Delirium in palliative care patients is common and its diagnosis and treatment is a major challenge. Our objective was to perform a literature analysis in two phases on the recent scientific evidence (2007–2012) on the diagnosis and treatment of delirium in adults receiving palliative care. In phase 1 (descriptive studies and narrative reviews) 133 relevant articles were identified: 73 addressed the issue of delirium secondarily, and 60 articles as the main topic. However, only 4 prospective observational studies in which delirium was central were identified. Of 135 articles analysed in phase 2 (clinical trials or descriptive studies on treatment of delirium in palliative care patients), only 3 were about prevention or treatment: 2 retrospective studies and one clinical trial on multicomponent prevention in cancer patients. Much of the recent literature is related to reviews on studies conducted more than a decade ago and on patients different to those receiving palliative care. In conclusion, recent scientific evidence on delirium in palliative care is limited and suboptimal. Prospective studies are urgently needed that focus specifically on this highly vulnerable population.

El delírium en pacientes que reciben cuidados paliativos es frecuente y constituye un importante reto de diagnóstico y tratamiento. Nuestro objetivo fue realizar en 2 fases un análisis bibliométrico de la evidencia científica reciente (2007 a 2012) sobre diagnóstico y tratamiento del delírium en adultos en cuidados paliativos. En la fase 1 (estudios descriptivos y revisiones narrativas) se identificaron 133 artículos relevantes: 73 trataron el tema del delírium de forma secundaria y en 60 artículos como tema principal. Sin embargo, solo se identificaron 4 estudios observacionales prospectivos en los que el delírium fue central. De 135 artículos identificados en la fase 2 (ensayos clínicos o estudios descriptivos sobre tratamiento del delírium en pacientes paliativos), solo 3 fueron sobre prevención o tratamiento: 2 estudios retrospectivos y un ensayo clínico sobre prevención multicomponente en pacientes con cáncer. Gran parte de la literatura reciente corresponde a revisiones que hablan de estudios realizados hace más de una década en pacientes diferentes a los que reciben cuidados paliativos. En conclusión, la evidencia científica reciente sobre el delírium en cuidados paliativos es escasa y subóptima. Urgen estudios prospectivos que se enfoquen específicamente en esta población altamente vulnerable.

Delirium is an acute neuropsychiatric syndrome characterised by alterations in the level of alertness and cognitive functions that tend to fluctuate during the day; its cause is usually related to an underlying disease.1 Delirium is heterogeneous in its origin, course and resolution. In palliative care units, prevalence of delirium has been reported varying from 28% to 42% at the moment of admission and up to 88% in pre-death periods.1–3 In practice, delirium in palliative care patients is usually handled as with any other group; however, delirium has significant implications in this particular patient group and the way one deals with it involves difficulties not occurring in other hospital settings due to various factors:

- (a)

Palliative care patients are much more vulnerable to presenting delirium than other populations due to the baseline diagnoses (predominantly cancer or organ failures), to receiving multiple drugs and to the terminal nature of the disease.4,5

- (b)

There are different situations that can condition a sub-diagnosis of delirium in this group; among them is hypoactivity–whose diagnosis is generally more easily confused with other conditions–that is more prevalent.4–6 In addition, given that the patient is in the process of dying, the healthcare staff members themselves may have incorrect beliefs such as “many of the symptoms of delirium are to be expected”, “there's no need to treat them in this context” or “it's impossible to reverse”.

- (c)

It is always a good idea to assess whether there are modifiable variables that can affect remission or lessening of the intensity of the delirium; however, it should also be considered that refractory delirium can appear in this clinical context and it can determine the decision to use palliative sedation.7–13

- (d)

From the moment a patient is declared terminal or under palliative care, the possibility of communicating with the patient is essential, both for the family members and the healthcare team, because the medical team needs reliable information on the physical symptoms the patient presents to achieve better control of them. It is also necessary to attend to psychosocial variables that can become as relevant as the physical symptoms. Improper management of delirium in these patients can significantly modify the quality of death and can represent a factor of risk of psychiatric complications for their relatives.14,15

- (e)

In many cases, the episodes of delirium most probably present in the home. This can be an important cause of distress for the family member; if sufficient information has not been made available, the relative will not report these events to the treating physician and the episodes will consequently not be dealt with appropriately.13

- (f)

Attending a palliative patient is generally a complicated task for any health professional. Witnessing the deterioration and transition to death of a person is a significant cause of distress. It is no wonder that some treatment-related decisions are at times affected by the anguish that attending these matters causes the professional.

Diagnosis and treatment of delirium in palliative patients consequently constitutes a challenge. That is why it is necessary to research this subject in this specific patient group. The objective of this review was to analyse the evidence available in the last 5 years about delirium in adults receiving palliative care. Our interest was focused on answering the following questions:

- (1)

What types of studies on delirium in palliative care have been carried out in the last 5 years?

- (2)

What is the evidence that supports the efficacy of the treatments suggested by the literature to handle delirium in patients with advanced state of the disease?

- (3)

In which clinical domains has delirium treatment been found to have the greatest impact in this patient group?

