The study aims to illustrate the impact of Spanish research in clinical decision making. To this end, we analysed the characteristics of the most significant Spanish publications cited in clinical practice guidelines (CPG) on mental health.

Material and methodsWe conducted a descriptive qualitative study on the characteristics of ten articles cited in Spanish CPG on mental health, and selected for their “scientific quality”. We analysed the content of the articles on the basis of the following characteristics: topics, study design, research centres, scientific and practical relevance, type of funding, and area or influence of the reference to the content of the guidelines.

ResultsAmong the noteworthy studies, some basic science studies, which have examined the establishment of genetic associations in the pathogenesis of mental illness are included, and others on the effectiveness of educational interventions. The content of those latter had more influence on the GPC, because they were cited in the summary of the scientific evidence or in the recommendations. Some of the outstanding features in the selected articles are the sophisticated designs (experimental or analytical), and the number of study centres, especially in international collaborations. Debate or refutation of previous findings on controversial issues may have also contributed to the extensive citation of work.

ConclusionsThe inclusion of studies in the CPG is not a sufficient condition of “quality”, but their description can be instructive for the design of future research or publications.

Se quiere ilustrar el impacto de la investigación española en la toma de decisiones clínicas y sanitarias. Con este fin se formula la cuestión de cómo son las publicaciones científicas españolas más citadas en las guías de práctica clínica (GPC) en salud mental.

Material y métodoSe plantea un estudio de tipo descriptivo-cualitativo sobre las características de 10 artículos originales españoles citados en la GPC sobre trastornos mentales y seleccionados por su «calidad científica». Se analizó el contenido de los artículos según las características siguientes: tema, diseño, centros de investigación, relevancia científica y práctica, tipo de entidad financiadora y posición de la referencia o influencia del contenido en la GPC.

ResultadosEntre los estudios que han alcanzado notoriedad figuran algunos de ciencia básica que examinan el establecimiento de asociaciones genéticas en la patogenia de las enfermedades mentales y otros sobre la eficacia de las intervenciones educativas. El contenido de estos últimos es el que más influencia ha tenido en la GPC, citándose en el resumen de la evidencia o en recomendaciones. Algunas de las características que destacan en los artículos seleccionados son los diseños sofisticados (experimentales o analíticos) y el carácter multicéntrico, especialmente con colaboraciones internacionales. La confirmación o refutación de hallazgos previos en temas polémicos puede haber igualmente contribuido a la amplia citación de los trabajos.

ConclusionesLa inclusión de estudios en las GPC no es una condición de «calidad» suficiente pero, sin embargo, su descripción puede ser ilustrativa para el diseño de futuras líneas de investigación o publicación.

It is a well-known fact that in the present health and science world great value is given to what has been called “scientific quality”, basically using bibliometric indicators. Of these there is a wide assortment, bibliometrics reaching a high level of refinement in its valuations. At present, the number of citations that each article receives is one of its basic indexes when spreading the echo that the study receives from other researchers. However, the relevance of scientific research should, in ideal conditions, also be assessed in other dimensions. Among these are the different types of scientific and social impact that a given investigation has caused.1 One of the most notable impacts is the effect that the study in question exercises on decisions by the corresponding health collective. The diffusion of an article can be measured with fairly direct and quantitative criteria, such as the number of citations received, while the impact on making decisions is more subtle and complex and, normally, less subject to direct measurement.2 One indirect way used to obtain an initial approximation of the influence of a specific work on decision-making is to analyse whether or not it has been included in the corresponding clinical practice guidelines (CPG), in how many and in which of them and in what sense and proportion its content has been incorporated into them.3,4

In the project “Social Impact of Research” [ISOR is the Catalan acronym], developed by the “Agency for Information, Assessment and Quality in Health” [AIAQS], various studies are being carried out on the social impact of biomedical research and its assessment. In one of them, the impact of Spanish research on mental health has been analysed by means of the use that the main Spanish CPG have made of Spanish studies.5 In this study, it was calculated that Spanish research in the CPG recommended by the National Health System represented 19% of all the references. Of these publications, the bibliometric indicators make it possible to select a group of studies that have reached a high number of citations and impact at the international level.

This article presents part of this study in which a group of Spanish scientific publications considered of “scientific quality” and referenced in Spanish CPG on mental health is analysed. The objective is to show what a few fundamental characteristics of this group of elite Spanish studies on mental health are. This can represent an illustration of what research in the country with the greatest influence in clinical and health decision-making is like. In addition, and even more importantly, the information can provide an orientation to calibrate the relevance that other studies in the same field might have in future.

