The introduction of anti-psychotic medication and the de-institutionalization have placed on the hands of their relatives the responsibility for their informal care. Many times, this role carries a high level of burden for all family members. There exist a few studies that approach this subject matter in groups of ethnic minority. The aim of this research was to describe the levels of burden in Aymaras caregivers (aborigines who are located on the highlands of Northen Chile) from Schizophrenia patients.

Material and methodsThe sample corresponds to 45 caregivers of patients with schizophrenia that receive treatment at the Mental Health Services in the city of Arica, Chile.

ResultZarit Burden Scale classifies all Aymara relatives in the category of “Intense Burden”, unlike not Aymara relatives, which is classified as “Low Burden”. Significant differences are observed in the subscale of incompetence where the Aymara Cargivers perceive not to feel able of taking care of the patient with the available resources.

ConclusionsIt is concluded that belonging to this ethnic minority would increase the psychopathological risk that caregivers of psychiatric patients experience.

La introducción de los fármacos anti-psicóticos y la desinstitucionalización han colocado en los familiares de los pacientes que padecen esquizofrenia la responsabilidad del cuidado informal. Ello conlleva, muchas veces, a una alta sobrecarga para sus miembros. Existen escasos estudios que aborden esta temática en población indígena. El objetivo de esta investigación fue el evaluar los niveles de sobrecarga en familiares de pacientes con esquizofrenia pertenecientes a la etnia aymara (indígenas que se ubican en el altiplano al Norte de Chile).

Material y métodosLa muestra estudiada corresponde a 45 cuidadores de pacientes con esquizofrenia usuarios del Servicio de Salud Mental de la ciudad de Arica, Chile.

ResultadosLa escala de Sobrecarga de Zarit clasifica a todos los familiares de etnia Aymara en la categoría de «sobrecarga intensa» a diferencia de los familiares no Aymaras quedaron clasificados de «sobrecarga leve». Se observa además diferencias significativas en la subescala de incompetencia donde los cuidadores aymaras perciben no sentirse capaz de cuidar al paciente con los recursos disponibles.

ConclusionesSe concluye que la pertenencia a esta minoría étnica incrementaría el riesgo psicopatológico que los cuidadores de pacientes psiquiátricos experimentan.

The incidence of schizophrenia in Chile is approximately 12 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. In the regions of Arica and Parinacota, along with the Metropolitan area, there is a greater prevalence of this alteration.1

Most families have assumed “informal care” of these patients, with the considerable burden this implies.2,3 Due to this added responsibility, there has been an increasing awareness regarding the difficulties experienced by families that have to manage and adjust to a complex mental disorder within their households.4

These difficulties are associated to experiencing feelings of anger, anxiety, guilt, fear, frustration and sadness, as well as a reduction in quality of life and a significant impact on the health and function of relatives.5,6

Burden has been defined primarily in terms of the impact caused by the disorder on the quality of life of those who assume the role of caregivers.2,7 It is considered as a multi-cause construct generated by a combination of the clinical characteristics and duration of the disorder,8 the personality features of the family, household responsibilities, forms of social support available and, finally, the economic cost of the disease.9–11 Some variables (such as employment outside the home) influence the perception of family burden and seem to have a significant positive effect on the overall health of family members, reducing the perception of burden.2From this perspective, it becomes essential that healthcare services adopt measures in agreement with the community model of mental healthcare to offer support for family members who often lack information about the symptoms of the disorder, as well as the necessary skills and adequate social support to carry out a healthcare role.12,13 In this sense, psychosocial interventions play a significant role in the overall treatment of patients and their relatives.2,14–16

Moreover, those families with members suffering mental illness and belonging to an ethnic minority experience a double stigma, due to the pathology and to their lower social status. In addition to their caring role, family members experience social and cultural stigma and other factors related to the immigration process, all of which increases their burden.15

Most families belonging to ethnic minorities have less social support and less information about community resources, and must face language barriers and a low socioeconomic status.