The review was centred on adults in palliative care that presented delirium. We used systematic review techniques to lead the search in the scientific literature in English and Spanish. We performed a search of the studies in Medline/PubMed using combination of the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) search terms “delirium” or “confusion” and “palliative”. The search was restricted to studies published between January 2007 and April 2012. We then divided the analysis of the literature into 2 stages. In Stage 1, we included studies carried out on adults in palliative care that mentioned the dependent variable “delirium”. In Stage 2, we included studies that investigated some treatment for delirium (descriptive studies or clinical trials), which included 10 or more patients in each group and used standardised criteria for the diagnosis of delirium or validated instruments to measure its seriousness. A single reviewer (SS) assessed the eligibility of the studies identified in the search and extracted the data using a form of data collection predefined in the review protocol. When there was a doubt about article eligibility, a consensus was reached with the other authors of this review.

ResultsThe search yielded 164 articles, of which 133 were potentially relevant.

Stage 1To analyse the 133 relevant articles qualitatively, the articles were divided into 2 groups: (a) those in which the variable delirium was studied in an indirect or secondary manner and (b) those in which delirium was the main subject.

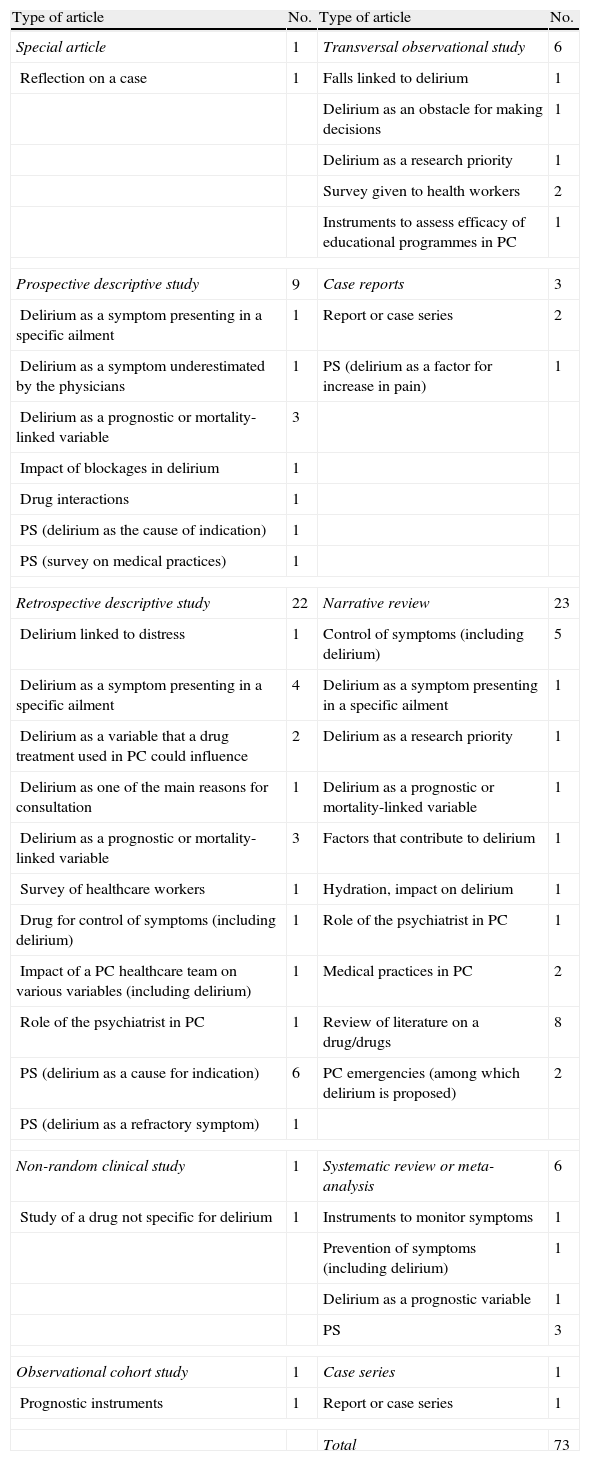

Variable delirium studied indirectly or secondarilyTable 1 presents a summary of the articles in which delirium was not the main variable. As you can see, the majority are retrospective studies and narrative reviews involving various subjects related to palliative care, including delirium, its detection and/or recommendations as to treatment. Analysing the data based on the most recurrent subjects, the main ones found were:

- •

Delirium as an indication for palliative sedation (n=9). In all the studies included here referring to delirium (refractory, agitated or hard to control), the condition was described as the 1st or 2nd reason–followed by dyspnoea – for initiating palliative sedation. The articles referring to this subject corresponded to 3 types:

- (a)

Retrospective studies, in which the frequency of using palliative sedation ranged from 31% to 82% of the cases.7–12

- (b)

Systematic reviews, which reported frequencies of using palliative sedation between 13.8 and 91.3%.13,16

- (c)

Prospective studies. One study17 covered the assessment of 42 patients that received palliative sedation. The main indications for palliative sedation were dyspnoea and delirium (57% of the cases). In another study,18 delirium was brought up as the main indication for intermittent sedation (81%) or continuous sedation (43%).