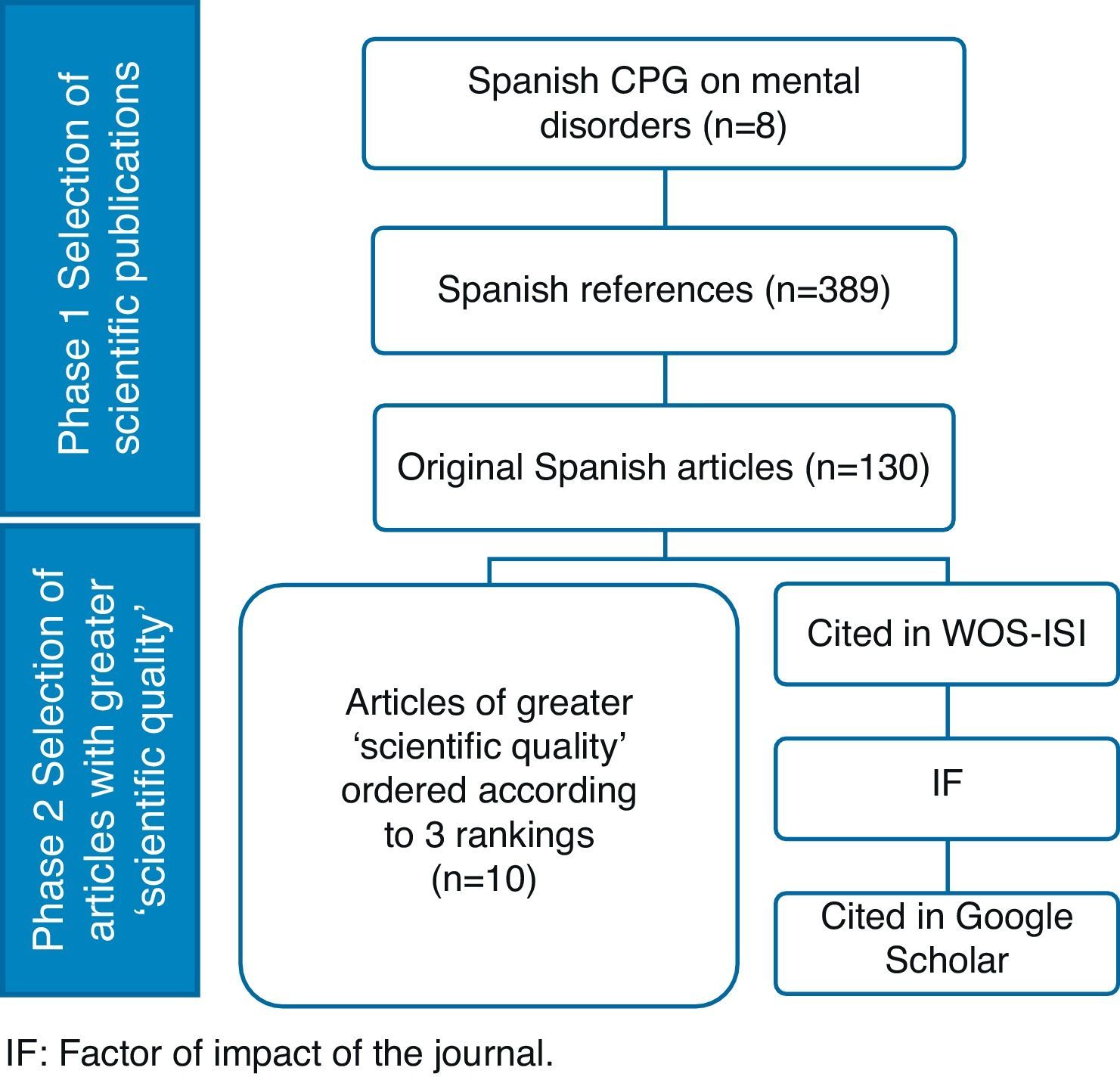

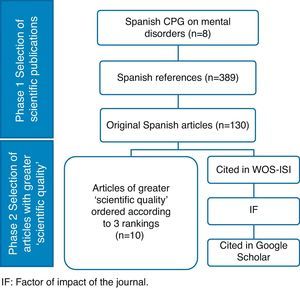

Materials and methodsThis was a qualitative study descriptive of the characteristics of the scientific publications of greatest “scientific quality” in bibliometric terms. The selection of the sample was carried out in 2 phases: (a) Phase 1: selection of Spanish scientific publications with potential impact on decision-making, and (b) Phase 2: selection or original Spanish articles considered of greatest “scientific quality” or bibliometric excellence included in the publications identified in Phase 1 (Fig. 1).

