To identify barriers to complete recovery in patients suffering from major depressive disorder.

MethodsA total of 461 psychiatrists participated in a cross-sectional, non-randomised, qualitative and multi-centre study based on a survey. The study questionnaire included 42 items related to management, prevalence, patient profile, impact of residual symptoms, barriers to full recovery, and strategies to increase complete recovery.

ResultsComplete recovery was defined by 86% of participants as complete remission of symptoms plus functional recovery. A total of 83.4% of participants considered that sick leave usually lasted more than 4 months. Seventy-five percent stated that residual symptoms were the main reason for prolongation of sick leave, and 62% that between 26% and 50% of patients complained of residual symptoms. Poor compliance with treatment was the most important barrier to complete recovery, followed by a lack of patient cooperation, late beginning of treatment, partial response to antidepressants, and low doses of antidepressant medication. In the case of partial response, 71.8% of participants chose to increase the dose of current treatment, and in the case of lack of response, 72.7% would switch to another antidepressant, and 22.8% would use the combination of two antidepressants, in which case 85.2% would choose agents with complementary mechanisms of action. Forty-nine percent of participants would recommend standard cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy for patients without complete response.

ConclusionsSome 50% of patients did not achieve complete remission, frequently related to persistence of residual symptoms. Achievement of complete recovery should be an essential objective.

El objetivo de este estudio fue identificar las barreras para lograr una recuperación completa en pacientes con depresión mayor.

MétodosUn total de 461 psiquiatras participaron en un estudio cualitativo, no randomizado, transversal y multicéntrico basado en una encuesta. El cuestionario incluía 42 ítems relacionados con el tratamiento, prevalencia, perfil del paciente, impacto de los síntomas residuales, barreras y estrategias para aumentar la recuperación completa.

ResultadosUn 86% de participantes definieron recuperación completa como la remisión completa de síntomas más recuperación funcional. Un 83,4% consideraron que las bajas laborales se suelen prolongar más de 4 meses. Un 75% que los síntomas residuales eran el principal motivo de esta prolongación de las bajas, y un 62% que un 26-50% de pacientes tenían síntomas residuales. La falta de adherencia al tratamiento fue la barrera más importante para la recuperación completa, seguida de falta de colaboración del paciente, inicio tardío del tratamiento, respuesta parcial y bajas dosis de antidepresivos. En caso de respuesta parcial, el 71,8% de los participantes aumentaría la dosis del tratamiento actual, y en caso de falta de respuesta, el 72,7% cambiaría a otro antidepresivo. Un 22,8% usaría la combinación de dos antidepresivos, en cuyo caso el 85,2% elegiría fármacos con mecanismos de acción complementarios. Un 49% recomendaría la psicoterapia cognitivo-conductual en pacientes sin respuesta completa.

ConclusionesEn un 50% de los pacientes no se logra la recuperación completa, con frecuencia por la presencia de síntomas residuales. Lograr la recuperación completa debe ser un objetivo imprescindible.

Major depressive disorder is a common and treatable psychiatric disease. However, it is associated with major functional impairment which in many other chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and arthritis,1 entails a high burden on health systems and high costs to society.2 In a recent study conducted in U.S.A., based on a series of interviews with 36,309 adults who participated in a national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related diseases in 2012–2013, life-long prevalence of major depressive disorder, coded DSM-5, was 20.6% and the prevalence in the last 12 months was 10.4%.3 It has been estimated that around 10% of adult patients who attend primary healthcare facilities present with significant clinically depressive symptoms,4,5 which increases to 30–50% in patients attended by the mental healthcare services.6–8

Furthermore, approximately 50% of patients with depressive disorder respond to initial antidepressant treatment but only 12–18% may improve to such an extent that they are classified as having completely recovered, free from residual symptoms and functional alteration.9,10 Often, complete recovery of a major depressive disorder is a long process during which the residual symptoms may persist for months. The patients with residual symptoms have a considerably higher risk of relapse, compared with those without residual symptoms.11 Also, the presence of residual symptoms is the most precise factor to predict the risk of relapse, regardless of whether the patient has been treated with pharmacological or psychotherapeutic therapy.12 Moreover, the more therapeutic steps required, the higher the rates of relapse to be expected during follow-up.13 Patients with residual symptoms are more likely to experience a chronic disease course, bad quality of life, reduced probability of recovery over time and an increase in psychosocial and socioeconomic impact.14,15 As the number of relapses increases, there is a tendency for depressive episodes to increase in frequency and become more treatment-resistant.16–18

Apart from the physical and emotional residual symptoms, cognitive deficits may also persist in patients who appear to have reached remission. Cognitive dysfunction, even in periods of symptom remission, can explain psychological and persistent functional impairments, difficulties in treatment compliance and an added complexity in disorder management to achieve improvement in results in patients with major depression.19 As a result it has been increasingly acknowledged that symptomatic remission is an insufficient goal in the treatment of major depressive disorder and that the return to premorbid psychosocial functioning must be considered the target objective.20 Recognition of obstacles which stand in the way of complete recovery is a necessary step in evaluating and prioritising the therapeutic objectives in patients with major depressive disorder. The aim of this study was to identify, within the framework of the psychiatric consultation, the main barriers considered by psychiatrists which, in their opinion, impede patients with major depression from achieving complete recovery as the problem escalates.

MethodsStudy designA non randomised, transversal qualitative study based on a survey was conducted (Estudio REcuperación COmpleta en depresión: un objetivo impRescinDible [RECORD]) (in English: Complete recovery from depression: an essential aim) within the framework of psychiatric units of the Spanish mental health services. The principal aim was to identify the main barriers which in the psychiatrists’ opinion impeded patients with major depression from achieving complete recovery and which magnified the problem. Secondary objectives consisted in establishing to what extent the psychiatrists interviewed considered: (a) that residual symptoms are present, (b) what the characteristics were of the patient profile with major depression who did not achieve complete recovery and (c) how to assess the impact on the functioning of patients with major depression who did not achieve complete recovery. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid, Spain.