- (a)

- •

Delirium as a prognostic or mortality-linked variable (n=8). We classified the studies on this subject in the following manner:

- (a)

Retrospective studies. One of these sets the basis for creating the Delirium_PaP (D_PaP) scale,19 a version adapted from the Palliative Prognostic (PaP) Score.20,21 After assessing the information of 361 patients who were tested using the PaP score beforehand, delirium was added as an independent variable, which enabled better use of the instrument. Another study22 considers the presence of chronic delirium as a variable highly associated with mortality. However, we found another study23 where delirium proved not to be an important predictor variable.

- (b)

Prospective studies. One of these studies24 suggested the presence of delirium or chronic delirium as a variable associated with mortality. In another study, 4 prognostic instruments were compared: the PaP, D-PaP, Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI)25 and the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS).26,27 The D-PaP was found to have greater precision than the other instruments that did not include delirium as a predictive variable.28

- (c)

Reviews. The only systematic review in this category analysed the prospective studies on adults with a survival of 6 months or less; it found that anorexia, delirium and dyspnoea were the symptoms most associated with decrease in survival.29 We also found a narrative review that emphasised the variable delirium–among others–as a important primary factor of primary importance in the prognosis of patients with advanced solid tumours.30

- (a)

- •

Reviews on drug treatment of delirium (n=8). In this category we included narrative reviews on different drugs that could be indicated for delirium treatment in the context of palliative care.

- (a)

Reviews that included various drugs. We found narrative reviews in which common neuropsychiatric symptoms were covered–including delirium among them–associated with the use of some drugs in palliative care31 or specific sections on treating delírium.32,33

- (b)

Haloperidol. The evidence about the use of haloperidol–the most frequent treatment–in palliative medicine.34

- (c)

Olanzapine. The only article found provided an outline of the pharmacology and clinical evidence on the use of olanzapine in palliative care.35

- (d)

Trazodone. In this article, it was suggested that trazodone has unique pharmacological features, which could be an advantage in alleviating symptoms. It was proposed that the delirium not responding to neuroleptics responds well to this drug.36

- (e)

Propofol. We found 1 review on the use of this drug in palliative care. One of the indications reported for its use was refractory agitated delirium.37

- (f)

Dexmedetomidine. The objective of the article was to review the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dexmedetomidine and its potential use in the palliative care population, especially for treating delirium.38

- (a)

Type of articles studying delirium in a secondary manner.

| Type of article | No. | Type of article | No. |

| Special article | 1 | Transversal observational study | 6 |

| Reflection on a case | 1 | Falls linked to delirium | 1 |

| Delirium as an obstacle for making decisions | 1 | ||

| Delirium as a research priority | 1 | ||

| Survey given to health workers | 2 | ||

| Instruments to assess efficacy of educational programmes in PC | 1 | ||

| Prospective descriptive study | 9 | Case reports | 3 |

| Delirium as a symptom presenting in a specific ailment | 1 | Report or case series | 2 |

| Delirium as a symptom underestimated by the physicians | 1 | PS (delirium as a factor for increase in pain) | 1 |

| Delirium as a prognostic or mortality-linked variable | 3 | ||

| Impact of blockages in delirium | 1 | ||

| Drug interactions | 1 | ||

| PS (delirium as the cause of indication) | 1 | ||

| PS (survey on medical practices) | 1 | ||

| Retrospective descriptive study | 22 | Narrative review | 23 |

| Delirium linked to distress | 1 | Control of symptoms (including delirium) | 5 |

| Delirium as a symptom presenting in a specific ailment | 4 | Delirium as a symptom presenting in a specific ailment | 1 |

| Delirium as a variable that a drug treatment used in PC could influence | 2 | Delirium as a research priority | 1 |

| Delirium as one of the main reasons for consultation | 1 | Delirium as a prognostic or mortality-linked variable | 1 |

| Delirium as a prognostic or mortality-linked variable | 3 | Factors that contribute to delirium | 1 |

| Survey of healthcare workers | 1 | Hydration, impact on delirium | 1 |

| Drug for control of symptoms (including delirium) | 1 | Role of the psychiatrist in PC | 1 |

| Impact of a PC healthcare team on various variables (including delirium) | 1 | Medical practices in PC | 2 |

| Role of the psychiatrist in PC | 1 | Review of literature on a drug/drugs | 8 |

| PS (delirium as a cause for indication) | 6 | PC emergencies (among which delirium is proposed) | 2 |

| PS (delirium as a refractory symptom) | 1 | ||

| Non-random clinical study | 1 | Systematic review or meta-analysis | 6 |

| Study of a drug not specific for delirium | 1 | Instruments to monitor symptoms | 1 |

| Prevention of symptoms (including delirium) | 1 | ||

| Delirium as a prognostic variable | 1 | ||

| PS | 3 | ||

| Observational cohort study | 1 | Case series | 1 |

| Prognostic instruments | 1 | Report or case series | 1 |

| Total | 73 | ||

PC, palliative care; PS, palliative sedation.