For the choice of publications in Phase 1, the sources of data selected in June 2011 were the CPG about mental disorders published in Spain in Spanish and indexed in the register of GuíaSalud (HealthGuide). This was chosen because it has a wide representation of the current most recommended practices in this field, judging by the criteria of quality that are established for its selection. In addition, the CPG had to be published in the format of GuíaSalud itself (to obtain guidelines with the most homogeneous format as possible). Guidelines that had not passed through this filter were ignored.

A selection was made of the bibliographic references included in each CPG that, as a minimum, the affiliation of 1 of the authors was located in Spain, independently of the order of the authors. The references were taken manually from the CPG between July and September 2011. These were entered into a specific database for the study, standardising and completing them through searches in the most common databases (Science Citation Index, PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar) that have been shown to contain different numbers of citations.6

For the selection of the original Spanish articles in Phase 2, these were classified and ranked according to 3 criteria:

- -

Criteria 1: Number of citations obtained according to the WOS-ISI database from its publication through September 2011.

- -

Criteria 2: Factor of impact of the journal in the year of publication.

- -

Criteria 3: Number of citations obtained according to the Google Scholar database, an alternate search engine with greater scope than purely scientific considerations.

The 10 best articles in each ranking were compared. After that, articles that were included in at least 2 of the 3 classifications were selected.

The original articles of the sample selected were then obtained. Two of the authors analysed the content of the articles and gathered a few indicators that showed a profile of the studies based on their subject, study design, research centres, scientific and practical relevance, type of funding body and position of the reference or influence of its content in the CPG according to the position of the reference. This final indicator served to analyse where the references were located within the CPG and, consequently, to what degree they contributed to the recommendations given in the CPG, as these constituted relevant data with respect to the transfer of knowledge. A reference was considered as linked to the recommendation when the reference or its content was explicitly mentioned.

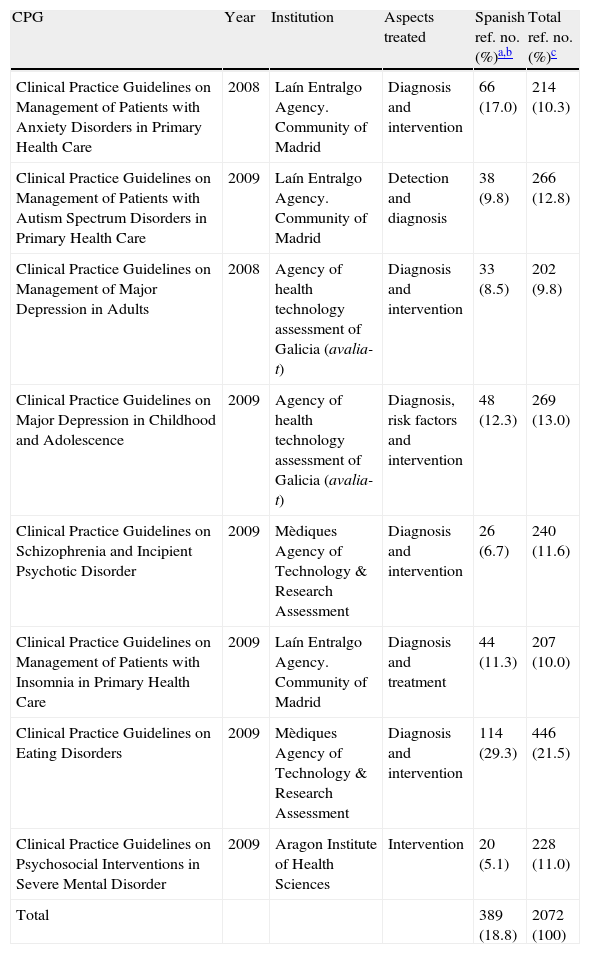

ResultsIn the first phase of the selection of the sample, 8 CPG were identified (these included subjects such as anxiety,7 autism,8 schizophrenia,9 depression,10,11 insomnia,12 eating disorders13 and severe mental disorder14). In these, 389 bibliographic references with at least 1 author affiliated with a Spanish institution were identified (Table 1).