Participants and proceduresFor this study a scientific committee was established, formed by three psychiatrists with long-standing experience in clinical psychiatry. They were all renowned authors of relevant and professional research publications in diagnosis and treatment of patients with psychiatric diseases, particularly with major depressive disorder. The members of the scientific committee were responsible for creating the questionnaire. Moreover, they coordinated and supervised the functioning and progress of the study, including data analysis results.

The final consensual questionnaire contained 42 items and was divided into six sections: section 1 (depression management) contained 10 items with questions on treatment objectives, pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions, adverse events and factors relating to complete recovery; section 2 (prevalence) contained 6 items; section 3 (patient profile) contained 6 items relating to symptoms and comorbidities; section 4 (impact) contained 7 items relating to the impact of residual symptoms; section 5 (barriers)contained 7 items referring to the factors which prevented achieving complete recovery and section 6 (strategies) contained 6 items related to therapeutic strategies to increase the rates of complete recovery. The questionnaire is described in the supplementary Appendix B material, available on internet. Data on the researcher were also collected, regarding socio-demographic traits, years of practice, type of centre, participation in research projects and associations to which they belong.

The participating study candidates were specialists in psychiatry who treated patients diagnosed with major depression and who worked in public and private mental health services throughout Spain. Fieldwork was conducted from 31st October to 30th November 2017. Participants were recruited though a diptych invitation to clinical psychiatry specialists registered in the Medynet database, the first Internet node exclusively dedicated to the health sector in Spain which currently includes data from approximately 190,000 users. A non randomised and stratified selection was used (the strata represent the number of psychiatrists in each autonomous community), non proportional to the universe of Spanish psychiatrists. Study participation was anonymous and voluntary. The study questionnaire was stored on an Internet platform which participants accessed through a web link included in the invitation diptych. Those psychiatrists who agreed to participate in the study were given the URL of the platform and the user password.

Statistical analysisTo determine sample size, probabilistic calculation based on binomial distribution adapted to FarmaIndustria recommendations for this type of study was used (www.codigofarmaindustria.org/servlet/sarfi/docs/PRODF117805.pdf), so that with an error margin of 5%, a confidence level of 95% and 50% heterogeneity, a sample size of 450 participants was obtained. Descriptive analysis of data included the description of frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables and the mean and standard deviation (SD) for the quantitative variables. Data were analysed with the SAS (Statistical Analysis Systems, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.) statistical programme version 9.1.3 for Windows.

ResultsA total of 461 psychiatrists, 249 men and 212 women participated in the study, with a mean age (SD) of 48.7 (9.8) years. The mean years of experience were 20.5 (9.5) years. 96.3% of participants were Spanish. 26% had participated in a training programme on major depression in the last 12 months and 13% were participating or had participated in research projects on major depression. Moreover, 54.9% of those interviewed were members of a medical society, most frequently the Spanish Society of Psychiatry (24.7% of cases). No questionnaires were excluded for being incomplete.

Depression managementOver 75% of the participants were quite concerned about all the problems mentioned in reference to depression management, with the most common being partial response without remission and persistence of residual symptoms (Appendix B: supplementary material, Table 1). 86% of respondents understood complete recover from depression as the total remission of symptoms and also functional recovery, and 50.5% always noted complete recovery as the final treatment objective. However, 48.8% indicated that some patients presented with a series of characteristics which meant that, right from the beginning, complete recovery could not be expected. “returning to normal functioning at work, at home or at school”, “retrieving hope and future projects” and “enjoying my normal activities” were the items of the survey selected by 76.4%, 39.7% and 38.8% of the participants, respectively, as indicators of complete recovery. Regarding assessment of the response to treatment, only 16.3% used scales, with the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory and the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale being the ones most commonly used. 40% of participants stated that between 26% and 50% of their patients with depression came to their surgeries with antidepressant drug treatment and 70%, stated that below 25% of their patients with depression received appropriate psychotherapy. The side effects of treatment were systematically assessed by 72% of the participants in over 75% of patients, mainly through systematic specific questions. However, 90% of participants stated that it was sometimes difficult to distinguish the side effects of treatment from the residual symptoms.

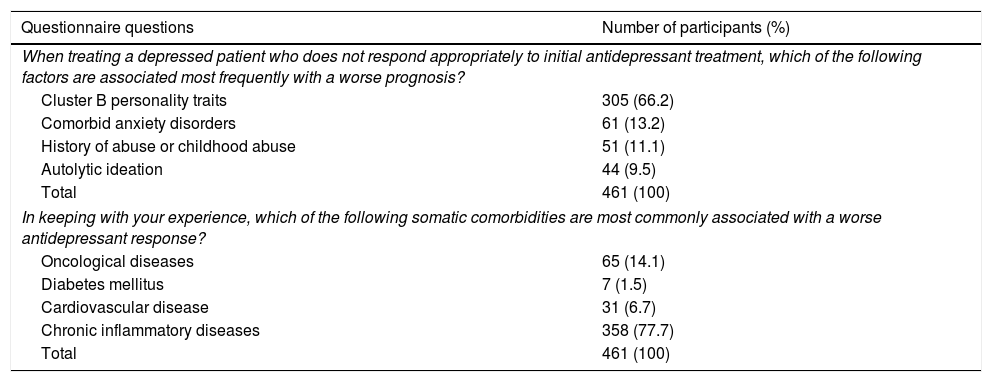

Factors associated with a worse prognosis and somatic comorbidities associated with a worse response to antidepressants.