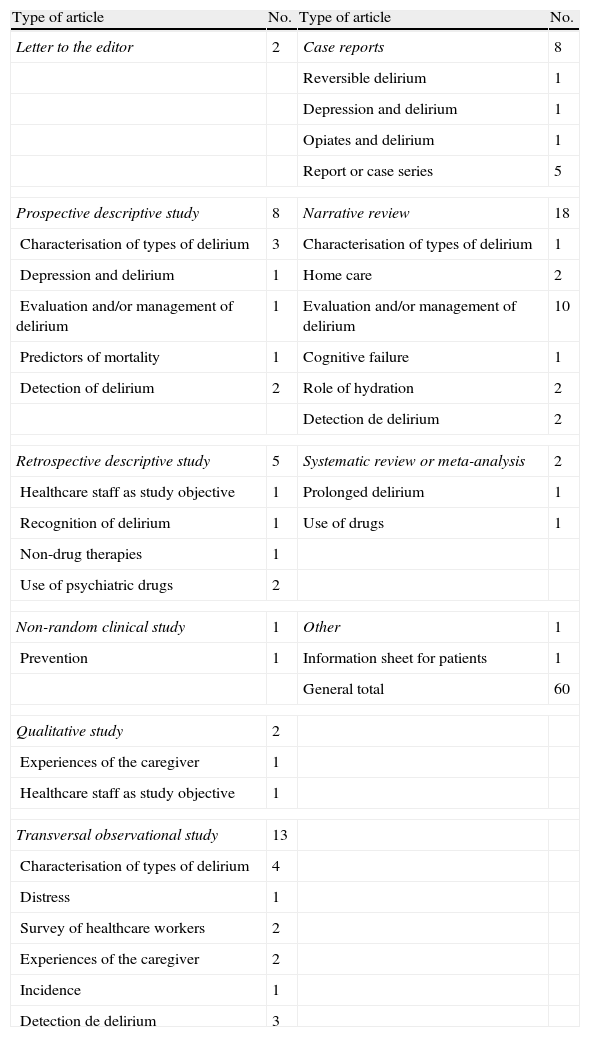

In Table 2 we present a summary of the articles in which delirium was the main variable studied. The narrative reviews again appear as the articles most published about this subject, followed by observational studies and prospective descriptive studies.

Articles featuring delirium in palliative patients as the main variable.

| Type of article | No. | Type of article | No. |

| Letter to the editor | 2 | Case reports | 8 |

| Reversible delirium | 1 | ||

| Depression and delirium | 1 | ||

| Opiates and delirium | 1 | ||

| Report or case series | 5 | ||

| Prospective descriptive study | 8 | Narrative review | 18 |

| Characterisation of types of delirium | 3 | Characterisation of types of delirium | 1 |

| Depression and delirium | 1 | Home care | 2 |

| Evaluation and/or management of delirium | 1 | Evaluation and/or management of delirium | 10 |

| Predictors of mortality | 1 | Cognitive failure | 1 |

| Detection of delirium | 2 | Role of hydration | 2 |

| Detection de delirium | 2 | ||

| Retrospective descriptive study | 5 | Systematic review or meta-analysis | 2 |

| Healthcare staff as study objective | 1 | Prolonged delirium | 1 |

| Recognition of delirium | 1 | Use of drugs | 1 |

| Non-drug therapies | 1 | ||

| Use of psychiatric drugs | 2 | ||

| Non-random clinical study | 1 | Other | 1 |

| Prevention | 1 | Information sheet for patients | 1 |

| General total | 60 | ||

| Qualitative study | 2 | ||

| Experiences of the caregiver | 1 | ||

| Healthcare staff as study objective | 1 | ||

| Transversal observational study | 13 | ||

| Characterisation of types of delirium | 4 | ||

| Distress | 1 | ||

| Survey of healthcare workers | 2 | ||

| Experiences of the caregiver | 2 | ||

| Incidence | 1 | ||

| Detection de delirium | 3 | ||

• Assessment and/or treatment of delirium (n=10). We classified the studies concerning this subject in the following manner:

- (a)

Narrative reviews. In this category we included trials with expert views,39–43 in which even proposals for assessment and treatment algorithms were presented.44 There were also reviews carried out under different guidelines, orienting the focus on nursing,45 drug treatment15,46 or drug-induced delirium.47

- (b)

Prospective study. We found 1 study5 in which the objective was determining the prevalence, detection and treatment of delirium in patients hospitalised with cancer. The research team independently identified the presence of delirium using the Delirium Rating Scale (DRS) and, if necessary, the psychiatrist prepared a diagnosis with the DSM-IV criteria. They found that the prevalence of delirium was high (46.9%) and that the most common subtype was the hypoactive (68.2%). The mortality rate was greater in the patients with delirium. Treatment was prescribed for delirium in 42.1% of the patients. Haloperidol was the drug most often used. The results of this study imply high delirium prevalence and low rates of detection and treatment.