CPG selected, characteristics and references identified.

| CPG | Year | Institution | Aspects treated | Spanish ref. no. (%)a,b | Total ref. no. (%)c |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Patients with Anxiety Disorders in Primary Health Care | 2008 | Laín Entralgo Agency. Community of Madrid | Diagnosis and intervention | 66 (17.0) | 214 (10.3) |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Primary Health Care | 2009 | Laín Entralgo Agency. Community of Madrid | Detection and diagnosis | 38 (9.8) | 266 (12.8) |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Major Depression in Adults | 2008 | Agency of health technology assessment of Galicia (avalia-t) | Diagnosis and intervention | 33 (8.5) | 202 (9.8) |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines on Major Depression in Childhood and Adolescence | 2009 | Agency of health technology assessment of Galicia (avalia-t) | Diagnosis, risk factors and intervention | 48 (12.3) | 269 (13.0) |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines on Schizophrenia and Incipient Psychotic Disorder | 2009 | Mèdiques Agency of Technology & Research Assessment | Diagnosis and intervention | 26 (6.7) | 240 (11.6) |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines on Management of Patients with Insomnia in Primary Health Care | 2009 | Laín Entralgo Agency. Community of Madrid | Diagnosis and treatment | 44 (11.3) | 207 (10.0) |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines on Eating Disorders | 2009 | Mèdiques Agency of Technology & Research Assessment | Diagnosis and intervention | 114 (29.3) | 446 (21.5) |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines on Psychosocial Interventions in Severe Mental Disorder | 2009 | Aragon Institute of Health Sciences | Intervention | 20 (5.1) | 228 (11.0) |

| Total | 389 (18.8) | 2072 (100) |

CPG: clinical practice guidelines; Ref.: references.

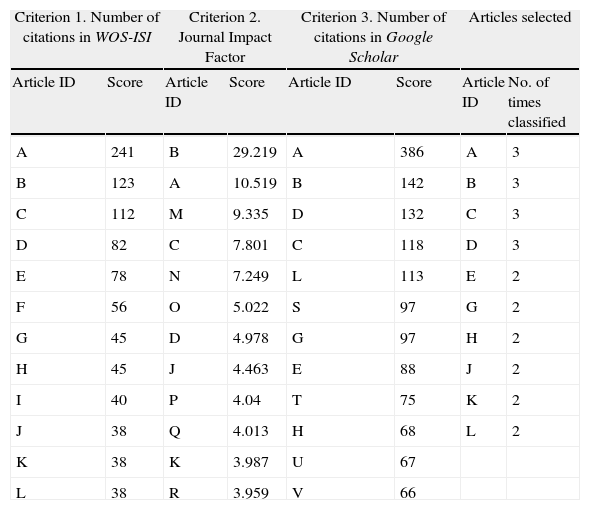

Among these references there were 130 original articles that were classified into 3 rankings according to the 3 criteria of “scientific quality” mentioned earlier. In the case of Criterion 1 (citations in WOS-ISI), there was more than 1 article with the same number of citations. Consequently, 12 articles were selected instead of 10 (Table 2).

Classification and selection of the original articles.

| Criterion 1. Number of citations in WOS-ISI | Criterion 2. Journal Impact Factor | Criterion 3. Number of citations in Google Scholar | Articles selected | ||||

| Article ID | Score | Article ID | Score | Article ID | Score | Article ID | No. of times classified |

| A | 241 | B | 29.219 | A | 386 | A | 3 |

| B | 123 | A | 10.519 | B | 142 | B | 3 |

| C | 112 | M | 9.335 | D | 132 | C | 3 |

| D | 82 | C | 7.801 | C | 118 | D | 3 |

| E | 78 | N | 7.249 | L | 113 | E | 2 |

| F | 56 | O | 5.022 | S | 97 | G | 2 |

| G | 45 | D | 4.978 | G | 97 | H | 2 |

| H | 45 | J | 4.463 | E | 88 | J | 2 |

| I | 40 | P | 4.04 | T | 75 | K | 2 |

| J | 38 | Q | 4.013 | H | 68 | L | 2 |

| K | 38 | K | 3.987 | U | 67 | ||

| L | 38 | R | 3.959 | V | 66 | ||

By combining the 3 classifications, a final sample of 10 articles was obtained. Four of these were included in the 3 criteria and 6 were included in 2 (Table 2).

