intervention period lasted 12 months. Sessions could take place at home or at the centre. In general, approximately half of the participants decided to have home sessions, and the other half decided to have sessions at the centre. The content of the treatment programme included 4 modules whose objectives were the following: basic information about the disease and its treatment; assessment of needs and family relations; training on communication skills; and problem facing and solving.

Statistical analysisIn order to analyse the results, we carried out a descriptive statistical analysis of the variables present in the model based on frequency distribution and basic summary measurements, such as mean and standard deviations. To establish comparisons between the time measurements of the study response variables and correct such measurements based on dependency, the mixed generalised linear model was used to establish the changes in symptoms through time. This model allowed us to analyse the variability within the group and among experimental and control groups, controlling the various variables that could affect results. Upon analysing the residue, we verified that the normal hypothesis was confirmed. The analysis of the number of hospitalisations was conducted using the Poisson regression, together with the goodness-of-fit test to verify that data fitted the model well, and the mean treatment marginal effect was calculated using the method of Bartus.12 Response measurements used in the Poisson regression were rate ratios together with the corresponding confidence intervals. All analyses were carried out using the STATA 10.113 statistical package.

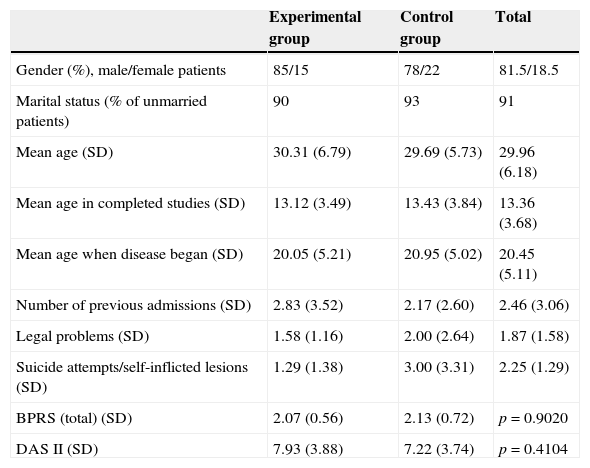

ResultsThe sample of patients consisted of a group of 88 patients (mean age: 29.9 years) with a mean disease progression of 10 years, mainly male (81.5%), unmarried (91%) patients with primary or middle education level. Mean admissions prior to the start of the study amounted to 2.83 in the experimental group and 2.17 in the control group.

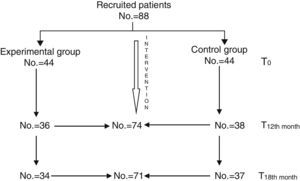

All patients continued with their prescribed pharmacological treatment. During the baseline assessment, mean global scores of the BPRS were included in the mild range, with a mean of 2.07 (sd=0.56) in the experimental group and 2.13 (sd=0.70) in the control group. The mean global score of the DAS 2 was 7.93 (sd=3.88) in the experimental group and 7.22 (sd=3.74) in the control group, so there were no significant differences between both groups (Table 1). The second assessment, conducted at 12 months, was completed by a total of 74 patients (36 from the experimental group and 38 from the control group). The last assessment, conducted at 18 months (6 months after finishing the intervention), was completed by a total of 71 patients (34 from the experimental group and 37 from the control group) (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of patients who participated in the study: experimental group and control group assessments.