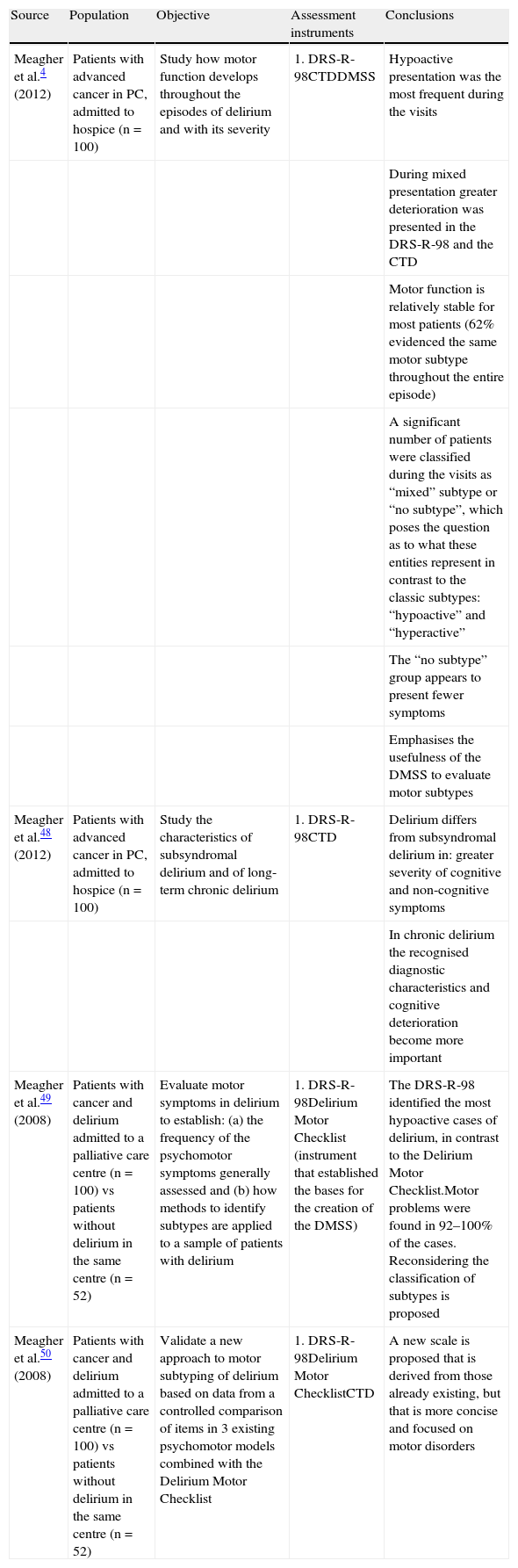

• Characterisation of types of delirium (n=8).

- (a)

Prospective studies (Table 3). These studies were carried out by basically the same work group. They studied the same cohort of patients and analysed it from various focuses.

Table 3.Prospectively designed studies featuring the characterisation of the types of delirium as the main subject.

Source Population Objective Assessment instruments Conclusions Meagher et al.4 (2012) Patients with advanced cancer in PC, admitted to hospice (n=100) Study how motor function develops throughout the episodes of delirium and with its severity 1. DRS-R-98CTDDMSS Hypoactive presentation was the most frequent during the visits During mixed presentation greater deterioration was presented in the DRS-R-98 and the CTD Motor function is relatively stable for most patients (62% evidenced the same motor subtype throughout the entire episode) A significant number of patients were classified during the visits as “mixed” subtype or “no subtype”, which poses the question as to what these entities represent in contrast to the classic subtypes: “hypoactive” and “hyperactive” The “no subtype” group appears to present fewer symptoms Emphasises the usefulness of the DMSS to evaluate motor subtypes Meagher et al.48 (2012) Patients with advanced cancer in PC, admitted to hospice (n=100) Study the characteristics of subsyndromal delirium and of long-term chronic delirium 1. DRS-R-98CTD Delirium differs from subsyndromal delirium in: greater severity of cognitive and non-cognitive symptoms In chronic delirium the recognised diagnostic characteristics and cognitive deterioration become more important Meagher et al.49 (2008) Patients with cancer and delirium admitted to a palliative care centre (n=100) vs patients without delirium in the same centre (n=52) Evaluate motor symptoms in delirium to establish: (a) the frequency of the psychomotor symptoms generally assessed and (b) how methods to identify subtypes are applied to a sample of patients with delirium 1. DRS-R-98Delirium Motor Checklist (instrument that established the bases for the creation of the DMSS) The DRS-R-98 identified the most hypoactive cases of delirium, in contrast to the Delirium Motor Checklist.Motor problems were found in 92–100% of the cases. Reconsidering the classification of subtypes is proposed Meagher et al.50 (2008) Patients with cancer and delirium admitted to a palliative care centre (n=100) vs patients without delirium in the same centre (n=52) Validate a new approach to motor subtyping of delirium based on data from a controlled comparison of items in 3 existing psychomotor models combined with the Delirium Motor Checklist 1. DRS-R-98Delirium Motor ChecklistCTD A new scale is proposed that is derived from those already existing, but that is more concise and focused on motor disorders - (b)