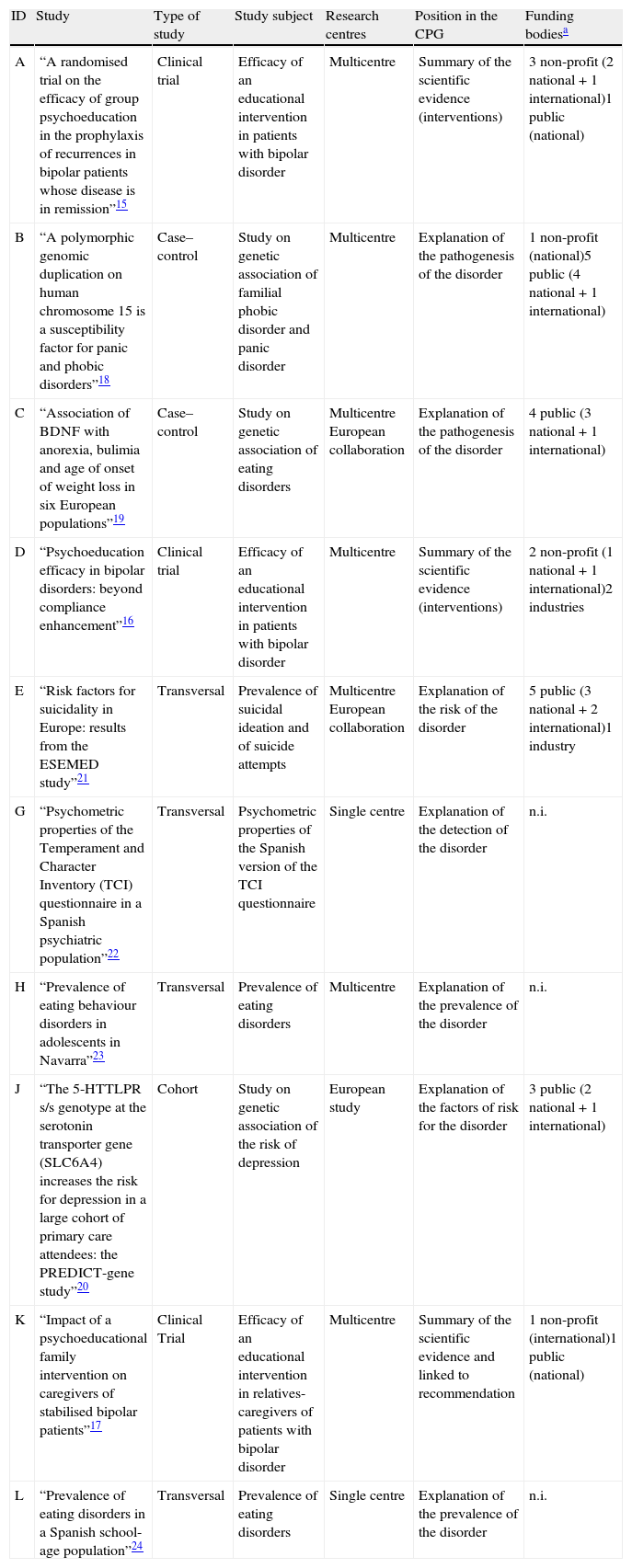

We now turn to the description of the content and the methodology of these 10 articles cited in the CPG that, in turn, fulfil the criteria of “quality” according to the methodology described (Table 3).

Characteristics of the original Spanish articles selected.

| ID | Study | Type of study | Study subject | Research centres | Position in the CPG | Funding bodiesa |

| A | “A randomised trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission”15 | Clinical trial | Efficacy of an educational intervention in patients with bipolar disorder | Multicentre | Summary of the scientific evidence (interventions) | 3 non-profit (2 national+1 international)1 public (national) |

| B | “A polymorphic genomic duplication on human chromosome 15 is a susceptibility factor for panic and phobic disorders”18 | Case–control | Study on genetic association of familial phobic disorder and panic disorder | Multicentre | Explanation of the pathogenesis of the disorder | 1 non-profit (national)5 public (4 national+1 international) |

| C | “Association of BDNF with anorexia, bulimia and age of onset of weight loss in six European populations”19 | Case–control | Study on genetic association of eating disorders | Multicentre European collaboration | Explanation of the pathogenesis of the disorder | 4 public (3 national+1 international) |

| D | “Psychoeducation efficacy in bipolar disorders: beyond compliance enhancement”16 | Clinical trial | Efficacy of an educational intervention in patients with bipolar disorder | Multicentre | Summary of the scientific evidence (interventions) | 2 non-profit (1 national+1 international)2 industries |

| E | “Risk factors for suicidality in Europe: results from the ESEMED study”21 | Transversal | Prevalence of suicidal ideation and of suicide attempts | Multicentre European collaboration | Explanation of the risk of the disorder | 5 public (3 national+2 international)1 industry |

| G | “Psychometric properties of the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) questionnaire in a Spanish psychiatric population”22 | Transversal | Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the TCI questionnaire | Single centre | Explanation of the detection of the disorder | n.i. |

| H | “Prevalence of eating behaviour disorders in adolescents in Navarra”23 | Transversal | Prevalence of eating disorders | Multicentre | Explanation of the prevalence of the disorder | n.i. |

| J | “The 5-HTTLPR s/s genotype at the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) increases the risk for depression in a large cohort of primary care attendees: the PREDICT-gene study”20 | Cohort | Study on genetic association of the risk of depression | European study | Explanation of the factors of risk for the disorder | 3 public (2 national+1 international) |

| K | “Impact of a psychoeducational family intervention on caregivers of stabilised bipolar patients”17 | Clinical Trial | Efficacy of an educational intervention in relatives-caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder | Multicentre | Summary of the scientific evidence and linked to recommendation | 1 non-profit (international)1 public (national) |

| L | “Prevalence of eating disorders in a Spanish school-age population”24 | Transversal | Prevalence of eating disorders | Single centre | Explanation of the prevalence of the disorder | n.i. |

BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CPG: clinical practice guidelines; n.i.: not indicated; TCI: Temperament and Character Inventory.