In this context, Aymara cosmology separates the world into 3 dimensions: social relationships, relationship with the “gods” and relationship with nature. These 3 dimensions are closely intertwined and fully integrated into the landscape and nature in general. It could be said that their way of understanding the universe revolves around “cyclical” natural processes from which they have developed a ritual calendar.

Therefore, human behaviour is guided by this fundamentally “cultivator” conviction, based on relationships. For these reasons, the Aymara do not see themselves as masters of nature, but rather as an intrinsic part of it, and regard it as essential for the maintenance of their desired harmony (ritual, educational, economic). The narrative principle of the Aymara (which considers “a good life” as a harmonious path) historically stems from a dynamic and cohesive concept of culture, involving the whole of the population regardless of their personal identity options.17

However, it is clear that one cannot speak simply of “the” Aymara tradition as a homogeneous and isolated concept. Aymara tradition always exists in relation to society and changes constantly.18

Considering this dynamic and interrelating conception of Aymara tradition, we can say that their actions will be related to the need to preserve and maintain balance and harmony. If we attempted to define Aymara ethics, these would be based on a different community experience from the hegemonic Occidental ethics, which are based on individualism and personal achievement. Thus, urban environments often break with the characteristic concept of balance and harmony of the Andean worldview. However, these same urban contexts may lead to new patterns incorporating other practices and interface systems.18

This breakdown in a way of life can often lead to psychological maladjustment. For this reason, and considering that cultural and ethnic characteristics play an important role in the perception of burden, the objective of this study was to assess the levels of burden in relatives of patients with schizophrenia belonging to the Aymara ethnic group.

Material and methodsDesignThis work corresponds to a case-control study.

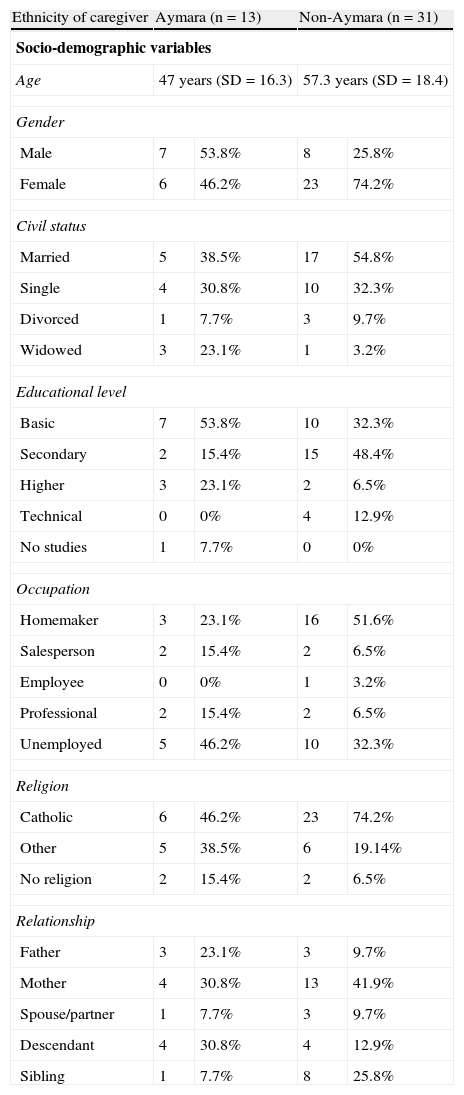

SubjectsThe population studied comprised 45 caregivers. This was divided into 2 groups (Aymara and non-Aymara), whose sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Social and demographic characteristics of Aymara and non-Aymara caregivers.