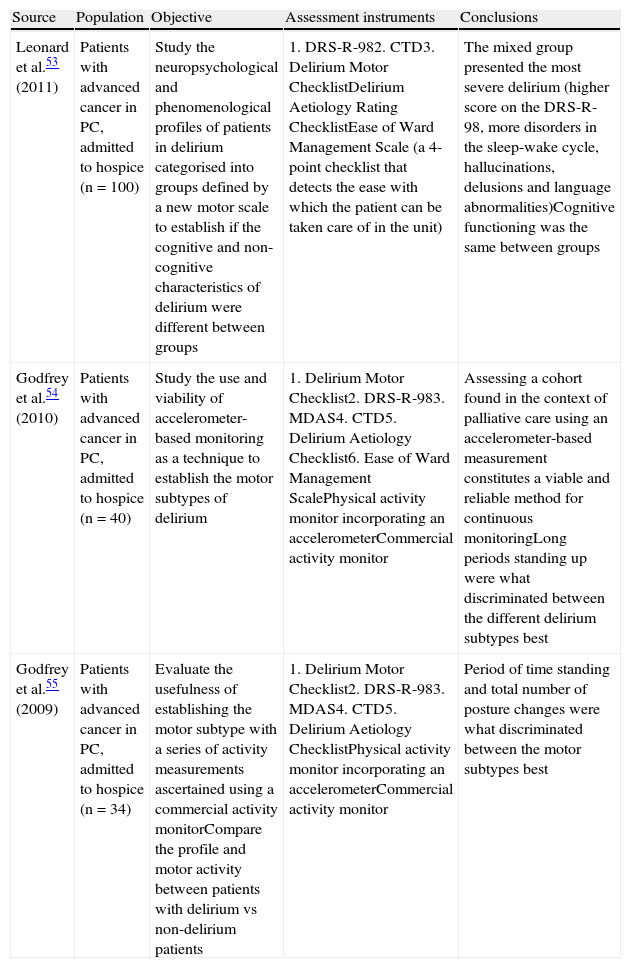

Transversal studies (Table 4). The last 2 studies belonged to the same work group mentioned in the previous sub-section and they basically took a subgroup of the same cohort of patients.

Table 4.Transversal studies featuring the delirium type characterisation as the main subject.

Source Population Objective Assessment instruments Conclusions Leonard et al.53 (2011) Patients with advanced cancer in PC, admitted to hospice (n=100) Study the neuropsychological and phenomenological profiles of patients in delirium categorised into groups defined by a new motor scale to establish if the cognitive and non-cognitive characteristics of delirium were different between groups 1. DRS-R-982. CTD3. Delirium Motor ChecklistDelirium Aetiology Rating ChecklistEase of Ward Management Scale (a 4-point checklist that detects the ease with which the patient can be taken care of in the unit) The mixed group presented the most severe delirium (higher score on the DRS-R-98, more disorders in the sleep-wake cycle, hallucinations, delusions and language abnormalities)Cognitive functioning was the same between groups Godfrey et al.54 (2010) Patients with advanced cancer in PC, admitted to hospice (n=40) Study the use and viability of accelerometer-based monitoring as a technique to establish the motor subtypes of delirium 1. Delirium Motor Checklist2. DRS-R-983. MDAS4. CTD5. Delirium Aetiology Checklist6. Ease of Ward Management ScalePhysical activity monitor incorporating an accelerometerCommercial activity monitor Assessing a cohort found in the context of palliative care using an accelerometer-based measurement constitutes a viable and reliable method for continuous monitoringLong periods standing up were what discriminated between the different delirium subtypes best Godfrey et al.55 (2009) Patients with advanced cancer in PC, admitted to hospice (n=34) Evaluate the usefulness of establishing the motor subtype with a series of activity measurements ascertained using a commercial activity monitorCompare the profile and motor activity between patients with delirium vs non-delirium patients 1. Delirium Motor Checklist2. DRS-R-983. MDAS4. CTD5. Delirium Aetiology ChecklistPhysical activity monitor incorporating an accelerometerCommercial activity monitor Period of time standing and total number of posture changes were what discriminated between the motor subtypes best - (c)

Narrative reviews. We were only able to identify a single article of this type, a review focused on geriatric patients with advanced cancer.58