| Questionnaire questions | Number of participants (%) |

|---|---|

| When treating a depressed patient who does not respond appropriately to initial antidepressant treatment, which of the following factors are associated most frequently with a worse prognosis? | |

| Cluster B personality traits | 305 (66.2) |

| Comorbid anxiety disorders | 61 (13.2) |

| History of abuse or childhood abuse | 51 (11.1) |

| Autolytic ideation | 44 (9.5) |

| Total | 461 (100) |

| In keeping with your experience, which of the following somatic comorbidities are most commonly associated with a worse antidepressant response? | |

| Oncological diseases | 65 (14.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (1.5) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 31 (6.7) |

| Chronic inflammatory diseases | 358 (77.7) |

| Total | 461 (100) |

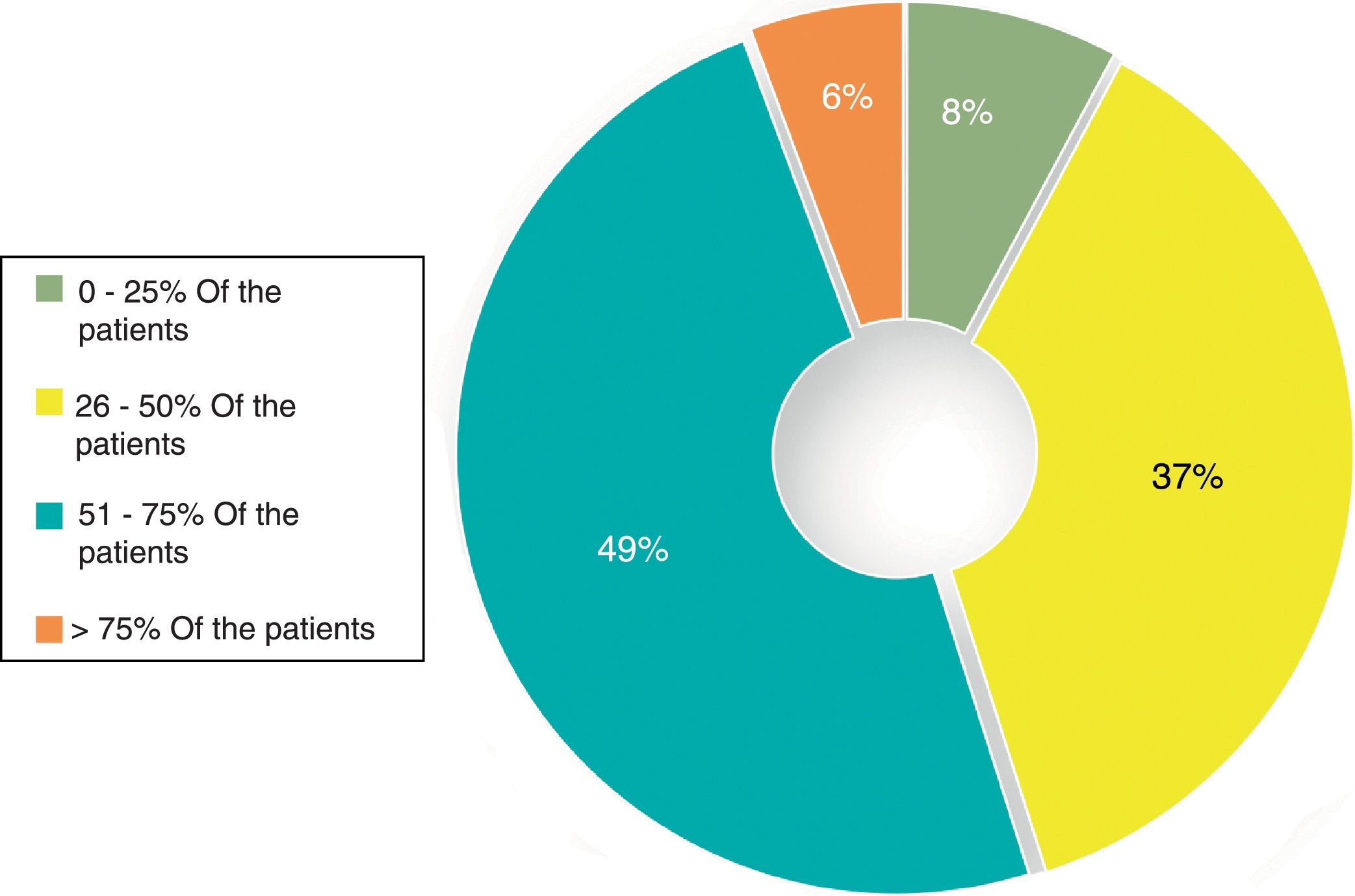

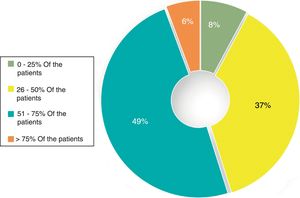

Fifty per cent of participants stated that 26–50% of the patients they had seen during the previous week presented with depression. Also, 62% of participants considered that the residual symptoms were present in 26–50% of cases. The most frequently mentioned residual symptoms were difficulties in concentration, asthenia/fatigue and anhedonia. Only 7.8% of participants mentioned sadness as a residual symptom. According to 60% of participants, between 21% and 40% of their patients with depression evolved towards chronicity. Furthermore, 45% of participants considered that under 50% of their patients achieved full recovery. Fig. 1 includes the opinion of the psychiatrists regarding the approximate percentages of patients who achieved full recovery after terminating antidepressant treatment.