| Experimental group | Control group | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%), male/female patients | 85/15 | 78/22 | 81.5/18.5 |

| Marital status (% of unmarried patients) | 90 | 93 | 91 |

| Mean age (SD) | 30.31 (6.79) | 29.69 (5.73) | 29.96 (6.18) |

| Mean age in completed studies (SD) | 13.12 (3.49) | 13.43 (3.84) | 13.36 (3.68) |

| Mean age when disease began (SD) | 20.05 (5.21) | 20.95 (5.02) | 20.45 (5.11) |

| Number of previous admissions (SD) | 2.83 (3.52) | 2.17 (2.60) | 2.46 (3.06) |

| Legal problems (SD) | 1.58 (1.16) | 2.00 (2.64) | 1.87 (1.58) |

| Suicide attempts/self-inflicted lesions (SD) | 1.29 (1.38) | 3.00 (3.31) | 2.25 (1.29) |

| BPRS (total) (SD) | 2.07 (0.56) | 2.13 (0.72) | p=0.9020 |

| DAS II (SD) | 7.93 (3.88) | 7.22 (3.74) | p=0.4104 |

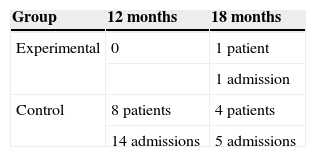

In the assessment conducted at 12 months, there were no hospitalisations in the experimental group, while in the control group 8 patients were admitted, at least, once. At 18 months, there was only one hospitalisation in the experimental group, while in the control group 4 patients were hospitalised once again. Upon analysing the differences observed among both groups regarding hospitalisation throughout the entire study period, we confirmed that, in the experimental group, only one patient was admitted (2.94%), while in the control group 8 patients (18.18%) were admitted 19 times (Table 2). Upon considering mean hospitalisations, the mean admission number in the experimental group was 0.033±0.1825, while the mean admission number in the control group was 0.463±1.206, which indicates that there were significant differences between both groups. To adjust these mean values according to the group and each of the variables studied at baseline, a Poisson multivariate analysis was conducted, as shown in the corresponding results table (Table 3).

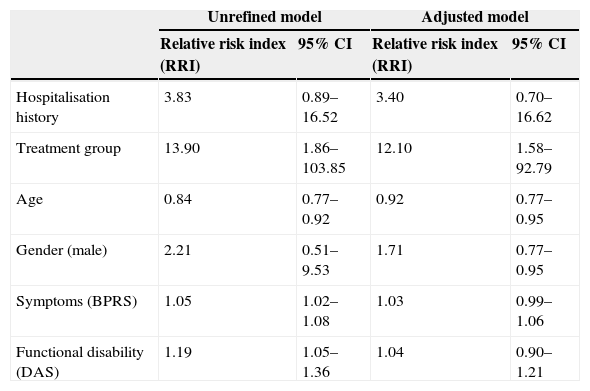

Multivariate analysis.

| Unrefined model | Adjusted model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk index (RRI) | 95% CI | Relative risk index (RRI) | 95% CI | |

| Hospitalisation history | 3.83 | 0.89–16.52 | 3.40 | 0.70–16.62 |

| Treatment group | 13.90 | 1.86–103.85 | 12.10 | 1.58–92.79 |

| Age | 0.84 | 0.77–0.92 | 0.92 | 0.77–0.95 |

| Gender (male) | 2.21 | 0.51–9.53 | 1.71 | 0.77–0.95 |

| Symptoms (BPRS) | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | 1.03 | 0.99–1.06 |

| Functional disability (DAS) | 1.19 | 1.05–1.36 | 1.04 | 0.90–1.21 |

In order to analyse the relative risk of hospitalisations, we prepared an unrefined model that conducted a bivariate analysis of each variable that may affect hospitalisation and an adjusted model that measured the effect of said variables controlled by the rest.

Hospitalisation history increased the risk of hospitalisation in 3.83 times, so it was necessary to control this variable in order to determine the relative risk of hospitalisation in each group.

The group that received FPI had a hospitalisation rate which was 13.9 times lower than that of the control group in the unadjusted model and 12.10 times lower in the adjusted model, with a point estimation of 0.4018 and a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.1833 to 0.6204, which means that the difference observed between these hospitalisation from the intervention group and the control group amounted to 40.18%.

Among socio-demographic variables, age showed to be inversely proportional: the hospitalisation rate decreases 0.84 times per one-year age increase, while gender only showed a hospitalisation tendency higher in men than in women, but it was not significant.