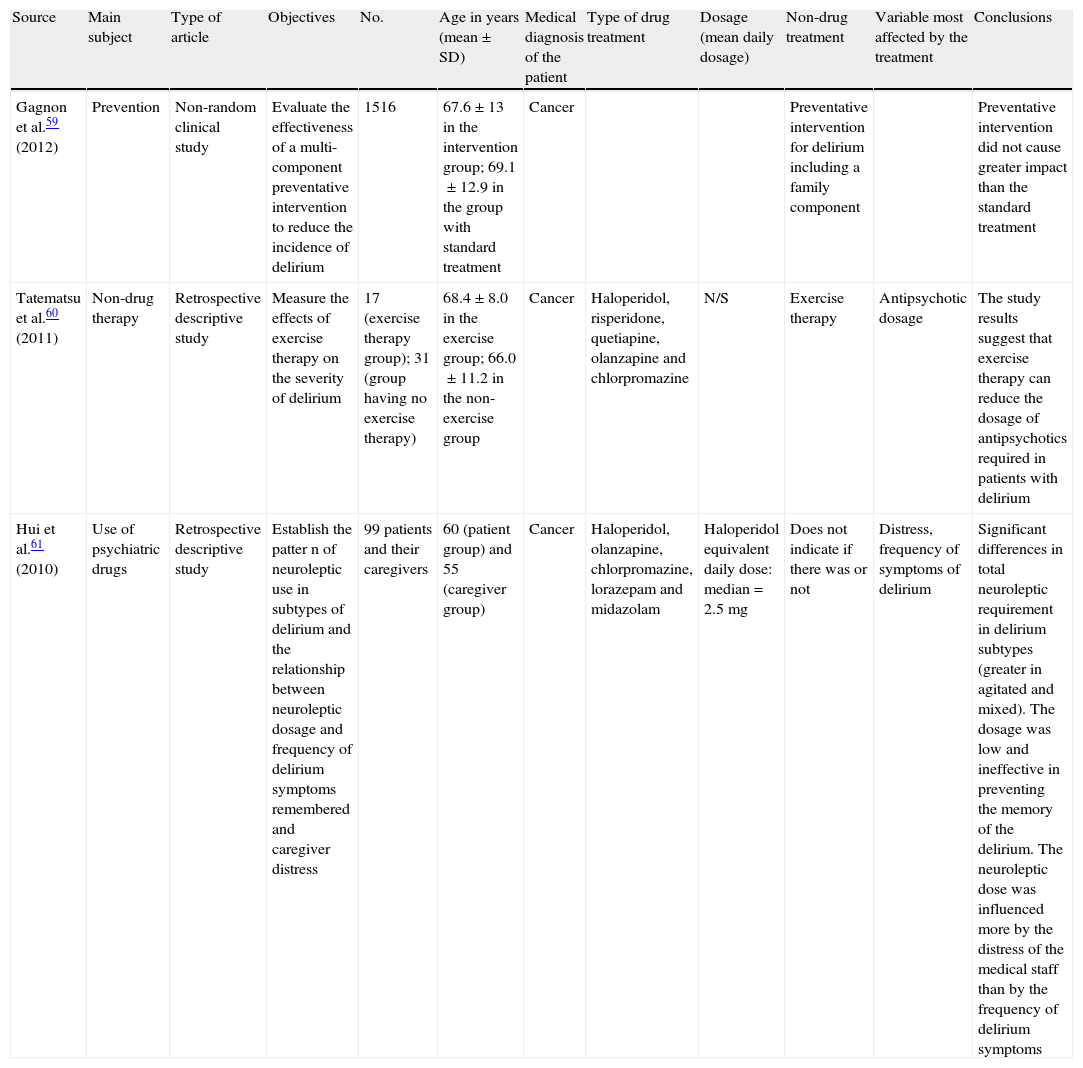

From the 135 articles we identified as potentially relevant, only 3 complied with the criteria for inclusion. Table 5 summarises the main findings of each article.

Articles assessing delirium treatment in palliative care.

| Source | Main subject | Type of article | Objectives | No. | Age in years (mean±SD) | Medical diagnosis of the patient | Type of drug treatment | Dosage (mean daily dosage) | Non-drug treatment | Variable most affected by the treatment | Conclusions |

| Gagnon et al.59 (2012) | Prevention | Non-random clinical study | Evaluate the effectiveness of a multi-component preventative intervention to reduce the incidence of delirium | 1516 | 67.6±13 in the intervention group; 69.1±12.9 in the group with standard treatment | Cancer | Preventative intervention for delirium including a family component | Preventative intervention did not cause greater impact than the standard treatment | |||

| Tatematsu et al.60 (2011) | Non-drug therapy | Retrospective descriptive study | Measure the effects of exercise therapy on the severity of delirium | 17 (exercise therapy group); 31 (group having no exercise therapy) | 68.4±8.0 in the exercise group; 66.0±11.2 in the non-exercise group | Cancer | Haloperidol, risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine and chlorpromazine | N/S | Exercise therapy | Antipsychotic dosage | The study results suggest that exercise therapy can reduce the dosage of antipsychotics required in patients with delirium |

| Hui et al.61 (2010) | Use of psychiatric drugs | Retrospective descriptive study | Establish the patter n of neuroleptic use in subtypes of delirium and the relationship between neuroleptic dosage and frequency of delirium symptoms remembered and caregiver distress | 99 patients and their caregivers | 60 (patient group) and 55 (caregiver group) | Cancer | Haloperidol, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, lorazepam and midazolam | Haloperidol equivalent daily dose: median=2.5mg | Does not indicate if there was or not | Distress, frequency of symptoms of delirium | Significant differences in total neuroleptic requirement in delirium subtypes (greater in agitated and mixed). The dosage was low and ineffective in preventing the memory of the delirium. The neuroleptic dose was influenced more by the distress of the medical staff than by the frequency of delirium symptoms |

The article by Gagnon et al.59 is the only study in which the variable delirium was the main one. Specifically, they focused on studying the efficacy of a multi-component preventative intervention to reduce the incidence of delirium. This intervention consisted of aiding the medical team and relatives so that they were more in touch with the symptoms of delirium and of providing recommendations to avoid confusion. No differences were found between the preventative intervention and the standard treatment. The strongest risk factor for developing delirium was having had a previous presentation of the condition. A third of the patients assessed did not experience any symptoms of delirium before demise.

The objective of Tatematsu et al.60 was measuring the effects of exercise therapy on the severity of delirium to determine if such therapy represented a viable and useful strategy of intervention. The study results suggest that exercise therapy can lower the dose of antipsychotic drugs required in patients with delirium. However, the study has many limitations, including the following: (a) retrospective design, (b) group assignment was not random, (c) effectiveness was assessed indirectly (through the use of antipsychotics), (d) the exercise was prescribed before the delirium occurred, (e) no information is given on the amount of exercise that could have an effect on delirium, and (f) the size of the sample was small.