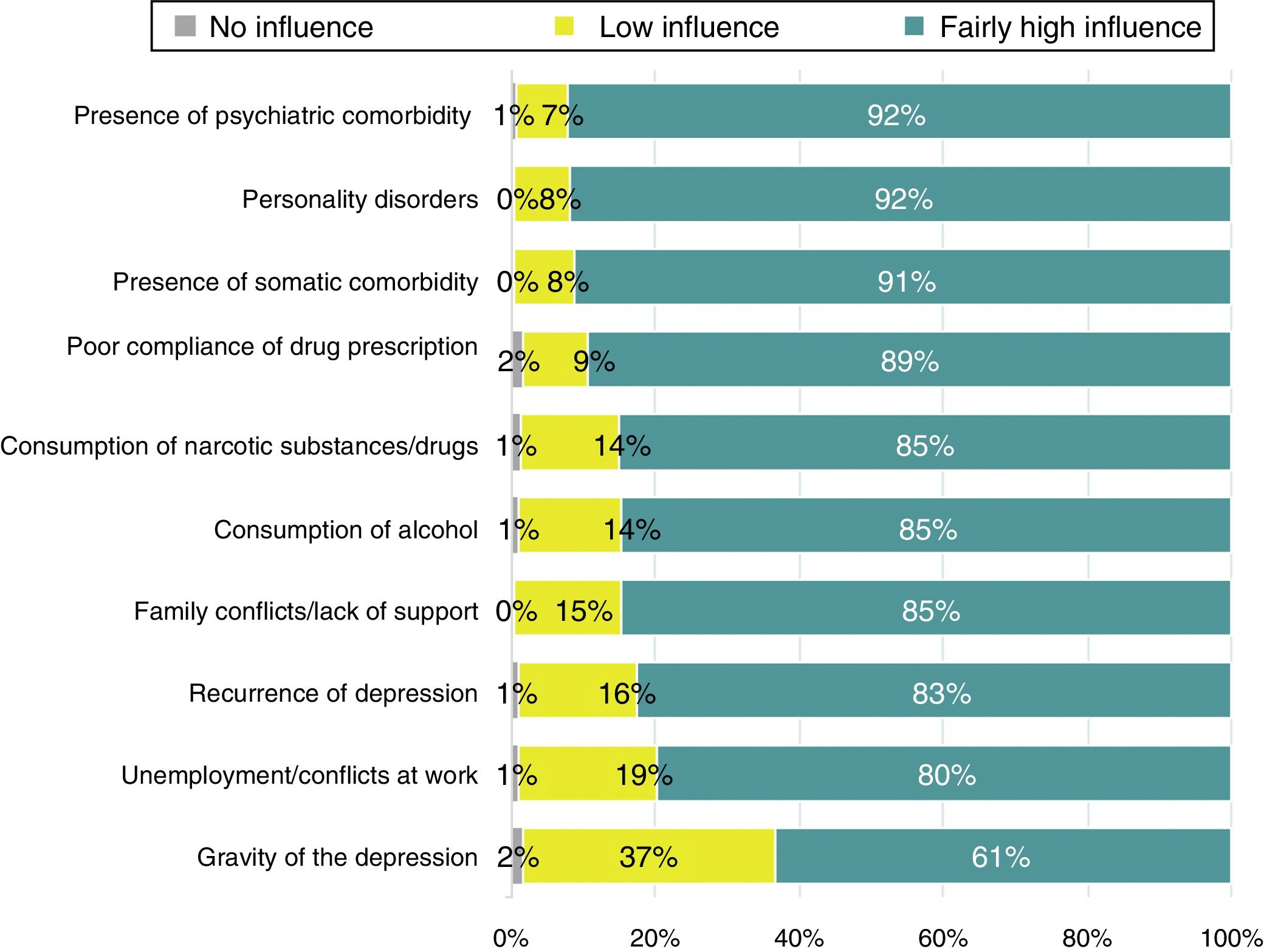

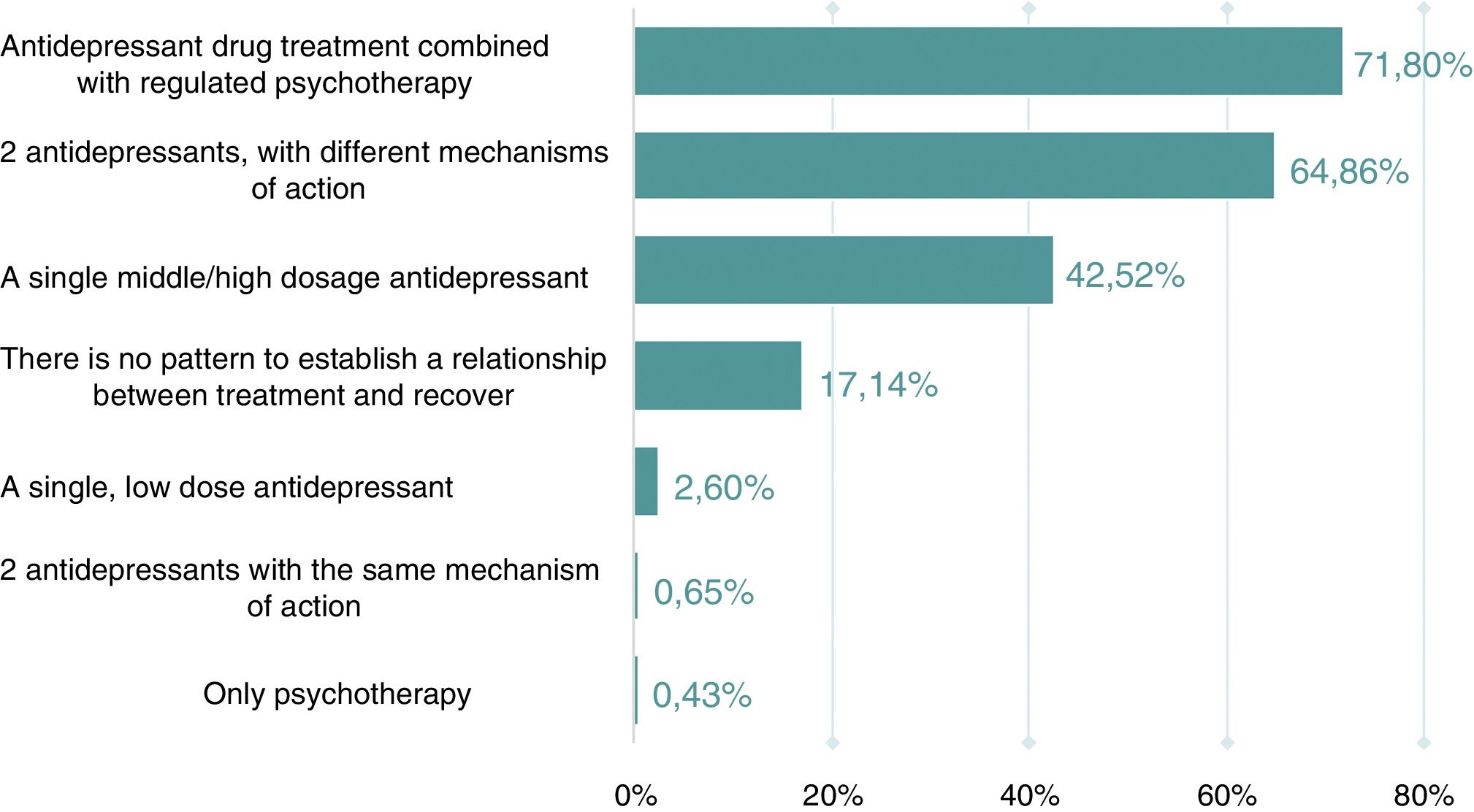

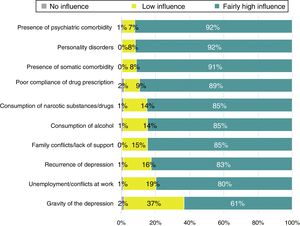

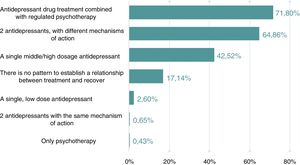

Patient profileMost participants considered that all the factors mentioned in the questionnaire were fairly influential in non full recovery, and especially psychiatric and somatic comorbidity and personality disorders (Fig. 2). Moreover, 66.2% of participants indicated that cluster B personality traits are the factors frequently associated with a worse prognosis and 78%, that chronic inflammatory diseases were the most common pathology associated with a worse response to antidepressant medication. The factors most frequently associated with a worse prognosis and somatic comorbidities related with poor response are contained in Table 1. Ninety one per cent of participants totally agreed or quite agreed that anxiety and insomnia are the most common symptoms in patients who present with residual symptoms. According to 72% of psychiatrists, the majority of patients who achieve full recovery are usually treated with antidepressant drugs and regulated psychotherapy or with two antidepressants with different mechanisms of action. The response obtained regarding therapeutic strategies in accordance with the treatment received by the patients who achieved full recovery are shown in Fig. 3.