As to the severity of clinical symptoms, the hospitalisation rate increased 1.05 times per unit of increase in the BPRS, which is significant in the unrefined model, though this is not the case in the adjusted model.

This also happens with disability scores (DAS): the hospitalisation rate increases 1.19 times per unit of increase in the DAS, which is significant in the unrefined model, though this is not the case in the adjusted model, as it occurs with symptoms.

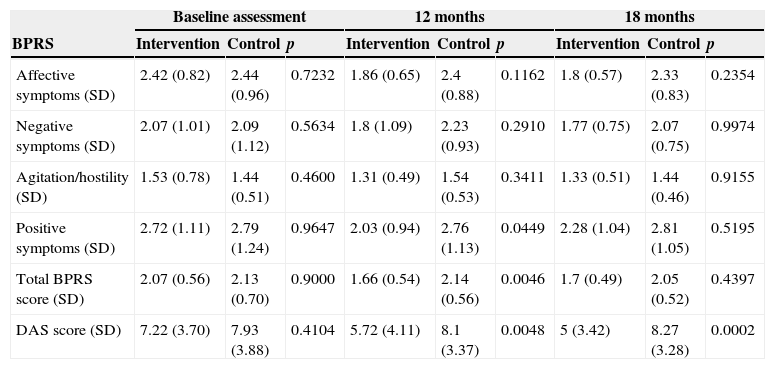

Family psychoeducational interventions and clinical symptomsTo assess the effectiveness of FPI on clinical symptoms, we compared the mean scores of the BPRS in the experimental group and the control group after finishing the intervention (12 months) and 6 months after finishing the treatment. In order to determine the differences within the group during the study, we assessed the differences between baseline values and closing values in each group.

When comparing both groups, the intervention group showed a significant improvement at 12 months (after finishing the treatment) regarding positive symptoms (p=0.0449) and the global score of the BPRS (p=0.0046) compared to the control group. At 18 months, though in the experimental group the global score of the BPRS continued to be lower than in the control group, the difference was not significant (p=0.1641). To control factors related to relatives and patients themselves, adjustments were made based on key relatives and clinical symptoms at baseline, respectively, and in both cases, the significant differences observed regarding BPRS scores between the experimental and the control group remained present (Table 4).

BPRS and DAS assessment at T0, T12 and T18 in the intervention group and in the control group.

| Baseline assessment | 12 months | 18 months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPRS | Intervention | Control | p | Intervention | Control | p | Intervention | Control | p |

| Affective symptoms (SD) | 2.42 (0.82) | 2.44 (0.96) | 0.7232 | 1.86 (0.65) | 2.4 (0.88) | 0.1162 | 1.8 (0.57) | 2.33 (0.83) | 0.2354 |

| Negative symptoms (SD) | 2.07 (1.01) | 2.09 (1.12) | 0.5634 | 1.8 (1.09) | 2.23 (0.93) | 0.2910 | 1.77 (0.75) | 2.07 (0.75) | 0.9974 |

| Agitation/hostility (SD) | 1.53 (0.78) | 1.44 (0.51) | 0.4600 | 1.31 (0.49) | 1.54 (0.53) | 0.3411 | 1.33 (0.51) | 1.44 (0.46) | 0.9155 |

| Positive symptoms (SD) | 2.72 (1.11) | 2.79 (1.24) | 0.9647 | 2.03 (0.94) | 2.76 (1.13) | 0.0449 | 2.28 (1.04) | 2.81 (1.05) | 0.5195 |

| Total BPRS score (SD) | 2.07 (0.56) | 2.13 (0.70) | 0.9000 | 1.66 (0.54) | 2.14 (0.56) | 0.0046 | 1.7 (0.49) | 2.05 (0.52) | 0.4397 |

| DAS score (SD) | 7.22 (3.70) | 7.93 (3.88) | 0.4104 | 5.72 (4.11) | 8.1 (3.37) | 0.0048 | 5 (3.42) | 8.27 (3.28) | 0.0002 |