Articles A (“A randomised trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission”),15 D (“Psychoeducation efficacy in bipolar disorders: beyond compliance enhancement”)16 and K (“Impact of a psychoeducational family intervention on caregivers of stabilised bipolar patients”)17 refer to 3 single-blind clinical trials. They assessed the efficacy of educational group therapy in bipolar disorder in both patients (Articles A and D) and their relatives-caregivers (Article K). The authors assigned the patients randomly to receive conventional drug treatment and unstructured group sessions in the control group, while the active treatment group received specific educational sessions. Follow-up lasted up to 2 years and the efficacy of the intervention was tested in terms of lower relapse rate, delay in the appearance of relapse and lower hospitalisation rate. In the trial carried out with relatives-caregivers, an assessment was made, likewise using random assignment, of the efficacy of 12 weekly educational sessions on acquiring training about bipolar disorder and the skills and capabilities of coping. This trial was also positive, demonstrating by the use of a specific measurement tool that, while the objective load of the relatives remained unchanged, the relatives’ subjective perception of the load did indeed decrease. In addition, to a highly important degree, the relatives reduced the assignment of patient responsibility to the perturbation generated by the disorder. The 3 clinical trials were carried out by the same research group and, as can be deduced from the text of the articles, were based on a population seen at the same time, possibly contemporaneously.

Article B (“A polymorphic genomic duplication on human chromosome 15 is a susceptibility factor for panic and phobic disorders”)18 was a case–control study that analysed the familial panic and phobic disorder and ligamentous hyperlaxity in 7 families 178 patients affected, and an independent sample of 70 patients with non-familial panic disorder. The results reached in the genetic analysis of these patients were compared with those obtained in 189 controls. Cytogenetics and FISH analysis made it possible to identify an interstitial duplication of chromosome 15q24-26 (DUP 25), which was shown to be associated with family cases of phobia, panic disorder and ligamentous hyperlaxity, as well as to non-familial cases of panic disorder. The authors proposed that DUP 25 could be an important genetic factor of familial susceptibility to panic and phobic disorders with ligamentous hyperlaxity, as well as to non-familial panic disorder. The authors also suggested that there might be a non-Mendelian inheritance mechanism with a different level of penetration. This article generated controversy after its publication, when the findings were not replicated in later studies.

Article C (“Association of BDNF with anorexia, bulimia and age of onset of weight loss in six European populations”)19 was a case–control study that analysed the association of 2 variants of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene and its single nucleotide polymorphism with appetite disorders (anorexia and bulimia nervosa). The sample consisted of 1142 patients from 5 European countries plus 510 controls. The study was based on data from previous studies that pointed to the same direction. Likewise, there was prior literature that indicated a possible direct relationship between BDNF and the pathogenesis of eating disorders. The results of the study showed a strong association of the 2 variants of the gene studied with all of the clinical subtypes of this disorder. The authors defended that these were the first findings of variants of this gene that predisposed for these disorders. The study also illustrated the need for the use of very large samples in order to demonstrate, in association studies, a genetic effect in a complex phenotype.

Article J (“The 5-HTTLPR s/s genotype at the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) increases the risk for depression in a large cohort of primary care attendees: the PREDICT-gene study”)20 was a cohort study. It presented the analysis of an aspect of the genetic basis for the risk of depression. The authors studied genetic samples and administered a validated questionnaire (Composite International Diagnostic Interview [CIDI]) for depression and another for anxiety, taking blood and saliva samples for genetic analysis, to consecutive individuals that went to primary health care centres for consults (n=737). In all the samples the polymorphism 5-HTTLPR was genotyped in the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4), considered to be an indicator of risk of depression. After rejections and losses, the univariate and multivariate analyses of 737 participants (80% of the total) displayed an association with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.50 between the genotype and the episodes of depression; this association was even stronger (OR: 1.79) for severe depression. The association between the polymorphism studied and depression had already been described, but the authors felt that the results of previous studies were contradictory. For that reason, they performed their study (PREDICT-gene study) in the context of a wider European study (Project PREDICT) whose objective was studying depression in primary health care.