In a retrospective study, Hui et al.61 attempted to determine the pattern of neuroleptic use for the subtypes of delirium in patients with advanced cancer and the relationship between neuroleptic dose and frequency of delirium symptoms remembered, as well as caregiver distress. They found significant differences in the total neuroleptic need in the subtypes of delirium (greater in agitated and mixed types). The dosages were generally low and not very effective in preventing the memory of the delirium, and it was emphasised that such dosages were influenced more by the distress of the medical staff that by the frequency of the delirium symptoms.

DiscussionThe objective of this review was to present the evidence available from the last 5 years with respect to delirium in adult patients receiving palliative care. In the 1st stage, we sought to provide a general view of the main subjects that have been raised in these last years. For Stage 2, we focused on specifically reviewing the articles approached delirium as the main variable and in which the efficacy and/or safety of some treatment was assessed.

When delirium was treated as a secondary variable, it was approached indirectly as an indication for palliative sedation as a prognostic variable linked to mortality. Likewise, suggestions for drug treatments in palliative care were presented in which treating delirium appeared as a specific section.

When delirium was analysed as the main variable, we found ourselves predominantly with narrative reviews prepared by experts. There were also an important number of studies referring to the characterisation of the types of delirium. Almost all of these were carried out by the same work group using the same cohort of patients. Their studies responded to the fact that, although classically a typology was proposed based on psychomotor activity (hyperactive, hypoactive and mixed delirium), it seems that in many studies it has been difficult to establish the true nature of the psychomotor abnormality due to its fluctuation and the possible confounding effects of the drugs used to treat delirium.

In the 2nd stage of our review, only 3 articles complied with the inclusion criteria. A multi-component preventative intervention was found not to influence the appearance of delirium.59 Exercise therapy was proposed as a possible intervention that could contribute to delirium treatment.60 Patients with agitated and mixed delirium were prescribed higher dosages of neuroleptics, although these dosages depended on the distress arising in the medical staff and not due to the frequency or the intensity of the symptoms.61

Level III evidence was the general characteristic of the body of knowledge consisting of the articles presented here, based on the 1996 North of England Evidence-Based Guideline Development Project. That is, the lack of studies of high scientific quality was the common characteristic in the matter of delirium in patients receiving palliative care. Our findings agree with a review of the literature with respect to various subjects involving delirium in palliative care, where it is concluded that there are no rigorous studies that examine factors of risk, assessment, management and outcomes of delirium.40 Consequently, the need for information applicable specifically to this group of patients is emphasised.40

There is a need for evidence-based recommendations for drug treatment of delirium in palliative patients. Knowledge on drug treatment for delirium derived from clinical trials is limited,46 so the articles on narrative review are generally based on the “best practices” currently described. In general, neuroleptic drugs are proposed as the first-line short-term agents to aliviate the disorders in perception or the agitation while reversible causes are explored and treated. This recommendation is partially supported by some clinical trials and by fundamentals in neuropharmacology.39 Due to this, dosage recommendations are normally based on clinical experience derived from case series. However, there are beginning to be reports on the efficacy of the atypical antipsychotics, which achieve that of haloperidol, but with fewer extrapyramidal effects.62 Likewise, using other emerging drugs (such as methylphenidate, modafinil, melatonin and cholinesterase inhibitors, among others) has been suggested.

Delirium usually causes significant distress in both patients and their relatives.63–65 It has been found that up to 74% of the patients that recover from delirium have a clear memory of the episode and, as a consequence, greater distress (post-traumatic stress).66 In addition, caregivers of patients with delirium have 12 times more risk of presenting generalised anxiety disorder than those who do not take care of patients in delirium, a phenomenon known as “perceived stress”.66 There are specific recommendations to help caregivers to lower the anxiety related to the presentation of this clinical entity.66 These suggestions are related to respect for the patient and constant communication between the heath team and the family. However, the strategies of detection, prevention and management are insufficient.67–70 This is because although there are recent advances in the use of validated instruments to detect and diagnose delirium as well as to monitor treatment,71–73 it seems that objective application and interpretation of these instruments still depends on the assessor in many cases.

Unfortunately, very little of the scientific evidence on prevention or treatment has been derived directly from the group of patients that receive palliative care. That is why it is almost impossible to propose here diagnosis or treatment algorithms that are directly applicable to this vulnerable group and from which predictable clinical responses can consequently be obtained.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, this systematic review of the recent scientific literature reveals the need for high-quality scientific studies that make it possible to report on current practice and effectiveness in the management of delirium in patients under palliative care. We have emphasised here that the application of the scientific evidence generated in other patient groups is not in all cases applicable to the group of individuals with a terminal disease receiving palliative care. Consequently, a need exists for proposing a new scientific agenda that has this vulnerable population as study subjects.

Conflict of interestsThis Project received financial support from the foundation Fundación INBURSA, A.C.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Román S, Beltrán Zavala C, Lara Solares A, Chiquete E. Delírium en adultos que reciben cuidados paliativos: revisión de la literatura con un enfoque sistemático. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2014;7:48–58.