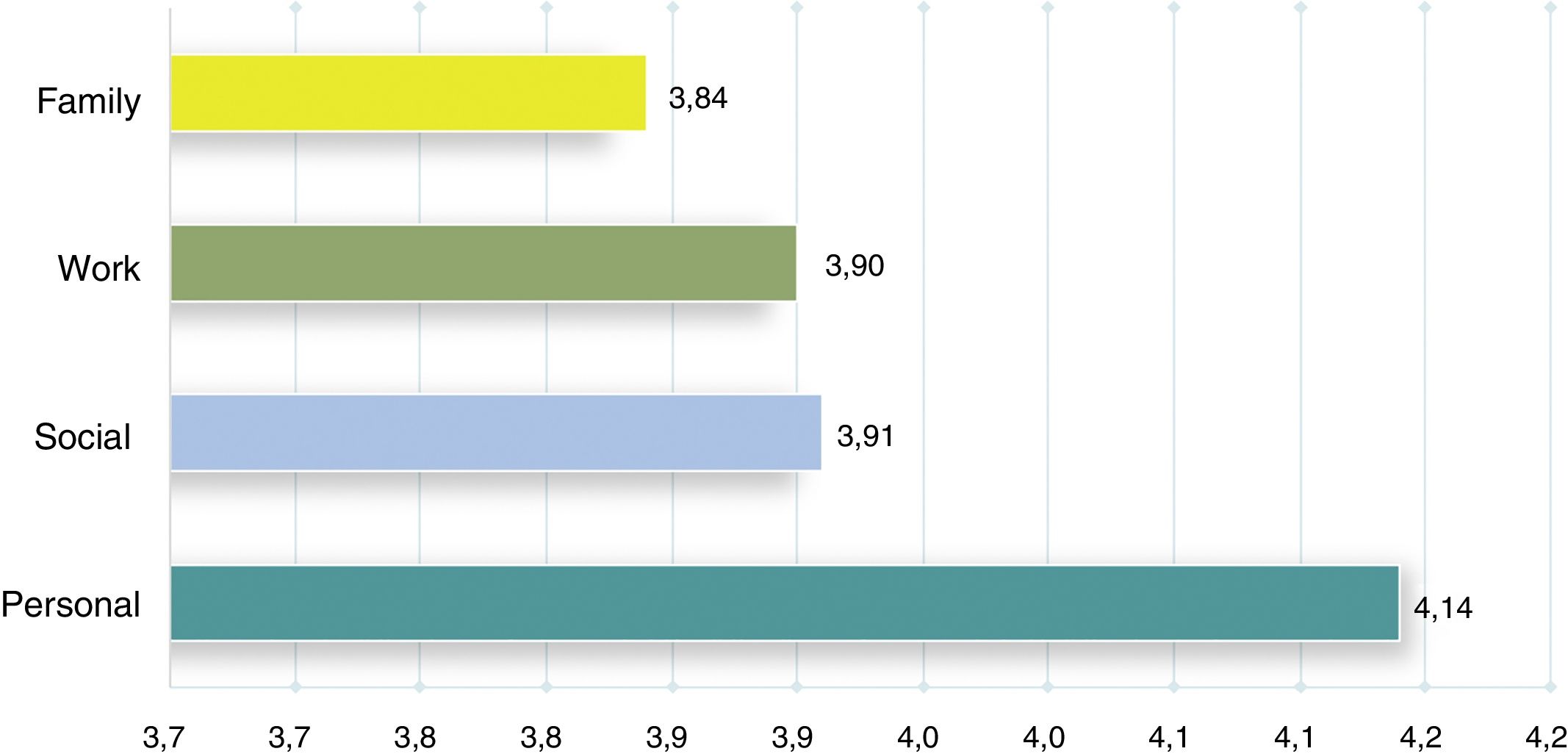

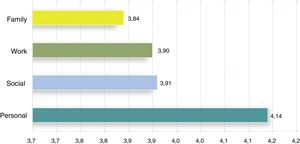

According to the opinion of 82% of the participants, the personal dimension was the most commonly affected by the residual symptoms, although those symptoms also affected the working, social and family environments of the patients. When the respondents gave a score to the intensity of the impact of the residual symptoms, the personal area obtained a mean of 4.1 (SD. 8), followed by social, working and family environment (Fig. 4).

Furthermore, 50.5% of the psychiatrists considered that 51–75% of patients with residual symptoms present with social dysfunction and/or relationship problems and 45.8% that their performance at work was affected for 51–75% of patients. Regarding the duration of sick leave for depression, 2.4% of participants referred to 1 or 2 months, 13.2% to 2–3 months, 45.8% to 4–6 months and 38.6% to over 6 months (supplementary material, Fig. 1). In total, 84.4% of participants were of the opinion that sick leave for depression usually lasted over 4 months and 75% that the persistence of residual symptoms was the most important factor to foster the prolongation of the sick leave for over 4–6 months. The factors which according to the participants’ criteria favoured the prolongation of the sick leave are shown in Fig. 2 of supplementary material.