Regarding the variability within the group through time, there was an improvement in the experimental group from baseline until month 12 as to affective symptoms (p=0.0168), positive symptoms (p=0.0038) and the global score of the BPRS (p=0.0018). In the final assessment, conducted 6 months after finishing the treatment, only a significant difference regarding baseline affective symptoms remained present (p=0.0071). In patients from the control group, there were no significant differences in any symptom assessment at neither 12 nor 18 months compared to baseline.

Family psychoeducational interventions and social functioningIn the same way as clinical symptoms, social functioning was assessed by comparing mean scores of the DAS from the experimental group and the control group at 12 and 18 months, and from within each group itself, from baseline to the end of the study.

The comparison between the experimental group and the control group, in the gross analysis, showed a significant difference in favour of the experimental group compared to the control group (5.72 vs 8.1; p=0.0046) at 12 months. This difference was higher at 18 months (5 vs 8.27; p=0.00001). To control factors related to relatives and patients themselves, adjustments were made based on key relatives and baseline, respectively, and, in both cases, the significant differences observed between both groups remained present.

Regarding variation within the group through time, a significant improvement was observed for the experimental group at 12 months (p=0.0035), which was even greater at 18 months (p=0.0001), compared to baseline. As to the control group, though an improvement was also observed (p=0.7961) at 12 months and 18 months (p=0.3292), it was not significant.

DiscussionThough the efficacy of FPIs has been widely demonstrated in international studies, this is the first multicentre, controlled and randomised study that has assessed the efficacy of a FPI model for the prevention of hospitalisation of schizophrenic patients, conducted under “natural” conditions, within the public health care framework of several Spanish communities.

The choice of hospitalisation as the main result measurement means that psychiatric admissions are to be considered one of the most consistent indicators in mental health research.14 Hospitalisation is a proxy for relapse with important consequences in human, social and economic terms, especially in patients with severe mental disorders.15

Previous studies conducted in our country have assessed the impact of FPIs on factors that mediate relapses, such as family load16,17 and emotions expressed by relatives,18–22 or have compared effectiveness among various FPI strategies.23–25 A controlled study conducted by Girón et al.26 in Spain, which included a smaller sample, determined that, after 24 months, there was a reduction in the number of relapse and hospitalisation cases, as well as an improvement in clinical symptoms and social functioning and employment.

Our results have definitely confirmed the efficacy of FPI in the prevention of hospitalisation of patients with schizophrenia 18 months after the intervention, since there were 12.10 times more admissions in the control group and 40.18% of hospitalisations were reduced in the group that received FPI, adjusting the model based on the total number of previous hospitalisations and other socio-demographic, clinical and functional variables at baseline. When comparing these results with those from other international studies, such as the Munich Psychosis Information Project Study,27 the percentage of patients admitted at 24 months amounted to 33% in the group with FPI and 54% in the control group. In our study, the percentage of admitted patients was 2.72% in the group with FPI and 18.18% in the group with regular treatment.

All of these studies are also consistent with the last review of the Cochrane Collaboration28 on the efficacy of FPIs for schizophrenia as to prevention of hospitalisation, which offers a 30% decrease of the risk of hospital re-admission in patients who receive FPI compared to those who receive regular treatment (n=206; RR: 0.71; confidence interval (CI): 0.56–0.89; number needed to treat (NNT): 5; CI: 4–13).