Despite referring to different mental disorders (phobic and panic disorders, eating disorders and risk of depression), the last 3 articles described share a common methodological link: they study the association between genetic determinants and the mentioned mental disorders. In this group of studies there is also an overlap of authors in 2 of them. Interestingly, 1 of the 3 articles is an international collaboration within the European environment. As has already been emphasised, in this case clinical trials were not involved; the article handles analytical observational designs (cohorts and case–controls).

Article E (“Risk factors for suicidality in Europe: findings from the ESEMED study”)21 was a transversal descriptive study. Like the last of the studies mentioned, it was of European focus. However, in this case it was not a study on genetic association, but a wide international study in which the goal was to evaluate prevalence in suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in a large random sample (8796 individuals) from the general population of 6 European countries, including Spain. The CIDI questionnaire was used as the measurement tool, detecting with it prevalence of 7.8% for suicidal ideation and 1.3% for suicide attempts. Spain was identified as having one of the lowest prevalence figures. Factors of risk determined included suffering a major mental disease or being unemployed.

Article G (“Psychometric properties of the Temperament and Character Inventory [TCI] questionnaire in a Spanish psychiatric population”)22 likewise describes a transversal descriptive study that assessed the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the TCI questionnaire. This instrument assesses 7 basic dimensions of personality and in the study it was administered to 416 consecutive psychiatric patients with affective disorders, anxiety, depression or drug dependence. Based on the analysis performed, the authors concluded that the psychometric properties of the instrument were appropriate for the sample studied.

Finally, Articles H23 and L24 (“Prevalencia de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en las adolescentes navarras” [Prevalence of eating disorders in adolescents in Navarra] and “Prevalence of eating disorders in a Spanish school-age population”) had various characteristics in common: they were prevalence studies referring to eating disorders and focused exclusively on Spain, in 2 different communities. They also shared the instruments of measurement. However, they differed in the methods of participant selection (random in both cases) and in participant ages. In spite of these differences, the results were quite similar with respect to bulimia (0.8% and 1.24%) but differed somewhat with respect to anorexia nervosa (0.3% and 0.69%), with the results of the first study being just outside the interval of confidence of those of the second study. An important result of one of the studies was the increase in prevalence of eating disorders, comparing it with a study performed 10 years earlier that found prevalence figures ranging from 1.55% to 4.69%, respectively.

DiscussionThe analysis of the content of these 10 articles makes it possible to identify some of the characteristics that, independently of the quality of the methodology and execution, can have been associated to the relevance demonstrated by their impact and by being chosen to be incorporated into documents that reflect the most relevant scientific evidence and aim to influence decision-making. This represents a further sample that research can produce improvements in clinical practice and, consequently, in the mental health of our society and its citizens.25

SubjectsThe articles analysed referred to a wide variety of prevalent mental diseases with the notable exception of schizophrenia. It does not therefore appear that the selection of a specific disorder as the object of research represents in and of itself a greater probability of diffusion.

DesignWith respect to the design of the studies, the dominance of complex designs (experimental and analytical)15–20 over the simply descriptive21–24 is notable in this sub-sample of articles having elevated bibliometric impact. However, the overall sample of articles cited in the guidelines featured a predominance of simpler descriptive designs.5

Research centresEight of the 10 articles describe multicentre studies. Three of them correspond to international European collaborations,19–21 where not only the research team was international, but the population of patients as well. This is, undoubtedly, another feature that helps to characterise a group of studies having “scientific quality”. The fact that they are collaborative studies and that they had large samples has been taken, among others, as one of the factors explaining the elevated number of citations.26

FundingIt is notable that the majority of the articles selected have been financed primarily by public institutions, whether local or European in nature. This fact contrasts with the data from other countries, where the private sector (both industry and non-profit organisations) contributes in a higher percentage in research than the governmental bodies.4 In addition, it is surprising that articles funded by local bodies can have such a notable impact. Nevertheless, Lewison and Dawson27 found that there was a relationship between research that had the most funding organisms available, in addition to other factors, and the fact of achieving higher impact; for example, in the number of citations.

Perceived scientific and practical relevancePutting a value to the scientific and practical relevance of the articles is complex and very dependent on subjective criteria. At any rate, in all the articles, the authors themselves are very explicit in emphasising the elements that they feel indicate this relevance. In the 3 clinical trials carried out by the same research group on the efficacy of regulated educational interventions in patients with bipolar disorder15,19 and in their relatives-caregivers,17 the scientific importance and the potential of practical application of the studies would basically derive, in the opinion of the authors, from being the first controlled and random clinical trials on this type of intervention. This is true as much in the case of the patients as of the caregivers, and also from being findings of real interest in the management of the illness and its environment.