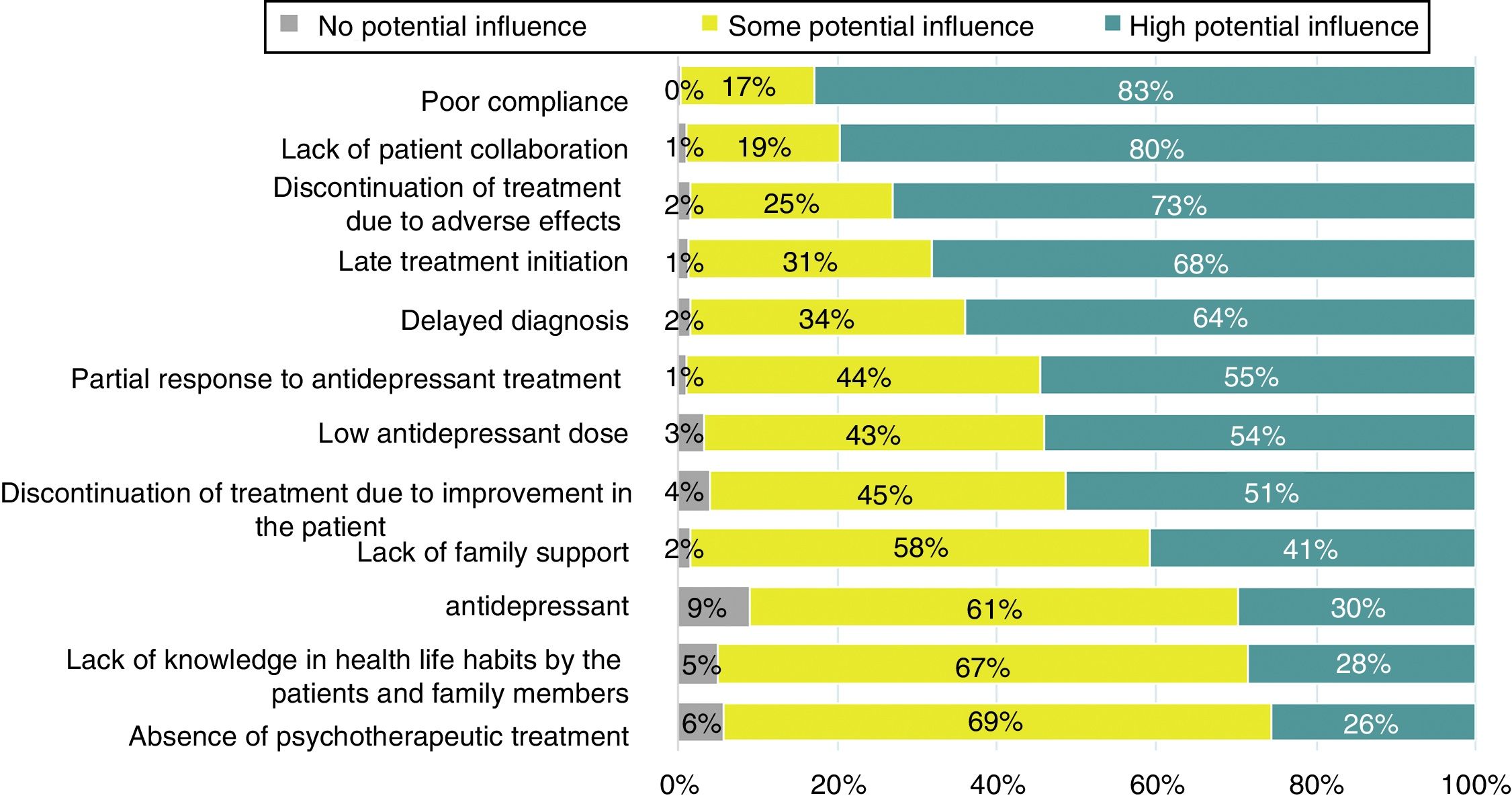

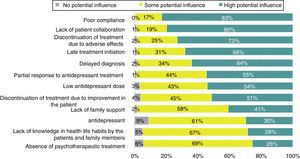

Barriers to full recoveryThe barriers to full recovery mentioned by the participants are shown in Fig. 5. Eighty two point nine per cent of participants stated that poor adherence to antidepressant treatment was the major barrier in achieving full recovery, followed by lack of patient cooperation, late treatment initiation, partial response to the antidepressants and low doses of antidepressant medication. According to 45% of participants, 50–74% of patients with depression had been accurately diagnosed but 46% considered that only 25–49% of patients had received correct treatment. In the opinion of 49% of psychiatrists, treatment was inappropriate because the patients should have been treated with higher doses. Resistance to drug treatment was mentioned by 61% of participants in 25–50% of patients. Forty seven point seven per cent of participants would recommend psychotherapy in over 75% of the patients with resistance to drug treatment. Regarding the risk of chronicity, the duration of the current depressive episode, treatment compliance and the number of therapy attempts were the three factors most frequently selected by the psychiatrists surveyed.

Treatment strategies for increasing the rates of full recoveryThe information to which most importance was attached to decide on the treatment for a patient who had been treated to the correct dose and time but without sufficient therapeutic response, 55.3% of participants considered patient symptoms as the most relevant aspect. When there was a partial response, 71.8% of participants would choose to raise the dose of current treatment and in the case of total absence of response, 72.7% would change to another antidepressant and 22.8% would recommend the combination of two antidepressants, in which case 85.2% would choose drugs with complementary mechanisms of action. According to the respondents, cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy would be recommended on average in 49% of patients when no treatment response was obtained. If regulated psychotherapy were necessary, 84.6% of participants would choose to refer the patient to another professional. Sixty point nine per cent of respondents said that those who should apply regulated psychotherapy were psychiatrists or clinical psychologists.

DiscussionDepression is the main cause of disability and substantially contributes to the worldwide burden of global morbidity through disease. In terms of economic burden, one of the major components derives from the loss of productivity at work.20,21 Despite appropriate antidepressant treatment determining the improvement of depressive symptoms and the ability for full recovery of the patient, there is a general infra and insufficient use of antidepressant medication which is actually effective and has a good tolerability profile.22 In this study 40% of the psychiatrists who took the survey stated that 26–50% of their patients were initially treated with antidepressants but that this treatment was suitable in under 25% of cases. It has often been shown that antidepressant treatment in patients with depression symptoms is incorrect, even in people who have attempted suicide.23 However, inappropriate treatment is also related to failure to establish a precise diagnosis of major depressive disorder, particularly at a primary care level.24

One interesting result of the study was that 62% of participants consider that residual symptoms were present in between 26% and 50% of their patients. However, despite this high frequency, sadness as a characteristic residual symptoms was only mentioned by 7.8% of those surveyed. Insomnia, sadness and difficulties in concentration are clinical symptoms which are repeatedly described as common individual symptoms in patients with response, but without full remission to antidepressant treatment.25 Problems relating to concentration and sleep disorders were selected as the most common residual symptoms by 58.8% and 34.7% of participants, respectively. Between 34% and 47% of the participants also chose asthenia/fatigue and anhedonia as common residual symptoms. Furthermore, 75% of participants considered that the presence of residual symptoms was the most common cause of the prolongation of sick leaves for over 4 months. Sick leave for depression is established in the manual of optimum times for temporary disability leave by the National Institute of Social Security as approximately 2 months. Also, the link between sick leave and previous problems at work was a factor which, in the opinion of 72% of participants, led to the increase of the duration of sick leave. In other studies, a background of sick leaves was a predictive factor of repeated sick leave in patients with mental illnesses, including major depression.26

Forty five per cent of participants state that up to 50% of patients did not achieve full recovery at the end of antidepressant treatment. The barriers against full recovery were related to the treatment itself, to poor compliance with drug prescriptions and the patient environment, such as lack of family support or lack of awareness of healthy life habits. The late initiation of this, delayed diagnosis, partial response to antidepressant medication and low doses of antidepressants were the most common barrier to treatment. Aspects relating to compliance included lack of adherence to prescribed antidepressant treatment, discontinuation of treatment due to adverse effects or suspension of medication due to an improvement in the patient's condition. Participants stated that lack of treatment compliance was related to several causes, among them, the interruption of treatment due to the patient's perception that medication was not necessary, fears relating to the adverse effects of medication, and the late effect of antidepressant medication, lack of clear instructions on dosage by the clinician, lack of follow-up, the presence of comorbidities (e.g. substance abuse disorder) or low patient motivation.27 In a systematic review on the effectiveness of the interventions aimed at improving adherence to antidepressant medication, educational interventions for increasing compliance did not demonstrate a clear benefit, since the interventions based on collaborative care of the patient were put into practice at primary care level, and demonstrated significant increases in adherence during acute stages and of treatment continuation especially in patients with major depressive disorder who had been prescribed the right doses of antidepressant medication.28