Regarding socio-demographic factors, age is inversely proportional to the risk of hospitalisation. Several studies have determined that, in younger patients or those who were young at their first admission, hospitalisations are more common.29,30 This may occur because, during the first stages, the disease is usually more unstable and there is a higher risk of relapse. Regarding gender, in our study, male patients had a higher risk of hospitalisation than female patients, but it was not significant. In previous studies conducted in Spain, hospitalisation rates for the group of patients with schizophrenic psychosis were higher in male patients than in female patients.31 In international studies, hospitalisation rates have also been higher in male patients than in female patients, with a 2:1 ratio for schizophrenia.32,33

Regarding the efficacy of FPI on the clinical status of patients, a significant improvement was observed in the post-intervention assessment (p=0.0046) for the control group, which continued up to month 18, but not in a significant manner (p=0.1641). This confirms the results from other studies, in which significant improvements regarding the clinical status of patients were observed after finishing FPI programmes.34–36 The observed improvement in affective symptoms was particularly significant, since it may be related to the way of facing the disease and a more positive attitude towards it.

The comparison between social functioning (DAS) results from the experimental and the control groups led to a significant difference in favour of the experimental group compared to the control group at 12 months (p=0.0046) and at 18 months (p=0.00001). When analysing the progression through time of the intervention group, a significant reduction in the disability global score is observed at both 12 and 18 months compared to baseline. The improvement in social functioning has also been observed in other studies and it is one of the most consistent pragmatic result measurements of FPI.37,38

The results found in this study about the impact of FPI in clinical symptoms and social functioning of patients match those found on another recent study, carried out in Catalonia, in which a clinical improvement after the intervention was also found, which tended to disappear over time, and significant improvement in social functioning was maintained 6 months after finishing the intervention.39

Lastly, another objective of the study was to assess the applicability and acceptance of a FPI model in the context of routine clinical practice. Although satisfactory results with the technique by therapists are not this study's goal, during the supervising sessions the establishment of a collaboration relationship between therapists, patients and relatives was observed, which facilitated the gathering of knowledge and skills for understanding the disease and the development of new patterns for coping and dealing with issues in the family and social context. The family group availability and acceptability to participate in treatment sessions, which have been considered a limitation in some studies40 for this type of interventions, have not been an obstacle for achieving high participation with a low withdrawal rate: 8/44 (18%).

LimitationsThe differences in the pharmacological treatment given to patients during the study may constitute a bias in the results. The naturalistic conditions of the study allowed the pharmacological treatment to be modified by the patient's referring therapist, both in the control and the experimental groups, so said bias affects the whole sample in the same way.

Hospitalisation as a main result measurement is consistent and reliable but it has its limitations, since it does not equal the relapse that can happen without hospitalisation. There can also be differences between the hospitalisation criteria of each centre.

Although supervisions were carried out by an external therapist, there could have been a difference in the application of the intervention due to the differences between the therapists of each centre.

ConclusionFPIs have proven useful in reducing the risk of hospitalisation in schizophrenic patients under ambulatory treatment.

In patients who have undergone an FPI, a significant improvement both in clinical symptoms and in social functioning has been observed, which in this last case has been maintained over time 6 months after the intervention was finalised.

Nonetheless, FPIs are still not accessible for most relatives and patients in standard clinical practice, which makes new studies necessary for achieving the generalisation of its use.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsAuthors state that the proceedings followed conformed to the ethical standards of the Responsible Committee on Human Experimentation and according to the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentialityAuthors state they have followed the protocols of their workplace about the data publication of patients and that all the patients included in the study have received enough information and have given their written informed consent to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentAuthors have obtained the informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in possession of the corresponding author.

FundingThe realisation of the study has been subsidised by the Ministry of Health, the Institute of Health Carlos III (Instituto de Salud Carlos III), Fund for Health Research (Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria) (PI021289).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Mayoral F, Berrozpe A, de la Higuera J, Martinez-Jambrina JJ, de Dios Luna J, Torres-Gonzalez F. Eficacia de un programa de intervención familiar en la prevención de hospitalización en pacientes esquizofrénicos. Un estudio multicéntrico, controlado y aleatorizado en España. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2015;8:83–91.