| Ethnicity of caregiver | Aymara (n=13) | Non-Aymara (n=31) | ||

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||

| Age | 47 years (SD=16.3) | 57.3 years (SD=18.4) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 7 | 53.8% | 8 | 25.8% |

| Female | 6 | 46.2% | 23 | 74.2% |

| Civil status | ||||

| Married | 5 | 38.5% | 17 | 54.8% |

| Single | 4 | 30.8% | 10 | 32.3% |

| Divorced | 1 | 7.7% | 3 | 9.7% |

| Widowed | 3 | 23.1% | 1 | 3.2% |

| Educational level | ||||

| Basic | 7 | 53.8% | 10 | 32.3% |

| Secondary | 2 | 15.4% | 15 | 48.4% |

| Higher | 3 | 23.1% | 2 | 6.5% |

| Technical | 0 | 0% | 4 | 12.9% |

| No studies | 1 | 7.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Occupation | ||||

| Homemaker | 3 | 23.1% | 16 | 51.6% |

| Salesperson | 2 | 15.4% | 2 | 6.5% |

| Employee | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3.2% |

| Professional | 2 | 15.4% | 2 | 6.5% |

| Unemployed | 5 | 46.2% | 10 | 32.3% |

| Religion | ||||

| Catholic | 6 | 46.2% | 23 | 74.2% |

| Other | 5 | 38.5% | 6 | 19.14% |

| No religion | 2 | 15.4% | 2 | 6.5% |

| Relationship | ||||

| Father | 3 | 23.1% | 3 | 9.7% |

| Mother | 4 | 30.8% | 13 | 41.9% |

| Spouse/partner | 1 | 7.7% | 3 | 9.7% |

| Descendant | 4 | 30.8% | 4 | 12.9% |

| Sibling | 1 | 7.7% | 8 | 25.8% |

SD: standard deviation.

Aymara caregivers were defined as those who identified themselves as belonging to that ethnic group. Since 1 participant did not specify his ethnic group, the final sample consisted of 31 caregivers who did not consider themselves Aymara and 13 caregivers who did.

InstrumentsZarit Burden Scale19This instrument was adapted and validated for Spanish by Martin et al. in 1996. Likewise, it was validated in Chile by Breinbauer et al. in 2009.20,21

The scale provides information about the intensity of caregiver burden. It consists of 22 items, with a minimum score of 22 and a maximum of 110. The items include aspects of emotional impact, social and family support and problem management strategies. The cut-off points for the scale would be “no burden”=22–46; “slight burden”=47–55 and “intense burden”=56–110. In addition, the scale has 3 dimensions, which are: burden (negative evaluation by caregivers of their role), rejection (feelings of ambivalence, discomfort or rejection) and incompetence (perception of not being able to care for patients with the resources available).

ProcedureThe research team at the University of Tarapaca was authorised by the Mental Health Service of Arica to review the records of patients with schizophrenia. The study was approved by the Bioethics Advisory Committee of the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development of the Government of Chile.

Prior to the implementation of the instruments through an interview, subjects were informed about the objectives of the research, the voluntary character of their participation, confidentiality of data and inclusion criteria. If they agreed to participate, they were asked to sign an informed consent form. The inclusion criteria allowed the primary caregiver of each patient (that is, the person who devoted most time to patient care) to participate in the study.

We then proceeded to collect clinical and socio-demographic data and applied the burden scale. The application took place at the homes of caregivers.

ResultsFirstly, we assessed whether the 2 caregiver groups studied (Aymara and non-Aymara) showed significant differences in their demographic characteristics. We found no significant differences in age [t(42)=−1.74; P=.09], gender [χ2(1)=2.08; P=.15], civil status [χ2(3)=4.51; P=.21], occupation [χ2(4)=4.24; P=.37] and religion [χ2(2)=3.23; P=.19]. However, we did find significant differences regarding educational level [χ2(4)=9.98; P=.04]. Among caregivers with basic studies, 41.2% were Aymara and 58.8% were non-Aymara. Among those with secondary education, 11.8% were Aymara and 88.2% were non-Aymara. Among caregivers with higher education, 60% were Aymara and 40% were non-Aymara. All caregivers who had technical level were non-Aymara and the only uneducated caregiver was Aymara. However, it should be noted that, due to the small sample size, the chi-square analysis performed with the categorical demographic variables did not follow the assumption of minimum expected frequency per cell. Therefore, the results obtained should be interpreted with caution.