However, almost half of the participants (49%) considered that the patients must have received higher doses of antidepressants. In this way, a very small percentage of participants believed that monitoring of plasmatic levels of antidepressants as a form of treatment optimisation should be carried out more frequently to improve efficacy and prevent adverse effects, particularly for individualising and identifying patients with inappropriate response to antidepressants.29 Sixty one per cent of participants considered that resistance to drug treatment was a barrier in achieving full recovery in 25–50% de los patients. The current criteria of depression which is treatment-resistant includes the lack of response to two or more appropriate treatments (in terms of dose and duration) with antidepressants of different classes.30 Treatment-resistance mechanisms have not clearly and effectively established different therapeutic strategies, including guidelines for increasing the dose or combined therapies, nor have they compared them in populations of homogenous subgroups of patients.31 In our study, approximately 50% of participants recommended the use of psychotherapy in patients with resistance to drug treatment. Different clinical trials demonstrated the efficacy of several psychotherapeutic modalities,32,33 but evidence was not homogeneous.34

Regarding chronicity, over a third of participants stated that drug treatment adherence, the duration of the current episode and the number of prior therapeutic attempts as the three factors with the greatest influence for the chronic course of the disease. In a systematic review of 25 relevant primary studies with a total of 5192 patients, the risk factors for the presence of a chronic depression were the initiation at an early age, the long duration of the current depressive episode and a family history of emotional disorders.35 Also, psychological comorbidity, a low level of social integration and negative social interaction and the gravity of the depressive symptoms were concomitant factors of depression chronicity.

Given the burden of the major depressive disorder and the fact that only approximately one third of patients respond to initial antidepressant treatment, the need to implement strategies to improve the suboptimum level of results is increasingly imperious. Equally, the definitive aim of treatment has progressed from a mere response to treatment to full recovery, particularly given the negative implications of the presence of untreated residual symptoms. The strategies referred to by participants, including an increase in antidepressant doses, a change in the type of drugs and combination of agents with complementary action mechanisms together with combined antidepressant and psychotherapy treatment has been widely recommended for improving and maintaining remission rates in patients with major depressive disorder.36 However, it is necessary to design multidimensional and effective strategies to create a working environment where depression may be diagnosed early and managed in an appropriate manner.37

The results of this study should be interpreted bearing in mind several limitations, and particularly that patient selection was not random or proportional, so that the number of patients selected from each stratum (autonomous community) was not directly proportional to the size of each stratum, i.e. to the total number of psychiatrists in each autonomous community involved in management of patients with major depressive disorder. As a result it was not possible to establish the exact representation of study participants. The questionnaire was redacted in Spanish (96% of participants were Spanish) and distributed throughout Spanish territory, which eliminated any confusion factor from language barriers and differences in healthcare related to the diversity of healthcare systems. Also, although in the survey there was a section under the headline “prevalence”, the estimations referring to this point are based on the perception of psychiatrists with respect to the frequency of patients with major depression attended in their surgeries for residual symptoms, an evolution towards chronicity and full recovery. The aim of the survey was to provide information on the barriers preventing full recovery in patients with major depressive disorder treated in psychiatry clinics, in regular practice. Despite the limitations inherent in information based on the opinion of the psychiatrists consulted, its availability is meaningful for designing effective strategies to the benefit of long-term improvement in the results obtained regarding these patients.

ConclusionsThis study based on a survey conducted with psychiatrists on the different relevant aspects regarding the symptoms, treatment and impact of major depression provides a cross-sectional view on the perception of a significant group of healthcare professionals on one of the most prevalent mental health pathologies with the greatest onus. One highlight is that respondents were of the opinion that below 50% of patients made full recovery. In many cases this was due to the persistence of residual symptoms, such as cognitive disorders where difficulty in concentration, apathy, fatigue and anhedonia had notably affected the patients’ quality of life. Poor treatment compliance, somatic comorbidity or other concomitant mental disorders, together with inappropriate treatment in resistance forms of depression are some of the causes associated with a worse prognosis frequently mentioned by the participants. Whenever there is a lack of complete response psychiatrists believe that the combination of antidepressants with regulated psychotherapy or combined drug treatment with two antidepressants with complementary mechanisms of action is the most effective strategy.

FinancingThe funds necessary for realisation of the study were provided by the promoter, Laboratorios Servier. The promoter did not participate in data collection or analysis or interpretation. The authors declare that they were responsible for the decision to publish the document and have contributed to its redaction equally.

Conflict of interestsJulio Bobes received research funding, and during the last five years has been the consultant, adviser or speaker for: AB-Biotics, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Angelini, Casen Recordati, D&A Pharma, Exeltis, Gilead, GSK, Ferrer, Indivior, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Mundipharma, Otsuka, Pfizer, Reckitt-Benckiser, Roche, Servier, Shire and Schwabe Farma Ibérica; He obtained financing for research from the Ministry of the Economy and Competitiveness – Biomedical Centre for Research in the Mental Health Network (CIBERSAM) and from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III–, Spanish Ministry of Social Health and Equality – National Plan on Drugs and from the European Union's 7th Framework Programme.

During the last five years Jerónimo Saiz has participated as a speaker or expert for Adamed, Lundbeck, Servier, Neurofarmagen, Schwabe and Janssen; he has received funding for research from Public Bodies (CIBERSAM; FIS; CAM; University of Alcalá), the Fundación Canis Majoris, Lundbeck, Janssen, Medtronic and Ferrer.

During the last five years Víctor Pérez has received research funding and has been a consultant, advisor or speaker for AB-Biotics, Exeltis, Ferrer, Indivior, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer and Servier. He obtained funding for research from the Ministry of the Economy and Competitiveness – Biomedical Centre for Research in the Mental Health Network (CIBERSAM) and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III–, Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality and from the H2020 of the European Union.

The authors would like to thank Servier for sponsoring the Project, the Saned, S.L. group for logistical support in study development and Doctor Marta Pulido, for her collaboration in redacting the document.

Please cite this article as: Bobes J, Saiz-Ruiz J, Pérez V y el Grupo de Estudio RECORD. Barreras para la recuperación completa en la depresión mayor: estudio transversal multicéntrico en la práctica clínica. Estudio RECORD. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2018.10.002