The relevance of the 3 studies on genetic association also stems from involving novel findings. Even acknowledging that they refer to areas in which some prior information exists, part of that data comes from studies by the same authors. The relevance of these works for the scientific community is made clearly evident by the fact that one of them (Article B)18 aroused considerable controversy when its findings were not replicated in later studies,28–30 while another (Article J)20 represents a contribution to a contentious and highly debated topic on which there are even several meta-analyses.20,31 Both characteristics help to explain why these articles have been cited repeatedly. As is obvious, the authors do not propose any immediate practical application of these study results. However, it is a given that greater understanding of the pathogenic basis of the illnesses studied will facilitate advances in their treatment in the long range.

The relevance of the European study on suicidal ideation and suicide attempts21 stems, in the authors’ opinion, from a greater knowledge of their factors of risk, which could in turn facilitate corresponding policies in public health and even in the clinical attitudes of the health professionals involved. The 2 studies on the prevalence of eating disorders in different populations of Spanish adolescents represent a contribution to local knowledge on these disorders about which, at least posteriorly, information has been plentiful. However, due to characteristics of rigour of the studies, they probably represent observations that can be generalised to a wider environment than that of the execution of the studies. Finally, the practical relevance of the study on validating the TCI instrument22 stems from the fact that it is the first validation of a Spanish version of this questionnaire. In the opinion of the authors, this will facilitate its use in the Hispanic environment.

Position of the references or influence of their content in the clinical practice guidelinesAn interesting aspect related to the relevance of these articles having “scientific quality” with respect to decision-making is to consider the use to which they have been put in the CPG; that is to say, which position they hold within the guidelines. The Spanish CPG are not an exception removed from the Anglo-Saxon world with respect to the scant contribution of local research considering 2 factors: the volume of studies on which they are based (19% of studies were Spanish according to a study that analysed the Spanish references in the same sample of CPG5) and the proportion in which they contributed to specific recommendations. In the sample under consideration here, the 3 clinical trials related to bipolar disorder are mentioned in the summary of the scientific evidence on which decision-making is based, but only 1 is expressly linked to specific recommendations. The rest of the studies, as is logical considering their subjects and objectives, are mentioned in the synthesis of the literature that summarises the pathogenesis, prevalence or clinical characteristics of the mental diseases and is not linked to recommendations.

Limitations and strengths of the studyThis work does not propose a statistical or comparative assessment of any type. As in every study where content is analysed qualitatively, the aim is to suggest characteristics or processes of interest, rather than establish numerical frequencies and quantitative comparisons. Another thing to consider is the question of up to what point the sample of articles selected for this analysis is appropriate for it. Their selection criteria are certainly conventional. However, as was explained in “Methods” section, these criteria seem, because of their rigour, to guarantee the identification of articles that have truly demonstrated a maximum level of bibliometric impact in the subject group chosen. Consequently, it is realistic to say that the characteristics of methodology and of other types identified in this analysis identify the Spanish research studies on mental health with probability of reaching notoriety in the scientific community and in the area of preparation of CPG. One last aspect that should be emphasised is the relevance in the analysis of the citations of the articles compared with the factor of impact of the journal with all its weaknesses. This indicator provides information about the use that is given to the articles and, therefore, supplies a more scientific perspective to the analysis.

Another study limitation is the fact that all the Spanish CPG existing on mental disorders were not included in the analysis. Those in the GuíaSalud register were specifically selected because the CPG published in this catalogue require established methodological criteria for their inclusion. For this reason, we have not taken into consideration other CPG registers that are widely accepted in some fields, such as Fisterra in primary health care.32

This study makes it possible to identify a series of predominant characteristics that can reasonably be associated with an elevated number of bibliographic citations achieved. These characteristics include: sophisticated designs (experimental or analytical) and the multicentre character of the studies, especially with international collaboration. Among the studies that have achieved notoriety belong some basic science ones that examine or analyse genetic associations in the pathogenesis of mental illnesses and others on the efficacy of educational interventions. The content of the latter makes them the ones that have had the most influence in the CPG, being cited in the summary of the scientific evidence or being linked to recommendations. The confirmation or rebuttal of prior findings in controversial topics may have contributed equally to the wide citation of the studies. Some of these tend to be concentrated in a few centres of “excellence”. However, the wide variety of subjects addressed suggests a certain dispersion in the area studied. Certainly, this study does not attempt to characterise Spanish mental health research globally; however, it does describe a few characteristics that appear in studies with great probabilities of diffusion and it could be useful for the design of future lines of research or publication.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or animals have been performed for this investigation.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Permanyer-Miralda G, Adam P, Guillamón I, Solans-Domènech M, Pons JMV. Características de artículos españoles de «calidad científica» citados en las guías de práctica clínica en salud mental. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2013;6:150–159.