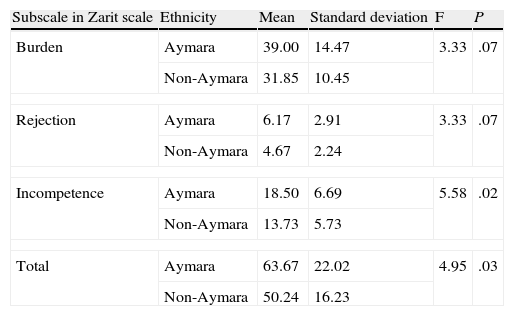

Table 2 shows the results in relation to the burden experienced by caregivers. Significant differences between Aymara and non-Aymara families could be observed in the total score and the incompetence subscale.

Results related to burden experienced by Aymara and non-Aymara caregivers.

| Subscale in Zarit scale | Ethnicity | Mean | Standard deviation | F | P |

| Burden | Aymara | 39.00 | 14.47 | 3.33 | .07 |

| Non-Aymara | 31.85 | 10.45 | |||

| Rejection | Aymara | 6.17 | 2.91 | 3.33 | .07 |

| Non-Aymara | 4.67 | 2.24 | |||

| Incompetence | Aymara | 18.50 | 6.69 | 5.58 | .02 |

| Non-Aymara | 13.73 | 5.73 | |||

| Total | Aymara | 63.67 | 22.02 | 4.95 | .03 |

| Non-Aymara | 50.24 | 16.23 | |||

Moreover, the total burden score placed Aymara relatives in the category of “intense burden.” In contrast, non-Aymara relatives fell into the classification of “slight burden”.

DiscussionThe results show that Aymara families present a greater level of burden stemming from their caregiver role. In addition, belonging to an ethnic minority increases the psychopathological risk of these caregivers.

These findings are closely related to the difficulty in obtaining community support, since many of these families are unaware of how to access different health services and, hence, intervention programs. The latter fact is consistent with previous studies, which indicated that the lack of resources for the protection and support of patients and family could be a variable influencing their perceived burden.13,15

Moreover, the low educational level of Aymara caregivers could be related to their high level of burden. Juvang et al. found a significant negative correlation between these 2 variables. It has even been suggested that a higher educational level may act as a “cushion” against burden.22,23

Another demographic factor related to the level of burden is the fact that a significant number of Aymara caregivers were single. The lack of this support has also been reported previously.24 Not having a partner reduces the chance of sharing the responsibility of caring for another person.

It is also possible that the perception of discrimination by the community is present in these relatives, thus increasing their burden, as observed in previous studies.15,25

Finally, the process of cultural adaptation that these families experience when they move from the foothills to the city, understood as a “westernised” culture, may also increase feelings of incompetence, defined as the perception of not being able to care for the patient with the resources available. Moreover, it has also been noted that the economic burden plays an important role in increasing the perception of incompetence, as is also the case with Latino, Chinese and African minorities in the USA.2,26

Within the limitations of the study are, firstly, the small sample size and the imbalance between the number of participants belonging to the Aymara (n=13) and non-Aymara (n=31) groups. The small number of participants, especially in the Aymara group, did not allow us to establish that the 2 groups compared in this study had similar demographic characteristics, despite the fact that statistical analyses seemed to indicate so. Therefore, the results obtained in this study should be interpreted with caution. A second limitation is having evaluated only the primary caregivers. For this reason, the results obtained cannot be extrapolated to the whole family. Moreover, because data collection took place at home, it was difficult to control environmental variables that could interfere with or bias the information. Another limitation is related to having assessed the burden in a specific period. Future research should consider making longitudinal assessments of this construct.

Mental health services should focus on achieving greater and better integration of these families within the intervention programs considering their specific identity and worldview and adapting their approach to both patients and their relatives.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

FinancingThis study was funded by the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development FONDECYT. Research Initiation Project 11075102.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Convenio Desempeño Universidad de Tarapacá-MINEDUC.

Please cite this article as: Caqueo-Urízar A, et al. Sobrecarga en cuidadores aymaras de pacientes con esquizofrenia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2012;5:191–6.